Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth, Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment, IMF View, United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities, United States Housing Collapse, Peaking Valuations of Risk Financial Assets, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013

Executive Summary

I Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IB IMF View of World Economy and Finance

IIA United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IIA1 Transmission of Monetary Policy

IIA2 Functions of Banks

IIA3 United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IIA4 Theory and Reality of Economic History and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

IIB United States Housing Collapse

IIB1 United States New House Sales

IIB2 United States House Prices

IIB3 Factors of United States Housing Collapse

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

Executive Summary

ESI Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth. The US is experiencing the first expansion from a recession after World War II without growth, jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html) and hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html), unsustainable government deficit/debt (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html), waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html) and deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates

(http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html) while valuations of risk financial assets approach historical highs. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The expansion since the third quarter of 2009 (IIIQ2009 (Jun)) to the latest available measurement for IQ(2013) has been at the average annual rate of 2.1 percent per quarter. In contrast, Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). As a result, there are 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 18.2 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html).

The economy of the US can be summarized in growth of economic activity or GDP as decelerating from mediocre growth of 2.4 percent on an annual basis in 2010 and 1.8 percent in 2011 to 2.2 percent in 2012. Calculations below show that actual growth is around 1.9 percent per year. This rate is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which has been always recovered after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May). United States real GDP grew at the rate of 3.2 percent between 1929 and 2012 and at 3.2 percent between 1947 and 2012 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html). Growth is not only mediocre but also sharply decelerating to a rhythm that is not consistent with reduction of unemployment and underemployment of 29.6 million people corresponding to 18.2 percent of the effective labor force of the United States (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). In the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013, US real GDP grew at the seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent rates of 0.1 percent in the first quarter of 2011 (IQ2011), 2.5 percent in IIQ2011, 1.3 percent in IIIQ2011, 4.1 percent in IVQ2011, 2.0 percent in IQ2012, 1.3 percent in IIQ2012, revised 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012, 0.4 percent in IVQ2012 and 2.5 percent in IQ2013. The annual equivalent rate of growth of GDP for the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 is 1.9 percent, obtained as follows. Discounting 0.1 percent to one quarter is 0.025 percent {[(1.001)1/4 -1]100 = 0.025}; discounting 2.5 percent to one quarter is 0.62 percent {[(1.025)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 4.1 percent to one quarter is 1.0 {[(1.04)1/4 -1]100; discounting 2.0 percent to one quarter is 0.50 percent {[(1.020)1/4 -1]100); discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 -1]100}; discounting 3.1 percent to one quarter is 0.77 {[(1.031)1/4 -1]100); discounting 0.4 percent to one quarter is 0.1 percent {[(1.004)1/4 – 1]100}; and discounting 2.5 percent to one quarter is 0.62 percent {[(1.025)1/4 -1}100}. Real GDP growth in the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 accumulated to 4.3 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001 x 1.0062) - 1]100 = 4.3%}. This is equivalent to growth from IQ2011 to IVQ2012 obtained by dividing the seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of IQ2013 of $13,750.1 billion by the SAAR of IVQ2010 of $13,181.2 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1 and Table ESI-3 below) and expressing as percentage {[($13,750.1/$13,181.2) - 1]100 = 4.3%}. The growth rate in annual equivalent for the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 is 1.9 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001 x 1.0062)4/9 -1]100 = 1.9%], or {[($13,750.1/$13,181.2)]4/9-1]100 = 1.9%} dividing the SAAR of IVQ2012 by the SAAR of IVQ2010 in Table ESI-3 below, obtaining the average for nine quarters and the annual average for one year of four quarters. Growth in the four quarters of 2012 accumulates to 1.7 percent {[(1.02)1/4(1.013)1/4(1.031)1/4(1.004)1/4 -1]100 = 1.7%}. This is equivalent to dividing the SAAR of $13,665.4 billion for IVQ2012 in Table ESI-3 by the SAAR of $13,441.0 billion in IVQ2011 except for a rounding discrepancy to obtain 1.7 percent {[($13,665.4/$13,441.0) – 1]100 = 1.7%}. The US economy is still close to a standstill especially considering the GDP report in detail.

Characteristics of the four cyclical contractions are provided in Table ESI-1 with the first column showing the number of quarters of contraction; the second column the cumulative percentage contraction; and the final column the average quarterly rate of contraction. There were two contractions from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and from IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 separated by three quarters of expansion. The drop of output combining the declines in these two contractions is 4.8 percent, which is almost equal to the decline of 4.7 percent in the contraction from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.7 percent cumulatively and fell 45.6 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is entirely misleading.

Table ESI-1, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Percentage Contraction and Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate in Cyclical Contractions

| Number of Quarters | Cumulative Percentage Contraction | Average Percentage Rate | |

| IIQ1953 to IIQ1954 | 4 | -2.5 | -0.64 |

| IIIQ1957 to IIQ1958 | 3 | -3.1 | -1.1 |

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 | 2 | -2.2 | -1.1 |

| IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | 4 | -2.6 | -0.67 |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | 6 | -4.7 | -0.80 |

Sources: Business Cycle Reference Dates: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table ESI-2 shows the extraordinary contrast between the mediocre average annual equivalent growth rate of 2.1 percent of the US economy in the fourteen quarters of the current cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2012 and the average of 5.7 percent in the first thirteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986 and 5.3 percent in the first fifteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986. The line “average first four quarters in four expansions” provides the average growth rate of 7.8 with 7.9 percent from IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955, 9.6 percent from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959, 6.1 percent from IIIQ1975 to IIQ1986 and 7.7 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The United States missed this opportunity of high growth in the initial phase of recovery. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). Table ESI-2 provides an average of 7.8 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions while the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 is only 3.2 percent obtained by diving GDP of $13,103.5 billion in IIIQ2010 by GDP of $12,701.0 billion in IIQ2009 {[$13.103.5/$12,701.0 -1]100 = 3.2%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates. As a result, there are 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 18.2 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). BEA data show the US economy in standstill with annual growth of 2.4 percent in 2010 decelerating to 1.8 percent annual growth in 2011, 2.2 percent in 2012 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and cumulative 1.7 percent in the four quarters of 2012 {[(1.02)1/4(1.013)1/4(1.031)1/4(1.004)1/4 – 1]100 = 1.7%} with minor rounding discrepancy using the SSAR of $13,665.4 billion in IVQ2012 relative to the SAAR of $13,441.0 billion in IVQ2011 {[($13665.4/$13441.00-1]100 = 1.7%}. %}. The growth rate in annual equivalent for the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 is 1.9 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001 x 1.0062)4/9 -1]100 = 1.9%], or {[($13,750.1/$13,181.2)]4/9-1]100 = 1.9%} dividing the SAAR of IVQ2012 by the SAAR of IVQ2010 in Table ESI-3 below, obtaining the average for nine quarters and the annual average for one year of four quarters. The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent and at 7.7 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983.

Table ESI-2, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Growth and Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate in Cyclical Expansions

| Number | Cumulative Growth ∆% | Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate | |

| IIIQ 1954 to IQ1957 | 11 | 12.6 | 4.4 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955 | 4 | 7.9 | |

| IIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 5 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 4 | 9.6 | |

| IIQ1975 to IVQ1976 | 8 | 9.5 | 4.6 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 | 4 | 6.1 | |

| IQ1983 to IQ1986 IQ1983 to IIIQ1986 | 13 15 | 19.6 21.3 | 5.7 5.3 |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 4 | 7.7 | |

| Average First Four Quarters in Four Expansions* | 7.8 | ||

| IIIQ2009 to IQ2013 | 15 | 8.3 | 2.1 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIIQ2010 | 3.2 |

*First Four Quarters: 7.9% IIIQ1954-IIQ1955; 9.6% IIIQ1958-IIQ1959; 6.1% IIIQ1975-IIQ1976; 7.7% IQ1983-IVQ1983

Sources: Business Cycle Reference Dates: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

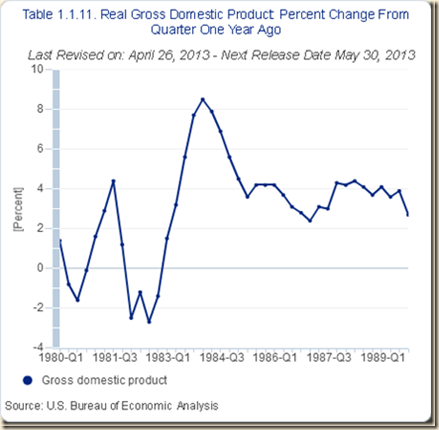

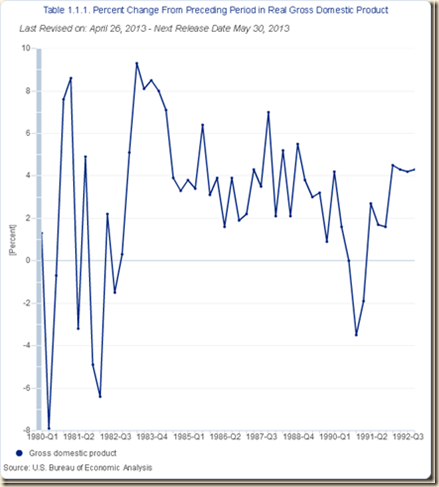

Chart ESI-1 shows US real quarterly GDP growth from 1980 to 1989. The economy contracted during the recession and then expanded vigorously throughout the 1980s, rapidly eliminating the unemployment caused by the contraction.

Chart ESI-1, US, Real GDP, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

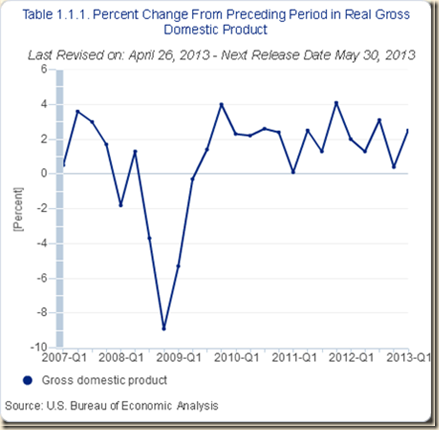

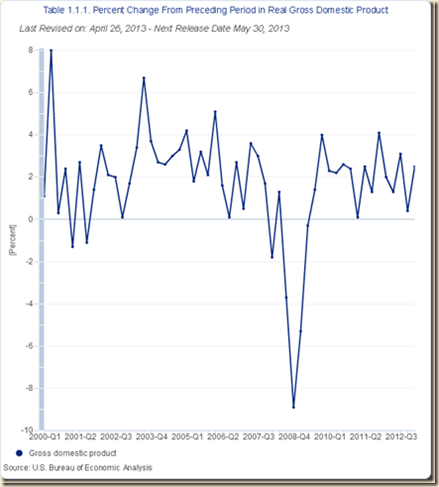

Chart ESI-2 shows the entirely different situation of real quarterly GDP in the US between 2007 and 2012. The economy has underperformed during the first fifteen quarters of expansion for the first time in the comparable contractions since the 1950s. The US economy is now in a perilous standstill.

Chart ESI-2, US, Real GDP, 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

As shown in Tables ESI-1 and ESI-2 above the loss of real GDP in the US during the contraction was 4.7 percent but the gain in the cyclical expansion has been only 8.3 percent (last row in Table I-5), using all latest revisions. As a result, the level of real GDP in IQ2013 with the third estimate and revisions is only higher by 3.2 percent than the level of real GDP in IVQ2007. Table ESI-3 provides in the second column real GDP in billions of chained 2005 dollars. The third column provides the percentage change of the quarter relative to IVQ2007; the fourth column provides the percentage change relative to the prior quarter; and the final fifth column provides the percentage change relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The contraction actually concentrated in two quarters: decline of 2.3 percent in IVQ2008 relative to the prior quarter and decline of 1.3 percent in IQ2009 relative to IVQ2008. The combined fall of GDP in IVQ2008 and IQ2009 was 3.6 percent {[(1-0.023) x (1-0.013) -1]100 = -3.6%}, or {[(IQ2009 $12,711.0)/(IIIQ2008 $13,186.9) – 1]100 = -3.6%}. Those two quarters coincided with the worst effects of the financial crisis. GDP fell 0.1 percent in IIQ2009 but grew 0.4 percent in IIIQ2009, which is the beginning of recovery in the cyclical dates of the NBER. Most of the recovery occurred in five successive quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2010 of growth of 1.0 percent in IVQ2009 and equal growth at 0.6 percent in IQ2010, IIQ2010, IIIQ2010 and IVQ2010 for cumulative growth in those five quarters of 3.4 percent, obtained by accumulating the quarterly rates {[(1.01 x 1.006 x 1.006 x 1.006 x 1.006) – 1]100 = 3.4%} or {[(IVQ2010 $13,181.2)/(IIIQ2009 $12,746.7) – 1]100 = 3.4%}. The economy lost momentum already in 2010 growing at 0.6 percent in each quarter, or annual equivalent 2.4 per cent {[(1.006)4 – 1]100 = 2.4%}, compared with annual equivalent 4.1 percent in IV2009 {[(1.01)4 – 1]100 = 4.1%}. The economy then stalled during the first half of 2011 with growth of 0.0025 percent in IQ2011 and 0.6 percent in IIQ2011 for combined annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent {(1.00025 x 1.006)2}. The economy grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2011 for annual equivalent growth of 1.2 percent in the first three quarters {[(1.00025 x 1.006 x 1.003)4/3 -1]100 = 1.2%}. Growth picked up in IVQ2011 with 1.0 percent relative to IIIQ2011. Growth in a quarter relative to a year earlier in Table I-6 slows from over 2.4 percent during three consecutive quarters from IIQ2010 to IVQ2010 to 1.8 percent in IQ2011, 1.9 percent in IIQ2011, 1.6 percent in IIIQ2011 and 2.0 percent in IVQ2011. As shown below, growth of 1.0 percent in IVQ2011 was partly driven by inventory accumulation. In IQ2012, GDP grew 0.5 percent relative to IVQ2011 and 2.4 percent relative to IQ2011, decelerating to 0.3 percent in IIQ2012 and 2.1 percent relative to IIQ2011 and 0.8 percent in IIIQ2012 and 2.6 percent relative to IIIQ2011 largely because of inventory accumulation and national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.1 percent in IVQ2012 with 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier but mostly because of 1.52 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.28 percentage points of reduction of one-time national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.6 percent in IQ2013 and 1.8 percent relative to IQ2012 in large part because of burning savings to consume caused by financial repression of zero interest rates. Rates of a quarter relative to the prior quarter capture better deceleration of the economy than rates on a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The critical question for which there is not yet definitive solution is whether what lies ahead is continuing growth recession with the economy crawling and unemployment/underemployment at extremely high levels or another contraction or conventional recession. Forecasts of various sources continued to maintain high growth in 2011 without taking into consideration the continuous slowing of the economy in late 2010 and the first half of 2011. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro area is one of the common sources of doubts on the rate and direction of economic growth in the US but there is weak internal demand in the US with almost no investment and spikes of consumption driven by burning saving because of financial repression forever in the form of zero interest rates.

Table ESI-3, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 13,326.0 | NA | NA | 2.2 |

| IQ2008 | 13,266.8 | -0.4 | -0.4 | 1.6 |

| IIQ2008 | 13,310.5 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| IIIQ2008 | 13,186.9 | -1.0 | -0.9 | -0.6 |

| IVQ2008 | 12,883.5 | -3.3 | -2.3 | -3.3 |

| IQ2009 | 12,711.0 | -4.6 | -1.3 | -4.2 |

| IIQ2009 | 12,701.0 | -4.7 | -0.1 | -4.6 |

| IIIQ2009 | 12,746.7 | -4.3 | 0.4 | -3.3 |

| IV2009 | 12,873.1 | -3.4 | 1.0 | -0.1 |

| IQ2010 | 12,947.6 | -2.8 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| IIQ2010 | 13,019.6 | -2.3 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| IIIQ2010 | 13,103.5 | -1.7 | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| IVQ2010 | 13,181.2 | -1.1 | 0.6 | 2.4 |

| IQ2011 | 13,183.8 | -1.1 | 0.0 | 1.8 |

| IIQ2011 | 13,264.7 | -0.5 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| IIIQ2011 | 13,306.9 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| IV2011 | 13,441.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| IQ2012 | 13,506.4 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| IIQ2012 | 13,548.5 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| IIIQ2012 | 13,652.5 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| IVQ2012 | 13,665.4 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| IQ2013 | 13,750.1 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart ESI-3 provides the percentage change of real GDP from the same quarter a year earlier from 1980 to 1989. There were two contractions almost in succession in 1980 and from 1981 to 1983. The expansion was marked by initial high rates of growth as in other recession in the postwar US period during which employment lost in the contraction was recovered. Growth rates continued to be high after the initial phase of expansion.

Chart ESI-3, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The experience of recovery after 2009 is not as complete as during the 1980s. Chart ESI-4 shows the much lower rates of growth in the early phase of the current expansion and how they have sharply declined from an early peak. The US missed the initial high growth rates in cyclical expansions during which unemployment and underemployment are eliminated.

Chart ESI-4, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart ESI-5 provides growth rates from a quarter relative to the prior quarter during the 1980s. There is the same strong initial growth followed by a long period of sustained growth.

Chart ESI-5, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart ESI-6 provides growth rates in a quarter relative to the prior quarter from 2007 to 2012. Growth in the current expansion after IIIQ2009 has not been as strong as in other postwar cyclical expansions.

Chart ESI-6, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

ESII Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment. Table ESII-1 provides real private fixed investment at seasonally adjusted annual rates from IVQ2007 to IQ2013 or for the complete economic cycle. The first column provides the quarter, the second column percentage change relative to IVQ2007, the third column the quarter percentage change in the quarter relative to the prior quarter and the final column percentage change in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. In IQ1980, gross private domestic investment in the US was $778.3 billion of 2005 dollars, growing to $965.9 billion in IVQ1985 or 24.1 percent, as shown in Table IB-2 of IB Collapse of Dynamism of United States Income Growth and Employment Creation (IX Conclusion and extended analysis at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). Gross private domestic investment in the US decreased 6.2 percent from $2,123.6 billion of 2005 dollars in IVQ2007 to $1,991.8 billion in IQ2013. As shown in Table IAI-2, real private fixed investment fell 8.8 percent from $2111.5 billion of 2005 dollars in IVQ2007 to $1925.5 billion in IVQ2012. Growth of real private investment in Table IA1-2 is mediocre for all but four quarters from IIQ2011 to IQ2012.

Table ESII-1, US, Real Private Fixed Investment and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real PFI, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 2111.5 | NA | -1.2 | -1.0 |

| IQ2008 | 2066.4 | -2.1 | -2.1 | -2.9 |

| IIQ2008 | 2039.1 | -3.4 | -1.3 | -5.0 |

| IIIQ2008 | 1973.5 | -6.5 | -3.2 | -7.7 |

| IV2008 | 1835.4 | -13.1 | -7.0 | -13.1 |

| IQ2009 | 1677.3 | -20.6 | -8.6 | -18.8 |

| IIQ2009 | 1593.7 | -24.5 | -5.0 | -21.8 |

| IIIQ2009 | 1581.2 | -25.1 | -0.8 | -19.9 |

| IVQ2009 | 1556.8 | -26.3 | -1.5 | -15.2 |

| IQ2010 | 1553.1 | -26.4 | -0.2 | -7.4 |

| IIQ2010 | 1606.5 | -23.9 | 3.4 | 0.8 |

| IIIQ2010 | 1602.7 | -24.1 | -0.2 | 1.4 |

| IVQ2010 | 1632.3 | -22.7 | 1.8 | 4.8 |

| IQ2011 | 1627.0 | -22.9 | -0.3 | 4.8 |

| IIQ2011 | 1675.4 | -20.7 | 3.0 | 4.3 |

| IIIQ2011 | 1736.8 | -17.7 | 3.7 | 8.4 |

| IVQ2011 | 1778.7 | -15.8 | 2.4 | 9.0 |

| IQ2012 | 1820.6 | -13.8 | 2.4 | 11.9 |

| IIQ2012 | 1840.6 | -12.8 | 1.1 | 9.9 |

| IIIQ2012 | 1844.8 | -12.6 | 0.2 | 6.2 |

| IVQ2012 | 1906.3 | -9.7 | 3.3 | 7.2 |

| IQ2013 | 1925.5 | -8.8 | 1.0 | 5.8 |

PFI: Private Fixed Investment

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

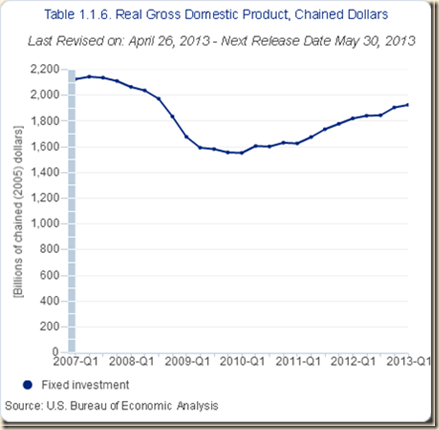

Chart ESII-1 provides real private fixed investment in billions of chained 2005 dollars from IV2007 to IQ2013. Real private fixed investment has not recovered, stabilizing at a level in IQ2013 that is 8.8 percent below the level in IVQ2007.

Chart ESII-1, US, Real Private Fixed Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars, IQ2007 to IQ2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

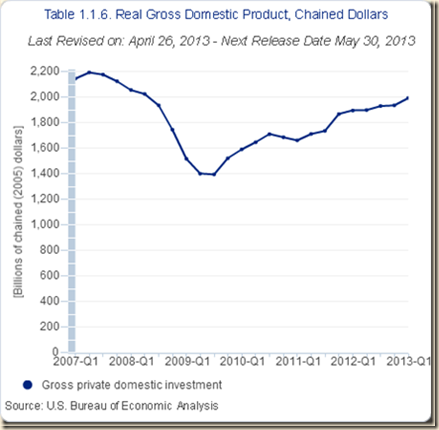

Chart ESII-2 provides real gross private domestic investment in chained dollars of 2005 from 1980 to 1986. Real gross private domestic investment climbed 24.1 percent in IVQ1985 above the level on IQ1980.

Chart ESII-2, US, Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars at Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, 1980-1986

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart ESII-3 provides real gross private domestic investment in the United States in billions of dollars of 2005 from 2006 to 2013. Gross private domestic investment reached a level in IQ2013 that was 8.8 percent lower than the level in IVQ2007.

Chart ESII-3, US, Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars at Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

ESIII United States Housing Collapse. The depressed level of residential construction and new house sales in the US is evident in Table ESIII-1 providing new house sales not seasonally adjusted in Jan-Mar of various years. Sales of new houses in Jan-Mar 2013 are substantially lower than in any year between 1963 and 2013 with the exception of 2009 to 2012. There are only four increases of 19.6 percent relative to Jan-Mar 2012, 46.5 percent relative to Jan-Mar 2011, 20.9 percent relative to Jan-Mar 2010 and 23.8 percent relative to Jan-Mar 2009. Sales of new houses in Jan-Mar 2013 are lower by 26.2 percent relative to Jan-Mar 2008, 51.1 percent relative to 2007, 63.5 percent relative to 2006 and 68.3 percent relative to 2005. The housing boom peaked in 2005 and 2006 when increases in fed funds rates to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006 from 1.0 percent in Jun 2004 affected subprime mortgages that were programmed for refinancing in two or three years on the expectation that price increases forever would raise home equity. Higher home equity would permit refinancing under feasible mortgages incorporating full payment of principal and interest (Gorton 2009EFM; see other references in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html). Sales of new houses in Jan-Mar 2013 relative to the same period in 2004 fell 66.9 percent and 59.4 percent relative to the same period in 2003. Similar percentage declines are also observed for 2013 relative to years from 2000 to 2004. Sales of new houses in Jan-Mar 2013 fell 32.5 per cent relative to the same period in 1995. The population of the US was 179.3 million in 1960 and 281.4 million in 2000 (Hobbs and Stoops 2002, 16). Detailed historical census reports are available from the US Census Bureau at (http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/hiscendata.html). The US population reached 308.7 million in 2010 (http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/). The US population increased by 129.4 million from 1960 to 2010 or 72.2 percent. The final row of Table IIB-3 reveals catastrophic data: sales of new houses in Jan-Mar 2013 of 104 thousand units are lower by 14.0 percent relative to 121 thousand units houses sold in Jan-Mar 1963, the first year when data become available, while population increased 72.2 percent.

Table ESIII-1, US, Sales of New Houses Not Seasonally Adjusted, Thousands and %

| Not Seasonally Adjusted Thousands | |

| Jan-Mar 2013 | 104 |

| Jan-Mar 2012 | 87 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2012 | 19.6* |

| Jan-Mar 2011 | 71 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2011 | 46.5 |

| Jan-Mar 2010 | 86 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | 20.9 |

| Jan-Mar 2009 | 84 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | 23.8 |

| Jan-Mar 2008 | 141 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -26.2 |

| Jan-Mar 2007 | 213 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -51.1 |

| Jan-Mar 2006 | 285 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2006 | -63.5 |

| Jan-Mar 2005 | 328 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2005 | -68.3 |

| Jan-Feb 2004 | 314 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2004 | -66.9 |

| Jan-Mar 2003 | 256 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -59.4 |

| Jan-Mar 2002 | 239 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -56.5 |

| Jan-Mar 2001 | 251 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -58.6 |

| Jan-Mar 2000 | 233 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -55.4 |

| Jan-Mar 1995 | 154 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -32.5 |

| Jan-Mar 1963 | 121 |

| ∆% Jan-Mar 2013/ | -14.0 |

*Computed using unrounded data

Source: US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

Chart ESIII-1 of the US Bureau of the Census provides the entire monthly sample of new houses sold in the US between Jan 1963 and Mar 2013 without seasonal adjustment. The series is almost stationary until the 1990s. There is sharp upward trend from the early 1990s to 2005-2006 after which new single-family houses sold collapse to levels below those in the beginning of the series in the 1960s.

Chart ESIII-1, US, New Single-family Houses Sold, NSA, 1963-2013

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

ESIV Global Financial and Economic Risk. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task both for theory and measurement. The IMF (2012WEOOct) provides surveillance of the world economy with its Global Economic Outlook (WEO) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/index.htm), of the world financial system with its Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) (IMF 2012GFSROct) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2012/02/index.htm) and of fiscal affairs with the Fiscal Monitor (IMF 2012FMOct) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2012/02/fmindex.htm). There appears to be a moment of transition in global economic and financial variables that may prove of difficult analysis and measurement. It is useful to consider a summary of global economic and financial risks, which are analyzed in detail in the comments of this blog in Section VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets, Table VI-4.

Economic risks include the following:

- China’s Economic Growth. China is lowering its growth target to 7.5 percent per year. China’s GDP growth decelerated significantly from annual equivalent 9.9 percent in IIQ2011 to 7.4 percent in IVQ2011 and 6.6 percent in IQ2012, rebounding to 7.8 percent in IIQ2012, 8.7 percent in IIIQ2012 and 8.2 percent in IVQ2012. Annual equivalent growth in IQ2013 fell to 6.6 percent. (See Subsection VC and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/recovery-without-hiring-world-inflation.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/10/world-inflation-waves-stagnating-united_21.html).

- United States Economic Growth, Labor Markets and Budget/Debt Quagmire. The US is growing slowly with 29.6 million in job stress, fewer 10 million full-time jobs, high youth unemployment, historically low hiring and declining real wages.

- Economic Growth and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies. Advanced economies are growing slowly. There is still high unemployment in advanced economies.

- World Inflation Waves. Inflation continues in repetitive waves globally (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html ).

A list of financial uncertainties includes:

- Euro Area Survival Risk. The resilience of the euro to fiscal and financial doubts on larger member countries is still an unknown risk.

- Foreign Exchange Wars. Exchange rate struggles continue as zero interest rates in advanced economies induce devaluation of their currencies.

- Valuation of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with lower volumes.

- Duration Trap of the Zero Bound. The yield of the US 10-year Treasury rose from 2.031 percent on Mar 9, 2012, to 2.294 percent on Mar 16, 2012. Considering a 10-year Treasury with coupon of 2.625 percent and maturity in exactly 10 years, the price would fall from 105.3512 corresponding to yield of 2.031 percent to 102.9428 corresponding to yield of 2.294 percent, for loss in a week of 2.3 percent but far more in a position with leverage of 10:1. Min Zeng, writing on “Treasurys fall, ending brutal quarter,” published on Mar 30, 2012, in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303816504577313400029412564.html?mod=WSJ_hps_sections_markets), informs that Treasury bonds maturing in more than 20 years lost 5.52 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

- Credibility and Commitment of Central Bank Policy. There is a credibility issue of the commitment of monetary policy (Sargent and Silber 2012Mar20).

- Carry Trades. Commodity prices driven by zero interest rates have resumed their increasing path with fluctuations caused by intermittent risk aversion

A competing event is the high level of valuations of risk financial assets (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/peaking-valuation-of-risk-financial.html). Matt Jarzemsky, writing on Dow industrials set record,” on Mar 5, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324156204578275560657416332.html), analyzes that the DJIA broke the closing high of 14164.53 set on Oct 9, 2007, and subsequently also broke the intraday high of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. The DJIA closed at 14712.55

on Fri Apr 26, 2013, which is higher by 3.9 percent than the value of 14,164.53 reached on Oct 9, 2007 and higher by 3.6 percent than the value of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. Values of risk financial are approaching or exceeding historical highs.

The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets had proved strongest for commodity exposures but US equities have regained leadership. The DJIA has increased 51.9 percent since the trough of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe on Jul 2, 2010 to Apr 26, 2013, S&P 500 has gained 54.7 percent and DAX 37.8 percent. Before the current round of risk aversion, almost all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 4/26/13” in Table ESIV-1 had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010 followed by negative performance but now some valuations of equity indexes show varying behavior: China’s Shanghai Composite is 8.6 percent below the trough; Japan’s Nikkei Average is 57.3 percent above the trough; DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 25.2 percent above the trough; Dow Global is 26.4 percent above the trough; STOXX 50 of 50 blue-chip European equities (http://www.stoxx.com/indices/index_information.html?symbol=sx5E) is 18.3 percent above the trough; and NYSE Financial Index is 32.3 percent above the trough. DJ UBS Commodities is 6.4 percent above the trough. DAX index of German equities (http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/DAX:IND) is 37.8 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 57.3 percent above the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 21.9 percent above the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 13884.13

on Fri Apr 26, 2013 (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata), which is 35.4 percent higher than 10,254.43 on Mar 11, 2011, on the date of the Tōhoku or Great East Japan Earthquake/tsunami. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar depreciated by 9.3 percent relative to the euro and even higher before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 4/26/13” in Table ESIV-1 shows that there were decreases of valuations of risk financial assets in the week of Apr 26, 2013 such as 3.0 percent for China’s Shanghai Composite. DJ Asia Pacific increased 3.0 percent. NYSE Financial increased 2.8 percent in the week. DJ UBS Commodities increased 0.3 percent. Dow Global increased 2.5 percent in the week of Apr 26, 2013. The DJIA increased 1.1 percent and S&P 500 increased 1.7 percent. DAX of Germany increased 4.8 percent. STOXX 50 increased 3.5 percent. The USD appreciated 0.2 percent. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks and banking soundness, US and world growth slowdown and China’s growth tradeoffs. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table ESIV-1 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 4/26/13” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Apr 26, 2013. Most risk financial assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 4/26/13” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 4/26/13.” There are now several equity indexes above the peak in Table ESIV-1: DJIA 31.3 percent, S&P 500 30.0 percent, DAX 23.4 percent, Dow Global 3.1 percent, DJ Asia Pacific 9.6 percent, NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) 5.4 percent, Nikkei Average 21.9 percent and STOXX 50 0.2 percent. There is only one equity indexes below the peak: Shanghai Composite by 23.4 percent. DJ UBS Commodities Index is now 9.0 percent below the peak. The US dollar strengthened 13.9 percent relative to the peak. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr 2010 is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul 2010 because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. Kate Linebaugh, writing on “Falling revenue dings stocks,” on Oct 20, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444592704578066933466076070.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), identifies a key financial vulnerability: falling revenues across markets for United States reporting companies. Global economic slowdown is reducing corporate sales and squeezing corporate strategies. Linebaugh quotes data from Thomson Reuters that 100 companies of the S&P 500 index have reported declining revenue only 1 percent higher in Jun-Sep 2012 relative to Jun-Sep 2011 but about 60 percent of the companies are reporting lower sales than expected by analysts with expectation that revenue for the S&P 500 will be lower in Jun-Sep 2012 for the entities represented in the index. Results of US companies are likely repeated worldwide. It may be quite painful to exit QE→∞ or use of the balance sheet of the central together with zero interest rates forever. The basic valuation equation that is also used in capital budgeting postulates that the value of stocks or of an investment project is given by:

Where Rτ is expected revenue in the time horizon from τ =1 to T; Cτ denotes costs; and ρ is an appropriate rate of discount. In words, the value today of a stock or investment project is the net revenue, or revenue less costs, in the investment period from τ =1 to T discounted to the present by an appropriate rate of discount. In the current weak economy, revenues have been increasing more slowly than anticipated in investment plans. An increase in interest rates would affect discount rates used in calculations of present value, resulting in frustration of investment decisions. If V represents value of the stock or investment project, as ρ → ∞, meaning that interest rates increase without bound, then V → 0, or

declines. Equally, decline in expected revenue from the stock or project, Rτ, causes decline in valuation. An intriguing issue is the difference in performance of valuations of risk financial assets and economic growth and employment. Paul A. Samuelson (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1970/samuelson-bio.html).

IA Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth. The US is experiencing the first expansion from a recession after World War II without growth, jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html) and hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html), unsustainable government deficit/debt (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html), waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html) and deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates

(http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html) while valuations of risk financial assets approach historical highs. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The expansion since the third quarter of 2009 (IIIQ2009 (Jun)) to the latest available measurement for IQ(2013) has been at the average annual rate of 2.1 percent per quarter. In contrast, Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). As a result, there are 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 18.2 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html).

The economy of the US can be summarized in growth of economic activity or GDP as decelerating from mediocre growth of 2.4 percent on an annual basis in 2010 and 1.8 percent in 2011 to 2.2 percent in 2012. Calculations below show that actual growth is around 1.9 percent per year. This rate is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which has been always recovered after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May). United States real GDP grew at the rate of 3.2 percent between 1929 and 2012 and at 3.2 percent between 1947 and 2012 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html). Growth is not only mediocre but also sharply decelerating to a rhythm that is not consistent with reduction of unemployment and underemployment of 29.6 million people corresponding to 18.2 percent of the effective labor force of the United States (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). In the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013, US real GDP grew at the seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent rates of 0.1 percent in the first quarter of 2011 (IQ2011), 2.5 percent in IIQ2011, 1.3 percent in IIIQ2011, 4.1 percent in IVQ2011, 2.0 percent in IQ2012, 1.3 percent in IIQ2012, revised 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012, 0.4 percent in IVQ2012 and 2.5 percent in IQ2013. The annual equivalent rate of growth of GDP for the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 is 1.9 percent, obtained as follows. Discounting 0.1 percent to one quarter is 0.025 percent {[(1.001)1/4 -1]100 = 0.025}; discounting 2.5 percent to one quarter is 0.62 percent {[(1.025)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 4.1 percent to one quarter is 1.0 {[(1.04)1/4 -1]100; discounting 2.0 percent to one quarter is 0.50 percent {[(1.020)1/4 -1]100); discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 -1]100}; discounting 3.1 percent to one quarter is 0.77 {[(1.031)1/4 -1]100); discounting 0.4 percent to one quarter is 0.1 percent {[(1.004)1/4 – 1]100}; and discounting 2.5 percent to one quarter is 0.62 percent {[(1.025)1/4 -1}100}. Real GDP growth in the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 accumulated to 4.3 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001 x 1.0062) - 1]100 = 4.3%}. This is equivalent to growth from IQ2011 to IVQ2012 obtained by dividing the seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of IQ2013 of $13,750.1 billion by the SAAR of IVQ2010 of $13,181.2 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1 and Table I-6 below) and expressing as percentage {[($13,750.1/$13,181.2) - 1]100 = 4.3%}. The growth rate in annual equivalent for the four quarters of 2011, the four quarters of 2012 and the first quarter of 2013 is 1.9 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001 x 1.0062)4/9 -1]100 = 1.9%], or {[($13,750.1/$13,181.2)]4/9-1]100 = 1.9%} dividing the SAAR of IVQ2012 by the SAAR of IVQ2010 in Table I-6 below, obtaining the average for nine quarters and the annual average for one year of four quarters. Growth in the four quarters of 2012 accumulates to 1.7 percent {[(1.02)1/4(1.013)1/4(1.031)1/4(1.004)1/4 -1]100 = 1.7%}. This is equivalent to dividing the SAAR of $13,665.4 billion for IVQ2012 in Table I-6 by the SAAR of $13,441.0 billion in IVQ2011 except for a rounding discrepancy to obtain 1.7 percent {[($13,665.4/$13,441.0) – 1]100 = 1.7%}. The US economy is still close to a standstill especially considering the GDP report in detail.

The objective of this section is analyzing US economic growth in the current cyclical expansion. There is initial discussion of the conventional explanation of the current recovery as being weak because of the depth of the contraction and the financial crisis and also brief discussion of the concept of “slow-growth recession.” Analysis that is more complete is in IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, which is updated with release of more information on the United States economic cycle (IX Conclusion and extended analysis at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). The bulk of the section consists of comparison of the current growth experience of the US with earlier expansions after past deep contractions and consideration of recent performance.

This blog has analyzed systematically the weakness of the United States recovery in the current business cycle from IIIQ2009 to the present in comparison with the recovery from the two recessions in the 1980s from IQ1983 to IVQ1985. The United States has grown on average at 2.1 percent annual equivalent in the 15 quarters of expansion since IIIQ2009 while growth was 5.7 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1985. In contrast, Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). As a result, there are 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 18.2 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html).

The conventional explanation is that the recession from IVQ2007 (Dec) to IIQ2009 (Jun) was so profound that it caused subsequent weak recovery and that historically growth after recessions with financial crises has been weaker. Michael D. Bordo (2012Sep27) and Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR) provide evidence contradicting the conventional explanation: recovery is much stronger on average after profound contractions and also much stronger after recessions with financial crises than after recessions without financial crises. Insistence on the conventional explanation prevents finding policies that can accelerate growth, employment and prosperity.

A monumental effort of data gathering, calculation and analysis by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff is highly relevant to banking crises, financial crash, debt crises and economic growth (Reinhart 2010CB; Reinhart and Rogoff 2011AF, 2011Jul14, 2011EJ, 2011CEPR, 2010FCDC, 2010GTD, 2009TD, 2009AFC, 2008TDPV; see also Reinhart and Reinhart 2011Feb, 2010AF and Reinhart and Sbrancia 2011). See http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/debt-and-financial-risk-aversion-and.html The dataset of Reinhart and Rogoff (2010GTD, 1) is quite unique in breadth of countries and over time periods:

“Our results incorporate data on 44 countries spanning about 200 years. Taken together, the data incorporate over 3,700 annual observations covering a wide range of political systems, institutions, exchange rate and monetary arrangements and historic circumstances. We also employ more recent data on external debt, including debt owed by government and by private entities.”

Reinhart and Rogoff (2010GTD, 2011CEPR) classify the dataset of 2317 observations into 20 advanced economies and 24 emerging market economies. In each of the advanced and emerging categories, the data for countries is divided into buckets according to the ratio of gross central government debt to GDP: below 30, 30 to 60, 60 to 90 and higher than 90 (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010GTD, Table 1, 4). Median and average yearly percentage growth rates of GDP are calculated for each of the buckets for advanced economies. There does not appear to be any relation for debt/GDP ratios below 90. The highest growth rates are for debt/GDP ratios below 30: 3.7 percent for the average and 3.9 for the median. Growth is significantly lower for debt/GDP ratios above 90: 1.7 for the average and 1.9 percent for the median. GDP growth rates for the intermediate buckets are in a range around 3 percent: the highest 3.4 percent average is for the bucket 60 to 90 and 3.1 percent median for 30 to 60. There is even sharper contrast for the United States: 4.0 percent growth for debt/GDP ratio below 30; 3.4 percent growth for debt/GDP ratio of 30 to 60; 3.3 percent growth for debt/GDP ratio of 60 to 90; and minus 1.8 percent, contraction, of GDP for debt/GDP ratio above 90.

For the five countries with systemic financial crises—Iceland, Ireland, UK, Spain and the US—real average debt levels have increased by 75 percent between 2007 and 2009 (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010GTD, Figure 1). The cumulative increase in public debt in the three years after systemic banking crisis in a group of episodes after World War II is 86 percent (Reinhart and Rogoff 2011CEPR, Figure 2, 10).

An important concept is “this time is different syndrome,” which “is rooted in the firmly-held belief that financial crises are something that happens to other people in other countries at other times; crises do not happen here and now to us” (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010FCDC, 9). There is both an arrogance and ignorance in “this time is different” syndrome, as explained by Reinhart and Rogoff (2010FCDC, 34):

“The ignorance, of course, stems from the belief that financial crises happen to other people at other time in other places. Outside a small number of experts, few people fully appreciate the universality of financial crises. The arrogance is of those who believe they have figured out how to do things better and smarter so that the boom can long continue without a crisis.”

There is sober warning by Reinhart and Rogoff (2011CEPR, 42) on the basis of the momentous effort of their scholarly data gathering, calculation and analysis:

“Despite considerable deleveraging by the private financial sector, total debt remains near its historic high in 2008. Total public sector debt during the first quarter of 2010 is 117 percent of GDP. It has only been higher during a one-year sting at 119 percent in 1945. Perhaps soaring US debt levels will not prove to be a drag on growth in the decades to come. However, if history is any guide, that is a risky proposition and over-reliance on US exceptionalism may only be one more example of the “This Time is Different” syndrome.”

As both sides of the Atlantic economy maneuver around defaults the experience on debt and growth deserves significant emphasis in research and policy. The world economy is slowing with high levels of unemployment in advanced economies. Countries do not grow themselves out of unsustainable debts but rather through de facto defaults by means of financial repression and in some cases through inflation. This time is not different.

Professor Michael D. Bordo (2012Sep27), at Rutgers University, is providing clear thought on the correct comparison of the current business cycles in the United States with those in United States history. There are two issues raised by Professor Bordo: (1) incomplete conclusions by lumping together countries with different institutions, economic policies and financial systems; and (2) the erroneous contention that growth is mediocre after financial crises and deep recessions, which is repeated daily in the media, but that Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR) persuasively demonstrate to be inconsistent with United States experience.

Depriving economic history of institutions is perilous as is illustrated by the economic history of Brazil. Douglass C. North (1994) emphasized the key role of institutions in explaining economic history. Rondo E. Cameron (1961, 1967, 1972) applied institutional analysis to banking history. Friedman and Schwartz (1963) analyzed the relation of money, income and prices in the business cycle and related the monetary policy of an important institution, the Federal Reserve System, to the Great Depression. Bordo, Choudhri and Schwartz (1995) analyze the counterfactual of what would have been economic performance if the Fed had used during the Great Depression the Friedman (1960) monetary policy rule of constant growth of money(for analysis of the Great Depression see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 198-217). Alan Meltzer (2004, 2010a,b) analyzed the Federal Reserve System over its history. The reader would be intrigued by Figure 5 in Reinhart and Rogoff (2010FCDC, 15) in which Brazil is classified in external default for seven years between 1828 and 1834 but not again until 64 years later in 1989, above the 50 years of incidence for serial default. This void has been filled in scholarly research on nineteenth-century Brazil by William R. Summerhill, Jr. (2007SC, 2007IR). There are important conclusions by Summerhill on the exceptional sample of institutional change or actually lack of change, public finance and financial repression in Brazil between 1822 an 1899, combining tools of economics, political science and history. During seven continuous decades, Brazil did not miss a single interest payment with government borrowing without repudiation of debt or default. What is really surprising is that Brazil borrowed by means of long-term bonds and even more surprising interest rates fell over time. The external debt of Brazil in 1870 was ₤41,275,961 and the domestic debt in the internal market was ₤25,708,711, or 62.3 percent of the total (Summerhill 2007IR, 73).

The experience of Brazil differed from that of Latin America (Summerhill 2007IR). During the six decades when Brazil borrowed without difficulty, Latin American countries becoming independent after 1820 engaged in total defaults, suffering hardship in borrowing abroad. The countries that borrowed again fell again in default during the nineteenth century. Venezuela defaulted in four occasions. Mexico defaulted in 1827, rescheduling its debt eight different times and servicing the debt sporadically. About 44 percent of Latin America’s sovereign debt was in default in 1855 and approximately 86 percent of total government loans defaulted in London originated in Spanish American borrowing countries.

External economies of commitment to secure private rights in sovereign credit would encourage development of private financial institutions, as postulated in classic work by North and Weingast (1989), Summerhill 2007IR, 22). This is how banking institutions critical to the Industrial Revolution were developed in England (Cameron 1967). The obstacle in Brazil found by Summerhill (2007IR) is that sovereign debt credibility was combined with financial repression. There was a break in Brazil of the chain of effects from protecting public borrowing, as in North and Weingast (1989), to development of private financial institutions. According to Pelaez 1976, 283) following Cameron (1971, 1967):

“The banking law of 1860 placed severe restrictions on two basic modern economic institutions—the corporation and the commercial bank. The growth of the volume of bank credit was one of the most significant factors of financial intermediation and economic growth in the major trading countries of the gold standard group. But Brazil placed strong restrictions on the development of banking and intermediation functions, preventing the channeling of coffee savings into domestic industry at an earlier date.”

Brazil actually abandoned the gold standard during multiple financial crises in the nineteenth century, as it should have to protect domestic economic activity. Pelaez (1975, 447) finds similar experience in the first half of nineteenth-century Brazil:

“Brazil’s experience is particularly interesting in that in the period 1808-1851 there were three types of monetary systems. Between 1808 and 1829, there was only one government-related Bank of Brazil, enjoying a perfect monopoly of banking services. No new banks were established in the 1830s after the liquidation of the Bank of Brazil in 1829. During the coffee boom in the late 1830s and 1840s, a system of banks of issue, patterned after similar institutions in the industrial countries, supplied the financial services required in the first stage of modernization of the export economy.”

Financial crises in the advanced economies were transmitted to nineteenth-century Brazil by the arrival of a ship (Pelaez and Suzigan 1981). The explanation of those crises and the economy of Brazil requires knowledge and roles of institutions, economic policies and the financial system chosen by Brazil, in agreement with Bordo (2012Sep27).

The departing theoretical framework of Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR) is the plucking model of Friedman (1964, 1988). Friedman (1988, 1) recalls “I was led to the model in the course of investigating the direction of influence between money and income. Did the common cyclical fluctuation in money and income reflect primarily the influence of money on income or of income on money?” Friedman (1964, 1988) finds useful for this purpose to analyze the relation between expansions and contractions. Analyzing the business cycle in the United States between 1870 and 1961, Friedman (1964, 15) found that “a large contraction in output tends to be followed on the average by a large business expansion; a mild contraction, by a mild expansion.” The depth of the contraction opens up more room in the movement toward full employment (Friedman 1964, 17):

“Output is viewed as bumping along the ceiling of maximum feasible output except that every now and then it is plucked down by a cyclical contraction. Given institutional rigidities and prices, the contraction takes in considerable measure the form of a decline in output. Since there is no physical limit to the decline short of zero output, the size of the decline in output can vary widely. When subsequent recovery sets in, it tends to return output to the ceiling; it cannot go beyond, so there is an upper limit to output and the amplitude of the expansion tends to be correlated with the amplitude of the contraction.”

Kim and Nelson (1999) test the asymmetric plucking model of Friedman (1964, 1988) relative to a symmetric model using reference cycles of the NBER, finding evidence supporting the Friedman model. Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR) analyze 27 cycles beginning in 1872, using various measures of financial crises while considering different regulatory and monetary regimes. The revealing conclusion of Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR, 2) is that:

“Our analysis of the data shows that steep expansions tend to follow deep contractions, though this depends heavily on when the recovery is measured. In contrast to much conventional wisdom, the stylized fact that deep contractions breed strong recoveries is particularly true when there is a financial crisis. In fact, on average, it is cycles without a financial crisis that show the weakest relation between contraction depth and recovery strength. For many configurations, the evidence for a robust bounce-back is stronger for cycles with financial crises than those without.”

The average rate of growth of real GDP in expansions after recessions with financial crises was 8 percent but only 6.9 percent on average for recessions without financial crises (Bordo 2012Sep27). Real GDP declined 12 percent in the Panic of 1907 and increased 13 percent in the recovery, consistent with the plucking model of Friedman (Bordo 2012Sep27). The comparison of recovery from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 is appropriate even when considering financial crises. There was significant financial turmoil during the 1980s. Bordo and Haubrich (2012DR, 11) identify a financial crisis in the United States starting in 1981. Benston and Kaufman (1997, 139) find that there was failure of 1150 US commercial and savings banks between 1983 and 1990, or about 8 percent of the industry in 1980, which is nearly twice more than between the establishment of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 1934 through 1983. More than 900 savings and loans associations, representing 25 percent of the industry, were closed, merged or placed in conservatorships (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2008b), 74-7). The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) and the Savings Association Insurance Fund (SAIF) that received $150 billion of taxpayer funds to resolve insolvent savings and loans. The GDP of the US in 1989 was $5482.1 billion (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm), such that the partial cost to taxpayers of that bailout was around 2.74 percent of GDP in a year. US GDP in 2011 is estimated at $15,075.7 billion, such that the bailout would be equivalent to cost to taxpayers of about $412.5 billion in current GDP terms. A major difference with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) for private-sector banks is that most of the costs were recovered with interest gains whereas in the case of savings and loans there was no recovery. Money center banks were under extraordinary pressure from the default of sovereign debt by various emerging nations that represented a large share of their net worth (see Pelaez 1986).

Bordo (2012Sep27) finds two probable explanations for the weak recovery during the current economic cycle: (1) collapse of United States housing; and (2) uncertainty originating in fiscal policy, regulation and structural changes. There are serious doubts if monetary policy is adequate to recover the economy under these conditions.

The concept of growth recession was popular during the stagflation from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. The economy of the US underperformed with several recession episodes in “stop and go” fashion of policy and economic activity while the rate of inflation rose to the highest in a peacetime period (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/risk-aversion-and-stagflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/global-inflation-seigniorage-monetary.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html Appendix I; see Taylor 1993, 1997, 1999, 1998LB, 2012Mar27, 2012Mar28, 2012FP, 2012JMCB). A growth recession could be defined as a period in which economic growth is insufficient to move the economy toward full employment of humans, equipment and other productive resources. The US is experiencing a dramatic slow growth recession with 29.550 million people in job stress, consisting of an effective number of unemployed of 19.490 million, 7.734 million employed part-time because they cannot find full employment and 2.326 million marginally attached to the labor force (see Table I-4 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). The discussion of the growth recession issue in the 1970s by two recognized economists of the twentieth century, James Tobin and Paul A. Samuelson, is worth recalling.

In analysis of the design of monetary policy in 1974, Tobin (1974, 219) finds that the forecast of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) was also the target such that monetary policy would have to be designed and implemented to attain that target. The concern was with maintaining full employment as provided in the Employment Law of 1946 (http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/15/1021.html http://uscode.house.gov/download/pls/15C21.txt http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED164974.pdf) see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html), which also created the CEA. Tobin (1974, 219) describes the forecast/target of the CEA for 1974:

“The expected and approved path appears to be quarter-to-quarter rates of growth of real gross national product in 1974 of roughly -0.5, 0.1, and 1 percent, with unemployment rising to about 5.6 percent in the second quarter and remaining there the rest of the year. The rate of price inflation would fall shortly in the second quarter, but rise slightly toward the end of the year.”

Referring to monetary policy design, Tobin (1974, 221) states: “if interest rates remain stable or rise during the current (growth) recession and recovery, this will be a unique episode in business cycle annals.” Subpar economic growth is often called a “growth recession.” The critically important concept is that economic growth is not sufficient to move the economy toward full employment, creating the social and economic adverse outcome of idle capacity and unemployed and underemployed workers, much the same as currently.

The unexpected incidence of inflation surprises during growth recessions is considered by Samuelson (1974, 76):

“Indeed, if there were in Las Vegas or New York a continuous casino on the money GNP of 1974’s fourth quarter, it would be absurd to think that the best economic forecasters could improve upon the guess posted there. Whatever knowledge and analytical skill they possess would already have been fed into the bidding. It is a manifest contradiction to think that most economists can be expected to do better than their own best performance. I am saying that the best forecasters have been poor in predicting the general price level’s movements and level even a year ahead. By Valentine’s Day 1973 the best forecasters were beginning to talk of the growth recession that we now know did set in at the end of the first quarter. Aside from their end-of-1972 forecasts, the fashionable crowd has little to blame itself for when it comes to their 1973 real GNP projections. But, of course, they did not foresee the upward surge of food and decontrolled industrial prices. This has been a recurring pattern: surprise during the event at the virulence of inflation, wisdom after the event in demonstrating that it did, after all, fit with past patterns of experience.”

Economists are known for their forecasts being second only to those of astrologers. Accurate forecasts are typically realized for the wrong reasons. In contrast with meteorologists, economists do not even agree on what happened. There is not even agreement on what caused the global recession and why the economy has reached a perilous standstill.

Historical parallels are instructive but have all the limitations of empirical research in economics. The more instructive comparisons are not with the Great Depression of the 1930s but rather with the recessions in the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s. The growth rates and job creation in the expansion of the economy away from recession are subpar in the current expansion compared to others in the past. Four recessions are initially considered, following the reference dates of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html ): IIQ1953-IIQ1954, IIIQ1957-IIQ1958, IIIQ1973-IQ1975 and IQ1980-IIIQ1980. The data for the earlier contractions illustrate that the growth rate and job creation in the current expansion are inferior. The sharp contractions of the 1950s and 1970s are considered in Table I-1, showing the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) quarter-to-quarter, seasonally adjusted (SA), yearly-equivalent growth rates of GDP. The recovery from the recession of 1953 consisted of four consecutive quarters of high percentage growth rates from IIIQ1954 to IIIQ1955: 4.6, 8.3, 12.0, 6.8 and 5.4. The recession of 1957 was followed by four consecutive high percentage growth rates from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959: 9.7, 9.7, 8.3 and 10.5. The recession of 1973-1975 was followed by high percentage growth rates from IIQ1975 to IIQ1976: 6.9, 5.3, 9.4 and 3.0. The disaster of the Great Inflation and Unemployment of the 1970, which made stagflation notorious, is even better in growth rates during the expansion phase in comparison with the current slow-growth recession.

Table I-1, US, Quarterly Growth Rates of GDP, % Annual Equivalent SA

| IQ | IIQ | IIIQ | IVQ | |

| 1953 | 7.7 | 3.1 | -2.4 | -6.2 |

| 1954 | -1.9 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

| 1955 | 12.0 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 2.2 |

| 1957 | 2.5 | -1.0 | 3.9 | -4.1 |

| 1958 | -10.4 | 2.5 | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| 1959 | 8.3 | 10.5 | -0.5 | 1.4 |

| 1973 | 10.6 | 4.7 | -2.1 | 3.9 |

| 1974 | 3.5 | 1.0 | -3.9 | 6.9 |

| 1975 | -4.8 | 3.1 | 6.9 | 5.3 |

| 1976 | 9.4 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

| 1979 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| 1980 | 1.3 | -7.9 | -0.7 | 7.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The NBER dates another recession in 1980 that lasted about half a year. If the two recessions from IQ1980s to IIIQ1980 and IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 are combined, the impact of lost GDP of 4.8 percent is more comparable to the latest revised 4.7 percent drop of the recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. The recession in 1981-1982 is quite similar on its own to the 2007-2009 recession. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.5 percent cumulatively and fell 45.6 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7). Table I-2 provides the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) quarterly growth rates of GDP in SA yearly equivalents for the recessions of 1981 to 1982 and 2007 to 2009, using the latest major revision published on Jul 29, 2011 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2011/pdf/gdp2q11_adv.pdf) and the revision back to 2009 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2012/pdf/gdp2q12_adv.pdf) and the first estimate for IQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp1q13_adv.pdf), which are available in the dataset of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). There were four quarters of contraction in 1981-1982 ranging in rate from -1.5 percent to -6.4 percent and five quarters of contraction in 2007-2009 ranging in rate from -0.3 percent to -8.9 percent. The striking difference is that in the first fifteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, shown in Table I-2 in relief, GDP grew at the high quarterly percentage growth rates of 5.1, 9.3, 8.1, 8.5, 8.0, 7.1, 3.9, 3.3, 3.8, 3.4, 6.4, 3.1, 3.9, 1.6 and 3.9 while the percentage growth rates in the first fourteen quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2012, shown in relief in Table I-2, were mediocre: 1.4, 4.0, 2.3, 2.2, 2.6, 2.4, 0.1, 2.5, 1.3, 4.1, 2.0, 1.3, 3.1, 0.4 and 2.5. Asterisks denote the estimates that have been revised by the BEA in the first round of Jul 29, 2011 and double asterisks the revisions released on Jul 27, 2012. During the four quarters of 2011 GDP grew at annual equivalent rates of 0.1 percent in IQ2011, 2.5 percent in IIQ2011, 1.3 percent in IIIQ2011 and 4.1 percent in IVQ2011. The rate of growth of the US economy decelerated from seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent of 4.1 percent in IVQ2011 to 2.0 percent in IQ2012, 1.3 percent in IIQ2012, 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012, which is more like 1.73 percent without contributions of 0.73 percentage points by inventory change and 0.64 percentage points by one-time expenditures in national defense and 0.4 percent in IVQ2012, which is more like 3.2 percent without deductions of 1.52 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.28 percent of reductions of one-time national defense expenditures. Inventory change contributed to initial growth but was rapidly replaced by growth in investment and demand in 1983. Inventory accumulation contributed 2.53 percentage points to the rate of growth of 4.1 percent in IVQ2011, which is the only relatively high rate from IQ2011 to IIIQ2012, and 0.73 percentage points to the rate of 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012. Economic growth and employment creation decelerated rapidly during 2012 and in 2013 as would be required from movement to full employment.

Table I-2, US, Quarterly Growth Rates of GDP, % Annual Equivalent SA

| Q | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| I | 8.6 | -6.4 | 5.1 | 8.0 | -1.8* | -5.3** | 2.3** |

| II | -3.2 | 2.2 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 1.3* | -0.3** | 2.2** |

| III | 4.9 | -1.5 | 8.1 | 3.9 | -3.7* | 1.4** | 2.6** |

| IV | -4.9 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 3.3 | -8.9* | 4.0** | 2.4** |

| 1985 | 2011 | ||||||

| I | 3.8 | 0.1** | |||||

| II | 3.4 | 2.5** | |||||

| III | 6.4 | 1.3** | |||||

| IV | 3.1 | 4.1** | |||||

| 1986 | 2012 | ||||||

| I | 3.9 | 2.0** | |||||

| II | 1.6 | 1.3 | |||||

| III | 3.9 | 3.1 | |||||

| IV | 1.9 | 0.4 | |||||

| 1987 | 2013 | ||||||

| I | 2.2 | 2.5 | |||||

| II | 4.3 | ||||||

| III | 3.5 | ||||||

| IV | 7.0 |

*Revision of Jul 29, 2011 **Revision of Jul 27, 2012

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

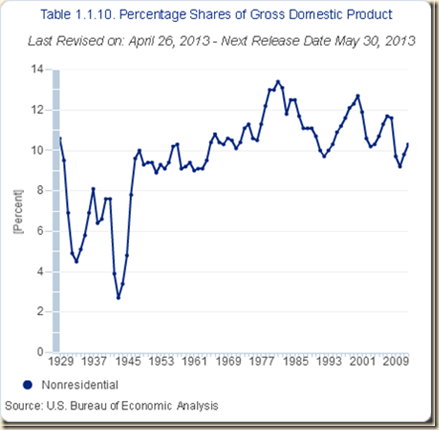

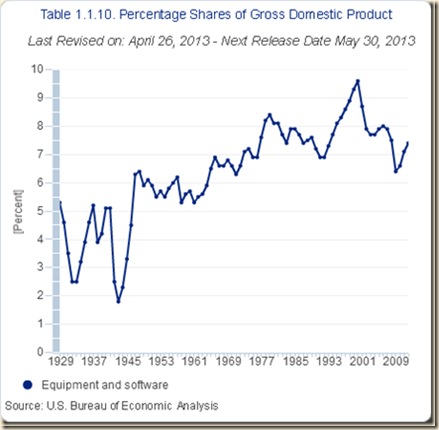

Chart I-1 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides strong growth of real GDP in the US between 1947 and 1999 at the yearly average rate of 3.5 percent. There is an evident acceleration of the rate of GDP growth in the 1990s as shown by a much sharper slope of the growth curve. Cobet and Wilson (2002) define labor productivity as the value of manufacturing output produced per unit of labor input used (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 137-44). Between 1950 and 2000, labor productivity in the US grew less rapidly than in Germany and Japan. The major part of the increase in productivity in Germany and Japan occurred between 1950 and 1973 while the rate of productivity growth in the US was relatively subdued in several periods. While Germany and Japan reached their highest growth rates of productivity before 1973, the US accelerated its rate of productivity growth in the second half of the 1990s. Between 1950 and 2000, the rate of productivity growth in the US of 2.9 percent per year was much lower than 6.3 percent in Japan and 4.7 percent in Germany. Between 1995 and 2000, the rate of productivity growth of the US of 4.6 percent exceeded that of Japan of 3.9 percent and the rate of Germany of 2.6 percent.

Chart I-1, US, Real GDP 1947-1999

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

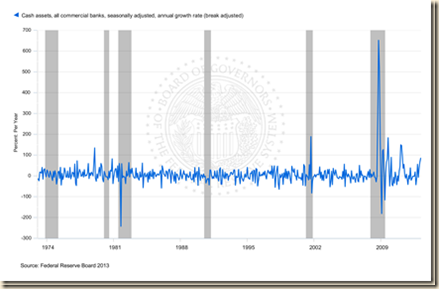

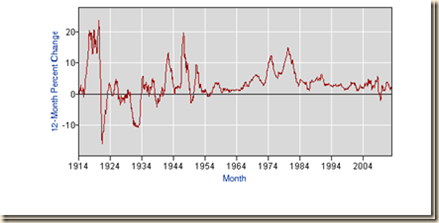

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm