Interest Rate Increase “Could Well Become Appropriate Relatively Soon,” Dollar Revaluation with Increasing Yields, World Inflation Waves, United States Industrial Production, Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016

I World Inflation Waves

IA Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy

IB1 Theory

IB2 Policy

IB3 Evidence

IB4 Unwinding Strategy

IC United States Inflation

IC Long-term US Inflation

ID Current US Inflation

IE Theory and Reality of Economic History, Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation

II United States Industrial Production

II IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

V World Economic Slowdown. Table V-1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=29) to show GDP in dollars in 2015 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2015 to 2018. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has changed its forecast of the world economy to 3.2 percent in 2015 and 3.1 percent in 2016 but accelerating to 3.4 percent in 2017 and 3.6 percent in 2018. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $34.171 billion of world output of $73,599 billion, or 46.4 percent, but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 1.7 percent on average from 2015 to 2018, in contrast with 3.3 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would grow 14.0 percent in the four years from 2015 to 2017, the G7 as a whole would grow 6.9 percent. The difference in dollars of 2015 is high: growing by 14.0 percent would add around $10.3 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly, two times the output of the economy of Japan of $4,124 billion but growing by 6.9 percent would add $5.1 trillion of output to the world, or about the output of Japan in 2015. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2019 of $29,039 billion, or 39.5 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 18.8 percent or at the average yearly rate of 4.4 percent, contributing $5.5 trillion from 2015 to 2017 or the equivalent of somewhat more than one half the GDP of $11,182 billion of China in 2014. The final four countries in Table V-1 often referred as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output in 2015 adds to $16,354 billion, or 22.2 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 47.9 percent of the combined output of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table I-1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2015 | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | |

| World | 73,599 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| G7 | 34,171 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Canada | 1,551 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| France | 2,420 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| DE | 3,365 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 1,816 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Japan | 4,124 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| UK | 2,858 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| US | 18,037 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Euro Area | 11,601 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| DE | 3,365 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| France | 2,420 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Italy | 1,816 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| POT | 199 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Ireland | 283 | 26.3 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Greece | 195 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

| Spain | 1,200 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| EMDE | 29,039 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 |

| Brazil | 1,773 | -3.8 | -3.3 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Russia | 1,326 | -3.7 | -0.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| India | 2,073 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| China | 11,182 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); POT: Portugal

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx). Table V-2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2014 to 2018 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates for 2014 in Table I-2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high in 2014 for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 13.9 percent for Portugal (POT), 11.3 percent for Ireland, 26.5 percent for Greece, 24.4 percent for Spain and 12.6 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 6.4 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table I-2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2014 | % Labor Force 2015 | % Labor Force 2016 | % Labor Force 2017 | % Labor Force 2018 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Canada | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.9 |

| France | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.3 |

| DE | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Italy | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| Japan | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| UK | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.4 |

| US | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Euro Area | 11.7 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.3 |

| DE | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| France | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.3 |

| Italy | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| POT | 13.9 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 10.3 |

| Ireland | 11.3 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 7.2 |

| Greece | 26.5 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 21.5 | 20.7 |

| Spain | 24.4 | 22.1 | 19.4 | 18.0 | 17.0 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 6.8 | 8.5 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 11.1 |

| Russia | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.5 |

| India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| China | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

Table V-3 provides the latest available estimates of GDP for the regions and countries followed in this blog from IQ2012 to IIQ2016 available now for all countries. There are preliminary estimates for all countries for IIQ2016. Growth is weak throughout most of the world.

- Japan. The GDP of Japan increased 0.9 percent in IQ2012, 3.7 percent at SAAR (seasonally adjusted annual rate) and 3.5 percent relative to a year earlier but part of the jump could be the low level a year earlier because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan is experiencing difficulties with the overvalued yen because of worldwide capital flight originating in zero interest rates with risk aversion in an environment of softer growth of world trade. Japan’s GDP fell 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 at the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of minus 1.5 percent, which is much lower than 3.7 percent in IQ2012. Growth of 3.5 percent in IIQ2012 in Japan relative to IIQ2011 has effects of the low level of output because of Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan’s GDP contracted 0.5 percent in IIIQ2012 at the SAAR of minus 2.0 percent and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IVQ2012 at the SAAR of minus 0.1 percent and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan grew 1.0 percent in IQ2013 at the SAAR of 4.1 percent and increased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP increased 0.7 percent in IIQ2013 at the SAAR of 2.8 percent and increased 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP grew 0.4 percent in IIIQ2013 at the SAAR of 1.8 percent and increased 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2013, Japan’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent at the SAAR of minus 0.2 percent, increasing 2.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP increased 1.3 percent in IQ2014 at the SAAR of 5.2 percent and increased 2.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2014, Japan’s GDP fell 2.0 percent at the SAAR of minus 7.8 percent and fell 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP contracted 0.7 percent in IIIQ2014 at the SAAR of minus 2.8 percent and fell 1.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2014, Japan’s GDP grew 0.6 percent, at the SAAR of 2.3 percent, decreasing 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Japan increased 1.2 percent in IQ2015 at the SAAR of 5.0 percent and decreased 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP decreased 0.3 percent in IIQ2015 at the SAAR of minus 1.3 percent and increased 0.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Japan increased 0.4 percent in IIIQ2015 at the SAAR of 1.6 percent and increased 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP contracted 0.4 percent in IVQ2015 at the SAAR of minus 1.6 percent and grew 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2016, the GDP of Japan increased 0.5 percent at the SAAR of 2.1 percent and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP increased 0.2 percent in IIQ2016 at the SAAR of 0.7 percent and increased 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2016, the GDP of Japan increased 0.5 percent at the SAAR of 2.2 percent and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier.

- China. China’s GDP grew 1.9 percent in IQ2012, annualizing to 7.8 percent, and 8.1 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 2.2 percent in IIQ2012, which annualizes to 9.1 percent, and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 1.8 percent in IIIQ2012, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 8.1 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 7.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, China grew at 1.7 percent, which annualizes at 7.0 percent, and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.1 percent in IIIQ2013, which annualizes at 8.7 percent, and increased 7.9 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 1.6 percent in IVQ2013, which annualized to 6.6 percent, and 7.7 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.7 percent in IQ2014, which annualizes to 7.0 percent, and 7.4 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.8 percent in IIQ2014, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.8 percent in IIIQ2014, which is equivalent to 7.4 percent in a year, and 7.1 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.8 percent in IVQ2014, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 1.6 percent in IQ2015, which annualizes at 6.6 percent, and 7.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.9 percent in IIQ2015, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and increased 7.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2015, China’s GDP grew at 1.7 percent, which annualizes at 7.0 percent, and increased 6.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 1.6 percent in IVQ2015, which annualizes at 6.6 percent, and increased 6.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.2 percent in IQ2016, which annualizes at 4.9 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2016, the GDP of China increased 1.9 percent, which annualizes to 7.8 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China increased at 1.8 percent in IIIQ2016, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. There is decennial change in leadership in China (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/index.htm). Growth rates of GDP of China in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier have been declining from 2011 to 2016.

- Euro Area. GDP fell 0.2 percent in the euro area in IQ2012 and decreased 0.5 in IQ2012 relative to a year earlier. Euro area GDP contracted 0.3 percent IIQ2012 and fell 0.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.1 percent and declined 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.4 percent relative to the prior quarter and fell 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, the GDP of the euro area fell 0.3 percent and decreased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.4 percent in IIQ2013 and fell 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, euro area GDP increased 0.3 percent and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.2 percent in IVQ2013 and increased 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2014, the GDP of the euro area increased 0.3 percent and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.2 percent in IIQ2014 and increased 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The euro area’s GDP increased 0.4 percent in IIIQ2014 and increased 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.4 percent in IVQ2014 and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Euro area GDP increased 0.8 percent in IQ2015 and increased 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.4 percent in IIQ2015 and increased 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The euro area’s GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2015 and increased 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. Euro area GDP increased 0.4 percent in IVQ2015 and increased 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. Euro area’s GDP increased 0.5 percent in IQ2016 and increased 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2016 and increased 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2016, the GDP of the euro area increased 0.3 percent and increased 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier.

- Germany. The GDP of Germany increased 0.4 percent in IQ2012 and increased 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2012, Germany’s GDP increased 0.1 percent and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier but 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier when adjusted for calendar (CA) effects. In IIIQ2012, Germany’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP contracted 0.5 percent in IVQ2012 and decreased 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, Germany’s GDP decreased 0.2 percent and fell 1.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.9 percent and grew 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.4 percent in IIIQ2013 and grew 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.4 percent and increased 1.4 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.6 percent in IQ2014 and grew 2.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2014, Germany’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2014 and increased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.8 percent in IVQ2014 and increased 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.2 percent in IQ2015 and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.5 percent in IIQ2015 and grew 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.2 percent in IIIQ2015 and grew 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.4 percent in IVQ2015 and grew 2.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2016, the GDP of Germany increased 0.7 percent and grew 1.5 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.4 percent in IIQ2016 and increased 3.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2016, the GDP of Germany increased 0.2 percent and grew 1.5 percent relative to a year earlier.

- United States. Growth of US GDP in IQ2012 was 0.7 percent, at SAAR of 2.7 percent and higher by 2.8 percent relative to IQ2011. US GDP increased 0.5 percent in IIQ2012, 1.9 percent at SAAR and 2.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, US GDP grew 0.1 percent, 0.5 percent at SAAR and 2.4 percent relative to IIIQ2011. In IVQ2012, US GDP grew 0.0 percent, 0.1 percent at SAAR and 1.3 percent relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, US GDP grew at 2.8 percent SAAR, 0.7 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.3 percent relative to the same quarter in 2012. In IIQ2013, US GDP grew at 0.8 percent in SAAR, 0.2 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.0 percent relative to IIQ2012. US GDP grew at 3.1 percent in SAAR in IIIQ2013, 0.8 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.7 percent relative to the same quarter a year earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states_30.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). In IVQ2013, US GDP grew 1.0 percent at 4.0 percent SAAR and 2.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2014, US GDP decreased 0.3 percent, increased 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier and fell 1.2 percent at SAAR. In IIQ2014, US GDP increased 1.0 percent at 4.0 percent SAAR and increased 2.4 percent relative to a year earlier. US GDP increased 1.2 percent in IIIQ2014 at 5.0 percent SAAR and increased 2.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2014, US GDP increased 0.6 percent at SAAR of 2.3 percent and increased 2.5 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.5 percent in IQ2015 at SAAR of 2.0 percent and grew 3.3 percent relative to a year earlier. US GDP grew at SAAR 2.6 percent in IIQ2015, increasing 0.6 percent in the quarter and 3.0 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.5 percent in IIIQ2015 at SAAR of 2.0 percent and grew 2.2 percent in IIIQ2015 relative to a year earlier. US GDP grew at SAAR of 0.9 percent in IVQ2015, increasing 0.2 percent in the quarter and 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2016, US GDP grew 0.2 percent at SAAR of 0.8 percent and increased 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. US GDP grew at SAAR of 1.4 percent in IIQ2016, increasing 0.4 percent in the quarter and 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2016, US GDP grew 0.7 percent at SAAR of 2.9 percent and increased 1.5 percent relative to a year earlier

- United Kingdom. In IQ2012, UK GDP increased 0.4 percent and increased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2012, GDP fell 0.1 percent relative to IQ2012 and increased 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, GDP increased 1.1 percent and increased 1.8 percent relative to the same quarter a year earlier. In IVQ2012, GDP fell 0.2 percent and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Fiscal consolidation in an environment of weakening economic growth is much more challenging. GDP increased 1.5 percent in IQ2013 relative to a year earlier and 0.6 percent in IQ2013 relative to IVQ2012. In IIQ2013, GDP increased 0.5 percent and 2.1 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIIQ2013 and 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.5 percent in IVQ2013 and 2.4 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2014, GDP increased 0.8 percent and 2.6 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.9 percent in IIQ2014 and 3.1 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIIQ2013 and 3.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2014, GDP increased 0.8 percent and 3.5 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.3 percent in IQ2015 and increased 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.5 percent in IIQ2015 and increased 2.4 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2015 and increased 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.7 percent in IVQ2015 and increased 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.4 percent in IQ2016 and increased 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.7 percent in IIQ2016 and grew 2.1 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.5 percent in IIIQ2016 and increased 2.3 percent relative to a year earlier.

- Italy. Italy’s GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2016 and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2016, GDP changed 0.0 percent and increased 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.4 percent in IQ2016 and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.2 percent in IVQ2015 and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2015, GDP increased 0.1 percent and increased 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.2 percent in IIQ2015 and 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.3 percent in IQ2015 and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP changed 0.0 percent in IVQ2014 and increased 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP changed 0.0 percent in IIIQ2014 and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IIQ2014 and increased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy changed 0.0 percent in IQ2014 and increased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IVQ2013 and fell 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 and fell 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP changed 0.0 in IIQ2013 and fell 2.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP fell 1.0 percent in IQ2013 and declined 2.8 percent relative to IQ2012. GDP had been growing during six consecutive quarters but at very low rates from IQ2010 to IIQ2011. Italy’s GDP fell in seven consecutive quarters from IIIQ2011 to IQ2013 at increasingly higher rates of contraction from 0.5 percent in IIIQ2011 to 1.0 percent in IVQ2011, 1.0 percent in IQ2012, 0.7 percent in IIQ2012 and 0.5 percent in IIIQ2012. The pace of decline accelerated to minus 0.6 percent in IVQ2012 and minus 1.0 percent in IQ2013. GDP contracted cumulatively 5.2 percent in seven consecutive quarterly contractions from IIIQ2011 to IQ2013 at the annual equivalent rate of minus 3.0 percent. The yearly rate has fallen from 2.2 percent in IVQ2010 to minus 2.8 percent in IVQ2012, minus 2.8 percent in IQ2013, minus 2.1 percent in IIQ2013 and minus 1.3 percent in IIIQ2013. GDP fell 0.7 percent in IVQ2013 relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.3 percent in IQ2014 relative to a year earlier and increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2014 relative to a year earlier. GDP changed 0.0 percent in IIIQ2014 relative to a year earlier and increased 0.1 percent in IVQ2014 relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.4 percent in IQ2015 relative to a year earlier and increased 0.6 percent in IIQ2015 relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.6 percent in IIIQ2015 relative to a year earlier and increased 0.9 percent in IVQ2015 relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.9 percent in IQ2016 relative to a year earlier and increased 0.7 percent in IIQ2016 relative to a year earlier. GDP increased 0.9 percent in IIIQ2016 relative to a year earlier. Using seasonally and calendar adjusted chained volumes in the dataset of EUROSTAT (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat). the GDP of Italy in IIQ2016 of €390,734.3 million is lower by 8.0 percent relative to €424,823.8 million in IQ2008. The fiscal adjustment of Italy is significantly more difficult with the economy not growing especially on the prospects of increasing government revenue. The strategy is for reforms to improve productivity, facilitating future fiscal consolidation.

- France. France’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent in IQ2012 and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP decreased 0.2 percent in IIQ2012 and increased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, France’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IVQ2012 and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, France’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France increased 0.7 percent in IIQ2013 and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IIIQ2013 and increased 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France increased 0.3 percent in IVQ2013 and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2014, France’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent and increased 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2014, France’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2014 and increased 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France increased 0.2 percent in IVQ2014 and increased 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP increased 0.6 percent in IQ2015 and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2015, France’s GDP changed 0.0 percent and increased 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP increased 0.4 percent in IIIQ2015 and increased 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2015, the GDP of France increased 0.3 percent and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP increased 0.6 percent in IQ2016 and increased 1.4 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France decreased 0.1 percent in IIQ2016 and increased 1.3 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP increased 0.2 percent in IIIQ2016 and increased 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier.

Table V-3, Percentage Changes of GDP Quarter on Prior Quarter and on Same Quarter Year Earlier, ∆%

| IQ2012/IVQ2011 | IQ2012/IQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.7 SAAR: 2.7 | 2.8 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.7 | 3.5 |

| China | 1.9 | 8.1 |

| Euro Area | -0.2 | -0.5 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| France | -0.1 | 0.4 |

| Italy | -1.0 | -2.2 |

| United Kingdom | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| IIQ2012/IQ2012 | IIQ2012/IIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 1.9 | 2.5 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.4 | 3.5 |

| China | 2.2 | 7.6 |

| Euro Area | -0.3 | -0.8 |

| Germany | 0.1 | 0.4 0.9 CA |

| France | -0.2 | 0.3 |

| Italy | -0.7 | -3.2 |

| United Kingdom | -0.1 | 1.0 |

| IIIQ2012/ IIQ2012 | IIIQ2012/ IIIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.1 | 2.4 |

| Japan | QOQ: –0.5 | 0.2 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.5 |

| Euro Area | -0.1 | -1.0 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Italy | -0.5 | -3.2 |

| United Kingdom | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| IVQ2012/IIIQ2012 | IVQ2012/IVQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.0 | 1.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.0 SAAR: -0.1 | 0.0 |

| China | 1.9 | 8.1 |

| Euro Area | -0.4 | -1.1 |

| Germany | -0.5 | -0.1 |

| France | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Italy | -0.6 | -2.8 |

| United Kingdom | -0.2 | 1.3 |

| IQ2013/IVQ2012 | IQ2013/IQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 1.0 SAAR: 4.1 | 0.3 |

| China | 1.9 | 7.9 |

| Euro Area | -0.3 | -1.2 |

| Germany | -0.2 | -1.5 |

| France | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| Italy | -1.0 | -2.8 |

| UK | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| IIQ2013/IQ2013 | IIQ2013/IIQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.2 SAAR: 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.7 SAAR: 2.8 | 1.1 |

| China | 1.7 | 7.6 |

| Euro Area | 0.4 | -0.4 |

| Germany | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| France | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Italy | 0.0 | -2.1 |

| UK | 0.5 | 2.1 |

| IIIQ2013/IIQ2013 | III/Q2013/ IIIQ2012 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.8 | 1.7 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.4 SAAR: 1.8 | 2.0 |

| China | 2.1 | 7.9 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| France | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Italy | 0.3 | -1.3 |

| UK | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| IVQ2013/IIIQ2013 | IVQ2013/IVQ2012 | |

| USA | QOQ: 1.0 SAAR: 4.0 | 2.7 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.1 SAAR: -0.2 | 2.1 |

| China | 1.6 | 7.7 |

| Euro Area | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| France | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Italy | 0.0 | -0.7 |

| UK | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| IQ2014/IVQ2013 | IQ2014/IQ2013 | |

| USA | QOQ -0.3 SAAR -1.2 | 1.6 |

| Japan | QOQ: 1.3 SAAR: 5.2 | 2.7 |

| China | 1.7 | 7.4 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Germany | 0.6 | 2.6 |

| France | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| UK | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| IIQ2014/IQ2014 | IIQ2014/IIQ2013 | |

| USA | QOQ 1.0 SAAR 4.0 | 2.4 |

| Japan | QOQ: -2.0 SAAR: -7.8 | -0.3 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.5 |

| Euro Area | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Germany | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| UK | 0.9 | 3.1 |

| IIIQ2014/IIQ2014 | IIIQ2014/IIIQ2013 | |

| USA | QOQ: 1.2 SAAR: 5.0 | 2.9 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.7 SAAR: -2.8 | -1.5 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.1 |

| Euro Area | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Germany | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| France | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| UK | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| IVQ2014/IIIQ2014 | IVQ2014/IVQ2013 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.6 SAAR: 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.6 SAAR: 2.3 | -0.9 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.2 |

| Euro Area | 0.4 | 1.3 |

| Germany | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| UK | 0.8 | 3.5 |

| IQ2015/IVQ2014 | IQ2015/IQ2014 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 2.0 | 3.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 1.2 SAAR: 5.0 | -1.0 |

| China | 1.6 | 7.0 |

| Euro Area | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| France | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Italy | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| UK | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| IIQ2015/IQ2015 | IIQ2015/IIQ2014 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.6 SAAR: 2.6 | 3.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.3 SAAR: -1.3 | 0.8 |

| China | 1.9 | 7.0 |

| Euro Area | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Germany | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| France | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Italy | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| UK | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| IIIQ2015/IIQ2015 | IIIQ2015/IIIQ2014 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.4 SAAR: 1.6 | 1.9 |

| China | 1.7 | 6.9 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| France | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Italy | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| UK | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| IVQ2015/IIIQ2015 | IVQ2015/IVQ2014 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.2 SAAR: 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.4 SAAR: -1.6 | 0.7 |

| China | 1.6 | 6.8 |

| Euro Area | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| France | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Italy | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| UK | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| IQ2016/IVQ2015 | IQ2016/IQ2015 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.2 SAAR: 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 2.1 | 0.2 |

| China | 1.2 | 6.7 |

| Euro Area | 0.5 | 1.7 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| France | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| UK | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| IIQ2016/IQ2016 | IIQ2016/IIQ2015 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.4 SAAR: 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.2 SAAR: 0.7 | 0.6 |

| China | 1.9 | 6.7 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 3.1 |

| France | -0.1 | 1.3 |

| Italy | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| UK | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| IIIQ2016/IIQ2016 | IIIQ2016/IIIQ2015 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.7 SAAR: 2.9 | 1.5 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 2.2 | 0.9 |

| China | 1.8 | 6.7 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 1.5 |

| France | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Italy | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| UK | 0.5 | 2.3 |

QOQ: Quarter relative to prior quarter; SAAR: seasonally adjusted annual rate

Source: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

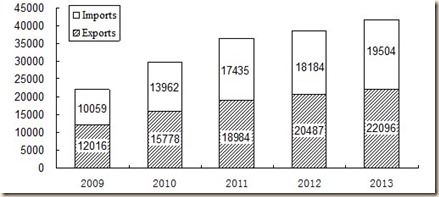

Table V-4 provides two types of data: growth of exports and imports in the latest available months and in the past 12 months; and contributions of net trade (exports less imports) to growth of real GDP.

- Japan. Japan provides the most worrisome data (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/valuation-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/dollar-revaluation-squeezing-corporate.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/imf-view-of-economy-and-finance-united.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/financial-and-international.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/05/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/05/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/financial-risks-slow-cyclical-united.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations_8763.html http://cmpass ocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/interest-rate-risks-duration-dumping.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/duration-dumping-steepening-yield-curve.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/06/paring-quantitative-easing-policy-and_4699.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/05/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states_24.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/contraction-of-united-states-real_25.html and for GDP http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what_13.html). In Aug 2016, Japan’s exports increased 9.6 percent in 12 months while imports decreased 17.3 percent. The second part of Table V-4 shows that net trade deducted 1.7 percentage points from Japan’s growth of GDP in IIQ2012, deducted 1.8 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2012 and deducted 0.5 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2012. Net trade added 0.3 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2012, 1.8 percentage points in IQ2013 and deducted 0.5 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.3 percentage points from GDP growth in Japan. Net trade ducted 1.9 percentage points from GDP growth in Japan in IVQ2013. Net trade deducted 0.8 percentage points from GDP growth of Japan in IQ2014. Net trade added 3.3 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2014. Net trade added 0.6 percentage points to GDP growth in IIIQ2014 and added 1.4 percentage points in IVQ2014. Net trade added 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2015 and deducted 1.6 percentage points in IIQ2015. Net trade added 0.8 percentage points to GDP growth in IIIQ2015 and added 0.2 percentage points in IVQ2015. Net trade added 0.5 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2016 and deducted 1.0 percentage points in IIQ2016.

- China. In Oct 2016, China exports decreased 7.3 percent relative to a year earlier and imports decreased 1.4 percent.

- Germany. Germany’s exports decreased 0.7 percent in the month of Sep 2016 and increased 0.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2016. Germany’s imports decreased 0.5 percent in the month of Sep 2016 and decreased 1.4 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2016. Net trade contributed 0.8 percentage points to growth of GDP in IQ2012, contributed 0.4 percentage points in IIQ2012, contributed 0.3 percentage points in IIIQ2012, deducted 0.5 percentage points in IVQ2012, deducted 0.3 percentage points in IQ2013 and added 0.1 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded deducted 0.5 percentage points from Germany’s GDP growth in IIIQ2013 and added 0.5 percentage points to GDP growth in IVQ2013. Net trade contributed 0.0 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2014. Net trade added 0.2 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2014 and added 0.5 percentage points in IIIQ2014. Net trade deducted 0.3 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2014 and deducted 0.1 percentage points in IQ2015. Net trade added 0.6 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2015 and deducted 0.5 percentage points in IIIQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.6 percentage points in IVQ2015 and added 0.3 percentage points in IQ2016. Net trade added 0.6 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2016.

- United Kingdom. Net trade contributed 0.7 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.7 percentage points from UK growth. Net trade contributed 0.1 percentage points to UK value added in IVQ2013. Net trade contributed 0.8 percentage points to UK value added in IQ2014 and 0.3 percentage points in IIQ2014. Net trade deducted 0.7 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2014 and added 0.3 percentage points in IVQ2014. Net traded deducted 0.6 percentage points from growth in IQ2015. Net trade added 0.2 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2015 and deducted 0.3 percentage points in IIIQ2015. Net trade added 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in IVQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.0 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2016. Net trade deducted 0.8 percentage points from GDP growth in IIQ2016.

- France. France’s exports decreased 2.2 percent in Sep 2016 while imports decreased 0.6 percent. France’s exports increased 0.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2016 and imports increased 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. Net traded added 0.1 percentage points to France’s GDP in IIIQ2012 and 0.1 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade deducted 0.1 percentage points from France’s GDP growth in IQ2013 and added 0.3 percentage points in IIQ2013, deducting 1.7 percentage points in IIIQ2013. Net trade added 0.1 percentage points to France’s GDP in IVQ2013 and deducted 0.1 percentage points in IQ2014. Net trade deducted 0.2 percentage points from France’s GDP growth in IIQ2014 and deducted 0.2 percentage points in IIIQ2014. Net trade added 0.2 percentage points to France’s GDP growth in IVQ2014 and deducted 0.2 percentage points in IQ2015. Net trade added 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2015 and deducted 0.6 percentage points in IIIQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.5 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2015 and deducted 0.2 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2016. Net trade added 0.6 percentage points to GDP in IIQ2016.

- United States. US exports increased 0.6 percent in Sep 2016 and goods exports decreased 5.0 percent in Jan-Sep 2016 relative to a year earlier. Imports decreased 1.3 percent in Sep 2016 and goods imports decreased 4.1 percent in Jan-Sep 2016 relative to a year earlier. Net trade added 0.28 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2012 and added 0.16 percentage points in IIIQ2012 and 0.58 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade added 0.30 percentage points to US GDP growth in IQ2013 and deducted 0.21 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded added 0.13 percentage points to US GDP growth in IIIQ2013. Net trade added 1.29 percentage points to US GDP growth in IVQ2013. Net trade deducted 1.16 percentage points from US GDP growth in IQ2014 and deducted 0.41 percentage points in IIQ2014. Net trade added 0.50 percentage points to GDP growth in IIIQ2014. Net trade deducted 1.14 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2014 and deducted 1.65 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.08 percentage points from GDP growth in IIQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.52 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2015. Net trade deducted 0.45 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2015. Net trade added 0.01 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2016. Net trade added 0.18 percentage points to GDP growth in IIQ2016. Net trade added 0.83 percentage points to GDP growth in IIIQ2016. Industrial production changed 0.0 percent in Oct 2016 and decreased 0.2 percent in Sep 2016 after decreasing 0.1 percent in Aug 2016, with all data seasonally adjusted, as shown in Table I-1. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System conducted the annual revision of industrial production released on Apr 1, 2016 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm):

“The Federal Reserve has revised its index of industrial production (IP) and the related measures of capacity and capacity utilization.[1] Total IP is now reported to have increased about 2 1/2 percent per year, on average, from 2011 through 2014 before falling 1 1/2 percent in 2015.[2] Relative to earlier reports, the current rates of change are lower, especially for 2014 and 2015. Total IP is now estimated to have returned to its pre-recession peak in November 2014, six months later than previously estimated. Capacity for total industry is now reported to have increased about 2 percent in 2014 and 2015 after having increased only 1 percent in 2013. Compared with the previously reported estimates, the gain in 2015 is 1/2 percentage point higher, and the gain in 2013 is 1/2 percentage point lower. Industrial capacity is expected to increase 1/2 percent in 2016.”

- Manufacturing fell 22.3 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increased 16.0 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2015. Manufacturing grew 19.6 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Oct 2016. Manufacturing in Oct 2016 is lower by 7.1 percent relative to the peak in Jun 2007. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2016 would have accumulated to 29.5 percent. GDP in IIQ2016 would be $19,414.4 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2712.3 billion than actual $16,702.1 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 23.4 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment/underemployment of 13.9 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html). US GDP in IIIQ2016 is 14.0 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,702.1 billion in IIIQ2016 or 11.4 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent. Professor John H. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. Cochrane (2016May02) measures GDP growth in the US at average 3.5 percent per year from 1950 to 2000 and only at 1.76 percent per year from 2000 to 2015 with only at 2.0 percent annual equivalent in the current expansion. Cochrane (2016May02) proposes drastic changes in regulation and legal obstacles to private economic activity. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Oct 1919 to Oct 2016. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.2316 in Dec 2007 to 141.6752 in Oct 2016. The actual index NSA in Oct 2016 is 104.5714, which is 26.2 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.1 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2015. Using trend growth of 2.1 percent per year, the index would increase to 130.0944 in Oct 2016. The output of manufacturing at 104.5714 in Oct 2016 is 19.6 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table V-4, Growth of Trade and Contributions of Net Trade to GDP Growth, ∆% and % Points

| Exports | Exports 12 M ∆% | Imports | Imports 12 M ∆% | |

| USA | 0.6 Sep | -5.0 Jan-Sep | -1.3 Sep | -4.1 Jan-Sep |

| Japan | Aug 2016 9.6 Jul 2016 -14.0 Jun 2016 -7.8 May 2016 -11.3 Apr 2016 -10.1 Mar 2016 -6.8 Feb 2016 -4.0 Jan 2016 -12.9 Dec 2015 -8.0 Nov 2015 -3.3 Oct 2015 -2.1 Sep 2015 0.6 Aug 3.1 Jul 2015 7.6 Jun 2015 9.5 May 2015 2.4 Apr 8.0 Mar 8.5 Feb 2.4 Jan 17.0 Dec 12.9 Nov 4.9 Oct 9.6 Sep 6.9 Aug -1.3 Jul 3.9 Jun -2.0 May 2014 -2.7 Apr 2014 5.1 Mar 2014 1.8 Feb 2014 9.5 Jan 2014 9.5 Dec 2013 15.3 Nov 2013 18.4 Oct 2013 18.6 Sep 2013 11.5 Aug 2013 14.7 Jul 2013 12.2 Jun 2013 7.4 May 2013 10.1 Apr 2013 3.8 Mar 2013 1.1 Feb 2013 -2.9 Jan 2013 6.4 Dec -5.8 Nov -4.1 Oct -6.5 Sep -10.3 Aug -5.8 Jul -8.1 | Aug 2016 -17.3 Jul 2016 -24.7 Jun 2016 -18.8 May 2016 -13.8 Apr 2016 -23.3 Mar 2016 -14.9 Feb 2016 -14.2 Jan 2016 -18.0 Dec 2015 -18.0 Nov 2015 -10.2 Oct 2015 -13.4 Sep 2015 -11.1 Aug -3.1 Jul 2015 -3.2 Jun 2015 -2.9 May 2015 -8.7 Apr -4.2 Mar -14.5 Feb -3.6 Jan -9.0 Dec 1.9 Nov -1.7 Oct 2.7 Sep 6.2 Aug -1.5 Jul 2.3 Jun 8.4 May 2014 -3.6 Apr 2013 3.4 Mar 2014 18.1 Feb 2014 9.0 Jan 2014 25.0 Dec 2013 24.7 Nov 2013 21.1 Oct 2013 26.1 Sep 2013 16.5 Aug 2013 16.0 Jul 2013 19.6 Jun 2013 11.8 May 2013 10.0 Apr 2013 9.4 Mar 2013 5.5 Feb 2013 7.3 Jan 2013 7.3 Dec 1.9 Nov 0.8 Oct -1.6 Sep 4.1 Aug -5.4 Jul 2.1 | ||

| China | Jan-Dec 2015 -2.8 | 2016 Oct -7.3 Sep -10.0 Aug -2.8 Jul -4.4 Jun -4.8 May -4.1 Apr -1.8 Mar 11.5 Feb -25.4 Jan -11.2 2015 -1.4 Dec -6.8 Nov -6.9 Oct -3.7 Sep -5.5 Aug -8.3 Jul 2.8 Jun -2.5 May -6.4 Apr -15.0 Mar 48.3 Feb -3.3 Jan 2014 9.7 Dec 4.7 Nov 11.6 Oct 15.3 Sep 9.4 Aug 14.5 Jul 7.2 Jun 7.0 May 0.9 Apr -6.6 Mar -18.1 Feb 10.6 Jan 2013 4.3 Dec 12.7 Nov 5.6 Oct -0.3 Sep 7.2 Aug 5.1 Jul -3.1 Jun 1.0 May 14.7 Apr 10.0 Mar 21.8 Feb 25.0 Jan | Jan-Dec 2015 -14.1 | 2016 Oct -1.4 Sep -1.9 Aug 1.5 Jul -12.5 Jun -2.8 May -0.4 Apr -10.6 Mar -7.6 Feb -13.8 Jan -18.8 2015 -7.6 Dec -8.7 Nov -18.8 Oct -20.4 Sep -13.8 Aug -8.1 Jul -6.1 Jun -17.6 May -12.7 Mar -20.5 Feb -19.9 Jan 2014 -2.4 Dec -6.7 Nov 4.6 Oct 7.0 Sep -2.4 Aug -1.6 Jul 5.5 Jun -1.6 May -0.8 Apr -11.3 Mar 10.1 Feb 10.0 Jan 2013 8.3 Dec 5.3 Nov 7.6 Oct 7.4 Sep 7.0 Aug 10.9 Jul -0.7 Jun -0.3 May 16.8 Apr 14.1 Mar -15.2 Feb 28.8 Jan |

| Euro Area | -9.8 12-M Sep | -2.1 Jan-Sep | -8.0 12-M Sep | -4.2 Jan-Sep |

| Germany | -0.7 Sep CSA | 0.9 Sep | -0.5 Sep CSA | -1.4 Sep |

| France Sep | -2.2 | -0.9 | -0.6 | 1.8 |

| Italy Sep | -1.6 | 3.1 | -4.5 | -2.7 |

| UK | -0.4 Sep | 9.4 Jul 16-Sep 16 /Jul 15-Sep 15 | 2.5 Aug | 9.5 Jul 16-Sep 16 /Jul 15-Sep 15 |

| Net Trade % Points GDP Growth | Points | |||

| USA | IIIQ2016 0.83 IIQ2016 0.18 IQ2016 0.01 IVQ2015 -0.45 IIIQ2015 -0.52 IIQ2015 -0.08 IQ2015 -1.65 IVQ2014 -1.14 IIIQ2014 0.50 IIQ2014 -0.41 IQ2014 -1.16 IVQ2013 1.29 IIIQ2013 0.13 IIQ2013 -0.21 IQ2013 0.30 IVQ2012 +0.58 IIIQ2012 0.16 IIQ2012 0.28 IQ2012 -0.02 | |||

| Japan | 0.3 IQ2012 -1.7 IIQ2012 -1.8 IIIQ2012 -0.5 IVQ2012 1.8 IQ2013 -0.5 IIQ2013 -1.3 IIIQ2013 -1.9 IVQ2013 -0.8 IQ2014 3.3 IIQ2014 0.6 IIIQ2014 1.4 IVQ2014 0.4 IQ2015 -1.6 IIQ2015 0.8 IIIQ2015 0.2 IVQ2015 0.5 IQ2016 -1.0 IIQ2016 | |||

| Germany | IQ2012 0.8 IIQ2012 0.4 IIIQ2012 0.3 IVQ2012 -0.5 IQ2013 -0.3 IIQ2013 0.1 IIIQ2013 -0.5 IVQ2013 0.5 IQ2014 0.0 IIQ2014 0.2 IIIQ2014 0.5 IVQ2014 -0.3 IQ2015 -0.1 IIQ2015 0.6 IIIQ2015 -0.5 IVQ2015 -0.6 IQ2016 0.3 IIQ2016 0.6 | |||

| France | 0.1 IIIQ2012 0.1 IVQ2012 -0.1 IQ2013 0.3 IIQ2013 -1.7 IIIQ2013 0.1 IVQ2013 -0.1 IQ2014 -0.2 IIQ2014 -0.2 IIIQ2014 0.2 IVQ2014 -0.2 IQ2015 0.4 IIQ2015 -0.6 IIIQ2015 -0.5 IVQ2015 -0.2 IQ2016 0.6 IIQ2016 -0.5 IIIQ2016 | |||

| UK | 0.7 IIQ2013 -1.7 IIIQ2013 0.1 IVQ2013 0.8 IQ2014 0.3 IIQ2014 -0.7 IIIQ2014 0.3 IVQ2014 -0.6 IQ2015 0.2 IIQ2015 -0.3 IIIQ2015 0.4 IVQ2015 0.0 IQ2016 -0.8 IIQ2016 |

Sources: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/

The geographical breakdown of exports and imports of Japan with selected regions and countries is in Table V-5 for Aug 2016. The share of Asia in Japan’s trade is close to one-half for 55.1 percent of exports and 49.3 percent of imports. Within Asia, exports to China are 18.2 percent of total exports and imports from China 24.6 percent of total imports. While exports to China decreased 8.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug 2016, imports from China decreased 15.4 percent. The largest export market for Japan in Aug 2016 is the US with share of 18.3 percent of total exports, which is close to that of China, and share of imports from the US of 11.4 percent in total imports. Japan’s exports to the US decreased 14.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug 2016 and imports from the US decreased 9.5 percent. Western Europe has share of 11.5 percent in Japan’s exports and of 13.5 percent in imports. Rates of growth of exports of Japan in Aug 2016 are minus 14.5 percent for exports to the US, minus 32.7 percent for exports to Brazil and minus 6.0 percent for exports to Germany. Comparisons relative to 2011 may have some bias because of the effects of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Deceleration of growth in China and the US and threat of recession in Europe can reduce world trade and economic activity. Growth rates of imports in the 12 months ending in Aug 2016 are mixed. Imports from Asia decreased 13.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug 2016 while imports from China decreased 15.4 percent. Data are in millions of yen, which may have effects of recent depreciation of the yen relative to the United States dollar (USD) and revaluation of the dollar relative to the euro.

Table V-5, Japan, Value and 12-Month Percentage Changes of Exports and Imports by Regions and Countries, ∆% and Millions of Yen

| Aug 2016 | Exports | 12 months ∆% | Imports Millions Yen | 12 months ∆% |

| Total | 5,316,351 | -9.6 | 5,335,062 | -17.3 |

| Asia | 2,927,184 % Total 55.1 | -9.4 | 2,629,137 % Total 49.3 | -13.8 |

| China | 968,944 % Total 18.2 | -8.9 | 1,312,115 % Total 24.6 | -15.4 |

| USA | 971,451 % Total 18.3 | -14.5 | 609,098 % Total 11.4 | -9.5 |

| Canada | 66,604 | 0.3 | 74,984 | -21.3 |

| Brazil | 25,941 | -32.7 | 46,561 | -34.4 |

| Mexico | 92,596 | -10.4 | 47,852 | 7.9 |

| Western Europe | 609,456 % Total 11.5 | 0.9 | 717,721 % Total 13.5 | -11.6 |

| Germany | 144,557 | -6.0 | 199,599 | -10.9 |

| France | 52,560 | 25.6 | 82,557 | 0.5 |

| UK | 109,276 | 11.9 | 55,613 | -16.3 |

| Middle East | 193,217 | -14.8 | 586,331 | -29.5 |

| Australia | 140,911 | 0.5 | 259,330 | -25.6 |

Source: Japan, Ministry of Finance http://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/index_e.htm

World trade projections of the IMF are in Table V-6. There is decreasing growth of the volume of world trade of goods and services from 2.6 percent in 2015 to 2.3 percent in 2016, increasing to 3.8 percent in 2017. Growth improves to 4.1 percent on average from 2017 to 2021. World trade would be slower for advanced economies while emerging and developing economies (EMDE) experience faster growth. World economic slowdown would be more challenging with lower growth of world trade.

Table V-6, IMF, Projections of World Trade, USD Billions, USD/Barrel and Annual ∆%

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average ∆% 2017-2021 | |

| World Trade Volume (Goods and Services) | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 |

| Exports Goods & Services | 2.7 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Imports Goods & Services | 2.4 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| Average Oil Price USD/Barrel | 50.79 | 42.96 | 50.64 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 79.16 |

| Average Annual ∆% Export Unit Value of Manufactures | -2.9 | -2.1 | 1.4 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 0.4 |

| Exports of Goods & Services | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 |

| EMDE | 1.3 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| G7 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| Imports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -0.6 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| G7 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -4.1 | -1.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| G7 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods | ||||

| EMDE | -4.0 | -1.0 | 0.1 | -0.1 |

| G7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

Notes: Commodity Price Index includes Fuel and Non-fuel Prices; Commodity Industrial Inputs Price includes agricultural raw materials and metal prices; Oil price is average of WTI, Brent and Dubai

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The JP Morgan Global All-Industry Output Index of the JP Morgan Manufacturing and Services PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and HIS Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, with high association with world GDP, increased to 53.3 in Oct from 51.7 in Sep, indicating expansion at the rate (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/dffc698018984829af58ec503a114e9d). This index has remained above the contraction territory of 50.0 during 47 consecutive months. The employment index increased from 50.6 in Sep to 50.9 in Oct with input prices rising at faster rate, new orders increasing at faster rate and output increasing at faster rate (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/dffc698018984829af58ec503a114e9d). David Hensley, Director of Global Economic Coordination at JP Morgan, finds moderate growth with recent improvement (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/dffc698018984829af58ec503a114e9d). The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, increased to 52.0 in Oct from 51.0 in Sep (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/ed078da8ffb0443593d4ffa2bffd8de9). New export orders increased. David Hensley, Director of Global Economic Coordination at JP Morgan, higher growth (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/ed078da8ffb0443593d4ffa2bffd8de9). The Markit Brazil Composite Output Index decreased from 46.1 in Sep to 44.9 in Oct, indicating contraction in activity of Brazil’s private sector (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/e93a402c92ff4ee19c7a214dab7aa977). The Markit Brazil Services Business Activity index, compiled by Markit, decreased from 45.3 in Sep to 43.9 in Oct, indicating contracting services activity (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/e93a402c92ff4ee19c7a214dab7aa977). Pollyanna de Lima, Economist at Markit, finds continuing weakness (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/e93a402c92ff4ee19c7a214dab7aa977). The Markit Brazil Purchasing Managers’ IndexTM (PMI™) increased from 46.0 in Sep to 46.3 in Oct, indicating contraction in manufacturing (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5346bb35700c48d682490e93548e6a4c). Pollyanna De Lima, Economist at IHS Markit, finds contraction in manufacturing (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5346bb35700c48d682490e93548e6a4c).

VA United States. The Markit Flash US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) seasonally adjusted increased to 53.2 in Oct from 51.5 in Sep (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/8e4b24e60ba0430ca4cde48da4915c08). New export orders increased. Chris Williamson, Senior Business Economist at IHS Markit, finds improvement with challenges (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/8e4b24e60ba0430ca4cde48da4915c08). The Markit Flash US Services PMI™ Business Activity Index increased from 52.3 in Sep to 54.8 in Oct (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/ff0a88d04891402fa6ce739c8b1b2db2). The Markit Flash US Composite PMI™ Output Index increased from 52.3 in Sep to 54.9 in Oct. Tim Moore, Senior Economist at IHS Markit, finds that the surveys are consistent with growth at around 2.0 percent in IVQ2016 (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/ff0a88d04891402fa6ce739c8b1b2db2). The Markit US Composite PMI™ Output Index of Manufacturing and Services increased to 54.9 in Oct from 52.3 in Sep (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/1ad0a291b1c2475c9592acedd84595c5). The Markit US Services PMI™ Business Activity Index increased from 52.3 in Sep to 54.8 in Oct (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/1ad0a291b1c2475c9592acedd84595c5). Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at IHS Markit, finds the indexes suggesting faster economic growth (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/1ad0a291b1c2475c9592acedd84595c5). The Markit US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) increased to 53.4 in Oct from 51.5 in Sep (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/4f0a49e69e2b4681a90fbff2bcc9b4a3). New foreign orders increased. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds improving manufacturing (https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/4f0a49e69e2b4681a90fbff2bcc9b4a3). The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) of the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Report on Business® increased 0.4-percentage points from 51.5 in Sep to 51.9 in Oct, which indicates faster growth (https://www.instituteforsupplymanagement.org/ismreport/mfgrob.cfm?SSO=1). The index of new orders decreased 3.0 percentage points from 55.1 in Sep to 52.1 in Oct. The index of new exports increased 0.5 percentage points from 52.0 in Sep to 52.5 in Oct, expanding at faster rate. The Non-Manufacturing ISM Report on Business® PMI decreased 2.3 percentage points from 57.1 in Sep to 54.8 in Oct, indicating growth of business activity/production during 87 consecutive months, while the index of new orders decreased 2.3 percentage points from 60.0 in Sep to 57.7 in Oct (https://www.instituteforsupplymanagement.org/ISMReport/NonMfgROB.cfm?navItemNumber=30620). Table USA provides the country economic indicators for the US.

Table USA, US Economic Indicators

| Consumer Price Index | Oct 12 months NSA ∆%: 1.6; ex food and energy ∆%: 2.1 Oct month SA ∆%: 0.4; ex food and energy ∆%: 0.1 |

| Producer Price Index | Finished Goods Oct 12-month NSA ∆%: 0.6; ex food and energy ∆% 1.6 Final Demand Oct 12-month NSA ∆%: 0.8; ex food and energy ∆% 1.2 |

| PCE Inflation | Sep 12-month NSA ∆%: headline 1.2; ex food and energy ∆% 1.7 |

| Employment Situation | Household Survey: Oct Unemployment Rate SA 4.9% |

| Nonfarm Hiring | Nonfarm Hiring fell from 63.3 million in 2006 to 58.7 million in 2014 or by 4.7 million and to 61.7 million in 2015 or by 1.7 million |

| GDP Growth | BEA Revised National Income Accounts IIQ2012/IIQ2011 2.5 IIIQ2012/IIIQ2011 2.4 IVQ2012/IVQ2011 1.3 IQ2013/IQ2012 1.3 IIQ2013/IIQ2012 1.0 IIIQ2013/IIIQ2012 1.7 IVQ2013/IVQ2012 2.7 IQ2014/IQ2013 1.6 IIQ2014/IIQ2013 2.4 IIIQ2014/IIIQ2013 2.9 IVQ2014/IVQ2013 2.5 IQ2015/IQ2014 3.3 IIQ2015/IIQ2014 3.0 IIIQ2015/IIIQ2014 2.2 IVQ2015/IVQ2014 1.9 IQ2016/IQ2015 1.6 IIQ2016/IIQ2015 1.3 IIIQ2016/IIIQ2015: 1.5 IQ2012 SAAR 2.7 IIQ2012 SAAR 1.9 IIIQ2012 SAAR 0.5 IVQ2012 SAAR 0.1 IQ2013 SAAR 2.8 IIQ2013 SAAR 0.8 IIIQ2013 SAAR 3.1 IVQ2013 SAAR 4.0 IQ2014 SAAR -1.2 IIQ2014 SAAR 4.0 IIIQ2014 SAAR 5.0 IVQ2014 SAAR 2.3 IQ2015 SAAR 2.0 IIQ2015 SAAR: 2.6 IIIQ2015 SAAR: 2.0 IVQ2015 SAAR: 0.9 IQ2016 SAAR: 0.8 IIQ2016 SAAR: 1.4 IIIQ2016 SAAR: 2.9 |

| Real Private Fixed Investment | SAAR IIIQ2016 ∆% -0.6 IVQ2007 to IIIQ2016: 7.3% Blog 10/30/16 |

| Corporate Profits | IIQ2016 SAAR: Corporate Profits -0.6; Undistributed Profits -3.6 Blog 10/2/16 |

| Personal Income and Consumption | Sep month ∆% SA Real Disposable Personal Income (RDPI) SA ∆% 0.0 |

| Quarterly Services Report | IIQ16/IQ15 NSA ∆%: Financial & Insurance 4.0 Earlier Data: |

| Employment Cost Index | Compensation Private IIIQ2016 SA ∆%: 0.5 Sep 12 months ∆%: 2.3 Earlier Data: |

| Industrial Production | Oct month SA ∆%: 0.0 Manufacturing Oct SA 0.2 ∆% Oct 12 months SA ∆% -0.2, NSA -0.1 |

| Productivity and Costs | Nonfarm Business Productivity IIIQ2016∆% SAAE 3.1; IIIQ2016/IIIQ2015 ∆% 0.0; Unit Labor Costs SAAE IIIQ2016 ∆% 0.3; IIIQ2016/IIIQ2015 ∆%: 2.3 Blog 11/6/16 |

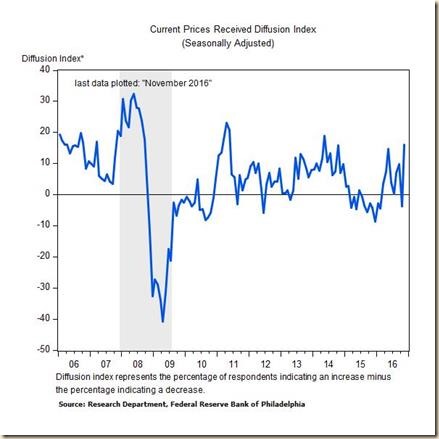

| New York Fed Manufacturing Index | General Business Conditions From Oct -6.8 to Nov 1.5 |

| Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook Index | General Index from Oct 9.7 to Nov 7.6 |

| Manufacturing Shipments and Orders | Sep Orders SA ∆% 0.3 Ex Transport 0.6 Jan-Sep 16/Jan-Sep 15 NSA New Orders ∆% minus 2.3 Ex transport minus 2.9 Earlier data: |

| Durable Goods | Sep New Orders SA ∆%: -0.1; ex transport ∆%: 0.2 Earlier Data: |

| Sales of New Motor Vehicles | Oct 2016 14,479,364; Oct 2015 14,508,727. Oct 16 SAAR 18.02 million, Sep 16 SAAR 17.76 million, Oct 2015 SAAR 18.18 million Blog 11/6/16 |

| Sales of Merchant Wholesalers | Jan-Sep 2016/Jan-Sep 2015 NSA ∆%: Total -1.2; Durable Goods: minus 0.2; Nondurable EARLIER DATA: |

| Sales and Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers | Sep 16 12-M NSA ∆%: Sales Total Business 1.0; Manufacturers -0.6 |

| Sales for Retail and Food Services | Jan-Oct 2016/Jan-Oct 2015 ∆%: Retail and Food Services 2.9; Retail ∆% 2.5 |

| Value of Construction Put in Place | SAAR month SA Sep ∆%: minus 0.4 Jan-Sep 16/Jan-Sep 15 NSA: 4.4 Earlier Data: |

| Case-Shiller Home Prices | Aug 2016/ Aug 2015 ∆% NSA: 10 Cities 4.3; 20 Cities: 5.1; National: 5.3 |

| FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only | Aug SA ∆% 0.7; |

| New House Sales | Sep 2016 month SAAR ∆%: 3.1 |

| Housing Starts and Permits | Oct Starts month SA ∆% 25.5; Permits ∆%: 0.3 Earlier Data: |

| Rate of Homeownership | IIQ2016: 63.5 Blog 10/30/16 |

| Trade Balance | Balance Sep SA -$36,440 million versus Aug -$40,462 million |

| Export and Import Prices | Oct 12-month NSA ∆%: Imports -0.2; Exports -1.1 Earlier Data: |

| Consumer Credit | Sep ∆% annual rate: Total 6.3; Revolving 5.2; Nonrevolving 6.7 Earlier Data: |

| Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term Treasury Securities | Sep Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term US Securities: minus $63.3 billion |

| Treasury Budget | Fiscal Year 2017/2016 ∆% Oct: Receipts 5.0; Outlays minus 23.5; Individual Income Taxes 11.3 Deficit Fiscal Year 2012 $1,087 billion Deficit Fiscal Year 2013 $680 billion Deficit Fiscal Year 2014 $485 billion Deficit Fiscal Year 2015 $438 billion Deficit Fiscal Year 2016 $587 Blog 11/13/2016 |

| CBO Budget and Economic Outlook | 2012 Deficit $1087 B 6.8% GDP Debt $11,281 B 70.4% GDP 2013 Deficit $680 B, 4.1% GDP Debt $11,983 B 72.6% GDP 2014 Deficit $485 B 2.8% GDP Debt $12,780 B 74.4% GDP 2015 Deficit $438 B 2.5% GDP Debt $13,117 B 73.6% GDP 2026 Deficit $1,343B, 4.9% GDP Debt $23,672B 85.6% GDP 2046: Long-term Debt/GDP 141.1% Blog 8/26/12 11/18/12 2/10/13 9/22/13 2/16/14 8/24/14 9/14/14 3/1/15 6/21/15 1/3/16 4/10/16 7/24/16 |

| Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities | Sep 2016 SAAR ∆%: Securities 12.3 Loans 7.3 Cash Assets -40.1 Deposits minus 0.9 Blog 10/23/16 |

| Flow of Funds Net Worth of Families and Nonprofits | IIQ2016 ∆ since 2007 Assets +$22,869.5 BN Nonfinancial 3346.9 BN Real estate $2331.3 BN Financial +19,522.5 BN Net Worth +$22,577.4 BN Blog 9/25/16 |

| Current Account Balance of Payments | IIQ2016 -108,806 MM % GDP 2.6 Blog 9/25/16 |

| Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation | Blog 11/13/16 |

| IMF View | World Real Economic Growth 2016 ∆% 3.1 Blog 10/16/16 |

| Income, Poverty and Health Insurance in the United States | 43.123 Million Below Poverty in 2015, 13.5% of Population Median Family Income CPI-2015 Adjusted $56,516 in 2015 back to 1999 Levels Uncovered by Health Insurance 28.966 Million in 2015 Blog 9/25/16 |

| Monetary Policy and Cyclical Valuation of Risk Financial Assets | Blog 1/17/2016 |

Links to blog comments in Table USA: 11/13/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/dollar-revaluation-and-valuations-of.html

11/6/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html

10/30/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states_30.html

10/23/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html

10/16/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html

10/9/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html

10/2/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html

9/25/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html

9/4/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html

7/31/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/business-fixed-investment-has-been-soft.html

7/24/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html

4/10/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html

1/17/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html

1/3/16 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html

10/11/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-imf.html

6/21/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html

5/10/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/quite-high-equity-valuations-and.html

4/26/2015 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/imf-view-of-economy-and-finance-united.html

4/19/2015 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html

4/12/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/dollar-revaluation-recovery-without.html

4/5/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html

3/22/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html

3/1/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html

2/1/15 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/financial-and-international.html

9/14/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitics-monetary-policy-and.html

8/24/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html

2/16/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html

9/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

2/10/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

Table VA-1 provides the value of total sales of US business (manufacturers, retailers and merchant wholesalers) and monthly and 12-month percentage changes. Sales of manufacturers increased 0.8 percent in Sep and increased 0.2 percent in Aug, decreasing 0.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2016. Sales of retailers increased 1.0 percent in Sep, decreased 0.1 percent in Aug and increased 3.5 percent in 12 months. Sales of merchant wholesalers increased 0.2 percent in Sep, increasing 0.7 percent in Aug and increasing 0.5 percent in 12 months. Total business sales increased 0.7 percent in Sep and increased 0.3 percent in Aug, increasing 1.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2016.

Table VA-1, US, Percentage Changes for Sales of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers

| Sep 16/Aug 16 | Aug 2016 | Aug 16/Jul 16 ∆% SA | Sep 16/ Sep 15 | |

| Total Business | 0.7 | 1,334,703 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Manufacturers | 0.8 | 484,622 | 0.2 | -0.6 |

| Retailers | 1.0 | 393,467 | -0.1 | 3.5 |

| Merchant Wholesalers | 0.2 | 456,614 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

Source: US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/mtis/

US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/mtis/

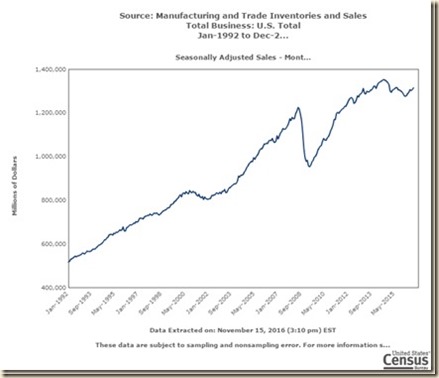

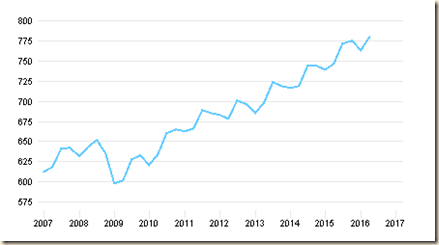

Chart VA-1 of the US Census Bureau provides total US sales of manufacturing, retailers and wholesalers seasonally adjusted (SA) in millions of dollars. The series with adjustment evens fluctuations following seasonal patterns. There is sharp recovery from the global recession in a robust trend, which is mixture of price and quantity effects because data are not adjusted for price changes. There is stability in the final segment with subdued prices with data not adjusted for price changes.

Chart VA-1, US, Total Business Sales of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers, SA, Millions of Dollars, Jan 1992-Sep 2016

US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/mtis/

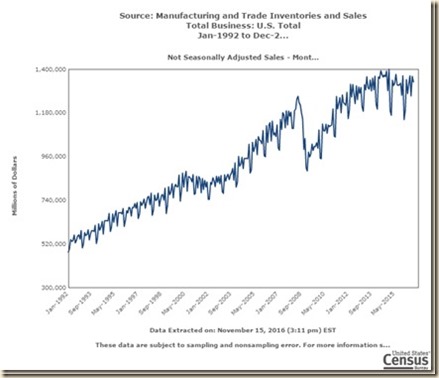

Chart VA-2 of the US Census Bureau provides total US sales of manufacturing, retailers and wholesalers not seasonally adjusted (NSA) in millions of dollars. The series without seasonal adjustment shows sharp jagged behavior because of monthly fluctuations following seasonal patterns. There is sharp recovery from the global recession in a robust trend, which is mixture of price and quantity effects because data are not adjusted for price changes. There is stability in the final segment with monthly marginal weakness in data without adjustment for price changes.

Chart VA-2, US, Total Business Sales of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers, NSA, Millions of Dollars, Jan 1992-Sep 2016

US Census Bureau

Businesses added cautiously to inventories to replenish stocks. Retailers’ inventories increased 0.2 percent in Sep 2016 and increased 0.6 percent in Aug with growth of 3.8 percent in 12 months, as shown in Table VA-2. Total business increased inventories 0.1 percent in Sep, increasing 0.2 percent in Aug and increasing 0.6 percent in 12 months. Inventories sales/ratios of total business continued at a level close to 1.30 under careful management to avoid costs and risks, changing to 1.38 in Sep 2016. Inventory/sales ratios of manufacturers and retailers are higher than for merchant wholesalers. There is stability in inventory/sales ratios in individual months and relative to a year earlier with increase at the margin.

Table VA-2, US, Percentage Changes for Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers and Inventory/Sales Ratios

| Inventory Change | Sep 16 | Sep 16/ Aug 16 ∆% SA | Aug 16/Jul 16 ∆% SA | Sep 16/Sep 15 ∆% NSA |

| Total Business | 1,816,511 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Manufacturers | 621,341 | 0.0 | 0.1 | -1.9 |

| Retailers | 608,742 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 3.8 |

| Merchant | 586,428 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Inventory/ | Sep 16 | Sep 2016 SA | Aug 2016 SA | Sep 2015 SA |

| Total Business | 1,816,511 | 1.38 | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| Manufacturers | 621,341 | 1.34 | 1.35 | 1.36 |

| Retailers | 608,742 | 1.49 | 1.50 | 1.48 |

| Merchant Wholesalers | 586,428 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

US Census Bureau

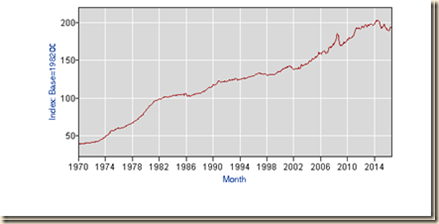

Chart VA-3 of the US Census Bureau provides total business inventories of manufacturers, retailers and merchant wholesalers seasonally adjusted (SA) in millions of dollars from Jan 1992 to Sep 2016. The impact of the two recessions of 2001 and IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 is evident in the form of sharp reductions in inventories. Inventories have surpassed the peak before the global recession. Data are not adjusted for price changes.

Chart VA-3, US, Total Business Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers, SA, Millions of Dollars, Jan 1992-Sep 2016

US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/mtis/

Chart VA-4 provides total business inventories of manufacturers, retailers and merchant wholesalers not seasonally adjusted (NSA) from Jan 1992 to Sep 2016 in millions of dollars. The recessions of 2001 and IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 are evident in the form of sharp reductions of inventories. There is sharp upward trend of inventory accumulation after both recessions. Total business inventories are higher than in the peak before the global recession.

Chart VA-4, US, Total Business Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers, NSA, Millions of Dollars, Jan 1992-Sep 2016

US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/mtis/

Inventories follow business cycles. When recession hits sales inventories pile up, declining with expansion of the economy. In a fascinating classic opus, Lloyd Meltzer (1941, 129) concludes:

“The dynamic sequences (i) through (6) were intended to show what types of behavior are possible for a system containing a sales output lag. The following conclusions seem to be the most important:

(i) An economy in which business men attempt to recoup inventory losses will always undergo cyclical fluctuations when equilibrium is disturbed, provided the economy is stable.

This is the pure inventory cycle.

(2) The assumption of stability imposes severe limitations upon the possible size of the marginal propensity to consume, particularly if the coefficient of expectation is positive.

(3) The inventory accelerator is a more powerful de-stabilizer than the ordinary acceleration principle. The difference in stability conditions is due to the fact that the former allows for replacement demand whereas the usual analytical formulation of the latter does not. Thus, for inventories, replacement demand acts as a de-stabilizer. Whether it does so for all types of capital goods is a moot question, but I believe cases may occur in which it does not.

(4) Investment for inventory purposes cannot alter the equilibrium of income, which depends only upon the propensity to consume and the amount of non-induced investment.

(5) The apparent instability of a system containing both an accelerator and a coefficient of expectation makes further investigation of possible stabilizers highly desirable.”

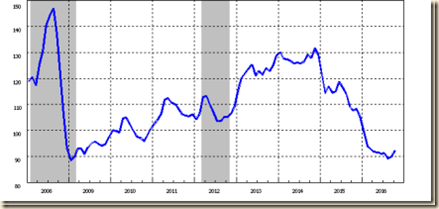

Chart VA-5 shows the increase in the inventory/sales ratios during the recession of 2007-2009. The inventory/sales ratio fell during the expansions. The inventory/sales ratio declined to a trough in 2011, climbed and then stabilized at current levels in 2012, 2013 and 2015 with increase into 2015-2016, decreasing at the margin.

Chart VA-5, Total Business Inventories/Sales Ratios 2006 to 2016

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www2.census.gov/mtis/historical/img/mtisbrf.gif

Sales of retail and food services increased 0.8 percent in Oct 2016 after increasing 1.0 percent in Sep 2016 seasonally adjusted (SA), growing 2.9 percent in Jan-Oct 2016 relative to Jan-Oct 2015 not seasonally adjusted (NSA), as shown in Table VA-3. Excluding motor vehicles and parts, retail sales increased 0.8 percent in Oct 2016, increasing 0.7 percent in Sep 2016 SA and increasing 2.8 percent NSA in Jan-Oct 2016 relative to a year earlier. Sales of motor vehicles and parts increased 1.1 percent in Oct 2016 after increasing 1.9 percent in Sep 2016 SA and increasing 3.3 percent NSA in Jan-Oct 2016 relative to a year earlier. Gasoline station sales increased 2.2 percent SA in Oct 2016 after increasing 3.0 percent in Sep 2016 in oscillating prices of gasoline that are moderating, decreasing 8.6 percent in Jan-Oct 2016 relative to a year earlier.

Table VA-3, US, Percentage Change in Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services, ∆%

| Oct/Sep ∆% SA | Sep/Aug ∆% SA | Jan 2016-Oct 2016 Million Dollars NSA | Jan-Oct 2016 from Jan-Oct 2015 ∆% NSA | |

| Retail and Food Services | 0.8 | 1.0 | 4,494,704 | 2.9 |

| Excluding Motor Vehicles and Parts | 0.8 | 0.7 | 3,552,844 | 2.8 |

| Motor Vehicles & Parts Dealers | 1.1 | 1.9 | 941,860 | 3.3 |

| Retail | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3,946,643 | 2.5 |

| Building Materials | 1.1 | 1.8 | 296,239 | 6.3 |

| Food and Beverage | 0.9 | 0.6 | 582,711 | 2.2 |

| Grocery | 0.7 | 0.6 | 522,424 | 2.1 |