Financial Instability, Rules, Discretionary Authorities and Slow Productivity Growth, Thirty Million Unemployed or Underemployed, Stagnating Real Wages, United States International Trade, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Executive Summary

I Thirty Million Unemployed or Underemployed

IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation

IA2 Number of People in Job Stress

IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment

IA4 Job Creation

IB Stagnating Real Wages

II United States International Trade

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

V World Economic Slowdown. Table V-1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx) to show GDP in dollars in 2012 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2013 to 2016. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has lowered its forecast of the world economy to 2.9 percent in 2013 but accelerating to 3.6 percent in 2014, 4.0 percent in 2015 and 4.1 percent in 2016. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $34,560 billion of world output of $72,216 billion, or 47.9 percent, but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 2.1 percent on average from 2013 to 2016 in contrast with 3.6 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would grow 15.4 percent in the four years from 2013 to 2016, the G7 as a whole would grow 8.6 percent. The difference in dollars of 2012 is rather high: growing by 15.4 percent would add $11.1 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly, two times the output of the economy of Japan of $5,960 billion but growing by 8.6 percent would add $6.2 trillion of output to the world, or about the output of Japan in 2012. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2012 of $27,221 billion, or 37.7 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 21.9 percent or at the average yearly rate of 5.1 percent, contributing $6.0 trillion from 2013 to 2016 or the equivalent of somewhat less than the GDP of $8,221 billion of China in 2012. The final four countries in Table V-1 often referred as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output in 2012 adds to $14,346 billion, or 19.9 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 41.5 percent of the combined output of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table V-1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2012 | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | |

| World | 72,216 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| G7 | 34,560 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Canada | 1,821 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| France | 2,614 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| DE | 3,430 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Japan | 5,960 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| UK | 2,477 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| US | 16,245 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Euro Area | 12,199 | -0.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| DE | 3,430 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| France | 2,614 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| POT | 212 | -1.8 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Ireland | 211 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Greece | 249 | -4.2 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Spain | 1,324 | -1.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| EMDE | 27,221 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| Brazil | 2,253 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Russia | 2,030 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| India | 1,842 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| China | 8,221 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); POT: Portugal

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx). Table V-2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2012 to 2016 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates for 2012 in Table V-2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 15.7 percent for Portugal (POT), 14.7 percent for Ireland, 24.2 percent for Greece, 25.0 percent for Spain and 10.6 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 7.4 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table V-2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2012 | % Labor Force 2013 | % Labor Force 2014 | % Labor Force 2015 | % Labor Force 2016 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| Canada | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 |

| France | 10.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.5 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 11.2 |

| Japan | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| UK | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| US | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 |

| Euro Area | 11.4 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 11.5 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| France | 10.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.5 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 11.2 |

| POT | 15.7 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 16.8 |

| Ireland | 14.7 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 12.4 |

| Greece | 24.2 | 27.0 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 21.0 |

| Spain | 25.0 | 26.9 | 26.7 | 26.5 | 26.2 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 5.5 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Russia | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| China | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

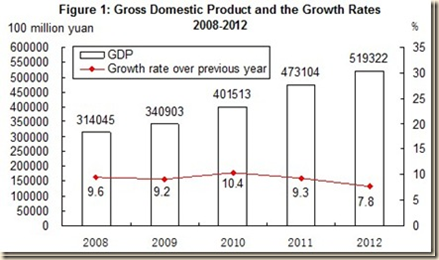

Table V-3 provides the latest available estimates of GDP for the regions and countries followed in this blog from IQ2012 to IIQ2013 available now for all countries. There are preliminary estimates for all countries for IIIQ2013. Growth is weak throughout most of the world. Japan’s GDP increased 0.9 percent in IQ2012 and 3.5 percent relative to a year earlier but part of the jump could be the low level a year earlier because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan is experiencing difficulties with the overvalued yen because of worldwide capital flight originating in zero interest rates with risk aversion in an environment of softer growth of world trade. Japan’s GDP fell 0.5 percent in IIQ2012 at the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of minus 2.0 percent, which is much lower than 3.5 percent in IQ2012. Growth of 3.2 percent in IIQ2012 in Japan relative to IIQ2011 has effects of the low level of output because of Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan’s GDP contracted 0.8 percent in IIIQ2012 at the SAAR of minus 3.2 percent and decreased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP grew 0.1 percent in IVQ2012 at the SAAR of 0.6 percent and decreased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan grew 1.1 percent in IQ2013 at the SAAR of 4.5 percent and 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP increased 0.9 percent in IIQ2013 at the SAAR of 3.6 percent and increased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 at the SAAR of 1.1 percent and increased 2.4 pecent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.1 percent in IIQ2012, which annualizes to 8.7 percent and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.0 percent in IIIQ2012, which annualizes at 8.2 percent and 7.4 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 7.9 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, China grew at 1.5 percent, which annualizes at 6.1 percent and 7.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, China grew at 1.8 percent, which annualizes at 7.4 percent and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.2 percent in IIIQ2013, which annualizes at 9.1 percent and 7.8 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 1.8 percent in IVQ2013, which annualized to 7.4 percent and 7.7 percent relative to a year earlier. There is decennial change in leadership in China (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/index.htm). Growth rates of GDP of China in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier have been declining from 2011 to 2013. GDP fell 0.1 percent in the euro area in IQ2012 and decreased 0.2 in IQ2012 relative to a year earlier. Euro area GDP contracted 0.3 percent IIQ2012 and fell 0.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.2 percent and declined 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.5 percent relative to the prior quarter and fell 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, the GDP of the euro area fell 0.2 percent and decreased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2013 and fell 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, euro area GDP increased 0.1 percent and fell 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.7 percent in IQ2012 and 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2012, Germany’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent and increased 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier but 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier when adjusted for calendar (CA) effects. In IIIQ2012, Germany’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP contracted 0.5 percent in IVQ2012 and increased 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.0 percent and fell 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.7 percent and 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 and 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Growth of US GDP in IQ2012 was 0.9 percent, at SAAR of 3.7 percent and higher by 3.3 percent relative to IQ2011. US GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2012, 1.2 percent at SAAR and 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, US GDP grew 0.7 percent, 2.8 percent at SAAR and 3.1 percent relative to IIIQ2011. In IVQ2012, US GDP grew 0.0 percent, 0.1 percent at SAAR and 2.0 percent relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, US GDP grew at 1.1 percent SAAR, 0.3 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.3 percent relative to the same quarter in 2013. In IIQ2013, US GDP grew at 2.5 percent in SAAR, 0.6 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.6 percent relative to IIQ2012. US GDP grew at 4.1 percent in SAAR in IIIQ2013, 1.0 percent relative to the prior quarter and 2.0 percent relative to the same quarter a year earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html) with weak hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html). In IVQ2013, US GDP grew 0.8 percent at 3.2 percent SAAR and 2.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2012, UK GDP changed 0.0 percent, increasing 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP fell 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIIQ2012 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP fell 0.1 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IIIQ2012 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.5 percent in IQ2013 and 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIQ2013 and 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, UK GDP increased 0.8 percent and 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.7 percent in IVQ2013 and 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy has experienced decline of GDP in nine consecutive quarters from IIIQ2011 to IIIQ2013. Italy’s GDP fell 1.1 percent in IQ2012 and declined 1.8 percent relative to IQ2011. Italy’s GDP fell 0.6 percent in IIQ2012 and declined 2.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, Italy’s GDP fell 0.5 percent and declined 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy contracted 0.9 percent in IVQ2012 and fell 3.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, Italy’s GDP contracted 0.6 percent and fell 2.5 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP fell 0.3 percent in IIQ2013 and 2.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy changed 0.0 percent in IIIQ2013 and declined 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IQ2012 and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP decreased 0.3 percent in IIQ2012 and increased 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, France’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP fell 0.2 percent in IVQ2012 and declined 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, France GDP fell 0.1 percent and declined 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France increased 0.6 percent in IIQ2013 and 0.5 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP contracted 0.1 percent in IIIQ2013 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier.

Table V-3, Percentage Changes of GDP Quarter on Prior Quarter and on Same Quarter Year Earlier, ∆%

| IQ2012/IVQ2011 | IQ2012/IQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.5 | 3.1 |

| China | 1.4 | 8.1 |

| Euro Area | -0.1 | -0.2 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| France | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Italy | -1.1 | -1.8 |

| United Kingdom | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| IIQ2012/IQ2012 | IIQ2012/IIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.3 SAAR: 1.2 | 2.8 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.5 | 3.2 |

| China | 2.1 | 7.6 |

| Euro Area | -0.3 | -0.5 |

| Germany | -0.1 | 0.6 1.1 CA |

| France | -0.3 | 0.1 |

| Italy | -0.6 | -2.6 |

| United Kingdom | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| IIIQ2012/ IIQ2012 | IIIQ2012/ IIIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Japan | QOQ: –0.8 | -0.2 |

| China | 2.0 | 7.4 |

| Euro Area | -0.2 | -0.7 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Italy | -0.5 | -2.8 |

| United Kingdom | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| IVQ2012/IIIQ2012 | IVQ2012/IVQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.1 SAAR: 0.6 | -0.3 |

| China | 1.9 | 7.9 |

| Euro Area | -0.5 | -1.0 |

| Germany | -0.5 | 0.0 |

| France | -0.2 | -0.3 |

| Italy | -0.9 | -3.0 |

| United Kingdom | -0.1 | 0.2 |

| IQ2013/IVQ2012 | IQ2013/IQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 1.1 SAAR: 4.5 | 0.1 |

| China | 1.5 | 7.7 |

| Euro Area | -0.2 | -1.2 |

| Germany | 0.0 | -1.6 |

| France | -0.1 | -0.4 |

| Italy | -0.6 | -2.5 |

| UK | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| IIQ2013/IQ2013 | IIQ2013/IIQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.6 SAAR: 2.5 | 1.6 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.6 | 1.2 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.5 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | -0.6 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| France | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Italy | -0.3 | -2.2 |

| UK | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| IIIQ2013/IIQ2013 | III/Q2013/ IIIQ2012 | |

| USA | QOQ: 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.3 SAAR: 1.1 | 2.4 |

| China | 2.2 | 7.8 |

| Euro Area | 0.1 | -0.3 |

| Germany | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| France | -0.1 | 0.2 |

| Italy | 0.0 | -1.8 |

| UK | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| IVQ2013/IIIQ2013 | IVQ2013/IVQ2012 | |

| USA | QOQ: 0.8 SAAR: 3.2 | 2.7 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.7 |

| UK | 0.7 | 2.8 |

QOQ: Quarter relative to prior quarter; SAAR: seasonally adjusted annual rate

Source: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

Table V-4 provides two types of data: growth of exports and imports in the latest available months and in the past 12 months; and contributions of net trade (exports less imports) to growth of real GDP. Japan provides the most worrisome data (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations_8763.html http://cmpass ocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/interest-rate-risks-duration-dumping.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/duration-dumping-steepening-yield-curve.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/06/paring-quantitative-easing-policy-and_4699.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/05/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states_24.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/contraction-of-united-states-real_25.html and for GDP http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocreulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/recovery-without-hiring-united-states.html). In Dec 2013, Japan’s exports grew 15.3 percent in 12 months while imports increased 24.7 percent. The second part of Table V-4 shows that net trade deducted 1.3 percentage points from Japan’s growth of GDP in IIQ2012, deducted 2.1 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2012 and deducted 0.6 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2012. Net trade added 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2012, 1.6 percentage points in IQ2013 and 0.6 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.9 percentage points from GDP growth in Japan. In Dec 2013, China exports increased 4.3 percent relative to a year earlier and imports increased 8.3 percent. Germany’s exports decreased 0.9 percent in the month of Dec 2013 and increased 4.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013. Germany’s imports decreased 0.6 percent in the month of Dec and increased 2.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec. Net trade contributed 0.8 percentage points to growth of GDP in IQ2012, contributed 0.4 percentage points in IIQ2012, contributed 0.3 percentage points in IIIQ2012, deducted 0.5 percentage points in IVQ2012, deducted 0.2 percentage points in IQ2012 and added 0.3 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded deducted 0.4 percentage points from Germany’s GDP growth in IIIQ2013. Net trade deducted 0.8 percentage points from UK value added in IQ2012, deducted 0.8 percentage points in IIQ2012, added 0.7 percentage points in IIIQ2012 and subtracted 0.5 percentage points in IVQ2012. In IQ2013, net trade added 0.5 percentage points to UK’s growth of value added and contributed 0.2 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.2 percentage points from UK GDP growth. France’s exports increased 3.5 percent in Dec 2013 while imports increased 1.9 percent. Net traded added 0.1 percentage points to France’s GDP in IIIQ2012 and 0.1 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade deducted 0.1 percentage points from France’s GDP growth in IQ2013 and added 0.1 percentage points in IIQ2013, deducting 0.6 percentage points in IIIQ2013. US exports decreased 1.8 percent in Dec 2013 and goods exports increased 2.1 percent in Jan-Dec 2013 relative to a year earlier but net trade deducted 0.03 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2012 and added 0.68 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade deducted 0.28 percentage points from US GDP growth in IQ2013 and deducted 0.07 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded added 0.14 percentage points to US GDP growth in IIIQ2013. Net trade added 1.33 percentage points to US GDP growth in IVQ2013. Industrial production increased 0.3 percent in Dec 2013 after increasing 1.0 percent in Nov 2013 and increasing 0.3 percent in Oct 2013, with all data seasonally adjusted. The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production rose 0.3 percent in December, its fifth consecutive monthly increase. For the fourth quarter as a whole, industrial production advanced at an annual rate of 6.8 percent, the largest quarterly increase since the second quarter of 2010; gains were widespread across industries. Following increases of 0.6 percent in each of the previous two months, factory output rose 0.4 percent in December and was 2.6 percent above its year-earlier level. The production of mines moved up 0.8 percent; the index has advanced 6.6 percent over the past 12 months. The output of utilities fell 1.4 percent after three consecutive monthly gains. At 101.8 percent of its 2007 average, total industrial production in December was 3.7 percent above its year-earlier level and 0.9 percent above its pre-recession peak in December 2007. Capacity utilization for total industry moved up 0.1 percentage point to 79.2 percent, a rate 1.0 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2012) average.”

In the six months ending in Dec 2013, United States national industrial production accumulated increase of 2.7 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 5.5 percent, which is higher than growth of 3.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013. Excluding growth of 1.0 percent in Nov 2013, growth in the remaining five months from Jul 2012 to Dec 2013 accumulated to 1.1 percent or 2.2 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production fell in one of the past six months. Business equipment accumulated growth of 1.7 percent in the six months from Jun to Nov 2013 at the annual equivalent rate of 4.2 percent, which is higher than growth of 3.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “Capacity utilization for total industry moved up 0.1 percentage point to 79.2 percent, a rate 1.0 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2012) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate with possible acceleration in the past few months.

Manufacturing increased 0.4 percent in Dec 2013 after increasing 0.6 percent in Nov 2013 and increasing 0.6 percent in Oct 2013 seasonally adjusted, increasing 2.5 percent not seasonally adjusted in 12 months ending in Nov 2013, as shown in Table I-2. Manufacturing grew cumulatively 2.0 percent in the six months ending in Dec 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 4.1 percent. Excluding the increase of 0.7 percent in Aug 2013, manufacturing accumulated growth of 1.3 percent from Aug 2013 to Dec 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 3.2 percent. Excluding decline of 0.5 percent in Jul 2013, manufacturing grew 2.5 percent from Aug to Dec 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 6.2 percent. Table I-2 provides a longer perspective of manufacturing in the US. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 into more recent months as shown by 12 months rates of growth. Growth rates appeared to be increasing again closer to 5 percent in Apr-Jun 2012 but deteriorated. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appeared to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession but the pace of manufacturing fell steadily in the past six months with some strength at the margin.

Manufacturing fell 21.9 percent from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increased by 19.6 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2013. Manufacturing output in Dec 2013 is 6.6 percent below the peak in Jun 2007.

Table V-4, Growth of Trade and Contributions of Net Trade to GDP Growth, ∆% and % Points

| Exports | Exports 12 M ∆% | Imports | Imports 12 M ∆% | |

| USA | -1.8 Dec | 2.1 Jan-Dec | 0.3 Dec | -0.3 Jan-Dec |

| Japan | Dec 2013 15.3 Nov 2013 18.4 Oct 2013 18.6 Sep 2013 11.5 Aug 2013 14.7 Jul 2013 12.2 Jun 2013 7.4 May 2013 10.1 Apr 2013 3.8 Mar 2013 1.1 Feb 2013 -2.9 Jan 2013 6.4 Dec -5.8 Nov -4.1 Oct -6.5 Sep -10.3 Aug -5.8 Jul -8.1 | Dec 2013 24.7 Nov 2013 21.1 Oct 2013 26.1 Sep 2013 16.5 Aug 2013 16.0 Jul 2013 19.6 Jun 2013 11.8 May 2013 10.0 Apr 2013 9.4 Mar 2013 5.5 Feb 2013 7.3 Jan 2013 7.3 Dec 1.9 Nov 0.8 Oct -1.6 Sep 4.1 Aug -5.4 Jul 2.1 | ||

| China | 2013 4.3 Dec 12.7 Nov 5.6 Oct -0.3 Sep 7.2 Aug 5.1 Jul -3.1 Jun 1.0 May 14.7 Apr 10.0 Mar 21.8 Feb 25.0 Jan | 2013 8.3 Dec 5.3 Nov 7.6 Oct 7.4 Sep 7.0 Aug 10.9 Jul -0.7 Jun -0.3 May 16.8 Apr 14.1 Mar -15.2 Feb 28.8 Jan | ||

| Euro Area | -2.2 12-M Nov | 0.5 Jan-Nov | -5.5 12-M Nov | -3.6 Jan-Nov |

| Germany | -0.9 Dec CSA | 4.6 Dec | -0.6 Nov CSA | 2.0 Dec |

| France Dec | 3.5 | -0.5 | 1.9 | -1.3 |

| Italy Nov | -1.9 | -3.4 | -2.2 | -6.9 |

| UK | 2.1 Dec | -0.1 Oct-Dec 13 /Dec-Oct 12 | -3.8 Dec | -0.4 Oct-Dec 13/Oct-Dec 12 |

| Net Trade % Points GDP Growth | % Points | |||

| USA | IVQ2013 1.33 IIIQ2013 0.14 IIQ2013 -0.07 IQ2013 -0.28 IVQ2012 +0.68 IIIQ2012 -0.03 IIQ2012 +0.10 IQ2012 +0.44 | |||

| Japan | 0.4 IQ2012 -1.3 IIQ2012 -2.1 IIIQ2012 -0.6 IVQ2012 1.6 IQ2013 0.6 IIQ2013 -1.9 IIIQ2013 | |||

| Germany | IQ2012 0.8 IIQ2012 0.4 IIIQ2012 0.3 IVQ2012 -0.5 IQ2013 -0.2 IIQ2013 0.3 IIIQ2013 -0.4 | |||

| France | 0.1 IIIQ2012 0.1 IVQ2012 -0.1 IQ2013 0.1 IIQ2013 -0.6 IIIQ2013 | |||

| UK | -0.8 IQ2012 -0.8 IIQ2012 +0.7 IIIQ2012 -0.5 IVQ2012 0.5 IQ2013 0.2 IIQ2013 -1.2 IIIQ2013 |

Sources: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/ http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The geographical breakdown of exports and imports of Japan with selected regions and countries is provided in Table V-5 for Dec 2013. The share of Asia in Japan’s trade is more than one-half for 55.0 percent of exports and 43.6percent of imports. Within Asia, exports to China are 19.9 percent of total exports and imports from China 21.6 percent of total imports. While exports to China increased 34.4 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013, imports from China increased 29.2 percent. The second largest export market for Japan in US 2013 is the US with share of 18.5 percent of total exports, which is almost equal to that of China, and share of imports from the US of 7.3 percent in total imports. Western Europe has share of 11.1 percent in Japan’s exports and of 10.4 percent in imports. Rates of growth of exports of Japan in Dec 2013 are relatively high for several countries and regions with growth of 13.0 percent for exports to the US, 17.9 percent for exports to Brazil and 28.9 percent for exports to Germany. Comparisons relative to 2011 may have some bias because of the effects of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Deceleration of growth in China and the US and threat of recession in Europe can reduce world trade and economic activity. Growth rates of imports in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 are positive for all trading partners. Imports from Asia increased 23.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 while imports from China increased 29.2 percent. Data are in millions of yen, which may have effects of recent depreciation of the yen relative to the United States dollar (USD).

Table V-5, Japan, Value and 12-Month Percentage Changes of Exports and Imports by Regions and Countries, ∆% and Millions of Yen

| Dec 2013 | Exports | 12 months ∆% | Imports Millions Yen | 12 months ∆% |

| Total | 6,110,510 | 15.3 | 7,412,623 | 24.7 |

| Asia | 3,359,323 | 16.0 | 3,229,984 | 23.0 |

| China | 1,216,540 | 34.4 | 1,600,018 | 29.2 |

| USA | 1,130,094 | 13.0 | 538,484 | 12.1 |

| Canada | 69,480 | 11.8 | 95,207 | 24.9 |

| Brazil | 41,941 | 17.9 | 91,397 | 32.2 |

| Mexico | 80,305 | 10.0 | 34,642 | 10.7 |

| Western Europe | 680,244 | 21.1 | 772,932 | 32.8 |

| Germany | 178,763 | 28.9 | 243,003 | 61.2 |

| France | 62,457 | 46.7 | 89,445 | 15.3 |

| UK | 108,821 | 14.9 | 55,278 | 19.6 |

| Middle East | 241,152 | 22.8 | 1,520,673 | 21.5 |

| Australia | 124,598 | -4.6 | 450,442 | 26.6 |

Source: Japan, Ministry of Finance

http://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/index_e.htm

World trade projections of the IMF are in Table V-6. There is increasing growth of the volume of world trade of goods and services from 2.9 percent in 2013 to 5.4 percent in 2015 and 5.1 percent on average from 2013 to 2018. World trade would be slower for advanced economies while emerging and developing economies (EMDE) experience faster growth. World economic slowdown would more challenging with lower growth of world trade.

Table V-6, IMF, Projections of World Trade, USD Billions, USD/Barrel and ∆%

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average ∆% 2013-2018 | |

| World Trade Volume (Goods and Services) | 2.9 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| Exports Goods & Services | 3.0 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| Imports Goods & Services | 2.8 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| Oil Price USD/Barrel | 104.49 | 101.35 | NA | NA |

| Value of World Exports Goods & Services $B | 23,164 | 24,367 | NA | NA |

| Value of World Exports Goods $B | 18,709 | 19,632 | NA | NA |

| Exports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | 3.5 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 5.9 |

| G7 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Imports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | 5.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 6.2 |

| G7 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.0 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.5 |

| G7 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods | ||||

| EMDE | -0.6 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -0.8 |

| G7 | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.007 |

Notes: Commodity Price Index includes Fuel and Non-fuel Prices; Commodity Industrial Inputs Price includes agricultural raw materials and metal prices; Oil price is average of WTI, Brent and Dubai

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

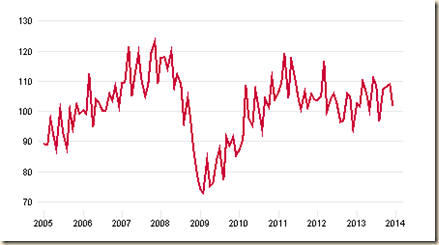

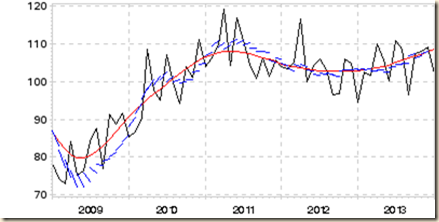

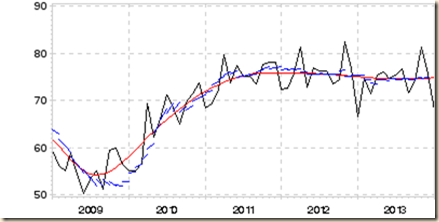

The JP Morgan Global All-Industry Output Index of the JP Morgan Manufacturing and Services PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, with high association with world GDP, increased to 53.9 in Jan from 53.8 in Dec, indicating expansion at almost unchanged rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2dbfcfb799994f3fb94f1a224708ae76). This index has remained above the contraction territory of 50.0 during 54 consecutive months. The employment index decreased from 52.2 in Dec to 51.9 in Jn with input prices rising at a faster rate, new orders increasing at slower rate and output increasing at faster rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2dbfcfb799994f3fb94f1a224708ae76). David Hensley, Director of Global Economics Coordination at JP Morgan finds expectations of continuing growth in 2014 with world GDP expanding quarter-on-quarter at a rate above 3.0 percent in annual equivalent (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2dbfcfb799994f3fb94f1a224708ae76). The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, was almost unchanged at 52.9 in Jan from 53.0 in Dec (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2abe878b5055447b89a369e17c8f4b8b). New export orders expanded at the lowest rate since Sep 2013 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2abe878b5055447b89a369e17c8f4b8b). David Hensley, Director of Global Economic Coordination at JP Morgan finds continuing growth of output and new orders at rates above average in the expansion period (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2abe878b5055447b89a369e17c8f4b8b). The HSBC Brazil Composite Output Index, compiled by Markit, decreased from 51.7 in Dec to 49.9 in Jan, indicating unchanged activity of Brazil’s private sector (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/30abb6a91285494d98cf5a24e2cad184). The HSBC Brazil Services Business Activity index, compiled by Markit, decreased from 51.7 in Dec to 49.6 in Jan, indicating contraction of services activity (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/30abb6a91285494d98cf5a24e2cad184). André Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil, at HSBC, finds slower services activity together with faster inflation of inputs and outputs (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/30abb6a91285494d98cf5a24e2cad184). The HSBC Brazil Purchasing Managers’ IndexTM (PMI™) increased marginally from 50.5 in Dec to 50.8 in Jan, indicating marginal improvement in manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5dd1bda2fcb741929f8b24b035b07cef). André Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil at HSBC, finds improvement with slower growth of production compensated by stronger growth of new orders (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5dd1bda2fcb741929f8b24b035b07cef).

VA United States. The Markit Flash US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) seasonally adjusted decreased to 53.7 in Jan from 55.0 in Dec, which is slightly higher than the average at 53.5 in 2013, indicating moderate growth (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/bda141f5c50642788bf2733f4522f28c). New export orders registered 48.9 in Jan, falling from 51.4 in Dec, indicating marginal contraction. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that manufacturing output is growing at 2.0 percent per quarter with positive effects on employment (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/bda141f5c50642788bf2733f4522f28c). The Markit Flash US Services PMI™ Business Activity Index increased from 55.7 in Dec to 56.6 in Jan (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/979201249645452086dde674d0d375e0). Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that the surveys are consistent with growth of jobs at monthly rate of 200,000 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/979201249645452086dde674d0d375e0). The Markit US Composite PMI™ Output Index of Manufacturing and Services increased marginally to 56.2 in Jan from 56.1 in Dec (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2c3bb316dbb44b348a768fcc4a9713cc). The Markit US Services PMI™ Business Activity Index increased marginally from 55.7 in Dec to 56.7 in Jan (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2c3bb316dbb44b348a768fcc4a9713cc). Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds monthly growth of jobs around 200,000 with 10,000 in manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/2c3bb316dbb44b348a768fcc4a9713cc). The Markit US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) decreased to 53.7 in Jan from 55.0 in Dec, which indicates expansion at slower rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5519007b6dce46c9929b534d255298fd). The index of new exports orders decreased from 51.4 in Dec to 48.4 in Jan while total new orders decreased from 56.1 in Dec to 53.9 in Jan. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that the index suggests slowest growth in three months with respondents mentioning weather but underlying strength with no effects on the economy from Fed tapering of quantitative easing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/5519007b6dce46c9929b534d255298fd). The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) of the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Report on Business® decreased 5.2 percentage points from 56.5 in Dec to 51.3 in Jan, which indicates growth at a slower rate (http://www.ism.ws/ISMReport/MfgROB.cfm?navItemNumber=12942). The index of new orders increased 3.0 percentage points from 60.6 in Oct to 63.6 in Nov. The index of exports decreased 13.2 percentage point from 64.4 in Dec to 51.2 in Nov, growing at a slower rate. The Non-Manufacturing ISM Report on Business® PMI increased 1.0 percentage points from 53.0 in Dec to 54.0 in Jan, indicating growth of business activity/production during 54 consecutive months, while the index of new orders increased 0.5 percentage points from 50.4 in Dec to 50.9 in Jan (http://www.ism.ws/ISMReport/NonMfgROB.cfm?navItemNumber=12943). Table USA provides the country economic indicators for the US.

Table USA, US Economic Indicators

| Consumer Price Index | Dec 12 months NSA ∆%: 1.5; ex food and energy ∆%: 1.7 Dec month SA ∆%: 0.3; ex food and energy ∆%: 0.1 |

| Producer Price Index | Dec 12-month NSA ∆%: 1.2; ex food and energy ∆% 1.4 |

| PCE Inflation | Dec 12-month NSA ∆%: headline 1.1; ex food and energy ∆% 1.2 |

| Employment Situation | Household Survey: Dec Unemployment Rate SA 6.6% |

| Nonfarm Hiring | Nonfarm Hiring fell from 63.8 million in 2006 to 52.0 million in 2012 or by 11.8 million |

| GDP Growth | BEA Revised National Income Accounts IIQ2012/IIQ2011 2.8 IIIQ2012/IIIQ2011 3.1 IVQ2012/IVQ2011 2.0 IQ2013/IQ2012 1.3 IIQ2013/IIQ2012 1.6 IIIQ2013/IIIQ2012 2.0 IVQ2013/IVQ2012 2.7 IQ2012 SAAR 3.7 IIQ2012 SAAR 1.2 IIIQ2012 SAAR 2.8 IVQ2012 SAAR 0.1 IQ2013 SAAR 1.1 IIQ2013 SAAR 2.5 IIIQ2013 SAAR 4.1 IVQ2013 SAAR 3.2 |

| Real Private Fixed Investment | SAAR IIIQ2013 0.9 ∆% IVQ2007 to IIIQ2013: minus 3.4% Blog 2/2/14 |

| Personal Income and Consumption | Dec month ∆% SA Real Disposable Personal Income (RDPI) SA ∆% minus 0.2 |

| Quarterly Services Report | IIIQ13/IIQ12 NSA ∆%: Financial & Insurance 0.6 |

| Employment Cost Index | Compensation Private IVQ2013 SA ∆%: 0.5 |

| Industrial Production | Dec month SA ∆%: 0.3 Manufacturing Dec SA ∆% 0.4 Dec 12 months SA ∆% 2.6, NSA 2.5 |

| Productivity and Costs | Nonfarm Business Productivity IVQ2013∆% SAAE 3.3; IVQ2013/IVQ2012 ∆% 1.7; Unit Labor Costs SAAE IVQ2013 ∆% -1.6; IVQ2013/IVQ2012 ∆%: -1.3 Blog 2/9/2014 |

| New York Fed Manufacturing Index | General Business Conditions From Dec 2.22 to Jan 12.51 |

| Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook Index | General Index from Dec 6.4 to Jan 9.4 |

| Manufacturing Shipments and Orders | New Orders SA Dec ∆% -1.5 Ex Transport 0.2 Jan-Dec NSA New Orders ∆% 2.5 Ex transport 1.5 |

| Durable Goods | Dec New Orders SA ∆%: minus 4.3; ex transport ∆%: minus 1.6 |

| Sales of New Motor Vehicles | Jan 2014 1,012,582; Jan 2013 1,044,655. Jan 14 SAAR 15.24 million, Dec 13 SAAR 15.40 million, Jan 2013 SAAR 15.23 million Blog 2/9/14 |

| Sales of Merchant Wholesalers | Jan-Nov 2013/Jan-Nov 2012 NSA ∆%: Total 3.7; Durable Goods: 3.9; Nondurable |

| Sales and Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers | Nov 13/Nov 12-M NSA ∆%: Sales Total Business 2.5; Manufacturers 1.7 |

| Sales for Retail and Food Services | Jan-Dec 2013/Jan-Dec 2012 ∆%: Retail and Food Services 4.2; Retail ∆% 4.2 |

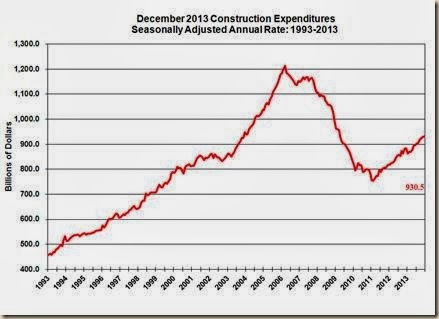

| Value of Construction Put in Place | Dec SAAR month SA ∆%: 0.1 Dec 12-month NSA: 3.1 Jan-Dec 2013 ∆% 4.8 |

| Case-Shiller Home Prices | Nov 2013/Nov 2012 ∆% NSA: 10 Cities 13.8; 20 Cities: 13.7 |

| FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only | Nov SA ∆% 0.1; |

| New House Sales | Dec 2013 month SAAR ∆%: minus 7.0 |

| Housing Starts and Permits | Dec Starts month SA ∆% -9.8; Permits ∆%: -3.0 |

| Trade Balance | Balance Nov SA -$24,252 million versus Oct -$39,328 million |

| Export and Import Prices | Dec 12-month NSA ∆%: Imports -1.3; Exports -1.0 |

| Consumer Credit | Nov ∆% annual rate: Total 4.8; Revolving 0.6; Nonrevolving 6.4 |

| Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term Treasury Securities | Nov Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term US Securities: -$29.3 billion |

| Treasury Budget | Fiscal Year 2014/2013 ∆% Dec: Receipts 8.0; Outlays minus 7.8; Individual Income Taxes -1.9 Deficit Fiscal Year 2012 $1,089 billion Blog 1/19/2014 |

| CBO Budget and Economic Outlook | 2012 Deficit $1087 B 6.8% GDP Debt 11,281 B 70.1% GDP 2013 Deficit $642 B, Debt 12,036 B 72.5% GDP Blog 8/26/12 11/18/12 2/10/13 9/22/13 |

| Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities | Dec 2013 SAAR ∆%: Securities 11.7 Loans 3.7 Cash Assets -9.0 Deposits 9.4 Blog 1/26/14 |

| Flow of Funds | IIIQ2013 ∆ since 2007 Assets +$8554.2 MM Nonfinancial -$1228.7 MM Real estate -$1838.9 MM Financial +9782.9 MM Net Worth +$9269.0 MM Blog 12/29/13 |

| Current Account Balance of Payments | IIIQ2013 -110,055 MM %GDP 2.2 Blog 12/22/13 |

Links to blog comments in Table USA:

2/2/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html

1/26/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html

1/19/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/world-inflation-waves-interest-rate.html

1/12/14 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html

12/29/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html

12/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html

12/15/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html

11/24/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html

9/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

2/10/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the US Department of Labor provides the quarterly employment cost index (ECI). The ECI is highly useful in several ways including: (1) how costs of employees may affect hiring decisions and thus the overall economy; (2) impact of employment costs on inflation and thus monetary policy; and (3) relation of employee costs to inflation on issues such as welfare of the working population and their ability to consume that could affect economic growth. The BLS estimates total compensation composed of wages and salaries, which are about 70 percent of total compensation, and benefits, accounting for the remaining 30 percent (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/eci.pdf 1). There is vast theoretical and empirical literature on how benefits interact with wage determination. The ECI is considered initially with current data in Table VA-1 and subsequently with charts of the BLS on evolution over the past decade. The BLS provides data for the entire civilian population, the private sector and state/local government. The data are available quarterly and for the 12 months of the ending month of the quarter. Total compensation 12-month percentage changes have moderated for the entire civilian population, the private sector and state and local government. In the 12 months ending in Dec 2013, total compensation increased 1.8 percent for the private sector, which is marginally higher than inflation of 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm), 1.9 percent for the entire civilian population and 1.9 percent for state and local government. Wages and salaries in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 increased at relatively subdued rates of 1.7 percent for the private sector, which is slightly above inflation of 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm), 1.7 percent for the entire civilian population and only 1.1 percent for state/local workers. Wages have been losing or gaining slightly relative to headline CPI inflation of 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm). Compensation benefits of the private sector increased at 2.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013, which is close to 1.7 percent for wages and salaries.

Table VA-1, Employment Cost Index Quarterly and 12- Month Changes %

| IIIQ13 SA | IVQ13 SA | 12 M | 12 M Mar 13 NSA | 12 M | 12 M | 12 M Dec 13 | |

| Civilian | |||||||

| Comp | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Wages/ | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Benefits | 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Private | |||||||

| Comp | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Wages/ | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Benefits | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| State local | |||||||

| Comp | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Wages/ | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Benefits | 0.5 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.3 |

Notes: Civilian includes private industry plus state and local government; SA: seasonally adjusted; NSA: not seasonally adjusted; Comp: compensation; Govt: government

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ect/

A series of charts of the BLS provides evolution of the ECI during the past decade. Percentage changes in 12 months of total civilian compensation in Chart VA-1 were in a range of around 3 to 4 percent before the global recession, declining to less than 2 percent with the contraction and increasing above 2 percent in the expansion. Recently, rates have fallen, stagnated, fell again, recovered and stabilized.

Chart VA-1, US, ECI, Total Compensation, All Civilian, 12-Month Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart VA-2 provides 12 months percentage rates of change of wages and salaries for the entire civilian population. The rates collapsed with the global recession and have flattened around 1.5 percent since 2010 while inflation has accelerated and decelerated following world inflation waves (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/world-inflation-waves-interest-rate.html).

Chart VA-2, US, ECI, Wages and Salaries, All Civilian 12-Month Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Twelve-month percentage changes of benefits of the total civilian population in Chart VA-3 were much higher in the first part of the 2000s, surpassing relatively subdued inflation but declined to less than 2 percent with the global recession. After 2010, there is a clear rising trend of benefit above 3 percent with decline in recent months of 2011 and then stagnation and declines in 2012-2013.

Chart VA-3, US, ECI, Total Benefits, All Civilian 12 Months Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

ECI total compensation 12-months percentage changes from 2001 to 2013 for the private sector are shown in Chart VA-4. Behavior is similar as for total civilian compensation. Private-sector compensation had stabilized around 2 percent with inflation rising to 2.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2012. Compensation increase of 1.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2013 exceeded 12-month inflation of 1.5 percent. Compensation increased 1.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2013, almost equal to 12-month CPI inflation of 1.8 percent. Compensation at 1.9 percent in Sep 2013 exceeded 12-month CPI inflation of 1.2 percent. Compensation of 2.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 exceeded CPI inflation of 1.5 percent.

Chart VA-4, US, ECI, Total Compensation, Private Industry 12 Months Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

There is different behavior of 12 months percentage rates of private-sector wages and salaries in Chart VA-5. Rates fell in the first part of the decade and then rose into 2007. Rates of change in 12 months of wages and salaries in the private sector fell during the global contraction to barely above 1 percent and have not rebounded sufficiently while inflation has returned in waves.

Chart VA-5, US, ECI, Wages and Salaries, Private Industry, 12 Months Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart VA-6 provides 12-month percentage rates of change of the consumer price index of the US. Inflation has risen sharply into 2011 with 3.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec while wage and salary increases in the private sector have risen by 1.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec. Wages and salaries rose 1.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2012 while inflation was 2.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2012. Wage and salaries of the private sector increased 1.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2012, which is almost equal to inflation of 1.7 percent. Wages and salaries increased 1.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2012 while inflation was 2.0 percent. Wages and salaries increased 1.7 percent in Dec 2012 while inflation was 1.7 percent. Wages and salaries increased 1.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2013 while inflation was 1.5 percent. Wages and salaries increased 1.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2013 while inflation was 1.8 percent. The increase of wages and salaries of 1.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2013 exceeded inflation of 1.2 percent. Wages and salaries increased 2.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013, exceeding CPI inflation of 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013.

Chart VA-6, US, Consumer Price Index, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Growth of benefits has been more dynamic than total compensation and wages and salaries, as shown in Chart VA-7. In 2004, the 12 month rate of change exceeded 7 percent. Rates of increase of benefits costs then fell even before the global recession, touching 1 percent in late 2010, rose sharply above 3 percent in 2011 and have fallen in recent months to around 2 percent.

Chart VA-7, US, ECI, Total Benefits, Private Industry, 12 Months Percent Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Behavior at the margin is provided by rates of change in a quarter relative to the prior quarter, as shown in Chart VA-8. Quarterly rates of change of total civilian compensation were high in the early 2000s, fell sharply with the global recession, recovered mildly and stagnated in recent quarters.

Chart VA-8, US, Employment Cost Index All Civilian Total Compensation Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

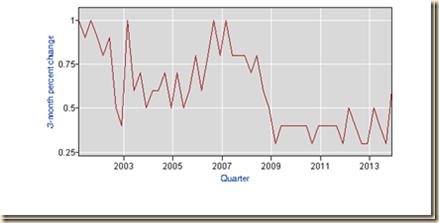

Chart VA-9 provides the quarterly rates of change of wages and salaries of the entire civilian population. The rates of change sank below 0.5 percent per quarter and have remained subdued since the global recession.

Chart VA-9, US, ECI, Wages and Salaries, All Civilian, Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Quarterly rates of change of benefits of the total civilian population in Chart VA-10 had declined before the global recession. The rate collapsed in recent quarters.

Chart VA-10, US, ECI, Total Benefits, All Civilian, Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Quarterly rates of change of total compensation of the private sector in Chart VA-11 have not returned to the levels before the contraction except with sporadic jump in 2011 followed by contraction and stagnation in recent quarters.

Chart VA-11, US, ECI, Total Compensation, Private Industry, Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

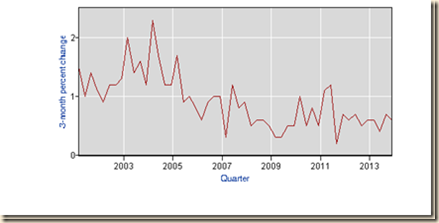

Quarterly rates of change of wages and salaries of the private sector in Chart VA-12 show significant fluctuation. Quarterly rates of change have fallen below 0.5 percent in the current expansion.

Chart VA-12, US, ECI, Wages and Salaries, Private Industry, Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The three-month rates of change of benefits of private industry in Chart VA-13 have fluctuated widely with the only negative change in 2007. The 12-month rate of private-sector benefits fell in past months.

VA-13, US, ECI, Total Benefits, Private Industry, Three-Month % Change, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the Department of Labor provides the quarterly report on productivity and costs. The operational definition of productivity used by the BLS is (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prod2.pdf 1): “Labor productivity, or output per hour, is calculated by dividing an index of real output by an index of hours worked of all persons, including employees, proprietors, and unpaid family workers.” The BLS has revised the estimates for productivity and unit costs. Table VA-2 provides the new estimate for IVQ2013 and revised data for nonfarm business sector productivity and unit labor costs for IIIQ2013 and IIQ2013 in seasonally adjusted annual equivalent (SAAE) rate and the percentage change from the same quarter a year earlier. Reflecting increases in output of 4.9 percent and of 1.7 percent in hours worked, nonfarm business sector labor productivity increased at a SAAE rate of 3.2 percent in IVQ2013, as shown in column 2 “IVQ2013 SAEE.” The increase of labor productivity from IVQ2012 to IVQ2013 was 1.7 percent, reflecting increases in output of 3.3 percent and of hours worked of 1.6 percent, as shown in column 3 “IVQ2013 YoY.” Hours worked increased from 1.4 percent in IIQ2013 in SAAE to 1.7 percent in IIIQ2013 and 1.7 percent in IVQ2013 while output growth increased from 3.3 percent in IIQ2013 to 5.4 percent in IIIQ2013 and 4.9 percent in IVQ2013. The BLS defines unit labor costs as (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prod2.pdf 1): “BLS defines unit labor costs as the ratio of hourly compensation to labor productivity; increases in hourly compensation tend to increase unit labor costs and increases in output per hour tend to reduce them.” Unit labor costs increased at the SAAE rate of 1.5 percent in IVQ2013 and rose 0.4 percent in IVQ2013 relative to IVQ2012. Hourly compensation increased at the SAAE rate of 1.5 percent in IVQ2013, which deflating by the estimated consumer price increase SAAE rate in IVQ2013 results in increase of real hourly compensation at 0.6 percent. Real hourly compensation decreased 0.9 percent in IVQ2013 relative to IVQ2012.

Table VA-2, US, Nonfarm Business Sector Productivity and Costs %

| IVQ 2013 SAAE | IVQ 2013 YoY | IIIQ 2013 SSAE | IIIQ 2013 YOY | IIQ | IIQ | |

| Productivity | 3.2 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Output | 4.9 | 3.3 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| Hours | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Hourly | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.2 |

| Real Hourly Comp. | 0.6 | -0.9 | -1.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 0.7 |

| Unit Labor Costs | -1.6 | -1.3 | -2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Unit Nonlabor Payments | 4.6 | 4.7 | 8.4 | 0.3 | -0.7 | 0.1 |

| Implicit Price Deflator | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

Notes: SAAE: seasonally adjusted annual equivalent; Comp.: compensation; YoY: Quarter on Same Quarter Year Earlier

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The analysis by Kydland (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2004/kydland-facts.html) and Prescott (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2004/prescott-bio.html) (1977, 447-80, equation 5) uses the “expectation augmented” Phillips curve with the natural rate of unemployment of Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968), which in the notation of Barro and Gordon (1983, 592, equation 1) is:

Ut = Unt – α(πt – πe) α > 0 (1)

Where Ut is the rate of unemployment at current time t, Unt is the natural rate of unemployment, πt is the current rate of inflation and πe is the expected rate of inflation by economic agents based on current information. Equation (1) expresses unemployment net of the natural rate of unemployment as a decreasing function of the gap between actual and expected rates of inflation. The system is completed by a social objective function, W, depending on inflation, π, and unemployment, U:

W = W(πt, Ut) (2)

The policymaker maximizes the preferences of the public, (2), subject to the constraint of the tradeoff of inflation and unemployment, (1). The total differential of W set equal to zero provides an indifference map in the Cartesian plane with ordered pairs (πt, Ut - Un) such that the consistent equilibrium is found at the tangency of an indifference curve and the Phillips curve in (1). The indifference curves are concave to the origin. The consistent policy is not optimal. Policymakers without discretionary powers following a rule of price stability would attain equilibrium with unemployment not higher than with the consistent policy. The optimal outcome is obtained by the rule of price stability, or zero inflation, and no more unemployment than under the consistent policy with nonzero inflation and the same unemployment. Taylor (1998LB) attributes the sustained boom of the US economy after the stagflation of the 1970s to following a monetary policy rule instead of discretion (see Taylor 1993, 1999). It is not uncommon for effects of regulation differing from those intended by policy. Professors Edward C. Prescott and Lee E. Ohanian (2014Feb), writing on “US productivity growth has taken a dive,” on Feb 3, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303942404579362462611843696?KEYWORDS=Prescott), argue that impressive productivity growth over the long-term constructed US prosperity and wellbeing. Prescott and Ohanian (2014Feb) measure US productivity growth at 2.5 percent per year since 1948. Average US productivity growth has been only 1.1 percent on average since 2011. Prescott and Ohanian (2014Feb) argue that living standards in the US increased at 28 percent in a decade but with current slow growth of productivity will only increase 12 percent by 2024. There may be collateral effects on productivity growth from policy design similar to those in Kydland and Prescott (1977). The Bureau of Labor Statistics important report on productivity and costs released on Feb 6, 2014 (http://www.bls.gov/lpc/) supports the argument of decline of productivity in the US analyzed by Prescott and Ohanian (2014Feb). Table VA-3 provides the annual percentage changes of productivity, real hourly compensation and unit labor costs for the entire economic cycle from 2007 to 2013. The data confirm the argument of Prescott and Ohanian (2014Feb): productivity increased cumulatively 2.6 percent from 2011 to 2013 at the average annual rate of 0.9 percent. The situation is direr by excluding growth of 1.5 percent in 2012, which leaves an average of 0.55 percent for 2011 and 2013. Average productivity growth for the entire economic cycle from 2007 to 2013 is only 1.6 percent. The argument by Prescott and Ohanian (2014Feb) is proper in choosing the tail of the business cycle because the increase in productivity in 2009 of 3.2 percent and 3.3 percent in 2013 consisted on reducing labor hours.

Table VA-3, US, Revised Nonfarm Business Sector Productivity and Costs Annual Average, ∆% Annual Average

| 2013 ∆% | 2012 ∆% | 2011 ∆% | 2010 ∆% | 2009 ∆% | 2008 ∆% | 2007 ∆% | |

| Productivity | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Real Hourly Compensation | 0.2 | 0.5 | -0.7 | 0.4 | 1.5 | -1.1 | 1.4 |

| Unit Labor Costs | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.0 | -1.2 | -2.0 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Productivity jumped in the recovery after the recession from Mar IQ2001 to Nov IVQ2001 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). Table VA-4 provides quarter on quarter and annual percentage changes in nonfarm business output per hour, or productivity, from 1999 to 2013. The annual average jumped from 2.7 percent in 2001 to 4.3 percent in 2002. Nonfarm business productivity increased at the SAAE rate of 9.5 percent in the first quarter after the recession in IQ2002. Productivity increases decline later in the expansion period. Productivity increases were mediocre during the recession from Dec IVQ2007 to Jun IIIQ2009 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html) and increased during the first phase of expansion from IIQ2009 to IQ2010, trended lower and collapsed in 2011 and 2012 with sporadic jumps and declines. Productivity increased at 3.2 percent in IVQ2013.

Table VA-4, US, Nonfarm Business Output per Hour, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate, 1999-2013

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

| 2000 | -1.4 | 8.7 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 3.3 |

| 2001 | -1.2 | 6.8 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 2.7 |

| 2002 | 9.5 | 0.3 | 3.1 | -0.7 | 4.3 |

| 2003 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 9.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| 2004 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| 2005 | 4.6 | -0.3 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| 2006 | 2.6 | -0.3 | -1.8 | 3.2 | 0.9 |

| 2007 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| 2008 | -3.9 | 4.0 | 0.9 | -2.6 | 0.8 |

| 2009 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 3.2 |

| 2010 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.3 |

| 2011 | -3.2 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.5 |

| 2012 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.5 | -1.7 | 1.5 |

| 2013 | -1.7 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart VA-14 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides SAAE rates of nonfarm business productivity from 1999 to 2013. There is a clear pattern in both episodes of economic cycles in 2001 and 2007 of rapid expansion of productivity in the transition from contraction to expansion followed by more subdued productivity expansion. Part of the explanation is the reduction in labor utilization resulting from adjustment of business to the sudden shock of collapse of revenue. Productivity rose briefly in the expansion after 2009 but then collapsed and moved to negative change with some positive changes recently at lower rates.

Chart VA-14, US, Nonfarm Business Output per Hour, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate, 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

Percentage changes from prior quarter at SAAE rates and annual average percentage changes of nonfarm business unit labor costs are provided in Table VA-5. Unit labor costs fell during the contractions with continuing negative percentage changes in the early phases of the recovery. Weak labor markets partly explain the decline in unit labor costs. As the economy moves toward full employment, labor markets tighten with increase in unit labor costs. The expansion beginning in IIIQ2009 has been characterized by high unemployment and underemployment. Table VA-4 shows continuing subdued increases in unit labor costs in 2011 but with increase of 7.4 percent in IQ2012 followed by increase of 0.7 percent in IIQ2012, decline of 1.8 percent in IIIQ2012 and increase of 11.8 percent in IVQ2012. Unit labor costs decreased at 3.5 percent in IQ2013 and increased 2.0 percent in IIQ2013. Unit labor costs decreased at 1.0 percent in IIIQ2013 and at 1.6 percent in IVQ2013.

Table VA-5, US, Nonfarm Business Unit Labor Costs, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2013

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 2.0 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| 2000 | 17.4 | -6.8 | 8.2 | -1.6 | 4.0 |

| 2001 | 11.4 | -5.4 | -1.7 | -1.3 | 1.6 |

| 2002 | -6.7 | 3.3 | -1.1 | 1.8 | -1.9 |

| 2003 | -1.4 | 1.5 | -2.7 | 1.7 | 0.1 |

| 2004 | -0.6 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| 2005 | -1.5 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| 2006 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| 2007 | 9.8 | -2.7 | -3.2 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| 2008 | 8.2 | -3.6 | 2.5 | 7.3 | 2.0 |

| 2009 | -12.3 | 1.9 | -2.9 | -2.2 | -2.0 |

| 2010 | -4.4 | 3.5 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -1.2 |

| 2011 | 10.2 | -2.9 | 3.0 | -7.3 | 2.0 |

| 2012 | 7.4 | 0.7 | -1.8 | 11.8 | 1.2 |

| 2013 | -3.5 | 2.0 | -2.0 | -1.6 | 1.0 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

Chart VA-15 provides percentage change from prior quarter at annual rate of nonfarm business real hourly compensation from 1999 to 2013. There are significant fluctuations in quarterly percentage changes oscillating between positive and negative. There is no clear pattern in the two contractions in the 2000s.

Chart VA-15, US, Nonfarm Business Unit Labor Costs, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

Table VA-6 provides percentage change from prior quarter at annual rates for nonfarm business real hourly worker compensation. The expansion after the contraction of 2001 was followed by strong recovery of real hourly compensation. Real hourly compensation increased at the rate of 2.1 percent in IQ2011 but fell at annual rates of 5.4 percent in IIQ2011 and 5.9 percent in IVQ2011. Real hourly compensation increased at 6.5 percent in IQ2012 and at 0.9 percent in IIQ2012, declining at 1.3 percent in IIIQ2012 and increasing at 7.5 percent in IVQ2012. Real hourly compensation fell 0.7 percent in 2011 and increased 0.5 percent in 2012. Real hourly compensation fell at 6.6 percent in IQ2013 and increased at 3.9 percent in IIQ2013, falling at 1.0 percent in IIIQ2013. Real hourly compensation increased at 0.6 percent in IVQ2013.

Table VA-6, Nonfarm Business Real Hourly Compensation, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2013

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 5.1 | -1.9 | 0.3 | 5.5 | 2.1 |

| 2000 | 11.5 | -1.8 | 4.4 | -0.5 | 3.9 |

| 2001 | 6.0 | -1.8 | -0.7 | 4.0 | 1.5 |

| 2002 | 0.7 | 0.4 | -0.2 | -1.4 | 0.7 |

| 2003 | -1.5 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 1.5 |

| 2004 | -3.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 | -2.5 | 1.8 |

| 2005 | 1.2 | -0.6 | -1.1 | -1.2 | 0.3 |

| 2006 | 6.5 | -3.3 | -3.4 | 9.2 | 0.6 |

| 2007 | 6.0 | -4.5 | -1.2 | -0.5 | 1.4 |

| 2008 | -0.5 | -4.7 | -2.7 | 14.7 | -1.1 |

| 2009 | -7.1 | 8.2 | -0.8 | -0.8 | 1.5 |

| 2010 | -3.3 | 5.3 | 0.9 | -1.0 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 2.1 | -5.4 | 0.0 | -5.9 | -0.7 |

| 2012 | 6.5 | 0.9 | -1.3 | 7.5 | 0.5 |

| 2013 | -6.6 | 3.9 | -1.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart VA-16 provides percentage change from prior quarter at annual rate of nonfarm business real hourly compensation. There have been multiple negative percentage quarterly changes in the current cycle from IvQ2007.

Chart VA-16, US, Nonfarm Business Real Hourly Compensation, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

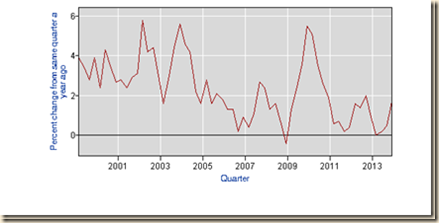

Chart VA-17 provides percentage change of nonfarm business output per hour in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. As in most series of real output, productivity increased sharply in 2010 but the momentum was lost after 2011 as with the rest of the real economy.

Chart VA-17, US, Nonfarm Business Output per Hour, Percent Change from Same Quarter a Year Earlier 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

Chart VA-18 provides percentage changes of nonfarm business unit labor costs relative to the same quarter a year earlier. Softening of labor markets caused relatively high yearly percentage changes in the recession of 2001 repeated in the recession in 2009. Recovery was strong in 2010 but then weakened.

Chart VA-18, US, Nonfarm Business Unit Labor Costs, Percent Change from Same Quarter a Year Earlier 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

Chart VA-19 provides percentage changes in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier for nonfarm business real hourly compensation. Labor compensation eroded sharply during the recession with brief recovery in 2010 and another fall until recently.

Chart VA-19, US, Nonfarm Business Real Hourly Compensation, Percent Change from Same Quarter a Year Earlier 1999-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/

In the analysis of Hansen (1939, 3) of secular stagnation, economic progress consists of growth of real income per person driven by growth of productivity. The “constituent elements” of economic progress are “(a) inventions, (b) the discovery and development of new territory and new resources, and (c) the growth of population” (Hansen 1939, 3). Secular stagnation originates in decline of population growth and discouragement of inventions. According to Hansen (1939, 2), US population grew by 16 million in the 1920s but grew by one half or about 8 million in the 1930s with forecasts at the time of Hansen’s writing in 1938 of growth of around 5.3 million in the 1940s. Hansen (1939, 2) characterized demography in the US as “a drastic decline in the rate of population growth. Hansen’s plea was to adapt economic policy to stagnation of population in ensuring full employment. In the analysis of Hansen (1939, 8), population caused half of the growth of US GDP per year. Growth of output per person in the US and Europe was caused by “changes in techniques and to the exploitation of new natural resources.” In this analysis, population caused 60 percent of the growth of capital formation in the US. Declining population growth would reduce growth of capital formation. Residential construction provided an important share of growth of capital formation. Hansen (1939, 12) argues that market power of imperfect competition discourages innovation with prolonged use of obsolete capital equipment. Trade unions would oppose labor-savings innovations. The combination of stagnating and aging population with reduced innovation caused secular stagnation. Hansen (1939, 12) concludes that there is role for public investments to compensate for lack of dynamism of private investment but with tough tax/debt issues.

The current application of Hansen’s (1938, 1939, 1941) proposition argues that secular stagnation occurs because full employment equilibrium can be attained only with negative real interest rates between minus 2 and minus 3 percent. Professor Lawrence H. Summers (2013Nov8) finds that “a set of older ideas that went under the phrase secular stagnation are not profoundly important in understanding Japan’s experience in the 1990s and may not be without relevance to America’s experience today” (emphasis added). Summers (2013Nov8) argues there could be an explanation in “that the short-term real interest rate that was consistent with full employment had fallen to -2% or -3% sometime in the middle of the last decade. Then, even with artificial stimulus to demand coming from all this financial imprudence, you wouldn’t see any excess demand. And even with a relative resumption of normal credit conditions, you’d have a lot of difficulty getting back to full employment.” The US economy could be in a situation where negative real rates of interest with fed funds rates close to zero as determined by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) do not move the economy to full employment or full utilization of productive resources. Summers (2013Oct8) finds need of new thinking on “how we manage an economy in which the zero nominal interest rates is a chronic and systemic inhibitor of economy activity holding our economies back to their potential.”

Former US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin (2014Jan8) finds three major risks in prolonged unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing: (1) incentive of delaying action by political leaders; (2) “financial moral hazard” in inducing excessive exposures pursuing higher yields of risker credit classes; and (3) major risks in exiting unconventional policy. Rubin (2014Jan8) proposes reduction of deficits by structural reforms that could promote recovery by improving confidence of business attained with sound fiscal discipline.

Professor John B. Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) provides clear thought on the lack of relevance of Hansen’s contention of secular stagnation to current economic conditions. The application of secular stagnation argues that the economy of the US has attained full-employment equilibrium since around 2000 only with negative real rates of interest of minus 2 to minus 3 percent. At low levels of inflation, the so-called full-employment equilibrium of negative interest rates of minus 2 to minus 3 percent cannot be attained and the economy stagnates. Taylor (2014Jan01) analyzes multiple contradictions with current reality in this application of the theory of secular stagnation:

- Secular stagnation would predict idle capacity, in particular in residential investment when fed fund rates were fixed at 1 percent from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004. Taylor (2014Jan01) finds unemployment at 4.4 percent with house prices jumping 7 percent from 2002 to 2003 and 14 percent from 2004 to 2005 before dropping from 2006 to 2007. GDP prices doubled from 1.7 percent to 3.4 percent when interest rates were low from 2003 to 2005.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) finds another contradiction in the application of secular stagnation based on low interest rates because of savings glut and lack of investment opportunities. Taylor (2009) shows that there was no savings glut. The savings rate of the US in the past decade is significantly lower than in the 1980s.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) finds another contradiction in the low ratio of investment to GDP currently and reduced investment and hiring by US business firms.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) argues that the financial crisis and global recession were caused by weak implementation of existing regulation and departure from rules-based policies.

- Taylor (2014Jan01, 2014Jan3) argues that the recovery from the global recession was constrained by a change in the regime of regulation and fiscal/monetary policies.

The analysis by Kydland (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2004/kydland-facts.html) and Prescott (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2004/prescott-bio.html) (1977, 447-80, equation 5) uses the “expectation augmented” Phillips curve with the natural rate of unemployment of Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968), which in the notation of Barro and Gordon (1983, 592, equation 1) is:

Ut = Unt – α(πt – πe) α > 0 (1)

Where Ut is the rate of unemployment at current time t, Unt is the natural rate of unemployment, πt is the current rate of inflation and πe is the expected rate of inflation by economic agents based on current information. Equation (1) expresses unemployment net of the natural rate of unemployment as a decreasing function of the gap between actual and expected rates of inflation. The system is completed by a social objective function, W, depending on inflation, π, and unemployment, U:

W = W(πt, Ut) (2)