© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017

IA Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy

IB1 Theory

IB2 Policy

IB3 Evidence

IB4 Unwinding Strategy

IC United States Inflation

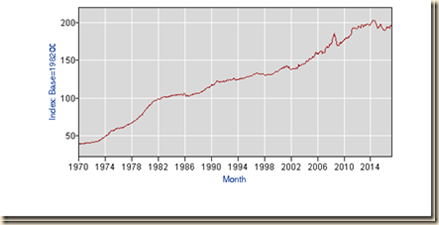

IC Long-term US Inflation

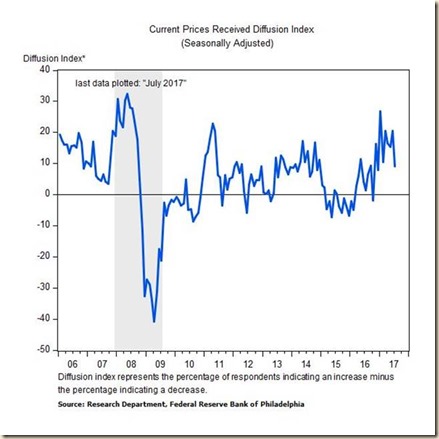

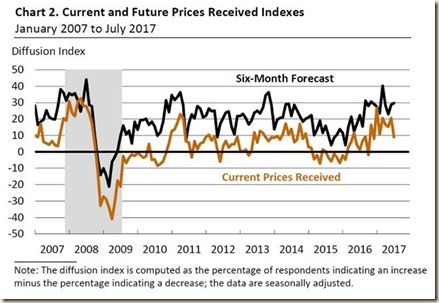

ID Current US Inflation

IE Theory and Reality of Economic History, Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation

II Recovery without Hiring

IA1 Hiring Collapse

IA2 Labor Underutilization

ICA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment

IIB Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates

II IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

I Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels increased by only 4 percent from Jan 2009 to Jan 2012. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job in early 2012 is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer in the American Economic Review (Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 2012May) on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar number of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn, there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (Section I and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_14.html). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled. There are four subsections. IA1 Hiring Collapse provides the data and analysis on the weakness of hiring in the United States economy. IA2 Labor Underutilization provides the measures of labor underutilization of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Statistics on the decline of full-time employment are in IA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment provides the data on high unemployment of ages 16 to 24 years and of ages 45 years or over.

IA1 Hiring Collapse. An important characteristic of the current fractured labor market of the US is the closing of the avenue for exiting unemployment and underemployment normally available through dynamic hiring. Another avenue that is closed is the opportunity for advancement in moving to new jobs that pay better salaries and benefits again because of the collapse of hiring in the United States. Those who are unemployed or underemployed cannot find a new job even accepting lower wages and no benefits. The employed cannot escape declining inflation-adjusted earnings because there is no hiring. The objective of this section is to analyze hiring and labor underutilization in the United States.

Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53 consider an appropriate measure of job stress:

“The right measure of the state of the labor market is the exit rate from unemployment, defined as the number of hires divided by the number unemployed, rather than the unemployment rate itself. What matters to the unemployed is not how many of them there are, but how many of them there are in relation to the number of hires by firms.”

The natural rate of unemployment and the similar NAIRU are quite difficult to estimate in practice (Ibid; see Ball and Mankiw 2002).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) created the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) with the purpose that (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/jltover.htm#purpose):

“These data serve as demand-side indicators of labor shortages at the national level. Prior to JOLTS, there was no economic indicator of the unmet demand for labor with which to assess the presence or extent of labor shortages in the United States. The availability of unfilled jobs—the jobs opening rate—is an important measure of tightness of job markets, parallel to existing measures of unemployment.”

The BLS collects data from about 16,000 US business establishments in nonagricultural industries through the 50 states and DC. The data are released monthly and constitute an important complement to other data provided by the BLS (see also Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 6-7).

There is socio-economic stress in the combination of adverse events and cyclical performance:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources with GDP two trillion dollars below trend (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-rising-yields.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). US GDP grew at the average rate of 3.2 percent per year from 1929 to 2015, with similar performance in whole cycles of contractions and expansions, but only at 1.3 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2016. GDP in IVQ2016 is 14.3 percent lower than what it would have been had it grown at trend of 3.0 percent

- Private fixed investment stagnating at cumulative increase of 11.1 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IQ2017 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-rising-yields.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/dollar-devaluation-mediocre-cyclical.html)

- Twenty two million or 13.0 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/increasing-interest-rates-twenty-four.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-with-exchange-rate.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/turbulence-of-financial-asset.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (Section II and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/flattening-us-treasury-yield-curve.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_14.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-values-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/dollar-revaluation-and-valuations-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rate-uncertainty-and-valuation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/contraction-of-united-states-corporate.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/subdued-foreign-growth-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-volatile_17.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-policy-conundrum-recovery.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/impact-of-monetary-policy-on-exchange.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/dollar-revaluation-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-exchange-rate-struggle-recovery.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/g20-monetary-policy-recovery-without.html)

- Productivity growth fell from 2.1 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2016 and average 2.3 percent per year from 1947 to 2007 to 1.2 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2016, deteriorating future growth and prosperity (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/flattening-us-treasury-yield-curve.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million_14.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/increasing-interest-rates-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-values-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/quite-high-equity-valuations-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/financial-risks-twenty-six-million.html)

- Output of manufacturing in Jun 2017 at 27.0 percent below long-term trend since 1919 and at 19.9 percent below trend since 1986 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/mediocre-cyclical-economic-growth-with.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (Section I and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/interest-rate-policy-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/competitive-currency-conflicts-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins of production across countries in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (Section II and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/fomc-interest-rate-increase-planned.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/dollar-devaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/fomc-increases-interest-rates-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/of-course-economic-outlook-is-highly.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/interest-rate-increase-could-well.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/dollar-revaluation-world-inflation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier) (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/04/twenty-three-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/02/twenty-six-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/12/rising-yields-and-dollar-revaluation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-case-for-increase-in-federal-funds.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/growth-uncertainties-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html)

- 43 million in poverty and 29 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1999 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-imf.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by 22.8 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IQ2017 when it would have grown over 32.6 percent at trend of 3.1 percent per year in real terms from IVQ1945 to IQ2017 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/united-states-commercial-banks-united.html and earlier (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/01/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/of-course-considerable-uncertainty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-fluctuations-of_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/financial-indecision-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/global-financial-risks-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html). Financial assets increased $22.6 trillion while nonfinancial assets increased $4.4 trillion with likely concentration of wealth in those with access to sophisticated financial investments. Real estate assets adjusted for inflation fell 0.8 percent.

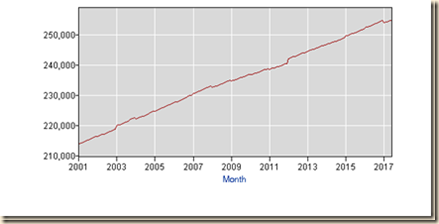

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) revised on Mar 17, 2016 “With the release of January 2016 data on March 17, job openings, hires, and separations data have been revised from December 2000 forward to incorporate annual updates to the Current Employment Statistics employment estimates and the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) seasonal adjustment factors. In addition, all data series are now available on a seasonally adjusted basis. Tables showing the revisions from 2000 through 2015 can be found using this link: http://www.bls.gov/jlt/revisiontables.htm.” (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) revised on Mar 16, 2017: “With the release of January 2017 data on March 16, job openings, hires, and separations data have been revised to incorporate annual updates to the Current Employment Statistics employment estimates and the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) seasonal adjustment factors” (https://www.bls.gov/jlt/revisiontables.htm) (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/). Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 63.491 million in 2006 to 62.719 million in 2016 or by 0.772 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 59.206 million in 2006 to 58.385 million in 2016 or by 0.821 million, as shown in Table I-1. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) has fallen from 47.1 in 2005 to 43.5 in 2016 and in the private sector (RHP) from 52.8 in 2005 to 47.8 in 2016. Hiring has not recovered as in previous cyclical expansions because of the low rate of economic growth in the current cyclical expansion. The civilian noninstitutional population or those in condition to work increased from 228.815 million in 2006 to 253.538 million in 2016 or by 24.723 million. Hiring has not recovered prerecession levels while needs of hiring multiplied because of growth of population by more than 24 million. Private hiring of 59.206 million in 2006 was equivalent to 25.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 228.815, or those in condition of working, falling to 58.385 million in 2016 or 23.0 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 253.538 million in 2016. The percentage of hiring in civilian noninstitutional population of 25.9 percent in 2006 would correspond to 65.666 million of hiring in 2016 (0.259x253.538), which would be 7.281 million higher than actual 58.385 million in 2016. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.1 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 31 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IQ2017. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the third estimate of GDP for IQ2017 (https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2017/pdf/gdp1q17_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by dividing GDP of $14,745.9 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,355.6 billion in IIQ2009 {[($14,745.9/$14,355.6) -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-rising-yields.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1989, 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1989. 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1990, 4.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1990, 4.3 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1990 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html). The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates a contraction of the US from IQ1990 (Jul) to IQ1991 (Mar) (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). The expansion lasted until another contraction beginning in IQ2001 (Mar). US GDP contracted 1.3 percent from the pre-recession peak of $8983.9 billion of chained 2009 dollars in IIIQ1990 to the trough of $8865.6 billion in IQ1991 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IQ2017 would have accumulated to 31.4 percent. GDP in IQ2017 would be $19,699.2 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2826.4 billion than actual $16,872.8 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 21.9 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment/underemployment of 13.0 percent of the effective labor force (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html). US GDP in IQ2017 is 14.3 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,872.8 billion in IQ2017 or 12.5 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.3 percent. Professor John H. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. Cochrane (2016May02) measures GDP growth in the US at average 3.5 percent per year from 1950 to 2000 and only at 1.76 percent per year from 2000 to 2015 with only at 2.0 percent annual equivalent in the current expansion. Cochrane (2016May02) proposes drastic changes in regulation and legal obstacles to private economic activity. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Jun 1919 to Jun 2017. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.2393 in Dec 2007 to 144.6580 in Jun 2017. The actual index NSA in Jun 2017 is 105.6126, which is 27.0 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.1 percent between Dec 1986 and Jun 2017. Using trend growth of 2.1 percent per year, the index would increase to 131.8650 in Jun 2017. The output of manufacturing at 105.6126 in Jun 2017 is 19.9 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table I-1, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in Thousands and Percentage of Total Employment

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 | 62,727 | 47.5 | 58,616 | 52.8 |

| 2002 | 58,416 | 44.7 | 54,592 | 50.0 |

| 2003 | 56,919 | 43.7 | 53,529 | 49.2 |

| 2004 | 60,236 | 45.7 | 56,567 | 51.3 |

| 2005 | 63,089 | 47.1 | 59,298 | 52.8 |

| 2006 | 63,491 | 46.5 | 59,206 | 51.7 |

| 2007 | 62,239 | 45.1 | 57,816 | 49.9 |

| 2008 | 54,764 | 39.9 | 51,260 | 44.7 |

| 2009 | 46,190 | 35.2 | 42,882 | 39.4 |

| 2010 | 48,659 | 37.3 | 44,831 | 41.6 |

| 2011 | 50,253 | 38.1 | 47,166 | 42.9 |

| 2012 | 52,332 | 39.0 | 48,898 | 43.6 |

| 2013 | 54,320 | 39.8 | 50,882 | 44.4 |

| 2014 | 58,657 | 42.2 | 55,001 | 47.0 |

| 2015 | 62,050 | 43.7 | 57,909 | 48.3 |

| 2016 | 62,719 | 43.5 | 58,385 | 47.8 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

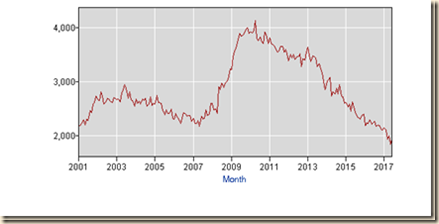

Chart I-1 shows the annual level of total nonfarm hiring (HNF) that collapsed during the global recession after 2007 in contrast with milder decline in the shallow recession of 2001. Nonfarm hiring has not recovered, remaining at a depressed level. The civilian noninstitutional population or those in condition to work increased from 228.815 million in 2006 to 253.538 million in 2016 or by 24.723 million. Hiring has not recovered precession levels while needs of hiring multiplied because of growth of population by more than 24 million.

Chart I-1, US, Level Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual, 2001-2016

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

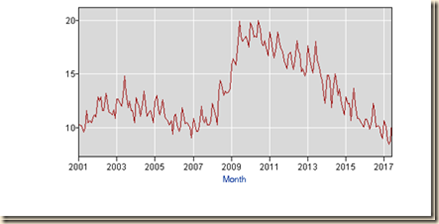

Chart I-2 shows the ratio or rate of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) that also fell much more in the recession of 2007 to 2009 than in the shallow recession of 2001. Recovery is weak in the current environment of cyclical slow growth.

Chart I-2, US, Rate Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual, 2001-2016

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Yearly percentage changes of total nonfarm hiring (HNF) are provided in Table I-2. There were much milder declines in 2002 of 6.9 percent and 2.6 percent in 2003 followed by strong rebounds of 5.8 percent in 2004 and 4.7 percent in 2005. In contrast, the contractions of nonfarm hiring in the recession after 2007 were much sharper in percentage points: 2.0 in 2007, 12.0 in 2008 and 15.7 percent in 2009. On a yearly basis, nonfarm hiring grew 5.3 percent in 2010 relative to 2009, 3.3 percent in 2011, 4.1 percent in 2012 and 3.8 percent in 2013. Nonfarm hiring grew 8.0 percent in 2014 and increased 5.8 percent in 2015. Nonfarm hiring grew 1.1 percent in 2016. The relatively large length of 27 quarters of the current expansion reduces the likelihood of significant recovery of hiring levels in the United States because lower rates of growth and hiring in the final phase of expansions.

Table I-2, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual Percentage Change, 2002-2016

| Year | Annual ∆% |

| 2002 | -6.9 |

| 2003 | -2.6 |

| 2004 | 5.8 |

| 2005 | 4.7 |

| 2006 | 0.6 |

| 2007 | -2.0 |

| 2008 | -12.0 |

| 2009 | -15.7 |

| 2010 | 5.3 |

| 2011 | 3.3 |

| 2012 | 4.1 |

| 2013 | 3.8 |

| 2014 | 8.0 |

| 2015 | 5.8 |

| 2016 | 1.1 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Total private hiring (HP) 12-month percentage changes of annual data are in Chart I-3. There has been sharp contraction of total private hiring in the US and only milder recovery from 2010 to 2016.

Chart I-5, US, Total Private Hiring, Annual, 2001-2016

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Total private hiring (HP) annual data are in Chart I-5. There has been sharp contraction of total private hiring in the US and only milder recovery from 2010 to 2016.

Chart I-5A, US, Rate Total Private Hiring, Annual, 2001-2016

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Total nonfarm hiring (HNF), total private hiring (HP) and their respective rates are in Table I-3 for the month of May in the years from 2001 to 2017. Hiring numbers are in thousands. There is recovery in HNF from 4187 thousand (or 4.2 million) in May 2009 to 4815 thousand in May 2010, 4617 thousand in May 2011, 4968 thousand in May 2012, 5128 thousand in May 2013, 5400 thousand in May 2014, 5732 thousand in May 2015, 5692 thousand in May 2016, and 6032 in May 2017 for cumulative gain of 44.1 percent at average rate of 4.7 percent per year. HP rose from 3908 thousand in May 2009 to 4060 thousand in May 2010, 4347 thousand in May 2011, 4665 thousand in May 2012, 4826 thousand in May 2013, 5068 thousand in May 2014, 5367 in May 2015, 5295 thousand in May 2016, and 5680 thousand in May 2017 for cumulative gain of 45.3 percent at the average yearly rate of 4.8 percent. HNF has increased from 5931 thousand in May 2006 to 6032 thousand in May 2017 or by 1.7 percent. HP has increased from 5546 thousand in May 2006 to 5680 thousand in May 2017 or by 2.4 percent. The civilian noninstitutional population of the US, or those in condition of working, rose from 228.428 million in May 2006 to 254.767 million in May 2017, by 26.339 million or 11.5 percent. There is often ignored ugly fact that hiring increased by around 2.4 percent while population available for working increased around 11.5 percent. Private hiring of 59.206 million in 2006 was equivalent to 25.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 228.815, or those in condition of working, falling to 58.385 million in 2016 or 23.0 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 253.538 million in 2016. The percentage of hiring in civilian noninstitutional population of 25.9 percent in 2006 would correspond to 65.666 million of hiring in 2016 (0.259x253.538), which would be 7.281 million higher than actual 58.385 million in 2016. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. Cyclical slow growth over the entire business cycle from IVQ2007 to the present in comparison with earlier cycles and long-term trend (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-rising-yields.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html) explains the fact that there are many million fewer hires in the US than before the global recession. The labor market continues to be fractured, failing to provide an opportunity to exit from unemployment/underemployment or to find an opportunity for advancement away from declining inflation-adjusted earnings.

Table I-3, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in

Thousands and in Percentage of Total Employment Not Seasonally Adjusted

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 May | 5841 | 4.4 | 5462 | 4.9 |

| 2002 May | 5334 | 4.1 | 4978 | 4.6 |

| 2003 May | 4999 | 3.8 | 4710 | 4.3 |

| 2004 May | 5356 | 4.0 | 5068 | 4.6 |

| 2005 May | 5729 | 4.3 | 5406 | 4.8 |

| 2006 May | 5931 | 4.3 | 5546 | 4.8 |

| 2007 May | 5758 | 4.2 | 5353 | 4.6 |

| 2008 May | 5058 | 3.7 | 4730 | 4.1 |

| 2009 May | 4187 | 3.2 | 3908 | 3.6 |

| 2010 May | 4815 | 3.7 | 4060 | 3.8 |

| 2011 May | 4617 | 3.5 | 4347 | 4.0 |

| 2012 May | 4968 | 3.7 | 4665 | 4.2 |

| 2013 May | 5128 | 3.7 | 4826 | 4.2 |

| 2014 May | 5400 | 3.9 | 5068 | 4.3 |

| 2015 May | 5732 | 4.0 | 5367 | 4.5 |

| 2016 May | 5692 | 3.9 | 5295 | 4.3 |

| 2017 May | 6032 | 4.1 | 5680 | 4.6 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

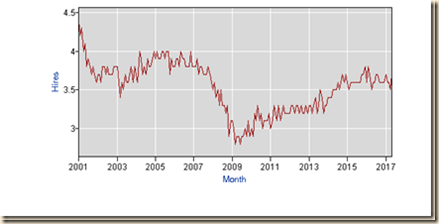

Chart I-6 provides total nonfarm hiring monthly from 2001 to 2017. Nonfarm hiring rebounded in early 2010 but then fell and stabilized at a lower level than the early peak not-seasonally adjusted (NSA) of 4815 in May 2010 until it surpassed it with 5006 in Jun 2011 but declined to 3097 in Dec 2012. Nonfarm hiring fell to 2997 in Dec 2011 from 3814 in Nov 2011 and to revised 3627 in Feb 2012, increasing to 4182 in Mar 2012, 3097 in Dec 2012 and 4277 in Jan 2013 and declining to 3692 in Feb 2013. Nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted increased to 4239 in Nov 2013 and 3233 in Dec 2013. Nonfarm hires reached 3729 in Dec 2014, 4057 in Dec 2015 and 3905 in Dec 2016. Nonfarm hires reached 6032 in May 2017. Chart I-6 provides seasonally adjusted (SA) monthly data. The number of seasonally-adjusted hires in Oct 2011 was 4239 thousand, increasing to revised 4419 thousand in Feb 2012, or 4.2 percent, moving to 4360 in Dec 2012 for cumulative increase of 3.0 percent from 4234 in Dec 2011 and 4500 in Dec 2013 for increase of 3.2 percent relative to 4360 in Dec 2012. The number of hires not seasonally adjusted was 5006 in Jun 2011, falling to 2997 in Dec 2011 but increasing to 4140 in Jan 2012 and declining to 3097 in Dec 2012. The number of nonfarm hiring not seasonally adjusted fell by 40.1 percent from 5006 in Jun 2011 to 2997 in Dec 2011 and fell 39.9 percent from 5151 in Jun 2012 to 3097 in Dec 2012 in a yearly-repeated seasonal pattern. The number of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 5102 in Jun 2013 to 3233 in Dec 2013, or decline of 36.6 percent, showing strong seasonality. The number of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 5520 in Jun 2014 to 3729 in Dec 2014 or 32.4 percent. The level of nonfarm hires fell from 5885 in Jun 2015 to 4057 in Dec 2015 or 31.1 percent. The level of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 5922 in Jun 2016 to 3905 in Dec 2016 or 34.1 percent.

Chart I-6, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), 2001-2017 Month SA

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Similar behavior occurs in the rate of nonfarm hiring in Chart I-7. Recovery in early 2010 was followed by decline and stabilization at a lower level but with stability in monthly SA estimates of 3.2 in Aug 2011 to 3.2 in Jan 2012, increasing to 3.3 in May 2012 and stabilizing to 3.3 in Jun 2012. The rate stabilized at 3.2 in Jul 2012, increasing to 3.3 in Aug 2012 but falling to 3.2 in Dec 2012 and 3.3 in Dec 2013. The rate not seasonally adjusted fell from 3.8 in Jun 2011 to 2.2 in Dec 2011, climbing to 3.8 in Jun 2012 but falling to 2.3 in Dec 2012. The rate of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Jun 2013 to 2.3 in Dec 2013. The NSA rate of nonfarm hiring fell from 3.9 in Jun 2014 to 2.6 in Dec 2014. The NSA rate fell from 4.1 in Jun 2015 to 2.8 in Dec 2015. The NSA rate fell from 4.1 in Jun 2016 to 2.7 in Dec 2016. Rates of nonfarm hiring NSA were in the range of 2.7 (Dec) to 4.4 (Jun) in 2006. The rate of nonfarm hiring SA stood at 3.7 in May 2017 and at 4.1 NSA.

Chart I-7, US, Rate Total Nonfarm Hiring, Month SA 2001-2017

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

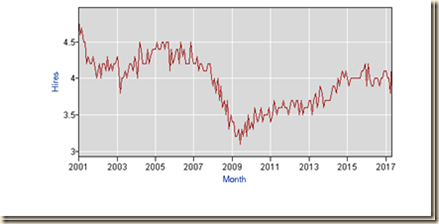

There is only milder improvement in total private hiring shown in Chart I-8. Hiring private (HP) rose in 2010 with stability and renewed increase in 2011 followed by almost stationary series in 2012. The number of private hiring seasonally adjusted fell from 4043 thousand in Sep 2011 to 3933 in Dec 2011 or by 2.7 percent, decreasing to 4014 in Jan 2012 or decline by 0.7 percent relative to the level in Sep 2011. Private hiring fell to 3959 in Sep 2012 or lower by 2.1 percent relative to Sep 2011, moving to 4063 in Dec 2012 for increase of 1.2 percent relative to 4014 in Jan 2012. The number of private hiring not seasonally adjusted fell from 4626 in Jun 2011 to 2817 in Dec 2011 or by 39.1 percent, reaching 3885 in Jan 2012 or decline of 16.0 percent relative to Jun 2011 and moving to 2918 in Dec 2012 or 38.5 percent lower relative to 4745 in Jun 2012. Hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 4743 in Jun 2013 to 3068 in Dec 2013. The level of private hiring NSA fell from 5101 in Jun 2014 to 3530 in Dec 2014 or 30.8 percent. The level of private hiring fell from 5452 in Jun 2015 to 3828 in Dec 2015 or 29.8 percent. The level of private hiring not seasonally adjusted fell from 5456 in Jun 2016 to 3711 in Dec 2016 or 32.0 percent. Companies reduce hiring in the latter part of the year that explains the high seasonality in year-end employment data. For example, NSA private hiring fell from 5614 in Jun 2006 to 3579 in Dec 2006 or by 36.2 percent. Private hiring NSA data are useful in showing the huge declines from the period before the global recession. Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 63.491 million in 2006 to 62.719 million in 2016 or by 0.772 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 59.206 million in 2006 to 58.385 million in 2016 or by 0.821 million, as shown in Table I-1. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) has fallen from 47.1 in 2005 to 43.5 in 2016 and in the private sector (RHP) from 52.8 in 2005 to 47.8 in 2016. Hiring has not recovered as in previous cyclical expansions because of the low rate of economic growth in the current cyclical expansion. The civilian noninstitutional population or those in condition to work increased from 228.815 million in 2006 to 253.538 million in 2016 or by 24.723 million. Hiring has not recovered prerecession levels while needs of hiring multiplied because of growth of population by more than 24 million. Private hiring of 59.206 million in 2006 was equivalent to 25.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 228.815, or those in condition of working, falling to 58.385 million in 2016 or 23.0 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 253.538 million in 2016. The percentage of hiring in civilian noninstitutional population of 25.9 percent in 2006 would correspond to 65.666 million of hiring in 2016 (0.259x253.538), which would be 7.281 million higher than actual 58.385 million in 2016.

Chart I-8, US, Total Private Hiring Month SA 2001-2017

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

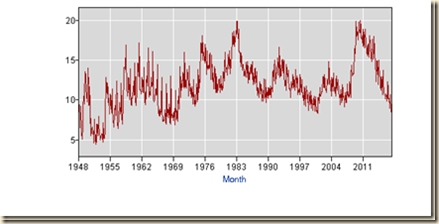

Chart I-9 shows similar behavior in the rate of private hiring. The rate in 2011 in monthly SA data did not rise significantly above the peak in 2010. The rate seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Sep 2011 to 3.5 in Dec 2011 and reached 3.6 in Dec 2012 and 3.7 in Dec 2013. The rate not seasonally adjusted (NSA) fell from 3.7 in Sep 2011 to 2.5 in Dec 2011, increasing to 3.8 in Oct 2012 but falling to 2.6 in Dec 2012 and 3.4 in Mar 2013. The NSA rate of private hiring fell from 4.8 in Jul 2006 to 3.4 in Aug 2009 but recovery was insufficient to only 3.9 in Aug 2012, 2.6 in Dec 2012 and 2.6 in Dec 2013. The NSA rate increased to 3.1 in Dec 2015 and 3.0 in Dec

2016. The rate NSA reached 4.6 in May 2017.

Chart I-9, US, Rate Total Private Hiring Month SA 2001-2017

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

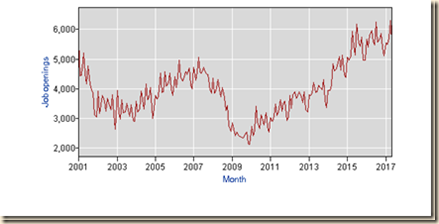

The JOLTS report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics also provides total nonfarm job openings (TNF JOB), TNF JOB rate and TNF LD (layoffs and discharges) shown in Table I-4 for the month of Apr from 2001 to 2017. The final column provides annual TNF LD for the years from 2001 to 2016. Nonfarm job openings (TNF JOB) increased from a peak of 4564 in May 2007 to 5665 in May 2017 or by 24.1 percent while the rate increased from 3.2 to 3.7. This was mediocre performance because the civilian noninstitutional population of the US, or those in condition of working rose from 231.480 million in May 2007 to 254.767 million in May 2017, by 23.287 million or 10.1 percent. Nonfarm layoffs and discharges (TNF LD) rose from 1648 in Apr 2006 to 2351 in Apr 2009 or by 42.7 percent. The annual data show layoffs and discharges rising from 20.9 million in 2006 to 26.6 million in 2009 or by 27.3 percent. Business pruned payroll jobs to survive the global recession but there has not been hiring because of the low rate of GDP growth. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions.

Table I-4, US, Total Nonfarm Job Openings and Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Thousands NSA

| TNF JOB | TNF JOB | TNF LD | TNF LD | |

| May 2001 | 4515 | 3.3 | 1637 | 24271 |

| May 2002 | 3575 | 2.8 | 1609 | 22719 |

| May 2003 | 3205 | 2.4 | 1607 | 23420 |

| May 2004 | 3643 | 2.7 | 1517 | 22584 |

| May 2005 | 3879 | 2.8 | 1577 | 22151 |

| May 2006 | 4388 | 3.1 | 1627 | 20856 |

| May 2007 | 4564 | 3.2 | 1523 | 21997 |

| May 2008 | 3974 | 2.8 | 1623 | 23969 |

| May 2009 | 2427 | 1.8 | 1905 | 26557 |

| May 2010 | 2893 | 2.2 | 1584 | 21703 |

| May 2011 | 3110 | 2.3 | 1583 | 20756 |

| May 2012 | 3692 | 2.7 | 1727 | 20942 |

| May 2013 | 3873 | 2.8 | 1631 | 19888 |

| May 2014 | 4607 | 3.2 | 1567 | 20398 |

| May 2015 | 5428 | 3.7 | 1599 | 20954 |

| May 2016 | 5591 | 3.7 | 1664 | 19911 |

| May 2017 | 5665 | 3.7 | 1594 |

Notes: TNF JOB: Total Nonfarm Job Openings; LD: Layoffs and Discharges

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

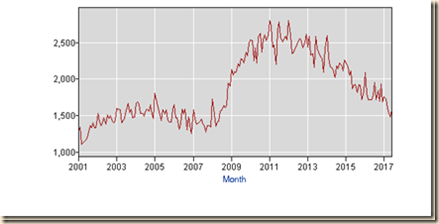

Chart I-10 shows monthly job openings rising from the trough in 2009 to a high in the beginning of 2010. Job openings then stabilized into 2011 but have surpassed the peak of 3220 seasonally adjusted in Apr 2010 with 3570 seasonally adjusted in Dec 2012, which is higher by 10.9 percent relative to Apr 2010 but higher by 1.4 percent relative to 3521 in Nov 2012 and lower by 6.8 percent than 3831 in Mar 2012. Nonfarm job openings increased from 3570 in Dec 2012 to 3742 in Dec 2013 or by 4.8 percent and to 4795 in Dec 2014 or 28.1 percent relative to 2013. The high of job openings not seasonally adjusted was 3408 in Apr 2010 that was surpassed by 3647 in Jul 2011, increasing to 3906 in Oct 2012 but declining to 3213 in Dec 2012 and increasing to 3371 in Dec 2013. The level of job opening NSA increased to 4961 in Dec 2015. The level of job opening NSA increased to 5116 in Dec 2016, reaching 5665 in May 2017. The level of job openings not seasonally adjusted fell to 3213 in Dec 2012 or by 17.5 percent relative to 3893 in Apr 2012. There is here again the strong seasonality of year-end labor data. Job openings fell from 4209 in Apr 2013 to 3371 in Dec 2013 and from 4844 in Apr 2014 to 4398 in Dec 2014, showing strong seasonal effects. The level of nonfarm job openings decreased from 5933 in Apr 2015 to 4961 in Dec 2015 or by 16.4 percent. The level of nonfarm job openings NSA fell from 5951 in Apr 2016 to 5116 in Dec 2016 or 14.0 percent. Nonfarm job openings (TNF JOB) increased from a peak of 4564 in May 2007 to 5665 in May 2017 or by 24.1 percent while the rate increased from 3.2 to 3.7. This was mediocre performance because the civilian noninstitutional population of the US, or those in condition of working rose from 231.480 million in May 2007 to 254.767 million in May 2017, by 23.287 million or 10.1 percent. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.1 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 31 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IQ2017. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the third estimate of GDP for IQ2017 (https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2017/pdf/gdp1q17_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by dividing GDP of $14,745.9 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,355.6 billion in IIQ2009 {[($14,745.9/$14,355.6) -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/dollar-devaluation-and-rising-yields.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1989, 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1989. 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1990, 4.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1990, 4.3 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1990 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/05/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html). The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates a contraction of the US from IQ1990 (Jul) to IQ1991 (Mar) (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). The expansion lasted until another contraction beginning in IQ2001 (Mar). US GDP contracted 1.3 percent from the pre-recession peak of $8983.9 billion of chained 2009 dollars in IIIQ1990 to the trough of $8865.6 billion in IQ1991 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IQ2017 would have accumulated to 31.4 percent. GDP in IQ2017 would be $19,699.2 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2826.4 billion than actual $16,872.8 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 21.9 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment/underemployment of 13.0 percent of the effective labor force (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/07/rising-yields-twenty-two-million.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2017/06/twenty-two-million-unemployed-or.html). US GDP in IQ2017 is 14.3 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,872.8 billion in IQ2017 or 12.5 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.3 percent. Professor John H. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. Cochrane (2016May02) measures GDP growth in the US at average 3.5 percent per year from 1950 to 2000 and only at 1.76 percent per year from 2000 to 2015 with only at 2.0 percent annual equivalent in the current expansion. Cochrane (2016May02) proposes drastic changes in regulation and legal obstacles to private economic activity. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Jun 1919 to Jun 2017. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.2393 in Dec 2007 to 144.6580 in Jun 2017. The actual index NSA in Jun 2017 is 105.6126, which is 27.0 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.1 percent between Dec 1986 and Jun 2017. Using trend growth of 2.1 percent per year, the index would increase to 131.8650 in Jun 2017. The output of manufacturing at 105.6126 in Jun 2017 is 19.9 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Chart I-10, US Job Openings, Thousands NSA, 2001-2017

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

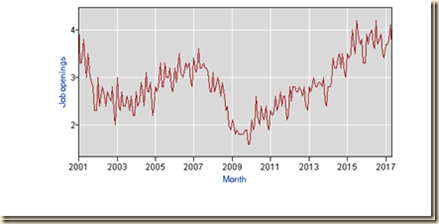

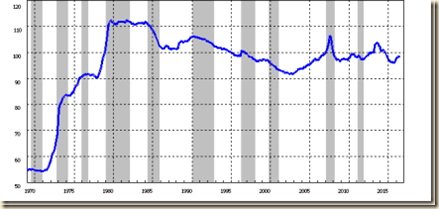

The rate of job openings in Chart I-11 shows similar behavior. The rate seasonally adjusted increased from 2.2 in Jan 2011 to 2.5 in Dec 2011, 2.6 in Dec 2012, 2.7 in Dec 2013 and 3.3 in Dec 2014. The rate seasonally adjusted stood at 3.6 in Dec 2015 and 3.7 in Dec 2016. The rate seasonally adjusted reached 3.7 in May 2017. The rate not seasonally adjusted rose from the high of 2.6 in Apr 2010 to 3.0 in Apr 2013, easing to 2.4 in Dec 2013. The rate of job openings NSA fell from 3.3 in Jul 2007 to 1.6 in Nov-Dec 2009, recovering to 3.3 in Dec 2015. The rate of job opening NSA stood at 3.4 in Dec 2016, reaching 3.7 in May 2017.

Chart I-11, US, Rate of Job Openings, NSA, 2001-2017

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

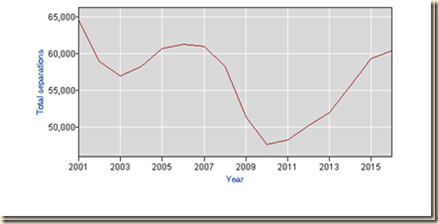

Total separations are in Chart I-12. Separations are lower in 2012-17 than before the global recession but hiring has not recovered.

Chart I-12, US, Total Nonfarm Separations, Month Thousands SA, 2001-2017

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-13 provides annual total separations. Separations fell sharply during the global recession but hiring has not recovered relative to population growth.

Chart I-13, US, Total Separations, Annual, Thousands, 2001-2016

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-5 provides total nonfarm total separations from 2001 to 2016. Separations fell from 61.3 million in 2006 to 47.6 million in 2010 or by 13.6 million and 48.2 million in 2011 or by 13.1 million. Total separations increased from 48.2 million in 2011 to 51.9 million in 2013 or by 3.7 million and to 55.6 million in 2014 or by 7.4 million relative to 2011. Total separations increased to 59.3 million in 2015 or by 11.1 million relative to 2011. Total separations increased to 60.419 million in 2016 or 12.2 million relative to 2011.

Table I-5, US, Total Nonfarm Total Separations, Thousands, 2001-2016

| Year | Annual Thousands |

| 2001 | 64560 |

| 2002 | 58942 |

| 2003 | 56961 |

| 2004 | 58224 |

| 2005 | 60633 |

| 2006 | 61284 |

| 2007 | 60984 |

| 2008 | 58209 |

| 2009 | 51358 |

| 2010 | 47649 |

| 2011 | 48214 |

| 2012 | 50131 |

| 2013 | 51932 |

| 2014 | 55587 |

| 2015 | 59275 |

| 2016 | 60419 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

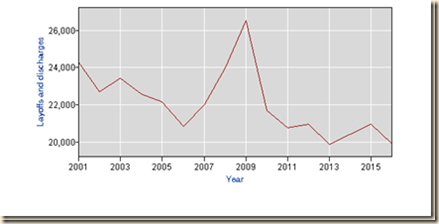

Monthly data of layoffs and discharges reach a peak in early 2009, as shown in Chart I-14. Layoffs and discharges dropped sharply with the recovery of the economy in 2010 and 2011 once employers reduced their job count to what was required for cost reductions and loss of business. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth. Growth rates have been unusually low in the expansion of the current economic cycle.

Chart I-14, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Monthly Thousands SA, 2001-2017

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Layoffs and discharges in Chart I-15 rose sharply to a peak in 2009. There was pronounced drop into 2010 and 2011 with mild increase into 2012 and renewed decline into 2013. There is mild increase into 2014-2015 followed by decline in 2016.

Chart I-15, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Annual, 2001-2016

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Annual layoff and discharges are in Table I-6. Layoffs and discharges increased sharply from 20.856 million in 2006 to 26.557 million in 2009 or 27.3 percent. Layoff and discharges fell to 19.888 million in 2013 or 25.1 percent relative to 2009 and increased to 20.398 million in 2014 or 2.6 percent relative to 2013. Layoffs and discharges increased to 20.954 million in 2015 or 2.7 percent relative to 2014. Layoffs and discharges fell to 19.911 in 2016 or 5.0 percent relative to 2015.

Table I-6, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Thousands, 2001-2016

| Year | Annual Thousands |

| 2001 | 24271 |

| 2002 | 22719 |

| 2003 | 23420 |

| 2004 | 22584 |

| 2005 | 22151 |

| 2006 | 20856 |

| 2007 | 21997 |

| 2008 | 23969 |