Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth, Stagnating Real Disposable Income, Destruction of Household Wealth for Inflation Adjusted Loss, United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities, Housing Collapse, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013

Executive Summary

I Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IA2 Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits

IB Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

IIA Destruction of Household Wealth for Inflation Adjusted Loss

IIB United States Housing Collapse

IIC United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IIC1 Transmission of Monetary Policy

IIC2 Functions of Banks

IIC3 United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IIC4 Theory and Reality of Economic History and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

Executive Summary

Contents of Executive Summary

ESI Increasing Interest Rate Risk, Tapering Quantitative Easing, Duration Dumping, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk

ESII Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

ESIII Weakness of Growth in Expansion

ESIV Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

ESV Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits

ESVI Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

ESVII Financial Repression

ESVIII Destruction of Household Wealth for Inflation Adjusted Loss

ESIX United States Housing Collapse

ESX United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

ESI Increasing Interest Rate Risk, Tapering Quantitative Easing, Duration Dumping, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task for both theory and measurement. The IMF (2012WEOOct) provides surveillance of the world economy with its Global Economic Outlook (WEO) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/index.htm), of the world financial system with its Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) (IMF 2012GFSROct) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2012/02/index.htm) and of fiscal affairs with the Fiscal Monitor (IMF 2012FMOct) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2012/02/fmindex.htm). There appears to be a moment of transition in global economic and financial variables that may prove of difficult analysis and measurement. It is useful to consider a summary of global economic and financial risks, which are analyzed in detail in the comments of this blog in Section VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets, Table VI-4.

Economic risks include the following:

- China’s Economic Growth. China is lowering its growth target to 7.5 percent per year. China’s GDP growth decelerated significantly from annual equivalent 10.4 percent in IIQ2011 to 7.4 percent in IVQ2011 and 6.2 percent in IQ2012, rebounding to 8.7 percent in IIQ2012, 8.2 percent in IIIQ2012 and 7.8 percent in IVQ2012. Annual equivalent growth in IQ2013 fell to 6.6 percent and to 7.0 percent in IIQ2013 (See Subsection VC and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/tapering-quantitative-easing-policy-and_7005.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/recovery-without-hiring-world-inflation.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/10/world-inflation-waves-stagnating-united_21.html).

- United States Economic Growth, Labor Markets and Budget/Debt Quagmire. The US is growing slowly with 28.3 million in job stress, fewer 10 million full-time jobs, high youth unemployment, historically low hiring and declining/stagnating real wages.

- Economic Growth and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies. Advanced economies are growing slowly. There is still high unemployment in advanced economies.

- World Inflation Waves. Inflation continues in repetitive waves globally (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html).

A list of financial uncertainties includes:

- Euro Area Survival Risk. The resilience of the euro to fiscal and financial doubts on larger member countries is still an unknown risk.

- Foreign Exchange Wars. Exchange rate struggles continue as zero interest rates in advanced economies induce devaluation of their currencies.

- Valuation of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with lower volumes.

- Duration Trap of the Zero Bound. The yield of the US 10-year Treasury rose from 2.031 percent on Mar 9, 2012, to 2.294 percent on Mar 16, 2012. Considering a 10-year Treasury with coupon of 2.625 percent and maturity in exactly 10 years, the price would fall from 105.3512 corresponding to yield of 2.031 percent to 102.9428 corresponding to yield of 2.294 percent, for loss in a week of 2.3 percent but far more in a position with leverage of 10:1. Min Zeng, writing on “Treasurys fall, ending brutal quarter,” published on Mar 30, 2012, in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303816504577313400029412564.html?mod=WSJ_hps_sections_markets), informs that Treasury bonds maturing in more than 20 years lost 5.52 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

- Credibility and Commitment of Central Bank Policy. There is a credibility issue of the commitment of monetary policy (Sargent and Silber 2012Mar20).

- Carry Trades. Commodity prices driven by zero interest rates have resumed their increasing path with fluctuations caused by intermittent risk aversion

Professionals use a variety of techniques in measuring interest rate risk (Fabozzi, Buestow and Johnson, 2006, Chapter Nine, 183-226):

- Full valuation approach in which securities and portfolios are shocked by 50, 100, 200 and 300 basis points to measure their impact on asset values

- Stress tests requiring more complex analysis and translation of possible events with high impact even if with low probability of occurrence into effects on actual positions and capital

- Value at Risk (VaR) analysis of maximum losses that are likely in a time horizon

- Duration and convexity that are short-hand convenient measurement of changes in prices resulting from changes in yield captured by duration and convexity

- Yield volatility

Analysis of these methods is in Pelaez and Pelaez (International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-162) and Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the States, Vol. (I) (2008a), 78-100). Frederick R. Macaulay (1938) introduced the concept of duration in contrast with maturity for analyzing bonds. Duration is the sensitivity of bond prices to changes in yields. In economic jargon, duration is the yield elasticity of bond price to changes in yield, or the percentage change in price after a percentage change in yield, typically expressed as the change in price resulting from change of 100 basis points in yield. The mathematical formula is the negative of the yield elasticity of the bond price or –[dB/d(1+y)]((1+y)/B), where d is the derivative operator of calculus, B the bond price, y the yield and the elasticity does not have dimension (Hallerbach 2001). The duration trap of unconventional monetary policy is that duration is higher the lower the coupon and higher the lower the yield, other things being constant. Coupons and yields are historically low because of unconventional monetary policy. Duration dumping during a rate increase may trigger the same crossfire selling of high duration positions that magnified the credit crisis. Traders reduced positions because capital losses in one segment, such as mortgage-backed securities, triggered haircuts and margin increases that reduced capital available for positioning in all segments, causing fire sales in multiple segments (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2008b), 217-24). Financial markets are currently experiencing fear of duration resulting from the debate within and outside the Fed on tapering quantitative easing. Table VIII-2 provides the yield curve of Treasury securities on Sep 27, 2013, Sep 5, 2013, May 1, 2013, Sep 27, 2012 and Sep 27, 2006. There is ongoing steepening of the yield curve for longer maturities, which are also the ones with highest duration. The 10-year yield increased from 1.45 percent on Jul 26, 2012 to 2.98 percent on Sep 5, 2013, as measured by the United States Treasury. Assume that a bond with maturity in 10 years were issued on Sep 5, 2013 at par or price of 100 with coupon of 1.45 percent. The price of that bond would be 86.8530 with instantaneous increase of the yield to 2.98 percent for loss of 13.1 percent and far more with leverage. Losses absorb capital available for positioning, triggering crossfire sales in multiple asset classes (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009). Chris Dieterich, writing on “Bond investors turn to cash,” on Jul 25, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323971204578625900935618178.html), uses data of the Investment Company Institute (http://www.ici.org/) in showing withdrawals of $43 billion in taxable mutual funds in Jun, which is the largest in history, with flows into cash investments such as $8.5 billion in the week of Jul 17 into money-market funds.

Table VIII-2, United States, Treasury Yields

| 9/27/13 | 9/05/13 | 5/01/13 | 9/27/12 | 9/27/06 | |

| 1 M | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 4.60 |

| 3 M | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 4.88 |

| 6 M | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 5.01 |

| 1 Y | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 4.89 |

| 2 Y | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 4.66 |

| 3 Y | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 4.59 |

| 5 Y | 1.40 | 1.85 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 4.56 |

| 7 Y | 2.02 | 2.45 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 4.56 |

| 10 Y | 2.64 | 2.98 | 1.66 | 1.66 | 4.60 |

| 20 Y | 3.40 | 3.64 | 2.44 | 2.43 | 4.81 |

| 30 Y | 3.68 | 3.88 | 2.83 | 2.83 | 4.73 |

Source: United States Treasury http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/Pages/index.aspx

Interest rate risk is increasing in the US. Chart VI-13 of the Board of Governors provides the conventional mortgage rate for a fixed-rate 30-year mortgage. The rate stood at 5.87 percent on Jan 8, 2004, increasing to 6.79 percent on Jul 6, 2006. The rate bottomed at 3.35 percent on May 2, 2013. Fear of duration risk in longer maturities such as mortgage-backed securities caused continuing increases in the conventional mortgage rate that rose to 4.51 percent on Jul 11, 2013 and 4.32 percent on Sep 26, 2013, which is the last data point in Chart VI-13.

Chart VI-13, US, Conventional Mortgage Rate, Jan 8, 2004 to Sep 19, 2013

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/update/

The major reason and channel of transmission of unconventional monetary policy is through expectations of inflation. Fisher (1930) provided theoretical and historical relation of interest rates and inflation. Let in be the nominal interest rate, ir the real or inflation-adjusted interest rate and πe the expectation of inflation in the time term of the interest rate, which are all expressed as proportions. The following expression provides the relation of real and nominal interest rates and the expectation of inflation:

(1 + ir) = (1 + in)/(1 + πe) (1)

That is, the real interest rate equals the nominal interest rate discounted by the expectation of inflation in time term of the interest rate. Fisher (1933) analyzed the devastating effect of deflation on debts. Nominal debt contracts remained at original principal interest but net worth and income of debtors contracted during deflation. Real interest rates increase during declining inflation. For example, if the interest rate is 3 percent and prices decline 0.2 percent, equation (1) calculates the real interest rate as:

(1 +0.03)/(1 – 0.02) = 1.03/(0.998) = 1.032

That is, the real rate of interest is (1.032 – 1) 100 or 3.2 percent. If inflation were 2 percent, the real rate of interest would be 0.98 percent, or about 1.0 percent {[(1.03/1.02) -1]100 = 0.98%}.

The yield of the one-year Treasury security was quoted in the Wall Street Journal at 0.114 percent on Fri May 17, 2013 (http://online.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_topnav_marketdata_main). The expected rate of inflation πe in the next twelve months is not observed. Assume that it would be equal to the rate of inflation in the past twelve months estimated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BLS) at 1.1 percent (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/). The real rate of interest would be obtained as follows:

(1 + 0.00114)/(1 + 0.011) = (1 + rr) = 0.9902

That is, ir is equal to 1 – 0.9902 or minus 0.98 percent. Investing in a one-year Treasury security results in a loss of 0.98 percent relative to inflation. The objective of unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates is to induce consumption and investment because of the loss to inflation of riskless financial assets. Policy would be truly irresponsible if it intended to increase inflationary expectations or πe. The result could be the same rate of unemployment with higher inflation (Kydland and Prescott 1977).

Current focus is on tapering quantitative easing by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). There is sharp distinction between the two measures of unconventional monetary policy: (1) fixing of the overnight rate of fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent; and (2) outright purchase of Treasury and agency securities and mortgage-backed securities for the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. Market are overreacting to the so-called “paring” of outright purchases of $85 billion of securities per month for the balance sheet of the Fed. What is truly important is the fixing of the overnight fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent for which there is no end in sight as evident in the FOMC statement for Sep 18, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130918a.htm):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored” (emphasis added).

There is a critical phrase in the statement of Sep 19, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130918a.htm): “but mortgage rates have risen further.” Did the increase of mortgage rates influence the decision of the FOMC not to taper? Is FOMC “communication” and “guidance” successful?

In delivering the biannual report on monetary policy (Board of Governors 2013Jul17), Chairman Bernanke (2013Jul17) advised Congress that:

“Instead, we are providing additional policy accommodation through two distinct yet complementary policy tools. The first tool is expanding the Federal Reserve's portfolio of longer-term Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS); we are currently purchasing $40 billion per month in agency MBS and $45 billion per month in Treasuries. We are using asset purchases and the resulting expansion of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet primarily to increase the near-term momentum of the economy, with the specific goal of achieving a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market in a context of price stability. We have made some progress toward this goal, and, with inflation subdued, we intend to continue our purchases until a substantial improvement in the labor market outlook has been realized. We are relying on near-zero short-term interest rates, together with our forward guidance that rates will continue to be exceptionally low--our second tool--to help maintain a high degree of monetary accommodation for an extended period after asset purchases end, even as the economic recovery strengthens and unemployment declines toward more-normal levels. In appropriate combination, these two tools can provide the high level of policy accommodation needed to promote a stronger economic recovery with price stability.

The Committee's decisions regarding the asset purchase program (and the overall stance of monetary policy) depend on our assessment of the economic outlook and of the cumulative progress toward our objectives. Of course, economic forecasts must be revised when new information arrives and are thus necessarily provisional.”

Friedman (1953) argues there are three lags in effects of monetary policy: (1) between the need for action and recognition of the need; (2) the recognition of the need and taking of actions; and (3) taking of action and actual effects. Friedman (1953) finds that the combination of these lags with insufficient knowledge of the current and future behavior of the economy causes discretionary economic policy to increase instability of the economy or standard deviations of real income σy and prices σp. Policy attempts to circumvent the lags by policy impulses based on forecasts. We are all naïve about forecasting. Data are available with lags and revised to maintain high standards of estimation. Policy simulation models estimate economic relations with structures prevailing before simulations of policy impulses such that parameters change as discovered by Lucas (1977). Economic agents adjust their behavior in ways that cause opposite results from those intended by optimal control policy as discovered by Kydland and Prescott (1977). Advance guidance attempts to circumvent expectations by economic agents that could reverse policy impulses but is of dubious effectiveness. There is strong case for using rules instead of discretionary authorities in monetary policy (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/search?q=rules+versus+authorities).

The key policy is maintaining fed funds rate between 0 and ¼ percent. An increase in fed funds rates could cause flight out of risk financial markets worldwide. There is no exit from this policy without major financial market repercussions. Indefinite financial repression induces carry trades with high leverage, risks and illiquidity.

A competing event is the high level of valuations of risk financial assets (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/peaking-valuation-of-risk-financial.html). Matt Jarzemsky, writing on Dow industrials set record,” on Mar 5, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324156204578275560657416332.html), analyzes that the DJIA broke the closing high of 14,164.53 set on Oct 9, 2007, and subsequently also broke the intraday high of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. The DJIA closed at 15,258.24

on Fri Sep 27, 2013, which is higher by 7.7 percent than the value of 14,164.53 reached on Oct 9, 2007 and higher by 7.5 percent than the value of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. Values of risk financial are approaching or exceeding historical highs.

Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Jobs upturn isn’t enough to satisfy Fed,” on Mar 8, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324582804578348293647760204.html), finds that much stronger labor market conditions are required for the Fed to end quantitative easing. Unconventional monetary policy with zero interest rates and quantitative easing is quite difficult to unwind because of the adverse effects of raising interest rates on valuations of risk financial assets and home prices, including the very own valuation of the securities held outright in the Fed balance sheet. Gradual unwinding of 1 percent fed funds rates from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004 by seventeen consecutive increases of 25 percentage points from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006 to reach 5.25 percent caused default of subprime mortgages and adjustable-rate mortgages linked to the overnight fed funds rate. The zero interest rate has penalized liquidity and increased risks by inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to speculative positions in risk financial assets. There is no exit from zero interest rates without provoking another financial crash.

The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets had proved strongest for commodity exposures but US equities have regained leadership. The DJIA has increased 57.5 percent since the trough of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe on Jul 2, 2010 to Sep 27, 2013; S&P 500 has gained 65.4 percent; and DAX 52.7 percent. Before the current round of risk aversion, almost all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 9/27/13” had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010 followed by negative performance but now some valuations of equity indexes show varying behavior: China’s Shanghai Composite is 9.4 percent below the trough; Japan’s Nikkei Average is 67.3 percent above the trough; DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 25.9 percent above the trough; Dow Global is 37.0 percent above the trough; STOXX 50 of 50 blue-chip European equities (http://www.stoxx.com/indices/index_information.html?symbol=sx5E) is 21.6 percent above the trough; and NYSE Financial Index is 41.4 percent above the trough. DJ UBS Commodities is 3.2 percent above the trough. DAX index of German equities (http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/DAX:IND) is 52.7 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 67.3 percent above the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 29.6 percent above the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 14,760.07 on Fri Sep 27, 2013 (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata), which is 43.9 percent higher than 10,254.43 on Mar 11, 2011, on the date of the Tōhoku or Great East Japan Earthquake/tsunami. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar depreciated by 13.4 percent relative to the euro and even higher before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 9/27/13” in Table VI-4 shows decrease of 1.5 percent in the week for China’s Shanghai Composite. DJ Asia Pacific increased 0.2 percent. NYSE Financial decreased 1.2 percent in the week. DJ UBS Commodities decreased 0.2 percent. Dow Global decreased 0.7 percent in the week of Sep 27, 2013. The DJIA decreased 1.2 percent and S&P 500 decreased 1.1 percent. DAX of Germany decreased 0.2 percent. STOXX 50 decreased 0.3 percent. The USD changed 0.0 percent. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks and banking soundness, US and world growth slowdown and China’s growth tradeoffs. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table VI-4 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 9/27/13” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Sep 27, 2013. Most risk financial assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 9/27/13” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 9/27/13.” There are now several equity indexes above the peak in Table VI-4: DJIA 36.2 percent, S&P 500 39.0 percent, DAX 36.8 percent, Dow Global 11.8 percent, DJ Asia Pacific 10.2 percent, NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) 12.6 percent, Nikkei Average 29.6 percent and STOXX 50 2.9 percent. There is only one equity index below the peak: Shanghai Composite by 31.8 percent. DJ UBS Commodities Index is now 11.7 percent below the peak. The US dollar strengthened 10.6 percent relative to the peak. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr 2010 is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul 2010 because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. Alexandra Scaggs, writing on “Tepid profits, roaring stocks,” on May 16, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323398204578487460105747412.html), analyzes stabilization of earnings growth: 70 percent of 458 reporting companies in the S&P 500 stock index reported earnings above forecasts but sales fell 0.2 percent relative to forecasts of increase of 0.5 percent. Paul Vigna, writing on “Earnings are a margin story but for how long,” on May 17, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/05/17/earnings-are-a-margin-story-but-for-how-long/), analyzes that corporate profits increase with stagnating sales while companies manage costs tightly. More than 90 percent of S&P components reported moderate increase of earnings of 3.7 percent in IQ2013 relative to IQ2012 with decline of sales of 0.2 percent. Earnings and sales have been in declining trend. In IVQ2009, growth of earnings reached 104 percent and sales jumped 13 percent. Net margins reached 8.92 percent in IQ2013, which is almost the same at 8.95 percent in IIIQ2006. Operating margins are 9.58 percent. There is concern by market participants that reversion of margins to the mean could exert pressure on earnings unless there is more accelerated growth of sales. Vigna (op. cit.) finds sales growth limited by weak economic growth. Kate Linebaugh, writing on “Falling revenue dings stocks,” on Oct 20, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444592704578066933466076070.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), identifies a key financial vulnerability: falling revenues across markets for United States reporting companies. Global economic slowdown is reducing corporate sales and squeezing corporate strategies. Linebaugh quotes data from Thomson Reuters that 100 companies of the S&P 500 index have reported declining revenue only 1 percent higher in Jun-Sep 2012 relative to Jun-Sep 2011 but about 60 percent of the companies are reporting lower sales than expected by analysts with expectation that revenue for the S&P 500 will be lower in Jun-Sep 2012 for the entities represented in the index. Results of US companies are likely repeated worldwide. Future company cash flows derive from investment projects. In IQ1980, gross private domestic investment in the US was $951.6 billion of 2009 dollars, growing to $1,143.0 billion in IVQ1986 or 20.1 percent. Real gross private domestic investment in the US decreased 3.1 percent from $2,605.2 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,524.9 billion in IIQ2013. Real private fixed investment fell 4.9 percent from $2,586.3 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,458.4 billion in IIQ2013. Growth of real private investment in is mediocre for all but four quarters from IIQ2011 to IQ2012 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html). The investment decision of United States corporations has been fractured in the current economic cycle in preference of cash. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA fell $26.6 billion in IQ2013 after increasing $34.9 billion in IVQ2012 and $13.9 billion in IIIQ2012. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA rebounded with $66.8 billion in IIQ2013. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA fell $1.7 billion in IQ2013 after increasing $40.8 billion in IVQ2012 and $4.5 billion in IIIQ2012. In IIQ2013, profits after tax with IVA and CCA increased $56.9 billion. Anticipation of higher taxes in the “fiscal cliff” episode caused increase of $120.9 billion in net dividends in IVQ2012 followed with adjustment in the form of decrease of net dividends by $103.8 billion in IQ2013, rebounding with $273.5 billion in IIQ2013. There is similar decrease of $80.1 billion in undistributed profits with IVA and CCA in IVQ2012 followed by increase of $102.1 billion in IQ2013 and decline of $216.6 billion in IIQ2013. Undistributed profits of US corporations swelled 263.4 percent from $107.7 billion IQ2007 to $391.4 billion in IIQ2013 and changed signs from minus $55.9 billion in billion in IVQ2007 (Section IA2). In IQ2013, corporate profits with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustment fell $26.6 billion relative to IVQ2012, from $2047.2 billion to $2020.6 billion at the quarterly rate of minus 1.3 percent. In IIQ2013, corporate profits with IVA and CCA increased $66.8 billion from $2020.6 billion in IQ2013 to $2087.4 billion at the quarterly rate of 3.3 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf). Uncertainty originating in fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy causes wide swings in expectations and decisions by the private sector with adverse effects on investment, real economic activity and employment. The investment decision of US business is fractured.

It may be quite painful to exit QE→∞ or use of the balance sheet of the central together with zero interest rates forever. The basic valuation equation that is also used in capital budgeting postulates that the value of stocks or of an investment project is given by:

Where Rτ is expected revenue in the time horizon from τ =1 to T; Cτ denotes costs; and ρ is an appropriate rate of discount. In words, the value today of a stock or investment project is the net revenue, or revenue less costs, in the investment period from τ =1 to T discounted to the present by an appropriate rate of discount. In the current weak economy, revenues have been increasing more slowly than anticipated in investment plans. An increase in interest rates would affect discount rates used in calculations of present value, resulting in frustration of investment decisions. If V represents value of the stock or investment project, as ρ → ∞, meaning that interest rates increase without bound, then V → 0, or

declines. Equally, decline in expected revenue from the stock or project, Rτ, causes decline in valuation. An intriguing issue is the difference in performance of valuations of risk financial assets and economic growth and employment. Paul A. Samuelson (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1970/samuelson-bio.html) popularized the view of the elusive relation between stock markets and economic activity in an often-quoted phrase “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” In the presence of zero interest rates forever, valuations of risk financial assets are likely to differ from the performance of the overall economy. The interrelations of financial and economic variables prove difficult to analyze and measure.

Table VI-4, Stock Indexes, Commodities, Dollar and 10-Year Treasury

| Peak | Trough | ∆% to Trough | ∆% Peak to 9/27/ /13 | ∆% Week 9/27/13 | ∆% Trough to 9/27/ 13 | |

| DJIA | 4/26/ | 7/2/10 | -13.6 | 36.2 | -1.2 | 57.5 |

| S&P 500 | 4/23/ | 7/20/ | -16.0 | 39.0 | -1.1 | 65.4 |

| NYSE Finance | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -20.3 | 12.6 | -1.2 | 41.4 |

| Dow Global | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -18.4 | 11.8 | -0.7 | 37.0 |

| Asia Pacific | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -12.5 | 10.2 | 0.2 | 25.9 |

| Japan Nikkei Aver. | 4/05/ | 8/31/ | -22.5 | 29.6 | 0.1 | 67.3 |

| China Shang. | 4/15/ | 7/02 | -24.7 | -31.8 | -1.5 | -9.4 |

| STOXX 50 | 4/15/10 | 7/2/10 | -15.3 | 2.9 | -0.3 | 21.6 |

| DAX | 4/26/ | 5/25/ | -10.5 | 36.8 | -0.2 | 52.7 |

| Dollar | 11/25 2009 | 6/7 | 21.2 | 10.6 | 0.0 | -13.4 |

| DJ UBS Comm. | 1/6/ | 7/2/10 | -14.5 | -11.7 | -0.2 | 3.2 |

| 10-Year T Note | 4/5/ | 4/6/10 | 3.986 | 2.784 | 2.626 |

T: trough; Dollar: positive sign appreciation relative to euro (less dollars paid per euro), negative sign depreciation relative to euro (more dollars paid per euro)

Source: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

ESII Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth. The US is experiencing the first expansion from a recession after World War II with disastrous socioeconomic conditions:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html)

- Private fixed investment declining 4.9 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2013 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html)

- Twenty eight million or 17.4 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (Section IB and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html)

- Twenty eight million unemployed or underemployed (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (Section IB and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html)

- 47 million in poverty and 48 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1995 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

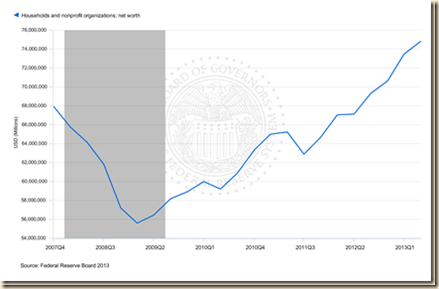

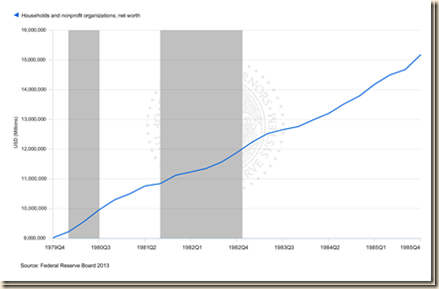

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations declining by 0.9 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2013 in contrast with growth at 3.0 percent in real terms from 1945 to 2012 (Section IIA and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/06/recovery-without-hiring-seven-million.html)

Valuations of risk financial assets approach historical highs. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.2 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 16 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_adv.pdf http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0613.pdf) and the second estimate of GDP for IIQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html). As a result, there are 28.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 17.4 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html).

The economy of the US can be summarized in growth of economic activity or GDP as decelerating from mediocre growth of 2.5 percent on an annual basis in 2010 to 1.8 percent in 2011 to 2.8 percent in 2012. The following calculations show that actual growth is around 1.4 to 1.8 percent per year. This rate is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which the economy of the US always attained for entire cycles in expansions after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May).

Revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_adv.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_2nd.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0713.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0813.pdf http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0613.pdf) provide important information on long-term growth and cyclical behavior. Table Summary provides relevant data.

- Long-term. US GDP grew at the average yearly rate of 3.3 percent from 1929 to 2012 and at 3.2 percent from 1947 to 2012. There were periodic contractions or recessions in this period but the economy grew at faster rates in the subsequent expansions, maintaining long-term economic growth at trend.

- Cycles. The combined contraction of GDP in the two almost consecutive recessions in the early 1980s is 4.7 percent. The contraction of US GDP from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 during the global recession was 4.3 percent. The critical difference in the expansion is growth at average 7.8 percent in annual equivalent in the first four quarters of recovery from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The average rate of growth of GDP in four cyclical expansions in the postwar period is 7.7 percent. In contrast, the rate of growth in the first four quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 was only 2.7 percent. Average annual equivalent growth in the expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986 was 5.7 percent. In contrast, average annual equivalent growth in the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013 was only 2.7 percent. The US appears to have lost its dynamism of income growth and employment creation.

Table Summary, Long-term and Cyclical Growth of GDP, Real Disposable Income and Real Disposable Income per Capita

| GDP | ||

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2012 | 3.3 | |

| 1947-2012 | 3.2 | |

| Cyclical Contractions ∆% | ||

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980, IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | -4.7 | |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | -4.3 | |

| Cyclical Expansions Average Annual Equivalent ∆% | ||

| IQ1983 to IQ1986 | 5.7 | |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 7.8 | |

| IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013 | 2.2 | |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 | |

| Real Disposable Income | Real Disposable Income per Capita | |

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2012 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| 1947-1999 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| Whole Cycles | ||

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| 2006-2012 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0813.pdf

The revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_adv.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_2nd.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0713.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0813.pdf http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0613.pdf) also provide critical information in assessing the current rhythm of US economic growth. The economy appears to be moving at a pace from 1.8 to 1.9 percent per year. Table Summary GDP provides the data.

1. Average Annual Growth in the Past Six Quarters. GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012 and the first two quarters of 2013 accumulated to 2.9 percent. This growth is equivalent to 1.9 percent per year, obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2013 of $15,679.7 by GDP in IVQ2011 of $15,242.1 and compounding by 4/6: {[($15,679.7/$15,242.1)4/6 -1]100 = 1.9.

2. Average Annual Growth in the First Two Quarters of 2013. GDP growth in the first two quarters of 2013 accumulated to 0.9 percent that is equivalent to 1.8 percent in a year. This is obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2013 of $15,679.7 by GDP in IVQ2012 of $15,539.6 and compounding by 4/2: {[($15,679.7/$15,539.6)4/2 -1]100 =1.8%}. The US economy grew 1.6 percent in IIQ2013 relative to the same quarter a year earlier in IIQ2012. Another important revelation of the revisions and enhancements is that GDP was flat in IVQ2012, which is just at the borderline of contraction.

Table Summary GDP, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 14,996.1 | NA | NA | 1.9 |

| IVQ2011 | 15,242.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| IQ2012 | 15,381.6 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| IIQ2012 | 15,427.7 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| IIIQ2012 | 15,534.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| IVQ2012 | 15,539.6 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| IQ2013 | 15,583.9 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| IIQ2013 | 15,679.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Cumulative ∆% IQ2012 to IIQ2013 | 2.9 | 2.8 | ||

| Annual Equivalent ∆% | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf

ESIII Weakness of Growth in Expansion. Characteristics of the four cyclical contractions are provided in Table I-4 with the first column showing the number of quarters of contraction; the second column the cumulative percentage contraction; and the final column the average quarterly rate of contraction. There were two contractions from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and from IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 separated by three quarters of expansion. The drop of output combining the declines in these two contractions is 4.7 percent, which is almost equal to the decline of 4.3 percent in the contraction from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.3 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is entirely misleading.

Table I-4, US, Number of Quarters, GDP Cumulative Percentage Contraction and Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate in Cyclical Contractions

| Number of Quarters | Cumulative Percentage Contraction | Average Percentage Rate | |

| IIQ1953 to IIQ1954 | 3 | -2.4 | -0.8 |

| IIIQ1957 to IIQ1958 | 3 | -3.0 | -1.0 |

| IVQ1973 to IQ1975 | 5 | -3.1 | -0.6 |

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 | 2 | -2.2 | -1.1 |

| IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | 4 | -2.5 | -0.64 |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | 6 | -4.3 | -0.72 |

Sources: Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm Reference Cycles National Bureau of Economic Research http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html

Cycles National Bureau of Economic Research http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html

Table I-5 shows the extraordinary contrast between the mediocre average annual equivalent growth rate of 2.2 percent of the US economy in the sixteen quarters of the current cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013 and the average of 5.7 percent in the first thirteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986, 5.3 percent in the first fifteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986 and 5.2 percent in the first sixteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1986. The line “average first four quarters in four expansions” provides the average growth rate of 7.7 percent with 7.8 percent from IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955, 9.2 percent from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959, 6.1 percent from IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 and 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The United States missed this opportunity of high growth in the initial phase of recovery. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). Table I-5 provides an average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions while the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 is only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates. As a result, there are 28.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 17.4 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html). BEA data show the US economy in standstill with annual growth of 2.4 percent in 2010 decelerating to 1.8 percent annual growth in 2011 and 2.8 percent in 2012 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. GDP growth in the first two quarters of 2013 accumulated to 0.9 percent that is equivalent to 1.8 percent in a year. This is obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2013 of $15,679.7 by GDP in IVQ2012 of $15,539.6 and compounding by 4/2: {[($15,679.7/$15,539.6)4/2 -1]100 =1.8%}. The US economy grew 1.6 percent in IIQ2013 relative to the same quarter a year earlier in IIQ2012. Another important revelation of the revisions and enhancements is that GDP was flat in IVQ2012, just at the borderline of contraction.

Table I-5, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Growth and Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate in Cyclical Expansions

| Number | Cumulative Growth ∆% | Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate | |

| IIIQ 1954 to IQ1957 | 11 | 12.8 | 4.5 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| IIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 5 | 10.0 | 7.9 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 4 | 9.2 | |

| IIQ1975 to IVQ1976 | 8 | 8.3 | 4.1 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 | 4 | 6.1 | |

| IQ1983 to IQ1986 IQ1983 to IIIQ1986 IQ1983 to IVQ1986 | 13 15 16 | 19.9 21.6 22.3 | 5.7 5.4 5.2 |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| Average First Four Quarters in Four Expansions* | 7.7 | ||

| IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013 | 16 | 9.2 | 2.2 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 |

*First Four Quarters: 7.8% IIIQ1954-IIQ1955; 9.2% IIIQ1958-IIQ1959; 6.1% IIIQ1975-IIQ1976; 7.8% IQ1983-IVQ1983

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm Reference Cycles National Bureau of Economic Research http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html

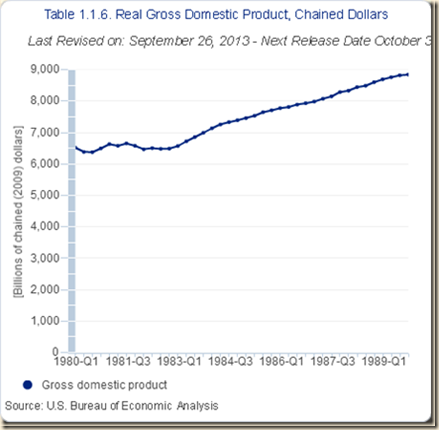

Chart I-8 shows US real quarterly GDP growth from 1980 to 1989. The economy contracted during the recession and then expanded vigorously throughout the 1980s, rapidly eliminating the unemployment caused by the contraction.

Chart I-8, US, Real GDP, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

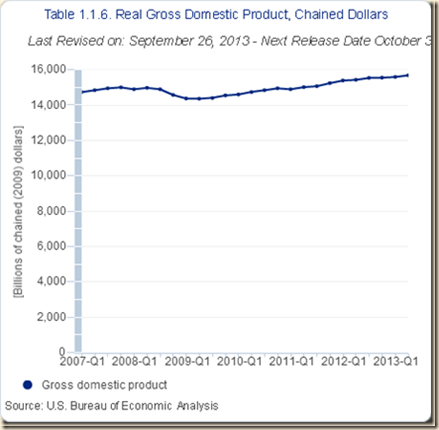

Chart I-9 shows the entirely different situation of real quarterly GDP in the US between 2007 and 2012. The economy has underperformed during the first sixteen quarters of expansion for the first time in the comparable contractions since the 1950s. The US economy is now in a perilous standstill.

Chart I-9, US, Real GDP, 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

As shown in Tables I-4 and I-5 above the loss of real GDP in the US during the contraction was 4.3 percent but the gain in the cyclical expansion has been only 9.2 percent (first to the last row in Table I-5), using all latest revisions. As a result, the level of real GDP in IIQ2013 with the second estimate and revisions is only higher by 4.6 percent than the level of real GDP in IVQ2007. Growth at trend of 3.0 percent in the entire cycle as in past cyclical expansions would result in GDP higher by 18.5 percent in IIQ2013 relative to IVQ2007. Trend GDP would be $17,770.4 billion, which is higher than actual GDP in IIQ2013 of $15,679.7 billion, for underperformance of $2,090.7 billion. Table I-6 provides in the second column real GDP in billions of chained 2005 dollars. The third column provides the percentage change of the quarter relative to IVQ2007; the fourth column provides the percentage change relative to the prior quarter; and the final fifth column provides the percentage change relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The contraction actually concentrated in two quarters: decline of 2.2 percent in IVQ2008 relative to the prior quarter and decline of 1.4 percent in IQ2009 relative to IVQ2008. The combined fall of GDP in IVQ2008 and IQ2009 was 3.6 percent {[(1-0.022) x (1-0.014) -1]100 = -3.6%}, or {[(IQ2009 $14,372.1)/(IIIQ2008 $14,895.1) – 1]100 = -3.5%} except for rounding. Those two quarters coincided with the worst effects of the financial crisis. GDP fell 0.1 percent in IIQ2009 but grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2009, which is the beginning of recovery in the cyclical dates of the NBER. Most of the recovery occurred in five successive quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2010 of growth of 1.0 percent in IVQ2009, 0.4 percent in IQ2010, 0.9 percent in IIQ2010 and equal growth at 0.7 percent in IIIQ2010 and 0.7 percent in IVQ2010 for cumulative growth in those five quarters of 3.8 percent, obtained by accumulating the quarterly rates {[(1.01 x 1.004 x 1.009 x 1.007 x 1.007) – 1]100 = 3.8%} or {[(IVQ2010 $14,942.4)/(IIIQ2009 $14,402.5) – 1]100 = 3.7%} with minor rounding difference. The economy then stalled during the first half of 2011 with decline of 0.3 percent in IQ2011 and growth of 0.8 percent in IIQ2011 for combined annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent {(0.997 x 1.008)2}. The economy grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2011 for annual equivalent growth of 1.1 percent in the first three quarters {[(0.997 x 1.008 x 1.003)4/3 -1]100 = 1.1%}. Growth picked up in IVQ2011 with 1.2 percent relative to IIIQ2011. Growth in a quarter relative to a year earlier in Table I-6 slows from over 2.7 percent during three consecutive quarters from IIQ2010 to IVQ2010 to 2.0 percent in IQ2011, 1.9 percent in IIQ2011, 1.5 percent in IIIQ2011 and 2.0 percent in IVQ2011. As shown below, growth of 1.2 percent in IVQ2011 was partly driven by inventory accumulation. In IQ2012, GDP grew 0.9 percent relative to IVQ2011 and 3.3 percent relative to IQ2011, decelerating to 0.3 percent in IIQ2012 and 2.8 percent relative to IIQ2011 and 0.7 percent in IIIQ2012 and 3.1 percent relative to IIIQ2011 largely because of inventory accumulation and national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.0 percent in IVQ2012 with 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier but mostly because of deduction of 2.00 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.22 percentage points of reduction of one-time national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.3 percent in IQ2013 and 1.3 percent relative to IQ2012 in large part because of burning savings to consume caused by financial repression of zero interest rates. There is similar growth of 0.6 percent in IIQ2013 and 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. Rates of a quarter relative to the prior quarter capture better deceleration of the economy than rates on a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The critical question for which there is not yet definitive solution is whether what lies ahead is continuing growth recession with the economy crawling and unemployment/underemployment at extremely high levels or another contraction or conventional recession. Forecasts of various sources continued to maintain high growth in 2011 without taking into consideration the continuous slowing of the economy in late 2010 and the first half of 2011. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro area is one of the common sources of doubts on the rate and direction of economic growth in the US but there is weak internal demand in the US with almost no investment and spikes of consumption driven by burning saving because of financial repression forever in the form of zero interest rates.

Table I-6, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2009 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 14,996.1 | NA | NA | 1.9 |

| IQ2008 | 14,895.4 | -0.7 | -0.7 | 1.1 |

| IIQ2008 | 14,969.2 | -0.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| IIIQ2008 | 14,895.1 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -0.3 |

| IVQ2008 | 14,574.6 | -2.8 | -2.2 | -2.8 |

| IQ2009 | 14,372.1 | -4.2 | -1.4 | -3.5 |

| IIQ2009 | 14,356.9 | -4.3 | -0.1 | -4.1 |

| IIIQ2009 | 14,402.5 | -4.0 | 0.3 | -3.3 |

| IV2009 | 14,540.2 | -3.0 | 1.0 | -0.2 |

| IQ2010 | 14,597.7 | -2.7 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| IIQ2010 | 14,738.0 | -1.7 | 0.9 | 2.7 |

| IIIQ2010 | 14,839.3 | -1.0 | 0.7 | 3.0 |

| IVQ2010 | 14,942.4 | -0.4 | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| IQ2011 | 14,894.0 | -0.7 | -0.3 | 2.0 |

| IIQ2011 | 15,011.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| IIIQ2011 | 15,062.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| IV2011 | 15,242.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| IQ2012 | 15,381.6 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| IIQ2012 | 15,427.7 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| IIIQ2012 | 15,534.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| IVQ2012 | 15,539.6 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| IQ2013 | 15,583.9 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| IIQ2013 | 15,679.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-10 provides the percentage change of real GDP from the same quarter a year earlier from 1980 to 1989. There were two contractions almost in succession in 1980 and from 1981 to 1983. The expansion was marked by initial high rates of growth as in other recession in the postwar US period during which employment lost in the contraction was recovered. Growth rates continued to be high after the initial phase of expansion.

Chart I-10, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

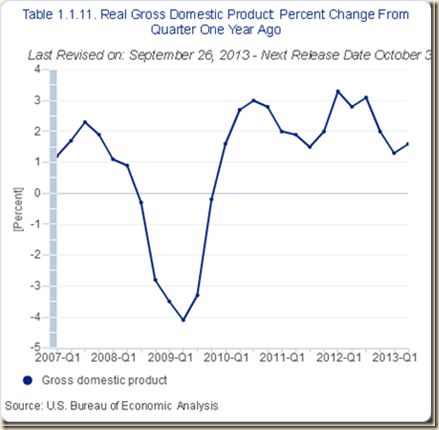

The experience of recovery after 2009 is not as complete as during the 1980s. Chart I-11 shows the much lower rates of growth in the early phase of the current expansion and sharp decline from an early peak. The US missed the initial high growth rates in cyclical expansions that eliminate unemployment and underemployment.

Chart I-11, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-12 provides growth rates from a quarter relative to the prior quarter during the 1980s. There is the same strong initial growth followed by a long period of sustained growth.

Chart I-12, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

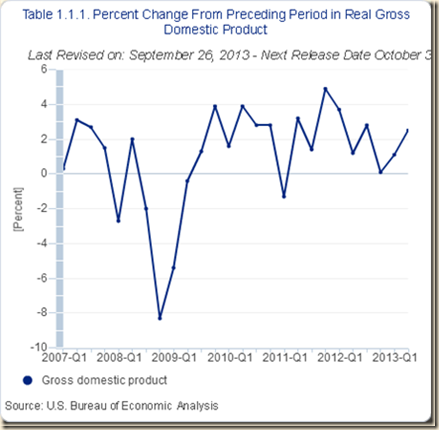

Chart I-13 provides growth rates in a quarter relative to the prior quarter from 2007 to 2013. Growth in the current expansion after IIIQ2009 has not been as strong as in other postwar cyclical expansions.

Chart I-13, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

ESIV Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment. The United States economy has grown at the average yearly rate of 3 percent per year and 2 percent per year in per capita terms from 1870 to 2010, as measured by Lucas (2011May). An important characteristic of the economic cycle in the US has been rapid growth in the initial phase of expansion after recessions.

Inferior performance of the US economy and labor markets is the critical current issue of analysis and policy design. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.2 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 16 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_adv.pdf http://bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0613.pdf) and the second estimate of GDP for IIQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp2q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk.html). As a result, there are 28.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 17.4 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html).

Table IA1-1 provides quarterly seasonally adjusted annual rates (SAAR) of growth of private fixed investment for the recessions of the 1980s and the current economic cycle. In the cyclical expansion beginning in IQ1983 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html), real private fixed investment in the United States grew at the average annual rate of 14.7 percent in the first eight quarters from IQ1983 to IVQ1984. Growth rates fell to an average of 2.2 percent in the following eight quarters from IQ1985 to IVQ1986. There were only two quarters of contraction of private fixed investment from IQ1983 to IVQ1986. There is quite different behavior of private fixed investment in the sixteen quarters of cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2013. The average annual growth rate in the first eight quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2011 was 3.3 percent, which is significantly lower than 14.7 percent in the first eight quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1984. There is only strong growth of private fixed investment in the four quarters of expansion from IIQ2011 to IQ2012 at the average annual rate of 10.5 percent. Growth has fallen from the SAAR of 14.8 percent in IIIQ2011 to 2.7 percent in IIIQ2012, recovering to 11.6 percent in IVQ2012 and falling to minus 1.5 percent in IQ2013. The SAAR of fixed investment rose to 6.5 percent in IIQ2013. Sudeep Reddy and Scott Thurm, writing on “Investment falls off a cliff,” on Nov 18, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324595904578123593211825394.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories) analyze the decline of private investment in the US and inform that a review by the Wall Street Journal of filing and conference calls finds that 40 of the largest publicly traded corporations in the US have announced intentions to reduce capital expenditures in 2012. The SAAR of real private fixed investment jumped to 11.6 percent in IVQ2012 but declined to minus 1.5 percent in IQ2013, recovering to 6.5 percent in IIQ2013.

Table IA1-1, US, Quarterly Growth Rates of Real Private Fixed Investment, % Annual Equivalent SA

| Q | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| I | 3.8 | -12.2 | 9.4 | 13.1 | -7.1 | -27.4 | 0.8 |

| II | 3.2 | -12.1 | 16.0 | 16.6 | -5.5 | -14.2 | 13.6 |

| III | 0.1 | -9.3 | 24.4 | 8.2 | -12.1 | -0.5 | -0.4 |

| IV | -1.5 | 0.2 | 24.3 | 7.3 | -23.9 | -2.8 | 8.5 |

| 1985 | 2011 | ||||||

| I | 3.7 | -0.5 | |||||

| II | 5.2 | 8.6 | |||||

| III | -1.6 | 14.8 | |||||

| IV | 7.8 | 10.0 | |||||

| 1986 | 2012 | ||||||

| I | 1.1 | 8.6 | |||||

| II | 0.1 | 4.7 | |||||

| III | -1.8 | 2.7 | |||||

| IV | 3.1 | 11.6 | |||||

| 1987 | 2013 | ||||||

| I | -6.7 | -1.5 | |||||

| II | 6.3 | 6.5 | |||||

| III | 7.1 | ||||||

| IV | -0.2 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IA1-1 of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides seasonally adjusted annual rates of growth of real private fixed investment from 1981 to 1986. Growth rates recovered sharply during the first eight quarters, which was essential in returning the economy to trend growth and eliminating unemployment and underemployment accumulated during the contractions.

Chart IA1-1, US, Real Private Fixed Investment, Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rates Percent Change from Prior Quarter, 1981-1986

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Weak behavior of real private fixed investment from 2007 to 2012 is shown in Chart IA1-2. Growth rates of real private fixed investment were much lower during the initial phase of expansion in the current economic cycle and have entered sharp trend of decline.

Chart IA1-2, US, Real Private Fixed Investment, Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rates Percent Change from Prior Quarter, 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IA1-2 provides real private fixed investment at seasonally adjusted annual rates from IVQ2007 to IIQ2013 or for the complete economic cycle. The first column provides the quarter, the second column percentage change relative to IVQ2007, the third column the quarter percentage change in the quarter relative to the prior quarter and the final column percentage change in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. In IQ1980, gross private domestic investment in the US was $951.6 billion of 2009 dollars, growing to $1,143.0 billion in IVQ1986 or 20.1 percent. Real gross private domestic investment in the US decreased 3.1 percent from $2,605.2 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,524.9 billion in IIQ2013. As shown in Table IAI-2, real private fixed investment fell 4.9 percent from $2,586.3 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,458.4 billion in IIQ2013. Growth of real private investment in Table IA1-2 is mediocre for all but four quarters from IIQ2011 to IQ2012.

Table IA1-2, US, Real Private Fixed Investment and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real PFI, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 2586.3 | NA | -1.2 | -1.4 |

| IQ2008 | 2539.1 | -1.8 | -1.8 | -3.0 |

| IIQ2008 | 2503.4 | -3.2 | -1.4 | -4.6 |

| IIIQ2008 | 2424.1 | -6.3 | -3.2 | -7.1 |

| IV2008 | 2263.8 | -12.5 | -6.6 | -12.5 |

| IQ2009 | 2089.3 | -19.2 | -7.7 | -17.7 |

| IIQ2009 | 2011.0 | -22.2 | -3.7 | -19.7 |

| IIIQ2009 | 2008.4 | -22.3 | -0.1 | -17.1 |

| IVQ2009 | 1994.1 | -22.9 | -0.7 | -11.9 |

| IQ2010 | 1997.9 | -22.8 | 0.2 | -4.4 |

| IIQ2010 | 2062.8 | -20.2 | 3.2 | 2.6 |

| IIIQ2010 | 2060.8 | -20.3 | -0.1 | 2.6 |

| IVQ2010 | 2103.1 | -18.7 | 2.1 | 5.5 |

| IQ2011 | 2100.7 | -18.8 | -0.1 | 5.1 |

| IIQ2011 | 2144.4 | -17.1 | 2.1 | 4.0 |

| IIIQ2011 | 2219.8 | -14.2 | 3.5 | 7.7 |

| IVQ2011 | 2273.4 | -12.1 | 2.4 | 8.1 |

| IQ2012 | 2320.8 | -10.3 | 2.1 | 10.5 |

| IIQ2012 | 2347.9 | -9.2 | 1.2 | 9.5 |

| IIIQ2012 | 2363.5 | -8.6 | 0.7 | 6.5 |

| IVQ2012 | 2429.1 | -6.1 | 2.8 | 6.8 |

| IQ2013 | 2420.0 | -6.4 | -0.4 | 4.3 |

| IIQ2013 | 2458.4 | -4.9 | 1.6 | 4.7 |

PFI: Private Fixed Investment

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IA1-3 provides real private fixed investment in billions of chained 2009 dollars from IV2007 to IIQ2013. Real private fixed investment has not recovered, stabilizing at a level in IIQ2013 that is 4.9 percent below the level in IVQ2007.

Chart IA1-3, US, Real Private Fixed Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars, IQ2007 to IIQ2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

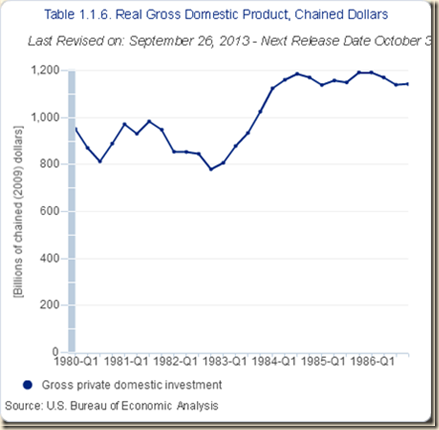

Chart IA1-4 provides real gross private domestic investment in chained dollars of 2009 from 1980 to 1986. Real gross private domestic investment climbed 20.1 percent to $1143.0 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ1986 above the level of $951.6 billion in IQ1980.

Chart IA1-4, US, Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars at Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, 1980-1986

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

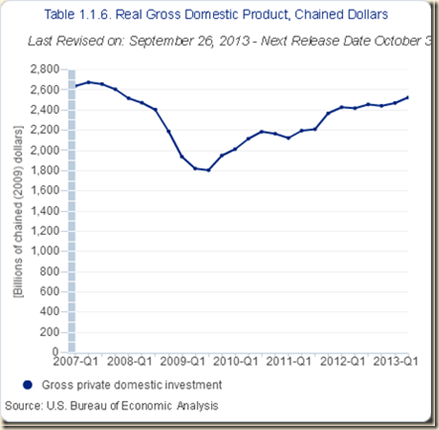

Chart IA1-5 provides real gross private domestic investment in the United States in billions of dollars of 2009 from 2006 to 2013. Gross private domestic investment reached a level of $2524.9 in IIQ2013 of that was 3.1 percent lower than the level of $2605.2 billion in IVQ2007 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm).

Chart IA1-5, US, Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars at Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, 2007-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

ESV Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits. Table IA1-5 provides value added of corporate business, dividends and corporate profits in billions of current dollars at seasonally adjusted annual rates (SAAR) in IVQ2007 and IIQ2013 together with percentage changes. The last three rows of Table IA1-5 provide gross value added of nonfinancial corporate business, consumption of fixed capital and net value added in billions of chained 2009 dollars at SAARs. Deductions from gross value added of corporate profits down the rows of Table IA1-5 end with undistributed corporate profits. Profits after taxes with inventory valuation adjustment (IVA) and capital consumption adjustment (CCA) increased by 100.0 percent in nominal terms from IVQ2007 to IIQ2013 while net dividends increased 26.9 percent and undistributed corporate profits swelled 263.4 percent from $107.7 billion in IQ2007 to $391.4 billion in IIQ2013 and changed signs from minus $55.9 billion in current dollars in IVQ2007. The investment decision of United States corporations has been fractured in the current economic cycle in preference of cash. Gross value added of nonfinancial corporate business adjusted for inflation increased 4.7 percent from IVQ2007 to IIQ2013, which is much lower than nominal increase of 15.3 percent in the same period for gross value added of total corporate business.

Table IA1-5, US, Value Added of Corporate Business, Corporate Profits and Dividends, IVQ2007-IQ2013

| IVQ2007 | IIQ2013 | ∆% | |

| Current Billions of Dollars Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates (SAAR) | |||

| Gross Value Added of Corporate Business | 8,165.9 | 9,414.0 | 15.3 |

| Consumption of Fixed Capital | 1,216.5 | 1,415.7 | 16.4 |

| Net Value Added | 6,949.4 | 7,998.3 | 15.1 |

| Compensation of Employees | 4,945.8 | 5,350.3 | 8.2 |

| Taxes on Production and Imports Less Subsidies | 688.5 | 752.1 | 9.2 |

| Net Operating Surplus | 1,315.1 | 1,895.9 | 44.2 |

| Net Interest and Misc | 204.2 | 113.4 | -44.5 |

| Business Current Transfer Payment Net | 68.9 | 98.2 | 42.5 |

| Corporate Profits with IVA and CCA Adjustments | 1,042.0 | 1,684.3 | 61.6 |

| Taxes on Corporate Income | 408.8 | 418.2 | 2.3 |

| Profits after Tax with IVA and CCA Adjustment | 633.2 | 1,266.1 | 100.0 |

| Net Dividends | 689.1 | 874.7 | 26.9 |

| Undistributed Profits with IVA and CCA Adjustment | -55.9 | 391.4 | NA |

| Billions of Chained USD 2009 SAAR | |||

| Gross Value Added of Nonfinancial Corporate Business | 7,519.3 | 7,873.6 | 4.7 |

| Consumption of Fixed Capital | 1,066.0 | 1,164.7 | 9.3 |

| Net Value Added | 6,453.4 | 6,708.9 | 4.0 |

IVA: Inventory Valuation Adjustment; CCA: Capital Consumption Adjustment

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IA1-6 provides comparable United States value added of corporate business, corporate profits and dividends from IQ1980 to IIIQ1986. There is significant difference both in nominal and inflation-adjusted data. Between IQ1980 and IIIQ1986, profits after tax with IVA and CCA increased 68.6 percent with dividends growing 110.0 percent and undistributed profits increasing 40.0 percent. There was much higher inflation in the 1980s than in the current cycle. For example, the consumer price index for all items not seasonally adjusted increased 37.9 percent between Mar 1980 and Dec 1986 but only 11.2 percent between Dec 2007 and Jun 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm). The comparison is still valid in terms of inflation-adjusted data: gross value added of nonfinancial corporate business adjusted for inflation increased 23.7 percent between IQ1980 and IIIQ1986 but only 4.6 percent between IVQ2007 and IIQ2013 while net value added adjusted for inflation increased 22.4 percent between IQ1980 and IIIQ1986 but only 4.0 percent between IVQ2007 and IIQ2013.

Table IA1-6, US, Value Added of Corporate Business, Corporate Profits and Dividends, IQ1980-IVQ1985

| IQ1980 | IIIQ1986 | ∆% | |

| Current Billions of Dollars Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates (SAAR) | |||

| Gross Value Added of Corporate Business | 1,654.1 | 2,713.5 | 64.0 |

| Consumption of Fixed Capital | 200.5 | 352.7 | 75.9 |

| Net Value Added | 1,453.6 | 2,360.9 | 62.4 |

| Compensation of Employees | 1,072.9 | 1,732.1 | 61.4 |

| Taxes on Production and Imports Less Subsidies | 121.5 | 220.9 | 81.8 |

| Net Operating Surplus | 259.2 | 408.0 | 57.4 |

| Net Interest and Misc. | 50.4 | 105.4 | 109.1 |

| Business Current Transfer Payment Net | 11.5 | 26.4 | 129.6 |

| Corporate Profits with IVA and CCA Adjustments | 197.2 | 276.2 | 40.1 |

| Taxes on Corporate Income | 97.0 | 107.3 | 10.6 |

| Profits after Tax with IVA and CCA Adjustment | 100.2 | 168.9 | 68.6 |

| Net Dividends | 40.9 | 85.9 | 110.0 |

| Undistributed Profits with IVA and CCA Adjustment | 59.3 | 83.0 | 40.0 |

| Billions of Chained USD 2009 SAAR | |||

| Gross Value Added of Nonfinancial Corporate Business | 2,952.3 | 3,651.9 | 23.7 |

| Consumption of Fixed Capital | 315.6 | 423.6 | 34.2 |

| Net Value Added | 2,636.7 | 3,228.3 | 22.4 |

IVA: Inventory Valuation Adjustment; CCA: Capital Consumption Adjustment

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

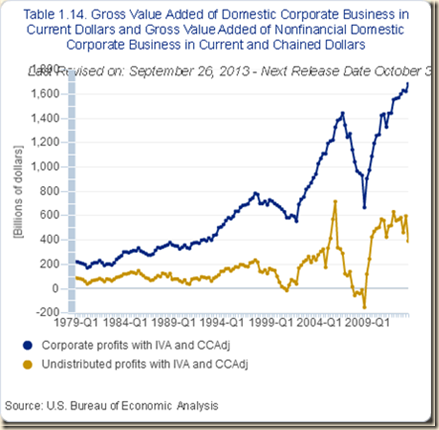

Chart IA1-12 of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis provides quarterly corporate profits after tax and undistributed profits with IVA and CCA from 1979 to 2013. There is tightness between the series of quarterly corporate profits and undistributed profits in the 1980s with significant gap developing from 1988 and to the present with the closest approximation peaking in IVQ2005 and surrounding quarters. These gaps widened during all recessions including in 1991 and 2001 and recovered in expansions with exceptionally weak performance in the current expansion.

Chart IA1-14, US, Corporate Profits after Tax and Undistributed Profits with Inventory Valuation Adjustment and Capital Consumption Adjustment, Quarterly, 1979-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

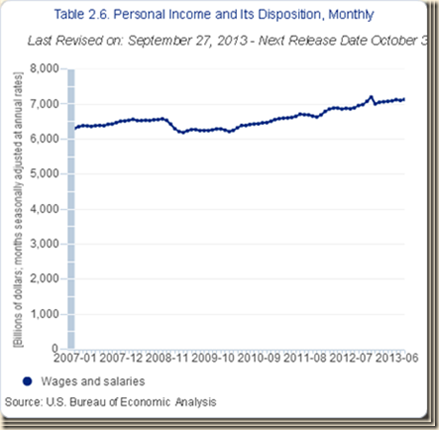

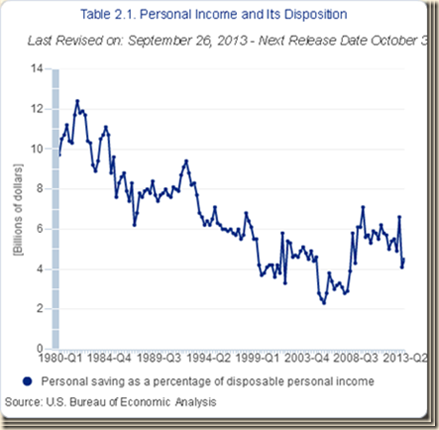

ESVI Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides a wealth of revisions and enhancements of US personal income and outlays since 1929 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0613.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0713.pdf http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0813.pdf http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Table IB-4 provides growth rates of real disposable income and real disposable income per capita in the long-term and selected periods. Real disposable income consists of after-tax income adjusted for inflation. Real disposable income per capita is income per person after taxes and inflation. There is remarkable long-term trend of real disposable income of 3.2 percent per year on average from 1929 to 2012 and 2.0 percent in real disposable income per capita. Real disposable income increased at the average yearly rate of 3.7 percent from 1947 to 1999 and real disposable income per capita at 2.3 percent. These rates of increase broadly accompany rates of growth of GDP. Institutional arrangements in the United States provided the environment for growth of output and income after taxes, inflation and population growth. There is significant break of growth by much lower 2.4 percent for real disposable income on average from 1999 to 2012 and 1.5 percent in real disposable per capita income. Real disposable income grew at 3.5 percent from 1980 to 1989 and real disposable per capita income at 2.6 percent. In contrast, real disposable income grew at only 1.4 percent on average from 2006 to 2012 and real disposable income at 0.6 percent. The United States has interrupted its long-term and cyclical dynamism of output, income and employment growth. Recovery of this dynamism could prove to be a major challenge.