Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars Below Trend, Financial Turmoil, Stagnating Real Disposable Income, United States Housing Collapse, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Executive Summary

I Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars Below Trend

IA Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IB Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

II United States Housing Collapse

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

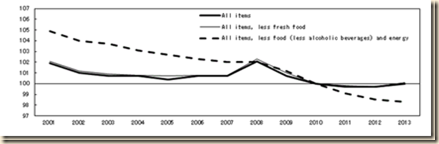

IV Global Inflation. There is inflation everywhere in the world economy, with slow growth and persistently high unemployment in advanced economies. Table IV-1, updated with every blog comment, provides the latest annual data for GDP, consumer price index (CPI) inflation, producer price index (PPI) inflation and unemployment (UNE) for the advanced economies, China and the highly indebted European countries with sovereign risk issues. The table now includes the Netherlands and Finland that with Germany make up the set of northern countries in the euro zone that hold key votes in the enhancement of the mechanism for solution of sovereign risk issues (Peter Spiegel and Quentin Peel, “Europe: Northern Exposures,” Financial Times, Mar 9, 2011 http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/55eaf350-4a8b-11e0-82ab-00144feab49a.html#axzz1gAlaswcW). Newly available data on inflation is considered below in this section. Data in Table IV-1 for the euro zone and its members are updated from information provided by Eurostat but individual country information is provided in this section as soon as available, following Table IV-1. Data for other countries in Table IV-1 are also updated with reports from their statistical agencies. Economic data for major regions and countries is considered in Section V World Economic Slowdown following with individual country and regional data tables.

Table IV-1, GDP Growth, Inflation and Unemployment in Selected Countries, Percentage Annual Rates

| GDP | CPI | PPI | UNE | |

| US | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 7.0 |

| Japan | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| China | 7.7 | 2.5 | -1.4 | |

| UK | 2.8 | 2.0* CPIH 1.9 | 1.0 output | 7.1 |

| Euro Zone | -0.3 | 0.8 | -1.2 | 12.0 |

| Germany | 0.6 | 1.2 | -0.7 | 5.1 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.8 | -0.6 | 10.8 |

| Nether-lands | -0.6 | 1.4 | -3.4 | 7.0 |

| Finland | -1.0 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 8.4 |

| Belgium | 0.4 | 1.2 | -2.7 | 8.4 |

| Portugal | -1.0 | 0.2 | -0.9 | 15.4 |

| Ireland | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 12.1 |

| Italy | -1.8 | 0.7 | -2.3 | 12.7 |

| Greece | -3.0 | -1.8 | -0.4 | 27.8 |

| Spain | -1.1 | 0.3 | -0.6 | 25.8 |

Notes: GDP: rate of growth of GDP; CPI: change in consumer price inflation; PPI: producer price inflation; UNE: rate of unemployment; all rates relative to year earlier

*Office for National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/cpi/consumer-price-indices/december-2013/index.html **Core

PPI http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ppi2/producer-price-index/december-2013/index.html

Source: EUROSTAT http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/eurostat/home/; country statistical sources http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

Table IV-1 shows the simultaneous occurrence of low growth, inflation and unemployment in advanced economies. The US grew at 2.7 percent in IVQ2013 relative to IVQ2012 (Section I and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html, Table 8 in http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp4q13_adv.pdf ). Japan’s GDP grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 relative to IIQ2013 and 2.4 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s grew at the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 1.1 percent in IIIQQ2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-unwinding-monetary-policy.html). The UK grew at 0.8 percent in IVQ2013 relative to IIIQ2013 and GDP increased 2.8 percent in IVQ2013 relative to IVQ2012 (Section VH and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/exit-risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html). The Euro Zone grew at 0.1 percent in IIIQ2013 and minus 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 relative to IIIQ2012 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html). These are stagnating or “growth recession” rates, which are positive or about nil growth rates with some contractions that are insufficient to recover employment. The rates of unemployment are quite high: 7.0 percent in the US but 18.0 percent for unemployment/underemployment or job stress of 29.3 million (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html), 3.7 percent for Japan (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/exit-risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html), 7.1 percent for the UK with high rates of unemployment for young people (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). Twelve-month rates of inflation have been quite high, even when some are moderating at the margin: 1.5 percent in the US, 1.6 percent for Japan, 2.5 percent for China, 0.8 percent for the Euro Zone and 2.0 percent for the UK. Stagflation is still an unknown event but the risk is sufficiently high to be worthy of consideration (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/risk-aversion-and-stagflation.html). The analysis of stagflation also permits the identification of important policy issues in solving vulnerabilities that have high impact on global financial risks. Six key interrelated vulnerabilities in the world economy have been causing global financial turbulence. (1) Sovereign risk issues in Europe resulting from countries in need of fiscal consolidation and enhancement of their sovereign risk ratings (see Section III and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html). (2) The tradeoff of growth and inflation in China now with change in growth strategy to domestic consumption instead of investment, high debt and political developments in a decennial transition. (3) Slow growth by repression of savings with de facto interest rate controls (Section IB and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html), weak hiring with the loss of 10 million full-time jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/capital-flows-exchange-rates-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html) and continuing job stress of 24 to 30 million people in the US and stagnant wages in a fractured job market (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html). (4) The timing, dose, impact and instruments of normalizing monetary and fiscal policies (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/08/expanding-bank-cash-and-deposits-with.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/united-states-gdp-growth-standstill.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/global-financial-risks-and-fed.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/policy-inflation-growth-unemployment.html) in advanced and emerging economies. (5) The Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011 had repercussions throughout the world economy. Japan has share of about 9 percent in world output, role as entry point for business in Asia, key supplier of advanced components and other inputs as well as major role in finance and multiple economic activities (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704461304576216950927404360.html?mod=WSJ_business_AsiaNewsBucket&mg=reno-wsj); and (6) geopolitical events in the Middle East.

In the effort to increase transparency, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) provides both economic projections of its participants and views on future paths of the policy rate that in the US is the federal funds rate or interest on interbank lending of reserves deposited at Federal Reserve Banks. These policies and views are discussed initially followed with appropriate analysis.

Charles Evans, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, proposed an “economic state-contingent policy” or “7/3” approach (Evans 2012 Aug 27):

“I think the best way to provide forward guidance is by tying our policy actions to explicit measures of economic performance. There are many ways of doing this, including setting a target for the level of nominal GDP. But recognizing the difficult nature of that policy approach, I have a more modest proposal: I think the Fed should make it clear that the federal funds rate will not be increased until the unemployment rate falls below 7 percent. Knowing that rates would stay low until significant progress is made in reducing unemployment would reassure markets and the public that the Fed would not prematurely reduce its accommodation.

Based on the work I have seen, I do not expect that such policy would lead to a major problem with inflation. But I recognize that there is a chance that the models and other analysis supporting this approach could be wrong. Accordingly, I believe that the commitment to low rates should be dropped if the outlook for inflation over the medium term rises above 3 percent.

The economic conditionality in this 7/3 threshold policy would clarify our forward policy intentions greatly and provide a more meaningful guide on how long the federal funds rate will remain low. In addition, I would indicate that clear and steady progress toward stronger growth is essential.”

Evans (2012Nov27) modified the “7/3” approach to a “6.5/2.5” approach:

“I have reassessed my previous 7/3 proposal. I now think a threshold of 6-1/2 percent for the unemployment rate and an inflation safeguard of 2-1/2 percent, measured in terms of the outlook for total PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index) inflation over the next two to three years, would be appropriate.”

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided at its meeting on Dec 12, 2012 to implement the “6.5/2.5” approach (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20121212a.htm):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

Another rising risk is division within the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on risks and benefits of current policies as expressed in the minutes of the meeting held on Jan 29-30, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20130130.pdf 13):

“However, many participants also expressed some concerns about potential costs and risks arising from further asset purchases. Several participants discussed the possible complications that additional purchases could cause for the eventual withdrawal of policy accommodation, a few mentioned the prospect of inflationary risks, and some noted that further asset purchases could foster market behavior that could undermine financial stability. Several participants noted that a very large portfolio of long-duration assets would, under certain circumstances, expose the Federal Reserve to significant capital losses when these holdings were unwound, but others pointed to offsetting factors and one noted that losses would not impede the effective operation of monetary policy.”

Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Fed maps exit from stimulus,” on May 11, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324744104578475273101471896.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection), analyzes the development of strategy for unwinding quantitative easing and how it can create uncertainty in financial markets. Jon Hilsenrath and Victoria McGrane, writing on “Fed slip over how long to keep cash spigot open,” published on Feb 20, 2013 in the Wall street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323511804578298121033876536.html), analyze the minutes of the Fed, comments by members of the FOMC and data showing increase in holdings of riskier debt by investors, record issuance of junk bonds, mortgage securities and corporate loans. Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Jobs upturn isn’t enough to satisfy Fed,” on Mar 8, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324582804578348293647760204.html), finds that much stronger labor market conditions are required for the Fed to end quantitative easing. Unconventional monetary policy with zero interest rates and quantitative easing is quite difficult to unwind because of the adverse effects of raising interest rates on valuations of risk financial assets and home prices, including the very own valuation of the securities held outright in the Fed balance sheet. Gradual unwinding of 1 percent fed funds rates from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004 by seventeen consecutive increases of 25 percentage points from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006 to reach 5.25 percent caused default of subprime mortgages and adjustable-rate mortgages linked to the overnight fed funds rate. The zero interest rate has penalized liquidity and increased risks by inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to speculative positions in risk financial assets. There is no exit from zero interest rates without provoking another financial crash.

Unconventional monetary policy will remain in perpetuity, or QE→∞, changing to a “growth mandate.” There are two reasons explaining unconventional monetary policy of QE→∞: insufficiency of job creation to reduce unemployment/underemployment at current rates of job creation; and growth of GDP at around 2.3 percent, which is well below 3.0 percent estimated by Lucas (2011May) from 1870 to 2010. Unconventional monetary policy interprets the dual mandate of low inflation and maximum employment as mainly a “growth mandate” of forcing economic growth in the US at a rate that generates full employment. A hurdle to this “growth mandate” is that US economic growth has been at only 2.4 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 18 quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2013. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IVQ2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,738.0 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,356.9 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,738.0/$14,356.9 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html). As a result, there are 29.3 million unemployed or underemployed in the United States for an effective unemployment rate of 18.0 percent (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html). The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion higher than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 29.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.0 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline.

First, total nonfarm payroll employment seasonally adjusted (SA) increased 74,000 in Dec 2013 and private payroll employment rose 87,000. The average number of nonfarm jobs created in Jan-Dec 2012 was 182,750, using seasonally adjusted data, while the average number of nonfarm jobs created in Jan-Dec 2013 was 182,167, or decrease by 0.3 percent. The average number of private jobs created in the US in Jan-Dec 2012 was 189,083, using seasonally adjusted data, while the average in Jan-Dec 2013 was 184,250, or decrease by 2.6 percent. This blog calculates the effective labor force of the US at 161.760 million in Dec 2012 and 163.345 million in Dec 2013 (Table I-4), for growth of 1.585 million at average 132,083 per month. The difference between the average increase of 182,167 new private nonfarm jobs per month in the US from Jan to Dec 2013 and the 132,083 average monthly increase in the labor force from is 50,084 monthly new jobs net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force. There are 29.3 million in job stress in the US currently. Creation of 50,084 new jobs per month net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force would require 586 months to provide jobs for the unemployed and underemployed (29.338 million divided by 50,084) or 49 years (586 divided by 12). The civilian labor force of the US in Dec 2013 not seasonally adjusted stood at 154.408 million with 9.984 million unemployed or effectively 18.921 million unemployed in this blog’s calculation by inferring those who are not searching because they believe there is no job for them for effective labor force of 163.345 million. Reduction of one million unemployed at the current rate of job creation without adding more unemployment requires 1.7 years (1 million divided by product of 50,084 by 12, which is 601,008). Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would be equivalent to unemployment of only 7.720 million (0.05 times labor force of 154.408 million) for new net job creation of 2.264 million (9.984 million unemployed minus 7.720 million unemployed at rate of 5 percent) that at the current rate would take 3.8 years (2.264 million divided by 0.601008). Under the calculation in this blog, there are 18.921 million unemployed by including those who ceased searching because they believe there is no job for them and effective labor force of 163.345 million. Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would require creating 10.164 million jobs net of labor force growth that at the current rate would take 17.9 years (18.921 million minus 0.05(163.345 million) = 10.754 million divided by 0.601008, using LF PART 66.2% and Total UEM in Table I-4). These calculations assume that there are no more recessions, defying United States economic history with periodic contractions of economic activity when unemployment increases sharply. The number employed in Dec 2013 was 144.423 million (NSA) or 2.892 million fewer people with jobs relative to the peak of 147.315 million in Jul 2007 while the civilian noninstitutional population increased from 231.958 million in Jul 2007 to 246.745 million in Dec 2013 or by 14.787 million. The number employed fell 2.0 percent from Jul 2007 to Dec 2013 while population increased 6.4 percent. There is actually not sufficient job creation in merely absorbing new entrants in the labor force because of those dropping from job searches, worsening the stock of unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs.

There is current interest in past theories of “secular stagnation.” Alvin H. Hansen (1939, 4, 7; see Hansen 1938, 1941; for an early critique see Simons 1942) argues:

“Not until the problem of full employment of our productive resources from the long-run, secular standpoint was upon us, were we compelled to give serious consideration to those factors and forces in our economy which tend to make business recoveries weak and anaemic (sic) and which tend to prolong and deepen the course of depressions. This is the essence of secular stagnation-sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions which feed on them-selves and leave a hard and seemingly immovable core of unemployment. Now the rate of population growth must necessarily play an important role in determining the character of the output; in other words, the com-position of the flow of final goods. Thus a rapidly growing population will demand a much larger per capita volume of new residential building construction than will a stationary population. A stationary population with its larger proportion of old people may perhaps demand more personal services; and the composition of consumer demand will have an important influence on the quantity of capital required. The demand for housing calls for large capital outlays, while the demand for personal services can be met without making large investment expenditures. It is therefore not unlikely that a shift from a rapidly growing population to a stationary or declining one may so alter the composition of the final flow of consumption goods that the ratio of capital to output as a whole will tend to decline.”

The argument that anemic population growth causes “secular stagnation” in the US (Hansen 1938, 1939, 1941) is as misplaced currently as in the late 1930s (for early dissent see Simons 1942). There is currently population growth in the ages of 16 to 24 years but not enough job creation and discouragement of job searches for all ages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html).

Second, US GDP grew 6.5 percent from $14,996.1 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $15,965.6 billion in IVQ2013 or 6.5 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth under trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IV2013 would have accumulated to 20.3 percent. GDP in IVQ2013 would be $18,040.3 billion if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,074.7 billion higher than actual $15,965.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than under trend, explaining the 29.3 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 18.0 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The economy of the US can be summarized in growth of economic activity or GDP as decelerating from mediocre growth of 2.5 percent on an annual basis in 2010 to 1.8 percent in 2011 to 2.8 percent in 2012. The following calculations show that actual growth is around 2.3 to 2.7 percent per year. This rate is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which the economy of the US always attained for entire cycles in expansions after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May). Revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) provide important information on long-term growth and cyclical behavior. Table Summary provides relevant data.

- Long-term. US GDP grew at the average yearly rate of 3.3 percent from 1929 to 2013 and at 3.2 percent from 1947 to 2013. There were periodic contractions or recessions in this period but the economy grew at faster rates in the subsequent expansions, maintaining long-term economic growth at trend.

- Cycles. The combined contraction of GDP in the two almost consecutive recessions in the early 1980s is 4.7 percent. The contraction of US GDP from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 during the global recession was 4.3 percent. The critical difference in the expansion is growth at average 7.8 percent in annual equivalent in the first four quarters of recovery from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The average rate of growth of GDP in four cyclical expansions in the postwar period is 7.7 percent. In contrast, the rate of growth in the first four quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 was only 2.7 percent. Average annual equivalent growth in the expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was 5.4 percent and 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987. In contrast, average annual equivalent growth in the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2013 was only 2.4 percent. The US appears to have lost its dynamism of income growth and employment creation.

Table Summary, Long-term and Cyclical Growth of GDP, Real Disposable Income and Real Disposable Income per Capita

| GDP | ||

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2013 | 3.3 | |

| 1947-2013 | 3.2 | |

| Cyclical Contractions ∆% | ||

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980, IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | -4.7 | |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | -4.3 | |

| Cyclical Expansions Average Annual Equivalent ∆% | ||

| IQ1983 to IVQ1985 IQ1983-IQ1986 IQ1983-IIIQ1986 IQ1983-IVQ1986 IQ1983-IQ1987 IQ1983-IIQ1987 | 5.9 5.7 5.4 5.2 5.0 5.0 | |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 7.8 | |

| IIIQ2009 to IVQ2013 | 2.4 | |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 | |

| Real Disposable Income | Real Disposable Income per Capita | |

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2013 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| 1947-1999 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| Whole Cycles | ||

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| 2006-2013 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) also provide critical information in assessing the current rhythm of US economic growth. The economy appears to be moving at a pace from 2.0 to 2.6 percent per year. Table Summary GDP provides the data.

1. Average Annual Growth in the Past Eight Quarters. GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012 and the four quarters of 2013 accumulated to 4.7 percent. This growth is equivalent to 2.3 percent per year, obtained by dividing GDP in IVQ2013 of $15,965.6 billion by GDP in IVQ2011 of $15,242.1 billion and compounding by 4/8: {[($15,965.6/$15,242.1)4/8 -1]100 = 2.3 percent.

2. Average Annual Growth in the Four Quarters of 2013. GDP growth in the first three quarters of 2013 accumulated to 1.9 percent that is equivalent to 2.7 percent in a year. This is obtained by dividing GDP in IVQ2013 of $15,965.6 billion by GDP in IVQ2012 of $15,539.6 billion and compounding by 4/4: {[($15,965.6/$15,539.6)4/4 -1]100 = 2.7%}. The US economy grew 2.7 percent in IVQ2013 relative to the same quarter a year earlier in IIIQ2012. Another important revelation of the revisions and enhancements is that GDP was flat in IVQ2012, which is just at the borderline of contraction. The rate of growth of GDP in the third estimate of IIIQ2013 is 4.1 percent in seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR). Inventory accumulation contributed 1.67 percentage points to this rate of growth. The actual rate without this impulse of unsold inventories would have been 2.43 percent, or 0.6 percent in IIIQ2013, such that annual equivalent growth in 2013 is closer to 2.0 percent {[(1.003)(1.006)(1.006)(1.0084/4-1]100 = 2.3%}, compounding the quarterly rates and converting into annual equivalent.

Table Summary GDP, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2009 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 14,996.1 | NA | NA | 1.9 |

| IVQ2011 | 15,242.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| IQ2012 | 15,381.6 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| IIQ2012 | 15,427.7 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| IIIQ2012 | 15,534.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| IVQ2012 | 15,539.6 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| IQ2013 | 15,583.9 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| IIQ2013 | 15,679.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| IIIQ2013 | 15,839.3 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| IVQ2013 | 15,965.6 | 6.5 | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| Cumulative ∆% IQ2012 to IVQ2013 | 4.7 | 4.7 | ||

| Annual Equivalent ∆% | 2.3 | 2.3 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

In fact, it is evident to the public that this policy will be abandoned if inflation costs rise. There is concern of the production and employment costs of controlling future inflation. Even if there is no inflation, QE→∞ cannot be abandoned because of the fear of rising interest rates. The economy would operate in an inferior allocation of resources and suboptimal growth path, or interior point of the production possibilities frontier where the optimum of productive efficiency and wellbeing is attained, because of the distortion of risk/return decisions caused by perpetual financial repression. Not even a second-best allocation is feasible with the shocks to efficiency of financial repression in perpetuity.

The statement of the FOMC at the conclusion of its meeting on Dec 12, 2012, revealed policy intentions (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20121212a.htm) practically unchanged in the statement at its meeting on Jan 29, 2014 with symbolic reduction of purchases of securities for the Fed’s balance sheet (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20140129a.htm):

“Release Date: January 29, 2014

For immediate release

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in December indicates that growth in economic activity picked up in recent quarters. Labor market indicators were mixed but on balance showed further improvement. The unemployment rate declined but remains elevated. Household spending and business fixed investment advanced more quickly in recent months, while the recovery in the housing sector slowed somewhat. Fiscal policy is restraining economic growth, although the extent of restraint is diminishing. Inflation has been running below the Committee's longer-run objective, but longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee expects that, with appropriate policy accommodation, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace and the unemployment rate will gradually decline toward levels the Committee judges consistent with its dual mandate. The Committee sees the risks to the outlook for the economy and the labor market as having become more nearly balanced. The Committee recognizes that inflation persistently below its 2 percent objective could pose risks to economic performance, and it is monitoring inflation developments carefully for evidence that inflation will move back toward its objective over the medium term.

Taking into account the extent of federal fiscal retrenchment since the inception of its current asset purchase program, the Committee continues to see the improvement in economic activity and labor market conditions over that period as consistent with growing underlying strength in the broader economy. In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions, the Committee decided to make a further measured reduction in the pace of its asset purchases. Beginning in February, the Committee will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $30 billion per month rather than $35 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $35 billion per month rather than $40 billion per month. The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. The Committee's sizable and still-increasing holdings of longer-term securities should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative, which in turn should promote a stronger economic recovery and help to ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with the Committee's dual mandate.

The Committee will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments in coming months and will continue its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate, until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. If incoming information broadly supports the Committee's expectation of ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and inflation moving back toward its longer-run objective, the Committee will likely reduce the pace of asset purchases in further measured steps at future meetings. However, asset purchases are not on a preset course, and the Committee's decisions about their pace will remain contingent on the Committee's outlook for the labor market and inflation as well as its assessment of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases.

To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. The Committee also reaffirmed its expectation that the current exceptionally low target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored. In determining how long to maintain a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy, the Committee will also consider other information, including additional measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal. When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; William C. Dudley, Vice Chairman; Richard W. Fisher; Narayana Kocherlakota; Sandra Pianalto; Charles I. Plosser; Jerome H. Powell; Jeremy C. Stein; Daniel K. Tarullo; and Janet L. Yellen.”

There are several important issues in this statement.

- Mandate. The FOMC pursues a policy of attaining its “dual mandate” of (http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm):

“Conducting the nation's monetary policy by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”

- Open-ended Quantitative Easing or QE∞ with Symbolic Tapering. Earlier programs are continued with an additional lower open-ended $75 billion of bond purchases per month, increasing the stock of $3,830,311 million securities held outright and bank reserves deposited at the Fed of $2,525,773 million (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1): “Taking into account the extent of federal fiscal retrenchment since the inception of its current asset purchase program, the Committee continues to see the improvement in economic activity and labor market conditions over that period as consistent with growing underlying strength in the broader economy. In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions, the Committee decided to make a further measured reduction in the pace of its asset purchases. Beginning in February, the Committee will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $30 billion per month rather than $35 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $35 billion per month rather than $40 billion per month. The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. The Committee's sizable and still-increasing holdings of longer-term securities should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative, which in turn should promote a stronger economic recovery and help to ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with the Committee's dual mandate.”

- Advance Guidance on “6 ¼ 2 ½ “Rule.” Policy will be accommodative even after the economy recovers satisfactorily: “To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. The Committee also reaffirmed its expectation that the current exceptionally low target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

- No Present Course of Policy Accommodation. Market participants focused on slightly different wording about asset purchases: “In determining how long to maintain a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy, the Committee will also consider other information, including additional measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal. When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent.”

- Growth. “The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal.”

Current focus is on tapering quantitative easing by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). There is sharp distinction between the two measures of unconventional monetary policy: (1) fixing of the overnight rate of fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent; and (2) outright purchase of Treasury and agency securities and mortgage-backed securities for the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. Market are overreacting to the so-called “paring” of outright purchases to $75 billion of securities per month for the balance sheet of the Fed. What is truly important is the fixing of the overnight fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent for which there is no end in sight as evident in the FOMC statement for Jan 29, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20140129a.htm ):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. The Committee also reaffirmed its expectation that the current exceptionally low target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored. The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal. (emphasis added).

There is a critical phrase in the statement of Sep 19, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130918a.htm): “but mortgage rates have risen further.” Did the increase of mortgage rates influence the decision of the FOMC not to taper? Is FOMC “communication” and “guidance” successful? Will the FOMC increase purchases of mortgage-backed securities if mortgage rates increase?

At the confirmation hearing on nomination for Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Vice Chair Yellen (2013Nov14 http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20131114a.htm), states needs and intentions of policy:

“We have made good progress, but we have farther to go to regain the ground lost in the crisis and the recession. Unemployment is down from a peak of 10 percent, but at 7.3 percent in October, it is still too high, reflecting a labor market and economy performing far short of their potential. At the same time, inflation has been running below the Federal Reserve's goal of 2 percent and is expected to continue to do so for some time.

For these reasons, the Federal Reserve is using its monetary policy tools to promote a more robust recovery. A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases. I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.”

In his classic restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958, 86):

“The assumption that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates and differfrom each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969) provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus, g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Ibid). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (10

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

In delivering the biannual report on monetary policy (Board of Governors 2013Jul17), Chairman Bernanke (2013Jul17) advised Congress that:

“Instead, we are providing additional policy accommodation through two distinct yet complementary policy tools. The first tool is expanding the Federal Reserve's portfolio of longer-term Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS); we are currently purchasing $40 billion per month in agency MBS and $45 billion per month in Treasuries. We are using asset purchases and the resulting expansion of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet primarily to increase the near-term momentum of the economy, with the specific goal of achieving a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market in a context of price stability. We have made some progress toward this goal, and, with inflation subdued, we intend to continue our purchases until a substantial improvement in the labor market outlook has been realized. We are relying on near-zero short-term interest rates, together with our forward guidance that rates will continue to be exceptionally low--our second tool--to help maintain a high degree of monetary accommodation for an extended period after asset purchases end, even as the economic recovery strengthens and unemployment declines toward more-normal levels. In appropriate combination, these two tools can provide the high level of policy accommodation needed to promote a stronger economic recovery with price stability.

The Committee's decisions regarding the asset purchase program (and the overall stance of monetary policy) depend on our assessment of the economic outlook and of the cumulative progress toward our objectives. Of course, economic forecasts must be revised when new information arrives and are thus necessarily provisional.”

Friedman (1953) argues there are three lags in effects of monetary policy: (1) between the need for action and recognition of the need; (2) the recognition of the need and taking of actions; and (3) taking of action and actual effects. Friedman (1953) finds that the combination of these lags with insufficient knowledge of the current and future behavior of the economy causes discretionary economic policy to increase instability of the economy or standard deviations of real income σy and prices σp. Policy attempts to circumvent the lags by policy impulses based on forecasts. We are all naïve about forecasting. Data are available with lags and revised to maintain high standards of estimation. Policy simulation models estimate economic relations with structures prevailing before simulations of policy impulses such that parameters change as discovered by Lucas (1977). Economic agents adjust their behavior in ways that cause opposite results from those intended by optimal control policy as discovered by Kydland and Prescott (1977). Advance guidance attempts to circumvent expectations by economic agents that could reverse policy impulses but is of dubious effectiveness. There is strong case for using rules instead of discretionary authorities in monetary policy (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/search?q=rules+versus+authorities).

The key policy is maintaining fed funds rate between 0 and ¼ percent. An increase in fed funds rates could cause flight out of risk financial markets worldwide. There is no exit from this policy without major financial market repercussions. Indefinite financial repression induces carry trades with high leverage, risks and illiquidity.

Unconventional monetary policy drives wide swings in allocations of positions into risk financial assets that generate instability instead of intended pursuit of prosperity without inflation. There is insufficient knowledge and imperfect tools to maintain the gap of actual relative to potential output constantly at zero while restraining inflation in an open interval of (1.99, 2.0). Symmetric targets appear to have been abandoned in favor of a self-imposed single jobs mandate of easing monetary policy even with the economy growing at or close to potential output that is actually a target of growth forecast. The impact on the overall economy and the financial system of errors of policy are magnified by large-scale policy doses of trillions of dollars of quantitative easing and zero interest rates. The US economy has been experiencing financial repression as a result of negative real rates of interest during nearly a decade and programmed in monetary policy statements until 2015 or, for practical purposes, forever. The essential calculus of risk/return in capital budgeting and financial allocations has been distorted. If economic perspectives are doomed until 2015 such as to warrant zero interest rates and open-ended bond-buying by “printing” digital bank reserves (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html; see Shultz et al 2012), rational investors and consumers will not invest and consume until just before interest rates are likely to increase. Monetary policy statements on intentions of zero interest rates for another three years or now virtually forever discourage investment and consumption or aggregate demand that can increase economic growth and generate more hiring and opportunities to increase wages and salaries. The doom scenario used to justify monetary policy accentuates adverse expectations on discounted future cash flows of potential economic projects that can revive the economy and create jobs. If it were possible to project the future with the central tendency of the monetary policy scenario and monetary policy tools do exist to reverse this adversity, why the tools have not worked before and even prevented the financial crisis? If there is such thing as “monetary policy science”, why it has such poor record and current inability to reverse production and employment adversity? There is no excuse of arguing that additional fiscal measures are needed because they were deployed simultaneously with similar ineffectiveness.

In remarkable anticipation in 2005, Professor Raghuram G. Rajan (2005) warned of low liquidity and high risks of central bank policy rates approaching the zero bound (Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 218-9). Professor Rajan excelled in a distinguished career as an academic economist in finance and was chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Shefali Anand and Jon Hilsenrath, writing on Oct 13, 2013, on “India’s central banker lobbies Fed,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304330904579133530766149484?KEYWORDS=Rajan), interviewed Raghuram G Rajan, who is the current Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, which is India’s central bank (http://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/AboutusDisplay.aspx). In this interview, Rajan argues that central banks should avoid unintended consequences on emerging market economies of inflows and outflows of capital triggered by monetary policy. Portfolio reallocations induced by combination of zero interest rates and risk events stimulate carry trades that generate wide swings in world capital flows. Professor Rajan, in an interview with Kartik Goyal of Bloomberg (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-01-30/rajan-warns-of-global-policy-breakdown-as-emerging-markets-slide.html), warns of breakdown of global policy coordination.

Professor Ronald I. McKinnon (2013Oct27), writing on “Tapering without tears—how to end QE3,” on Oct 27, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304799404579153693500945608?KEYWORDS=Ronald+I+McKinnon), finds that the major central banks of the world have fallen into a “near-zero-interest-rate trap.” World economic conditions are weak such that exit from the zero interest rate trap could have adverse effects on production, investment and employment. The maintenance of interest rates near zero creates long-term near stagnation. The proposal of Professor McKinnon is credible, coordinated increase of policy interest rates toward 2 percent. Professor John B. Taylor at Stanford University, writing on “Economic failures cause political polarization,” on Oct 28, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303442004579121010753999086?KEYWORDS=John+B+Taylor), analyzes that excessive risks induced by near zero interest rates in 2003-2004 caused the financial crash. Monetary policy continued in similar paths during and after the global recession with resulting political polarization worldwide.

Table IV-2 provides economic projections of governors of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and regional presidents of Federal Reserve Banks released at the meeting of Dec 18, 2013. The Fed releases the data with careful explanations (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf). Columns “∆% GDP,” “∆% PCE Inflation” and “∆% Core PCE Inflation” are changes “from the fourth quarter of the previous year to the fourth quarter of the year indicated.” The GDP report for IIIQ2013 is analyzed in Section I (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html). and the PCE inflation data from the report on personal income and outlays in Section IV (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html). The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides the estimate of IIQ2013 GDP released on Sep 26 with revisions since 1929 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/gdpnewsrelease.htm http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html). The BEA provides the first estimate of IIIQ2013 GDP released on Nov 8, 2013 and the third estimate of IIIQ2013 GDP on Dec 20, 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html). The Bureau of Economic Analysis provides the estimate of IVQ2013 GDP (Section I). PCE inflation is the index of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) of the report of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on “Personal Income and Outlays” (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/pinewsrelease.htm), which is analyzed in Section IV (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html). The report on “Personal Income and Outlays” for Sep 2013 was released on Nov 8, 2013, the report for Oct 2013 was released on Dec 6, 2013, the report for Nov 2013 was released on Dec 23, 2013 and the report for Dec 2013 was released on Jan 31, 214 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html). PCE core inflation consists of PCE inflation excluding food and energy. Column “UNEMP %” is the rate of unemployment measured as the average civilian unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of the year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides the Employment Situation Report with the civilian unemployment rate in the first Friday of every month, which is analyzed in this blog. The report for Jul 2013 was released on Aug 2 and analyzed in this blog and the report for Aug 2013 was released on Sep 6, 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html

and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/risks-of-steepening-yield-curve-and.html). The report for Sep 2013 was released on Oct 22, 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html

and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html). The report for Oct 2013 was released on Nov 8, 2013 and the report for Nov 2013 on Dec 6, 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html). The report for Dec 2013 was released on Jan 10, 2014 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html). “Longer term projections represent each participant’s assessment of the rate to which each variable would be expected to converge under appropriate monetary policy and in the absence of further shocks to the economy” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20121212.pdf).

It is instructive to focus on 2013, 2014 and 2015 because 2016 and longer term are too far away, and there is not much information even on what will happen in 2013-2015 and beyond. The central tendency should provide reasonable approximation of the view of the majority of members of the FOMC but the second block of numbers provides the range of projections by FOMC participants. The first row for each year shows the projection introduced after the meeting of Dec 18, 2013 and the second row “PR” the projection of the Sep 18, 2013 meeting. There are three major changes in the view.

1. Growth “∆% GDP.” The FOMC has increased the forecast of GDP growth in 2013 from 2.0 to 2.3 percent at the meeting in Sep 2013 to 2.2 to 2.3 percent at the meeting on Dec 18, 2013. The FOMC increased GDP growth in 2014 from 2.9 to 3.1 percent at the meeting in Sep 2013 to 2.8 to 3.2 percent at the meeting in Dec 2013.

2. Rate of Unemployment “UNEM%.” The FOMC reduced the forecast of the rate of unemployment for 2013 from 7.1 to 7.3 percent at the meeting on Sep 18, 2013 to 7.0 to 7.1 percent at the meeting on Dec 18, 2013. The projection for 2014 decreased to the range of 6.3 to 6.6 in Dec 2013 from 6.4 to 6.8 in Sep 2013. Projections of the rate of unemployment are moving closer to the desire 6.5 percent or lower with 5.8 to 6.1 percent in 2015 after the meeting on Dec 18, 2013.

3. Inflation “∆% PCE Inflation.” The FOMC changed the forecast of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation for 2014 from 1.3 to 1.8 percent at the meeting on Sep 18, 2013 to 1.4 to 1.6 percent at the meeting on Dec 18, 2013. There are no projections exceeding 2.0 percent in the central tendency but some in the range reach 2.3 percent in 2015 and 2016. The longer run projection is at 2.0 percent.

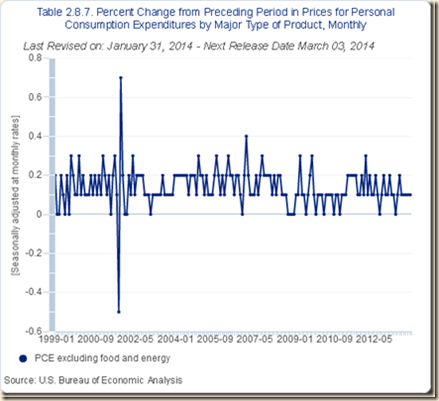

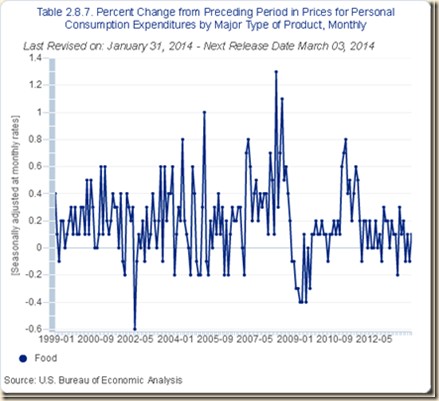

4. Core Inflation “∆% Core PCE Inflation.” Core inflation is PCE inflation excluding food and energy. There is again not much of a difference of the projection for 2014, changing from 1.5 to 1.7 percent at the meeting on Sep 18, 2013 to 1.4 to 1.6 percent at the meeting Dec 18, 2013. In 2015, there is minor change in the projection from 1.7 to 2.0 percent at the meeting on Sep 18, 2013 to 1.6 to 2.0 percent on Dec 18, 2013. The rate of change of the core PCE is below 2.0 percent in the central tendency with 2.3 percent at the top of the range in 2015 and 2016.

Table IV-2, US, Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents in FOMC, Sep 18, 2013 and Dec 18, 2013

| ∆% GDP | UNEM % | ∆% PCE Inflation | ∆% Core PCE Inflation | |

| Central | ||||

| 2013 | 2.2 to 2.3 | 7.0 to 7.1 | 0.9 to 1.0 | 1.1 to 1.2 1.2 to 1.3 |

| 2014 | 2.8 to 3.2 | 6.3 to 6.6 | 1.4 to 1.6 | 1.4 to 1.6 |

| 2015 Sep PR | 3.0 to 3.4 3.0 to 3.5 | 5.8 to 6.1 5.9 to 6.2 | 1.5 to 2.0 1.6 to 2.0 | 1.6 to 2.0 1.7 to 2.0 |

| 2016 Sep PR | 2.5 to 3.2 2.5 to 3.3 | 5.3 to 5.8 5.4 to 5.9 | 1.7 to 2.0 1.7 to 2.0 | 1.8 to 2.0 1.9 to 2.0 |

| Longer Run Sep PR | 2.2 to 2.4 2.2 to 2.5 | 5.2 to 5.8 5.2 to 5.8 | 2.0 2.0 | |

| Range | ||||

| 2013 | 2.2 to 2.4 | 7.0 to 7.1 | 0.9 to 1.2 | 1.1 to 1.2 |

| 2014 | 2.2 to 3.3 | 6.2 to 6.7 | 1.3 to 1.8 | 1.3 to 1.8 |

| 2015 Sep PR | 2.2 to 3.6 2.2 to 3.7 | 5.5 to 6.2 5.3 to 6.3 | 1.4 to 2.3 1.4 to 2.3 | 1.5 to 2.3 1.6 to 2.3 |

| 2016 Sep PR | 2.1 to 3.5 2.2 to 3.5 | 5.0 to 6.0 5.2 to 6.0 | 1.6 to 2.2 1.5 to 2.3 | 1.6 to 2.2 1.7 to 2.3 |

| Longer Run Jun PR | 1.8 to 2.5 2.1 to 2.5 | 5.2 to 6.0 5.2 to 6.0 | 2.0 2.0 |

Notes: UEM: unemployment; PR: Projection

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf

Another important decision at the FOMC meeting on Jan 25, 2012, is formal specification of the goal of inflation of 2 percent per year but without specific goal for unemployment (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125c.htm):

“Following careful deliberations at its recent meetings, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has reached broad agreement on the following principles regarding its longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy. The Committee intends to reaffirm these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual organizational meeting each January.

The FOMC is firmly committed to fulfilling its statutory mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity facilitates well-informed decision making by households and businesses, reduces economic and financial uncertainty, increases the effectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society.

Inflation, employment, and long-term interest rates fluctuate over time in response to economic and financial disturbances. Moreover, monetary policy actions tend to influence economic activity and prices with a lag. Therefore, the Committee's policy decisions reflect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments of the balance of risks, including risks to the financial system that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals.

The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation. The Committee judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve's statutory mandate. Communicating this inflation goal clearly to the public helps keep longer-term inflation expectations firmly anchored, thereby fostering price stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhancing the Committee's ability to promote maximum employment in the face of significant economic disturbances.

The maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market. These factors may change over time and may not be directly measurable. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a fixed goal for employment; rather, the Committee's policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the maximum level of employment, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments. Information about Committee participants' estimates of the longer-run normal rates of output growth and unemployment is published four times per year in the FOMC's Summary of Economic Projections. For example, in the most recent projections, FOMC participants' estimates of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment had a central tendency of 5.2 percent to 6.0 percent, roughly unchanged from last January but substantially higher than the corresponding interval several years earlier.

In setting monetary policy, the Committee seeks to mitigate deviations of inflation from its longer-run goal and deviations of employment from the Committee's assessments of its maximum level. These objectives are generally complementary. However, under circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it follows a balanced approach in promoting them, taking into account the magnitude of the deviations and the potentially different time horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate. ”

The probable intention of this specific inflation goal is to “anchor” inflationary expectations. Massive doses of monetary policy of promoting growth to reduce unemployment could conflict with inflation control. Economic agents could incorporate inflationary expectations in their decisions. As a result, the rate of unemployment could remain the same but with much higher rate of inflation (see Kydland and Prescott 1977 and Barro and Gordon 1983; http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html See Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 99-116). Strong commitment to maintaining inflation at 2 percent could control expectations of inflation.

The FOMC continues its efforts of increasing transparency that can improve the credibility of its firmness in implementing its dual mandate. Table IV-3 provides the views by participants of the FOMC of the levels at which they expect the fed funds rate in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and the in the longer term. Table IV-3 is inferred from a chart provided by the FOMC with the number of participants expecting the target of fed funds rate (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf). There are 17 participants expecting the rate to remain at 0 to ¼ percent in 2013. The rate would still remain at 0 to ¼ percent in 2014 for 15 participants with one expecting the rate to be in the range of 0.5 to 1.0 percent and one participant expecting rates at 1.0 to 1.5 percent. This table is consistent with the guidance statement of the FOMC that rates will remain at low levels. For 2015, ten participants expect rates to be below or at 1.0 percent while four expect rates from 1.0 to 2.0 percent and three expecting rates in excess of 2.0 percent. For 2016, nine participants expect rates between 1.0 and 2.0 percent, four between 2.0 and 3.0 percent and four between 3.0 and 4.5 percent. In the long term, all 17 participants expect the fed funds rate in the range of 3.0 to 4.5 percent.

Table IV-3, US, Views of Target Federal Funds Rate at Year-End of Federal Reserve Board

Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents Participating in FOMC, Dec 18, 2013

| 0 to 0.25 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 1.0 to 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | 3.0 to 4.5 | |

| 2013 | 17 | |||||

| 2014 | 15 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2015 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2016 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Longer Run | 17 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf

Additional information is provided in Table IV-4 with the number of participants expecting increasing interest rates in the years from 2013 to 2016. It is evident from Table IV-4 that the prevailing view of the FOMC is for interest rates to continue at low levels in future years. This view is consistent with the economic projections of low economic growth, relatively high unemployment and subdued inflation provided in Table IV-2. The FOMC states that rates will continue to be low even after return of the economy to potential growth.

Table IV-4, US, Views of Appropriate Year of Increasing Target Federal Funds Rate of Federal

Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents Participating in FOMC, Dec 18, 2013

| Appropriate Year of Increasing Target Fed Funds Rate | Number of Participants |

| 2014 | 2 |

| 2015 | 12 |

| 2016 | 3 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20131218.pdf