Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, Interest Rate Risk, Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures, Destruction of Household Nonfinancial Wealth with Stagnating Total Real Wealth, United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities, United States Housing Collapse, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013

Executive Summary

I Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IA1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IA2 Financial Repression

IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

IIA Destruction of Household Nonfinancial Wealth with Stagnating Total Real Wealth

IIB United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IIA1 Transmission of Monetary Policy

IIB1 Functions of Banks

IIC United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IID Theory and Reality of Economic History and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

IIE United States Housing Collapse

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

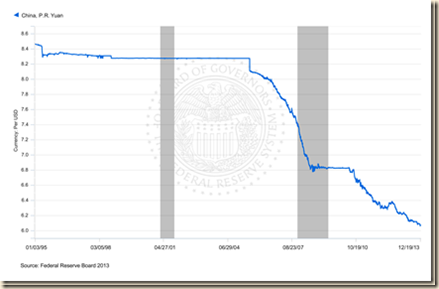

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

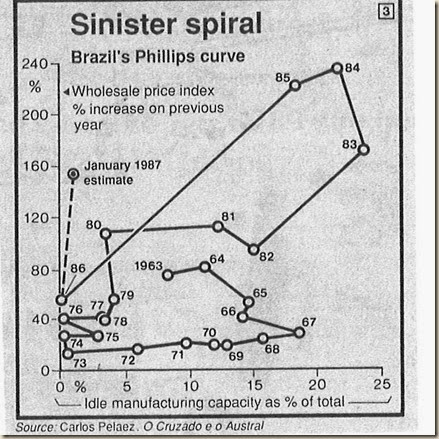

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

V World Economic Slowdown. Table V-1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx) to show GDP in dollars in 2012 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2013 to 2016. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has lowered its forecast of the world economy to 2.9 percent in 2013 but accelerating to 3.6 percent in 2014, 4.0 percent in 2015 and 4.1 percent in 2016. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $34,560 billion of world output of $72,216 billion, or 47.9 percent, but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 2.1 percent on average from 2013 to 2016 in contrast with 3.6 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would grow 15.4 percent in the four years from 2013 to 2016, the G7 as a whole would grow 8.6 percent. The difference in dollars of 2012 is rather high: growing by 15.4 percent would add $11.1 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly, two times the output of the economy of Japan of $5,960 billion but growing by 8.6 percent would add $6.2 trillion of output to the world, or about the output of Japan in 2012. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2012 of $27,221 billion, or 37.7 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 21.9 percent or at the average yearly rate of 5.1 percent, contributing $6.0 trillion from 2013 to 2016 or the equivalent of somewhat less than the GDP of $8,221 billion of China in 2012. The final four countries in Table V-1 often referred as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output in 2012 adds to $14,346 billion, or 19.9 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 41.5 percent of the combined output of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table V-1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2012 | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | |

| World | 72,216 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| G7 | 34,560 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Canada | 1,821 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| France | 2,614 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| DE | 3,430 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Japan | 5,960 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| UK | 2,477 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| US | 16,245 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Euro Area | 12,199 | -0.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| DE | 3,430 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| France | 2,614 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| POT | 212 | -1.8 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Ireland | 211 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Greece | 249 | -4.2 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Spain | 1,324 | -1.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| EMDE | 27,221 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| Brazil | 2,253 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Russia | 2,030 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| India | 1,842 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| China | 8,221 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); POT: Portugal

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx). Table V-2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2012 to 2016 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates for 2012 in Table V-2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 15.7 percent for Portugal (POT), 14.7 percent for Ireland, 24.2 percent for Greece, 25.0 percent for Spain and 10.6 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 7.4 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table V-2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2012 | % Labor Force 2013 | % Labor Force 2014 | % Labor Force 2015 | % Labor Force 2016 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| Canada | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 |

| France | 10.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.5 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 11.2 |

| Japan | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| UK | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| US | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 |

| Euro Area | 11.4 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 11.5 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| France | 10.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.5 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 11.2 |

| POT | 15.7 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 17.3 | 16.8 |

| Ireland | 14.7 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 12.4 |

| Greece | 24.2 | 27.0 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 21.0 |

| Spain | 25.0 | 26.9 | 26.7 | 26.5 | 26.2 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 5.5 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Russia | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| China | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

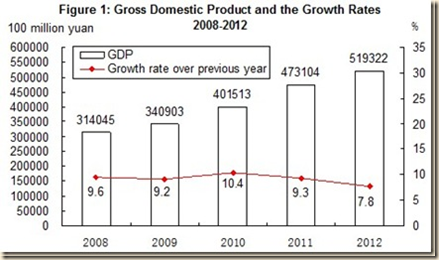

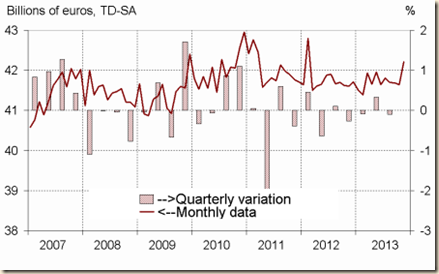

Table V-3 provides the latest available estimates of GDP for the regions and countries followed in this blog from IQ2012 to IIQ2013 available now for all countries. There are preliminary estimates for all countries for IIIQ2013. Growth is weak throughout most of the world. Japan’s GDP increased 0.9 percent in IQ2012 and 3.5 percent relative to a year earlier but part of the jump could be the low level a year earlier because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan is experiencing difficulties with the overvalued yen because of worldwide capital flight originating in zero interest rates with risk aversion in an environment of softer growth of world trade. Japan’s GDP fell 0.5 percent in IIQ2012 at the seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of minus 2.0 percent, which is much lower than 3.5 percent in IQ2012. Growth of 3.2 percent in IIQ2012 in Japan relative to IIQ2011 has effects of the low level of output because of Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan’s GDP contracted 0.8 percent in IIIQ2012 at the SAAR of minus 3.2 percent and decreased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP grew 0.1 percent in IVQ2012 at the SAAR of 0.6 percent and decreased 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan grew 1.1 percent in IQ2013 at the SAAR of 4.5 percent and 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP increased 0.9 percent in IIQ2013 at the SAAR of 3.6 percent and increased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. Japan’s GDP grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 at the SAAR of 1.1 percent and increased 2.4 pecent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.2 percent in IIQ2012, which annualizes to 9.1 percent and 7.6 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.0 percent in IIIQ2012, which annualizes at 8.2 percent and 7.4 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent, and 7.9 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, China grew at 1.5 percent, which annualizes at 6.1 percent and 7.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, China grew at 1.9 percent, which annualizes at 7.8 percent and 7.5 percent relative to a year earlier. China grew at 2.2 percent in IIIQ2013, which annualizes at 9.1 percent and 7.8 percent relative to a year earlier. There is decennial change in leadership in China (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/index.htm). Growth rates of GDP of China in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier have been declining from 2011 to 2013. GDP fell 0.1 percent in the euro area in IQ2012 and decreased 0.2 in IQ2012 relative to a year earlier. Euro area GDP contracted 0.3 percent IIQ2012 and fell 0.5 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.1 percent and declined 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. In IVQ2012, euro area GDP fell 0.5 percent relative to the prior quarter and fell 1.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, the GDP of the euro area fell 0.2 percent and decreased 1.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of the euro area increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2013 and fell 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, euro area GDP increased 0.1 percent and fell 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.7 percent in IQ2012 and 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2012, Germany’s GDP decreased 0.1 percent and increased 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier but 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier when adjusted for calendar (CA) effects. In IIIQ2012, Germany’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP contracted 0.5 percent in IVQ2012 and increased 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.0 percent and fell 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIQ2013, Germany’s GDP increased 0.7 percent and 0.9 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Germany increased 0.3 percent in IIIQ2013 and 1.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Growth of US GDP in IQ2012 was 0.9 percent, at SAAR of 3.7 percent and higher by 3.3 percent relative to IQ2011. US GDP increased 0.3 percent in IIQ2012, 1.2 percent at SAAR and 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, US GDP grew 0.7 percent, 2.8 percent at SAAR and 3.1 percent relative to IIIQ2011. In IVQ2012, US GDP grew 0.0 percent, 0.1 percent at SAAR and 2.0 percent relative to IVQ2011. In IQ2013, US GDP grew at 1.1 percent SAAR, 0.3 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.3 percent relative to the same quarter in 2013. In IIQ2013, US GDP grew at 2.5 percent in SAAR, 0.6 percent relative to the prior quarter and 1.6 percent relative to IIQ2012. US GDP grew at 4.1 percent in SAAR in IIIQ2013, 1.0 percent relative to the prior quarter and 2.0 percent relative to the same quarter a year earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html) with weak hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html). In IQ2012, UK GDP changed 0.0 percent, increasing 0.6 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP fell 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIIQ2012 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP fell 0.1 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IIIQ2012 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.5 percent in IQ2013 and 0.7 percent relative to a year earlier. UK GDP increased 0.8 percent in IIQ2013 and 2.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, UK GDP increased 0.8 percent and 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy has experienced decline of GDP in nine consecutive quarters from IIIQ2011 to IIIQ2013. Italy’s GDP fell 1.1 percent in IQ2012 and declined 1.8 percent relative to IQ2011. Italy’s GDP fell 0.6 percent in IIQ2012 and declined 2.6 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, Italy’s GDP fell 0.5 percent and declined 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy contracted 0.9 percent in IVQ2012 and fell 3.0 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, Italy’s GDP contracted 0.6 percent and fell 2.5 percent relative to a year earlier. Italy’s GDP fell 0.3 percent in IIQ2013 and 2.2 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of Italy changed 0.0 percent in IIIQ2013 and declined 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP changed 0.0 percent in IQ2012 and increased 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP decreased 0.3 percent in IIQ2012 and increased 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2012, France’s GDP increased 0.2 percent and changed 0.0 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP fell 0.2 percent in IVQ2012 and declined 0.3 percent relative to a year earlier. In IQ2013, France GDP fell 0.1 percent and declined 0.4 percent relative to a year earlier. The GDP of France increased 0.6 percent in IIQ2013 and 0.5 percent relative to a year earlier. France’s GDP contracted 0.1 percent in IIIQ2013 and increased 0.2 percent relative to a year earlier.

Table V-3, Percentage Changes of GDP Quarter on Prior Quarter and on Same Quarter Year Earlier, ∆%

| IQ2012/IVQ2011 | IQ2012/IQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.5 | 3.1 |

| China | 1.4 | 8.1 |

| Euro Area | -0.1 | -0.2 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| France | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| Italy | -1.1 | -1.8 |

| United Kingdom | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| IIQ2012/IQ2012 | IIQ2012/IIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.3 SAAR: 1.2 | 2.8 |

| Japan | QOQ: -0.5 | 3.2 |

| China | 2.2 | 7.6 |

| Euro Area | -0.3 | -0.5 |

| Germany | -0.1 | 0.6 1.1 CA |

| France | -0.3 | 0.1 |

| Italy | -0.6 | -2.6 |

| United Kingdom | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| IIIQ2012/ IIQ2012 | IIIQ2012/ IIIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Japan | QOQ: –0.8 | -0.2 |

| China | 2.0 | 7.4 |

| Euro Area | -0.1 | -0.7 |

| Germany | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| France | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Italy | -0.5 | -2.8 |

| United Kingdom | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| IVQ2012/IIIQ2012 | IVQ2012/IVQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.1 SAAR: 0.6 | -0.3 |

| China | 1.9 | 7.9 |

| Euro Area | -0.5 | -1.0 |

| Germany | -0.5 | 0.0 |

| France | -0.2 | -0.3 |

| Italy | -0.9 | -3.0 |

| United Kingdom | -0.1 | 0.2 |

| IQ2013/IVQ2012 | IQ2013/IQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Japan | QOQ: 1.1 SAAR: 4.5 | 0.1 |

| China | 1.5 | 7.7 |

| Euro Area | -0.2 | -1.2 |

| Germany | 0.0 | -1.6 |

| France | -0.1 | -0.4 |

| Italy | -0.6 | -2.5 |

| UK | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| IIQ2013/IQ2013 | IIQ2013/IIQ2012 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.6 SAAR: 2.5 | 1.6 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.9 SAAR: 3.6 | 1.2 |

| China | 1.9 | 7.5 |

| Euro Area | 0.3 | -0.6 |

| Germany | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| France | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Italy | -0.3 | -2.2 |

| UK | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| IIIQ2013/IIQ2013 | III/Q2013/ IIIQ2012 | |

| USA | QOQ: 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Japan | QOQ: 0.3 SAAR: 1.1 | 2.4 |

| China | 2.2 | 7.8 |

| Euro Area | 0.1 | -0.4 |

| Germany | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| France | -0.1 | 0.2 |

| Italy | 0.0 | -1.8 |

| UK | 0.8 | 1.9 |

QOQ: Quarter relative to prior quarter; SAAR: seasonally adjusted annual rate

Source: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

Table V-4 provides two types of data: growth of exports and imports in the latest available months and in the past 12 months; and contributions of net trade (exports less imports) to growth of real GDP. Japan provides the most worrisome data (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations_8763.html http://cmpass ocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/interest-rate-risks-duration-dumping.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/duration-dumping-steepening-yield-curve.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/06/paring-quantitative-easing-policy-and_4699.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/05/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states_24.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/contraction-of-united-states-real_25.html and for GDP http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocreulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/recovery-without-hiring-united-states.html). In Nov 2013, Japan’s exports grew 18.4 percent in 12 months while imports increased 21.1 percent. The second part of Table V-4 shows that net trade deducted 1.3 percentage points from Japan’s growth of GDP in IIQ2012, deducted 2.1 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2012 and deducted 0.6 percentage points from GDP growth in IVQ2012. Net trade added 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2012, 1.6 percentage points in IQ2013 and 0.6 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.9 percentage points from GDP growth in Japan. In Nov 2013, China exports increased 12.6 percent relative to a year earlier and imports increased 5.2 percent. Germany’s exports increased 0.2 percent in the month of Oct 2013 and increased 0.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Oct 2013. Germany’s imports decreased 2.9 percent in the month of Oct and decreased 1.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Oct. Net trade contributed 0.8 percentage points to growth of GDP in IQ2012, contributed 0.4 percentage points in IIQ2012, contributed 0.3 percentage points in IIIQ2012, deducted 0.5 percentage points in IVQ2012, deducted 0.2 percentage points in IQ2012 and added 0.3 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded deducted 0.4 percentage points from Germany’s GDP growth in IIIQ2013. Net trade deducted 0.8 percentage points from UK value added in IQ2012, deducted 0.8 percentage points in IIQ2012, added 0.7 percentage points in IIIQ2012 and subtracted 0.5 percentage points in IVQ2012. In IQ2013, net trade added 0.5 percentage points to UK’s growth of value added and contributed 0.2 percentage points in IIQ2013. In IIIQ2013, net trade deducted 1.2 percentage points from UK GDP growth. France’s exports decreased 0.3 percent in Oct 2013 while imports decreased 2.5. Net traded added 0.1 percentage points to France’s GDP in IIIQ2012 and 0.1 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade deducted 0.1 percentage points from France’s GDP growth in IQ2013 and added 0.1 percentage points in IIQ2013, deducting 0.6 percentage points in IIIQ2013. US exports increased 1.8 percent in Oct 2013 and goods exports increased 2.0 percent in Jan-Oct 2013 relative to a year earlier but net trade deducted 0.03 percentage points from GDP growth in IIIQ2012 and added 0.68 percentage points in IVQ2012. Net trade deducted 0.28 percentage points from US GDP growth in IQ2013 and deducted 0.07 percentage points in IIQ2013. Net traded added 0.14 percentage points to US GDP growth in IIIQ2013. US imports increased 0.4 percent in Oct 2013 and goods imports decreased 0.3 percent in Jan-Oct 2013 relative to a year earlier. Industrial production increased 1.1 percent in Nov 2013 after increasing 0.1 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 0.5 percent in Se 2013, as shown in Table I-1, with all data seasonally adjusted. The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production increased 1.1 percent in November after having edged up 0.1 percent in October; output was previously reported to have declined 0.1 percent in October. The gain in November was the largest since November 2012, when production rose 1.3 percent. Manufacturing output increased 0.6 percent in November for its fourth consecutive monthly gain. Production at mines advanced 1.7 percent to more than reverse a decline of 1.5 percent in October. The index for utilities was up 3.9 percent in November, as colder-than-average temperatures boosted demand for heating. At 101.3 percent of its 2007 average, total industrial production was 3.2 percent above its year-earlier level. In November, industrial production surpassed for the first time its pre-recession peak of December 2007 and was 21 percent above its trough of June 2009. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector increased 0.8 percentage point in November to 79.0 percent, a rate 1.2 percentage points below its long-run (1972-2012) average.”

In the six months ending in Nov 2013, United States national industrial production accumulated increase of 2.2 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 4.5 percent, which is higher than growth of 3.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. Excluding growth of 1.1 percent in Nov 2013, growth in the remaining five months from Jun 2012 to Oct 2013 accumulated to 1.1 percent or 2.2 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production fell in one of the past six months. Business equipment accumulated growth of 1.4 percent in the six months from Jun to Nov 2013 at the annual equivalent rate of 2.8 percent, which is higher than growth of 2.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “Capacity utilization for the industrial sector increased 0.8 percentage point in November to 79.0 percent, a rate 1.2 percentage points below its long-run (1972-2012) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate with possible acceleration in Nov 2013.

Manufacturing increased 0.3 percent in Oct 2013 after increasing 0.1 percent in Sep 2013 and increasing 0.7 percent in Aug 2013 seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.4 percent not seasonally adjusted in 12 months ending in Oct 2013, as shown in Table I-2 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-unwinding-monetary-policy.html). Manufacturing increased 0.6 percent in No 2013 after increasing 0.5 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 0.1 percent in Sep 2013 seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.0 percent not seasonally adjusted in 12 months ending in Nov 2013, as shown in Table I-2. Manufacturing grew cumulatively 1.7 percent in the six months ending in Nov 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 3.4 percent. Excluding the increase of 0.6 percent in Nov 2013, manufacturing accumulated growth of 1.1 percent from Jun 2013 to Oct 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 2.2 percent. Table I-2 provides a longer perspective of manufacturing in the US. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 into more recent months as shown by 12 months rates of growth. Growth rates appeared to be increasing again closer to 5 percent in Apr-Jun 2012 but deteriorated. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appeared to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession but the pace of manufacturing fell steadily in the past six months with some weakness at the margin. Manufacturing fell by 21.9 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increase by 16.8 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2012. Manufacturing grew 20.5 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Nov 2013. Manufacturing output in Nov 2013 is 5.9 percent below the peak in Jun 2007.

Table V-4, Growth of Trade and Contributions of Net Trade to GDP Growth, ∆% and % Points

| Exports | Exports 12 M ∆% | Imports | Imports 12 M ∆% | |

| USA | 1.8 Oct | 2.0 Jan-Oct | 0.4 Oct | -0.3 Jan-Oct |

| Japan | Nov 2013 18.4 Oct 2013 18.6 Sep 2013 11.5 Aug 2013 14.7 Jul 2013 12.2 Jun 2013 7.4 May 2013 10.1 Apr 2013 3.8 Mar 2013 1.1 Feb 2013 -2.9 Jan 2013 6.4 Dec -5.8 Nov -4.1 Oct -6.5 Sep -10.3 Aug -5.8 Jul -8.1 | Nov 2013 21.1 Oct 2013 26.1 Sep 2013 16.5 Aug 2013 16.0 Jul 2013 19.6 Jun 2013 11.8 May 2013 10.0 Apr 2013 9.4 Mar 2013 5.5 Feb 2013 7.3 Jan 2013 7.3 Dec 1.9 Nov 0.8 Oct -1.6 Sep 4.1 Aug -5.4 Jul 2.1 | ||

| China | 12.6 Nov 5.6 Oct -0.3 Sep 7.2 Aug 5.1 Jul -3.1 Jun 1.0 May 14.7 Apr 10.0 Mar 21.8 Feb | 5.2 Nov 7.6 Oct 7.4 Sep 10.9 Jul -0.7 Jun -0.3 May 16.8 Apr 14.1 Mar -15.2 Feb | ||

| Euro Area | 1.2 12-M Oct | 0.9 Jan-Oct | -3.4 12-M Oct | -3.4 Jan-Oct |

| Germany | 0.2 Oct CSA | 0.6 Oct | -2.9 Oct CSA | -1.6 Oct |

| France Oct | -0.3 | -2.0 | -2.5 | -2.7 |

| Italy Oct | -0.5 | 0.8 | -2.6 | -4.3 |

| UK | -1.4 Oct | 1.9 Aug-Oct 13 /Aug-Oct 12 | -1.4 Oct | 0.3 Aug-Oct 13/Aug-Oct 12 |

| Net Trade % Points GDP Growth | % Points | |||

| USA | IIIQ2013 0.14 IIQ2013 -0.07 IQ2013 -0.28 IVQ2012 +0.68 IIIQ2012 -0.03 IIQ2012 +0.10 IQ2012 +0.44 | |||

| Japan | 0.4 IQ2012 -1.3 IIQ2012 -2.1 IIIQ2012 -0.6 IVQ2012 1.6 IQ2013 0.6 IIQ2013 -1.9 IIIQ2013 | |||

| Germany | IQ2012 0.8 IIQ2012 0.4 IIIQ2012 0.3 IVQ2012 -0.5 IQ2013 -0.2 IIQ2013 0.3 IIIQ2013 -0.4 | |||

| France | 0.1 IIIQ2012 0.1 IVQ2012 -0.1 IQ2013 0.1 IIQ2013 -0.6 IIIQ2013 | |||

| UK | -0.8 IQ2012 -0.8 IIQ2012 +0.7 IIIQ2012 -0.5 IVQ2012 0.5 IQ2013 0.2 IIQ2013 -1.2 IIIQ2013 |

Sources: Country Statistical Agencies http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/ http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The geographical breakdown of exports and imports of Japan with selected regions and countries is provided in Table VB-7 for Nov 2013. The share of Asia in Japan’s trade is more than one-half for 55.0 percent of exports and 45.4 percent of imports. Within Asia, exports to China are 19.4 percent of total exports and imports from China 23.4 percent of total imports. While exports to China increased 33.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013, imports from China increased 19.4 percent. The second largest export market for Japan in Nov 2013 is the US with share of 19.2 percent of total exports, which is almost equal to that of China, and share of imports from the US of 9.0 percent in total imports. Western Europe has share of 10.2 percent in Japan’s exports and of 10.1 percent in imports. Rates of growth of exports of Japan in Nov 2013 are relatively high for several countries and regions with growth of 21.2 percent for exports to the US, 30.4 percent for exports to Brazil and 6.3 percent for exports to Australia. Comparisons relative to 2011 may have some bias because of the effects of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Deceleration of growth in China and the US and threat of recession in Europe can reduce world trade and economic activity. Growth rates of imports in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013 are positive for all trading partners with exception of France. Imports from Asia increased 19.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013 while imports from China increased 19.4 percent. Data are in millions of yen, which may have effects of recent depreciation of the yen relative to the United States dollar (USD).

Table V-5, Japan, Value and 12-Month Percentage Changes of Exports and Imports by Regions and Countries, ∆% and Millions of Yen

| Nov 2013 | Exports | 12 months ∆% | Imports Millions Yen | 12 months ∆% |

| Total | 5,900,458 | 18.4 | 7,193,325 | 21.1 |

| Asia | 3,243,626 | 18.9 | 3,268,586 | 19.8 |

| China | 1,142,599 | 33.1 | 1,679,702 | 19.4 |

| USA | 1,131,304 | 21.2 | 647,248 | 34.9 |

| Canada | 68,688 | 15.2 | 96,957 | 7.6 |

| Brazil | 43,821 | 30.4 | 96,632 | 5.4 |

| Mexico | 74,569 | 0.2 | 35,001 | 11.0 |

| Western Europe | 600,981 | 17.1 | 728,480 | 7.6 |

| Germany | 165,555 | 25.9 | 201,831 | 6.1 |

| France | 48,177 | 28.7 | 102,161 | -4.9 |

| UK | 84,919 | -5.1 | 55,180 | -2.8 |

| Middle East | 228,322 | 24.7 | 1,379,683 | 33.4 |

| Australia | 128,145 | 6.3 | 387,037 | 14.3 |

Source: Japan, Ministry of Finance http://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/index_e.htm

World trade projections of the IMF are in Table V-6. There is increasing growth of the volume of world trade of goods and services from 2.9 percent in 2013 to 5.4 percent in 2015 and 5.1 percent on average from 2013 to 2018. World trade would be slower for advanced economies while emerging and developing economies (EMDE) experience faster growth. World economic slowdown would more challenging with lower growth of world trade.

Table V-6, IMF, Projections of World Trade, USD Billions, USD/Barrel and ∆%

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average ∆% 2013-2018 | |

| World Trade Volume (Goods and Services) | 2.9 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| Exports Goods & Services | 3.0 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| Imports Goods & Services | 2.8 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| Oil Price USD/Barrel | 104.49 | 101.35 | NA | NA |

| Value of World Exports Goods & Services $B | 23,164 | 24,367 | NA | NA |

| Value of World Exports Goods $B | 18,709 | 19,632 | NA | NA |

| Exports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | 3.5 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 5.9 |

| G7 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Imports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | 5.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 6.2 |

| G7 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.0 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.5 |

| G7 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods | ||||

| EMDE | -0.6 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -0.8 |

| G7 | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.007 |

Notes: Commodity Price Index includes Fuel and Non-fuel Prices; Commodity Industrial Inputs Price includes agricultural raw materials and metal prices; Oil price is average of WTI, Brent and Dubai

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/index.aspx

The JP Morgan Global All-Industry Output Index of the JP Morgan Manufacturing and Services PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, with high association with world GDP, increased to 54.3 in Nov from 52.1 in Oct, indicating expansion at a faster rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/7af9c543698844248210df3c25786468). This index has remained above the contraction territory of 50.0 during 52 consecutive months. The employment index decreased from 52.2 in Oct to 51.2 in Nov with input prices rising at a slower rate, new orders increasing at faster rate and output increasing at faster rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/7af9c543698844248210df3c25786468). The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, was higher at 53.2 in Nov from 52.1 in Oct, which is the highest reading since May 2011 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/a4686697a9494286b96442f90b55d90f). New export orders expanded at the fastest pace in 32 months (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/a4686697a9494286b96442f90b55d90f). David Hensley, Director of Global Economic Coordination at JP Morgan finds acceleration of global manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/a4686697a9494286b96442f90b55d90f). The HSBC Brazil Composite Output Index, compiled by Markit, decreased marginally from 52.0 in Oct to 51.8 in Nov, indicating moderate expansion of Brazil’s private sector (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/c12bfb84a41d428fbccd1dac97d000e5). The HSBC Brazil Services Business Activity index, compiled by Markit increased marginally from 52.1 in Oct to 52.3 in Nov, indicating continuing improvement in business activity in an nine-month high (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/c12bfb84a41d428fbccd1dac97d000e5). André Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil, at HSBC, finds that the reading is stronger than the average of 50.2 in IIIQ2013 but that intput prices increased at the highest rate since Feb 2012 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/c12bfb84a41d428fbccd1dac97d000e5). The HSBC Brazil Purchasing Managers’ IndexTM (PMI™) decreased from 50.2 in Oct to 49.7 in Nov, indicating marginal deterioration in manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/e9b9f4da681c42aea8f00ce2170931fd). André Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil at HSBC, finds weakness in the second month of IIIQ2013 after marginal contraction in all months in IIQ2013 with improvement in Oct 2013 that is not sustained in Nov 2013 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/e9b9f4da681c42aea8f00ce2170931fd).

VA United States. The Markit Flash US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) seasonally adjusted decreased to 54.4 in Dec from 54.7 in Nov with the three-month average at 53.6 indicating moderate growth (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/409f3a8ff2a240c08dd65c2f747cab56). New export orders registered 51.4 in Dec unchanged from 51.4 in No, indicating marginal expansion. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that manufacturing output is growing at 4.0 percent per year with positive effects on employment (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/409f3a8ff2a240c08dd65c2f747cab56). The Markit Flash US Services PMI™ Business Activity Index increased from 55.9 in Nov to 56.0 in Dec with the average at 53.7l, which is the lowest quarterly average in 2013 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/a3f2275774ad43e3b0e1b72f6b0b7b8b). Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that the surveys are consistent with growth at around 3 percent per year in IVQ2013 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/a3f2275774ad43e3b0e1b72f6b0b7b8b). The Markit US Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) increased to 54.3 in Nov from 51.8 in Oct, which is the best improvement since Jan (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/f2489cf394d94b409e04a2ffa7a8e36b). The index of new exports orders increased from 51.3 in Oct to 51.4 in Nov while total new orders increased from 52.7 in Oct to 56.2 in Nov. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that the index suggests growth of production at 2.5 percent annual rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/f2489cf394d94b409e04a2ffa7a8e36b). The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) of the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Report on Business® increased 0.9 percentage points from 56.4 in Oct to 57.3 in Nov, which indicates growth at a higher rate (http://www.ism.ws/ISMReport/MfgROB.cfm?navItemNumber=12942). The index of new orders increased 3.0 percentage points from 60.6 in Oct to 63.6 in Nov. The index of exports increased 2.5 percentage point from 57.0 in Oct to 59.5 in Nov, growing at a faster rate. The Non-Manufacturing ISM Report on Business® PMI decreased 4.2 percentage points from 59.7 in Oct to 55.5 in Nov, indicating growth of business activity/production during 52 consecutive months, while the index of new orders decreased 0.4 percentage points from 56.8 in Oct to 56.4 in Nov (http://www.ism.ws/ISMReport/NonMfgROB.cfm?navItemNumber=12943). Table USA provides the country economic indicators for the US.

Table USA, US Economic Indicators

| Consumer Price Index | Nov 12 months NSA ∆%: 1.2; ex food and energy ∆%: 1.7 Nov month SA ∆%: 0.0; ex food and energy ∆%: 0.2 |

| Producer Price Index | Nov 12-month NSA ∆%: 0.7; ex food and energy ∆% 1.3 |

| PCE Inflation | Nov 12-month NSA ∆%: headline 0.9; ex food and energy ∆% 1.1 |

| Employment Situation | Household Survey: Nov Unemployment Rate SA 7.0% |

| Nonfarm Hiring | Nonfarm Hiring fell from 63.8 million in 2006 to 52.0 million in 2012 or by 11.8 million |

| GDP Growth | BEA Revised National Income Accounts IIQ2012/IIQ2011 2.8 IIIQ2012/IIIQ2011 3.1 IVQ2012/IVQ2011 2.0 IQ2013/IQ2012 1.3 IIQ2013/IIQ2012 1.6 IIIQ2013/IIIQ2012 2.0 IQ2012 SAAR 3.7 IIQ2012 SAAR 1.2 IIIQ2012 SAAR 2.8 IVQ2012 SAAR 0.1 IQ2013 SAAR 1.1 IIQ2013 SAAR 2.5 IIIQ2013 SAAR 4.1 |

| Real Private Fixed Investment | SAAR IIIQ2013 5.9 ∆% IVQ2007 to IIIQ2013: minus 3.6% Blog 12/22/13 |

| Personal Income and Consumption | Nov month ∆% SA Real Disposable Personal Income (RDPI) SA ∆% 0.1 |

| Quarterly Services Report | IIIQ13/IIQ12 NSA ∆%: Financial & Insurance 0.6 |

| Employment Cost Index | Compensation Private IIIQ2013 SA ∆%: 0.4 |

| Industrial Production | Nov month SA ∆%: 1.1 Manufacturing Nov SA ∆% 0.6 Nov 12 months SA ∆% 2.9, NSA 3.0 |

| Productivity and Costs | Nonfarm Business Productivity IIIQ2013∆% SAAE 3.0; IIIQ2013/IIIQ2012 ∆% 0.3; Unit Labor Costs SAAE IIIQ2013 ∆% -1.4; IIIQ2013/IIIQ2012 ∆%: 2.1 Blog 12/22/2013 |

| New York Fed Manufacturing Index | General Business Conditions From Nov -2.21 to Dec 0.98 |

| Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook Index | General Index from Nov 6.5 to Dec 7.0 |

| Manufacturing Shipments and Orders | New Orders SA Oct ∆% -0.9 Ex Transport 0.0 Jan-Oct NSA New Orders 2.4 Ex transport 1.5 |

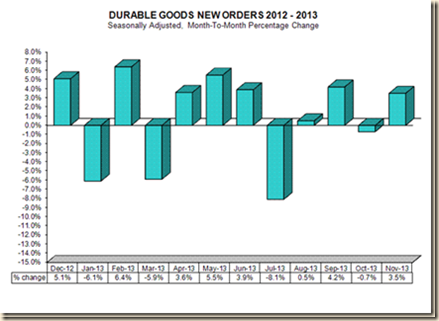

| Durable Goods | Nov New Orders SA ∆%: 3.5; ex transport ∆%: 1.2 |

| Sales of New Motor Vehicles | Jan-Nov 2013 14,239,897; Jan-Nov 2012 13,135,875. Nov 13 SAAR 16.41 million, Oct 13 SAAR 15.23 million, Nov 2012 SAAR 15.32 million Blog 12/8/13 |

| Sales of Merchant Wholesalers | Jan-Oct 2013/Jan-Oct 2012 NSA ∆%: Total 3.9; Durable Goods: 4.2; Nondurable |

| Sales and Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers | Oct 13/Oct 12-M NSA ∆%: Sales Total Business 4.0; Manufacturers 1.6 |

| Sales for Retail and Food Services | Jan-Nov 2013/Jan-Nov 2012 ∆%: Retail and Food Services 4.3; Retail ∆% 4.3 |

| Value of Construction Put in Place | Oct SAAR month SA ∆%: 0.8 Oct 12-month NSA: 2.5 Jan-Oct 2013 ∆% 5.0 |

| Case-Shiller Home Prices | Sep 2013/Sep 2012 ∆% NSA: 10 Cities 13.3; 20 Cities: 13.3 |

| FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only | Oct SA ∆% 0.5; |

| New House Sales | Nov 2013 month SAAR ∆%: minus 2.1 |

| Housing Starts and Permits | Nov Starts month SA ∆% 22.7; Permits ∆%: -3.1 |

| Trade Balance | Balance Oct SA -$40,641 million versus Sep -$38,945 million |

| Export and Import Prices | Nov 12-month NSA ∆%: Imports -1.5; Exports -1.6 |

| Consumer Credit | Oct ∆% annual rate: Total 7.1; Revolving 6.1; Nonrevolving 7.5 |

| Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term Treasury Securities | Oct Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term US Securities: $35.4 billion |

| Treasury Budget | Fiscal Year 2014/2013 ∆% Nov: Receipts 10.2; Outlays minus 4.7; Individual Income Taxes 2.7 Deficit Fiscal Year 2012 $1,087 billion Blog 12/15/2013 |

| CBO Budget and Economic Outlook | 2012 Deficit $1087 B 6.8% GDP Debt 11,281 B 70.1% GDP 2013 Deficit $642 B, Debt 12,036 B 72.5% GDP Blog 8/26/12 11/18/12 2/10/13 9/22/13 |

| Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities | Nov 2013 SAAR ∆%: Securities 4.6 Loans 1.0 Cash Assets 30.5 Deposits 3.7 Blog 12/29/13 |

| Flow of Funds | IIIQ2013 ∆ since 2007 Assets +$8554.2 MM Nonfinancial -$1228.7 MM Real estate -$1838.9 MM Financial +9782.9 MM Net Worth +$9269.0 MM Blog 12/29/13 |

| Current Account Balance of Payments | IIIQ2013 -110,055 MM %GDP 2.2 Blog 12/22/13 |

Links to blog comments in Table USA:

12/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html

12/15/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html

12/8/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/exit-risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html

12/1/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/exit-risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html

11/24/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html

9/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

2/10/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

11/18/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html

Manufacturers’ shipments of durable goods increased 1.8 percent in Nov 2013 and 0.6 percent in Oct 2013, increasing 0.5 percent in Sep 2013. New orders increased 3.5 percent in Nov 2013 after decreasing 0.7 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 4.2 percent in Sep 2013, as shown in Table VA-1. These data are very volatile. Volatility is illustrated by decrease of 12.9 percent in Nov 2012 after increase of orders for nondefense aircraft of 2642.2 percent in Sep 2012 after decrease of 97.2 percent in Aug and increases of 51.1 percent in Jul 2012 and 32.5 percent in Jun 2012. Nondefense aircraft new orders increased 21.8 percent in Nov 2013 after decreasing 5.3 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 59.2 percent in Nov 2013. New orders excluding transportation equipment increased 1.2 percent in Nov 2013, increased 0.7 percent in Oct 2013 and 0.3 percent in Sep 2013. Capital goods new orders, indicating investment increased 9.1 percent in Nov 2013, decreasing 2.7 percent in Oct 2013 but falling 8.2 percent in Sep 2013. New orders of nondefense capital goods increased 9.4 percent in Nov 2013, after decreasing 0.9 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 7.0 percent in Sep 2013. Capital goods orders excluding volatile aircraft increased 4.5 percent in Nov 2013, decreasing 0.7 percent in Oct 2013 and 1.2 percent in Sep 2013.

Table VA-1, US, Durable Goods Value of Manufacturers’ Shipments and New Orders, SA, Month ∆%

| Nov 2013 | Oct 2013 ∆% | Sep 2013 | |

| Total | |||

| S | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| NO | 3.5 | -0.7 | 4.2 |

| Excluding | |||

| S | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| NO | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Excluding | |||

| S | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| NO | 3.5 | 0.2 | 3.6 |

| Machinery | |||

| S | 4.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| NO | 3.8 | 1.0 | -1.7 |

| Computers & Electronic Products | |||

| S | 1.6 | -1.8 | 0.8 |

| NO | 1.7 | 2.4 | 5.0 |

| Computers | |||

| S | 5.1 | -10.2 | 5.4 |

| NO | 5.3 | -8.8 | 8.5 |

| Transport | |||

| S | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| NO | 8.4 | -3.5 | 13.1 |

| Motor Vehicles | |||

| S | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 |

| NO | 3.3 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Nondefense | |||

| S | -7.5 | 1.8 | 4.0 |

| NO | 21.8 | -5.3 | 59.2 |

| Capital Goods | |||

| S | 2.3 | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| NO | 9.1 | -2.7 | 8.2 |

| Nondefense Capital Goods | |||

| S | 1.3 | -0.2 | 0.5 |

| NO | 9.4 | -0.9 | 7.0 |

| Capital Goods ex Aircraft | |||

| S | 2.8 | -0.4 | -0.1 |

| NO | 4.5 | -0.7 | -1.2 |

Note: Mfg: manufacturing; S: shipments; NO: new orders; Transport: transportation

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/

Chart VA-1 provides monthly changes in durable goods new orders. There is significant volatility in these data, preventing clear identification of trends.

Chart VA-1, US, Manufacturers’ Durable Goods New Orders 2010-2011

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/briefrm/esbr/www/esbr021.html

Additional perspective on manufacturers’ shipments and new orders of durable goods is in Table VA-2. Values are cumulative millions of dollars in Jan-Nov 2013 not seasonally adjusted (NSA) and without adjustment for inflation. Shipments of all manufacturing industries in Jan-Oct 2013 total $2533.8 billion and new orders total $2504.7 billion, growing respectively by 3.4 percent and 5.3 percent relative to the same period in 2012. Excluding transportation equipment, shipments grew 1.6 percent and new orders increased 3.6 percent. Excluding defense, shipments grew 3.6 percent and new orders grew 6.4 percent. Important information not in Table VA-2 is the large share of nondurable goods: with shipments of $3 trillion in 2012, growing by 2.0 percent, and new orders of $3 trillion, growing by 2.0 percent, in part driven by higher prices for food and energy. Durable goods were lower in value in 2012, with shipments of $2.7 trillion, growing by 7.0 percent, and new orders of $2.6 trillion, growing by 4.1 percent. Capital goods have relatively high value of $909.6 billion for shipments, growing 2.0 percent, and new orders $954.9 billion, growing 5.7 percent. Excluding aircraft, capital goods shipments reached $718.4 billion, growing by 1.4 percent, and new orders $739.3 billion, growing 4.3 percent. Data weakened in 2013 with effects of lower inflation on nominal values with recovery later in the year.

Table VA-2, US, Value of Manufacturers’ Shipments and New Orders of Durable Goods, NSA, Millions of Dollars

| Jan-Nov 2013 | Shipments | ∆% 2013/ 2012 | New Orders | ∆% 2013/ |

| Total | 2,533,775 | 3.4 | 2,504,660 | 5.3 |

| Excluding Transport | 1,779,503 | 1.6 | 1,725,220 | 3.6 |

| Excluding Defense | 2,400,700 | 3.6 | 2,392,345 | 6.4 |

| Machinery | 375,771 | 3.0 | 381,423 | 7.4 |

| Computers & Electronic Products | 301,469 | -3.4 | 230,624 | -2.3 |

| Computers & Related Products | 24,123 | -7.2 | 24,283 | -8.5 |

| Transport Equipment | 754,272 | 8.1 | 779,440 | 9.3 |

| Motor Vehicles | 501,766 | 10.3 | 500,986 | 10.5 |

| Nondefense Aircraft | 120,577 | 8.0 | 166,269 | 25.9 |

| Capital Goods | 909,609 | 2.0 | 954,923 | 5.7 |

| Nondefense Capital Goods | 801,584 | 2.1 | 864,559 | 7.9 |

| Capital Goods ex Aircraft | 718,376 | 1.4 | 739,251 | 4.3 |

Note: Transport: transportation

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/

Chart VA-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System shows that output of durable manufacturing accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s with slower growth in the 2000s perhaps because processes matured. Growth was robust after the major drop during the global recession but appears to vacillate in the final segment.

Chart VA-2, US, Output of Durable Manufacturing, 1972-2013

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Manufacturing jobs increased 27,000 in Nov 2013 relative to Oct 2013, seasonally adjusted (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html). Manufacturing jobs not seasonally adjusted increased 83,000 from Nov 2012 to Nov 2013 or at the average monthly rate of 6,917. There are effects of the weaker economy and international trade together with the yearly adjustment of labor statistics. Industrial production increased 1.1 percent in Nov 2013 after increasing 0.1 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 0.5 percent in Se 2013, as shown in Table I-1, with all data seasonally adjusted. The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production increased 1.1 percent in November after having edged up 0.1 percent in October; output was previously reported to have declined 0.1 percent in October. The gain in November was the largest since November 2012, when production rose 1.3 percent. Manufacturing output increased 0.6 percent in November for its fourth consecutive monthly gain. Production at mines advanced 1.7 percent to more than reverse a decline of 1.5 percent in October. The index for utilities was up 3.9 percent in November, as colder-than-average temperatures boosted demand for heating. At 101.3 percent of its 2007 average, total industrial production was 3.2 percent above its year-earlier level. In November, industrial production surpassed for the first time its pre-recession peak of December 2007 and was 21 percent above its trough of June 2009. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector increased 0.8 percentage point in November to 79.0 percent, a rate 1.2 percentage points below its long-run (1972-2012) average.”

In the six months ending in Nov 2013, United States national industrial production accumulated increase of 2.2 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 4.5 percent, which is higher than growth of 3.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. Excluding growth of 1.1 percent in Nov 2013, growth in the remaining five months from Jun 2012 to Oct 2013 accumulated to 1.1 percent or 2.2 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production fell in one of the past six months. Business equipment accumulated growth of 1.4 percent in the six months from Jun to Nov 2013 at the annual equivalent rate of 2.8 percent, which is higher than growth of 2.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “Capacity utilization for the industrial sector increased 0.8 percentage point in November to 79.0 percent, a rate 1.2 percentage points below its long-run (1972-2012) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate with possible acceleration in Nov 2013.

Manufacturing increased 0.3 percent in Oct 2013 after increasing 0.1 percent in Sep 2013 and increasing 0.7 percent in Aug 2013 seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.4 percent not seasonally adjusted in 12 months ending in Oct 2013, as shown in Table I-2 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-unwinding-monetary-policy.html). Manufacturing increased 0.6 percent in No 2013 after increasing 0.5 percent in Oct 2013 and increasing 0.1 percent in Sep 2013 seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.0 percent not seasonally adjusted in 12 months ending in Nov 2013, as shown in Table I-2. Manufacturing grew cumulatively 1.7 percent in the six months ending in Nov 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 3.4 percent. Excluding the increase of 0.6 percent in Nov 2013, manufacturing accumulated growth of 1.1 percent from Jun 2013 to Oct 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of 2.2 percent. Table I-2 provides a longer perspective of manufacturing in the US. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 into more recent months as shown by 12 months rates of growth. Growth rates appeared to be increasing again closer to 5 percent in Apr-Jun 2012 but deteriorated. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appeared to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession but the pace of manufacturing fell steadily in the past six months with some weakness at the margin. Manufacturing fell by 21.9 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increase by 16.8 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2012. Manufacturing grew 20.5 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Nov 2013. Manufacturing output in Nov 2013 is 5.9 percent below the peak in Jun 2007.

Table Table VA-3 provides national income by industry without capital consumption adjustment (WCCA). “Private industries” or economic activities have share of 86.8 percent in IIIQ2013. Most of US national income is in the form of services. In Nov 2013, there were 137.942 million nonfarm jobs NSA in the US, according to estimates of the establishment survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm Table B-1). Total private jobs of 115.622 million NSA in Nov 2013 accounted for 83.8 percent of total nonfarm jobs of 137.942 million, of which 12.022 million, or 10.4 percent of total private jobs and 8.7 percent of total nonfarm jobs, were in manufacturing. Private service-producing jobs were 96.761 million NSA in Nov 2013, or 70.1 percent of total nonfarm jobs and 83.7 percent of total private-sector jobs. Manufacturing has share of 10.8 percent in US national income in IIQ2013, as shown in Table VA-3. Most income in the US originates in services. Subsidies and similar measures designed to increase manufacturing jobs will not increase economic growth and employment and may actually reduce growth by diverting resources away from currently employment-creating activities because of the drain of taxation.

Table VA-3, US, National Income without Capital Consumption Adjustment by Industry, Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates, Billions of Dollars, % of Total

| SAAR | % Total | SAAR IQ2013 | % Total | |

| National Income WCCA | 14,495.5 | 100.0 | 14,643.3 | 100.0 |

| Domestic Industries | 14,248.7 | 98.3 | 14,380.3 | 98.2 |

| Private Industries | 12,568.6 | 86.7 | 12,705.2 | 86.8 |

| Agriculture | 220.3 | 1.5 | 225.2 | 1.5 |

| Mining | 254.3 | 1.8 | 256.4 | 1.8 |

| Utilities | 216.5 | 1.5 | 221.2 | 1.5 |

| Construction | 629.0 | 4.3 | 639.1 | 4.4 |

| Manufacturing | 1558.9 | 10.8 | 1577.7 | 10.8 |

| Durable Goods | 888.1 | 6.1 | 910.1 | 6.2 |

| Nondurable Goods | 670.1 | 4.6 | 667.6 | 4.6 |

| Wholesale Trade | 874.4 | 6.0 | 884.0 | 6.0 |

| Retail Trade | 995.8 | 6.9 | 1000.2 | 6.8 |

| Transportation & WH | 436.3 | 3.0 | 443.6 | 3.0 |

| Information | 507.2 | 3.5 | 497.5 | 3.4 |

| Finance, Insurance, RE | 2448.1 | 16.9 | 2521.0 | 17.2 |

| Professional, BS | 2004.7 | 13.8 | 2004.0 | 13.7 |

| Education, Health Care | 1438.9 | 9.9 | 1439.2 | 9.8 |

| Arts, Entertainment | 577.1 | 4.0 | 585.2 | 4.0 |

| Other Services | 409.7 | 2.8 | 410.8 | 2.8 |

| Government | 1680.1 | 11.6 | 1675.1 | 11.4 |

| Rest of the World | 246.8 | 1.7 | 262.9 | 1.8 |

Notes: SSAR: Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rate; WCCA: Without Capital Consumption Adjustment by Industry; WH: Warehousing; RE, includes rental and leasing: Real Estate; Art, Entertainment includes recreation, accommodation and food services; BS: business services

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

VB Japan. Table VB-BOJF provides the forecasts of economic activity and inflation in Japan by the majority of members of the Policy Board of the Bank of Japan, which is part of their Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130711a.pdf). For fiscal 2013, the forecast is of growth of GDP between 2.6 and 3.0 percent, with the all items CPI less fresh food of 0.6 to 1.0 percent. The critical difference is forecast of the CPI excluding fresh food of 2.8 to 3.6 percent in 2014 and 1.6 to 2.9 percent in 2015. Consumer price inflation in Japan excluding fresh food was 0.3 percent in Oct 2013 and 0.9 percent in 12 months (http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/cpi/1581.htm). The new monetary policy of the Bank of Japan aims to increase inflation to 2 percent. These forecasts are biannual in Apr and Oct. The Cabinet Office, Ministry of Finance and Bank of Japan released on Jan 22, 2013, a “Joint Statement of the Government and the Bank of Japan on Overcoming Deflation and Achieving Sustainable Economic Growth” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130122c.pdf) with the important change of increasing the inflation target of monetary policy from 1 percent to 2 percent:

“The Bank of Japan conducts monetary policy based on the principle that the policy shall be aimed at achieving price stability, thereby contributing to the sound development of the national economy, and is responsible for maintaining financial system stability. The Bank aims to achieve price stability on a sustainable basis, given that there are various factors that affect prices in the short run.

The Bank recognizes that the inflation rate consistent with price stability on a sustainable basis will rise as efforts by a wide range of entities toward strengthening competitiveness and growth potential of Japan's economy make progress. Based on this recognition, the Bank sets the price stability target at 2 percent in terms of the year-on-year rate of change in the consumer price index.

Under the price stability target specified above, the Bank will pursue monetary easing and aim to achieve this target at the earliest possible time. Taking into consideration that it will take considerable time before the effects of monetary policy permeate the economy, the Bank will ascertain whether there is any significant risk to the sustainability of economic growth, including from the accumulation of financial imbalances.”

The Bank of Japan also provided explicit analysis of its view on price stability in a “Background note regarding the Bank’s thinking on price stability” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/data/rel130123a1.pdf http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/rel130123a.htm/). The Bank of Japan also amended “Principal terms and conditions for the Asset Purchase Program” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/rel130122a.pdf): “Asset purchases and loan provision shall be conducted up to the maximum outstanding amounts by the end of 2013. From January 2014, the Bank shall purchase financial assets and provide loans every month, the amount of which shall be determined pursuant to the relevant rules of the Bank.”

Financial markets in Japan and worldwide were shocked by new bold measures of “quantitative and qualitative monetary easing” by the Bank of Japan (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130404a.pdf). The objective of policy is to “achieve the price stability target of 2 percent in terms of the year-on-year rate of change in the consumer price index (CPI) at the earliest possible time, with a time horizon of about two years” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130404a.pdf). The main elements of the new policy are as follows:

- Monetary Base Control. Most central banks in the world pursue interest rates instead of monetary aggregates, injecting bank reserves to lower interest rates to desired levels. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has shifted back to monetary aggregates, conducting money market operations with the objective of increasing base money, or monetary liabilities of the government, at the annual rate of 60 to 70 trillion yen. The BOJ estimates base money outstanding at “138 trillion yen at end-2012) and plans to increase it to “200 trillion yen at end-2012 and 270 trillion yen at end 2014” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130404a.pdf).

- Maturity Extension of Purchases of Japanese Government Bonds. Purchases of bonds will be extended even up to bonds with maturity of 40 years with the guideline of extending the average maturity of BOJ bond purchases from three to seven years. The BOJ estimates the current average maturity of Japanese government bonds (JGB) at around seven years. The BOJ plans to purchase about 7.5 trillion yen per month (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/rel130404d.pdf). Takashi Nakamichi, Tatsuo Ito and Phred Dvorak, wiring on “Bank of Japan mounts bid for revival,” on Apr 4, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323646604578401633067110420.html ), find that the limit of maturities of three years on purchases of JGBs was designed to avoid views that the BOJ would finance uncontrolled government deficits.

- Seigniorage. The BOJ is pursuing coordination with the government that will take measures to establish “sustainable fiscal structure with a view to ensuring the credibility of fiscal management” (http://www.boj.or.jp/en/announcements/release_2013/k130404a.pdf).

- Diversification of Asset Purchases. The BOJ will engage in transactions of exchange traded funds (ETF) and real estate investment trusts (REITS) and not solely on purchases of JGBs. Purchases of ETFs will be at an annual rate of increase of one trillion yen and purchases of REITS at 30 billion yen.

Table VB-BOJF, Bank of Japan, Forecasts of the Majority of Members of the Policy Board, % Year on Year

| Fiscal Year | Real GDP | CPI All Items Less Fresh Food | Excluding Effects of Consumption Tax Hikes |

| 2013 | |||

| Oct 2013 | +2.6 to +3.0 [+2.7] | +0.6 to +1.0 [+0.7] | |

| Jul 2013 | +2.5 to +3.0 [+2.8] | +0.5 to +0.8 [+0.6] | |

| 2014 | |||

| Oct 2013 | +0.9 to +1.5 [+1.5] | +2.8 to +3.6 [+3.3] | +0.8 to +1.6 [+1.3] |

| Jul 2013 | +0.8 to +1.5 [+1.3] | +2.7 to +3.6 [+3.3] | +0.7 to +1.6 [+1.3] |

| 2015 | |||

| Oct 2013 | +1.3 to +1.8 [+1.5] | +1.6 to +2.9 [+2.6] | +0.9 to +2.2 [+1.9] |

| Jul 2013 | +1.3 to +1.9 [+1.5] | +1.6 to +2.9 [+2.6] | +0.9 to +2.2 [+1.9] |

Figures in brackets are the median of forecasts of Policy Board members

Source: Policy Board, Bank of Japan

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/outlook/gor1310b.pdf

Private-sector activity in Japan expanded with the Markit Composite Output PMI™ Index decreased from 56.0 in Oct, which was the highest reading in the six-year history of the survey, to 54.0 in Nov, (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/84e5de2e85dc4979b44676d284eb3780). Claudia Tillbrooke, Economist at Markit and author of the report, finds that the survey data suggest continuing strong growth of the economy of Japan with strength in new orders for manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/84e5de2e85dc4979b44676d284eb3780). The Markit Business Activity Index of Services decreased from the record of 55.3 in Oct to 51.8 in Nov (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/84e5de2e85dc4979b44676d284eb3780). Claudia Tillbrooke, Economist at Markit and author of the report, finds growth in services with strength in new orders but concern on possible effects of increase of sale taxes (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/84e5de2e85dc4979b44676d284eb3780). The Markit/JMMA Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™), seasonally adjusted, increased from 54.2 in Oct to 55.1 in Oct, which is the highest level since Jul 2006 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/f1337c0c4701495c8d63bc0be72aaa7e). New orders grew at the highest rate in 42 months in anticipation of the increase in the sales tax next year. New export orders increased from Thailand and Hong Kong. Claudia Tillbrooke, Economist at Markit and author of the report, finds improving manufacturing conditions at the highest levels in more 42 months with impulse originating in new orders at home and abroad (http://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/f1337c0c4701495c8d63bc0be72aaa7e).Table JPY provides the country data table for Japan.

Table JPY, Japan, Economic Indicators

| Historical GDP and CPI | 1981-2010 Real GDP Growth and CPI Inflation 1981-2010 |

| Corporate Goods Prices | Nov ∆% 0.1 |

| Consumer Price Index | Nov NSA ∆% 0.0; Nov 12 months NSA ∆% 1.5 |

| Real GDP Growth | IIIQ2013 ∆%: 0.3 on IIQ2013; IIIQ2013 SAAR 1.1; |

| Employment Report | Nov Unemployed 2.49 million Change in unemployed since last year: minus 110 thousand |

| All Industry Indices | Oct month SA ∆% -0.2 Blog 12/22/13 |

| Industrial Production | Nov SA month ∆%: 0.1 |

| Machine Orders | Total Oct ∆% -4.6 Private ∆%: 7.0 Oct ∆% Excluding Volatile Orders 0.6 |

| Tertiary Index | Oct month SA ∆% -0.7 |

| Wholesale and Retail Sales | Nov 12 months: |

| Family Income and Expenditure Survey | Nov 12-month ∆% total nominal consumption 2.1, real 0.2 Blog 12/29/13 |

| Trade Balance | Exports Nov 12 months ∆%: 18.4 Imports Nov 12 months ∆% 21.1 Blog 12/22/13 |

Links to blog comments in Table JPY:

12/22/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html

12/15/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html

11/17/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-unwinding-monetary-policy.html

9/15/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html

8/18/13 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

In Nov 2013, industrial production in Japan increased 0.1 percent and increased 5.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013, as shown in Table VB-1. Decline of 3.1 percent in Jun interrupted four consecutive monthly increases from Feb through May 2013. Another interruption occurred in Aug with decrease of 0.9 percent and decline of 0.4 percent in 12 months. Japan’s industrial production is strengthening with growth of 1.4 percent in Dec 2012, 0.9 percent in Feb 2013, 0.1 percent in Mar 2013, 0.9 percent in Apr 2013, 1.9 percent in May 2013, 3.4 percent in Jul 2013, 1.3 percent in Sep 2013 and 1.0 percent in Oct 2013. Industrial production increased 0.1 percent in Nov 2013. Growth in 12 months improved from minus 10.1 percent in Feb 2013 to 5.0 percent in Nov 2013. Industrial production fell 21.9 percent in 2009 after falling 3.4 percent in 2008 but recovered by 15.6 percent in 2010. The annual average in calendar year 2011 fell 2.8 percent largely because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Industrial production increased 0.6 percent in 2012.

Table VB-1, Japan, Industrial Production ∆%

| ∆% Month SA | ∆% 12 Months NSA | |

| Nov 2013 | 0.1 | 5.0 |

| Oct | 1.0 | 5.4 |

| Sep | 1.3 | 5.1 |

| Aug | -0.9 | -0.4 |

| Jul | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Jun | -3.1 | -4.6 |

| May | 1.9 | -1.1 |

| Apr | 0.9 | -3.4 |

| Mar | 0.1 | -7.2 |

| Feb | 0.9 | -10.1 |

| Jan | -0.6 | -6.0 |

| Dec 2012 | 1.4 | -7.6 |

| Nov | -1.0 | -5.5 |

| Oct | 0.3 | -4.7 |

| Sep | -2.2 | -7.6 |

| Aug | -1.4 | -4.1 |

| Jul | -0.5 | 0.1 |

| Jun | -0.8 | -0.6 |

| May | -1.8 | 7.6 |

| Apr | -0.5 | 15.1 |

| Mar | 0.2 | 16.6 |

| Calendar Year | ||

| 2012 | 0.6 | |

| 2011 | -2.8 | |

| 2010 | 15.6 |

Source: Japan, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/statistics/index.html

The employment report for Japan in Nov 2013 is in Table VB-2. The rate of unemployment seasonally adjusted decreased to 4.2 percent in Sep 2012 from 4.3 percent in Jul 2012 and remained at 4.2 percent in Oct 2012, declining to 4.1 percent in Nov 2012, increasing to 4.2 percent in Dec 2012, stabilizing at 4.2 percent in Jan 2013 and increasing to 4.3 percent in Feb 2013. The seasonally adjusted rate of unemployment fell to 4.1 percent in Apr and May 2013. The rate of unemployment not seasonally adjusted stood at 4.1 percent in Apr 2013 and 0.3 percentage points lower from a year earlier. The rate of unemployment fell to 3.9 percent in Jun 2013 seasonally and not seasonally adjusted. In Jul 2013, the rate of unemployment fell to 3.8 percent seasonally adjusted and remained at 3.9 percent not seasonally adjusted. The rate of unemployment rose to 4.1 percent in Aug 2013 and fell to 4.0 percent seasonally adjusted in Sep 2013. The rate of unemployment stabilized at 4.0 percent in Oct 2013 and 4.0 percent in Nov 2013. The employment rate stood at 57.5 percent in Nov 2013 and increased 0.8 percentage points from a year earlier.

Table VB-2, Japan, Employment Report Sep 2013

| Nov 2013 Unemployed | 2.49 million |

| Change since last year | -110 thousand; ∆% –4.2 |

| Unemployment rate | 4.0% SA 0.0; NSA 3.8%, -0.2 from earlier year |

| Population ≥ 15 years | 110.89 million |

| Change since last year | ∆% -0.1 |

| Labor Force | 66.20 million |

| Change since last year | ∆% 1.0 |

| Employed | 63.71 million |

| Change since last year | ∆% 1.2 |

| Labor force participation rate | 59.7 |

| Change since last year | 0.6 |

| Employment rate | 57.5% |

| Change since last year | 0.8 |

Source: Japan, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/results/month/index.htm

Chart VB-1 of Japan’s Statistics Bureau at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications provides the unemployment rate of Japan from 2010 to 2013. The sharp decline in Sep 2011 was the best reading in 2011 but the rate increased in the final quarter of the year, declining in Feb 2012 and stabilizing in Mar 2012 but increasing to 4.6 percent in Apr 2012 and declining again to 4.4 percent in May 2012 and 4.3 percent in both Jun and Jul 2012 with further decline to 4.2 percent in Aug, Sep and Oct 2012, 4.1 percent in Nov 2012, 4.2 percent in Dec 2012, 4.2 percent in Jan 2013, 4.3 percent in Feb 2013 and 4.1 percent in Mar-May 2013. The rate of unemployment fell to 3.9 percent in Jun 2013 and 3.8 percent in Jul 2013. The rate of unemployment rose to 4.1 percent in Aug 2013, falling to 4.0 percent in Sep 2013. The rate of unemployment stabilized at 4.0 percent in Oct 2013 and 4.0 percent in Nov 2013.

Chart VB-1, Japan, Unemployment Rate, Seasonally Adjusted

Source: Japan, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/results/month/index.htm

During the “lost decade” of the 1990s from 1991 to 2002 (Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 82-3), Japan’s GDP grew at the average yearly rate of 1.0 percent, the CPI at 0.1 percent and the implicit deflator at minus 0.8 percent. Japan’s growth rate from the mid 1970s to 1992 was 4 percent (Ito 2004). Table VB-3 provides Japan’s rates of unemployment, participation in labor force and employment for 1968, 1975, 1980 and 1985 and yearly from 1990 to 2012. The rate of unemployment jumped from 2.1 percent in 1991 to 5.4 percent in 2002, which was a year of global economic weakness. The participation rate dropped from 64.0 percent in 1992 to 61.2 percent in 2002 and the employment rate fell from 62.4 percent in 1992 to 57.9 percent in 2002. The rate of unemployment rose from 3.9 percent in 2007 to 5.1 percent in 2010, falling to 4.6 percent in 2011 and 4.3 percent in 2012, while the participation rate fell from 60.4 percent to 59.6 percent, falling to 59.3 percent in 2011 and 59.1 in 2012. The employment rate fell from 58.1 percent to 56.6 percent in 2010 and 56.5 percent in 2011 and 2012. The global recession adversely affected labor markets in advanced economies.

Table VB-3, Japan, Rates of Unemployment, Participation in Labor Force and Employment, %

| Participation | Employment Rate | Unemployment Rate | |

| 1953 | 70.0 | 68.6 | 1.9 |

| 1960 | 69.2 | 68.0 | 1.7 |

| 1965 | 65.7 | 64.9 | 1.2 |

| 1970 | 65.4 | 64.6 | 1.1 |

| 1975 | 63.0 | 61.9 | 1.9 |

| 1980 | 63.3 | 62.0 | 2.0 |

| 1985 | 63.0 | 61.4 | 2.6 |

| 1990 | 63.3 | 61.9 | 2.1 |

| 1991 | 63.8 | 62.4 | 2.1 |

| 1992 | 64.0 | 62.6 | 2.2 |

| 1993 | 63.8 | 62.2 | 2.5 |

| 1994 | 63.6 | 61.8 | 2.9 |

| 1995 | 63.4 | 61.4 | 3.2 |

| 1996 | 63.5 | 61.4 | 3.4 |

| 1997 | 63.7 | 61.5 | 3.4 |

| 1998 | 63.3 | 60.7 | 4.1 |

| 1999 | 62.9 | 59.9 | 4.7 |

| 2000 | 62.4 | 59.5 | 4.7 |

| 2001 | 62.0 | 58.9 | 5.0 |

| 2002 | 61.2 | 57.9 | 5.4 |

| 2003 | 60.8 | 57.6 | 5.3 |

| 2004 | 60.4 | 57.6 | 4.7 |

| 2005 | 60.4 | 57.7 | 4.4 |

| 2006 | 60.4 | 57.9 | 4.1 |

| 2007 | 60.4 | 58.1 | 3.9 |

| 2008 | 60.2 | 57.8 | 4.0 |

| 2009 | 59.9 | 56.9 | 5.1 |

| 2010 | 59.6 | 56.6 | 5.1 |

| 2011 | 59.3 | 56.5 | 4.6 |

| 2012 | 59.1 | 56.5 | 4.3 |

Source: Japan, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/results/month/index.htm

The survey of household income and consumption of Japan in Table VB-4 is showing noticeable improvement in recent months relative to earlier months. Table VB-4 shows growth of nominal consumption of 2.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013 and 0.2 percent in real terms. There are multiple segments of increasing real consumption: housing increasing 3.5 percent in nominal terms and 3.7 percent in real terms and transportation/communications increasing 1.2 percent in real terms and 3.5 percent in nominal terms. Clothing and footwear decreased 0.5 percent in nominal terms and 1.1 percent in real terms. Education decreased 14.2 percent in real terms and 13.6 percent in nominal terms. Fuel, light and water charges increased 4.8 percent in nominal terms and decreased 0.9 percent in real terms. Real household income decreased 1.1 percent; real disposable income decreased 1.4 percent; and real consumption expenditures decreased 1.6 percent.

Table VB-4, Japan, Family Income and Expenditure Survey, 12-month ∆% Relative to a Year Earlier

| Nov 2013 | Nominal | Real |

| Households of Two or More Persons | ||

| Total Consumption | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| Excluding Housing, Vehicles & Remittance | -1.2 | |

| Food | 3.8 | 1.9 |

| Housing | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Fuel, Light & Water Charges | 4.8 | -0.9 |

| Furniture & Household Utensils | 5.3 | 5.5 |

| Clothing & Footwear | -0.5 | -1.1 |

| Medical Care | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Transport and Communications | 3.5 | 1.2 |

| Education | -13.6 | -14.2 |

| Culture & Recreation | 2.7 | 1.5 |

| Other Consumption Expenditures | 0.4 | -1.5* |

| Workers’ Households | ||

| Income | 0.8 | -1.1 |

| Disposable Income | 0.5 | -1.4 |

| Consumption Expenditures | 0.3 | -1.6 |

*Real: nominal deflated by CPI excluding imputed rent

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau, Director General for Policy Planning and Statistical Research and Training Institute

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kakei/156.htm

Chart VB-2 of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication provides year-on-year change of real consumption expenditures. There is improvement followed by deterioration in the final segment with wide oscillations. There was deterioration in Nov 2011, renewed strength in Dec 2011, another decline in Jan 2012 and increase in Feb and Mar 2012 with stabilization in Apr and May 2012 but sharp decline into Jun 2012. Recovery in Jul and Aug 2012 was interrupted in Sep-Oct 2012 and new increases in Nov 2012, Jan 2013, Feb 2013, Mar 2013 and Apr 2013 (http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kakei/156.htm). Total consumption decreased 1.6 percent in real terms in May 2013 and decreased 1.9 percent in nominal terms relative to a year earlier. Real consumption fell 0.4 percent in Jun 2013 and nominal consumption declined 0.1 percent. Consumption rebounded in Jul 2013 with increase of real consumption by 0.1 percent and nominal consumption by 1.0 percent. In Aug 2013, real consumption fell 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier and 0.5 percent in nominal terms. There was marked improvement in Sep 2013 with growth of nominal consumption of 5.2 percent in 12 months and 3.7 percent in real consumption. Nominal consumption increased 2.1 in Nov 2013 and real consumption increased 0.2 percent.

Chart VB-2, Japan, Real Percentage Change of Consumption Year-on-Year

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau, Director General for Policy Planning and Statistical Research and Training Institute

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kakei/156.htm