“The case for an increase in the federal funds rate has continued to strengthen,” Twenty Three Million Unemployed or Underemployed, Job Creation, Stagnating Real Wages, Stagnating Real Disposable Income per Capita, Financial Repression, Rules, Discretionary Authority and Slow Productivity Growth, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016

I Twenty Three Million Unemployed or Underemployed

IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation

IA2 Number of People in Job Stress

IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment

IA4 Job Creation

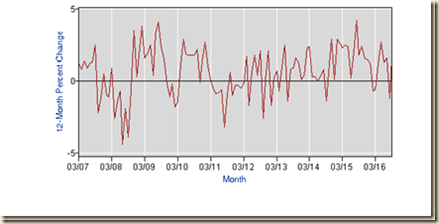

IB Stagnating Real Wages

II Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

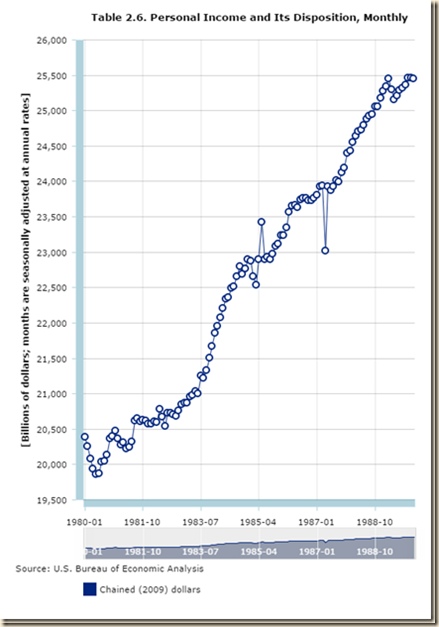

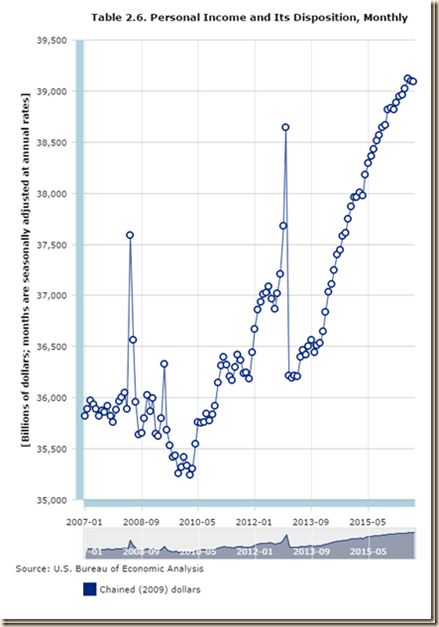

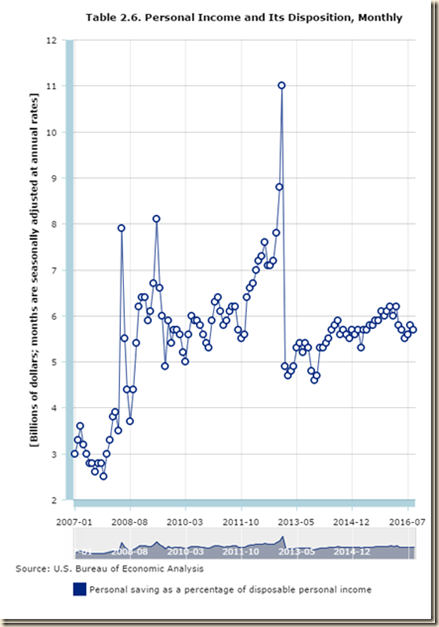

IB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

IIA Rules, Discretionary Authorities and Slow Productivity Growth

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

Executive Summary

Contents of Executive Summary

ESI Financial “Irrational Exuberance,” Increasing Interest Rate and Exchange Rate Risk, Duration Dumping, Competitive Devaluations, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk

ESII Valuations of Risk Financial Assets

ESIII Twenty-three Million Unemployed or Underemployed

ESIV Job Creation

ESV Stagnating Real Wages

ESVI Stagnating Real Disposable Income

ESVII Financial Repression

ESVIII Rules, Discretionary Authority and Slow Productivity Growth

ESIII Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars below Trend

ESIV Stagnating Real Private Fixed Investment

ESV United States Housing

ESVI Decline of United States Homeownership

ESI “Financial “Irrational Exuberance,” Increasing Interest Rate and Exchange Rate Risk, Duration Dumping, Competitive Devaluations, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task for both theory and measurement. The IMF provides surveillance of the world economy with its Global Economic Outlook (WEO) (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=29), of the world financial system with its Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/index.htm) and of fiscal affairs with the Fiscal Monitor (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=262). There appears to be a moment of transition in global economic and financial variables that may prove of difficult analysis and measurement. It is useful to consider a summary of global economic and financial risks, which are analyzed in detail in the comments of this blog in Section VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets, Table VI-4.

Economic risks include the following:

- China’s Economic Growth. The National People’s Congress of China in Mar 2016 is reducing the GDP growth target to the range of 6.5 percent to 7.0 percent in guiding stable market expectations (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/photo/2016-03/05/c_135157171.htm). President Xi Jinping announced on Nov 3, 2015 that “For China to double 2010 GDP and the per capita income of both urban and rural residents by 2010, annual growth for the 2016-2020 period must be at least 6.5 percent,” as quoted by Xinhuanet (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-11/03/c_134780377.htm). China lowered the growth target to approximately 7.0 percent in 2015, as analyzed by Xiang Bo, writing on “China lowers 2015 economic growth target to around 7 percent,” published on Xinhuanet on Mar 5, 2015 (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-03/05/c_134039341.htm). China had lowered its growth target to 7.5 percent per year. Lu Hui, writing on “China lowers GDP target to achieve quality economic growth, on Mar 12, 2012, published in Beijing by Xinhuanet (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-03/12/c_131461668.htm), informs that Premier Jiabao wrote in a government work report that the GDP growth target will be lowered to 7.5 percent to enhance the quality and level of development of China over the long term. The Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China adopted unanimously on Nov 15, 2013, a new round of reforms with 300 measures (Xinhuanet, “China details reform decision-making process,” Nov 19, 2013 http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-11/19/c_125722517.htm). Growth rates of GDP of China in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier have been declining from 2011 to 2016. China’s GDP grew 1.9 percent in IQ2012, annualizing to 7.8 percent, and 8.1 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 2.2 percent in IIQ2012, which annualizes to 9.1 percent, and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 1.8 percent in IIIQ2012, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 8.1 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 7.9 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, China grew at 1.7 percent, which annualizes at 7.0 percent, and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.1 percent in IIIQ2013, which annualizes at 8.7 percent, and increased 7.9 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 1.6 percent in IVQ2013, which annualized to 6.6 percent, and 7.7 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.7 percent in IQ2014, which annualizes to 7.0 percent, and 7.4 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.8 percent in IIQ2014, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. China’s GDP grew 1.8 percent in IIIQ2014, which is equivalent to 7.4 percent in a year, and 7.1 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.8 percent in IVQ2014, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and 7.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 1.6 percent in IQ2015, which annualizes at 6.6 percent, and 7.0 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.9 percent in IIQ2015, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and increased 7.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2015, China’s GDP grew at 1.7 percent, which annualizes at 7.0 percent, and increased 6.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew at 1.6 percent in IVQ2015, which annualizes at 6.6 percent, and increased 6.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China grew 1.2 percent in IQ2016, which annualizes at 4.9 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2016, the GDP of China increased 1.9 percent, which annualizes to 7.8 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of China increased at 1.8 percent in IIIQ2016, which annualizes at 7.4 percent, and increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. There is decennial change in leadership in China (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/index.htm). (Section VC and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/valuation-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/imf-view-of-economy-and-finance-united.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/competitive-currency-conflicts-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/financial-irrational-exuberance.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/04/imf-view-world-inflation-waves-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html). There is also ongoing political development in China during a decennial political reorganization with new leadership (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/index.htm). Xinhuanet informs that Premier Wen Jiabao considers the need for macroeconomic stimulus, arguing that “we should continue to implement proactive fiscal policy and a prudent monetary policy, while giving more priority to maintaining growth” (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-05/20/c_131599662.htm). Premier Wen elaborates that “the country should properly handle the relationship between maintaining growth, adjusting economic structures and managing inflationary expectations” (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-05/20/c_131599662.htm). Bob Davis, writing on “At China’s NPC, Proposed Changes,” on Mar 5, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304732804579420743344553328?KEYWORDS=%22china%22&mg=reno64-wsj), analyzes the wide ranging policy changes in the annual work report by Prime Minister Li Keqiang to China’s NPC (National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/news/). There are about sixty different fiscal and regulatory measures.

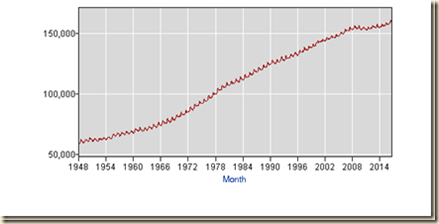

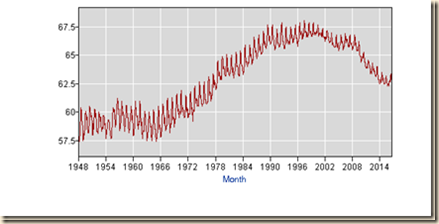

- United States Economic Growth, Labor Markets and Budget/Debt Quagmire. The US is growing slowly with 23.6 million in job stress, fewer 10 million full-time jobs, high youth unemployment, historically low hiring and declining/stagnating real wages. Actual GDP is about two trillion dollars lower than trend GDP.

- Economic Growth and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies. Advanced economies are growing slowly. There is still high unemployment in advanced economies.

- World Inflation Waves. Inflation continues in repetitive waves globally (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html). There is growing concern on capital outflows and currency depreciation of emerging markets.

A list of financial uncertainties includes:

- Euro Area Survival Risk. The resilience of the euro to fiscal and financial doubts on larger member countries is still an unknown risk. There are complex economic, financial and political effects of the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union or BREXIT after the referendum on Jun 23, 2016 (https://next.ft.com/eu-referendum for extensive coverage by the Financial Times).

- Competitive Devaluations. Exchange rate struggles continue as zero interest rates and negative interest rates in advanced economies induce devaluation of their currencies with alternating episodes of revaluation.

- Valuation and Volatility of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with oscillating volumes. The President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, warned on Jun 3, 2015 that (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2015/html/is150603.en.html):

“But certainly one lesson is that we should get used to periods of higher volatility. At very low levels of interest rates, asset prices tend to show higher volatility…the Governing Council was unanimous in its assessment that we should look through these developments and maintain a steady monetary policy stance.”

- Duration Trap of the Zero Bound. The yield of the US 10-year Treasury rose from 2.031 percent on Mar 9, 2012, to 2.294 percent on Mar 16, 2012. Considering a 10-year Treasury with coupon of 2.625 percent and maturity in exactly 10 years, the price would fall from 105.3512 corresponding to yield of 2.031 percent to 102.9428 corresponding to yield of 2.294 percent, for loss in a week of 2.3 percent but far more in a position with leverage of 10:1. Min Zeng, writing on “Treasurys fall, ending brutal quarter,” published on Mar 30, 2012, in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303816504577313400029412564.html?mod=WSJ_hps_sections_markets), informs that Treasury bonds maturing in more than 20 years lost 5.52 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

- Credibility and Commitment of Central Bank Policy. There is a credibility issue of the commitment of monetary policy (Sargent and Silber 2012Mar20)

- Carry Trades. Commodity prices driven by zero interest rates have resumed their increasing path with fluctuations caused by intermittent risk aversion mixed with reallocations of portfolios of risk financial

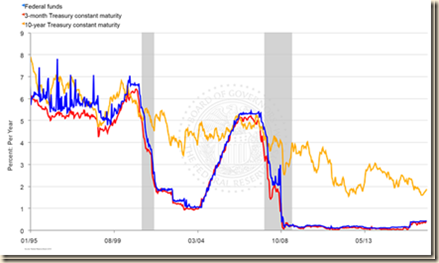

There are collateral effects of unconventional monetary policy. Chart VIII-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate on the overnight fed funds rate and the yields of the 10-year constant maturity Treasury and the Baa seasoned corporate bond. Table VIII-3 provides the data for selected points in Chart VIII-1. There are two important economic and financial events, illustrating the ease of inducing carry trade with extremely low interest rates and the resulting financial crash and recession of abandoning extremely low interest rates.

- The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target of the fed funds rate from 7.03 percent on Jul 3, 2000, to 1.00 percent on Jun 22, 2004, in pursuit of non-existing deflation (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-85). Central bank commitment to maintain the fed funds rate at 1.00 percent induced adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMS) linked to the fed funds rate. Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment. The exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at interest rates close to zero, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV). The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper with the objective of purchasing default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever-increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and worked with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity by the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions. The put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4). The FOMC implemented increments of 25 basis points of the fed funds target from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006, raising the fed funds rate to 5.25 percent on Jul 3, 2006, as shown in Chart VIII-1. The gradual exit from the first round of unconventional monetary policy from 1.00 percent in Jun 2004 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/monetary/2004/20040630/default.htm) to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20060629a.htm) caused the financial crisis and global recession.

- On Dec 16, 2008, the policy determining committee of the Fed decided (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm): “The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to establish a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent.” Policymakers emphasize frequently that there are tools to exit unconventional monetary policy at the right time. At the confirmation hearing on nomination for Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Vice Chair Yellen (2013Nov14 http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20131114a.htm), states that: “The Federal Reserve is using its monetary policy tools to promote a more robust recovery. A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases. I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.” Perception of withdrawal of $2671 billion, or $2.7 trillion, of bank reserves (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1), would cause Himalayan increase in interest rates that would provoke another recession. There is no painless gradual or sudden exit from zero interest rates because reversal of exposures created on the commitment of zero interest rates forever.

In his classic restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958, 86):

“The assumption that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates and differ from each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

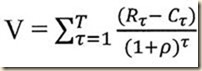

Tobin (1969) provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus, g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Friedman 1957). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

Dan Strumpf and Pedro Nicolaci da Costa, writing on “Fed’s Yellen: Stock Valuations ‘Generally are Quite High,’” on May 6, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-yellen-cites-progress-on-bank-regulation-1430918155?tesla=y ), quote Chair Yellen at open conversation with Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, finding “equity-market valuations” as “quite high” with “potential dangers” in bond valuations. The DJIA fell 0.5 percent on May 6, 2015, after the comments and then increased 0.5 percent on May 7, 2015 and 1.5 percent on May 8, 2015.

| Fri May 1 | Mon 4 | Tue 5 | Wed 6 | Thu 7 | Fri 8 |

| DJIA 18024.06 -0.3% 1.0% | 18070.40 0.3% 0.3% | 17928.20 -0.5% -0.8% | 17841.98 -1.0% -0.5% | 17924.06 -0.6% 0.5% | 18191.11 0.9% 1.5% |

There are two approaches in theory considered by Bordo (2012Nov20) and Bordo and Lane (2013). The first approach is in the classical works of Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz (1963a, 1987) and Karl Brunner and Allan H. Meltzer (1973). There is a similar approach in Tobin (1969). Friedman and Schwartz (1963a, 66) trace the effects of expansionary monetary policy into increasing initially financial asset prices: “It seems plausible that both nonbank and bank holders of redundant balances will turn first to securities comparable to those they have sold, say, fixed-interest coupon, low-risk obligations. But as they seek to purchase these they will tend to bid up the prices of those issues. Hence they, and also other holders not involved in the initial central bank open-market transactions, will look farther afield: the banks, to their loans; the nonbank holders, to other categories of securities-higher risk fixed-coupon obligations, equities, real property, and so forth.”

The second approach is by the Austrian School arguing that increases in asset prices can become bubbles if monetary policy allows their financing with bank credit. Professor Michael D. Bordo provides clear thought and empirical evidence on the role of “expansionary monetary policy” in inflating asset prices (Bordo2012Nov20, Bordo and Lane 2013). Bordo and Lane (2013) provide revealing narrative of historical episodes of expansionary monetary policy. Bordo and Lane (2013) conclude that policies of depressing interest rates below the target rate or growth of money above the target influences higher asset prices, using a panel of 18 OECD countries from 1920 to 2011. Bordo (2012Nov20) concludes: “that expansionary money is a significant trigger” and “central banks should follow stable monetary policies…based on well understood and credible monetary rules.” Taylor (2007, 2009) explains the housing boom and financial crisis in terms of expansionary monetary policy. Professor Martin Feldstein (2016), at Harvard University, writing on “A Federal Reserve oblivious to its effects on financial markets,” on Jan 13, 2016, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/a-federal-reserve-oblivious-to-its-effect-on-financial-markets-1452729166), analyzes how unconventional monetary policy drove values of risk financial assets to high levels. Quantitative easing and zero interest rates distorted calculation of risks with resulting vulnerabilities in financial markets.

Another hurdle of exit from zero interest rates is “competitive easing” that Professor Raghuram Rajan, governor of the Reserve Bank of India, characterizes as disguised “competitive devaluation” (http://www.centralbanking.com/central-banking-journal/interview/2358995/raghuram-rajan-on-the-dangers-of-asset-prices-policy-spillovers-and-finance-in-india). The fed has been considering increasing interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) announced, on Mar 5, 2015, the beginning on Mar 9, 2015 of its quantitative easing program denominated as Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP), consisting of “combined monthly purchases of EUR 60 bn [billion] in public and private sector securities” (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/liq/html/pspp.en.html). Expectation of increasing interest rates in the US together with euro rates close to zero or negative cause revaluation of the dollar (or devaluation of the euro and of most currencies worldwide). US corporations suffer currency translation losses of their foreign transactions and investments (http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Pronouncement_C/SummaryPage&cid=900000010318) while the US becomes less competitive in world trade (Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c)). The DJIA fell 1.5 percent on Mar 6, 2015 and the dollar revalued 2.2 percent from Mar 5 to Mar 6, 2015. The euro has devalued 42.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Nov 4, 2016.

| Fri 27 Feb | Mon 3/2 | Tue 3/3 | Wed 3/4 | Thu 3/5 | Fri 3/6 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1197 1.6% 0.0% | 1.1185 0.1% 0.1% | 1.1176 0.2% 0.1% | 1.1081 1.0% 0.9% | 1.1030 1.5% 0.5% | 1.0843 3.2% 1.7% |

Chair Yellen explained the removal of the word “patience” from the advanced guidance at the press conference following the FOMC meeting on Mar 18, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20150318.pdf):

“In other words, just because we removed the word “patient” from the statement doesn’t mean we are going to be impatient. Moreover, even after the initial increase in the target funds rate, our policy is likely to remain highly accommodative to support continued progress toward our objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation.”

Exchange rate volatility is increasing in response of “impatience” in financial markets with monetary policy guidance and measures:

| Fri Mar 6 | Mon 9 | Tue 10 | Wed 11 | Thu 12 | Fri 13 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0843 3.2% 1.7% | 1.0853 -0.1% -0.1% | 1.0700 1.3% 1.4% | 1.0548 2.7% 1.4% | 1.0637 1.9% -0.8% | 1.0497 3.2% 1.3% |

| Fri Mar 13 | Mon 16 | Tue 17 | Wed 18 | Thu 19 | Fri 20 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0497 3.2% 1.3% | 1.0570 -0.7% -0.7% | 1.0598 -1.0% -0.3% | 1.0864 -3.5% -2.5% | 1.0661 -1.6% 1.9% | 1.0821 -3.1% -1.5% |

| Fri Apr 24 | Mon 27 | Tue 28 | Wed 29 | Thu 30 | May Fri 1 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0874 -0.6% -0.4% | 1.0891 -0.2% -0.2% | 1.0983 -1.0% -0.8% | 1.1130 -2.4% -1.3% | 1.1223 -3.2% -0.8% | 1.1199 -3.0% 0.2% |

In a speech at Brown University on May 22, 2015, Chair Yellen stated (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150522a.htm):

“For this reason, if the economy continues to improve as I expect, I think it will be appropriate at some point this year to take the initial step to raise the federal funds rate target and begin the process of normalizing monetary policy. To support taking this step, however, I will need to see continued improvement in labor market conditions, and I will need to be reasonably confident that inflation will move back to 2 percent over the medium term. After we begin raising the federal funds rate, I anticipate that the pace of normalization is likely to be gradual. The various headwinds that are still restraining the economy, as I said, will likely take some time to fully abate, and the pace of that improvement is highly uncertain.”

The US dollar appreciated 3.8 percent relative to the euro in the week of May 22, 2015:

| Fri May 15 | Mon 18 | Tue 19 | Wed 20 | Thu 21 | Fri 22 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1449 -2.2% -0.3% | 1.1317 1.2% 1.2% | 1.1150 2.6% 1.5% | 1.1096 3.1% 0.5% | 1.1113 2.9% -0.2% | 1.1015 3.8% 0.9% |

The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, warned on Jun 4, 2015, that: (http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2015/06/04/u-s-economy-returning-to-growth-but-pockets-of-vulnerability/):

“The Fed’s first rate increase in almost 9 years is being carefully prepared and telegraphed. Nevertheless, regardless of the timing, higher US policy rates could still result in significant market volatility with financial stability consequences that go well beyond US borders. I weighing these risks, we think there is a case for waiting to raise rates until there are more tangible signs of wage or price inflation than are currently evident. Even after the first rate increase, a gradual rise in the federal fund rates will likely be appropriate.”

The President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, warned on Jun 3, 2015 that (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2015/html/is150603.en.html):

“But certainly one lesson is that we should get used to periods of higher volatility. At very low levels of interest rates, asset prices tend to show higher volatility…the Governing Council was unanimous in its assessment that we should look through these developments and maintain a steady monetary policy stance.”

The Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Janet L. Yellen, stated on Jul 10, 2015 that (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150710a.htm):

“Based on my outlook, I expect that it will be appropriate at some point later this year to take the first step to raise the federal funds rate and thus begin normalizing monetary policy. But I want to emphasize that the course of the economy and inflation remains highly uncertain, and unanticipated developments could delay or accelerate this first step. I currently anticipate that the appropriate pace of normalization will be gradual, and that monetary policy will need to be highly supportive of economic activity for quite some time. The projections of most of my FOMC colleagues indicate that they have similar expectations for the likely path of the federal funds rate. But, again, both the course of the economy and inflation are uncertain. If progress toward our employment and inflation goals is more rapid than expected, it may be appropriate to remove monetary policy accommodation more quickly. However, if progress toward our goals is slower than anticipated, then the Committee may move more slowly in normalizing policy.”

There is essentially the same view in the Testimony of Chair Yellen in delivering the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress on Jul 15, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20150715a.htm).

At the press conference after the meeting of the FOMC on Sep 17, 2015, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20150917.pdf 4):

“The outlook abroad appears to have become more uncertain of late, and heightened concerns about growth in China and other emerging market economies have led to notable volatility in financial markets. Developments since our July meeting, including the drop in equity prices, the further appreciation of the dollar, and a widening in risk spreads, have tightened overall financial conditions to some extent. These developments may restrain U.S. economic activity somewhat and are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation in the near term. Given the significant economic and financial interconnections between the United States and the rest of the world, the situation abroad bears close watching.”

Some equity markets fell on Fri Sep 18, 2015:

| Fri Sep 11 | Mon 14 | Tue 15 | Wed 16 | Thu 17 | Fri 18 |

| DJIA 16433.09 2.1% 0.6% | 16370.96 -0.4% -0.4% | 16599.85 1.0% 1.4% | 16739.95 1.9% 0.8% | 16674.74 1.5% -0.4% | 16384.58 -0.3% -1.7% |

| Nikkei 225 18264.22 2.7% -0.2% | 17965.70 -1.6% -1.6% | 18026.48 -1.3% 0.3% | 18171.60 -0.5% 0.8% | 18432.27 0.9% 1.4% | 18070.21 -1.1% -2.0% |

| DAX 10123.56 0.9% -0.9% | 10131.74 0.1% 0.1% | 10188.13 0.6% 0.6% | 10227.21 1.0% 0.4% | 10229.58 1.0% 0.0% | 9916.16 -2.0% -3.1% |

Frank H. Knight (1963, 233), in Risk, uncertainty and profit, distinguishes between measurable risk and unmeasurable uncertainty. Chair Yellen, in a lecture on “Inflation dynamics and monetary policy,” on Sep 24, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150924a.htm), states that (emphasis added):

· “The economic outlook, of course, is highly uncertain”

· “Considerable uncertainties also surround the outlook for economic activity”

· “Given the highly uncertain nature of the outlook…”

Is there a “science” or even “art” of central banking under this extreme uncertainty in which policy does not generate higher volatility of money, income, prices and values of financial assets?

Lingling Wei, writing on Oct 23, 2015, on China’s central bank moves to spur economic growth,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-central-bank-cuts-rates-1445601495), analyzes the reduction by the People’s Bank of China (http://www.pbc.gov.cn/ http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130437/index.html) of borrowing and lending rates of banks by 50 basis points and reserve requirements of banks by 50 basis points. Paul Vigna, writing on Oct 23, 2015, on “Stocks rally out of correction territory on latest central bank boost,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2015/10/23/stocks-rally-out-of-correction-territory-on-latest-central-bank-boost/), analyzes the rally in financial markets following the statement on Oct 22, 2015, by the President of the European Central Bank (ECB) Mario Draghi of consideration of new quantitative measures in Dec 2015 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0814riKW25k&rel=0) and the reduction of bank lending/deposit rates and reserve requirements of banks by the People’s Bank of China on Oct 23, 2015. The dollar revalued 2.8 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23, 2015, following the intended easing of the European Central Bank. The DJIA rose 2.8 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23 and the DAX index of German equities rose 5.4 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23, 2015.

| Fri Oct 16 | Mon 19 | Tue 20 | Wed 21 | Thu 22 | Fri 23 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1350 0.1% 0.3% | 1.1327 0.2% 0.2% | 1.1348 0.0% -0.2% | 1.1340 0.1% 0.1% | 1.1110 2.1% 2.0% | 1.1018 2.9% 0.8% |

| DJIA 17215.97 0.8% 0.4% | 17230.54 0.1% 0.1% | 17217.11 0.0% -0.1% | 17168.61 -0.3% -0.3% | 17489.16 1.6% 1.9% | 17646.70 2.5% 0.9% |

| Dow Global 2421.58 0.3% 0.6% | 2414.33 -0.3% -0.3% | 2411.03 -0.4% -0.1% | 2411.27 -0.4% 0.0% | 2434.79 0.5% 1.0% | 2458.13 1.5% 1.0% |

| DJ Asia Pacific 1402.31 1.1% 0.3% | 1398.80 -0.3% -0.3% | 1395.06 -0.5% -0.3% | 1402.68 0.0% 0.5% | 1396.03 -0.4% -0.5% | 1415.50 0.9% 1.4% |

| Nikkei 225 18291.80 -0.8% 1.1% | 18131.23 -0.9% -0.9% | 18207.15 -0.5% 0.4% | 18554.28 1.4% 1.9% | 18435.87 0.8% -0.6% | 18825.30 2.9% 2.1% |

| Shanghai 3391.35 6.5% 1.6% | 3386.70 -0.1% -0.1% | 3425.33 1.0% 1.1% | 3320.68 -2.1% -3.1% | 3368.74 -0.7% 1.4% | 3412.43 0.6% 1.3% |

| DAX 10104.43 0.1% 0.4% | 10164.31 0.6% 0.6% | 10147.68 0.4% -0.2% | 10238.10 1.3% 0.9% | 10491.97 3.8% 2.5% | 10794.54 6.8% 2.9% |

Ben Leubsdorf, writing on “Fed’s Yellen: December is “Live Possibility” for First Rate Increase,” on Nov 4, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-yellen-december-is-live-possibility-for-first-rate-increase-1446654282) quotes Chair Yellen that a rate increase in “December would be a live possibility.” The remark of Chair Yellen was during a hearing on supervision and regulation before the Committee on Financial Services, US House of Representatives (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20151104a.htm) and a day before the release of the employment situation report for Oct 2015 (Section I). The dollar revalued 2.4 percent during the week. The euro has devalued 42.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Nov 4, 2016.

| Fri Oct 30 | Mon 2 | Tue 3 | Wed 4 | Thu 5 | Fri 6 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1007 0.1% -0.3% | 1.1016 -0.1% -0.1% | 1.0965 0.4% 0.5% | 1.0867 1.3% 0.9% | 1.0884 1.1% -0.2% | 1.0742 2.4% 1.3% |

The release on Nov 18, 2015 of the minutes of the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) meeting held on Oct 28, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20151028.htm) states:

“Most participants anticipated that, based on their assessment of the current economic situation and their outlook for economic activity, the labor market, and inflation, these conditions [for interest rate increase] could well be met by the time of the next meeting. Nonetheless, they emphasized that the actual decision would depend on the implications for the medium-term economic outlook of the data received over the upcoming intermeeting period… It was noted that beginning the normalization process relatively soon would make it more likely that the policy trajectory after liftoff could be shallow.”

Markets could have interpreted a symbolic increase in the fed funds rate at the meeting of the FOMC on Dec 15-16, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm) followed by “shallow” increases, explaining the sharp increase in stock market values and appreciation of the dollar after the release of the minutes on Nov 18, 2015:

| Fri Nov 13 | Mon 16 | Tue 17 | Wed 18 | Thu 19 | Fri 20 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0774 -0.3% 0.4% | 1.0686 0.8% 0.8% | 1.0644 1.2% 0.4% | 1.0660 1.1% -0.2% | 1.0735 0.4% -0.7% | 1.0647 1.2% 0.8% |

| DJIA 17245.24 -3.7% -1.2% | 17483.01 1.4% 1.4% | 17489.50 1.4% 0.0% | 17737.16 2.9% 1.4% | 17732.75 2.8% 0.0% | 17823.81 3.4% 0.5% |

| DAX 10708.40 -2.5% -0.7% | 10713.23 0.0% 0.0% | 10971.04 2.5% 2.4% | 10959.95 2.3% -0.1% | 11085.44 3.5% 1.1% | 11119.83 3.8% 0.3% |

In testimony before The Joint Economic Committee of Congress on Dec 3, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20151203a.htm), Chair Yellen reiterated that the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) “anticipates that even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic condition may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below the Committee views as normal in the longer run.” Todd Buell and Katy Burne, writing on “Draghi says ECB could step up stimulus efforts if necessary,” on Dec 4, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/draghi-says-ecb-could-step-up-stimulus-efforts-if-necessary-1449252934), analyze that the President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, reassured financial markets that the ECB will increase stimulus if required to raise inflation the euro area to targets. The USD depreciated 3.1 percent on Thu Dec 3, 2015 after weaker than expected measures by the European Central Bank. DJIA fell 1.4 percent on Dec 3 and increased 2.1 percent on Dec 4. DAX fell 3.6 percent on Dec 3.

| Fri Nov 27 | Mon 30 | Tue 1 | Wed 2 | Thu 3 | Fri 4 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0594 0.5% 0.2% | 1.0565 0.3% 0.3% | 1.0634 -0.4% -0.7% | 1.0616 -0.2% 0.2% | 1.0941 -3.3% -3.1% | 1.0885 -2.7% 0.5% |

| DJIA 17798.49 -0.1% -0.1% | 17719.92 -0.4% -0.4% | 17888.35 0.5% 1.0% | 17729.68 -0.4% -0.9% | 17477.67 -1.8% -1.4% | 17847.63 0.3% 2.1% |

| DAX 11293.76 1.6% -0.2% | 11382.23 0.8% 0.8% | 11261.24 -0.3% -1.1% | 11190.02 -0.9% -0.6% | 10789.24 -4.5% -3.6% | 10752.10 -4.8% -0.3% |

At the press conference following the meeting of the FOMC on Dec 16, 2015, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20151216.pdf page 8):

“And we recognize that monetary policy operates with lags. We would like to be able to move in a prudent, and as we've emphasized, gradual manner. It's been a long time since the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates, and I think it's prudent to be able to watch what the impact is on financial conditions and spending in the economy and moving in a timely fashion enables us to do this.”

The implication of this statement is that the state of the art is not accurate in analyzing the effects of monetary policy on financial markets and economic activity. The US dollar appreciated and equities fluctuated:

| Fri Dec 11 | Mon 14 | Tue 15 | Wed 16 | Thu 17 | Fri 18 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0991 -1.0% -0.4% | 1.0993 0.0% 0.0% | 1.0932 0.5% 0.6% | 1.0913 0.7% 0.2% | 1.0827 1.5% 0.8% | 1.0868 1.1% -0.4% |

| DJIA 17265.21 -3.3% -1.8% | 17368.50 0.6% 0.6% | 17524.91 1.5% 0.9% | 17749.09 2.8% 1.3% | 17495.84 1.3% -1.4% | 17128.55 -0.8% -2.1% |

| DAX 10340.06 -3.8% -2.4% | 10139.34 -1.9% -1.9% | 10450.38 -1.1% 3.1% | 10469.26 1.2% 0.2% | 10738.12 3.8% 2.6% | 10608.19 2.6% -1.2% |

On January 29, 2016, the Policy Board of the Bank of Japan introduced a new policy to attain the “price stability target of 2 percent at the earliest possible time” (https://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2016/k160129a.pdf). The new framework consists of three dimensions: quantity, quality and interest rate. The interest rate dimension consists of rates paid to current accounts that financial institutions hold at the Bank of Japan of three tiers zero, positive and minus 0.1 percent. The quantitative dimension consists of increasing the monetary base at the annual rate of 80 trillion yen. The qualitative dimension consists of purchases by the Bank of Japan of Japanese government bonds (JGBs), exchange traded funds (ETFs) and Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITS). The yen devalued sharply relative to the dollar and world equity markets soared after the new policy announced on Jan 29, 2016:

| Fri 22 | Mon 25 | Tue 26 | Wed 27 | Thu 28 | Fri 29 |

| JPY/ USD 118.77 -1.5% -0.9% | 118.30 0.4% 0.4% | 118.42 0.3% -0.1% | 118.68 0.1% -0.2% | 118.82 0.0% -0.1% | 121.13 -2.0% -1.9% |

| DJIA 16093.51 0.7% 1.3% | 15885.22 -1.3% -1.3% | 16167.23 0.5% 1.8% | 15944.46 -0.9% -1.4% | 16069.64 -0.1% 0.8% | 16466.30 2.3% 2.5% |

| Nikkei 16958.53 -1.1% 5.9% | 17110.91 0.9% 0.9% | 16708.90 -1.5% -2.3% | 17163.92 1.2% 2.7% | 17041.45 0.5% -0.7% | 17518.30 3.3% 2.8% |

| Shanghai 2916.56 0.5% 1.3 | 2938.51 0.8% 0.8% | 2749.79 -5.7% -6.4% | 2735.56 -6.2% -0.5% | 2655.66 -8.9% -2.9% | 2737.60 -6.1% 3.1% |

| DAX 9764.88 2.3% 2.0% | 9736.15 -0.3% -0.3% | 9822.75 0.6% 0.9% | 9880.82 1.2% 0.6% | 9639.59 -1.3% -2.4% | 9798.11 0.3% 1.6% |

In testimony on the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress on Feb 10-11, 2016, Chair Yellen (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20160210a.htm) states: “U.S. real gross domestic product is estimated to have increased about 1-3/4 percent in 2015. Over the course of the year, subdued foreign growth and the appreciation of the dollar restrained net exports. In the fourth quarter of last year, growth in the gross domestic product is reported to have slowed more sharply, to an annual rate of just 3/4 percent; again, growth was held back by weak net exports as well as by a negative contribution from inventory investment.”

Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Yellen Says Fed Should Be Prepared to Use Negative Rates if Needed,” on Feb 11, 2016, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/yellen-reiterates-concerns-about-risks-to-economy-in-senate-testimony-1455203865), analyzes the statement of Chair Yellen in Congress that the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) is considering negative interest rates on bank reserves. The Wall Street Journal provides yields of two and ten-year sovereign bonds with negative interest rates on shorter maturities where central banks pay negative interest rates on excess bank reserves:

| Sovereign Yields 2/12/16 | Japan | Germany | USA |

| 2 Year | -0.168 | -0.498 | 0.694 |

| 10 Year | 0.076 | 0.262 | 1.744 |

On Mar 10, 2016, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced (1) reduction of the refinancing rate by 5 basis points to 0.00 percent; decrease the marginal lending rate to 0.25 percent; reduction of the deposit facility rate to 0,40 percent; increase of the monthly purchase of assets to €80 billion; include nonbank corporate bonds in assets eligible for purchases; and new long-term refinancing operations (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2016/html/pr160310.en.html). The President of the ECB, Mario Draghi, stated in the press conference (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2016/html/is160310.en.html): “How low can we go? Let me say that rates will stay low, very low, for a long period of time, and well past the horizon of our purchases…We don’t anticipate that it will be necessary to reduce rates further. Of course, new facts can change the situation and the outlook.”

The dollar devalued relative to the euro and open stock markets traded lower after the announcement on Mar 10, 2016, but stocks rebounded on Mar 11:

| Fri 4 | Mon 7 | Tue 8 | Wed 9 | Thu10 | Fri 11 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1006 -0.7% -0.4% | 1.1012 -0.1% -0.1% | 1.1013 -0.1% 0.0% | 1.0999 0.1% 0.1% | 1.1182 -1.6% -1.7% | 1.1151 -1.3% 0.3% |

| DJIA 17006.77 2.2% 0.4% | 17073.95 0.4% 0.4% | 16964.10 -0.3% -0.6% | 17000.36 0.0% 0.2% | 16995.13 -0.1% 0.0% | 17213.31 1.2% 1.3% |

| DAX 9824.17 3.3% 0.7% | 9778.93 -0.5% 0.5% | 9692.82 -1.3% -0.9% | 9723.09 -1.0% 0.3% | 9498.15 -3.3% -2.3% | 9831.13 0.1% 3.5% |

At the press conference after the FOMC meeting on Sep 21, 2016, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20160921.pdf ): “However, the economic outlook is inherently uncertain.” In the address to the Jackson Hole symposium on Aug 26, 2016, Chair Yellen states: “I believe the case for an increase in in federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months…And, as ever, the economic outlook is uncertain, and so monetary policy is not on a preset course” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20160826a.htm). In a speech at the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, on Jun 6, 2016 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20160606a.htm), Chair Yellen finds that “there is considerable uncertainty about the economic outlook.” There are fifteen references to this uncertainty in the text of 18 pages double-spaced. In the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress on Jun 21, 2016, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20160621a.htm), “Of course, considerable uncertainty about the economic outlook remains.” Frank H. Knight (1963, 233), in Risk, uncertainty and profit, distinguishes between measurable risk and unmeasurable uncertainty. Is there a “science” or even “art” of central banking under this extreme uncertainty in which policy does not generate higher volatility of money, income, prices and values of financial assets?

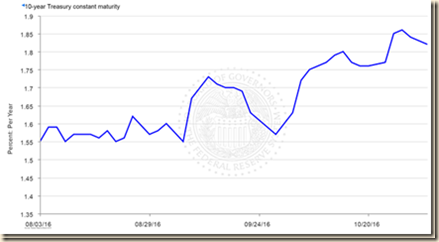

Chart VIII-1, Fed Funds Rate and Yields of Ten-year Treasury Constant Maturity and Baa Seasoned Corporate Bond, Jan 2, 2001 to Oct 6, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chart VIII-1A, Fed Funds Rate and Yield of Ten-year Treasury Constant Maturity, Jan 2, 2001 to Oct 27, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Table VIII-3, Selected Data Points in Chart VIII-1, % per Year

| Fed Funds Overnight Rate | 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity | Seasoned Baa Corporate Bond | |

| 1/2/2001 | 6.67 | 4.92 | 7.91 |

| 10/1/2002 | 1.85 | 3.72 | 7.46 |

| 7/3/2003 | 0.96 | 3.67 | 6.39 |

| 6/22/2004 | 1.00 | 4.72 | 6.77 |

| 6/28/2006 | 5.06 | 5.25 | 6.94 |

| 9/17/2008 | 2.80 | 3.41 | 7.25 |

| 10/26/2008 | 0.09 | 2.16 | 8.00 |

| 10/31/2008 | 0.22 | 4.01 | 9.54 |

| 4/6/2009 | 0.14 | 2.95 | 8.63 |

| 4/5/2010 | 0.20 | 4.01 | 6.44 |

| 2/4/2011 | 0.17 | 3.68 | 6.25 |

| 7/25/2012 | 0.15 | 1.43 | 4.73 |

| 5/1/13 | 0.14 | 1.66 | 4.48 |

| 9/5/13 | 0.089 | 2.98 | 5.53 |

| 11/21/2013 | 0.09 | 2.79 | 5.44 |

| 11/26/13 | 0.09 | 2.74 | 5.34 (11/26/13) |

| 12/5/13 | 0.09 | 2.88 | 5.47 |

| 12/11/13 | 0.09 | 2.89 | 5.42 |

| 12/18/13 | 0.09 | 2.94 | 5.36 |

| 12/26/13 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.37 |

| 1/1/2014 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.34 |

| 1/8/2014 | 0.07 | 2.97 | 5.28 |

| 1/15/2014 | 0.07 | 2.86 | 5.18 |

| 1/22/2014 | 0.07 | 2.79 | 5.11 |

| 1/30/2014 | 0.07 | 2.72 | 5.08 |

| 2/6/2014 | 0.07 | 2.73 | 5.13 |

| 2/13/2014 | 0.06 | 2.73 | 5.12 |

| 2/20/14 | 0.07 | 2.76 | 5.15 |

| 2/27/14 | 0.07 | 2.65 | 5.01 |

| 3/6/14 | 0.08 | 2.74 | 5.11 |

| 3/13/14 | 0.08 | 2.66 | 5.05 |

| 3/20/14 | 0.08 | 2.79 | 5.13 |

| 3/27/14 | 0.08 | 2.69 | 4.95 |

| 4/3/14 | 0.08 | 2.80 | 5.04 |

| 4/10/14 | 0.08 | 2.65 | 4.89 |

| 4/17/14 | 0.09 | 2.73 | 4.89 |

| 4/24/14 | 0.10 | 2.70 | 4.84 |

| 5/1/14 | 0.09 | 2.63 | 4.77 |

| 5/8/14 | 0.08 | 2.61 | 4.79 |

| 5/15/14 | 0.09 | 2.50 | 4.72 |

| 5/22/14 | 0.09 | 2.56 | 4.81 |

| 5/29/14 | 0.09 | 2.45 | 4.69 |

| 6/05/14 | 0.09 | 2.59 | 4.83 |

| 6/12/14 | 0.09 | 2.58 | 4.79 |

| 6/19/14 | 0.10 | 2.64 | 4.83 |

| 6/26/14 | 0.10 | 2.53 | 4.71 |

| 7/2/14 | 0.10 | 2.64 | 4.84 |

| 7/10/14 | 0.09 | 2.55 | 4.75 |

| 7/17/14 | 0.09 | 2.47 | 4.69 |

| 7/24/14 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 4.72 |

| 7/31/14 | 0.08 | 2.58 | 4.75 |

| 8/7/14 | 0.09 | 2.43 | 4.71 |

| 8/14/14 | 0.09 | 2.40 | 4.69 |

| 8/21/14 | 0.09 | 2.41 | 4.69 |

| 8/28/14 | 0.09 | 2.34 | 4.57 |

| 9/04/14 | 0.09 | 2.45 | 4.70 |

| 9/11/14 | 0.09 | 2.54 | 4.79 |

| 9/18/14 | 0.09 | 2.63 | 4.91 |

| 9/25/14 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 4.79 |

| 10/02/14 | 0.09 | 2.44 | 4.76 |

| 10/09/14 | 0.08 | 2.34 | 4.68 |

| 10/16/14 | 0.09 | 2.17 | 4.64 |

| 10/23/14 | 0.09 | 2.29 | 4.71 |

| 11/13/14 | 0.09 | 2.35 | 4.82 |

| 11/20/14 | 0.10 | 2.34 | 4.86 |

| 11/26/14 | 0.10 | 2.24 | 4.73 |

| 12/04/14 | 0.12 | 2.25 | 4.78 |

| 12/11/14 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 4.72 |

| 12/18/14 | 0.13 | 2.22 | 4.78 |

| 12/23/14 | 0.13 | 2.26 | 4.79 |

| 12/30/14 | 0.06 | 2.20 | 4.69 |

| 1/8/15 | 0.12 | 2.03 | 4.57 |

| 1/15/15 | 0.12 | 1.77 | 4.42 |

| 1/22/15 | 0.12 | 1.90 | 4.49 |

| 1/29/15 | 0.11 | 1.77 | 4.35 |

| 2/05/15 | 0.12 | 1.83 | 4.43 |

| 2/12/15 | 0.12 | 1.99 | 4.53 |

| 2/19/15 | 0.12 | 2.11 | 4.64 |

| 2/26/15 | 0.11 | 2.03 | 4.47 |

| 3/5/215 | 0.11 | 2.11 | 4.58 |

| 3/12/15 | 0.11 | 2.10 | 4.56 |

| 3/19/15 | 0.12 | 1.98 | 4.48 |

| 3/26/15 | 0.11 | 2.01 | 4.56 |

| 4/03/15 | 0.12 | 1.92 | 4.47 |

| 4/9/15 | 0.12 | 1.97 | 4.50 |

| 4/16/15 | 0.13 | 1.90 | 4.45 |

| 4/23/15 | 0.13 | 1.96 | 4.50 |

| 5/1/15 | 0.08 | 2.05 | 4.65 |

| 5/7/15 | 0.13 | 2.18 | 4.82 |

| 5/14/15 | 0.13 | 2.23 | 4.97 |

| 5/21/15 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 4.94 |

| 5/28/15 | 0.12 | 2.13 | 4.88 |

| 6/04/15 | 0.13 | 2.31 | 5.03 |

| 6/11/15 | 0.13 | 2.39 | 5.10 |

| 6/18/15 | 0.14 | 2.35 | 5.17 |

| 6/25/15 | 0.13 | 2.40 | 5.20 |

| 7/1/15 | 0.13 | 2.43 | 5.26 |

| 7/9/15 | 0.13 | 2.32 | 5.20 |

| 7/16/15 | 0.14 | 2.36 | 5.24 |

| 7/23/15 | 0.13 | 2.28 | 5.13 |

| 7/30/15 | 0.14 | 2.28 | 5.16 |

| 8/06/15 | 0.14 | 2.23 | 5.15 |

| 8/20/15 | 0.15 | 2.09 | 5.13 |

| 8/27/15 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 5.33 |

| 9/03/15 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 5.35 |

| 9/10/15 | 0.14 | 2.23 | 5.35 |

| 9/17/15 | 0.14 | 2.21 | 5.39 |

| 9/25/15 | 0.14 | 2.13 | 5.29 |

| 10/01/15 | 0.13 | 2.05 | 5.36 |

| 10/08/15 | 0.13 | 2.12 | 5.40 |

| 10/15/15 | 0.13 | 2.04 | 5.33 |

| 10/22/15 | 0.12 | 2.04 | 5.30 |

| 10/29/15 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 5.40 |

| 11/05/15 | 0.12 | 2.26 | 5.44 |

| 11/12/15 | 0.12 | 2.32 | 5.51 |

| 11/19/15 | 0.12 | 2.24 | 5.44 |

| 11/25/15 | 0.12 | 2.23 | 5.44 |

| 12/03/15 | 0.13 | 2.33 | 5.51 |

| 12/10/15 | 0.14 | 2.24 | 5.43 |

| 12/17/15 | 0.37 | 2.24 | 5.45 |

| 12/23/15 | 0.36 | 2.27 | 5.53 |

| 12/30/15 | 0.35 | 2.31 | 5.54 |

| 1/07/2016 | 0.36 | 2.16 | 5.44 |

| 01/14/16 | 0.36 | 2.10 | 5.46 |

| 01/20/16 | 0.37 | 2.01 | 5.41 |

| 01/29/16 | 0.38 | 2.00 | 5.48 |

| 02/04/16 | 0.38 | 1.87 | 5.40 |

| 02/11/16 | 0.38 | 1.63 | 5.26 |

| 02/18/16 | 0.38 | 1.75 | 5.37 |

| 02/25/16 | 0.37 | 1.71 | 5.27 |

| 03/03/16 | 0.37 | 1.83 | 5.30 |

| 03/10/16 | 0.36 | 1.93 | 5.23 |

| 03/17/16 | 0.37 | 1.91 | 5.11 |

| 03/24/16 | 0.37 | 1.91 | 4.97 |

| 03/31/16 | 0.25 | 1.78 | 4.90 |

| 04/07/16 | 0.37 | 1.70 | 4.76 |

| 04/14/16 | 0.37 | 1.80 | 4.79 |

| 04/21/16 | 0.37 | 1.88 | 4.79 |

| 04/28/16 | 0.37 | 1.84 | 4.73 |

| 05/05/16 | 0.37 | 1.76 | 4.62 |

| 05/12/16 | 0.37 | 1.75 | 4.66 |

| 05/19/16 | 0.37 | 1.85 | 4.70 |

| 05/26/16 | 0.37 | 1.83 | 4.69 |

| 06/02/16 | 0.37 | 1.81 | 4.64 |

| 06/09/16 | 0.37 | 1.68 | 4.53 |

| 06/16/16 | 0.38 | 1.57 | 4.47 |

| 06/23/16 | 0.39 | 1.74 | 4.60 |

| 06/30/16 | 0.36 | 1.49 | 4.41 |

| 07/07/16 | 0.40 | 1.40 | 4.19 |

| 07/14/16 | 0.40 | 1.53 | 4.23 |

| 07/21/16 | 0.40 | 1.57 | 4.25 |

| 07/28/16 | 0.40 | 1.52 | 4.20 |

| 08/04/16 | 0.40 | 1.51 | 4.27 |

| 08/11/16 | 0.40 | 1.57 | 4.27 |

| 08/18/16 | 0.40 | 1.53 | 4.23 |

| 08/25/16 | 0.40 | 1.58 | 4.21 |

| 09/01/16 | 0.40 | 1.57 | 4.19 |

| 09/08/16 | 0.40 | 1.61 | 4.28 |

| 09/15/16 | 0.40 | 1.71 | 4.43 |

| 09/22/16 | 0.40 | 1.63 | 4.32 |

| 09/29/16 | 0.40 | 1.56 | 4.23 |

| 10/06/16 | 0.40 | 1.75 | 4.36 |

| 10/13/16 | 0.40 | 1.75 | NA* |

| 10/20/16 | 0.41 | 1.76 | NA* |

| 10/27/16 | 0.41 | 1.85 | NA* |

| 11/03/16 | 0.41 | 1.82 | NA* |

*Note: the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System discontinued the publication of the BAA bond yield.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

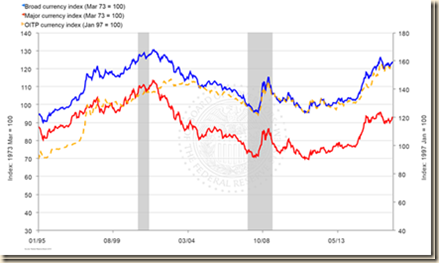

Chart VIII-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate of US dollars (USD) per euro (EUR), USD/EUR. The rate appreciated from USD 1.1066/EUR on Oct 28, 2015 to USD 1.0934/EUR on Oct 28, 2016 or 1.2 percent. The euro has devalued 42.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Nov 4, 2016. US corporations with foreign transactions and net worth experience losses in their balance sheets in converting revenues from depreciated currencies to the dollar. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $123.0 billion in IQ2015 and increased at $70.5 billion in IIQ2015. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $33.1 billion in IIIQ2015. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $17.0 billion in IIIQ2015. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $127.9 billion in IVQ2015 and increased at $66.0 billion in IQ2016. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA fell at $12.5 billion in IIQ2016. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA decreased at $3.3 billion in IIIQ2015. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA fell at $172.7 billion in IVQ2015 and increased at $113.4 billion in IQ2016. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA fell at $28.9 billion in IIQ2016. There is increase in corporate profits from devaluing the dollar with unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and decrease of corporate profits in revaluing the dollar with attempts at “normalization” or increases in interest rates. Conflicts arise while other central banks differ in their adjustment process. The current account deficit seasonally adjusted increases from 2.3 percent of GDP in IVQ2014 to 2.7 percent in IQ2015. The current account deficit increases to 2.7 percent of GDP in IQ2015 and decreases to 2.5 percent of GDP in IIQ2015. The deficit increases to 2.9 percent of GDP in IIIQ2015, easing to 2.8 percent of GDP in IVQ2015. The net international investment position decreases from minus $7.0 trillion in IVQ2014 to minus $6.8 trillion in IQ2015, decreasing at minus $6.7 trillion in IIQ2015. The net international investment position increases to minus $7.6 trillion in IQ2016 and increases to minus $8.0 trillion in IIQ2016. The BEA explains as follows (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/2016/pdf/intinv216.pdf):

The U.S. net international investment position at the end of the second quarter of 2016 was -$8,042.8 billion (preliminary), according to statistics released today by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The net investment position at the end of the first quarter was -$7,582.0 billion (revised). The net investment position decreased $460.8 billion or 6.1 percent in the second quarter, compared with a decrease of 4.1 percent in the first quarter, and an average quarterly decrease of 6.1 percent from the first quarter of 2011 through the fourth quarter of 2015. The $460.8 billion decrease in the net position reflected a $479.9 billion decrease in the net position excluding financial derivatives that was partly offset by a $19.1 billion increase in the net position in financial derivatives.”

The BEA explains further (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/2016/pdf/intinv216.pdf): “U.S. assets increased $404.1 billion to $24,465.9 billion at the end of the second quarter, reflecting increases in both financial derivatives and assets excluding financial derivatives. Financial derivatives with a positive fair value increased $241.4 billion to $3,223.7 billion, mostly in single-currency interest rate contracts. Assets excluding financial derivatives increased $162.7 billion to $21,242.1 billion, reflecting increases in other investment, portfolio investment, and reserve assets that were partly offset by a decrease in direct investment. Increases resulting from financial transactions were partly offset by depreciation of major foreign currencies against the U.S. dollar that lowered the value of U.S. assets in dollar terms.”

Chart VIII-2, Exchange Rate of US Dollars (USD) per Euro (EUR), Oct 28, 2015 to Oct 28, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H10/default.htm

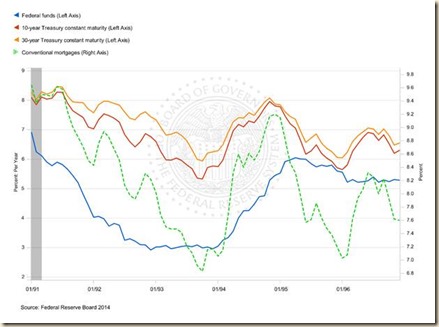

Chart VIII-3 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the yield of the 10-year Treasury constant maturity note from 1.52 percent on Aug 3, 2016 to 1.82 percent on Nov 3, 2016. There is turbulence in financial markets originating in a combination of intentions of normalizing or increasing US policy fed funds rate, quantitative easing in Europe and Japan and increasing perception of financial/economic risks.

Chart VIII-3, Yield of Ten-year Constant Maturity Treasury, Aug 3, 2016 to Nov 3, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chart S provides the yield of the two-year Treasury constant maturity from Mar 17, 2014, two days before the guidance of Chair Yellen on Mar 19, 2014, to Nov 3, 2016. Chart SA provides the yields of the seven-, ten- and thirty-year Treasury constant maturity in the same dates. Yields increased right after the guidance of Chair Yellen. The two-year yield remain at a higher level than before while the ten-year yield fell and increased again. There could be more immediate impact on two-year yields of an increase in the fed funds rates but the effects would spread throughout the term structure of interest rates (Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1981, 1985, Ingersoll 1987). Yields converged toward slightly lower earlier levels in the week of Apr 24, 2014 with reallocation of portfolios of risk financial assets away from equities and into bonds and commodities. There is ongoing reshuffling of portfolios to hedge against geopolitical events and world/regional economic performance.

Chart S, US, Yield of Two-Year Treasury Constant Maturity, Mar 17, 2014 to Nov 3, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chart SA, US, Yield of Seven-Year, Ten-Year and Thirty-Year Treasury Constant Maturity, Mar 17, 2014 to Nov 3, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20140331a.htm):

“And based on the evidence available, it is clear to me that the U.S. economy is still considerably short of the two goals assigned to the Federal Reserve by the Congress. The first of those goals is maximum sustainable employment, the highest level of employment that can be sustained while maintaining a stable inflation rate. Most of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee and I estimate that the unemployment rate consistent with maximum sustainable employment is now between 5.2 percent and 5.6 percent, well below the 6.7 percent rate in February.

Let me explain what I mean by that word "slack" and why it is so important.

Slack means that there are significantly more people willing and capable of filling a job than there are jobs for them to fill. During a period of little or no slack, there still may be vacant jobs and people who want to work, but a large share of those willing to work lack the skills or are otherwise not well suited for the jobs that are available. With 6.7 percent unemployment, it might seem that there must be a lot of slack in the U.S. economy, but there are reasons why that may not be true.”

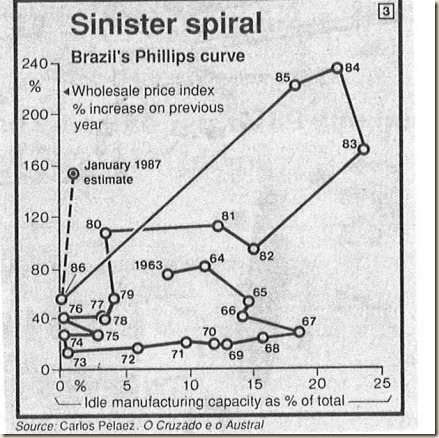

Inflation and unemployment in the period 1966 to 1985 is analyzed by Cochrane (2011Jan, 23) by means of a Phillips circuit joining points of inflation and unemployment. Chart VI-1B for Brazil in Pelaez (1986, 94-5) was reprinted in The Economist in the issue of Jan 17-23, 1987 as updated by the author. Cochrane (2011Jan, 23) argues that the Phillips circuit shows the weakness in Phillips curve correlation. The explanation is by a shift in aggregate supply, rise in inflation expectations or loss of anchoring. The case of Brazil in Chart VI-1B cannot be explained without taking into account the increase in the fed funds rate that reached 22.36 percent on Jul 22, 1981 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm) in the Volcker Fed that precipitated the stress on a foreign debt bloated by financing balance of payments deficits with bank loans in the 1970s. The loans were used in projects, many of state-owned enterprises with low present value in long gestation. The combination of the insolvency of the country because of debt higher than its ability of repayment and the huge government deficit with declining revenue as the economy contracted caused adverse expectations on inflation and the economy. This interpretation is consistent with the case of the 24 emerging market economies analyzed by Reinhart and Rogoff (2010GTD, 4), concluding that “higher debt levels are associated with significantly higher levels of inflation in emerging markets. Median inflation more than doubles (from less than seven percent to 16 percent) as debt rises from the low (0 to 30 percent) range to above 90 percent. Fiscal dominance is a plausible interpretation of this pattern.”

The reading of the Phillips circuits of the 1970s by Cochrane (2011Jan, 25) is doubtful about the output gap and inflation expectations:

“So, inflation is caused by ‘tightness’ and deflation by ‘slack’ in the economy. This is not just a cause and forecasting variable, it is the cause, because given ‘slack’ we apparently do not have to worry about inflation from other sources, notwithstanding the weak correlation of [Phillips circuits]. These statements [by the Fed] do mention ‘stable inflation expectations. How does the Fed know expectations are ‘stable’ and would not come unglued once people look at deficit numbers? As I read Fed statements, almost all confidence in ‘stable’ or ‘anchored’ expectations comes from the fact that we have experienced a long period of low inflation (adaptive expectations). All these analyses ignore the stagflation experience in the 1970s, in which inflation was high even with ‘slack’ markets and little ‘demand, and ‘expectations’ moved quickly. They ignore the experience of hyperinflations and currency collapses, which happen in economies well below potential.”

Yellen (2014Aug22) states that “Historically, slack has accounted for only a small portion of the fluctuations in inflation. Indeed, unusual aspects of the current recovery may have shifted the lead-lag relationship between a tightening labor market and rising inflation pressures in either direction.”

Chart VI-1B provides the tortuous Phillips Circuit of Brazil from 1963 to 1987. There were no reliable consumer price index and unemployment data in Brazil for that period. Chart VI-1B used the more reliable indicator of inflation, the wholesale price index, and idle capacity of manufacturing as a proxy of unemployment in large urban centers.

ChVI1-B, Brazil, Phillips Circuit, 1963-1987

Source:

©Carlos Manuel Pelaez, O Cruzado e o Austral: Análise das Reformas Monetárias do Brasil e da Argentina. São Paulo: Editora Atlas, 1986, pages 94-5. Reprinted in: Brazil. Tomorrow’s Italy, The Economist, 17-23 January 1987, page 25.

The minutes of the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on Sep 16-17, 2014, reveal concern with global economic conditions (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20140917.htm):

“Most viewed the risks to the outlook for economic activity and the labor market as broadly balanced. However, a number of participants noted that economic growth over the medium term might be slower than they expected if foreign economic growth came in weaker than anticipated, structural productivity continued to increase only slowly, or the recovery in residential construction continued to lag.”

There is similar concern in the minutes of the meeting of the FOMC on Dec 16-17, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20141217.htm):

“In their discussion of the foreign economic outlook, participants noted that the implications of the drop in crude oil prices would differ across regions, especially if the price declines affected inflation expectations and financial markets; a few participants said that the effect on overseas employment and output as a whole was likely to be positive. While some participants had lowered their assessments of the prospects for global economic growth, several noted that the likelihood of further responses by policymakers abroad had increased. Several participants indicated that they expected slower economic growth abroad to negatively affect the U.S. economy, principally through lower net exports, but the net effect of lower oil prices on U.S. economic activity was anticipated to be positive.”

There is concern at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) with the world economy and financial markets (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20160127a.htm): “The Committee is closely monitoring global economic and financial developments and is assessing their implications for the labor market and inflation, and for the balance of risks to the outlook” (emphasis added). This concern should include the effects on dollar revaluation of competitive easing by other central banks such as quantitative and qualitative easing with negative nominal interest rates.”

It is quite difficult to measure inflationary expectations because they tend to break abruptly from past inflation. There could still be an influence of past and current inflation in the calculation of future inflation by economic agents. Table VIII-1 provides inflation of the CPI. In the three months from Jul 2016 to Sep 2016, CPI inflation for all items seasonally adjusted was 2.0 percent in annual equivalent, obtained by calculating accumulated inflation from Jul 2016 to Sep 2016 and compounding for a full year. In the 12 months ending in Sep 2016, CPI inflation of all items not seasonally adjusted was 1.5 percent. Inflation in Sep 2016 seasonally adjusted was 0.3 percent relative to Aug 2016, or 3.7 percent annual equivalent (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/). The second row provides the same measurements for the CPI of all items excluding food and energy: 2.2 percent in 12 months, 2.0 percent in annual equivalent Jul 2016-Sep 2016 and 0.1 percent in Sep 2016 or 1.2 percent in annual equivalent. The Wall Street Journal provides the yield curve of US Treasury securities (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/mdc_bonds.html?mod=mdc_topnav_2_3000). The shortest term is 0.246 percent for one month, 0.366 percent for three months, 0.511 percent for six months, 0.609 percent for one year, 0.794 percent for two years, 0.938 percent for three years, 1.235 percent for five years, 1.542 percent for seven years, 1.776 percent for ten years and 2.562 percent for 30 years. The Irving Fisher (1930) definition of real interest rates is approximately the difference between nominal interest rates, which are those estimated by the Wall Street Journal, and the rate of inflation expected in the term of the security, which could behave as in Table VIII-1. Inflation in Jan 2016 is low in 12 months because of the unwinding of carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures prices but could ignite again with subdued risk aversion. Real interest rates in the US have been negative during substantial periods in the past decade while monetary policy pursues a policy of attaining its “dual mandate” of (http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm):

“Conducting the nation's monetary policy by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”

Negative real rates of interest distort calculations of risk and returns from capital budgeting by firms, through lending by financial intermediaries to decisions on savings, housing and purchases of households. Inflation on near zero interest rates misallocates resources away from their most productive uses and creates uncertainty of the future path of adjustment to higher interest rates that inhibit sound decisions.

Table VIII-1, US, Consumer Price Index Percentage Changes 12 months NSA and Annual Equivalent ∆%

| % RI | ∆% 12 Months Sep 2016/Sep | ∆% Annual Equivalent Jul 2016 to Sep 2016 SA | ∆% Sep 2016/Aug 2016 SA | |

| CPI All Items | 100.000 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 79.183 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.1 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Professionals use a variety of techniques in measuring interest rate risk (Fabozzi, Buestow and Johnson, 2006, Chapter Nine, 183-226):

- Full valuation approach in which securities and portfolios are shocked by 50, 100, 200 and 300 basis points to measure their impact on asset values

- Stress tests requiring more complex analysis and translation of possible events with high impact even if with low probability of occurrence into effects on actual positions and capital

- Value at Risk (VaR) analysis of maximum losses that are likely in a time horizon

- Duration and convexity that are short-hand convenient measurement of changes in prices resulting from changes in yield captured by duration and convexity

- Yield volatility

Analysis of these methods is in Pelaez and Pelaez (International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-162) and Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. (I) (2008a), 78-100). Frederick R. Macaulay (1938) introduced the concept of duration in contrast with maturity for analyzing bonds. Duration is the sensitivity of bond prices to changes in yields. In economic jargon, duration is the yield elasticity of bond price to changes in yield, or the percentage change in price after a percentage change in yield, typically expressed as the change in price resulting from change of 100 basis points in yield. The mathematical formula is the negative of the yield elasticity of the bond price or –[dB/d(1+y)]((1+y)/B), where d is the derivative operator of calculus, B the bond price, y the yield and the elasticity does not have dimension (Hallerbach 2001). The duration trap of unconventional monetary policy is that duration is higher the lower the coupon and higher the lower the yield, other things being constant. Coupons and yields are historically low because of unconventional monetary policy. Duration dumping during a rate increase may trigger the same crossfire selling of high duration positions that magnified the credit crisis. Traders reduced positions because capital losses in one segment, such as mortgage-backed securities, triggered haircuts and margin increases that reduced capital available for positioning in all segments, causing fire sales in multiple segments (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2008b), 217-24). Financial markets are currently experiencing fear of duration and riskier asset classes resulting from the debate within and outside the Fed on tapering quantitative easing. Table VIII-2 provides the yield curve of Treasury securities on Nov 4, 2016, Dec 31, 2013, May 1, 2013, Nov 4, 2015 and Nov 3, 2006. There is oscillating steepening of the yield curve for longer maturities, which are also the ones with highest duration. The 10-year yield increased from 1.45 percent on Jul 26, 2012 to 3.04 percent on Dec 31, 2013 and 1.86 percent on Oct 28, 2016, as measured by the United States Treasury. Assume that a bond with maturity in 10 years were issued on Dec 31, 2013, at par or price of 100 with coupon of 1.45 percent. The price of that bond would be 86.3778 with instantaneous increase of the yield to 3.04 percent for loss of 13.6 percent and far more with leverage. Assume that the yield of a bond with exactly ten years to maturity and coupon of 1.79 percent would jump instantaneously from yield of 1.79 percent on Nov 4, 2016 to 4.72 percent as occurred on Nov 3, 2006 when the economy was closer to full employment. The price of the hypothetical bond issued with coupon of 1.79 percent would drop from 100 to 76.8569 after an instantaneous increase of the yield to 4.72 percent. The price loss would be 23.1 percent. Losses absorb capital available for positioning, triggering crossfire sales in multiple asset classes (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009). What is the path of adjustment of zero interest rates on fed funds and artificially low bond yields? There is no painless exit from unconventional monetary policy. Chris Dieterich, writing on “Bond investors turn to cash,” on Jul 25, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323971204578625900935618178.html), uses data of the Investment Company Institute (http://www.ici.org/) in showing withdrawals of $43 billion in taxable mutual funds in Jun, which is the largest in history, with flows into cash investments such as $8.5 billion in the week of Jul 17 into money-market funds.

Table VIII-2, United States, Treasury Yields

| 11/04/16 | 12/31/13 | 5/01/13 | 11/04/15 | 11/03/06 | |

| 1 M | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 5.18 |