Delays in Updating United States Economic Data, United States Industrial Production, Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation in the Lost Economic Cycle of the Global Recession with Economic Growth Underperforming Below Trend Worldwide World Cyclical Slow Growth, Government Intervention in Globalization, and Global Recession Risk

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019

I United States Industrial Production

IIB Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates

II 1B Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation in the Lost Economic Cycle of the Global Recession with Economic Growth Underperforming Below Trend Worldwide

III World Financial Turbulence

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

I United States Industrial Production. There is socio-economic stress in the combination of adverse events and cyclical performance:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources with GDP two trillion dollars below trend (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/monetary-policy-rates-near-normal.html). US GDP grew at the average rate of 3.2 percent per year from 1929 to 2017, with similar performance in whole cycles of contractions and expansions, but only at 1.5 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2017. GDP in IIIQ2018 is 13.8 percent lower than what it would have been had it grown at trend of 3.0 percent

- Private fixed investment stagnating initially followed by cumulative increase of 26.7 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2018 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/monetary-policy-rates-near-normal.html).

- Twenty-one million or 12.4 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-fed-will-be-patient-adjusting.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/fluctuation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/fluctuations-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/fomc-policy-rate-unchanged-competitive.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/01/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/unchanged-fomc-policy-rate-gradual.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/data-dependent-monetary-policy-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/increasing-interest-rates-twenty-four.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-with-exchange-rate.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/turbulence-of-financial-asset.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/fluctuation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/fluctuations-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/fomc-increases-policy-interest-rate.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/revision-of-united-states-national.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/revision-of-united-states-national.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/fomc-policy-rate-unchanged-competitive.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/stronger-dollar-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/dollar-devaluation-cyclically.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/unchanged-fomc-policy-rate-gradual.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/data-dependent-monetary-policy-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2019/01/recovery-without-hiring-labor.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/slowing-world-economic-growth-and.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/oscillation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/oscillation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/recovery-without-hiring-in-lost.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/dollar-revaluation-recovery-without.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/rising-yields-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/decreasing-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/collateral-effects-of-unwinding.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/01/dollar-devaluation-and-rising.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/fomc-increases-interest-rates-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/increasing-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_40.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-valuation-of.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/flattening-us-treasury-yield-curve.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_14.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-values-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/dollar-revaluation-and-valuations-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rate-uncertainty-and-valuation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/contraction-of-united-states-corporate.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/subdued-foreign-growth-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-volatile_17.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-policy-conundrum-recovery.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/impact-of-monetary-policy-on-exchange.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/dollar-revaluation-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-exchange-rate-struggle-recovery.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/g20-monetary-policy-recovery-without.html)

- Productivity growth fell from 2.1 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2017 and average 2.3 percent per year from 1947 to 2007 to 1.3 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2017, deteriorating future growth and prosperity (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/increase-of-interest-rates-by-monetary.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/weaker-world-economic-growth-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/recovery-without-hiring-in-lost.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/revision-of-united-states-national.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/fomc-increases-interest-rates-with.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/united-states-inflation-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/collateral-effects-of-unwinding.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/fomc-increases-interest-rates-with.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/ii-rules-discretionary-authorities-and.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_40.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/flattening-us-treasury-yield-curve.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_14.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/increasing-interest-rates-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-values-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/quite-high-equity-valuations-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/financial-risks-twenty-six-million.html)

- Output of manufacturing in Dec 2018 at 31.2 percent below long-term trend since 1919 and at 22.5 percent below trend since 1986 (Section II and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/increase-of-interest-rates-by-monetary.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/weaker-world-economic-growth-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/oscillation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/world-inflation-waves-lost-economic.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/continuing-gradual-increases-in-fed.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/dollar-revaluation-united-states_24.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/rising-yields-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/united-states-inflation-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/01/dollar-devaluation-and-increasing.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states_23.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/the-lost-economic-cycle-of-global_25.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/world-inflation-waves-long-term-and.html and earlier) (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/monetary-policy-of-reducing-central.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html

and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/global-contraction-of-valuations-of.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/mediocre-cyclical-economic-growth-with.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2019/01/world-inflation-waves-world-financial_24.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/increase-of-interest-rates-by-monetary.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/weakening-gdp-growth-in-major-economies.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/oscillation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/world-inflation-waves-lost-economic.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/continuing-gradual-increases-in-fed.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/dollar-strengthening-world-inflation.htm and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/rising-yields-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/decreasing-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/01/dollar-devaluation-and-increasing.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/fomc-increases-interest-rates-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/dollar-devaluation-and-decline-of.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/world-inflation-waves-long-term-and.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-valuation-of.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/interest-rate-policy-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/competitive-currency-conflicts-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins of production across countries in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (Section II and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/increase-of-interest-rates-by-monetary.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/weaker-world-economic-growth-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/oscillation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/world-inflation-waves-lost-economic.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/continuing-gradual-increases-in-fed.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/dollar-revaluation-united-states_24.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/rising-yields-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/decreasing-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/united-states-inflation-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/01/dollar-devaluation-and-increasing.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states_23.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/the-lost-economic-cycle-of-global_25.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/world-inflation-waves-long-term-and.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/monetary-policy-of-reducing-central.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-valuation-of.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier) (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/fluctuation-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/11/fluctuations-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/fomc-increases-policy-interest-rate.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/revision-of-united-states-national.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/08/revision-of-united-states-national.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/07/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/stronger-dollar-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/05/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/04/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/02/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/dollar-devaluation-cyclically.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/11/unchanged-fomc-policy-rate-gradual.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/09/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/08/data-dependent-monetary-policy-with.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/growth-uncertainties-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html)

- 43 million in poverty and 29 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1999 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-imf.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by 32.6 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2018 when it would have grown over 40.3 percent at trend of 3.2 percent per year in real terms from IVQ1945 to IIIQ2018 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2019/01/recovery-without-hiring-labor.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/fomc-increases-policy-interest-rate.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/06/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/03/mediocre-cyclical-united-states_31.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/12/dollar-devaluation-cyclically.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/10/destruction-of-household-nonfinancial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/united-states-commercial-banks-united.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/of-course-considerable-uncertainty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-fluctuations-of_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/financial-indecision-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/global-financial-risks-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html). Financial assets increased $34.9 trillion while nonfinancial assets increased $7.1 trillion with likely concentration of wealth in those with access to sophisticated financial investments. Real estate assets adjusted for inflation increased 4.0 percent.

Industrial production increased 0.3 percent in Dec 2018 and increased 0.4 percent in Nov 2018 after increasing 0.1 percent in Oct 2018, with all data seasonally adjusted, as shown in Table I-1. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System conducted the annual revision of industrial production released on Mar 23, 2018 (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm):

“The Federal Reserve has revised its index of industrial production (IP) and the related measures of capacity and capacity utilization.[1] On net, the revisions to total IP for recent years were negative: For the 2015–17 period, the current estimates show rates of change that are 0.4 to 0.7 percentage point lower in each year.[2] Total IP is still reported to have moved up about 22 1/2 percent from the end of the recession in mid-2009 through late 2014. Subsequently, the index declined in 2015, edged down in 2016, and increased in 2017. The incorporation of detailed data for manufacturing from the U.S. Census Bureau's 2016 Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) accounts for the majority of the differences between the current and the previously published estimates.

Revisions to capacity for total industry were mixed. Capacity growth was revised up about 1/2 percentage point for 2016, but revisions to other recent years were negative. Capacity for total industry is estimated to have expanded less than 1 percent in 2015, 2016, and 2017, but it is expected to increase about 2 percent in 2018.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, capacity utilization for total industry stood at 77.0 percent, about 1/2 percentage point below its previous estimate and about 3 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2017) average. The utilization rate for 2016 is also lower than the previous estimate.”

The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production increased 0.3 percent in December after rising 0.4 percent in November. For the fourth quarter as a whole, total industrial production moved up at an annual rate of 3.8 percent. In December, manufacturing output increased 1.1 percent, its largest gain since February 2018. The output of mines rose 1.5 percent, but the index for utilities fell 6.3 percent, as warmer-than-usual temperatures lowered the demand for heating. At 109.9 percent of its 2012 average, total industrial production was 4.0 percent higher in December than it was a year earlier. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector rose 0.1 percentage point in December to 78.7 percent, a rate that is 1.1 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2017) average.” In the six months ending in Dec 2018, United States national industrial production accumulated change of 2.2 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 4.5 percent, which is higher than growth of 4.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2018. Excluding growth of 0.8 percent in Aug 2018, growth in the remaining five months from Jul to Dec 2018 accumulated to 1.4 percent or 3.4 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production increased 0.8 percent in one of the past six months, increased 0.4 percent in two months, 0.3 percent in one month, 0.2 percent in one month and 0.1 percent in one month. Industrial production increased at annual equivalent 3.7 percent in the most recent quarter from Oct 2018 to Dec 2018 and increased at 5.3 percent in the prior quarter Jul 2018 to Sep 2018. Business equipment accumulated change of 4.0 percent in the six months from Jul 2018 to Dec 2018, at the annual equivalent rate of 8.1 percent, which is higher than growth of 5.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2018. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “Capacity utilization for the industrial sector rose 0.1 percentage point in December to 78.7 percent, a rate that is 1.1 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2017) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate followed by possible acceleration and weakening growth in past months. There could be renewed growth.

Table I-1, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization, SA, ∆%

| Dec 18 | Nov 18 | Oct 18 | Sep 18 | Aug 18 | Jul 18 | Dec 18/ Dec 17 | |

| Total | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 4.0 |

| Market | |||||||

| Final Products | 0.2 | -0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.6 |

| Consumer Goods | 0.0 | -0.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Business Equipment | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

| Non | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | -0.3 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.7 |

| Construction | 1.6 | 0.2 | -0.4 | -0.7 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 2.1 |

| Materials | 0.5 | 1.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 6.1 |

| Industry Groups | |||||||

| Manufacturing | 1.1 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 3.2 |

| Mining | 1.5 | 1.1 | -0.2 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 13.4 |

| Utilities | -6.3 | 1.3 | 3.3 | -1.3 | 1.1 | 0.2 | -4.3 |

| Capacity | 78.7 | 78.6 | 78.4 | 78.4 | 78.5 | 78.0 | 2.1 |

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Manufacturing increased 1.1 percent in Dec 2018 and increased 0.1 percent in Nov 2018 after decreasing 0.2 percent in Oct 2018, seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.0 percent not seasonally adjusted in the 12 months ending in Dec 2018, as shown in Table I-2. Manufacturing increased cumulatively 2.1 percent in the six months ending in Dec 2018 or at the annual equivalent rate of 4.3 percent. Excluding the increase of 1.1 percent in Dec 2018, manufacturing changed 1.0 percent from Jul 2018 to Dec 2018 or at the annual equivalent rate of 2.4 percent. Table I-2 provides a longer perspective of manufacturing in the US. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 with recovery followed by renewed deterioration/improvement in more recent months as shown by 12 months’ rates of growth. Growth rates appeared to be increasing again closer to 5 percent in Apr-Jun 2012 but deteriorated. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appeared to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession, but the pace of manufacturing fell steadily with some strength at the margin. There is renewed deterioration and improvement. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System conducted the annual revision of industrial production released on Mar 23, 2018 (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm):

“The Federal Reserve has revised its index of industrial production (IP) and the related measures of capacity and capacity utilization.[1] On net, the revisions to total IP for recent years were negative: For the 2015–17 period, the current estimates show rates of change that are 0.4 to 0.7 percentage point lower in each year.[2] Total IP is still reported to have moved up about 22 1/2 percent from the end of the recession in mid-2009 through late 2014. Subsequently, the index declined in 2015, edged down in 2016, and increased in 2017. The incorporation of detailed data for manufacturing from the U.S. Census Bureau's 2016 Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) accounts for the majority of the differences between the current and the previously published estimates.

Revisions to capacity for total industry were mixed. Capacity growth was revised up about 1/2 percentage point for 2016, but revisions to other recent years were negative. Capacity for total industry is estimated to have expanded less than 1 percent in 2015, 2016, and 2017, but it is expected to increase about 2 percent in 2018.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, capacity utilization for total industry stood at 77.0 percent, about 1/2 percentage point below its previous estimate and about 3 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2017) average. The utilization rate for 2016 is also lower than the previous estimate.”

The bottom part of Table I-2 shows manufacturing decreasing 22.3 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increasing 16.1 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2017. Manufacturing grew 19.6 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2018. Manufacturing in Dec 2018 is lower by 7.1 percent relative to the peak in Jun 2007. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.3 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 37 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIIQ2018. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the third estimate of GDP for IIIQ2018 (https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2018-12/gdp3q18_3rd_1.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.8 percent obtained by dividing GDP of $15,557.3 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $15,134.1 billion in IIQ2009 {[($15,557.3/$15,134.1) -1]100 = 2.8%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/monetary-policy-rates-near-normal.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent, 5.3 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.1 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1989, 4.6 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1989, 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1989. 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1990, 4.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1990, 4.3 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1990, 4.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1990, 3.8 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1991, 3.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1991, 3.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1991, 3.7 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1991, 3.7 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1992 and at 7.9 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/monetary-policy-rates-near-normal.html). The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates a contraction of the US from IQ1990 (Jul) to IQ1991 (Mar) (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). The expansion lasted until another contraction beginning in IQ2001 (Mar). US GDP contracted 1.3 percent from the pre-recession peak of $8983.9 billion of chained 2009 dollars in IIIQ1990 to the trough of $8865.6 billion in IQ1991 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2018 would have accumulated to 37.4 percent. GDP in IIIQ2018 would be $21,657.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2012) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2992.0 billion than actual $18,665.0 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 21.2 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment/underemployment of 12.4 percent of the effective labor force (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2019/01/the-fed-will-be-patient-adjusting.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/fluctuation-of-valuations-of-risk.html). US GDP in IIIQ2018 is 13.8 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $15,762.0 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $18,665.0 billion in IIIQ2018 or 18.4 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.6 percent. Professor John H. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. Cochrane (2016May02) measures GDP growth in the US at average 3.5 percent per year from 1950 to 2000 and only at 1.76 percent per year from 2000 to 2015 with only at 2.0 percent annual equivalent in the current expansion. Cochrane (2016May02) proposes drastic changes in regulation and legal obstacles to private economic activity. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Dec 1919 to Dec 2018. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.3221 in Dec 2007 to 151.5426 in Dec 2018. The actual index NSA in Dec 2018 is 104.3366, which is 31.2 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.0 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2018. Using trend growth of 2.0 percent per year, the index would increase to 134.6444 in Dec 2018. The output of manufacturing at 104.3366 in Dec 2018 is 22.5 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table I-2, US, Monthly and 12-Month Rates of Growth of Manufacturing ∆%

| Month SA ∆% | 12-Month NSA ∆% | |

| Dec 2018 | 1.1 | 3.0 |

| Nov | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Oct | -0.2 | 2.2 |

| Sep | 0.2 | 3.9 |

| Aug | 0.5 | 3.5 |

| Jul | 0.4 | 2.7 |

| Jun | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| May | -1.0 | 1.4 |

| Apr | 0.6 | 3.3 |

| Mar | -0.1 | 2.4 |

| Feb | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Jan | -0.5 | 0.9 |

| Dec 2017 | 0.0 | 1.8 |

| Nov | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| Oct | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Sep | -0.1 | 0.7 |

| Aug | -0.2 | 1.2 |

| Jul | -0.3 | 1.4 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| May | -0.4 | 1.8 |

| Apr | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Mar | -0.5 | 1.1 |

| Feb | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Jan | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Dec 2016 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Nov | 0.0 | -0.2 |

| Oct | 0.2 | -0.3 |

| Sep | 0.3 | -0.2 |

| Aug | -0.3 | -1.5 |

| Jul | 0.2 | -1.4 |

| Jun | 0.3 | -0.8 |

| May | -0.1 | -1.5 |

| Apr | -0.3 | -0.8 |

| Mar | -0.2 | -1.8 |

| Feb | -0.4 | -0.6 |

| Jan | 0.5 | -0.7 |

| Dec 2015 | -0.2 | -1.9 |

| Nov | -0.2 | -1.7 |

| Oct | 0.0 | -0.8 |

| Sep | -0.4 | -1.7 |

| Aug | -0.3 | -0.7 |

| Jul | 0.6 | -0.4 |

| Jun | -0.4 | -1.1 |

| May | -0.1 | -0.3 |

| Apr | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Mar | 0.3 | -0.1 |

| Feb | -0.6 | 0.5 |

| Jan | -0.5 | 1.9 |

| Dec 2014 | -0.3 | 1.5 |

| Nov | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| Oct | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Sep | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Aug | -0.4 | 1.3 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| May | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Apr | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Mar | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Feb | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| Jan | -1.2 | -0.5 |

| Dec 2013 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Nov | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Oct | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| Sep | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Aug | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Jul | -1.0 | 0.3 |

| Jun | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| May | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Apr | -0.4 | 1.0 |

| Mar | -0.1 | 0.6 |

| Feb | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Jan | -0.3 | 0.8 |

| Dec 2012 | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| Nov | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| Oct | -0.4 | 0.7 |

| Sep | -0.1 | 1.6 |

| Aug | -0.2 | 2.1 |

| Jul | -0.1 | 2.5 |

| Jun | 0.2 | 3.4 |

| May | -0.4 | 3.4 |

| Apr | 0.6 | 3.8 |

| Mar | -0.5 | 2.8 |

| Feb | 0.4 | 4.1 |

| Jan | 0.8 | 3.5 |

| Dec 2011 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Nov | -0.3 | 2.7 |

| Oct | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| Sep | 0.3 | 2.6 |

| Aug | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Jul | 0.6 | 2.3 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| May | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| Apr | -0.6 | 2.7 |

| Mar | 0.6 | 4.2 |

| Feb | 0.1 | 4.8 |

| Jan | 0.2 | 4.8 |

| Dec 2010 | 0.5 | 5.4 |

| Nov | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| Oct | 0.1 | 5.8 |

| Sep | 0.0 | 6.1 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 6.8 |

| Jul | 0.6 | 7.4 |

| Jun | -0.1 | 9.2 |

| May | 1.4 | 8.9 |

| Apr | 0.8 | 7.3 |

| Mar | 1.2 | 5.2 |

| Feb | -0.1 | 1.7 |

| Jan | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Dec 2009 | -0.2 | -2.9 |

| Nov | 1.0 | -5.8 |

| Oct | 0.2 | -8.9 |

| Sep | 0.9 | -10.4 |

| Aug | 1.1 | -13.5 |

| Jul | 1.5 | -15.3 |

| Jun | -0.3 | -17.9 |

| May | -1.0 | -17.9 |

| Apr | -0.7 | -18.6 |

| Mar | -1.8 | -17.8 |

| Feb | -0.2 | -16.7 |

| Jan | -3.1 | -17.0 |

| Dec 2008 | -3.5 | -14.5 |

| Nov | -2.4 | -11.7 |

| Oct | -0.6 | -9.2 |

| Sep | -3.4 | -8.8 |

| Aug | -1.2 | -5.2 |

| Jul | -1.2 | -3.7 |

| Jun | -0.7 | -3.2 |

| May | -0.6 | -2.4 |

| Apr | -1.1 | -1.0 |

| Mar | -0.3 | -0.5 |

| Feb | -0.6 | 1.1 |

| Jan | -0.4 | 2.5 |

| Dec 2007 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| Nov | 0.5 | 3.5 |

| Oct | -0.3 | 2.9 |

| Sep | 0.5 | 3.0 |

| Aug | -0.3 | 2.7 |

| Jul | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 3.1 |

| May | -0.1 | 3.2 |

| Apr | 0.7 | 3.6 |

| Mar | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| Feb | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| Jan | -0.5 | 1.2 |

| Dec 2006 | 2.7 | |

| Dec 2005 | 3.6 | |

| Dec 2004 | 4.1 | |

| Dec 2003 | 2.2 | |

| Dec 2002 | 2.4 | |

| Dec 2001 | -5.3 | |

| Dec 2000 | 0.8 | |

| Dec 1999 | 5.2 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2018 | 2.0 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2017 | 2.0 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2016 | 2.0 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2015 | 2.0 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2014 | 2.2 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2013 | 2.2 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 1999 | 4.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1999-Dec 2006 | 1.5 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1999-Dec 2017 | 0.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1999-Dec 2018 | 0.4 | |

| ∆% Peak 112.3300 in 06/2007 to 101.3446 in 12/2017 | -9.8 | |

| ∆% Peak 112.3300 in 06/2007 to Trough 87.2739 in 4/2009 | -22.3 | |

| ∆% Trough 87.2739 in 04/2009 to 101.3446 in 12/2017 | 16.1 | |

| ∆% Trough 87.2739 in 04/2009 to 104.3366 in 12/2018 | 19.6 | |

| ∆% Peak 112.3300 in 06/2007 to 104.3366 in 12/2018 | -7.1 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

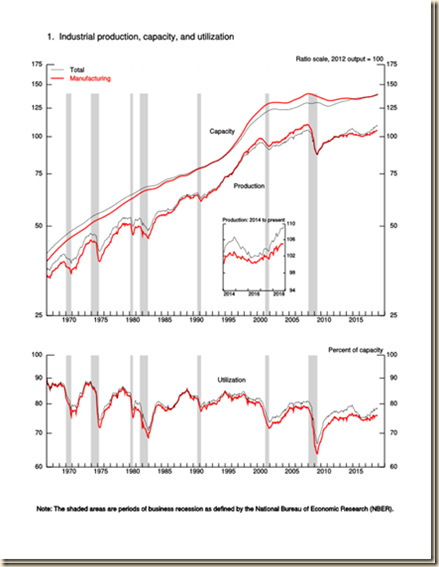

Chart I-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides industrial production, manufacturing and capacity since the 1970s. There was acceleration of growth of industrial production, manufacturing and capacity in the 1990s because of rapid growth of productivity in the US (Cobet and Wilson (2002); see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 135-44). The slopes of the curves flatten in the 2000s. Production and capacity have not recovered sufficiently above levels before the global recession, remaining like GDP below historical trend. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Dec 1919 to Dec 2018. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.3221 in Dec 2007 to 151.5426 in Dec 2018. The actual index NSA in Dec 2018 is 104.3366, which is 31.2 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.0 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2018. Using trend growth of 2.0 percent per year, the index would increase to 134.6444 in Dec 2018. The output of manufacturing at 104.3366 in Dec 2018 is 22.5 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Chart I-1, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg1.gif

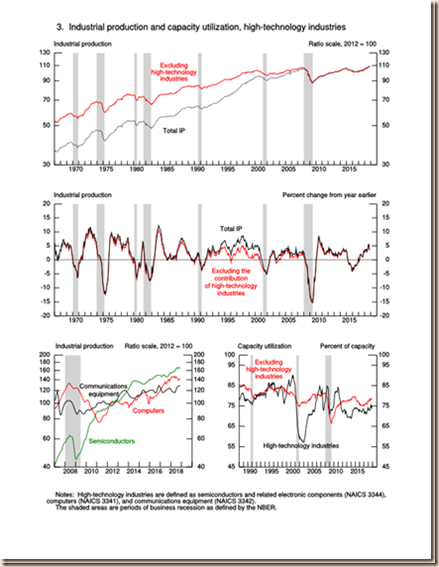

The modern industrial revolution of Jensen (1993) is captured in Chart I-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (for the literature on M&A and corporate control see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009a), 143-56, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), 49-59, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 46-49). The slope of the curve of total industrial production accelerates in the 1990s to a much higher rate of growth than the curve excluding high-technology industries. Growth rates decelerate into the 2000s and output and capacity utilization have not recovered fully from the strong impact of the global recession. Growth in the current cyclical expansion has been more subdued than in the prior comparably deep contractions in the 1970s and 1980s. Chart I-2 shows that the past recessions after World War II are the relevant ones for comparison with the recession after 2007 instead of common comparisons with the Great Depression (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/12/monetary-policy-rates-near-normal.html). The bottom left-hand part of Chart II-2 shows the strong growth of output of communication equipment, computers and semiconductor that continued from the 1990s into the 2000s. Output of semiconductors has already surpassed the level before the global recession.

Chart I-2, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization of High Technology Industries

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg3.gif

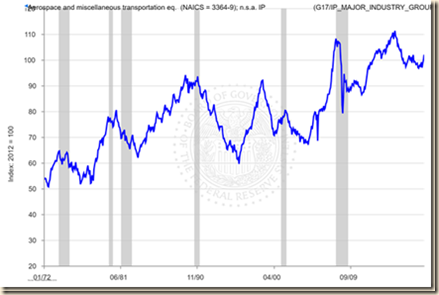

Additional detail on industrial production and capacity utilization is in Chart I-3 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Production of consumer durable goods fell sharply during the global recession by more than 30 percent and is oscillating above the level before the contraction. Output of nondurable consumer goods fell around 10 percent and is some 5 percent below the level before the contraction. Output of business equipment fell sharply during the contraction of 2001 but began rapid growth again after 2004. An important characteristic is rapid growth of output of business equipment in the cyclical expansion after sharp contraction in the global recession, stalling in the final segment. Output of defense and space only suffered reduction in the rate of growth during the global recession and surged ahead of the level before the contraction, declining in the final segment. Output of construction supplies collapsed during the global recession and is well below the level before the contraction. Output of energy materials was stagnant before the contraction but recovered sharply above the level before the contraction with alternating recent decline/improvement.

Chart I-3, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg2.gif

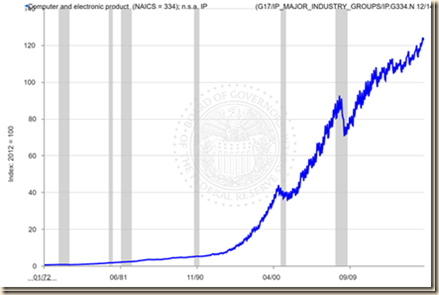

United States manufacturing output from 1919 to 2018 monthly is in Chart I-4 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The second industrial revolution of Jensen (1993) is quite evident in the acceleration of the rate of growth of output given by the sharper slope in the 1980s and 1990s. Growth was robust after the shallow recession of 2001 but dropped sharply during the global recession after IVQ2007. Manufacturing output recovered sharply but has not reached earlier levels and is losing momentum at the margin. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Dec 1919 to Dec 2018. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.3221 in Dec 2007 to 151.5426 in Dec 2018. The actual index NSA in Dec 2018 is 104.3366, which is 31.2 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.0 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2018. Using trend growth of 2.0 percent per year, the index would increase to 134.6444 in Dec 2018. The output of manufacturing at 104.3366 in Dec 2018 is 22.5 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Chart I-4, US, Manufacturing Output, 1919-2018

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Manufacturing jobs not seasonally adjusted increased 284,000 from Dec 2017 to

Dec 2018 or at the average monthly rate of 23,667. Industrial production increased 0.3 percent in Dec 2018 and increased 0.4 percent in Nov 2018 after increasing 0.2 percent in Oct 2018, with all data seasonally adjusted. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System conducted the annual revision of industrial production released on Mar 23, 2018 (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm):

“The Federal Reserve has revised its index of industrial production (IP) and the related measures of capacity and capacity utilization.[1] On net, the revisions to total IP for recent years were negative: For the 2015–17 period, the current estimates show rates of change that are 0.4 to 0.7 percentage point lower in each year.[2] Total IP is still reported to have moved up about 22 1/2 percent from the end of the recession in mid-2009 through late 2014. Subsequently, the index declined in 2015, edged down in 2016, and increased in 2017. The incorporation of detailed data for manufacturing from the U.S. Census Bureau's 2016 Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) accounts for the majority of the differences between the current and the previously published estimates.

Revisions to capacity for total industry were mixed. Capacity growth was revised up about 1/2 percentage point for 2016, but revisions to other recent years were negative. Capacity for total industry is estimated to have expanded less than 1 percent in 2015, 2016, and 2017, but it is expected to increase about 2 percent in 2018.

In the fourth quarter of 2017, capacity utilization for total industry stood at 77.0 percent, about 1/2 percentage point below its previous estimate and about 3 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2017) average. The utilization rate for 2016 is also lower than the previous estimate.”