Global Contraction of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets, Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits and Fiscal Imbalance Threatening Risk Premium on Treasury Securities, United States Inflation, United States International Trade, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation in the Lost Economic Cycle of the Global Recession with Economic Growth Underperforming Below Trend Worldwide, World Financial Turbulence, World Cyclical Slow Growth, Government Intervention in Globalization, and Global Recession Risk

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018

IA Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits and Fiscal Imbalance Threatening Risk Premium on Treasury Securities

IC United States Inflation

IC Long-term US Inflation

ID Current US Inflation

IIA United States International Trade

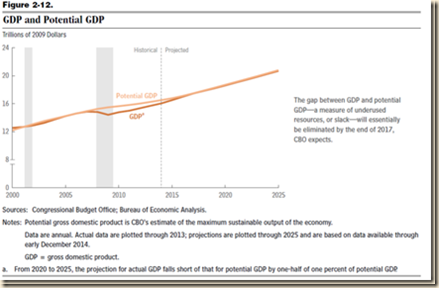

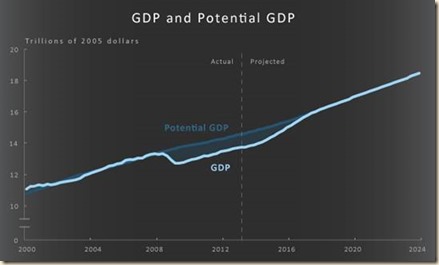

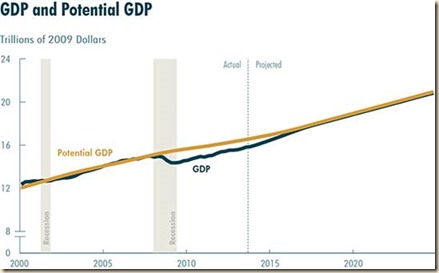

II IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation in the Lost Economic Cycle of the Global Recession with Economic Growth Underperforming Below Trend Worldwide

III World Financial Turbulence

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IA Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits and Fiscal Imbalance Threatening Risk Premium on Treasury Securities. Table IIA1-1 of the CBO (https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6) shows the significant worsening of United States fiscal affairs from 2007-2008 to 2009-2012 with marginal improvement in 2013-2015 but with much higher debt relative to GDP. The deficit of $1.1 trillion in fiscal year 2012 was the fourth consecutive federal deficit exceeding one trillion dollars. All four deficits are the highest in share of GDP since 1946 (https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6). There is new deterioration in 2016 with increase of the debt/GDP to 3.2 percent and further deterioration in 2017 with debt/GDP increasing to 3.5 percent.

Table IAI-1, US, Budget Fiscal Year Totals, Billions of Dollars and % GDP

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Receipts | 2568 | 2524 | 2105 | 2163 | 2303 |

| Outlays | 2729 | 2983 | 3518 | 3457 | 3603 |

| Deficit | -161 | -459 | 1413 | 1294 | 1300 |

| % GDP | -1.1 | -3.1 | -9.8 | -8.7 | -8.5 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Receipts | 2450 | 2775 | 3021 | 3250 | 3268 |

| Outlays | 3537 | 3455 | 3506 | 3688 | 3853 |

| Deficit | 1087 | 680 | -485 | -438 | -585 |

| % GDP | -6.8 | -4.1 | -2.8 | -2.4 | -3.2 |

| 2017 | |||||

| Receipts | 3316 | ||||

| Outlays | 3982 | ||||

| Deficit | -665 | ||||

| % GDP | -3.5 |

Source: https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#2 The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2017-2027. Washington, DC, Jan 24, 2017 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52370

CBO, An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Aug 23, 2016.

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6 CBO (2012NovMBR), CBO (2013BEOFeb5), CBO (2013HBDFeb5), CBO (2013Aug12). CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, Historical Budget Data—April 2014, Washington DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14. CBO, Historical budget data—August 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Aug 27. CBO, Monthly budget review: summary of fiscal year 2014. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Nov 10, 2014. CBO, Historical Budget Data, January 2015 Baseline from Budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Jan 26. CBO. 2015. An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 25.

Table IIA1-2 provides additional information required for understanding the deficit/debt situation of the United States. The table is divided into four parts: Treasury budget in the 2018 fiscal year beginning on Oct 1, 2017 and ending on Sep 30, 2018; federal fiscal data for the years from 2009 to 2017; federal fiscal data for the years from 2005 to 2008; and Treasury debt held by the public from 2005 to 2017. Receipts increased 0.6 percent in the cumulative fiscal year 2018 ending in Aug 2018 relative to the cumulative in fiscal year 2017. Individual income taxes increased 7.0 percent relative to the same fiscal period a year earlier. Outlays increased 6.7 percent relative to a year earlier. There are also receipts, outlays, deficit and debt for fiscal years 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017. In fiscal year 2017, the deficit reached $666 billion or 3.5 percent of GDP. Outlays of 3,982 billion were 20.8 percent of GDP and receipts of $3,316 were 17.3 percent of GDP. It is quite difficult for the US to raise receipts above 18 percent of GDP. Total revenues of the US from 2009 to 2012 accumulate to $9022 billion, or $9.0 trillion, while expenditures or outlays accumulate to $14,115 billion, or $14.1 trillion, with the deficit accumulating to $5094 billion, or $5.1 trillion. Revenues decreased 6.5 percent from $9653 billion in the four years from 2005 to 2008 to $9022 billion in the years from 2009 to 2012. Decreasing revenues were caused by the global recession from IVQ2007 (Dec) to IIQ2009 (Jun) and by growth of only 2.3 percent on average in the cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2018. In contrast, the expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1991 was at the average annual growth rate of 3.7 percent and at 7.9 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/fomc-increases-policy-interest-rate.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/revision-of-united-states-national.html). Because of mediocre GDP growth, there are 20.7 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment/underemployment rate of 12.1 percent (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/10/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/twenty-one-million-unemployed-or.html). Weakness of growth and employment creation is analyzed in II Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation (Section II and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html). In contrast with the decline of revenue, outlays or expenditures increased 30.2 percent from $10,839 billion, or $10.8 trillion, in the four years from 2005 to 2008, to $14,115 billion, or $14.1 trillion, in the four years from 2009 to 2012. Increase in expenditures by 30.2 percent while revenue declined by 6.5 percent caused the increase in the federal deficit from $1186 billion in 2005-2008 to $5094 billion in 2009-2012. Federal revenue was 14.9 percent of GDP on average in the years from 2009 to 2012, which is well below 17.4 percent of GDP on average from 1968 to 2017. Federal outlays were 23.3 percent of GDP on average from 2009 to 2012, which is well above 20.3 percent of GDP on average from 1968 to 2017. The lower part of Table IIA1-2 shows that debt held by the public swelled from $5803 billion in 2008 to $13,117 billion in 2015, by $7314 billion or 126.0 percent. Debt held by the public as percent of GDP or economic activity jumped from 39.3 percent in 2008 to 76.5 percent in 2017, which is well above the average of 40.7 percent from 1968 to 2017. The United States faces tough adjustment because growth is unlikely to recover, creating limits on what can be obtained by increasing revenues, while continuing stress of social programs restricts what can be obtained by reducing expenditures.

Table IIA1-2, US, Treasury Budget in Fiscal Year to Date Million Dollars

| Aug | Fiscal Year 2018 | Fiscal Year 2017 | ∆% |

| Receipts | 2,985,186 | 2,966,172 | 0.6 |

| Outlays | 3,883,298 | 3,639,883 | 6.7 |

| Deficit | -683,965 | -566,023 | |

| Individual Income Tax | 1,521,589 | 1,421,997 | 7.0 |

| Corporation Income Tax | 162,551 | 233,631 | -30.4 |

| Social Insurance | 779,944 | 778,644 | 0.2 |

| Receipts | Outlays | Deficit (-), Surplus (+) | |

| $ Billions | |||

| Fiscal Year 2017 | 3,316 | 3,982 | -666 |

| % GDP | 17.3 | 20.8 | -3.5 |

| Fiscal Year 2016 | 3,268 | 3,853 | -585 |

| % GDP | 17.7 | 20.9 | -3.2 |

| Fiscal Year 2015 | 3,250 | 3,688 | -439 |

| % GDP | 18.1 | 20.5 | -2.4 |

| Fiscal Year 2014 | 3,022 | 3,506 | -485 |

| % GDP | 17.5 | 20.3 | 2.8 |

| Fiscal Year 2013 | 2,775 | 3,455 | -680 |

| % GDP | 16.8 | 20.9 | -4.1 |

| Fiscal Year 2012 | 2,450 | 3,537 | -1,087 |

| % GDP | 15.3 | 22.1 | -6.8 |

| Fiscal Year 2011 | 2,304 | 3,603 | -1,300 |

| % GDP | 15.0 | 23.4 | -8.5 |

| Fiscal Year 2010 | 2,163 | 3,457 | -1,294 |

| % GDP | 14.6 | 23.4 | -8.7 |

| Fiscal Year 2009 | 2,105 | 3,518 | -1,413 |

| % GDP | 14.6 | 24.4 | -9.8 |

| Total 2009-2012 | 9,022 | 14,115 | -5,094 |

| Average % GDP 2009-2012 | 14.9 | 23.3 | -8.5 |

| Fiscal Year 2008 | 2,524 | 2,983 | -459 |

| % GDP | 17.1 | 20.2 | -3.1 |

| Fiscal Year 2007 | 2,568 | 2,729 | -161 |

| % GDP | 17.9 | 19.1 | -1.1 |

| Fiscal Year 2006 | 2,407 | 2,655 | -248 |

| % GDP | 17.6 | 19.4 | -1.8 |

| Fiscal Year 2005 | 2,154 | 2,472 | -318 |

| % GDP | 16.7 | 19.2 | -2.5 |

| Total 2005-2008 | 9,653 | 10,839 | -1,186 |

| Average % GDP 2005-2008 | 17.3 | 19.5 | -2.1 |

| Debt Held by the Public | Billions of Dollars | Percent of GDP | |

| 2005 | 4,592 | 35.6 | |

| 2006 | 4,829 | 35.3 | |

| 2007 | 5,035 | 35.2 | |

| 2008 | 5,803 | 39.3 | |

| 2009 | 7,545 | 52.3 | |

| 2010 | 9,019 | 60.9 | |

| 2011 | 10,128 | 65.9 | |

| 2012 | 11,281 | 70.4 | |

| 2013 | 11,983 | 72.6 | |

| 2014 | 12,780 | 74.1 | |

| 2015 | 13,117 | 72.9 | |

| 2016 | 14,168 | 76.7 | |

| 2017 | 14,666 | 76.5 |

Source: http://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/fsreports/rpt/mthTreasStmt/mthTreasStmt_home.htm

https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0184.aspx CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2017-2027. Washington, DC, Jan 24, 2017 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52370 CBO, An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Aug 23, 2016.

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6

CBO (2012NovMBR). CBO (2011AugBEO); Office of Management and Budget 2011. Historical Tables. Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2011. Washington, DC: OMB; CBO. 2011JanBEO. Budget and Economic Outlook. Washington, DC, Jan. CBO. 2012AugBEO. Budget and Economic Outlook. Washington, DC, Aug 22. CBO. 2012Jan31. Historical budget data. Washington, DC, Jan 31. CBO. 2012NovCDR. Choices for deficit reduction. Washington, DC. Nov. CBO. 2013HBDFeb5. Historical budget data—February 2013 baseline projections. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 5. CBO. 2013HBDFeb5. Historical budget data—February 2013 baseline projections. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 5. CBO (2013Aug12). 2013AugHBD. Historical budget data—August 2013. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Aug. CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, Historical budget data—April 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr. Congressional Budget Office, August 2014 baseline: an update to the budget and economic outlook: 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 27, 2014. CBO, Monthly budget review: summary of fiscal year 2014. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Nov 10, 2014. CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jan 26, 2015.

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#2

Total outlays of the federal government of the United States have grown to extremely high levels. Table IIA1-4 of the CBO (CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6) provides total outlays in 2006 and 2017. Total outlays of $3981.6 billion in 2017, or $4.0 trillion, are higher by $1326.5 billion, or $1.2 trillion, relative to $2655.1 billion in 2006, or $2.7 trillion. Outlays have grown from 19.4 percent of GDP in 2006 to 20.8 percent of GDP in 2017. Outlays as percent of GDP were on average 20.3 percent from 1968 to 2017 and receipts as percent of GDP were on average 17.4 percent of GDP. It has proved extremely difficult to increase receipts above 19 percent of GDP. Mandatory outlays increased from $1411.8 billion in 2006 to $2518.8 billion in 2017, by $1107.0 billion. The first to the final row shows that the total of social security, Medicare, Medicaid, Income Security, net interest and defense absorbs 79.4 percent of US total outlays, which is equal to 16.6 percent of GDP. There has been no meaningful constraint of spending, which is quite difficult because of the rigid structure of social programs.

Table IIA1-4, US, Central Government Total Revenue and Outlays, Billions of Dollars and Percent

| 2006 | % Total | 2017 | % Total | |

| I TOTAL REVENUE $B | 2406.9 | 100.0 | 3316.2 | 100.0 |

| % GDP | 17.6 | 17.3 | ||

| Individual Income Taxes $B | 1043.9 | 1587.1 | ||

| % GDP | 7.6 | 8.3 | ||

| Corporate Income Taxes $B | 353.9 | 297.0 | ||

| % GDP | 2.6 | 1.5 | ||

| Social Insurance Taxes | 837.8 | 1161.9 | ||

| % GDP | 6.1 | 6.1 | ||

| II TOTAL OUTLAYS | 2655.1 | 3981.6 | ||

| % GDP | 19.4 | 20.8 | ||

| Discretionary | 1016.6 | 1200.2 | ||

| % GDP | 7.4 | 6.3 | ||

| Defense | 520.0 | 590.2 | ||

| % GDP | 3.8 | 3.1 | ||

| Nondefense | 496.7 | 610.0 | ||

| % GDP | 3.6 | 3.2 | ||

| Mandatory | 1411.8 | 2518.8 | ||

| % GDP | 10.3 | 13.1 | ||

| Social Security | 543.9 | 939.2 | ||

| % GDP | 4.0 | 4.9 | ||

| Medicare | 376.8 | 702.3 | ||

| % GDP | 2.8 | 3.7 | ||

| Medicaid | 180.6 | 374.7 | ||

| % GDP | 1.3 | 2.0 | ||

| Income Security | 200.0 | 293.3 | ||

| % GDP | 1.5 | 1.5 | ||

| Offsetting Receipts | -144.3 | -253.0 | ||

| % GDP | -1.1 | -1.3 | ||

| Net Interest | 226.6 | 262.6 | ||

| % GDP | 1.7 | 1.4 | ||

| Defense +Medicare | 2047.9 | 77.1* | 3162.3 | 79.4* |

| % GDP | 15.1 | 16.6 |

*Percent of Total Outlays

Source: https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#2

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3 CBO (2013Aug12). CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651 2013AugHBD. Historical budget data—August 2013. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Aug. CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, Historical budget data—April 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr. CBO, Historical budget data—August 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Aug 27. CBO, Historical budget data—August 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Aug 27. CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jan 26, 2015.

The US is facing a major fiscal challenge. Table IIA1-5 provides federal revenues, expenditures, deficit and debt as percent of GDP and the yearly change in GDP in the more than eight decades from 1930 to 2017. The most recent period of debt exceeding 90 percent of GDP based on yearly observations in Table IIA1-5 is between 1944 and 1948. The data in Table IIA-15 use the earlier GDP estimates of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) until 1972 for the ratios to GDP of revenue, expenditures, deficit and debt and the revised CBO (https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6) after 1973 that incorporate the new BEA GDP estimates (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The percentage change of GDP is based on the new BEA estimates for all years since 1929. The debt/GDP ratio rose to 106.2 percent of GDP in 1945 and to 108.7 percent of GDP in 1946. GDP fell revised 11.6 percent in 1946, which is only matched in Table I-5 by the decline of revised 12.9 percent in 1932. Part of the decline is explained by the bloated US economy during World War II, growing at revised 17.7 percent in 1941, 18.9 percent in 1942 and 17.0 percent in 1943. Expenditures as a share of GDP rose to their highest in the series: 43.6 percent in 1943, 43.6 percent in 1944 and 41.9 percent in 1945. The repetition of 43.6 percent in 1943 and 1944 is in the original source of Table IIA1-5. During the Truman administration from Apr 1945 to Jan 1953, the federal debt held by the public fell systematically from the peak of 108.7 percent of GDP in 1946 to 61.6 percent of GDP in 1952. During the Eisenhower administration from Jan 1953 to Jan 1961, the federal debt held by the public fell from 58.6 percent of GDP in 1953 to 45.6 percent of GDP in 1960. The Truman and Eisenhower debt reductions were facilitated by diverse factors such as low interest rates, lower expenditure/GDP ratios that could be attained again after lowering war outlays and less rigid structure of mandatory expenditures than currently. There is no subsequent jump of debt as the one from revised 39.3 percent of GDP in 2008 to 65.9 percent of GDP in 2011, 70.4 percent in 2012, 72.6 percent in 2013 and 74.1 percent in 2014. The debt/GDP ratio eased slightly to 72.9 percent in 2015, increasing to 76.7 percent in 2016. The debt/GDP ratio stabilized at 76.5 percent in 2017.

Table IIA1-5, United States Central Government Revenue, Expenditure, Deficit, Debt and GDP Growth 1930-2016

| Rev | Exp | Deficit | Debt | GDP | |

| 1930 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 0.8 | -8.5 | |

| 1931 | 3.7 | 4.3 | -0.6 | -6.4 | |

| 1932 | 2.8 | 6.9 | -4.0 | -12.9 | |

| 1933 | 3.5 | 8.0 | -4.5 | -1.3 | |

| 1934 | 4.8 | 10.7 | -5.9 | 10.8 | |

| 1935 | 5.2 | 9.2 | -4.0 | 8.9 | |

| 1936 | 5.0 | 10.5 | -5.5 | 12.9 | |

| 1937 | 6.1 | 8.6 | -2.5 | 5.1 | |

| 1938 | 7.6 | 7.7 | -0.1 | -3.3 | |

| 1939 | 7.1 | 10.3 | -3.2 | 8.0 | |

| 1940s | |||||

| 1940 | 6.8 | 9.8 | -3.0 | 44.2 | 8.8 |

| 1941 | 7.6 | 12.0 | -4.3 | 42.3 | 17.7 |

| 1942 | 10.1 | 24.3 | -14.2 | 47.0 | 18.9 |

| 1943 | 13.3 | 43.6 | -30.3 | 70.9 | 17.0 |

| 1944 | 20.9 | 43.6 | -22.7 | 88.3 | 8.0 |

| 1945 | 20.4 | 41.9 | -21.5 | 106.2 | -1.0 |

| 1946 | 17.7 | 24.8 | -7.2 | 108.7 | -11.6 |

| 1947 | 16.5 | 14.8 | 1.7 | 96.2 | -1.1 |

| 1948 | 16.2 | 11.6 | 4.6 | 84.3 | 4.1 |

| 1949 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 0.2 | 79.0 | -0.6 |

| 1950s | |||||

| 1950 | 14.4 | 15.6 | -1.1 | 80.2 | 8.7 |

| 1951 | 16.1 | 14.2 | 1.9 | 66.9 | 8.0 |

| 1952 | 19.0 | 19.4 | -0.4 | 61.6 | 4.1 |

| 1953 | 18.7 | 20.4 | -1.7 | 58.6 | 4.7 |

| 1954 | 18.5 | 18.8 | -0.3 | 59.5 | -0.6 |

| 1955 | 16.5 | 17.3 | -0.8 | 57.2 | 7.1 |

| 1956 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 0.9 | 52.0 | 2.1 |

| 1957 | 17.7 | 17.0 | 0.8 | 48.6 | 2.1 |

| 1958 | 17.3 | 17.9 | -0.6 | 49.2 | -0.7 |

| 1959 | 16.2 | 18.8 | -2.6 | 47.9 | 6.9 |

| 1960s | |||||

| 1960 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 0.1 | 45.6 | 2.6 |

| 1961 | 17.8 | 18.4 | -0.6 | 45.0 | 2.6 |

| 1962 | 17.6 | 18.8 | -1.3 | 43.7 | 6.1 |

| 1963 | 17.8 | 18.6 | -0.8 | 42.4 | 4.4 |

| 1964 | 17.6 | 18.5 | -0.9 | 40.0 | 5.8 |

| 1965 | 16.4 | 16.6 | -0.2 | 36.7 | 6.5 |

| 1966 | 16.7 | 17.2 | -0.5 | 33.7 | 6.6 |

| 1967 | 17.8 | 18.8 | -1.0 | 31.8 | 2.7 |

| 1968 | 17.0 | 19.8 | -2.8 | 32.2 | 4.9 |

| 1969 | 19.0 | 18.7 | 0.3 | 28.3 | 3.1 |

| 1970s | |||||

| 1970 | 18.4 | 18.6 | -0.3 | 27.0 | 0.2 |

| 1971 | 16.7 | 18.8 | -2.1 | 27.1 | 3.3 |

| 1972 | 17.0 | 18.9 | -1.9 | 26.4 | 5.3 |

| 1973 | 17.0 | 18.1 | -1.1 | 25.1 | 5.6 |

| 1974 | 17.7 | 18.1 | -0.4 | 23.1 | -0.5 |

| 1975 | 17.3 | 20.6 | -3.3 | 24.5 | -0.2 |

| 1976 | 16.6 | 20.8 | -4.1 | 26.7 | 5.4 |

| 1977 | 17.5 | 20.2 | -2.6 | 27.1 | 4.6 |

| 1978 | 17.5 | 20.1 | -2.6 | 26.6 | 5.5 |

| 1979 | 18.0 | 19.6 | -1.6 | 24.9 | 3.2 |

| 1980s | |||||

| 1980 | 18.5 | 21.1 | -2.6 | 25.5 | -0.3 |

| 1981 | 19.1 | 21.6 | -2.5 | 25.2 | 2.5 |

| 1982 | 18.6 | 22.5 | -3.9 | 27.9 | -1.8 |

| 1983 | 17.0 | 22.8 | -5.9 | 32.1 | 4.6 |

| 1984 | 16.9 | 21.5 | -4.7 | 33.1 | 7.2 |

| 1985 | 17.2 | 22.2 | -5.0 | 35.3 | 4.2 |

| 1986 | 17.0 | 21.8 | -4.9 | 38.4 | 3.5 |

| 1987 | 17.9 | 21.0 | -3.1 | 39.5 | 3.5 |

| 1988 | 17.6 | 20.6 | -3.0 | 39.8 | 4.2 |

| 1989 | 17.8 | 20.5 | -2.7 | 39.3 | 3.7 |

| 1990s | |||||

| 1990 | 17.4 | 21.2 | -3.7 | 40.8 | 1.9 |

| 1991 | 17.3 | 21.7 | -4.4 | 44.0 | -0.1 |

| 1992 | 17.0 | 21.5 | -4.5 | 46.6 | 3.5 |

| 1993 | 17.0 | 20.7 | -3.8 | 47.8 | 2.8 |

| 1994 | 17.5 | 20.3 | -2.8 | 47.7 | 4.0 |

| 1995 | 17.8 | 20.0 | -2.2 | 47.5 | 2.7 |

| 1996 | 18.2 | 19.6 | -1.3 | 46.8 | 3.8 |

| 1997 | 18.6 | 18.9 | -0.3 | 44.5 | 4.4 |

| 1998 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 0.8 | 41.6 | 4.5 |

| 1999 | 19.2 | 17.9 | 1.3 | 38.2 | 4.8 |

| 2000s | |||||

| 2000 | 20.0 | 17.6 | 2.3 | 33.6 | 4.1 |

| 2001 | 18.8 | 17.6 | 1.2 | 31.4 | 1.0 |

| 2002 | 17.0 | 18.5 | -1.5 | 32.6 | 1.7 |

| 2003 | 15.7 | 19.1 | -3.3 | 34.5 | 2.9 |

| 2004 | 15.6 | 19.0 | -3.4 | 35.5 | 3.8 |

| 2005 | 16.7 | 19.2 | -2.5 | 35.6 | 3.5 |

| 2006 | 17.6 | 19.4 | -1.8 | 35.3 | 2.9 |

| 2007 | 17.9 | 19.1 | -1.1 | 35.2 | 1.9 |

| 2008 | 17.1 | 20.2 | -3.1 | 39.3 | -0.1 |

| 2009 | 14.6 | 24.4 | -9.8 | 52.3 | -2.5 |

| 2010s | |||||

| 2010 | 14.6 | 23.4 | -8.7 | 60.9 | 2.6 |

| 2011 | 15.0 | 23.4 | -8.5 | 65.9 | 1.6 |

| 2012 | 15.3 | 22.1 | -6.8 | 70.4 | 2.2 |

| 2013 | 16.8 | 20.9 | -4.1 | 72.6 | 1.8 |

| 2014 | 17.5 | 20.3 | -2.8 | 74.1 | 2.5 |

| 2015 | 18.1 | 20.5 | -2.4 | 72.9 | 2.9 |

| 2016 | 17.7 | 20.9 | -3.2 | 76.7 | 1.6 |

| 2017 | 17.3 | 20.8 | -3.5 | 76.5 | 2.2 |

Sources: CBO, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#2

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3 Office of Management and Budget. 2011. Historical Tables. Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2011. Washington, DC: OMB. CBO (2012JanBEO). CBO (2012Jan31). CBO (2012AugBEO). CBO (2013BEOFeb5). CBO2013HBDFeb5), CBO (2013Aug12). CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, Historical budget data—April 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14, 2014. Congressional Budget Office, August 2014 baseline: an update to the budget and economic outlook: 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 27, 2014. CBO, Historical Budget Data, January 2015 Baseline from Budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Jan 26.

Table IIA1-6 of the US, Congressional Budget Office, provides 40-Year averages of revenues and outlays before and after revision of the US National Income Accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. This precedes the revision since 1929 in Sep 2018 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2018/09/revision-of-united-states-national.html).

Table IIA1-6, US, Congressional Budget Office, 40-Year Averages of Revenues and Outlays Before and After Update of the US National Income Accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, % of GDP

| Before Update | After Update | |

| Revenues | ||

| Individual Income Taxes | 8.2 | 7.9 |

| Social Insurance Taxes | 6.2 | 6.0 |

| Corporate Income Taxes | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Other | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Total Revenues | 17.9 | 17.4 |

| Outlays | ||

| Mandatory | 10.2 | 9.9 |

| Discretionary | 8.6 | 8.4 |

| Net Interest | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Total Outlays | 21.0 | 20.4 |

| Deficit | -3.1 | -3.0 |

| Debt Held by the Public | 39.2 | 38.0 |

Source: CBO (2013Aug12Av). Kim Kowaleski and Amber Marcellino

Table IIA1-7 provides the latest exercise by the CBO (CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6)

of projecting the fiscal accounts of the US. Table IIA1-7 extends data back to 1995 with the projections of the CBO from 2018 to 2028, using the new estimates of the Bureau of Economic Analysis of US GDP (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Budget analysis in the US uses a ten-year horizon. The significant event in the data before 2011 is the budget surpluses from 1998 to 2001, from 0.8 percent of GDP in 1998 to 2.3 percent of GDP in 2000 and 1.2 percent of GDP in 2001. Debt held by the public fell from 47.5 percent of GDP in 1995 to 31.4 percent of GDP in 2001. The deb/GDP ratio would rise in the projection from actual 76.5 percent in 2018 to 96.2 percent in 2028.

Table IIA1-7, US, CBO Baseline Budget Outlook 2018-2028

| Out | Out | Deficit | Deficit | Debt | Debt | |

| 1995 | 1,516 | 20.0 | -164 | -2.2 | 3,604 | 47.5 |

| 1996 | 1,560 | 19.6 | -107 | -1.3 | 3,734 | 46.8 |

| 1997 | 1,601 | 18.9 | -22 | -0.3 | 3,772 | 44.5 |

| 1998 | 1,652 | 18.5 | +69 | +0.8 | 3,721 | 41.6 |

| 1999 | 1,702 | 17.9 | +126 | +1.3 | 3,632 | 38.2 |

| 2000 | 1,789 | 17.6 | +236 | +2.3 | 3,410 | 33.6 |

| 2001 | 1,863 | 17.6 | +128 | +1.2 | 3,320 | 31.4 |

| 2002 | 2,011 | 18.5 | -158 | -1.5 | 3,540 | 32.6 |

| 2003 | 2,160 | 19.1 | -378 | -3.3 | 3,913 | 34.5 |

| 2004 | 2,293 | 19.0 | -413 | -3.4 | 4,295 | 35.5 |

| 2005 | 2,472 | 19.2 | -318 | -2.5 | 4,592 | 35.6 |

| 2006 | 2,655 | 19.4 | -248 | -1.8 | 4,829 | 35.3 |

| 2007 | 2,729 | 19.1 | -161 | -1.1 | 5,035 | 35.2 |

| 2008 | 2,983 | 20.2 | -459 | -3.1 | 5,803 | 39.3 |

| 2009 | 3,518 | 24.4 | -1,413 | -9.8 | 7,545 | 52.3 |

| 2010 | 3,457 | 23.4 | -1,294 | -8.7 | 9,019 | 60.9 |

| 2011 | 3,603 | 23.4 | -1,300 | -8.5 | 10,128 | 65.9 |

| 2012 | 3,537 | 22.1 | -1,087 | -6.8 | 11,281 | 70.4 |

| 2013 | 3,455 | 20.9 | -680 | -4.1 | 11,983 | 72.6 |

| 2014 | 3,506 | 20.3 | -485 | -2.8 | 12,780 | 74.1 |

| 2015 | 3,688 | 20.5 | -438 | -2.4 | 13,117 | 72.9 |

| 2016 | 3,853 | 20.9 | -585 | -3.2 | 14,168 | 76.7 |

| 2017 | 3,982 | 20.8 | -665 | -3.5 | 14,665 | 76.5 |

| 2018 | 4,142 | 20.6 | -804 | -4.0 | 15,688 | 78.0 |

| 2019 | 4,470 | 21.2 | -981 | -4.6 | 16,762 | 79.3 |

| 2020 | 4,685 | 21.3 | -1,008 | -4.6 | 17,827 | 80.9 |

| 2021 | 4,949 | 21.6 | -1,123 | -4.9 | 18,998 | 83.1 |

| 2022 | 5,288 | 22.3 | -1,276 | -5.4 | 20,319 | 85.7 |

| 2023 | 5,500 | 22.3 | -1,273 | -5.2 | 21,638 | 87.9 |

| 2024 | 5,688 | 22.2 | -1,244 | -4.9 | 22,932 | 89.6 |

| 2025 | 6,015 | 22.6 | -1,352 | -5.1 | 24,338 | 91.5 |

| 2026 | 6,322 | 22.9 | -1,320 | -4.8 | 25,715 | 93.1 |

| 2027 | 6,615 | 23.1 | -1,316 | -4.6 | 27,087 | 94.5 |

| 2028 | 7,046 | 23.6 | -1,526 | -5.1 | 28,671 | 96.2 |

| 2019 to 2023 | 24,893 | 21.8 | -5,660 | -4.9 | NA | NA |

| 2019 | 56,580 | 22.4 | -12,418 | -4.9 | NA | NA |

Note: Out = outlays

Sources: CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

CBO (2011AugBEO); Office of Management and Budget. 2011. Historical Tables. Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2011. Washington, DC: OMB; CBO. 2011JanBEO. Budget and Economic Outlook. Washington, DC, Jan. CBO. 2012AugBEO. Budget and Economic Outlook. Washington, DC, Aug 22. CBO. 2012Jan31. Historical budget data. Washington, DC, Jan 31. CBO. 2012NovCDR. Choices for deficit reduction. Washington, DC. Nov. CBO. 2013HBDFeb5. Historical budget data—February 2013 baseline projections. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 5. CBO. 2013HBDFeb5. Historical budget data—February 2013 baseline projections. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 5. CBO (2013Sep11). CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 2014. CBO, Historical budget data—April 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14, 2014. CBO, Updated Budget Projections: 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14, 2014.

Congressional Budget Office, August 2014 baseline: an update to the budget and economic outlook: 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 27, 2014. CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jan 26, 2015. CBO. 2015. An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 25. CBO, Updated budget projections: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Mar 2016. CBO, An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Aug 23, 2016.

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#2

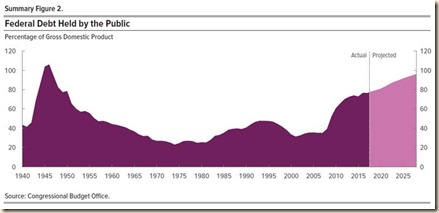

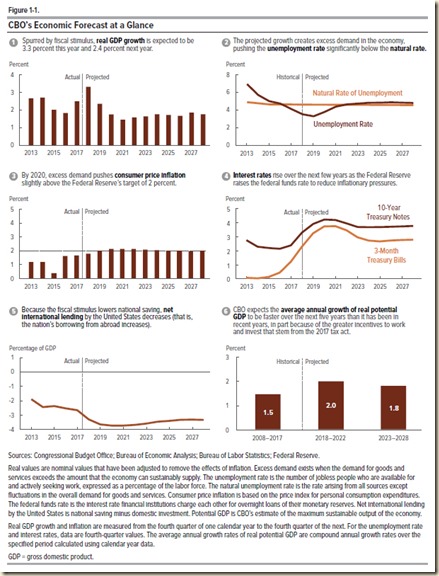

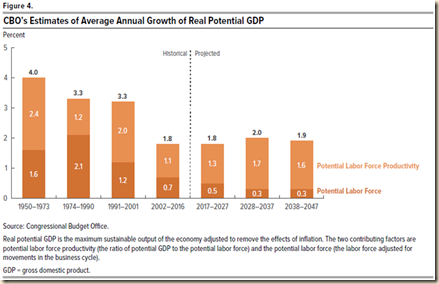

Chart IIA1-BEO2018 provides the federal debt held by the public as percentage of GDP from 1940 to 2018. The projection shows rapid increases in the ratio toward 100 percent of GDP in 2028.

Chart IIA1-BEO2018, Federal Debt Held by the Public 1940-2018,

Source: CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

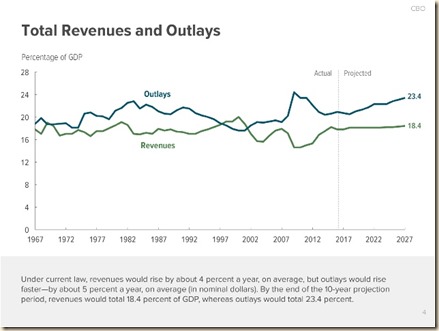

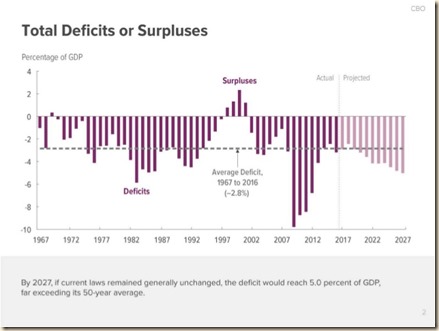

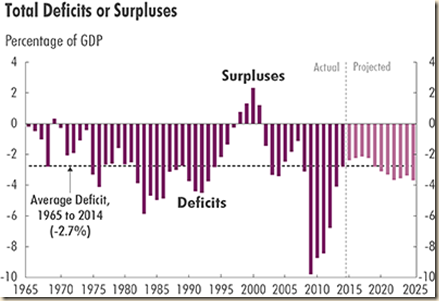

Chart IIA1-1 of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides the deficits of the US as percent of GDP from 1967 to 2016 followed on the right with the projections of the CBO in Jan 2017. Large deficits from 2009 to 2013, all above the average from 1965 to 2016, doubled the debt held by the public. Fiscal adjustment is now more challenging with rigidities in revenues and expenditures. The projections of the CBO in Jan 2017 for the years from 2017 to 2027 show lower deficits in proportion of GDP in the initial years that eventually become larger than the average in the second half of the ten-year window.

Chart IIA1-1A, US, Actual Average and Projected Revenues and Outlays

Source: CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2017-2027. Washington, DC, Jan 24, 2017 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52370

Table IIA1-8 provides baseline CBO projections of federal revenues, outlays, deficit and debt as percent of GDP. The adjustment depends on increasing revenues from 15.0 percent of GDP in 2011 and 17.3 percent in 2017 to 18.5 percent of GDP in 2028, which is above the average of 17.4 percent of GDP from 1968 to 2017. Outlays fall from 23.4 percent of GDP in 2011 to 20.8 percent of GDP in 2017, increasing to 23.6 percent of GDP in 2028, which is much higher than 20.3 percent on average from 1968 to 2018. The last row of Table IIA1-8 provides the CBO estimates of averages for 1968 to 2017 of 17.4 percent for revenues/GDP, 20.3 percent for outlays/GDP and 40.7 percent for debt/GDP. The debt/GDP ratio increases to 96.2 percent of GDP in 2028. The United States faces tough adjustment of its fiscal accounts. There is an additional source of pressure on financing the current account deficit of the balance of payments.

| Revenues | Outlays | Deficit | Debt | |

| 2011 | 15.0 | 23.4 | -8.5 | 65.9 |

| 2012 | 15.3 | 22.1 | -6.8 | 70.4 |

| 2013 | 16.8 | 20.9 | -4.1 | 72.6 |

| 2014 | 17.5 | 20.3 | -2.8 | 74.1 |

| 2015 | 18.1 | 20.5 | -2.4 | 72.9 |

| 2016 | 17.7 | 20.9 | -3.2 | 76.7 |

| 2017 | 17.3 | 20.8 | -3.5 | 76.5 |

| 2018 | 16.6 | 20.6 | -4.0 | 78.0 |

| 2019 | 16.5 | 21.2 | -4.6 | 79.3 |

| 2020 | 16.7 | 21.3 | -4.6 | 80.9 |

| 2021 | 16.7 | 21.6 | -4.9 | 83.1 |

| 2022 | 16.9 | 22.3 | -5.4 | 85.7 |

| 2023 | 17.2 | 22.3 | -5.2 | 87.9 |

| 2024 | 17.4 | 22.2 | -4.9 | 89.6 |

| 2025 | 17.5 | 22.6 | -5.1 | 91.5 |

| 2026 | 18.1 | 22.9 | -4.8 | 93.1 |

| 2027 | 18.5 | 23.1 | -4.6 | 94.5 |

| 2028 | 18.5 | 23.6 | -5.1 | 96.2 |

| Total 2019-2023 | 16.8 | 21.8 | -4.9 | NA |

| Total 2019-2028 | 17.5 | 22.4 | -4.9 | NA |

| Average | 17.4 | 20.3 | -2.9 | 40.7 |

Source: CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2018 to 2028. Washington, DC, Apr 9, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651

CBO (2012AugBEO). CBO (2012NovCDR). CBO (2013BEOFeb5). CBO 2013HBDFeb5), CBO (2013Sep11), CBO (2013Aug12Av). Kim Kowaleski and Amber Marcellino. CBO, Historical Budget Data—February 2014, Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb. CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Feb 2014. CBO, Historical budget data—April 2014 release. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14, 2014. CBO, Updated Budget Projections: 2014 to 2024. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Apr 14, 2014. CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jan 26, 2015. CBO. 2015. An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 25. CBO, Updated budget projections: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Mar 2016. CBO, An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2016 to 2026. Washington, DC, Aug 23, 2016.

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#2

Chart IA1-2, Congressional Budget Office, Total Deficits of Surpluses, Percent of GDP

Source: CBO, The budget and economic outlook: 2017-2027. Washington, DC, Jan 24, 2017 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52370

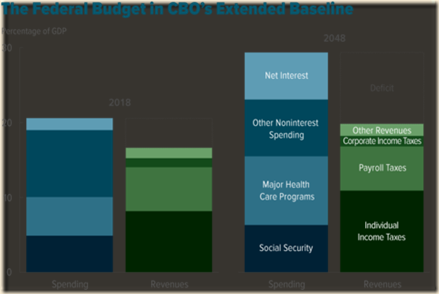

Table IIA1-9 provides the long-term budget outlook of the CBO for 2018, 2028 and 2048. Revenues increase from 16.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 19.8 percent in 2047. The growing stock of debt raises net interest spending from 1.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 3.8 percent in 2028 and 6.3 percent 2048. Total spending increases from 20.6 percent of GDP in 2018 to 29.3 percent in 2048. Federal debt held by the public rises to 152.0 percent of GDP in 2048. US fiscal affairs are in an unsustainable path with tough rigidities in spending and revenues.

Table IIA1-9, Congressional Budget Office, Long-term Budget Outlook, % of GDP

| 2018 | 2028 | 2048 | |

| Revenues | 16.6 | 18.5 | 19.8 |

| Total Noninterest Spending | 19.0 | 20.6 | 23.1 |

| Social Security | 4.9 | 6.0 | 6.3 |

| Medicare | 2.9 | 4.2 | 5.9 |

| Medicaid, CHIP and Exchange Subsidies | 2.3 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| Other | 8.9 | 7.9 | 7.6 |

| Net Interest | 1.6 | 3.1 | 6.3 |

| Total Spending | 20.6 | 23.6 | 29.3 |

| Revenues Minus Total Noninterest Spending | -2.4 | -2.1 | -3.3 |

| Revenues Minus Total Spending | -3.9 | -5.1 | -9.5 |

| Federal Debt Held by the Public | 78.0 | 96.0 | 152.0 |

Source: CBO, The 2018 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Jun 26, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53919

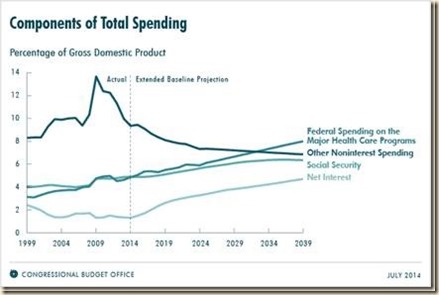

Chart IIA1-LTB18 of the CBO illustrates the rigidity of major health care programs and social security with limited upside potential in taxes.

Chart IIA1-LTB18, The extended baseline of CBO 2018-2048,

Source: CBO, The 2018 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Jun 26, 2018 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53919

Chart IIA1-3 provides actual federal debt held by the public as percent of GDP from 1790 to 2016 and projected by the CBO (2017Mar30) from 2017 to 2047. The ratio of debt to GDP climbed from 42.3 percent in 1941 to a peak of 108.7 percent in 1946 because of the Second World War. The ratio of debt to GDP declined to 80.2 percent in 1950 and 66.9 percent in 1951 because of unwinding war effort, economy growing to capacity and less rigid mandatory expenditures. The ratio of debt to GDP of 77.0 percent in 2016 is the highest in the United States since 1950. The CBO (2015BEOJun17) projects the ratio of debt of GDP of the United States to reach 150.0 percent in 2047, which will be more than double the average ratio of 39.7 percent in 1973-2016. The misleading debate on the so-called “fiscal cliff” has disguised the unsustainable path of United States fiscal affairs.

Chart IIA1-3, Congressional Budget Office, Federal Debt Held by the Public, Extended Baseline Projection, % of GDP

Source: CBO, The 2017 Long-term Budget Outlook. Washington, DC, Mar 30, 2017 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52480 https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#1

Chart IIIA1-4 of the Congressional Budget Office provides actual and extended baseline projections of federal debt held by the public, spending and revenues. The excess of spending over revenues increases from 2.7 percent in 2015 to 3.8 percent in 2025 and 5.9 percent in 2040. Federal debt held by the public rises from 74.0 percent of GDP in 2015 to 78.0 percent of GDP in 2025 and 103 percent of GDP in 2040.

Chart IIA1-4, Congressional Budget Office, Federal Debt Held by the Public, % of GDP

Source: Source: CBO (2015Jun15). The 2015 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jun 16.

Chart IIA1-5 of the Congressional Budget Office provides actual and baseline projections of components of federal spending, illustrating the rigidity of US federal government spending. The combined spending in social security, Medicare and Medicaid increases from 10.1 percent of GDP in 2015 to 14.2 percent of GDP in 2040. Interest spending on a rising federal debt increases from 1.3 percent of GDP in 2015 to 4.3 percent of GDP in 2040.

Chart IIA1-5, Congressional Budget Office, Actual and Extended Baseline Projections of Components of Total Spending, % of GDP

Source: CBO (2014Jul25). The 2014 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jul 25.

Chart IIA1-6 of the Congressional Budget Office provides similar rigidity in the components of federal revenues. Individual income taxes increase from 8.0 percent of GDP in 2014 to 10.5 percent of GDP in 2039. Corporate income taxes decrease from 2.0 percent of GDP in 2014 to 1.8 percent of GDP in 2039. Payroll (social insurance) taxes decrease from 6.0 percent of GDP in 2014 to 5.7 percent of GDP in 2039. Other revenue sources decrease from 1.5 percent of GDP in 2014 to 1.4 percent of GDP in 2039. There is limited space for reduction of expenditures and increases of revenue.

Chart IIA1-6, Congressional Budget Office, Actual and Extended Baseline Projections of Components of Total Revenue, % of GDP

Source: CBO (2014Jul25). The 2014 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jul 25.

Chart X, Congressional Budget Office, Total Deficits of Surpluses, Percent of GDP

Source: CBO. 2015. An update to the budget and economic outlook: 2015 to 2025. Washington, DC, CBO, Aug 25.

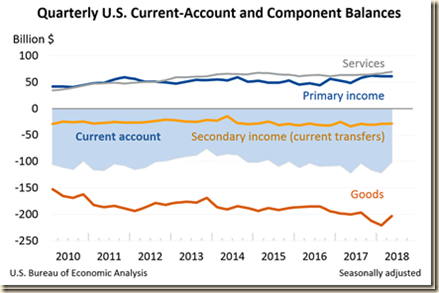

The current account of the US balance of payments is in Table VI-3A for IIQ2017 and IIQ2018. The Bureau of Economic Analysis analyzes as follows (https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2018-09/trans218.pdf):

“The U.S. current-account deficit decreased to $101.5 billion (preliminary) in the second quarter of 2018 from $121.7 billion (revised) in the first quarter of 2018, according to statistics released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The deficit was 2.0 percent of current-dollar gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter, down from 2.4 percent in the first quarter.”

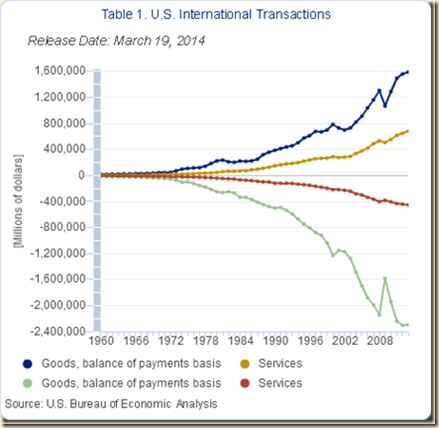

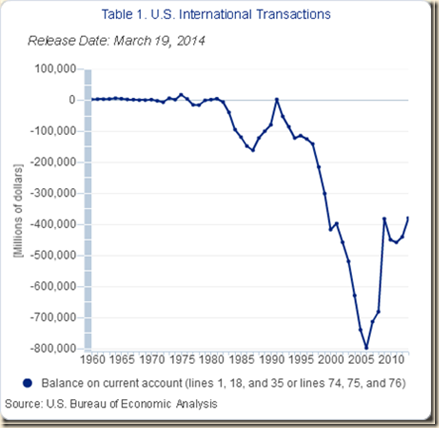

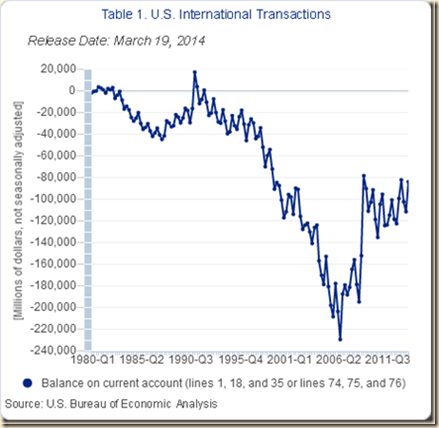

The US has a large deficit in goods or exports less imports of goods but it has a surplus in services that helps to reduce the trade account deficit or exports less imports of goods and services. The current account deficit of the US not seasonally adjusted decreased from $133.9 billion in IIQ2017 to $118.7 billion in IIQ2018. The current account deficit seasonally adjusted at annual rate decreased from 2.5 percent of GDP in IIQ2017 to 2.4 percent of GDP in IQ2018, decreasing to 2.0 percent of GDP in IIQ2018. The ratio of the current account deficit to GDP has stabilized below 3 percent of GDP compared with much higher percentages before the recession but is combined now with much higher imbalance in the Treasury budget (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 183-94, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 167-71). There is still a major challenge in the combined deficits in current account and in federal budgets.

Table VI-3A, US, Balance of Payments, Millions of Dollars NSA

| IIQ2017 | IIQ2018 | Difference | |

| Goods Balance | -203,897 | -210,363 | -6,466 |

| X Goods | 385,964 | 429,368 | 11.2 ∆% |

| M Goods | -589,861 | -639,730 | 8.5 ∆% |

| Services Balance | 54,113 | 58,503 | 4,390 |

| X Services | 192,814 | 203,197 | 5.4 ∆% |

| M Services | -138,700 | -144,694 | 4.3 ∆% |

| Balance Goods and Services | -149,783 | -151,860 | -2,077 |

| Exports of Goods and Services and Income Receipts | 837,799 | 926,818 | 89,019 |

| Imports of Goods and Services and Income Payments | -971,721 | -1,045,502 | -73,781 |

| Current Account Balance | -133,921 | -118,684 | 15,237 |

| % GDP | IIQ2017 | IIQ2018 | IQ2018 |

| 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

X: exports; M: imports

Balance on Current Account = Exports of Goods and Services – Imports of Goods and Services and Income Payments

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm#bop

Chart VI-3B, US, Current Account and Components Balances, Quarterly SA

Source: https://www.bea.gov/news/2018

“Imagine that fiscal policy dominates monetary policy. The fiscal authority independently sets its budgets, announcing all current and future deficits and surpluses and thus determining the amount of revenue that must be raised through bond sales and seignorage. Under this second coordination scheme, the monetary authority faces the constraints imposed by the demand for government bonds, for it must try to finance with seignorage any discrepancy between the revenue demanded by the fiscal authority and the amount of bonds that can be sold to the public. Suppose that the demand for government bonds implies an interest rate on bonds greater than the economy’s rate of growth. Then if the fiscal authority runs deficits, the monetary authority is unable to control either the growth rate of the monetary base or inflation forever. If the principal and interest due on these additional bonds are raised by selling still more bonds, so as to continue to hold down the growth of base money, then, because the interest rate on bonds is greater than the economy’s growth rate, the real stock of bonds will growth faster than the size of the economy. This cannot go on forever, since the demand for bonds places an upper limit on the stock of bonds relative to the size of the economy. Once that limit is reached, the principal and interest due on the bonds already sold to fight inflation must be financed, at least in part, by seignorage, requiring the creation of additional base money.”

The alternative fiscal scenario of the CBO (2012NovCDR, 2013Sep17) resembles an economic world in which eventually the placement of debt reaches a limit of what is proportionately desired of US debt in investment portfolios. This unpleasant environment is occurring in various European countries.

The current real value of government debt plus monetary liabilities depends on the expected discounted values of future primary surpluses or difference between tax revenue and government expenditure excluding interest payments (Cochrane 2011Jan, 27, equation (16)). There is a point when adverse expectations about the capacity of the government to generate primary surpluses to honor its obligations can result in increases in interest rates on government debt.

First, Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic. Fiscal policy is described by Sargent and Wallace (1981, 3, equation 1) as a time sequence of D(t), t = 1, 2,…t, …, where D is real government expenditures, excluding interest on government debt, less real tax receipts. D(t) is the real deficit excluding real interest payments measured in real time t goods. Monetary policy is described by a time sequence of H(t), t=1,2,…t, …, with H(t) being the stock of base money at time t. In order to simplify analysis, all government debt is considered as being only for one time period, in the form of a one-period bond B(t), issued at time t-1 and maturing at time t. Denote by R(t-1) the real rate of interest on the one-period bond B(t) between t-1 and t. The measurement of B(t-1) is in terms of t-1 goods and [1+R(t-1)] “is measured in time t goods per unit of time t-1 goods” (Sargent and Wallace 1981, 3). Thus, B(t-1)[1+R(t-1)] brings B(t-1) to maturing time t. B(t) represents borrowing by the government from the private sector from t to t+1 in terms of time t goods. The price level at t is denoted by p(t). The budget constraint of Sargent and Wallace (1981, 3, equation 1) is:

D(t) = {[H(t) – H(t-1)]/p(t)} + {B(t) – B(t-1)[1 + R(t-1)]} (1)

Equation (1) states that the government finances its real deficits into two portions. The first portion, {[H(t) – H(t-1)]/p(t)}, is seigniorage, or “printing money.” The second part,

{B(t) – B(t-1)[1 + R(t-1)]}, is borrowing from the public by issue of interest-bearing securities. Denote population at time t by N(t) and growing by assumption at the constant rate of n, such that:

N(t+1) = (1+n)N(t), n>-1 (2)

The per capita form of the budget constraint is obtained by dividing (1) by N(t) and rearranging:

B(t)/N(t) = {[1+R(t-1)]/(1+n)}x[B(t-1)/N(t-1)]+[D(t)/N(t)] – {[H(t)-H(t-1)]/[N(t)p(t)]} (3)

On the basis of the assumptions of equal constant rate of growth of population and real income, n, constant real rate of return on government securities exceeding growth of economic activity and quantity theory equation of demand for base money, Sargent and Wallace (1981) find that “tighter current monetary policy implies higher future inflation” under fiscal policy dominance of monetary policy. That is, the monetary authority does not permanently influence inflation, lowering inflation now with tighter policy but experiencing higher inflation in the future.

Second, Unpleasant Fiscal Arithmetic. The tool of analysis of Cochrane (2011Jan, 27, equation (16)) is the government debt valuation equation:

(Mt + Bt)/Pt = Et∫(1/Rt, t+τ)st+τdτ (4)

Equation (4) expresses the monetary, Mt, and debt, Bt, liabilities of the government, divided by the price level, Pt, in terms of the expected value discounted by the ex-post rate on government debt, Rt, t+τ, of the future primary surpluses st+τ, which are equal to Tt+τ – Gt+τ or difference between taxes, T, and government expenditures, G. Cochrane (2010A) provides the link to a web appendix demonstrating that it is possible to discount by the ex post Rt, t+τ. The second equation of Cochrane (2011Jan, 5) is:

MtV(it, ·) = PtYt (5)

Conventional analysis of monetary policy contends that fiscal authorities simply adjust primary surpluses, s, to sanction the price level determined by the monetary authority through equation (5), which deprives the debt valuation equation (4) of any role in price level determination. The simple explanation is (Cochrane 2011Jan, 5):

“We are here to think about what happens when [4] exerts more force on the price level. This change may happen by force, when debt, deficits and distorting taxes become large so the Treasury is unable or refuses to follow. Then [4] determines the price level; monetary policy must follow the fiscal lead and ‘passively’ adjust M to satisfy [5]. This change may also happen by choice; monetary policies may be deliberately passive, in which case there is nothing for the Treasury to follow and [4] determines the price level.”

An intuitive interpretation by Cochrane (2011Jan 4) is that when the current real value of government debt exceeds expected future surpluses, economic agents unload government debt to purchase private assets and goods, resulting in inflation. If the risk premium on government debt declines, government debt becomes more valuable, causing a deflationary effect. If the risk premium on government debt increases, government debt becomes less valuable, causing an inflationary effect.

There are multiple conclusions by Cochrane (2011Jan) on the debt/dollar crisis and Global recession, among which the following three:

(1) The flight to quality that magnified the recession was not from goods into money but from private-sector securities into government debt because of the risk premium on private-sector securities; monetary policy consisted of providing liquidity in private-sector markets suffering stress

(2) Increases in liquidity by open-market operations with short-term securities have no impact; quantitative easing can affect the timing but not the rate of inflation; and purchase of private debt can reverse part of the flight to quality

(3) The debt valuation equation has a similar role as the expectation shifting the Phillips curve such that a fiscal inflation can generate stagflation effects similar to those occurring from a loss of anchoring expectations.

This analysis suggests that there may be a point of saturation of demand for United States financial liabilities without an increase in interest rates on Treasury securities. A risk premium may develop on US debt. Such premium is not apparent currently because of distressed conditions in the world economy and international financial system. Risk premiums are observed in the spread of bonds of highly indebted countries in Europe relative to bonds of the government of Germany.

The issue of global imbalances centered on the possibility of a disorderly correction (Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), Globalization and the State Vol. II (2008b) 183-94, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 167-71). Such a correction has not occurred historically but there is no argument proving that it could not occur. The need for a correction would originate in unsustainable large and growing United States current account deficits (CAD) and net international investment position (NIIP) or excess of financial liabilities of the US held by foreigners net relative to financial liabilities of foreigners held by US residents. The IMF estimated that the US could maintain a CAD of two to three percent of GDP without major problems (Rajan 2004). The threat of disorderly correction is summarized by Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 15):

“It is possible that foreigners may be unwilling to increase their positions in US financial assets at prevailing interest rates. An exit out of the dollar could cause major devaluation of the dollar. The depreciation of the dollar would cause inflation in the US, leading to increases in American interest rates. There would be an increase in mortgage rates followed by deterioration of real estate values. The IMF has simulated that such an adjustment would cause a decline in the rate of growth of US GDP to 0.5 percent over several years. The decline of demand in the US by four percentage points over several years would result in a world recession because the weakness in Europe and Japan could not compensate for the collapse of American demand. The probability of occurrence of an abrupt adjustment is unknown. However, the adverse effects are quite high, at least hypothetically, to warrant concern.”

The United States could be moving toward a situation typical of heavily indebted countries, requiring fiscal adjustment and increases in productivity to become more competitive internationally. The CAD and NIIP of the United States are not observed in full deterioration because the economy is well below trend. There are two complications in the current environment relative to the concern with disorderly correction in the first half of the past decade. In the release of Jun 14, 2013, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/transactions/2013/pdf/trans113.pdf) informs of revisions of US data on US international transactions since 1999:

“The statistics of the U.S. international transactions accounts released today have been revised for the first quarter of 1999 to the fourth quarter of 2012 to incorporate newly available and revised source data, updated seasonal adjustments, changes in definitions and classifications, and improved estimating methodologies.”

The BEA introduced new concepts and methods (http://www.bea.gov/international/concepts_methods.htm) in comprehensive restructuring on Jun 18, 2014 (http://www.bea.gov/international/modern.htm):

“BEA introduced a new presentation of the International Transactions Accounts on June 18, 2014 and will introduce a new presentation of the International Investment Position on June 30, 2014. These new presentations reflect a comprehensive restructuring of the international accounts that enhances the quality and usefulness of the accounts for customers and bring the accounts into closer alignment with international guidelines.”

Table IIA2-3 provides data on the US fiscal and balance of payments imbalances incorporating all revisions and methods. In 2007, the federal deficit of the US was $161 billion corresponding to 1.1 percent of GDP while the Congressional Budget Office estimates the federal deficit in 2012 at $1087 billion or 6.8 percent of GDP. The estimate of the deficit for 2013 is $680 billion or 4.1 percent of GDP. The combined record federal deficits of the US from 2009 to 2012 are $5094 billion or 31.6 percent of the estimate of GDP for fiscal year 2012 implicit in the CBO (CBO 2013Sep11) estimate of debt/GDP. The deficits from 2009 to 2012 exceed one trillion dollars per year, adding to $5.094 trillion in four years, using the fiscal year deficit of $1087 billion for fiscal year 2012, which is the worst fiscal performance since World War II. Federal debt in 2007 was $5035 billion, slightly less than the combined deficits from 2009 to 2012 of $5094 billion. Federal debt in 2012 was 70.4 percent of GDP (CBO 2015Jan26) and 72.6 percent of GDP in 2013 (http://www.cbo.gov/). This situation may worsen in the future (CBO 2013Sep17):

“Between 2009 and 2012, the federal government recorded the largest budget deficits relative to the size of the economy since 1946, causing federal debt to soar. Federal debt held by the public is now about 73 percent of the economy’s annual output, or gross domestic product (GDP). That percentage is higher than at any point in U.S. history except a brief period around World War II, and it is twice the percentage at the end of 2007. If current laws generally remained in place, federal debt held by the public would decline slightly relative to GDP over the next several years, CBO projects. After that, however, growing deficits would ultimately push debt back above its current high level. CBO projects that federal debt held by the public would reach 100 percent of GDP in 2038, 25 years from now, even without accounting for the harmful effects that growing debt would have on the economy. Moreover, debt would be on an upward path relative to the size of the economy, a trend that could not be sustained indefinitely.

The gap between federal spending and revenues would widen steadily after 2015 under the assumptions of the extended baseline, CBO projects. By 2038, the deficit would be 6½ percent of GDP, larger than in any year between 1947 and 2008, and federal debt held by the public would reach 100 percent of GDP, more than in any year except 1945 and 1946. With such large deficits, federal debt would be growing faster than GDP, a path that would ultimately be unsustainable.

Incorporating the economic effects of the federal policies that underlie the extended baseline worsens the long-term budget outlook. The increase in debt relative to the size of the economy, combined with an increase in marginal tax rates (the rates that would apply to an additional dollar of income), would reduce output and raise interest rates relative to the benchmark economic projections that CBO used in producing the extended baseline. Those economic differences would lead to lower federal revenues and higher interest payments. With those effects included, debt under the extended baseline would rise to 108 percent of GDP in 2038.”

The most recent CBO long-term budget on Jun 26, 2018 projects US federal debt at 152.0 percent of GDP in 2048 (Congressional Budget Office, The 2018 long-term budget outlook. Washington, DC, Jun 26 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53919).

Table VI-3B, US, Current Account, NIIP, Fiscal Balance, Nominal GDP, Federal Debt and Direct Investment, Dollar Billions and %

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Goods & | -705 | -709 | -384 | -495 | -549 |

| Primary Income | 85 | 130 | 115 | 168 | 211 |

| Secondary Income | -91 | -102 | -104 | -104 | -107 |

| Current Account | -711 | -681 | -373 | -431 | -445 |

| NGDP | 14452 | 14713 | 14449 | 14992 | 15543 |

| Current Account % GDP | -4.9 | -4.6 | -2.6 | -2.9 | -2.9 |

| NIIP | -1279 | -3995 | -2628 | -2512 | -4455 |

| US Owned Assets Abroad | 20705 | 19423 | 19426 | 21767 | 22209 |

| Foreign Owned Assets in US | 21984 | 23418 | 22054 | 24279 | 26664 |

| NIIP % GDP | -8.8 | -27.1 | -18.2 | -16.8 | -28.7 |

| Exports | 2559 | 2742 | 2283 | 2625 | 2983 |

| NIIP % | -50 | -145 | -115 | -95 | -149 |

| DIA MV | 5858 | 3707 | 4945 | 5486 | 5215 |

| DIUS MV | 4134 | 3091 | 3619 | 4099 | 4199 |

| Fiscal Balance | -161 | -459 | -1413 | -1294 | -1300 |

| Fiscal Balance % GDP | -1.1 | -3.1 | -9.8 | -8.7 | -8.5 |

| Federal Debt | 5035 | 5803 | 7545 | 9019 | 10128 |

| Federal Debt % GDP | 35.2 | 39.3 | 52.3 | 60.9 | 65.9 |

| Federal Outlays | 2729 | 2983 | 3518 | 3457 | 3603 |

| ∆% | 2.8 | 9.3 | 17.9 | -1.7 | 4.2 |

| % GDP | 19.1 | 20.2 | 24.4 | 23.4 | 23.4 |

| Federal Revenue | 2568 | 2524 | 2105 | 2163 | 2303 |

| ∆% | 6.7 | -1.7 | -16.6 | 2.7 | 6.5 |

| % GDP | 17.9 | 17.1 | 14.6 | 14.6 | 15.0 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

| Goods & | -537 | -462 | -490 | -500 | -505 |

| Primary Income | 207 | 206 | 210 | 181 | 173 |

| Secondary Income | -97 | -94 | -94 | -115 | -120 |

| Current Account | -426 | -350 | -374 | -434 | -452 |

| NGDP | 16197 | 16785 | 17522 | 18219 | 18707 |

| Current Account % GDP | -2.6 | -2.1 | -2.1 | -2.4 | -2.4 |

| NIIP | -4518 | -5369 | -6945 | -7462 | -8182 |

| US Owned Assets Abroad | 22562 | 24145 | 24883 | 23431 | 24061 |

| Foreign Owned Assets in US | 27080 | 29513 | 31828 | 30892 | 32242 |

| NIIP % GDP | -27.9 | -32.0 | -39.6 | -41.0 | -43.7 |

| Exports | 3096 | 3212 | 3333 | 3173 | 3157 |

| NIIP % | -146 | -167 | -208 | -235 | -259 |

| DIA MV | 5969 | 7121 | 72421 | 7057 | 7422 |

| DIUS MV | 4662 | 5815 | 6370 | 6729 | 7596 |

| Fiscal Balance | -1087 | -680 | -485 | -439 | -585 |

| Fiscal Balance % GDP | -6.8 | -4.1 | -2.8 | -2.4 | -3.2 |

| Federal Debt | 11281 | 11983 | 12780 | 13117 | 14168 |

| Federal Debt % GDP | 70.4 | 72.6 | 74.1 | 72.9 | 76.7 |

| Federal Outlays | 3537 | 3455 | 3506 | 3688 | 3853 |

| ∆% | -1.8 | -2.3 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 4.5 |

| % GDP | 22.1 | 20.9 | 20.3 | 20.5 | 20.9 |

| Federal Revenue | 2450 | 2775 | 3022 | 3250 | 3268 |

| ∆% | 6.4 | 13.3 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 0.6 |

| % GDP | 15.3 | 16.8 | 17.5 | 18.1 | 17.7 |

| 2017 | |||||

| Goods & | -568 | ||||

| Primary Income | 217 | ||||

| Secondary Income | -115 | ||||

| Current Account | -466 | ||||

| NGDP | 19485 | ||||

| Current Account % GDP | 2.4 | ||||

| NIIP | -7725 | ||||

| US Owned Assets Abroad | 27799 | ||||

| Foreign Owned Assets in US | 35524 | ||||

| NIIP % GDP | -39.6 | ||||

| Exports | 3408 | ||||

| NIIP % | -227 | ||||

| DIA MV | 8910 | ||||

| DIUS MV | 8925 | ||||

| Fiscal Balance | -665 | ||||

| Fiscal Balance % GDP | -3.5 | ||||

| Federal Debt | 14666 | ||||

| Federal Debt % GDP | 76.5 | ||||

| Federal Outlays | 3982 | ||||

| ∆% | 3.3 | ||||

| % GDP | 20.8 | ||||

| Federal Revenue | 3316 | ||||

| ∆% | 1.5 | ||||

| % GDP | 17.3 |

Sources:

Notes: NGDP: nominal GDP or in current dollars; NIIP: Net International Investment Position; DIA MV: US Direct Investment Abroad at Market Value; DIUS MV: Direct Investment in the US at Market Value. There are minor discrepancies in the decimal point of percentages of GDP between the balance of payments data and federal debt, outlays, revenue and deficits in which the original number of the CBO source is maintained. See Bureau of Economic Analysis, US International Economic Accounts: Concepts and Methods. 2014. Washington, DC: BEA, Department of Commerce, Jun 2014 http://www.bea.gov/international/concepts_methods.htm These discrepancies do not alter conclusions. Budget http://www.cbo.gov/

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#6

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#3

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#2

https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data#2 Balance of Payments and NIIP http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm#bop Gross Domestic Product, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table VI-3C provides quarterly estimates NSA of the external imbalance of the United States. The current account deficit seasonally adjusted at 2.5 percent of GDP in IIQ2017 decreases to 2.1 percent in IIIQ2017. The current account deficit increased to 2.3 percent in IVQ2017. The current account deficit increased to 2.4 percent in IQ2018. The current account deficit decreases to 2.0 percent in IIQ2018. The absolute value of the net international investment position decreases from minus $7.9 trillion in IIQ2017 to minus $7.6 trillion in IIIQ2017. The absolute value of the net international investment position increased to $7.7 trillion in IVQ2017. The absolute value of the net international investment position stabilizes at $7.7 trillion in IQ2018. The absolute value of the net international investment position stabilizes to $7.7 trillion in IQ2018. The absolute value of the net international investment position deteriorates to $8.6 trillion in IIQ2018. The BEA explains as follows (https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2018-09/intinv218.pdf):

“The U.S. net international investment position decreased to −$8,638.5 billion (preliminary) at the end of the second quarter of 2018 from −$7,747.3 billion (revised) at the end of the first quarter, according to statistics released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). The $891.2 billion decrease reflected a $587.8 billion decrease in U.S. assets and a $303.4 billion increase in U.S. liabilities (table 1).”

The BEA explains further (https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2018-09/intinv218.pdf):

“• Assets excluding financial derivatives decreased $575.2 billion to $25,485.2 billion. The decrease resulted from financial transactions of −$163.6 billion and other changes in position of −$411.6 billion (table A).

o Financial transactions were driven by net U.S. liquidation of other investment assets, mostly reflecting net foreign repayment of loans.

o Financial transactions also reflected net U.S. withdrawal of direct investment assets as a result of U.S. parent repatriation of previously reinvested earnings. For more information, see the box “Effects of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on U.S. Direct Investment Assets.”

o Other changes in position were driven by exchange-rate changes, as major foreign currencies depreciated against the U.S. dollar, lowering the value of foreign-currencydenominated assets in dollar terms. The decrease from exchange-rate changes was partly offset by foreign equity price increases that raised the equity value of portfolio investment and direct investment assets.

• Financial derivatives decreased $12.6 billion to $1,578.5 billion, mostly reflecting a decrease in single-currency interest rate contracts that was partly offset by an increase in foreign-exchange contracts.”

Table VI-3C, US, Current Account, Net International Investment Position and Direct Investment, Dollar Billions, NSA

| IIQ2017 | IIIQ2017 | IVQ2017 | IQ2018 | IIQ2018 | |

| Goods & | -150 | -142 | -149 | -126 | -152 |

| Primary Income | 48 | 58 | 63 | 62 | 60 |

| Secondary Income | -32 | -30 | -30 | -29 | -27 |

| Current Account | -134 | -114 | -116 | -94 | -119 |

| Current Account % GDP SA | -2.5 | -2.1 | -2.3 | -2.4 | -2.0 |

| NIIP | -7858 | -7625 | -7725 | -7747 | -8638 |

| US Owned Assets Abroad | 26083 | 27124 | 27799 | 27651 | 27064 |

| Foreign Owned Assets in US | -33941 | -34749 | -35524 | -35399 | -35702 |

| DIA MV | 8183 | 8657 | 8910 | 8519 | 8442 |

| DIA MV Equity | 6941 | 7381 | 7646 | 7238 | 7146 |

| DIUS MV | 8207 | 8531 | 8925 | 8834 | 9019 |

| DIUS MV Equity | 6424 | 6714 | 7133 | 7067 | 7266 |

Notes: NIIP: Net International Investment Position; DIA MV: US Direct Investment Abroad at Market Value; DIUS MV: Direct Investment in the US at Market Value. See Bureau of Economic Analysis, US International Economic Accounts: Concepts and Methods. 2014. Washington, DC: BEA, Department of Commerce, Jun 2014 http://www.bea.gov/international/concepts_methods.htm

Chart VI-3C of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis provides the quarterly and annual US net international investment position (NIIP) NSA in billion dollars. The NIIP deteriorated in 2008, improving in 2009-2011 followed by deterioration after 2012. There is improvement in 2017 and deterioration in IQ2018.

Chart VI-3C, US Net International Investment Position, NSA, Billion US Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/intinvnewsrelease.htm

Chart VI-3C1 provides the quarterly NSA NIIP.

Chart VI-3C1, US Net International Investment Position, NSA, Billion US Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/intinvnewsrelease.htm

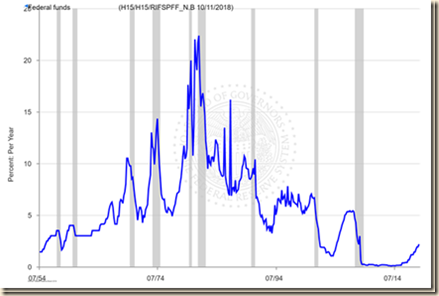

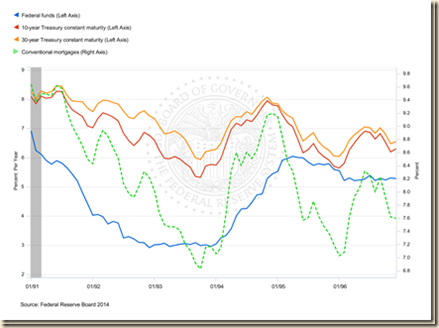

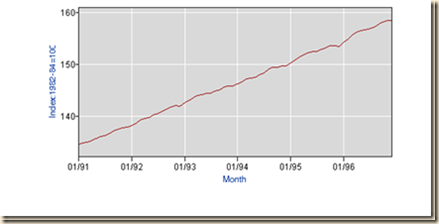

Chart VI-10 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the overnight Fed funds rate on business days from Jul 1, 1954 at 1.13 percent through Jan 10, 1979, at 9.91 percent per year, to Oct 11, 2018, at 2.18 percent per year. US recessions are in shaded areas according to the reference dates of the NBER (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). In the Fed effort to control the “Great Inflation” of the 1970s (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html and Appendix I The Great Inflation; see Taylor 1993, 1997, 1998LB, 1999, 2012FP, 2012Mar27, 2012Mar28, 2012JMCB and http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html), the fed funds rate increased from 8.34 percent on Jan 3, 1979 to a high in Chart VI-10 of 22.36 percent per year on Jul 22, 1981 with collateral adverse effects in the form of impaired savings and loans associations in the United States, emerging market debt and money-center banks (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 72-7; Pelaez 1986, 1987). Another episode in Chart VI-10 is the increase in the fed funds rate from 3.15 percent on Jan 3, 1994, to 6.56 percent on Dec 21, 1994, which also had collateral effects in impairing emerging market debt in Mexico and Argentina and bank balance sheets in a world bust of fixed income markets during pursuit by central banks of non-existing inflation (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 113-5). Another interesting policy impulse is the reduction of the fed funds rate from 7.03 percent on Jul 3, 2000, to 1.00 percent on Jun 22, 2004, in pursuit of equally non-existing deflation (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-85), followed by increments of 25 basis points from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006, raising the fed funds rate to 5.25 percent on Jul 3, 2006 in Chart VI-10. Central bank commitment to maintain the fed funds rate at 1.00 percent induced adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMS) linked to the fed funds rate. Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment but the exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at interest rates close to zero, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV).

The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper with the objective of purchasing default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever-increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and worked with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity because of the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions because the put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4). A final episode in Chart VI-10 is the reduction of the fed funds rate from 5.41 percent on Aug 9, 2007, to 2.97 percent on October 7, 2008, to 0.12 percent on Dec 5, 2008 and close to zero throughout a long period with the final point at 2.18 percent on Oct 11, 2018. Evidently, this behavior of policy would not have occurred had there been theory, measurements and forecasts to avoid these violent oscillations that are clearly detrimental to economic growth and prosperity without inflation. The Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Janet L. Yellen, stated on Jul 10, 2015 that (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150710a.htm):

“Based on my outlook, I expect that it will be appropriate at some point later this year to take the first step to raise the federal funds rate and thus begin normalizing monetary policy. But I want to emphasize that the course of the economy and inflation remains highly uncertain, and unanticipated developments could delay or accelerate this first step. I currently anticipate that the appropriate pace of normalization will be gradual, and that monetary policy will need to be highly supportive of economic activity for quite some time. The projections of most of my FOMC colleagues indicate that they have similar expectations for the likely path of the federal funds rate. But, again, both the course of the economy and inflation are uncertain. If progress toward our employment and inflation goals is more rapid than expected, it may be appropriate to remove monetary policy accommodation more quickly. However, if progress toward our goals is slower than anticipated, then the Committee may move more slowly in normalizing policy.”

There is essentially the same view in the Testimony of Chair Yellen in delivering the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress on Jul 15, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20150715a.htm). The FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) raised the fed funds rate to ¼ to ½ percent at its meeting on Dec 16, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20151216a.htm).

It is a forecast mandate because of the lags in effect of monetary policy impulses on income and prices (Romer and Romer 2004). The intention is to reduce unemployment close to the “natural rate” (Friedman 1968, Phelps 1968) of around 5 percent and inflation at or below 2.0 percent. If forecasts were reasonably accurate, there would not be policy errors. A commonly analyzed risk of zero interest rates is the occurrence of unintended inflation that could precipitate an increase in interest rates similar to the Himalayan rise of the fed funds rate from 9.91 percent on Jan 10, 1979, at the beginning in Chart VI-10, to 22.36 percent on Jul 22, 1981. There is a less commonly analyzed risk of the development of a risk premium on Treasury securities because of the unsustainable Treasury deficit/debt of the United States (Section I and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/mediocre-cyclical-economic-growth-with.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html

and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html). There is not a fiscal cliff or debt limit issue ahead but rather free fall into a fiscal abyss. The combination of the fiscal abyss with zero interest rates could trigger the risk premium on Treasury debt or Himalayan hike in interest rates.

Chart VI-10, US, Fed Funds Rate, Business Days, Jul 1, 1954 to Oct 11, 2018, Percent per Year

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/datadownload/Choose.aspx?rel=H15