Rules, Discretionary Authorities and Slow Productivity Growth, Twenty Nine Million Unemployed or Underemployed, Stagnating Wages and Real Disposable Income per Capita, United States International Trade, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Executive Summary

I Twenty Nine Million Unemployed or Underemployed

IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation

IA2 Number of People in Job Stress

IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment

IA4 Job Creation

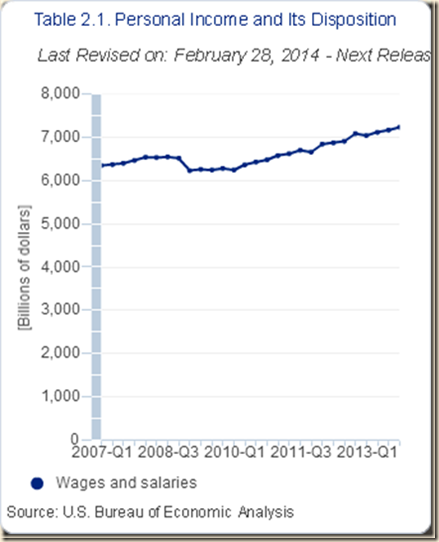

IB Stagnating Real Wages

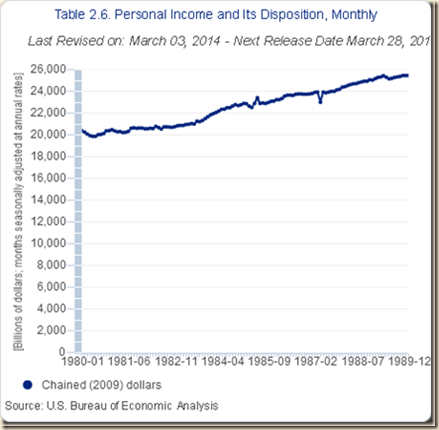

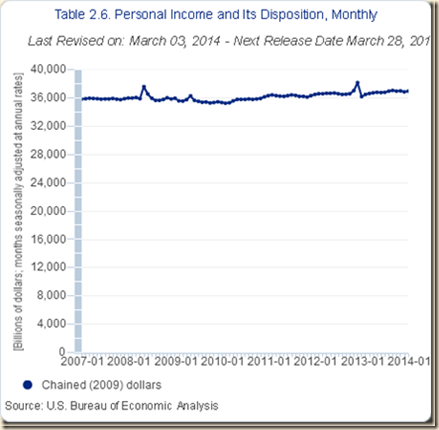

IC Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

II Rules, Discretionary Authorities and Slow Productivity Growth

IIA United States International Trade

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

I Twenty Nine Million Unemployed or Underemployed. This section analyzes the employment situation report of the United States of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). There are four subsections: IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation; IA2 Number of People in Job Stress; IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment; and IA4 Job Creation.

IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation. Table I-1 provides summary statistics of the employment situation report of the BLS. The first four rows provide the data from the establishment report of creation of nonfarm payroll jobs and remuneration of workers (for analysis of the differences in employment between the establishment report and the household survey see Abraham, Haltiwanger, Sandusky and Spletzer 2009). Total nonfarm payroll employment seasonally adjusted (SA) increased 175,000 in Feb 2014 and private payroll employment rose 162,000. The average number of nonfarm jobs created from Feb 2012 to Feb 2013 was 177,250, using seasonally adjusted data, while the average number of nonfarm jobs created from Feb 2013 to Feb 2014 was 179,833, or increase by 1.5 percent. The average number of private jobs created in the US from Feb 2012 to Feb 2013 was 182,000, using seasonally adjusted data, while the average from Feb 2013 to Feb 2014 was 182,500, or increase by 0.3 percent. This blog calculates the effective labor force of the US at 162.076 million in Feb 2013 and 163.570 million in Feb 2014 (Table I-4), for growth of 1.494 million at average 124,500 per month. The difference between the average increase of 182,500 new private nonfarm jobs per month in the US from Feb 2013 to Feb 2014 and the 124,500 average monthly increase in the labor force from Feb 2013 to Feb 2014 is 58,000 monthly new jobs net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force. There are 29.136 million in job stress in the US currently. Creation of 58,000 new jobs per month net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force would require 502 months to provide jobs for the unemployed and underemployed (29.136 million divided by 58,000) or 42 years (502 divided by 12). The civilian labor force of the US in Feb 2014 not seasonally adjusted stood at 155.027 million with 10.893 million unemployed or effectively 19.436 million unemployed in this blog’s calculation by inferring those who are not searching because they believe there is no job for them for effective labor force of 163.570 million. Reduction of one million unemployed at the current rate of job creation without adding more unemployment requires 1.4 years (1 million divided by product of 58,000 by 12, which is 696,000). Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would be equivalent to unemployment of only 7.751 million (0.05 times labor force of 155.027 million) for new net job creation of 3.142 million (10.893 million unemployed minus 7.751 million unemployed at rate of 5 percent) that at the current rate would take 4.5 years (3.142 million divided by 0.696000). Under the calculation in this blog, there are 19.436 million unemployed by including those who ceased searching because they believe there is no job for them and effective labor force of 163.570 million. Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would require creating 11.257 million jobs net of labor force growth that at the current rate would take 16.2 years (19.436 million minus 0.05(163.570 million) = 11.257 million divided by 0.696000, using LF PART 66.2% and Total UEM in Table I-4). These calculations assume that there are no more recessions, defying United States economic history with periodic contractions of economic activity when unemployment increases sharply. The number employed in Feb 2014 was 144.134 million (NSA) or 3.181 million fewer people with jobs relative to the peak of 147.315 million in Jul 2007 while the civilian noninstitutional population increased from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 247.085 million in Feb 2014 or by 15.127 million. The number employed fell 2.2 percent from Jul 2007 to Feb 2014 while population increased 6.5 percent. There is actually not sufficient job creation in merely absorbing new entrants in the labor force because of those dropping from job searches, worsening the stock of unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs.

There is current interest in past theories of “secular stagnation.” Alvin H. Hansen (1939, 4, 7; see Hansen 1938, 1941; for an early critique see Simons 1942) argues:

“Not until the problem of full employment of our productive resources from the long-run, secular standpoint was upon us, were we compelled to give serious consideration to those factors and forces in our economy which tend to make business recoveries weak and anaemic (sic) and which tend to prolong and deepen the course of depressions. This is the essence of secular stagnation-sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions which feed on them-selves and leave a hard and seemingly immovable core of unemployment. Now the rate of population growth must necessarily play an important role in determining the character of the output; in other words, the com-position of the flow of final goods. Thus a rapidly growing population will demand a much larger per capita volume of new residential building construction than will a stationary population. A stationary population with its larger proportion of old people may perhaps demand more personal services; and the composition of consumer demand will have an important influence on the quantity of capital required. The demand for housing calls for large capital outlays, while the demand for personal services can be met without making large investment expenditures. It is therefore not unlikely that a shift from a rapidly growing population to a stationary or declining one may so alter the composition of the final flow of consumption goods that the ratio of capital to output as a whole will tend to decline.”

The argument that anemic population growth causes “secular stagnation” in the US (Hansen 1938, 1939, 1941) is as misplaced currently as in the late 1930s (for early dissent see Simons 1942). There is currently population growth in the ages of 16 to 24 years but not enough job creation and discouragement of job searches for all ages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html). The proper explanation is not in secular stagnation but in cyclically slow growth. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,107.4 billion than actual $15,932.9 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html). US GDP grew from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,932.9 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.2 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. This is merely another case of theory without reality with dubious policy proposals. Subsection IA4 Job Creation analyzes the types of jobs created, which are lower paying than earlier. Average hourly earnings in Feb 2014 were $24.31 seasonally adjusted (SA), increasing 2.8 percent not seasonally adjusted (NSA) relative to Feb 2013 and increasing 0.4 percent relative to Jan 2014 seasonally adjusted. In Jan 2014, average hourly earnings seasonally adjusted were $24.22, increasing 1.9 percent relative to Jan 2013 not seasonally adjusted and increasing 0.2 percent seasonally adjusted relative to Dec 2013. These are nominal changes in workers’ wages. The following row “average hourly earnings in constant dollars” provides hourly wages in constant dollars calculated by the BLS or what is called “real wages” adjusted for inflation. Data are not available for Feb 2013 because the prices indexes of the BLS for Feb 2014 will only be released on Mar 18, 2014 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/), which will be covered in this blog’s comment on Mar 23, 2014, together with world inflation. The second column provides changes in real wages for Jan 2014. Average hourly earnings adjusted for inflation or in constant dollars increased 0.4 percent in Jan 2014 relative to Jan 2013 but have been decreasing during multiple months. World inflation waves in bouts of risk aversion (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html) mask declining trend of real wages. The fractured labor market of the US is characterized by high levels of unemployment and underemployment together with falling real wages or wages adjusted for inflation (Section IB and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html) in a recovery without hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html). The following section IB Stagnating Real Wages provides more detailed analysis. Average weekly hours of US workers seasonally adjusted remained virtually unchanged at 34.2. Another headline number widely followed is the unemployment rate or number of people unemployed as percent of the labor force. The unemployment rate calculated in the household survey increased from 6.6 percent in Jan 2014 to 6.7 percent in Feb 2014, seasonally adjusted. This blog provides with every employment situation report the number of people in the US in job stress or unemployed plus underemployed calculated without seasonal adjustment (NSA) at 29.1 million in Feb 2014 and 30.3 million in Jan 2014. The final row in Table I-1 provides the number in job stress as percent of the actual labor force calculated at 17.8 percent in Feb 2014 and 18.5 percent in Jan 2014. Almost one in every five workers in the US is unemployed or underemployed. There is socio-economic stress in the combination of adverse events and cyclical performance:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and about two trillion dollar below long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/financial-risks-slow-cyclical-united.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html)

- Private fixed investment declining 2.7 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IVQ2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/financial-risks-slow-cyclical-united.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html)

- Twenty nine million or 17.8 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (Section IC and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html)

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity Section IC and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html)

- 47 million in poverty and 48 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1995 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by total 1.9 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2013 in contrast with growth at 3.0 percent per year in real terms from 1945 to 2012 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html)

Table I-1, US, Summary of the Employment Situation Report SA

| Feb 2014 | Jan 2014 | |

| New Nonfarm Payroll Jobs | 175,000 | 129,000 |

| New Private Payroll Jobs | 162,000 | 145,000 |

| Average Hourly Earnings | Feb 14 $24.31 SA ∆% Feb 14/ Feb 13 NSA: 2.8 ∆% Feb 14/Jan 14 SA: 0.4 | Jan 14 $24.22 SA ∆% Jan 14/Jan 13 NSA: 1.9 ∆% Jan 14/Dec 13 SA: 0.2 |

| Average Hourly Earnings in Constant Dollars | ∆% Jan 2014/Jan 2013: 0.4 | |

| Average Weekly Hours | 34.2 SA 34.3 NSA | 34.3 SA 34.0 NSA |

| Unemployment Rate Household Survey % of Labor Force SA | 6.7 | 6.6 |

| Number in Job Stress Unemployed and Underemployed Blog Calculation | 29.1 million NSA | 30.3 million NSA |

| In Job Stress as % Labor Force | 17.8 NSA | 18.5 NSA |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the US Department of Labor provides both seasonally adjusted (SA) and not-seasonally adjusted (NSA) or unadjusted data with important uses (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2012Feb3; 2011Feb11):

“Most series published by the Current Employment Statistics program reflect a regularly recurring seasonal movement that can be measured from past experience. By eliminating that part of the change attributable to the normal seasonal variation, it is possible to observe the cyclical and other nonseasonal movements in these series. Seasonally adjusted series are published monthly for selected employment, hours, and earnings estimates.”

Requirements of using best available information and updating seasonality factors affect the comparability over time of United States employment data. In the first month of the year, the BLS revises data for several years by adjusting benchmarks and seasonal factors (page 4 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf ), which is the case of the data for Jan 2014 released on Feb 7, 2014:

“In accordance with annual practice, the establishment survey data released today [Feb 7, 2014] have been benchmarked to reflect comprehensive counts of payroll jobs for March 2013. These counts are derived principally from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), which enumerates jobs covered by the UI tax system. The benchmark process results in revisions to not seasonally adjusted data from April 2012 forward. Seasonally adjusted data from January 2009 forward are subject to revision. In addition, data for some series prior to 2009, both seasonally adjusted and unadjusted, incorporate revisions.”

The range of differences in total nonfarm employment in revisions in Table A of the employment situation report for Jan 2014 (page 5 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf) is from minus 1,000 for Mar 2013 to 274,000 for Nov 2013. There are also adjustments of population that affect comparability of labor statistics over time (page 6 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf):

“Effective with data for January 2014, updated population estimates have been used in the household survey. Population estimates for the household survey are developed by the U.S. Census Bureau. Each year, the Census Bureau updates the estimates to reflect new information and assumptions about the growth of the population since the previous decennial census. The change in population reflected in the new estimates results from adjustments for net international migration, updated vital statistics and other information, and some methodological changes in the estimation process.

In accordance with usual practice, BLS will not revise the official household survey estimates for

December 2013 and earlier months. To show the impact of the population adjustments, however, differences in selected December 2013 labor force series based on the old and new population estimates are shown in table B.

The adjustments increased the estimated size of the civilian noninstitutional population in December by 2,000, the civilian labor force by 24,000, employment by 22,000, and unemployment by 2,000. The number of persons not in the labor force was reduced by 22,000. The total unemployment rate, employment-population ratio, and labor force participation rate were unaffected.

Data users are cautioned that these annual population adjustments can affect the comparability of household data series over time. Table C shows the effect of the introduction of new population estimates on the comparison of selected labor force measures between December 2013 and January 2014. Additional information on the population adjustments and their effect on national labor force estimates is available at www.bls.gov/cps/cps14adj.pdf (emphasis added).”

There are also adjustments of benchmarks and seasonality factors for establishment data that affect comparability over time (page 1 at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf):

“Establishment survey data have been revised as a result of the annual benchmarking process and the updating of seasonal adjustment factors. Also, household survey data for January 2014 reflect updated population estimates. See the notes beginning on page 4 for more information about these changes.”

All comparisons over time are affected by yearly adjustments of benchmarks and seasonality factors. All data in this blog comment use revised data released by the BLS on Feb 7, 2014 (http://www.bls.gov/).

IA2 Number of People in Job Stress. There are two approaches to calculating the number of people in job stress. The first approach consists of calculating the number of people in job stress unemployed or underemployed with the raw data of the employment situation report as in Table I-2. The data are seasonally adjusted (SA). The first three rows provide the labor force and unemployed in millions and the unemployment rate of unemployed as percent of the labor force. There is decrease in the number unemployed from 10.351 million in Dec 2013 to 10.236 million in Jan 2014 and increase to 10.459 million in Feb 2014. The rate of unemployment decreased from 6.7 percent in Dec 2013 to 6.6 percent in Jan 2014 and increased to 6.7 percent in Feb 2014. An important aspect of unemployment is its persistence for more than 27 weeks with 3.646 million in Jan 2014, corresponding to 35.6 percent of the unemployed. The longer the period of unemployment the lower are the chances of finding another job with many long-term unemployed ceasing to search for a job. Another key characteristic of the current labor market is the high number of people trying to subsist with part-time jobs because they cannot find full-time employment or part-time for economic reasons. The BLS explains as follows: “these individuals were working part time because their hours had been cut back or because they were unable to find full-time work” (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf 2). The number of part-time for economic reasons decreased from 7.771 million in Dec 2013 to 7.257 million in Jan 2014 and decreased to 7.186 million in Feb 2014. Another important fact is the marginally attached to the labor force. The BLS explains as follows: “these individuals were not in the labor force, wanted and were available for work, and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months. They were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey” (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf 2). The number in job stress unemployed or underemployed of 19.948 million in Feb 2014 is composed of 10.459 million unemployed (of whom 3.849 million, or 36.8 percent, unemployed for 27 weeks or more) compared with 10.236 million unemployed in Jan 2014 (of whom 3.646 million, or 35.6 percent, unemployed for 27 weeks or more), 7.186 million employed part-time for economic reasons in Feb 2014 (who suffered reductions in their work hours or could not find full-time employment) compared with 7.257 million in Jan 2014 and 2.303 million who were marginally attached to the labor force in Feb 2014 (who were not in the labor force but wanted and were available for work) compared with 2.303 million in Jan 2014. The final row in Table I-2 provides the number in job stress as percent of the labor force: 12.8 percent in Feb 2014, which is close to 12.9 percent in Jan 2014 and 13.3 percent in Dec 2013.

Table I-2, US, People in Job Stress, Millions and % SA

| 2013-2014 | Feb 2014 | Jan 2014 | Dec 2013 |

| Labor Force Millions | 155.724 | 155.460 | 154.937 |

| Unemployed | 10.459 | 10.236 | 10.351 |

| Unemployment Rate (unemployed as % labor force) | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 |

| Unemployed ≥27 weeks | 3.849 | 3.646 | 3.878 |

| Unemployed ≥27 weeks % | 36.8 | 35.6 | 37.5 |

| Part Time for Economic Reasons | 7.186 | 7.257 | 7.771 |

| Marginally | 2.303 | 2.592 | 2.427 |

| Job Stress | 19.948 | 20.085 | 20.549 |

| In Job Stress as % Labor Force | 12.8 | 12.9 | 13.3 |

Job Stress = Unemployed + Part Time Economic Reasons + Marginally Attached Labor Force

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-3 repeats the data in Table I-2 but including Nov and additional data. What really matters is the number of people with jobs or the total employed, representing the opportunity for exit from unemployment. The final row of Table I-3 provides people employed as percent of the population or employment to population ratio. The number has remained relatively constant around 58.7 percent, declining to 58.6 percent in Dec 2013 and increasing to 58.8 in Jan 2014 and 58.8 in Feb 2014. The employment to population ratio fell from an annual level of 63.1 percent in 2006 to 58.6 percent in 2012 and 58.6 percent in 2013 with the lowest level at 58.4 percent in 2011.

Table I-3, US, Unemployment and Underemployment, SA, Millions and Percent

| Feb 2014 | Jan 2014 | Dec 2013 | Nov 2013 | |

| Labor Force | 155.724 | 155.460 | 154.937 | 155.284 |

| Unemployed | 10.459 | 10.236 | 10.351 | 10.841 |

| UNE Rate % | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.0 |

| Part Time Economic Reasons | 7.186 | 7.257 | 7.771 | 7.723 |

| Marginally Attached to Labor Force | 2.303 | 2.592 | 2.427 | 2.096 |

| In Job Stress | 19,948 | 20.085 | 20.549 | 20.660 |

| In Job Stress % Labor Force | 12.8 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 13.3 |

| Employed | 145.266 | 145.224 | 144.586 | 144.443 |

| Employment % Population | 58.8 | 58.8 | 58.6 | 58.6 |

Job Stress = Unemployed + Part Time Economic Reasons + Marginally Attached Labor Force

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

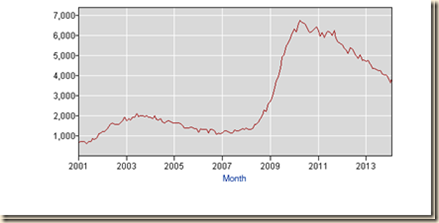

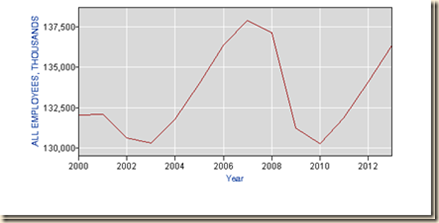

The balance of this section considers the second approach. Charts I-1 to I-12 explain the reasons for considering another approach to calculating job stress in the US. Chart I-1 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the level of employment in the US from 2001 to 2014. There was a big drop of the number of people employed from 147.315 million at the peak in Jul 2007 (NSA) to 136.809 million at the trough in Jan 2010 (NSA) with 10.506 million fewer people employed. Recovery has been anemic compared with the shallow recession of 2001 that was followed by nearly vertical growth in jobs. The number employed in Feb 2014 was 144.134 million (NSA) or 3.181 million fewer people with jobs relative to the peak of 147.315 million in Jul 2007 while the civilian noninstitutional population increased from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 247.085 million in Feb 2014 or by 15.127 million. The number employed fell 2.2 percent from Jul 2007 to Feb 2014 while population increased 6.5 percent. There is actually not sufficient job creation in merely absorbing new entrants in the labor force because of those dropping from job searches, worsening the stock of unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs.

Chart I-1, US, Employed, Thousands, SA, 2001-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

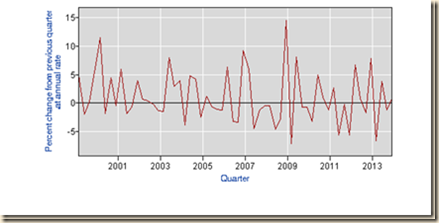

Chart I-2 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides 12-month percentage changes of the number of people employed in the US from 2001 to 2014. There was recovery since 2010 but not sufficient to recover lost jobs. Many people in the US who had jobs before the global recession are not working now.

Chart I-2, US, Employed, 12-Month Percentage Change NSA, 2001-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The foundation of the second approach derives from Chart II-3 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics providing the level of the civilian labor force in the US. The civilian labor force consists of people who are available and willing to work and who have searched for employment recently. The labor force of the US grew 9.4 percent from 142.828 million in Jan 2001 to 156.255 million in Jul 2009 but is lower at 155.027 million in Feb 2014, all numbers not seasonally adjusted. Chart I-3 shows the flattening of the curve of expansion of the labor force and its decline in 2010 and 2011. The ratio of the labor force of 154.871 million in Jul 2007 to the noninstitutional population of 231.958 million in Jul 2007 was 66.8 percent while the ratio of the labor force of 155.027 million in Feb 2014 to the noninstitutional population of 247.085 million in Feb 2014 was 62.7 percent. The labor force of the US in Feb 2014 corresponding to 66.8 percent of participation in the population would be 165.053 million (0.668 x 247.085). The difference between the measured labor force in Feb 2014 of 155.027 million and the labor force in Feb 2014 with participation rate of 66.8 percent (as in Jul 2007) of 165.053 million is 10.026 million. The level of the labor force in the US has stagnated and is 10.026 million lower than what it would have been had the same participation rate been maintained. Millions of people have abandoned their search for employment because they believe there are no jobs available for them. The key issue is whether the decline in participation of the population in the labor force is the result of people giving up on finding another job.

Chart I-3, US, Civilian Labor Force, Thousands, SA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

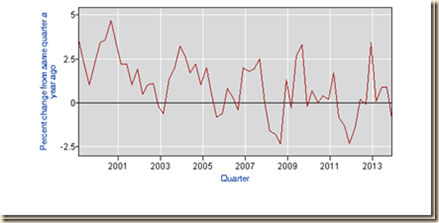

Chart I-4 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides 12-month percentage changes of the level of the labor force in the US. The rate of growth fell almost instantaneously with the global recession and became negative from 2009 to 2011. The labor force of the US collapsed and did not recover. Growth in the beginning of the summer originates in younger people looking for jobs in the summer after graduation or during school recess.

Chart I-4, US, Civilian Labor Force, Thousands, NSA, 12-month Percentage Change, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

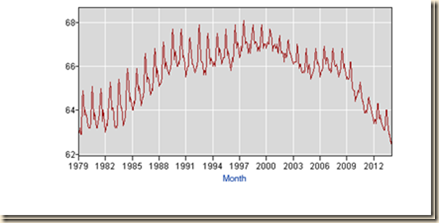

Chart I-5 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the labor force participation rate in the US or labor force as percent of the population. The labor force participation rate of the US fell from 66.8 percent in Jan 2001 to 62.7 percent NSA in Feb 2014, all numbers not seasonally adjusted. The annual labor force participation rate for 1979 was 63.7 percent and also 63.7 percent in Nov 1980 during sharp economic contraction. This comparison is further elaborated below. Chart I-5 shows an evident downward trend beginning with the global recession that has continued throughout the recovery beginning in IIIQ2009. The critical issue is whether people left the workforce of the US because they believe there is no longer a job for them.

Chart I-5, Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate, Percent of Population in Labor Force SA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

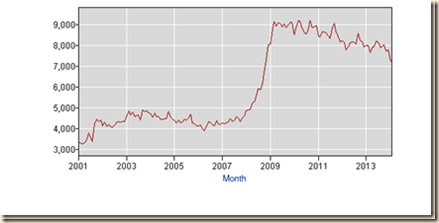

Chart I-6 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the level of unemployed in the US. The number unemployed rose from the trough of 6.272 million NSA in Oct 2006 to the peak of 16.147 million in Jan 2010, declining to 13.400 million in Jul 2012, 12.696 million in Aug 2012 and 11.741 million in Sep 2012. The level unemployed fell to 11.741 million in Oct 2012, 11.404 million in Nov 2012, 11.844 million in Dec 2012, 13.181 million in Jan 2013, 12.500 million in Feb 2013 and 9.984 million in Dec 2013. The level of unemployment reached 10.893 million in Feb 2014, all numbers not seasonally adjusted.

Chart I-6, US, Unemployed, Thousands, SA, 2001-2014

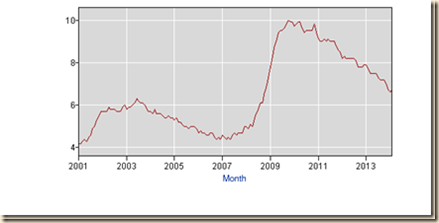

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

Chart I-7 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the rate of unemployment in the US or unemployed as percent of the labor force. The rate of unemployment of the US rose from 4.7 percent in Jan 2001 to 6.5 percent in Jun 2003, declining to 4.1 percent in Oct 2006. The rate of unemployment jumped to 10.6 percent in Jan 2010 and declined to 7.6 percent in Dec 2012 but increased to 8.5 percent in Jan 2013 and 8.1 percent in Feb 2013, falling back to 7.3 percent in Apr 2013 and 7.8 percent in Jun 2013, all numbers not seasonally adjusted. The rate of unemployment not seasonally adjusted stabilized at 7.7 percent in Jul 2013 and fell to 6.5 percent in Dec 2013 and 7.0 percent in Feb 2014.

Chart I-7, US, Unemployment Rate, SA, 2001-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-8 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides 12-month percentage changes of the level of unemployed. There was a jump of 81.8 percent in Apr 2009 with subsequent decline and negative rates since 2010. On an annual basis, the level of unemployed rose 59.8 percent in 2009 and 26.1 percent in 2008 with increase of 3.9 percent in 2010, decline of 7.3 percent in 2011 and decrease of 9.0 percent in 2012. The annual rate of unemployment decreased 8.4 percent in 2013 and fell 12.9 percent in Feb 2014 relative to Feb 2013.

Chart I-8, US, Unemployed, 12-month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

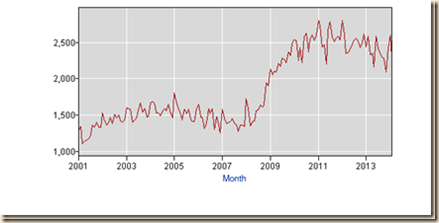

Chart I-9 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the number of people in part-time occupations because of economic reasons, that is, because they cannot find full-time employment. The number underemployed in part-time occupations not seasonally adjusted rose from 3.732 million in Jan 2001 to 5.270 million in Jan 2004, falling to 3.787 million in Apr 2006. The number underemployed seasonally adjusted jumped to 9.114 million in Nov 2009, falling to 8.177 million in Dec 2011 but increasing to 8.228 million in Jan 2012 and 8.133 million in Feb 2012 but then falling to 7.929 million in Dec 2012 and increasing to 8.180 million in Jul 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons seasonally adjusted reached 7.771 million in Dec 2013 and 7.186 million in Feb 2014. Without seasonal adjustment, the number employed part-time for economic reasons reached 9.354 million in Dec 2009, declining to 8.918 million in Jan 2012 and 8.166 million in Dec 2012 but increasing to 8.324 million in Jul 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons NSA stood at 7.990 million in Dec 2013 and 7.397 million in Feb 2014. The longer the period in part-time jobs the lower are the chances of finding another full-time job.

Chart I-9, US, Part-Time for Economic Reasons, Thousands, SA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

Chart I-10 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics repeats the behavior of unemployment. The 12-month percentage change of the level of people at work part-time for economic reasons jumped 84.7 percent in Mar 2009 and declined subsequently. The declines have been insufficient to reduce significantly the number of people who cannot shift from part-time to full-time employment. On an annual basis, the number of part-time for economic reasons increased 33.5 percent in 2008 and 51.7 percent in 2009, declining 0.4 percent in 2010, 3.5 percent in 2011 and 5.1 percent in 2012. The annual number of part-time for economic reasons decreased 2.3 percent in 2013. The number of part-time for economic reasons fell 10.9 percent in Feb 2014 relative to a year earlier.

Chart I-10, US, Part-Time for Economic Reasons NSA 12-Month Percentage Change, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

Chart II-11 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the same pattern of the number marginally attached to the labor force jumping to significantly higher levels during the global recession and remaining at historically high levels. The number marginally attached to the labor force not seasonally adjusted increased from 1.295 million in Jan 2001 to 1.691 million in Feb 2004. The number of marginally attached to the labor force fell to 1.299 million in Sep 2006 and increased to 2.609 million in Dec 2010 and 2.800 million in Jan 2011. The number marginally attached to the labor force was 2.540 million in Dec 2011, increasing to 2.809 million in Jan 2012, falling to 2.608 million in Feb 2012. The number marginally attached to the labor force fell to 2.352 million in Mar 2012, 2.363 million in Apr 2012, 2.423 million in May 2012, 2.483 million in Jun 2012, 2.529 million in Jul 2012 and 2.561 million in Aug 2012. The number marginally attached to the labor force fell to 2.517 million in Sep 2012, 2.433 million in Oct 2012, 2.505 million in Nov 2012 and 2.427 million in in Dec 2013. The number marginally attached to the labor force reached 2.303 million in Feb 2014.

Chart I-11, US, Marginally Attached to the Labor Force, Thousands, NSA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

Chart I-12 provides 12-month percentage changes of the marginally attached to the labor force from 2001 to 2014. There was a jump of 56.1 percent in May 2009 during the global recession followed by declines in percentage changes but insufficient negative changes. On an annual basis, the number of marginally attached to the labor force increased in four consecutive years: 15.7 percent in 2008, 37.9 percent in 2009, 11.7 percent in 2010 and 3.5 percent in 2011. The number marginally attached to the labor force fell 2.2 percent on annual basis in 2012 but increased 2.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2012, fell 13.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan 2013, falling 10.7 percent in the 12 months ending in May 2013. The number marginally attached to the labor force increased 4.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2013 and fell 4.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Jul 2013 and 8.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug 2013. The annual number of marginally attached to the labor force fell 6.2 percent in 2013. The number marginally attached to the labor force fell 7.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 and 11.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb 2014.

Chart I-12, US, Marginally Attached to the Labor Force 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/data/

Table I-4 consists of data and additional calculations using the BLS household survey, illustrating the possibility that the actual rate of unemployment could be 11.9 percent and the number of people in job stress could be around 29.1 million, which is 17.8 percent of the effective labor force. The first column provides for 2006 the yearly average population (POP), labor force (LF), participation rate or labor force as percent of population (PART %), employment (EMP), employment population ratio (EMP/POP %), unemployment (UEM), the unemployment rate as percent of labor force (UEM/LF Rate %) and the number of people not in the labor force (NLF). All data are unadjusted or not-seasonally-adjusted (NSA). The numbers in column 2006 are averages in millions while the monthly numbers for Feb 2013, Jan 2014 and Feb 2014 are in thousands, not seasonally adjusted. The average yearly participation rate of the population in the labor force was in the range of 66.0 percent minimum to 67.1 percent maximum between 2000 and 2006 with the average of 66.4 percent (ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/lf/aa2006/pdf/cpsaat1.pdf). Table I-4b provides the yearly labor force participation rate from 1979 to 2014. The objective of Table I-4 is to assess how many people could have left the labor force because they do not think they can find another job. Row “LF PART 66.2 %” applies the participation rate of 2006, almost equal to the rates for 2000 to 2006, to the noninstitutional civilian population in Feb 2013, Jan 2014 and Feb 2014 to obtain what would be the labor force of the US if the participation rate had not changed. In fact, the participation rate fell to 63.2 percent by Feb 2013 and was 62.5 percent in Jan 2014 and 62.7 percent in Feb 2014, suggesting that many people simply gave up on finding another job. Row “∆ NLF UEM” calculates the number of people not counted in the labor force because they could have given up on finding another job by subtracting from the labor force with participation rate of 66.2 percent (row “LF PART 66.2%”) the labor force estimated in the household survey (row “LF”). Total unemployed (row “Total UEM”) is obtained by adding unemployed in row “∆NLF UEM” to the unemployed of the household survey in row “UEM.” The row “Total UEM%” is the effective total unemployed “Total UEM” as percent of the effective labor force in row “LF PART 66.2%.” The results are that:

- there are an estimated 8.543 million unemployed in Jan 2014 who are not counted because they left the labor force on their belief they could not find another job (∆NLF UEM), that is, they dropped out of their job searches

- the total number of unemployed is effectively 19.436 million (Total UEM) and not 10.893 million (UEM) of whom many have been unemployed long term

- the rate of unemployment is 11.9 percent (Total UEM%) and not 7.0 percent, not seasonally adjusted, or 6.7 percent seasonally adjusted

- the number of people in job stress is close to 29.1 million by adding the 8.543 million leaving the labor force because they believe they could not find another job.

The row “In Job Stress” in Table I-4 provides the number of people in job stress not seasonally adjusted at 29.136 million in Feb 2014, adding the total number of unemployed (“Total UEM”), plus those involuntarily in part-time jobs because they cannot find anything else (“Part Time Economic Reasons”) and the marginally attached to the labor force (“Marginally attached to LF”). The final row of Table I-4 shows that the number of people in job stress is equivalent to 17.8 percent of the labor force in Feb 2014. The employment population ratio “EMP/POP %” dropped from 62.9 percent on average in 2006 to 58.1 percent in Feb 2013, 58.1 percent in Jan 2014 and 58.3 percent in Feb 2014. The number employed in Feb 2014 was 144.134 million (NSA) or 3.181 million fewer people with jobs relative to the peak of 147.315 million in Jul 2007 while the civilian noninstitutional population increased from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 247.085 million in Feb 2014 or by 15.127 million. The number employed fell 2.2 percent from Jul 2007 to Feb 2014 while population increased 6.5 percent. There is actually not sufficient job creation in merely absorbing new entrants in the labor force because of those dropping from job searches, worsening the stock of unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs.

What really matters for labor input in production and wellbeing is the number of people with jobs or the employment/population ratio, which has declined and does not show signs of increasing. There are several million fewer people working in 2014 than in 2006 and the number employed is not increasing while population increased 15.127 million. The argument that anemic population growth causes “secular stagnation” in the US (Hansen 1938, 1939, 1941) is as misplaced currently as in the late 1930s (for early dissent see Simons 1942). There is currently population growth in the ages of 16 to 24 years but not enough job creation and discouragement of job searches for all ages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.htm). This is merely another case of theory without reality with dubious policy proposals. The number of hiring relative to the number unemployed measures the chances of becoming employed. The number of hiring in the US economy has declined by 17 million and does not show signs of increasing in an unusual recovery without hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.htm). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth on trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,107.4 billion than actual $15,932.9 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than on trend, explaining the 29.1 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 17.8 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html). US GDP grew from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,932.9 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.2 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 29.1 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 17.8 percent of the effective labor force (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline.

Table I-4, US, Population, Labor Force and Unemployment, NSA

| 2006 | Feb 2013 | Jan 2014 | Feb 2014 | |

| POP | 229 | 244.828 | 246,915 | 247,085 |

| LF | 151 | 154,727 | 154,381 | 155,027 |

| PART% | 66.2 | 63.2 | 62.5 | 62.7 |

| EMP | 144 | 142,228 | 143,526 | 144,134 |

| EMP/POP% | 62.9 | 58.1 | 58.1 | 58.3 |

| UEM | 7 | 12,500 | 10,855 | 10,893 |

| UEM/LF Rate% | 4.6 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| NLF | 77 | 90,100 | 92,534 | 92,058 |

| LF PART 66.2% | 162,076 | 163,458 | 163,570 | |

| ∆NLF UEM | 7,349 | 9,077 | 8,543 | |

| Total UEM | 19,849 | 19,932 | 19,436 | |

| Total UEM% | 12.2 | 12.2 | 11.9 | |

| Part Time Economic Reasons | 8,298 | 7,771 | 7,397 | |

| Marginally Attached to LF | 2,588 | 2,592 | 2,303 | |

| In Job Stress | 30,735 | 30,295 | 29,136 | |

| People in Job Stress as % Labor Force | 19.0 | 18.5 | 17.8 |

Pop: population; LF: labor force; PART: participation; EMP: employed; UEM: unemployed; NLF: not in labor force; ∆NLF UEM: additional unemployed; Total UEM is UEM + ∆NLF UEM; Total UEM% is Total UEM as percent of LF PART 66.2%; In Job Stress = Total UEM + Part Time Economic Reasons + Marginally Attached to LF

Note: the first column for 2006 is in average millions; the remaining columns are in thousands; NSA: not seasonally adjusted

The labor force participation rate of 66.2% in 2006 is applied to current population to obtain LF PART 66.2%; ∆NLF UEM is obtained by subtracting the labor force with participation of 66.2 percent from the household survey labor force LF; Total UEM is household data unemployment plus ∆NLF UEM; and total UEM% is total UEM divided by LF PART 66.2%

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

In the analysis of Hansen (1939, 3) of secular stagnation, economic progress consists of growth of real income per person driven by growth of productivity. The “constituent elements” of economic progress are “(a) inventions, (b) the discovery and development of new territory and new resources, and (c) the growth of population” (Hansen 1939, 3). Secular stagnation originates in decline of population growth and discouragement of inventions. According to Hansen (1939, 2), US population grew by 16 million in the 1920s but grew by one half or about 8 million in the 1930s with forecasts at the time of Hansen’s writing in 1938 of growth of around 5.3 million in the 1940s. Hansen (1939, 2) characterized demography in the US as “a drastic decline in the rate of population growth. Hansen’s plea was to adapt economic policy to stagnation of population in ensuring full employment. In the analysis of Hansen (1939, 8), population caused half of the growth of US GDP per year. Growth of output per person in the US and Europe was caused by “changes in techniques and to the exploitation of new natural resources.” In this analysis, population caused 60 percent of the growth of capital formation in the US. Declining population growth would reduce growth of capital formation. Residential construction provided an important share of growth of capital formation. Hansen (1939, 12) argues that market power of imperfect competition discourages innovation with prolonged use of obsolete capital equipment. Trade unions would oppose labor-savings innovations. The combination of stagnating and aging population with reduced innovation caused secular stagnation. Hansen (1939, 12) concludes that there is role for public investments to compensate for lack of dynamism of private investment but with tough tax/debt issues.

The current application of Hansen’s (1938, 1939, 1941) proposition argues that secular stagnation occurs because full employment equilibrium can be attained only with negative real interest rates between minus 2 and minus 3 percent. Professor Lawrence H. Summers (2013Nov8) finds that “a set of older ideas that went under the phrase secular stagnation are not profoundly important in understanding Japan’s experience in the 1990s and may not be without relevance to America’s experience today” (emphasis added). Summers (2013Nov8) argues there could be an explanation in “that the short-term real interest rate that was consistent with full employment had fallen to -2% or -3% sometime in the middle of the last decade. Then, even with artificial stimulus to demand coming from all this financial imprudence, you wouldn’t see any excess demand. And even with a relative resumption of normal credit conditions, you’d have a lot of difficulty getting back to full employment.” The US economy could be in a situation where negative real rates of interest with fed funds rates close to zero as determined by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) do not move the economy to full employment or full utilization of productive resources. Summers (2013Oct8) finds need of new thinking on “how we manage an economy in which the zero nominal interest rates is a chronic and systemic inhibitor of economy activity holding our economies back to their potential.”

Former US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin (2014Jan8) finds three major risks in prolonged unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing: (1) incentive of delaying action by political leaders; (2) “financial moral hazard” in inducing excessive exposures pursuing higher yields of risker credit classes; and (3) major risks in exiting unconventional policy. Rubin (2014Jan8) proposes reduction of deficits by structural reforms that could promote recovery by improving confidence of business attained with sound fiscal discipline.

Professor John B. Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) provides clear thought on the lack of relevance of Hansen’s contention of secular stagnation to current economic conditions. The application of secular stagnation argues that the economy of the US has attained full-employment equilibrium since around 2000 only with negative real rates of interest of minus 2 to minus 3 percent. At low levels of inflation, the so-called full-employment equilibrium of negative interest rates of minus 2 to minus 3 percent cannot be attained and the economy stagnates. Taylor (2014Jan01) analyzes multiple contradictions with current reality in this application of the theory of secular stagnation:

- Secular stagnation would predict idle capacity, in particular in residential investment when fed fund rates were fixed at 1 percent from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004. Taylor (2014Jan01) finds unemployment at 4.4 percent with house prices jumping 7 percent from 2002 to 2003 and 14 percent from 2004 to 2005 before dropping from 2006 to 2007. GDP prices doubled from 1.7 percent to 3.4 percent when interest rates were low from 2003 to 2005.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) finds another contradiction in the application of secular stagnation based on low interest rates because of savings glut and lack of investment opportunities. Taylor (2009) shows that there was no savings glut. The savings rate of the US in the past decade is significantly lower than in the 1980s.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) finds another contradiction in the low ratio of investment to GDP currently and reduced investment and hiring by US business firms.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) argues that the financial crisis and global recession were caused by weak implementation of existing regulation and departure from rules-based policies.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) argues that the recovery from the global recession was constrained by a change in the regime of regulation and fiscal/monetary policies.

In revealing research, Edward P. Lazear and James R. Spletzer (2012JHJul22) use the wealth of data in the valuable database and resources of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (http://www.bls.gov/data/) in providing clear thought on the nature of the current labor market of the United States. The critical issue of analysis and policy currently is whether unemployment is structural or cyclical. Structural unemployment could occur because of (1) industrial and demographic shifts and (2) mismatches of skills and job vacancies in industries and locations. Consider the aggregate unemployment rate, Y, expressed in terms of share si of a demographic group in an industry i and unemployment rate yi of that demographic group (Lazear and Spletzer 2012JHJul22, 5-6):

Y = ∑isiyi (1)

This equation can be decomposed for analysis as (Lazear and Spletzer 2012JHJul22, 6):

∆Y = ∑i∆siy*i + ∑i∆yis*i (2)

The first term in (2) captures changes in the demographic and industrial composition of the economy ∆si multiplied by the average rate of unemployment y*i , or structural factors. The second term in (2) captures changes in the unemployment rate specific to a group, or ∆yi, multiplied by the average share of the group s*i, or cyclical factors. There are also mismatches in skills and locations relative to available job vacancies. A simple observation by Lazear and Spletzer (2012JHJul22) casts intuitive doubt on structural factors: the rate of unemployment jumped from 4.4 percent in the spring of 2007 to 10 percent in October 2009. By nature, structural factors should be permanent or occur over relative long periods. The revealing result of the exhaustive research of Lazear and Spletzer (2012JHJul22) is:

“The analysis in this paper and in others that we review do not provide any compelling evidence that there have been changes in the structure of the labor market that are capable of explaining the pattern of persistently high unemployment rates. The evidence points to primarily cyclic factors.”

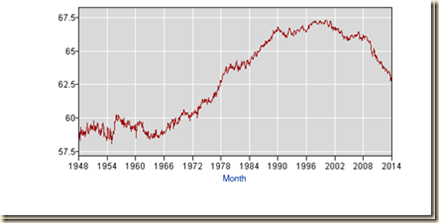

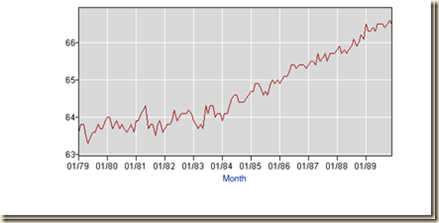

Table I-4b and Chart I-12-b provide the US labor force participation rate or percentage of the labor force in population. It is not likely that simple demographic trends caused the sharp decline during the global recession and failure to recover earlier levels. The civilian labor force participation rate dropped from the peak of 66.9 percent in Jul 2006 to 62.6 percent in Dec 2013 and 62.7 percent in Feb 2014. The civilian labor force participation rate was 63.7 percent on an annual basis in 1979 and 63.4 percent in Dec 1980 and Dec 1981, reaching even 62.9 percent in both Apr and May 1979. The civilian labor force participation rate jumped with the recovery to 64.8 percent on an annual basis in 1985 and 65.9 percent in Jul 1985. Structural factors cannot explain these sudden changes vividly shown visually in the final segment of Chart I-12b. Seniors would like to delay their retiring especially because of the adversities of financial repression on their savings. Labor force statistics are capturing the disillusion of potential workers with their chances in finding a job in what Lazear and Spletzer (2012JHJul22) characterize as accentuated cyclical factors. The argument that anemic population growth causes “secular stagnation” in the US (Hansen 1938, 1939, 1941) is as misplaced currently as in the late 1930s (for early dissent see Simons 1942). There is currently population growth in the ages of 16 to 24 years but not enough job creation and discouragement of job searches for all ages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html). “Secular stagnation” would be a process over many years and not from one year to another. This is merely another case of theory without reality with dubious policy proposals.

Table I-4b, US, Labor Force Participation Rate, Percent of Labor Force in Population, NSA, 1979-2014

| Year | Jan | Feb | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annual |

| 1979 | 62.9 | 63.0 | 64.9 | 64.5 | 63.8 | 64.0 | 63.8 | 63.8 | 63.7 |

| 1980 | 63.3 | 63.2 | 65.1 | 64.5 | 63.6 | 63.9 | 63.7 | 63.4 | 63.8 |

| 1981 | 63.2 | 63.2 | 65.0 | 64.6 | 63.5 | 64.0 | 63.8 | 63.4 | 63.9 |

| 1982 | 63.0 | 63.2 | 65.3 | 64.9 | 64.0 | 64.1 | 64.1 | 63.8 | 64.0 |

| 1983 | 63.3 | 63.2 | 65.4 | 65.1 | 64.3 | 64.1 | 64.1 | 63.8 | 64.0 |

| 1984 | 63.3 | 63.4 | 65.9 | 65.2 | 64.4 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.3 | 64.4 |

| 1985 | 64.0 | 64.0 | 65.9 | 65.4 | 64.9 | 65.1 | 64.9 | 64.6 | 64.8 |

| 1986 | 64.2 | 64.4 | 66.6 | 66.1 | 65.3 | 65.5 | 65.4 | 65.0 | 65.3 |

| 1987 | 64.7 | 64.8 | 66.8 | 66.5 | 65.5 | 65.9 | 65.7 | 65.5 | 65.6 |

| 1988 | 65.1 | 65.2 | 67.1 | 66.8 | 65.9 | 66.1 | 66.2 | 65.9 | 65.9 |

| 1989 | 65.8 | 65.6 | 67.7 | 67.2 | 66.3 | 66.6 | 66.7 | 66.3 | 66.5 |

| 1990 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 67.7 | 67.1 | 66.4 | 66.5 | 66.3 | 66.1 | 66.5 |

| 1991 | 65.5 | 65.7 | 67.3 | 66.6 | 66.1 | 66.1 | 66.0 | 65.8 | 66.2 |

| 1992 | 65.7 | 65.8 | 67.9 | 67.2 | 66.3 | 66.2 | 66.2 | 66.1 | 66.4 |

| 1993 | 65.6 | 65.8 | 67.5 | 67.0 | 66.1 | 66.4 | 66.3 | 66.2 | 66.3 |

| 1994 | 66.0 | 66.2 | 67.5 | 67.2 | 66.5 | 66.8 | 66.7 | 66.5 | 66.6 |

| 1995 | 66.1 | 66.2 | 67.7 | 67.1 | 66.5 | 66.7 | 66.5 | 66.2 | 66.6 |

| 1996 | 65.8 | 66.1 | 67.9 | 67.2 | 66.8 | 67.1 | 67.0 | 66.7 | 66.8 |

| 1997 | 66.4 | 66.5 | 68.1 | 67.6 | 67.0 | 67.1 | 67.1 | 67.0 | 67.1 |

| 1998 | 66.6 | 66.7 | 67.9 | 67.3 | 67.0 | 67.1 | 67.1 | 67.0 | 67.1 |

| 1999 | 66.7 | 66.8 | 67.9 | 67.3 | 66.8 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 67.1 |

| 2000 | 66.8 | 67.0 | 67.6 | 67.2 | 66.7 | 66.9 | 66.9 | 67.0 | 67.1 |

| 2001 | 66.8 | 66.8 | 67.4 | 66.8 | 66.6 | 66.7 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 66.8 |

| 2002 | 66.2 | 66.6 | 67.2 | 66.8 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 66.3 | 66.2 | 66.6 |

| 2003 | 66.1 | 66.2 | 66.8 | 66.3 | 65.9 | 66.1 | 66.1 | 65.8 | 66.2 |

| 2004 | 65.7 | 65.7 | 66.8 | 66.2 | 65.7 | 66.0 | 66.1 | 65.8 | 66.0 |

| 2005 | 65.4 | 65.6 | 66.8 | 66.5 | 66.1 | 66.2 | 66.1 | 65.9 | 66.0 |

| 2006 | 65.5 | 65.7 | 66.9 | 66.5 | 66.1 | 66.4 | 66.4 | 66.3 | 66.2 |

| 2007 | 65.9 | 65.8 | 66.8 | 66.1 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 66.1 | 65.9 | 66.0 |

| 2008 | 65.7 | 65.5 | 66.8 | 66.4 | 65.9 | 66.1 | 65.8 | 65.7 | 66.0 |

| 2009 | 65.4 | 65.5 | 66.2 | 65.6 | 65.0 | 64.9 | 64.9 | 64.4 | 65.4 |

| 2010 | 64.6 | 64.6 | 65.3 | 65.0 | 64.6 | 64.4 | 64.4 | 64.1 | 64.7 |

| 2011 | 63.9 | 63.9 | 64.6 | 64.3 | 64.2 | 64.1 | 63.9 | 63.8 | 64.1 |

| 2012 | 63.4 | 63.6 | 64.3 | 63.7 | 63.6 | 63.8 | 63.5 | 63.4 | 63.7 |

| 2013 | 63.3 | 63.2 | 64.0 | 63.4 | 63.2 | 62.9 | 62.9 | 62.6 | 63.2 |

| 2014 | 62.5 | 62.7 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-12b, US, Labor Force Participation Rate, Percent of Labor Force in Population, NSA, 1979-2014

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

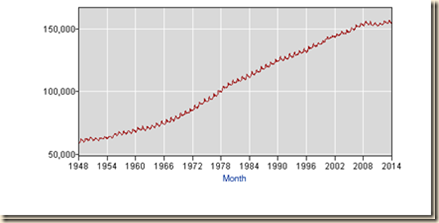

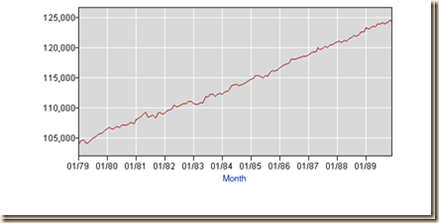

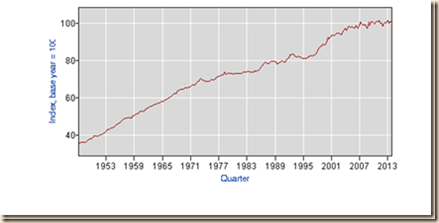

Broader perspective is provided by Chart I-12c of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The United States civilian noninstitutional population has increased along a consistent trend since 1948 that continued through earlier recessions and the global recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 and the cyclical expansion after IIIQ2009.

Chart I-12c, US, Civilian Noninstitutional Population, Thousands, NSA, 1948-2014

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

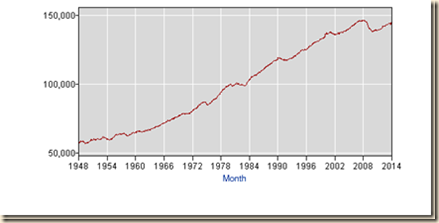

The labor force of the United States in Chart I-12d has increased along a trend similar to that of the civilian noninstitutional population in Chart I-12c. There is an evident stagnation of the civilian labor force in the final segment of Chart I-12d during the current economic cycle. This stagnation is explained by cyclical factors similar to those analyzed by Lazear and Spletzer (2012JHJul22) that motivated an increasing population to drop out of the labor force instead of structural factors. Large segments of the potential labor force are not observed, constituting unobserved unemployment and of more permanent nature because those afflicted have been seriously discouraged from working by the lack of opportunities.

Chart I-12d, US, Labor Force, Thousands, NSA, 1948-2014

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

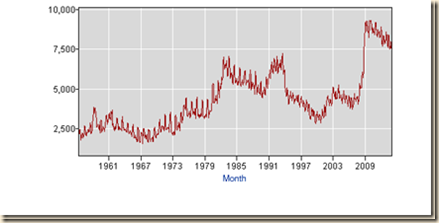

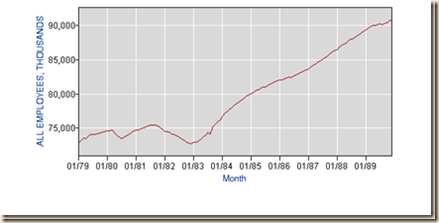

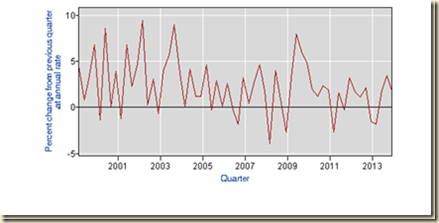

IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment. There is initial discussion here of long-term employment trends followed by cyclical comparison. Growth and employment creation have been mediocre in the expansion beginning in Jul IIIQ2009 from the contraction between Dec IVQ2007 and Jun IIQ2009 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). A series of charts from the database of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides significant insight. Chart I-13 provides the monthly employment level of the US from 1948 to 2014. The number of people employed has trebled. There are multiple contractions throughout the more than six decades but followed by resumption of the strong upward trend. The contraction after 2007 is deeper and followed by a flatter curve of job creation. The United States missed this opportunity of high growth in the initial phase of recovery that historically eliminated unemployment and underemployment created during the contraction. Inferior performance of the US economy and labor markets is the critical current issue of analysis and policy design. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.3 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the second estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp4q13_2nd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth on trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,107.4 billion than actual $15,932.9 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than on trend, explaining the 29.1 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 17.8 percent of the effective labor force (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html). US GDP grew from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,932.9 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.2 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Chart I-13, US, Employment Level, Thousands, SA, 1948-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The steep and consistent curve of growth of the US labor force is shown in Chart I-14. The contraction beginning in Dec 2007 flattened the path of the US civilian labor force and is now followed by a flatter curve during the current expansion.

Chart I-14, US, Civilian Labor Force, SA, 1948-2014, Thousands

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-15 for the period from 1948 to 2014. The labor force participation rate is influenced by numerous factors such as the age of the population. There is no comparable episode in the postwar economy to the sharp collapse of the labor force participation rate in Chart I-15 during the contraction and subsequent expansion after 2007. Aging can reduce the labor force participation rate as many people retire but many may have decided to work longer as their wealth and savings have been significantly reduced. There is an important effect of many people just exiting the labor force because they believe there is no job available for them.

Chart I-15, US, Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate, SA, 1948-2014, %

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

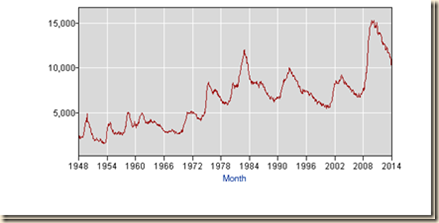

The number of unemployed in the US jumped seasonally adjusted from 5.8 million in May 1979 to 12.1 million in Dec 1982, by 6.3 million, or 108.6 percent. The jump not seasonally adjusted was from 5.4 million in May 1979 to 12.5 million in Jan 1983, by 7.1 million or 131.5 percent. The number of unemployed seasonally adjusted jumped from 6.7 million in Mar 2007 to 15.4 million in Oct 2009, by 8.7 million, or 129.9 percent. The number of unemployed not seasonally adjusted jumped from 6.5 million in Apr 2007 to 16.1 million in Jan 2010, by 9.6 million or 147.7 percent. These are the two episodes with steepest increase in the level of unemployment in Chart I-16.

Chart I-16, US, Unemployed, SA, 1948-2014, Thousands

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

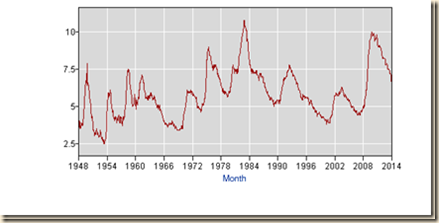

Chart I-17 provides the rate of unemployment of the US from 1948 to 2014. The peak of the series is 10.8 percent in both Nov and Dec 1982. The second highest rates are 10.0 percent in Oct 2009 and 9.9 percent in both Nov and Dec 2009. The unadjusted rate of unemployment reached 10.6 percent in Jan 2010.

Chart I-17, US, Unemployment Rate, SA, 1948-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-18 provides the number unemployed for 27 weeks and over from 1948 to 2013. The number unemployed for 27 weeks and over jumped from 510,000 in Dec 1978 to 2.885 million in Jun 1983, by 2.4 million, or 465.7 percent. The number of unemployed 27 weeks or over jumped from 1.132 million in May 2007 to 6.604 million in Jun 2010, by 5.472 million, or 483.4 percent.

Chart I-18, US, Unemployed for 27 Weeks or More, SA, 1948-2014, Thousands

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The employment-population ratio in Chart I-19 is an important indicator of wellbeing in labor markets, measuring the number of people with jobs. The US employment-population ratio fell from 63.5 in Dec 2006 to 58.6 in Jul 2011 and stands at 58.3 NSA in Feb 2014. There is no comparable decline followed by stabilization during an expansion in Chart I-19.

Chart I-19, US, Employment-Population Ratio, 1948-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The number employed part-time for economic reasons in Chart I-20 increased in the recessions and declined during the expansions. In the current cycle, the number employed part-time for economic reasons increased sharply and has not returned to normal levels. Lower growth of economic activity in the expansion after IIIQ2009 failed to reduce the number desiring to work full time but finding only part-time occupations.

Chart I-20, US, Part-Time for Economic Reasons, NSA, 1955-2014, Thousands

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-5 provides percentage change of real GDP in the United States in the 1930s, 1980s and 2000s. The recession in 1981-1982 is quite similar on its own to the 2007-2009 recession. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.4 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Data are available for the 1930s only on a yearly basis. US GDP fell 4.7 percent in the two recessions (1) from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and (2) from III1981 to IVQ1981 to IVQ1982 and 4.3 percent cumulatively in the recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. It is instructive to compare the first three years of the expansions in the 1980s and the current expansion. GDP grew at 4.6 percent in 1983, 7.3 percent in 1984, 4.2 percent in 1985 and 3.5 percent in 1986 while GDP grew, 2.5 percent in 2010, 1.8 percent in 2011, 2.8 percent in 2012 and 1.9 percent in 2013. Actual annual equivalent GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012 and first four quarters of 2013 is 2.3 percent and 2.7 percent in the four quarters of 2013 but only 2.3 percent discounting contribution of 1.67 percentage points of inventory accumulation to growth in IIIQ2013. GDP grew at 4.2 percent in 1985 and 3.5 percent in 1986 while the forecasts of the central tendency of participants of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are in the range of 2.2 to 2.3 percent in 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf) with less reliable forecast of 2.8 to 3.2 percent in 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf). Growth of GDP in the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2013 has been at average 2.3 percent in annual equivalent.

Table I-5, US, Percentage Change of GDP in the 1930s, 1980s and 2000s, ∆%

| Year | GDP ∆% | Year | GDP ∆% | Year | GDP ∆% |

| 1930 | -8.5 | 1980 | -0.2 | 2000 | 4.1 |

| 1931 | -6.4 | 1981 | 2.6 | 2001 | 1.0 |

| 1932 | -12.9 | 1982 | -1.9 | 2002 | 1.8 |

| 1933 | -1.3 | 1983 | 4.6 | 2003 | 2.8 |

| 1934 | 10.8 | 1984 | 7.3 | 2004 | 3.8 |

| 1935 | 8.9 | 1985 | 4.2 | 2005 | 3.4 |

| 1936 | 12.9 | 1986 | 3.5 | 2006 | 2.7 |

| 1937 | 5.1 | 1987 | 3.5 | 2007 | 1.8 |

| 1938 | -3.3 | 1988 | 4.2 | 2008 | -0.3 |

| 1930 | 8.0 | 1989 | 3.7 | 2009 | -2.8 |

| 1940 | 8.8 | 1990 | 1.9 | 2010 | 2.5 |

| 1941 | 17.7 | 1991 | -0.1 | 2011 | 1.8 |

| 1942 | 18.9 | 1992 | 3.6 | 2012 | 2.8 |

| 1943 | 17.0 | 1993 | 2.7 | 2013 | 1.9 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Characteristics of the four cyclical contractions are provided in Table I-6 with the first column showing the number of quarters of contraction; the second column the cumulative percentage contraction; and the final column the average quarterly rate of contraction. There were two contractions from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and from IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 separated by three quarters of expansion. The drop of output combining the declines in these two contractions is 4.7 percent, which is almost equal to the decline of 4.3 percent in the contraction from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.4 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is entirely misleading.

Table I-6, US, Number of Quarters, GDP Cumulative Percentage Contraction and Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate in Cyclical Contractions

| Number of Quarters | Cumulative Percentage Contraction | Average Percentage Rate | |

| IIQ1953 to IIQ1954 | 3 | -2.4 | -0.8 |

| IIIQ1957 to IIQ1958 | 3 | -3.0 | -1.0 |

| IVQ1973 to IQ1975 | 5 | -3.1 | -0.6 |

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 | 2 | -2.2 | -1.1 |

| IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | 4 | -2.5 | -0.64 |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | 6 | -4.3 | -0.72 |

Sources: Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table I-7 shows the mediocre average annual equivalent growth rate of 2.3 percent of the US economy in the eighteen quarters of the current cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2013. In sharp contrast, the average growth rate of GDP was: 5.7 percent in the first thirteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986, 5.4 percent in the first fifteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent in the first sixteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent in the first seventeen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and 5.0 percent in the eighteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIQ1987. The line “average first four quarters in four expansions” provides the average growth rate of 7.7 percent with 7.8 percent from IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955, 9.2 percent from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959, 6.1 percent from IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 and 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The United States missed this opportunity of high growth in the initial phase of recovery. BEA data show the US economy in standstill with annual growth of 2.4 percent in 2010 decelerating to 1.8 percent annual growth in 2011 and 2.8 percent in 2012 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) The expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012 and 2013 accumulated to 4.5 percent that is equivalent to 2.2 percent in a year. This is obtained by dividing GDP in IVQ2013 of $15,932.9 billion by GDP in IVQ2011 of $15,242.1 billion and compounding by 4/8: {[($15,932.9/$15,242.1)4/8 -1]100 = 2.2%}. The US economy grew 2.5 percent in IVQ2013 relative to the same quarter a year earlier in IVQ2012. Another important revelation of the revisions and enhancements is that GDP was flat in IVQ2012, which is just at the borderline of contraction. The rate of growth of GDP in the third estimate of IIIQ2013 is 4.1 percent in seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR). Inventory accumulation contributed 1.67 percentage points to this rate of growth. The actual rate without this impulse of unsold inventories would have been 2.43 percent, or 0.6 percent in IIIQ2013, such that annual equivalent growth in 2013 is closer to 2.1 percent {[(1.003)(1.006)(1.006)(1.0064/4-1]100 = 2.1%}, compounding the quarterly rates and converting into annual equivalent.

Table I-7, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Growth and Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate in Cyclical Expansions

| Number | Cumulative Growth ∆% | Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate | |

| IIIQ 1954 to IQ1957 | 11 | 12.8 | 4.5 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| IIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 5 | 10.0 | 7.9 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 4 | 9.2 | |

| IIQ1975 to IVQ1976 | 8 | 8.3 | 4.1 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 | 4 | 6.1 | |

| IQ1983-IQ1986 IQ1983-IIIQ1986 IQ1983-IVQ1986 IQ1983-IQ1987 IQ1983-IIQ1987 | 13 15 16 17 18 | 19.9 21.6 22.3 23.1 24.5 | 5.7 5.4 5.2 5.0 5.0 |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| Average First Four Quarters in Four Expansions* | 7.7 | ||

| IIIQ2009 to IVQ2013 | 18 | 11.0 | 2.3 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 |

*First Four Quarters: 7.8% IIIQ1954-IIQ1955; 9.2% IIIQ1958-IIQ1959; 6.1% IIIQ1975-IIQ1976; 7.8% IQ1983-IVQ1983

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

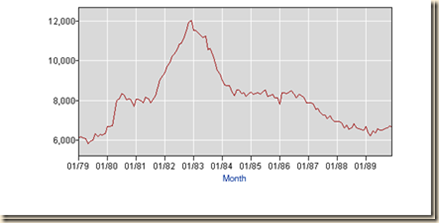

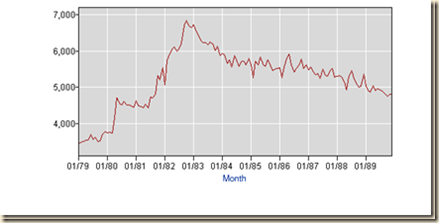

A group of charts from the database of the Bureau of Labor Statistics facilitate the comparison of employment in the 1980s and 2000s. The long-term charts and tables from I-5 to I-7 in the discussion above confirm the view that the comparison of the current expansion should be with that in the 1980s because of similar dimensions. Chart I-21 provides the level of employment in the US between 1979 and 1989. Employment surged after the contraction and grew rapidly during the decade.

Chart I-21, US, Employed, Thousands, 1979-1989

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics