Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation, Recovery without Hiring, United States Budget Quagmire, United States Industrial Production, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Executive Summary

I Recovery without Hiring

IA1 Hiring Collapse

IA2 Labor Underutilization

ICA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment

IIA United States Budget Quagmire

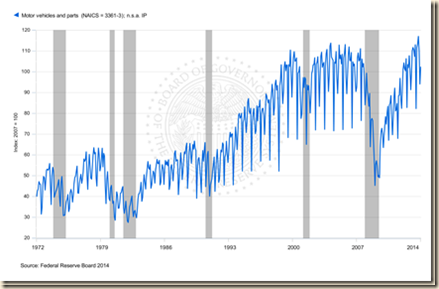

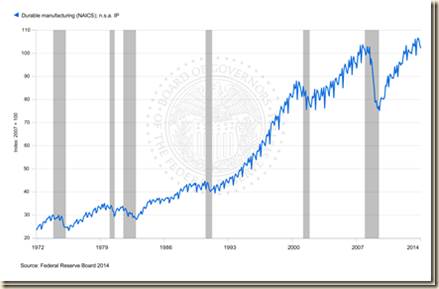

IIB United States Industrial Production

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

I Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels have increased by only 4 percent since Jan 2009. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job currently is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer in the American Economic Review (Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 2012May) on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar amount of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn, there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.htm). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled. There are four subsections. IA1 Hiring Collapse provides the data and analysis on the weakness of hiring in the United States economy. IA2 Labor Underutilization provides the measures of labor underutilization of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Statistics on the decline of full-time employment are in IA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment provides the data on high unemployment of ages 16 to 24 years and of ages 45 years or over.

IA1 Hiring Collapse. An important characteristic of the current fractured labor market of the US is the closing of the avenue for exiting unemployment and underemployment normally available through dynamic hiring. Another avenue that is closed is the opportunity for advancement in moving to new jobs that pay better salaries and benefits again because of the collapse of hiring in the United States. Those who are unemployed or underemployed cannot find a new job even accepting lower wages and no benefits. The employed cannot escape declining inflation-adjusted earnings because there is no hiring. The objective of this section is to analyze hiring and labor underutilization in the United States.

Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53 consider an appropriate measure of job stress:

“The right measure of the state of the labor market is the exit rate from unemployment, defined as the number of hires divided by the number unemployed, rather than the unemployment rate itself. What matters to the unemployed is not how many of them there are, but how many of them there are in relation to the number of hires by firms.”

The natural rate of unemployment and the similar NAIRU are quite difficult to estimate in practice (Ibid; see Ball and Mankiw 2002).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) created the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) with the purpose that (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/jltover.htm#purpose):

“These data serve as demand-side indicators of labor shortages at the national level. Prior to JOLTS, there was no economic indicator of the unmet demand for labor with which to assess the presence or extent of labor shortages in the United States. The availability of unfilled jobs—the jobs opening rate—is an important measure of tightness of job markets, parallel to existing measures of unemployment.”

The BLS collects data from about 16,000 US business establishments in nonagricultural industries through the 50 states and DC. The data are released monthly and constitute an important complement to other data provided by the BLS (see also Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 6-7).

Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 63.8 million in 2006 to 52.0 million in 2012 or by 11.8 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 59.5 million in 2006 to 48.5 million in 2012 or by 11.0 million, as shown in Table I-1. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) has fallen from 47.2 in 2005 to 38.9 in 2012 and in the private sector (RHP) from 53.1 in 2005 to 43.4 in 2012. Hiring has not recovered as in previous cyclical expansions because of the low rate of economic growth in the current cyclical expansion. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Table I-1, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in Thousands and Percentage of Total Employment

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 | 62,948 | 47.8 | 58,825 | 53.1 |

| 2002 | 58,583 | 44.9 | 54,759 | 50.3 |

| 2003 | 56,451 | 43.4 | 53,056 | 48.9 |

| 2004 | 60,367 | 45.9 | 56,617 | 51.6 |

| 2005 | 63,150 | 47.2 | 59,372 | 53.1 |

| 2006 | 63,773 | 46.9 | 59,494 | 52.1 |

| 2007 | 62,421 | 45.4 | 58,035 | 50.3 |

| 2008 | 55,128 | 40.3 | 51,591 | 45.1 |

| 2009 | 46,357 | 35.4 | 43,031 | 39.8 |

| 2010 | 48,607 | 37.4 | 44,788 | 41.7 |

| 2011 | 49,675 | 37.8 | 46,552 | 42.5 |

| 2012 | 51,991 | 38.9 | 48,493 | 43.4 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

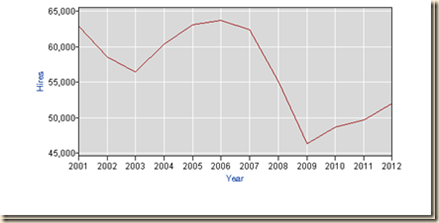

Chart I-1 shows the annual level of total nonfarm hiring (HNF) that collapsed during the global recession after 2007 in contrast with milder decline in the shallow recession of 2001. Nonfarm hiring has not recovered, remaining at a depressed level.

Chart I-1, US, Level Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual, 2001-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

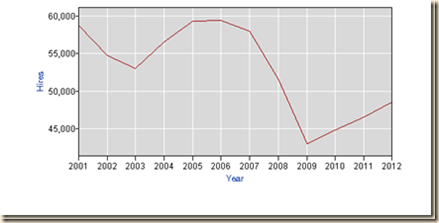

Chart I-2 shows the ratio or rate of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) that also fell much more in the recession of 2007 to 2009 than in the shallow recession of 2001. Recovery is weak in the current environment of cyclical slow growth.

Chart I-2, US, Rate Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual, 2001-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Yearly percentage changes of total nonfarm hiring (HNF) are provided in Table I-2. There were much milder declines in 2002 of 6.9 percent and 3.6 percent in 2003 followed by strong rebounds of 6.9 percent in 2004 and 4.6 percent in 2005. In contrast, the contractions of nonfarm hiring in the recession after 2007 were much sharper in percentage points: 2.1 in 2007, 11.7 in 2008 and 15.9 percent in 2009. On a yearly basis, nonfarm hiring grew 4.9 percent in 2010 relative to 2009, 2.2 percent in 2011 and 4.7 percent in 2012.

Table I-2, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual Percentage Change, 2002-2012

| Year | Annual ∆% |

| 2002 | -6.9 |

| 2003 | -3.6 |

| 2004 | 6.9 |

| 2005 | 4.6 |

| 2006 | 1.0 |

| 2007 | -2.1 |

| 2008 | -11.7 |

| 2009 | -15.9 |

| 2010 | 4.9 |

| 2011 | 2.2 |

| 2012 | 4.7 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Total private hiring (HP) yearly data are provided in Chart I-4. There has been sharp contraction of total private hiring in the US and only milder recovery from 2010 to 2012.

Chart I-4, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring Level, Annual, 12-Month ∆%, 2001-2012

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-5 plots the rate of total private hiring relative to employment (RHP). The rate collapsed during the global recession after 2007 with insufficient recovery.

Chart I-5, US, Total Private Hiring, Annual, 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-5A plots the rate of total private hiring relative to employment (RHP). The rate collapsed during the global recession after 2007 with insufficient recovery.

Chart I-5A, US, Rate Total Private Hiring Level, Annual, 2001-2012

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Total nonfarm hiring (HNF), total private hiring (HP) and their respective rates are provided for the month of Dec in the years from 2001 to 2013 in Table I-3. Hiring numbers are in thousands. There is moderate recovery in HNF from 2744 thousand (or 2.7 million) in Dec 2009 to 2948 thousand in Dec 2010, 2990 thousand in Dec 2011, 3013 thousand in Dec 2012 and 4169 thousand in Dec 2013 for cumulative gain of 15.5 percent. HP rose from 2600 thousand in Dec 2009 to 2782 thousand in Dec 2010, 2809 thousand in Dec 2011, 2842 thousand in Dec 2012 and 3005 thousand in Dec 2013 for cumulative gain of 15.6 percent. HNF has fallen from 3835 thousand in Dec 2006 to 3169 thousand in Dec 2013 or by 17.4 percent. HP has fallen from 3635 thousand in Dec 2006 to 3005 thousand in Dec 2013 or by 17.3 percent. The civilian noninstitutional population of the US, or individuals in condition to work, rose from 228.815 million in 2006 to 245.679 million in 2013 or by 16.864 million and the civilian labor force from 151.428 million in 2006 to 155.389 million in 2013 or by 3.961 million (http://www.bls.gov/data/). The number of nonfarm hires in the US fell from 63.773 million in 2006 to 51.991 million in 2012 or by 11.782 million and the number of private hires fell from 59.494 million in 2006 to 48.493 million in 2012 or by 11 million (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/). Private hiring of 63,773 million in 2006 was equivalent to 27.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 228.815, or those in condition of working, falling to 48.493 million in 2012 or 19.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 243.284 million in 2012. The percentage of hiring in civilian noninstitutional population of 27.9 percent in 2006 would correspond to 67.876 million of hiring in 2012, which would be 19.383 million higher than actual 48.493 million in 2012. Cyclical slow growth over the entire business cycle from IVQ2007 to the present in comparison with earlier cycles and long-term trend (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html) explains the fact that there are many million fewer hires in the US than before the global recession. The labor market continues to be fractured, failing to provide an opportunity to exit from unemployment/underemployment or to find an opportunity for advancement away from declining inflation-adjusted earnings.

Table I-3, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in

Thousands and in Percentage of Total Employment Not Seasonally Adjusted

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 Dec | 3541 | 2.7 | 3317 | 3.0 |

| 2002 Dec | 3698 | 2.8 | 3493 | 3.2 |

| 2003 Dec | 3697 | 2.8 | 3490 | 3.2 |

| 2004 Dec | 3859 | 2.9 | 3643 | 3.3 |

| 2005 Dec | 3777 | 2.8 | 3568 | 3.1 |

| 2006 Dec | 3835 | 2.8 | 3635 | 3.2 |

| 2007 Dec | 3610 | 2.6 | 3393 | 2.9 |

| 2008 Dec | 2997 | 2.2 | 2836 | 2.5 |

| 2009 Dec | 2744 | 2.1 | 2600 | 2.4 |

| 2010 Dec | 2948 | 2.2 | 2782 | 2.6 |

| 2011 Dec | 2990 | 2.2 | 2809 | 2.5 |

| 2012 Dec | 3013 | 2.2 | 2842 | 2.5 |

| 2013 Dec | 3169 | 2.3 | 3005 | 2.6 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/jlt/

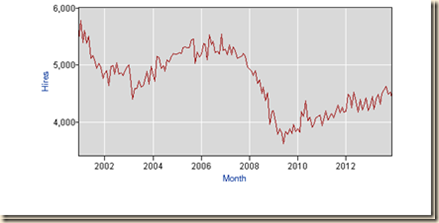

Chart I-6 provides total nonfarm hiring on a monthly basis from 2001 to 2013. Nonfarm hiring rebounded in early 2010 but then fell and stabilized at a lower level than the early peak not-seasonally adjusted (NSA) of 4774 in May 2010 until it surpassed it with 4883 in Jun 2011 but declined to 3013 in Dec 2012. Nonfarm hiring fell to 2990 in Dec 2011 from 3827 in Nov and to revised 3683 in Feb 2012, increasing to 4210 in Mar 2012, 3013 in Dec 2012 and 4128 in Jan 2013 and declining to 3661 in Feb 2013. Nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted increased to 4137 in Nov 2013 and 3169 in Dec 2013. Chart I-6 provides seasonally adjusted (SA) monthly data. The number of seasonally-adjusted hires in Oct 2011 was 4159 thousand, increasing to revised 4489 thousand in Feb 2012, or 7.9 percent, moving to 4195 in Dec 2012 for cumulative increase of 0.5 percent from 4174 in Dec 2011 and 4437 in Dec 2013 for increase of 5.8 percent relative to 4195 in Dec 2012. The number of hires not seasonally adjusted was 4883 in Jun 2011, falling to 2990 in Dec 2011 but increasing to 4013 in Jan 2012 and declining to 3013 in Dec 2012. The number of nonfarm hiring not seasonally adjusted fell by 38.8 percent from 4883 in Jun 2011 to 2990 in Dec 2011 and fell 41.3 percent from 5130 in Jun 2012 to 3013 in Dec 2012 in a yearly-repeated seasonal pattern. The number of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 5087 in Jun 2013 to 3169 in Dec 2013, or decline of 37.7 percent, showing strong seasonality.

Chart I-6, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), 2001-2013 Month SA

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

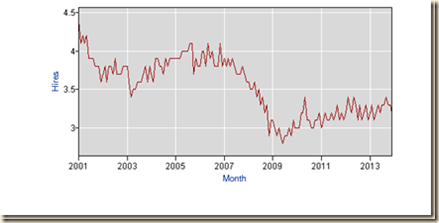

Similar behavior occurs in the rate of nonfarm hiring in Chart I-7. Recovery in early 2010 was followed by decline and stabilization at a lower level but with stability in monthly SA estimates of 3.2 in Aug 2011 to 3.2 in Jan 2012, increasing to 3.4 in May 2012 and falling to 3.3 in Jun 2012. The rate fell to 3.1 in Jul 2012, increasing to 3.3 in Aug 2012 but falling to 3.1 in Dec 2012 and 3.2 in Dec 2013. The rate not seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Jun 2011 to 2.2 in Dec 2011, climbing to 3.8 in Jun 2012 but falling to 2.2 in Dec 2012. The rate of nonfarm hires not seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Jun 2013 to 2.3 in Dec 2013. Rates of nonfarm hiring NSA were in the range of 2.8 (Dec) to 4.5 (Jun) in 2006.

Chart I-7, US, Rate Total Nonfarm Hiring, Month SA 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

There is only milder improvement in total private hiring shown in Chart I-8. Hiring private (HP) rose in 2010 with stability and renewed increase in 2011 followed by almost stationary series in 2012. The number of private hiring seasonally adjusted fell from 4026 thousand in Sep 2011 to 3876 in Dec 2011 or by 3.7 percent, decreasing to 3915 in Jan 2012 or decline by 2.8 percent relative to the level in Sep 2011. The rate fell to 3934 in Sep 2012 or lower by 2.3 percent relative to Sep 2011, decreasing to 3915 in Dec 2012 for change of 0.0 percent relative to 3915 in Jan 2012. The number of private hiring not seasonally adjusted fell from 4504 in Jun 2011 to 2809 in Dec 2011 or by 37.6 percent, reaching 3749 in Jan 2012 or decline of 16.8 percent relative to Jun 2011 and moving to 2842 in Dec 2012 or 39.8 percent lower relative to 4724 in Jun 2012. Hires fell from 4692 in Jun 2013 to 3005 in Dec 2013. Companies do not hire in the latter part of the year that explains the high seasonality in year-end employment data. For example, NSA private hiring fell from 5661 in Jun 2006 to 3635 in Dec 2006 or by 35.8 percent. Private hiring NSA data are useful in showing the huge declines from the period before the global recession. In Jul 2006, private hiring NSA was 5555, declining to 4245 in Jul 2011 or by 23.6 percent and to 4277 in Jul 2012 or lower by 23.0 percent relative to Jul 2006. Private hiring NSA fell from 3635 in Dec 2006 to 2842 in Dec 2012 or 21.8 percent and declined to 3005 in Dec 2013 or lower by 17.3 percent relative to Dec 2006. Private hiring fell from 5555 in Jul 2006 to 4633 in Jun 2013 or 16.6 percent. The conclusion is that private hiring in the US is around 20 percent below the hiring before the global recession while the noninstitutional population of the United States has grown from 228.815 million in 2006 to 245.679 million in 2013, by 16.864 million or 7.4 percent. The main problem in recovery of the US labor market has been the low rate of GDP growth. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent.

Chart I-8, US, Total Private Hiring Month SA 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-9 shows similar behavior in the rate of private hiring. The rate in 2011 in monthly SA data did not rise significantly above the peak in 2010. The rate seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Sep 2011 to 3.5 in Dec 2011 and reached 3.5 in Dec 2012 and 3.6 in Dec 2013. The rate not seasonally adjusted (NSA) fell from 3.7 in Sep 2011 to 2.5 in Dec 2011, increasing to 3.8 in Oct 2012 but falling to 2.5 in Dec 2012 and 3.4 in Mar 2013. The NSA rate of private hiring fell from 4.8 in Jul 2006 to 3.4 in Aug 2009 but recovery was insufficient to only 3.8 in Aug 2012, 2.5 in Dec 2012 and 2.6 in Dec 2013. The rate of private hires fell from 4.8 in Jul 2006 to 4.0 in Jul 2013. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Chart I-9, US, Rate Total Private Hiring Month SA 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The JOLTS report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics also provides total nonfarm job openings (TNF JOB), TNF JOB rate and TNF LD (layoffs and discharges) shown in Table I-4 for the month of Dec from 2001 to 2013. The final column provides annual TNF LD for the years from 2001 to 2012. Nonfarm job openings (TNF JOB) fell from a peak of 4036 in Dec 2006 to 3414 in Dec 2013 or by 15.4 percent while the rate dropped from 2.8 to 2.4. Nonfarm layoffs and discharges (TNF LD) rose from 1939 in Dec 2005 to 2782 in Dec 2008 or by 43.5 percent. The annual data show layoffs and discharges rising from 21.2 million in 2006 to 26.8 million in 2009 or by 26.4 percent. Business pruned payroll jobs to survive the global recession but there has not been hiring because of the low rate of GDP growth. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Table I-4, US, Total Nonfarm Job Openings and Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Thousands NSA

| TNF JOB | TNF JOB | TNF LD | TNF LD | |

| Dec 2001 | 3012 | 2.2 | 2030 | 24499 |

| Dec 2002 | 2629 | 2.0 | 2169 | 22922 |

| Dec 2003 | 2790 | 2.1 | 2186 | 23294 |

| Dec 2004 | 3312 | 2.4 | 2180 | 22802 |

| Dec 2005 | 3762 | 2.7 | 1939 | 22185 |

| Dec 2006 | 4036 | 2.8 | 1973 | 21157 |

| Dec 2007 | 3793 | 2.7 | 2012 | 22142 |

| Dec 2008 | 2649 | 1.9 | 2782 | 24181 |

| Dec 2009 | 2170 | 1.6 | 2296 | 26784 |

| Dec 2010 | 2569 | 1.9 | 2064 | 21773 |

| Dec 2011 | 2926 | 2.1 | 1910 | 20401 |

| Dec 2012 | 3103 | 2.2 | 1786 | 20546 |

| Dec 2013 | 3414 | 2.4 | 1802 |

Notes: TNF JOB: Total Nonfarm Job Openings; LD: Layoffs and Discharges

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/jlt/

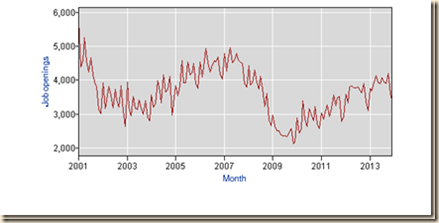

Chart I-10 shows monthly job openings rising from the trough in 2009 to a high in the beginning of 2010. Job openings then stabilized into 2011 but have surpassed the peak of 3142 seasonally adjusted in Apr 2010 with 3612 seasonally adjusted in Dec 2012, which is higher by 15.0 percent relative to Apr 2010 but lower by 4.7 percent relative to 3789 in Nov 2012 and lower by 6.1 percent than 3848 in Mar 2012. Nonfarm job openings increased from 3612 in Dec 2012 to 3990 in Dec 2013 or by 10.5 percent. The high of job openings not seasonally adjusted was 3396 in Apr 2010 that was surpassed by 3554 in Jul 2011, increasing to 3896 in Oct 2012 but declining to 3103 in Dec 2012 and decreasing to 3414 in Dec 2013. The level of job openings not seasonally adjusted fell to 3103 in Dec 2012 or by 19.0 percent relative to 3831 in Apr 2012. There is here again the strong seasonality of year-end labor data. Job openings fell from 4130 in Apr 2013 to 3414 in Dec 2013, showing strong seasonal effects. The level of job openings of 3414 in Dec 2013 NSA is lower by 15.4 percent relative to 4036 in Dec 2006. The main problem in recovery of the US labor market has been the low rate of GDP growth. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent.

Chart I-10, US Job Openings, Thousands NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

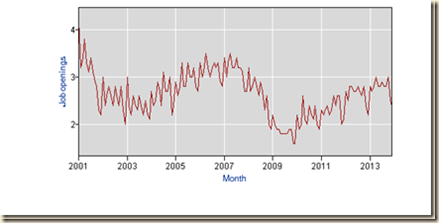

The rate of job openings in Chart I-11 shows similar behavior. The rate seasonally adjusted rose from 2.2 percent in Jan 2011 to 2.5 percent in Dec 2011, 2.6 in Dec 2012 and 2.8 in Dec 2013. The rate not seasonally adjusted rose from the high of 2.6 in Apr 2010 to 3.0 in Apr 2013 and 2.5 in Nov 2013. The rate of job openings NSA fell from 3.4 in Jul 2007 to 1.6 in Nov-Dec 2009, recovering insufficiently to 2.4 in Dec 2013. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Chart I-11, US, Rate of Job Openings, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

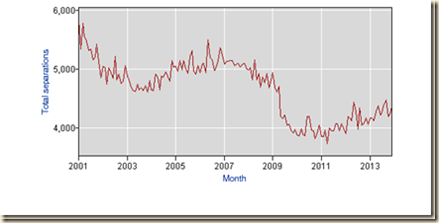

Total separations are shown in Chart I-12. Separations are much lower in 2012-13 than before the global recession but hiring has not recovered.

Chart I-12, US, Total Nonfarm Separations, Month Thousands SA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Annual total separations are shown in Chart I-13. Separations are much lower in 2011-2012 than before the global recession but without recovery in hiring.

Chart I-13, US, Total Separations, Annual, Thousands, 2001-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-5 provides total nonfarm total separations from 2001 to 2012. Separations fell from 61.6 million in 2006 to 47.6 million in 2010 or by 14.0 million and 47.6 million in 2011 or by 14.0 million. Total separations increased from 47.6 million in 2011 to 49.7 million in 2012 or by 2.1 million.

Table I-5, US, Total Nonfarm Total Separations, Thousands, 2001-2012

| Year | Annual |

| 2001 | 64765 |

| 2002 | 59190 |

| 2003 | 56487 |

| 2004 | 58340 |

| 2005 | 60733 |

| 2006 | 61565 |

| 2007 | 61162 |

| 2008 | 58627 |

| 2009 | 51532 |

| 2010 | 47646 |

| 2011 | 47626 |

| 2012 | 49676 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Monthly data of layoffs and discharges reach a peak in early 2009, as shown in Chart I-14. Layoffs and discharges dropped sharply with the recovery of the economy in 2010 and 2011 once employers reduced their job count to what was required for cost reductions and loss of business. Weak rates of growth of GDP (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html) frustrated employment recovery. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Chart I-14, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Monthly Thousands SA, 2011-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Layoffs and discharges in Chart I-15 rose sharply to a peak in 2009. There was pronounced drop into 2010 and 2011 with mild increase into 2012.

Chart I-15, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Annual, 2001-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-6 provides annual nonfarm layoffs and discharges from 2001 to 2012. Layoffs and discharges peaked at 26.8 million in 2009 and then fell to 20.4 million in 2011, by 6.4 million, or 23.9 percent. Total nonfarm layoffs and discharges increased mildly to 20.5 million in 2012.

Table I-6, US, Total Nonfarm Layoffs and Discharges, Thousands, 2001-2012

Year Annual

2001 24499

2002 22922

2003 23294

2004 22802

2005 22185

2006 21157

2007 22142

2008 24181

2009 26784

2010 21773

2011 20401

2012 20546

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

IA2 Labor Underutilization. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also provides alternative measures of labor underutilization shown in Table I-7. The most comprehensive measure is U6 that consists of total unemployed plus total employed part time for economic reasons plus all marginally attached workers as percent of the labor force. U6 not seasonally annualized has risen from 8.2 percent in 2006 to 13.5 percent in Jan 2014.

Table I-7, US, Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization NSA %

| U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | U5 | U6 | |

| 2014 | ||||||

| Jan | 3.5 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 13.5 |

| 2013 | ||||||

| Dec | 3.5 | 3.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 13.0 |

| Nov | 3.7 | 3.5 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 12.7 |

| Oct | 3.7 | 3.6 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 13.2 |

| Sep | 3.7 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 8.4 | 13.1 |

| Aug | 3.7 | 3.8 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 13.6 |

| Jul | 3.7 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 14.3 |

| Jun | 3.9 | 3.8 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 14.6 |

| May | 4.1 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 13.4 |

| Apr | 4.3 | 3.9 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 13.4 |

| Mar | 4.3 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 13.9 |

| Feb | 4.3 | 4.6 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 14.9 |

| Jan | 4.3 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 15.4 |

| 2012 | ||||||

| Dec | 4.2 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 14.4 |

| Nov | 4.2 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 13.9 |

| Oct | 4.3 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 13.9 |

| Sep | 4.2 | 4.0 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 14.2 |

| Aug | 4.3 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 14.6 |

| Jul | 4.3 | 4.6 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 15.2 |

| Jun | 4.5 | 4.4 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 9.9 | 15.1 |

| May | 4.7 | 4.3 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 14.3 |

| Apr | 4.8 | 4.3 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 14.1 |

| Mar | 4.9 | 4.8 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 14.8 |

| Feb | 4.9 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 15.6 |

| Jan | 4.9 | 5.4 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 10.5 | 16.2 |

| 2011 | ||||||

| Dec | 4.8 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 15.2 |

| Nov | 4.9 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 15.0 |

| Oct | 5.0 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 15.3 |

| Sep | 5.2 | 5.0 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 15.7 |

| Aug | 5.2 | 5.1 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 16.1 |

| Jul | 5.2 | 5.2 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 16.3 |

| Jun | 5.1 | 5.1 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 16.4 |

| May | 5.5 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 15.4 |

| Apr | 5.5 | 5.2 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 15.5 |

| Mar | 5.7 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 16.2 |

| Feb | 5.6 | 6.0 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 16.7 |

| Jan | 5.6 | 6.2 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 11.4 | 17.3 |

| Dec 2010 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 16.6 |

| Annual | ||||||

| 2013 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 13.8 |

| 2012 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.5 | 14.7 |

| 2011 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 15.9 |

| 2010 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 16.7 |

| 2009 | 4.7 | 5.9 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.5 | 16.2 |

| 2008 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 10.5 |

| 2007 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 8.3 |

| 2006 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 8.2 |

| 2005 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 8.9 |

| 2004 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 9.6 |

| 2003 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 10.1 |

| 2002 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 9.6 |

| 2001 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 8.1 |

| 2000 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 7.0 |

Note: LF: labor force; U1, persons unemployed 15 weeks % LF; U2, job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs %LF; U3, total unemployed % LF; U4, total unemployed plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers; % LF plus discouraged workers; U5, total unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers % LF plus all marginally attached workers; U6, total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons % LF plus all marginally attached workers

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Monthly seasonally adjusted measures of labor underutilization are provided in Table I-8. U6 climbed from 16.1 percent in Aug 2011 to 16.3 percent in Sep 2011 and then fell to 14.5 percent in Mar 2012, reaching 13.1 percent in Jan 2014. Unemployment is an incomplete measure of the stress in US job markets. A different calculation in this blog is provided by using the participation rate in the labor force before the global recession. This calculation shows 30.3 million in job stress of unemployment/underemployment in Dec 2013, not seasonally adjusted, corresponding to 18.5 percent of the labor force (Table I-4 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html).

Table I-8, US, Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization SA %

| U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | U5 | U6 | |

| Jan 2014 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 13.1 |

| Dec 2013 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 13.1 |

| Nov | 3.7 | 3.7 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 13.1 |

| Oct | 3.8 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 13.7 |

| Sep | 3.8 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 13.6 |

| Aug | 3.8 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 13.6 |

| Jul | 3.9 | 3.8 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 13.9 |

| Jun | 4.0 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 14.2 |

| May | 4.0 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 13.8 |

| Apr | 4.1 | 4.1 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 13.9 |

| Mar | 4.1 | 4.1 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 13.8 |

| Feb | 4.2 | 4.2 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 9.3 | 14.3 |

| Jan | 4.2 | 4.3 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 14.4 |

| Dec 2012 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 14.4 |

| Nov | 4.2 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 14.4 |

| Oct | 4.4 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 14.4 |

| Sep | 4.3 | 4.2 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 9.3 | 14.7 |

| Aug | 4.4 | 4.5 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 14.7 |

| Jul | 4.5 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 14.9 |

| Jun | 4.6 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 14.8 |

| May | 4.6 | 4.5 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 14.8 |

| Apr | 4.6 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.5 | 14.6 |

| Mar | 4.7 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 14.5 |

| Feb | 4.8 | 4.6 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 15.0 |

| Jan | 4.8 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 15.1 |

| Dec 2011 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 15.2 |

| Nov | 5.0 | 5.0 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 15.6 |

| Oct | 5.1 | 5.1 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 15.9 |

| Sep | 5.4 | 5.2 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 16.3 |

| Aug | 5.3 | 5.2 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 16.1 |

| Jul | 5.3 | 5.3 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 16.0 |

| Jun | 5.3 | 5.3 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 16.1 |

| May | 5.3 | 5.4 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.3 | 15.8 |

| Apr | 5.2 | 5.4 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 10.5 | 16.1 |

| Mar | 5.3 | 5.4 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 15.9 |

| Feb | 5.4 | 5.5 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 16.0 |

| Jan | 5.5 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 10.7 | 16.1 |

Note: LF: labor force; U1, persons unemployed 15 weeks % LF; U2, job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs %LF; U3, total unemployed % LF; U4, total unemployed plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers; % LF plus discouraged workers; U5, total unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers % LF plus all marginally attached workers; U6, total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons % LF plus all marginally attached workers

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

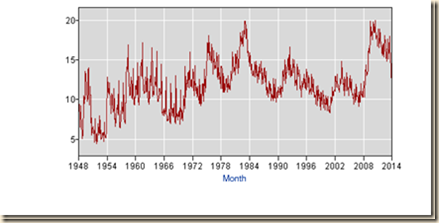

Chart I-16 provides U6 on a monthly basis from 2001 to 2014. There was a steep climb from 2007 into 2009 and then this measure of unemployment and underemployment stabilized at that high level but declined into 2012. The low of U6 SA was 8.0 percent in Mar 2007 and the peak was 17.1 percent in Apr 2010. The low NSA was 7.6 percent in Oct 2006 and the peak was 18.0 percent in Jan 2010.

Chart I-16, US, U6, total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed Part-Time for Economic Reasons, Month, SA, 2001-2014

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-17 provides the number employed part-time for economic reasons or who cannot find full-time employment. There are sharp declines at the end of 2009, 2010 and 2011 but an increase in 2012 followed by stability in 2013.

Chart I-17, US, Working Part-time for Economic Reasons

Thousands, Month SA 2001-2014

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

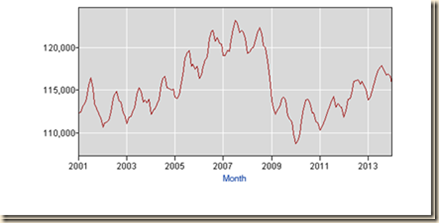

ICA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. There is strong seasonality in US labor markets around the end of the year. The number employed part-time for economic reasons because they could not find full-time employment fell from 9.068 million in Sep 2011 to 7.780 million in Mar 2012, seasonally adjusted, or decline of 1.288 million in six months, as shown in Table I-9. The number employed part-time for economic reasons rebounded to 8.572 million in Sep 2012 for increase of 527,000 in one month from Aug to Sep 2012. The number employed part-time for economic reasons declined to 8.231 million in Oct 2012 or by 341,000 again in one month, further declining to 8.164 million in Nov 2012 for another major one-month decline of 67,000 and 7.929 million in Dec 2012 or fewer 235,000 in just one month. The number employed part-time for economic reasons increased to 7.983 million in Jan 2013 or 54,000 more than in Dec 2012 and to 7,991 million in Feb 2013, declining to 7.917 million in May 2013 but increasing to 8.194 million in Jun 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons fell to 7.898 million in Aug 2013 for decline of 282,000 in one month from 8.180 million in Jul 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons increased 16,000 from 7.898 million in Aug 2013 to 7.914 million in Sep 2013. The number part-time for economic reasons rose to 8.016 million in Oct 2013, falling by 293,000 to 7.723 million in Nov 2013. The number part-time for economic reasons increased to 7.771 million in Dec 2013, decreasing to 7.257 million in Jan 2014. There is an increase of 186,000 in part-time for economic reasons from Aug 2012 to Oct 2012 and of 119,000 from Aug 2012 to Nov 2012. The number employed full-time increased from 112.906 million in Oct 2011 to 115.114 million in Mar 2012 or 2.208 million but then fell to 114.279 million in May 2012 or 0.835 million fewer full-time employed than in Mar 2012. The number employed full-time increased from 114.626 million in Aug 2012 to 115.531 million in Oct 2012 or increase of 0.905 million full-time jobs in two months and further to 115.821 million in Jan 2013 or increase of 1.195 million more full-time jobs in five months from Aug 2012 to Jan 2013. The number of full time jobs decreased slightly to 115.785 million in Feb 2013, increasing to 116.288 million in May 2013 and 116.087 million in Jun 2013. Then number of full-time jobs increased to 116.156 million in Jul 2013, 116.301 million in Aug 2013 and 116.883 million in Sep 2013. The number of full-time jobs fell to 116.306 million in Oct 2013 and increased to 116.951 in Nov 2013. The level of full-time jobs fell to 117.278 million in Dec 2013, increasing to 117.656 million in Jan 2014. Benchmark and seasonality-factors adjustments at the turn of every year could affect comparability of labor market indicators (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html). The number of employed part-time for economic reasons actually increased without seasonal adjustment from 8.271 million in Nov 2011 to 8.428 million in Dec 2011 or by 157,000 and then to 8.918 million in Jan 2012 or by an additional 490,000 for cumulative increase from Nov 2011 to Jan 2012 of 647,000. The level of employed part-time for economic reasons then fell from 8.918 million in Jan 2012 to 7.867 million in Mar 2012 or by 1.051 million and to 7.694 million in Apr 2012 or 1.224 million fewer relative to Jan 2012. In Aug 2012, the number employed part-time for economic reasons reached 7.842 million NSA or 148,000 more than in Apr 2012. The number employed part-time for economic reasons increased from 7.842 million in Aug 2012 to 8.110 million in Sep 2012 or by 3.4 percent. The number part-time for economic reasons fell from 8.110 million in Sep 2012 to 7.870 million in Oct 2012 or by 240.000 in one month. The number employed part-time for economic reasons NSA increased to 8.628 million in Jan 2013 or 758,000 more than in Oct 2012. The number employed part-time for economic reasons fell to 8.298 million in Feb 2013, which is lower by 330,000 relative to 8.628 million in Jan 2013 but higher by 428,000 relative to 7.870 million in Oct 2012. The number employed part time for economic reasons fell to 7.734 million in Mar 2013 or 564,000 less than in Feb 2013 and fell to 7.709 million in Apr 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons reached 7.618 million in May 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons jumped from 7.618 million in May 2013 to 8.440 million in Jun 2013 or 822,000 in one month. The number employed part-time for economic reasons fell to 8.324 million in Jul 2013 and 7.690 million in Aug 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons NSA fell to 7.522 million in Sep 2013, increasing to 7.700 million in Oct 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons fell to 7.563 million in Nov 2013 and increased to 7.990 million in Dec 2013. The number employed part-time for economic reasons fell to 7.771 million in Jan 2014. The number employed full time without seasonal adjustment fell from 113.138 million in Nov 2011 to 113.050 million in Dec 2011 or by 88,000 and fell further to 111.879 in Jan 2012 for cumulative decrease of 1.259 million. The number employed full-time not seasonally adjusted fell from 113.138 million in Nov 2011 to 112.587 million in Feb 2012 or by 551.000 but increased to 116.214 million in Aug 2012 or 3.076 million more full-time jobs than in Nov 2011. The number employed full-time not seasonally adjusted decreased from 116.214 million in Aug 2012 to 115.678 million in Sep 2012 for loss of 536,000 full-time jobs and rose to 116.045 million in Oct 2012 or by 367,000 full-time jobs in one month relative to Sep 2012. The number employed full-time NSA fell from 116.045 million in Oct 2012 to 115.515 million in Nov 2012 or decline of 530.000 in one month. The number employed full-time fell from 115.515 in Nov 2012 to 115.079 million in Dec 2012 or decline by 436,000 in one month. The number employed full time fell from 115.079 million in Dec 2012 to 113.868 million in Jan 2013 or decline of 1.211 million in one month. The number of full time jobs increased to 114.191 in Feb 2012 or by 323,000 in one month and increased to 114.796 million in Mar 2013 for cumulative increase from Jan by 928,000 full-time jobs but decrease of 283,000 from Dec 2012. The number employed full time reached 117.400 million in Jun 2013 and increased to 117.688 in Jul 2013 or by 288,000. The number employed full-time reached 117.868 million in Aug 2013 for increase of 180,000 in one month relative to Jul 2013. The number employed full-time fell to 117.308 million in Sep 2013 or by 560,000. The number employed full-time fell to 116.798 million in Oct 2013 or decline of 510.000 in one month. The number employed full-time rose to 116.875 million in Nov 2013, falling to 116.661 million in Dec 2013. The number employed full-time fell to 115.744 million in Jan 2014. Comparisons over long periods require use of NSA data. The number with full-time jobs fell from a high of 123.219 million in Jul 2007 to 108.777 million in Jan 2010 or by 14.442 million. The number with full-time jobs in Jan 2014 is 115.774 million, which is lower by 7.475 million relative to the peak of 123.219 million in Jul 2007. The magnitude of the stress in US labor markets is magnified by the increase in the civilian noninstitutional population of the United States from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 246.915 million in Jan 2014 or by 14.957 million (http://www.bls.gov/data/) while in the same period the number of full-time jobs fell 7.475 million. The ratio of full-time jobs of 123.219 million Jul 2007 to civilian noninstitutional population of 231.958 million was 53.1 percent. If that ratio had remained the same, there would be 131.112 million full-time jobs with population of 246.915 million in Jan 2014 or 15.368 million fewer full-time jobs relative to actual 115.744 million. There appear to be around 10 million fewer full-time jobs in the US than before the global recession while population increased around 14 million. Mediocre GDP growth is the main culprit of the fractured US labor market. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective underutilization rate of 18.5 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 30.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.5 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/financial-instability-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation.

Table I-9, US, Employed Part-time for Economic Reasons, Thousands, and Full-time, Millions

| Part-time Thousands | Full-time Millions | |

| Seasonally Adjusted | ||

| Jan 2014 | 7,257 | 117,656 |

| Dec 2013 | 7,771 | 117.278 |

| Nov 2013 | 7,723 | 116.951 |

| Oct 2013 | 8,016 | 116.306 |

| Sep 2013 | 7,914 | 116.883 |

| Aug 2013 | 7,898 | 116.301 |

| Jul 2013 | 8,180 | 116.156 |

| Jun 2013 | 8,194 | 116.087 |

| May 2013 | 7,917 | 116.288 |

| Apr 2013 | 7,929 | 116.062 |

| Mar 2013 | 7,663 | 115.901 |

| Feb 2013 | 7,991 | 115.785 |

| Jan 2013 | 7,983 | 115.821 |

| Dec 2012 | 7,929 | 115.735 |

| Nov 2012 | 8,164 | 115.581 |

| Oct 2012 | 8,231 | 115.531 |

| Sep 2012 | 8,572 | 115.229 |

| Aug 2012 | 8,045 | 114.626 |

| Jul 2012 | 8,163 | 114.589 |

| Jun 2012 | 8,154 | 114.728 |

| May 2012 | 8,138 | 114.279 |

| Apr 2012 | 7,913 | 114.398 |

| Mar 2012 | 7,780 | 115.114 |

| Feb 2012 | 8,133 | 114.210 |

| Jan 2012 | 8,228 | 113.790 |

| Dec 2011 | 8,177 | 113.740 |

| Nov 2011 | 8,457 | 113.158 |

| Oct 2011 | 8,675 | 112.906 |

| Sep 2011 | 9,068 | 112.523 |

| Aug 2011 | 8,820 | 112.643 |

| Jul 2011 | 8,342 | 112.209 |

| Not Seasonally Adjusted | ||

| Jan 2014 | 7,771 | 115.744 |

| Dec 2013 | 7,990 | 116.661 |

| Nov 2013 | 7,563 | 116.875 |

| Oct 2013 | 7,700 | 116.798 |

| Sep 2013 | 7,522 | 117.308 |

| Aug 2013 | 7,690 | 117.868 |

| Jul 2013 | 8,324 | 117.688 |

| Jun 2013 | 8,440 | 117.400 |

| May 2013 | 7,618 | 116.643 |

| Apr 2013 | 7,709 | 115.674 |

| Mar 2013 | 7,734 | 114.796 |

| Feb 2013 | 8,298 | 114.191 |

| Jan 2013 | 8,628 | 113.868 |

| Dec 2012 | 8,166 | 115.079 |

| Nov 2012 | 7,994 | 115.515 |

| Oct 2012 | 7,870 | 116.045 |

| Sep 2012 | 8,110 | 115.678 |

| Aug 2012 | 7,842 | 116.214 |

| Jul 2012 | 8,316 | 116.131 |

| Jun 2012 | 8,394 | 116.024 |

| May 2012 | 7,837 | 114.634 |

| Apr 2012 | 7,694 | 113.999 |

| Mar 2012 | 7,867 | 113.916 |

| Feb 2012 | 8,455 | 112.587 |

| Jan 2012 | 8,918 | 111.879 |

| Dec 2011 | 8,428 | 113.050 |

| Nov 2011 | 8,271 | 113.138 |

| Oct 2011 | 8,258 | 113.456 |

| Sep 2011 | 8,541 | 112.980 |

| Aug 2011 | 8,604 | 114.286 |

| Jul 2011 | 8,514 | 113.759 |

| Jun 2011 | 8,738 | 113.255 |

| May 2011 | 8,270 | 112.618 |

| Apr 2011 | 8,425 | 111.844 |

| Mar 2011 | 8,737 | 111.186 |

| Feb 2011 | 8,749 | 110.731 |

| Jan 2011 | 9,187 | 110.373 |

| Dec 2010 | 9,205 | 111.207 |

| Nov 2010 | 8,670 | 111.348 |

| Oct 2010 | 8,408 | 112.342 |

| Sep 2010 | 8,628 | 112.385 |

| Aug 2010 | 8,628 | 113.508 |

| Jul 2010 | 8,737 | 113.974 |

| Jun 2010 | 8,867 | 113.856 |

| May 2010 | 8,513 | 112.809 |

| Apr 2010 | 8,921 | 111.391 |

| Mar 2010 | 9,343 | 109.877 |

| Feb 2010 | 9,282 | 109.100 |

| Jan 2010 | 9,290 | 108.777 (low) |

| Dec 2009 | 9,354 (high) | 109.875 |

| Nov 2009 | 8,894 | 111.274 |

| Oct 2009 | 8,474 | 111.599 |

| Sep 2009 | 8,255 | 111.991 |

| Aug 2009 | 8,835 | 113.863 |

| Jul 2009 | 9,103 | 114.184 |

| Jun 2009 | 9,301 | 114.014 |

| May 2009 | 8,785 | 113.083 |

| Apr 2009 | 8,648 | 112.746 |

| Mar 2009 | 9,305 | 112.215 |

| Feb 2009 | 9,170 | 112.947 |

| Jan 2009 | 8,829 | 113.815 |

| Dec 2008 | 8,250 | 116.422 |

| Nov 2008 | 7,135 | 118.432 |

| Oct 2008 | 6,267 | 120.020 |

| Sep 2008 | 5,701 | 120.213 |

| Aug 2008 | 5,736 | 121.556 |

| Jul 2008 | 6,054 | 122.378 |

| Jun 2008 | 5,697 | 121.845 |

| May 2008 | 5,096 | 120.809 |

| Apr 2008 | 5,071 | 120.027 |

| Mar 2008 | 5,038 | 119.875 |

| Feb 2008 | 5,114 | 119.452 |

| Jan 2008 | 5,340 | 119.332 |

| Dec 2007 | 4,750 | 121.042 |

| Nov 2007 | 4,374 | 121.846 |

| Oct 2007 | 4,028 | 122.006 |

| Sep 2007 | 4,137 | 121.728 |

| Aug 2007 | 4,494 | 122.870 |

| Jul 2007 | 4,516 | 123.219 (high) |

| Jun 2007 | 4,469 | 122.150 |

| May 2007 | 4,315 | 120.846 |

| Apr 2007 | 4,205 | 119.609 |

| Mar 2007 | 4,384 | 119.640 |

| Feb 2007 | 4,417 | 119.041 |

| Jan 2007 | 4,726 | 119.094 |

| Dec 2006 | 4,281 | 120.371 |

| Nov 2006 | 4,054 | 120.507 |

| Oct 2006 | 4,010 | 121.199 |

| Sep 2006 | 3,735 (low) | 120.780 |

| Aug 2006 | 4,104 | 121.979 |

| Jul 2006 | 4,450 | 121.951 |

| Jun 2006 | 4,456 | 121.070 |

| May 2006 | 3,968 | 118.925 |

| Apr 2006 | 3,787 | 118.559 |

| Mar 2006 | 4,097 | 117.693 |

| Feb 2006 | 4,403 | 116.823 |

| Jan 2006 | 4,597 | 116.395 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

People lose their marketable job skills after prolonged unemployment and face increasing difficulty in finding another job. Chart I-18 shows the sharp rise in unemployed over 27 weeks and stabilization at an extremely high level.

Chart I-18, US, Number Unemployed for 27 Weeks or Over, Thousands SA Month 2001-2014

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Another segment of U6 consists of people marginally attached to the labor force who continue to seek employment but less frequently on the frustration there may not be a job for them. Chart I-19 shows the sharp rise in people marginally attached to the labor force after 2007 and subsequent stabilization.

Chart I-19, US, Marginally Attached to the Labor Force, NSA Month, Thousands, 2001-2014

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

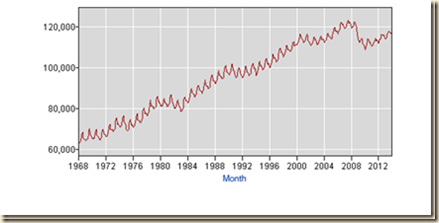

The number of workers with full-time jobs not-seasonally-adjusted rose with fluctuations from 2002 to a peak in 2007, collapsing during the global recession, as shown in Chart I-20. The magnitude of the stress in US labor markets is magnified by the increase in the civilian noninstitutional population of the United States from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 246.915 million in Jan 2014 or by 14.957 million (http://www.bls.gov/data/) while in the same period the number of full-time jobs fell 7.475 million. The ratio of full-time jobs of 123.219 million Jul 2007 to civilian noninstitutional population of 231.958 million was 53.1 percent. If that ratio had remained the same, there would be 131.112 million full-time jobs with population of 246.915 million in Jan 2014 or 15.368 million fewer full-time jobs relative to actual 115.744 million. There appear to be around 10 million fewer full-time jobs in the US than before the global recession while population increased around 14 million. There is current interest in past theories of “secular stagnation.” Alvin H. Hansen (1939, 4, 7; see Hansen 1938, 1941; for an early critique see Simons 1942) argues: