Tapering Quantitative Easing, Mediocre and Decelerating US Economic Growth, World Inflation Waves, Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits and Fiscal Imbalance, Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates, Theory and Reality of Secular Stagnation and Productivity Growth, US Industrial Production, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013

Executive Summary

I Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IA2 Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits

II World Inflation Waves

IIA Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy

IB1 Theory

IB2 Policy

IB3 Evidence

IB4 Unwinding Strategy

IIB United States Inflation

IIC Long-term US Inflation

IID Current US Inflation

IIE Theory and Reality of Economic History and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

IIF United States Industrial Production and External and Fiscal Imbalances

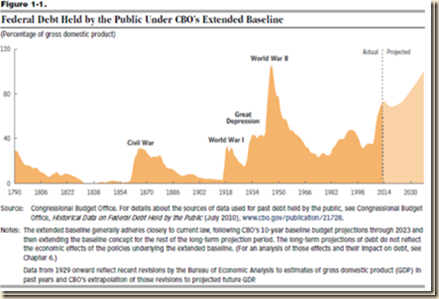

IIA Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits and Fiscal Imbalance Threatening Risk Premium on Treasury Securities

IIA1 United States Unsustainable Deficit/Debt

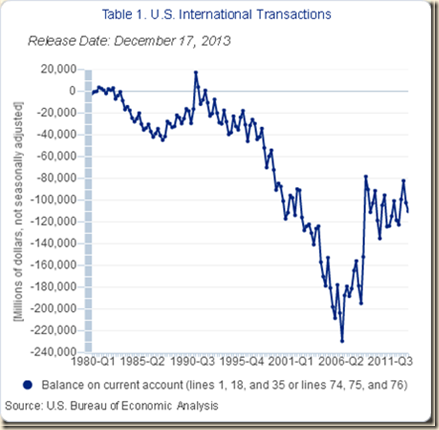

IIA2 Unresolved US Balance of Payments Deficits

IIF United States Industrial Production

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

ID Current US Inflation. Consumer price inflation has fluctuated in recent months. Table I-3 provides 12-month consumer price inflation in Nov 2013 and annual equivalent percentage changes for the months of Sep-Nov 2013 of the CPI and major segments. The final column provides inflation from Oct 2013 to Nov 2013. CPI inflation in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013 reached 1.2 percent, the annual equivalent rate Sep to Nov 2013 was 0.4 percent in the new episode of reversing carry trades from zero interest rates to commodities exposures and the monthly inflation rate of 0.0 percent annualizes at 0.0 percent with oscillating carry trades at the margin. These inflation rates fluctuate in accordance with inducement of risk appetite or frustration by risk aversion of carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures. At the margin, the decline in commodity prices in sharp recent risk aversion in commodities markets caused lower inflation worldwide (with return in some countries in Dec 2012 and Jan-Feb 2013) that followed a jump in Aug-Sep 2012 because of the relaxed risk aversion resulting from the bond-buying program of the European Central Bank or Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) (http://www.ecb.int/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120906_1.en.html). Carry trades moved away from commodities into stocks with resulting weaker commodity prices and stronger equity valuations. There is reversal of exposures in commodities but with preferences of equities by investors. With zero interest rates, commodity prices would increase again in an environment of risk appetite. Excluding food and energy, CPI inflation was 1.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013 and 1.6 percent in annual equivalent in Sep to Nov 2013. There is no deflation in the US economy that could justify further quantitative easing, which is now open-ended or forever with zero interest rates and potential tapering bond-buying by the central bank, or QE→∞, even if the economy grows back to potential. Financial repression of zero interest rates is now intended as a permanent distortion of resource allocation by clouding risk/return decisions, preventing the economy from expanding along its optimal growth path. Consumer food prices in the US have risen 1.2 percent in 12 months ending in Nov 2013 and at 0.8 percent in annual equivalent in Sep to Nov 2013. Monetary policies stimulating carry trades of commodities futures that increase prices of food constitute a highly regressive tax on lower income families for whom food is a major portion of the consumption basket especially with wage increases below inflation in a recovery without hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html) and without jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-mediocre.htm). Energy consumer prices decreased 2.4 percent in 12 months, decreased 7.4 percent in annual equivalent in Sep to Nov 2013 and decreased 1.0 percent in Nov 2013 or at minus 11.4 percent in annual equivalent. Waves of inflation are induced by carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures, which are unwound and repositioned during alternating risk aversion and risk appetite originating in the European debt crisis and increasingly in growth and politics in China. For lower income families, food and energy are a major part of the family budget. Inflation is not persistently low or threatening deflation in annual equivalent in Sep to Nov 2013 in any of the categories in Table I-2 but simply reflecting waves of inflation originating in carry trades. Carry trades from zero interest rates induce commodity futures positions with episodes of risk aversion causing fluctuations determine an upward trend of prices.

Table I-3, US, Consumer Price Index Percentage Changes 12 months NSA and Annual Equivalent ∆%

| % RI | ∆% 12 Months Nov 2013/Nov | ∆% Annual Equivalent Sep 2013 to Nov 2013 SA | ∆% Nov 2013/Oct 2013 SA | |

| CPI All Items | 100.000 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 76.179 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.2 |

| Food | 14.218 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Food at Home | 8.508 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Food Away from Home | 5.710 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| Energy | 9.603 | -2.4 | -7.4 | -1.0 |

| Gasoline | 5.270 | -5.8 | -14.0 | -1.6 |

| Electricity | 2.926 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 0.3 |

| Commodities less Food and Energy | 19.431 | -0.2 | -1.2 | -0.1 |

| New Vehicles | 3.142 | 0.6 | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| Used Cars and Trucks | 1.877 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.1 |

| Medical Care Commodities | 1.710 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| Apparel | 3.654 | -0.1 | -5.5 | -0.4 |

| Services Less Energy Services | 56.748 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| Shelter | 31.797 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| Rent of Primary Residence | 6.577 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| Owner’s Equivalent Rent of Residences | 24.089 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.3 |

| Transportation Services | 5.847 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 0.3 |

| Medical Care Services | 5.491 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

% RI: Percent Relative Importance

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

The weights of the CPI, US city average for all urban consumers representing about 87 percent of the US population (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiovrvw.htm#item1), are shown in Table I-4 with the BLS update for Dec 2012 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiri2012.pdf). Housing has a weight of 41.021 percent. The combined weight of housing and transportation is 57.867 percent or more than one-half of consumer expenditures of all urban consumers. The combined weight of housing, transportation and food and beverages is 73.128 percent of the US CPI. Table I-3 provides relative importance of key items in Nov 2013.

Table I-4, US, Relative Importance, 2009-2010 Weights, of Components in the Consumer Price Index, US City Average, Dec 2012

| All Items | 100.000 |

| Food and Beverages | 15.261 |

| Food | 14.312 |

| Food at home | 8.898 |

| Food away from home | 5.713 |

| Housing | 41.021 |

| Shelter | 31.681 |

| Rent of primary residence | 6.545 |

| Owners’ equivalent rent | 22.622 |

| Apparel | 3.564 |

| Transportation | 16.846 |

| Private Transportation | 15.657 |

| New vehicles | 3.189 |

| Used cars and trucks | 1.844 |

| Motor fuel | 5.462 |

| Gasoline | 5.274 |

| Medical Care | 7.163 |

| Medical care commodities | 1.714 |

| Medical care services | 5.448 |

| Recreation | 5.990 |

| Education and Communication | 6.779 |

| Other Goods and Services | 3.376 |

Refers to all urban consumers, covering approximately 87 percent of the US population (see http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiovrvw.htm#item1). Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiri2011.pdf http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiriar.htm http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiri2012.pdf

Chart I-18 provides the US consumer price index for housing from 2001 to 2013. Housing prices rose sharply during the decade until the bump of the global recession and increased again in 2011-2012 with some stabilization. The CPI excluding housing would likely show much higher inflation. The commodity carry trades resulting from unconventional monetary policy have compressed income remaining after paying for indispensable shelter.

Chart I-18, US, Consumer Price Index, Housing, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart I-19 provides 12-month percentage changes of the housing CPI. Percentage changes collapsed during the global recession but have been rising into positive territory in 2011 and 2012-2013 but with the rate declining and then increasing.

Chart I-19, US, Consumer Price Index, Housing, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

There have been waves of consumer price inflation in the US in 2011 and into 2012 (Section IA and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html) that are illustrated in Table I-5. The first wave occurred in Jan-Apr 2011 and was caused by the carry trade of commodity prices induced by unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates. Cheap money at zero opportunity cost in environment of risk appetite was channeled into financial risk assets, causing increases in commodity prices. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all-items CPI in Jan-Apr 2011 was 4.6 percent and the CPI excluding food and energy increased at annual equivalent rate of 2.1 percent. The second wave occurred during the collapse of the carry trade from zero interest rates to exposures in commodity futures because of risk aversion in financial markets created by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all-items CPI dropped to 3.0 percent in May-Jun 2011 while the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy increased at 3.0 percent. In the third wave in Jul-Sep 2011, annual equivalent CPI inflation rose to 3.3 percent while the core CPI increased at 2.0 percent. The fourth wave occurred in the form of increase of the CPI all-items annual equivalent rate to 0.6 percent in Oct-Nov 2011 with the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy remaining at 2.4 percent. The fifth wave occurred in Dec 2011 to Jan 2012 with annual equivalent headline inflation of 1.2 percent and core inflation of 2.4 percent. In the sixth wave, headline CPI inflation increased at annual equivalent 3.7 percent in Feb-Mar 2012 and core CPI inflation at 1.8 percent but including Apr 2012, the annual equivalent inflation of the headline CPI was 2.4 percent in Feb-Apr 2012 and 2.0 percent for the core CPI. The seventh wave in May-Jul occurred with annual equivalent inflation of 0.0 percent for the headline CPI in May-Jul 2012 and 2.0 percent for the core CPI. The eighth wave is with annual equivalent inflation of 6.2 percent in Aug-Sep 2012 but 4.9 percent including Oct. In the ninth wave, annual equivalent inflation in Nov 2012 was minus 2.4 percent under the new shock of risk aversion and 0.0 percent in Dec 2012 with annual equivalent of minus 0.8 percent in Nov 2012-Jan 2013 and 2.0 percent for the core CPI. In the tenth wave, annual equivalent of headline CPI was 8.7 percent in Feb 2013 and 2.4 percent for the core CPI. In the eleventh wave, annual equivalent was minus 3.5 percent in Mar-Apr 2013 and 1.2 percent for the core index. In the twelfth wave, annual equivalent inflation was 2.7 percent in May-Sep 2013 and 1.9 percent for the core CPI. In the thirteenth wave, annual equivalent CPI inflation in Oct-Nov 2013 was minus 0.6 percent and 1.8 percent for the core CPI. The conclusion is that inflation accelerates and decelerates in unpredictable fashion because of shocks or risk aversion and portfolio reallocations in carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity derivatives.

Table I-5, US, Headline and Core CPI Inflation Monthly SA and 12 Months NSA ∆%

| All Items SA Month | All Items NSA 12 month | Core SA | Core NSA | |

| Nov 2013 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Oct | -0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Nov | -0.6 | 1.8 | ||

| Sep | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Jun | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| May | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% May-Sep | 2.7 | 1.9 | ||

| Apr | -0.4 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Mar | -0.2 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| AE ∆% Mar-Apr | -3.5 | 1.2 | ||

| Feb | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| AE ∆% Feb | 8.7 | 2.4 | ||

| Jan | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Dec 2012 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| Nov | -0.2 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| AE ∆% Nov-Jan | -0.8 | 2.0 | ||

| Oct | 0.2 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Sep | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Aug | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Oct | 4.9 | 2.0 | ||

| Jul | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 2.2 |

| May | -0.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Apr | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Mar | 0.3 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Feb | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Apr | 2.4 | 2.0 | ||

| Jan | 0.2 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Dec 2011 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 2.2 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Jan | 1.2 | 2.4 | ||

| Nov | 0.1 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 2.2 |

| Oct | 0.0 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Nov | 0.6 | 2.4 | ||

| Sep | 0.3 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Aug | 0.3 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Sep | 3.3 | 2.0 | ||

| Jun | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| May | 0.4 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | 3.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Apr | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Mar | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Feb | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Jan | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 4.6 | 2.1 | ||

| Dec 2010 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Nov | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Oct | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Sep | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Aug | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Jun | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| May | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Apr | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Mar | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Feb | -0.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jan | 0.1 | 2.6 | -0.1 | 1.6 |

Note: Core: excluding food and energy; AE: annual equivalent

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The behavior of the US consumer price index NSA from 2001 to 2013 is provided in Chart I-20. Inflation in the US is very dynamic without deflation risks that would justify symmetric inflation targets. The hump in 2008 originated in the carry trade from interest rates dropping to zero into commodity futures. There is no other explanation for the increase of the Cushing OK Crude Oil Future Contract 1 from $55.64/barrel on Jan 9, 2007 to $145.29/barrel on July 3, 2008 during deep global recession, collapsing under a panic of flight into government obligations and the US dollar to $37.51/barrel on Feb 13, 2009 and then rising by carry trades to $113.93/barrel on Apr 29, 2012, collapsing again and then recovering again to $105.23/barrel, all during mediocre economic recovery with peaks and troughs influenced by bouts of risk appetite and risk aversion (data from the US Energy Information Administration EIA, http://www.eia.gov/). The unwinding of the carry trade with the TARP announcement of toxic assets in banks channeled cheap money into government obligations (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009).

Chart I-20, US, Consumer Price Index, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Chart I-21 provides 12-month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 2001 to 2013. There was no deflation or threat of deflation from 2008 into 2009. Commodity prices collapsed during the panic of toxic assets in banks. When stress tests in 2009 revealed US bank balance sheets in much stronger position, cheap money at zero opportunity cost exited government obligations and flowed into carry trades of risk financial assets. Increases in commodity prices drove again the all items CPI with interruptions during risk aversion originating in multiple fears but especially from the sovereign debt crisis of Europe.

Chart I-21, US, Consumer Price Index, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

The trend of increase of the consumer price index excluding food and energy in Chart I-22 does not reveal any threat of deflation that would justify symmetric inflation targets. There are mild oscillations in a neat upward trend.

Chart I-22, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Chart I-23 provides 12-month percentage change of the consumer price index excluding food and energy. Past-year rates of inflation fell toward 1 percent from 2001 into 2003 because of the recession and the decline of commodity prices beginning before the recession with declines of real oil prices. Near zero interest rates with fed funds at 1 percent between Jun 2003 and Jun 2004 stimulated carry trades of all types, including in buying homes with subprime mortgages in expectation that low interest rates forever would increase home prices permanently, creating the equity that would permit the conversion of subprime mortgages into creditworthy mortgages (Gorton 2009EFM; see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html). Inflation rose and then collapsed during the unwinding of carry trades and the housing debacle of the global recession. Carry trades into 2011 and 2012 gave a new impulse to CPI inflation, all items and core. Symmetric inflation targets destabilize the economy by encouraging hunts for yields that inflate and deflate financial assets, obscuring risk/return decisions on production, investment, consumption and hiring.

Chart I-23, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Headline and core producer price indexes are in Table I-6. The headline PPI SA decreased 0.1 percent in Nov 2013 and increased 0.7 percent NSA in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. The core PPI SA increased 0.1 percent in Nov 2013 and rose 1.3 percent in 12 months. Analysis of annual equivalent rates of change shows inflation waves similar to those worldwide. In the first wave, the absence of risk aversion from the sovereign risk crisis in Europe motivated the carry trade from zero interest rates into commodity futures that caused the average equivalent rate of 10.0 percent in the headline PPI in Jan-Apr 2011 and 4.0 percent in the core PPI. In the second wave, commodity futures prices collapsed in Jun 2011 with the return of risk aversion originating in the sovereign risk crisis of Europe. The annual equivalent rate of headline PPI inflation collapsed to 1.8 percent in May-Jun 2011 but the core annual equivalent inflation rate was higher at 2.4 percent. In the third wave, headline PPI inflation resuscitated with annual equivalent at 4.9 percent in Jul-Sep 2011 and core PPI inflation at 3.7 percent. Core PPI inflation was persistent throughout 2011, jumping from annual equivalent at 1.5 percent in the first four months of 2010 to 3.0 percent in 12 months ending in Dec 2011. Unconventional monetary policy is based on the proposition that core rates reflect more fundamental inflation and are thus better predictors of the future. In practice, the relation of core and headline inflation is as difficult to predict as future inflation (see IIID Supply Shocks in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html). In the fourth wave, risk aversion originating in the lack of resolution of the European debt crisis caused unwinding of carry trades with annual equivalent headline PPI inflation of 0.6 percent in Oct-Nov 2011 and 1.8 percent in the core annual equivalent. In the fifth wave from Dec 2011 to Jan 2012, annual equivalent inflation was 0.0 percent for the headline index but 4.3 percent for the core index excluding food and energy. In the sixth wave, annual equivalent inflation in Feb-Mar 2012 was 2.4 percent for the headline PPI and 2.4 percent for the core. In the seventh wave, renewed risk aversion caused reversal of carry trades into commodity exposures with annual equivalent headline inflation of minus 4.7 percent in Apr-May 2012 while core PPI inflation was at annual equivalent 1.2 percent. In the eighth wave, annual equivalent inflation returned at 3.0 percent in Jun-Jul 2012 and 4.3 percent for the core index. In the ninth wave, relaxed risk aversion because of the announcement of the impaired bond buying program or Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) of the European Central Bank (http://www.ecb.int/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120906_1.en.html) induced carry trades that drove annual equivalent inflation of producer prices of the United States at 12.7 percent in Aug-Sep 2012 and 0.6 percent in the core index. In the tenth wave, renewed risk aversion caused annual equivalent inflation of minus 3.2 percent in Oct 2011-Dec 2012 in the headline index and 1.2 percent in the core index. In the eleventh wave, annual equivalent inflation was 5.5 percent in the headline index in Jan-Feb 2013 and 1.8 percent in the core index. In the twelfth wave, annual equivalent was minus 7.5 percent in Mar-Apr 2012 and 1.8 percent for the core index. In the thirteenth wave, annual equivalent inflation returned at 5.2 percent in May-Aug 2013 and 0.9 percent in the core index. In the fourteenth wave, portfolio reallocations away from commodities and into equities reversed commodity carry trade with annual equivalent inflation of minus 1.6 percent in Sep-Nov 2013 in the headline PPI and 1.6 percent in the core. It is almost impossible to forecast PPI inflation and its relation to CPI inflation. “Inflation surprise” by monetary policy could be proposed to climb along a downward sloping Phillips curve, resulting in higher inflation but lower unemployment (see Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983 and past comments of this blog http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html). The architects of monetary policy would require superior inflation forecasting ability compared to forecasting naivety by everybody else. In practice, we are all naïve in forecasting inflation and other economic variables and events.

Table I-6, US, Headline and Core PPI Inflation Monthly SA and 12-Month NSA ∆%

| Finished | Finished | Finished Core SA | Finished Core NSA | |

| Nov 2013 | -0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Oct | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Sep | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| AE ∆% Sep-Nov | -1.6 | 1.6 | ||

| Aug | 0.4 | 1.4 | -0.1 | 1.1 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jun | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| May | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% May-Aug | 5.2 | 0.9 | ||

| Apr | -0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Mar | -0.6 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% Mar-Apr | -7.5 | 1.8 | ||

| Feb | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| Jan | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Feb | 5.5 | 1.8 | ||

| Dec 2012 | -0.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| Nov | -0.5 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| Oct | -0.2 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Dec | -3.2 | 1.2 | ||

| Sep | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 2.4 |

| Aug | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Sep | 12.7 | 0.6 | ||

| Jul | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.6 |

| AE ∆% Jun-Jul | 3.0 | 4.3 | ||

| May | -0.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| Apr | -0.2 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| AE ∆% Apr-May | -4.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Mar | 0.1 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 2.9 |

| Feb | 0.3 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 3.1 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Mar | 2.4 | 2.4 | ||

| Jan | 0.1 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 3.1 |

| Dec 2011 | -0.1 | 4.7 | 0.3 | 3.0 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Jan | 0.0 | 4.3 | ||

| Nov | 0.4 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 3.0 |

| Oct | -0.3 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 2.9 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Nov | 0.6 | 1.8 | ||

| Sep | 0.9 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| Aug | -0.3 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| Jul | 0.6 | 7.1 | 0.5 | 2.7 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Sep | 4.9 | 3.7 | ||

| Jun | -0.1 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| May | 0.4 | 7.1 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | 1.8 | 2.4 | ||

| Apr | 0.7 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 5.6 | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| Feb | 1.1 | 5.4 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| Jan | 0.7 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 10.0 | 4.0 | ||

| Dec 2010 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Nov | 0.6 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Oct | 0.7 | 4.3 | -0.1 | 1.6 |

| Sep | 0.4 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Aug | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 |

| Jun | -0.3 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| May | 0.0 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Apr | -0.2 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Feb | -0.7 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

Note: Core: excluding food and energy; AE: annual equivalent

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The US producer price index NSA from 2000 to 2013 is shown in Chart I-24. There are two episodes of decline of the PPI during recessions in 2001 and in 2008. Barsky and Kilian (2004) consider the 2001 episode as one in which real oil prices were declining when recession began. Recession and the fall of commodity prices instead of generalized deflation explain the behavior of US inflation in 2008.

Chart I-24, US, Producer Price Index, NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

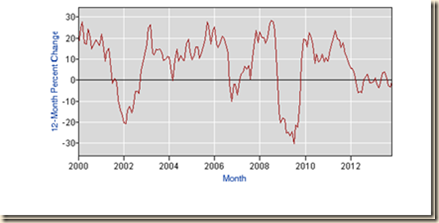

Twelve-month percentage changes of the PPI NSA from 2000 to 2013 are shown in Chart I-25. It may be possible to forecast trends a few months in the future under adaptive expectations but turning points are almost impossible to anticipate especially when related to fluctuations of commodity prices in response to risk aversion. In a sense, monetary policy has been tied to behavior of the PPI in the negative 12-month rates in 2001 to 2003 and then again in 2009 to 2010. Monetary policy following deflation fears caused by commodity price fluctuations would introduce significant volatility and risks in financial markets and eventually in consumption and investment.

Chart I-25, US, Producer Price Index, 12-Month Percentage Change NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The US PPI excluding food and energy from 2000 to 2013 is shown in Chart I-26. There is here again a smooth trend of inflation instead of prolonged deflation as in Japan.

Chart I-26, US, Producer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Twelve-month percentage changes of the producer price index excluding food and energy are shown in Chart I-27. Fluctuations replicate those in the headline PPI. There is an evident trend of increase of 12 months rates of core PPI inflation in 2011 but lower rates in 2012-2013.

Chart I-27, US, Producer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The US producer price index of energy goods from 2000 to 2013 is in Chart I-28. There is a clear upward trend with fluctuations that would not occur under persistent deflation.

Chart I-28, US, Producer Price Index Finished Energy Goods, NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart I-29 provides 12-month percentage changes of the producer price index of energy goods from 2000 to 2013. Barsky and Kilian (2004) relate the episode of declining prices of energy goods in 2001 to 2002 to the analysis of decline of real oil prices. Interest rates dropping to zero during the global recession in 2008 induced carry trades that explain the rise of the PPI of energy goods toward 30 percent. Bouts of risk aversion with policy interest rates held close to zero explain the fluctuations in the 12-month rates of the PPI of energy goods in the expansion phase of the economy. Symmetric inflation targets induce significant instability in inflation and interest rates with adverse effects on financial markets and the overall economy.

Chart I-29, US, Producer Price Index Energy Goods, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table I-7, CPI All Items, CPI Core and CPI Housing, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA 2001-2013

| Nov | CPI All Items | CPI Core ex Food and Energy | CPI Housing |

| 2013 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| 2012 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| 2011 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| 2010 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| 2009 | 1.8 | 1.7 | -0.3 |

| 2008 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| 2007 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| 2006 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 3.0 |

| 2005 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 4.0 |

| 2004 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 3.1 |

| 2003 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.2 |

| 2002 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| 2001 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Chart IIA2-1 provides prices of total US imports 2001-2013. Prices fell during the contraction of 2001. Import price inflation accelerated after unconventional monetary policy of near zero interest rates in 2003-2004 and quantitative easing by withdrawing supply with the suspension of 30-year Treasury bond auctions. Slow pace of adjusting fed funds rates from 1 percent by increments of 25 basis points in 17 consecutive meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) between Jun 2004 and Jun 2006 continued to give impetus to carry trades. The reduction of fed funds rates toward zero in 2008 fueled a spectacular global hunt for yields that caused commodity price inflation in the middle of a global recession. After risk aversion in 2009 because of the announcement of TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) creating anxiety on “toxic assets” in bank balance sheets (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009), prices collapsed because of unwinding carry trades. Renewed price increases returned with zero interest rates and quantitative easing. Monetary policy impulses in massive doses have driven inflation and valuation of risk financial assets in wide fluctuations over a decade.

Chart IIA2-1, US, Prices of Total US Imports 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-2 provides 12-month percentage changes of prices of total US imports from 2001 to 2013. The only plausible explanation for the wide oscillations is by the carry trade originating in unconventional monetary policy. Import prices jumped in 2008 during deep and protracted global recession driven by carry trades from zero interest rates to long, leveraged positions in commodity futures. Carry trades were unwound during the financial panic in the final quarter of 2008 that resulted in flight to government obligations. Import prices jumped again in 2009 with subdued risk aversion because US banks did not have unsustainable toxic assets. Import prices then fluctuated as carry trades were resumed during periods of risk appetite and unwound during risk aversion resulting from the European debt crisis.

Chart IIA2-2, US, Prices of Total US Imports, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-3 provides prices of US imports from 1982 to 2013. There is no similar episode to that of the increase of commodity prices in 2008 during a protracted and deep global recession with subsequent collapse during a flight into government obligations. Trade prices have been driven by carry trades created by unconventional monetary policy in the past decade.

Chart IIA2-3, US, Prices of Total US Imports, 2001=100, 1982-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

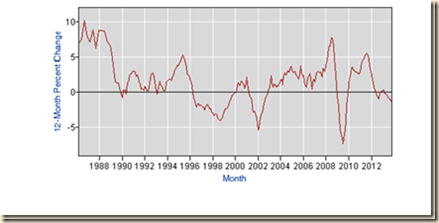

Chart IIA2-4 provides 12-month percentage changes of US total imports from 1982 to 2013. There have not been wide consecutive oscillations as the ones during the global recession of IVQ2007 to IIQ2009.

Chart IIA2-4, US, Prices of Total US Imports, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1982-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-5 provides the index of US export prices from 2001 to 2013. Import and export prices have been driven by impulses of unconventional monetary policy in massive doses. The most recent segment in Chart IIA2-5 shows declining trend resulting from a combination of the world economic slowdown and the decline of commodity prices as carry trade exposures are unwound because of risk aversion to the sovereign debt crisis in Europe and slowdown in the world economy.

Chart IIA2-5, US, Prices of Total US Exports, 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-6 provides prices of US total exports from 1982 to 2013. The rise before the global recession from 2003 to 2008, driven by carry trades, is also unique in the series and is followed by another steep increase after risk aversion moderated in IQ2009.

Chart IIA2-6, US, Prices of Total US Exports, 2001=100, 1982-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-7 provides 12-month percentage changes of total US exports from 1982 to 2013. The uniqueness of the oscillations around the global recession of IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 is clearly revealed.

Chart IIA2-7, US, Prices of Total US Exports, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1982-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Twelve-month percentage changes of US prices of exports and imports are provided in Table IIA2-1. Import prices have been driven since 2003 by unconventional monetary policy of near zero interest rates influencing commodity prices according to moods of risk aversion and portfolio reallocations. In a global recession without risk aversion until the panic of Sep 2008 with flight to government obligations, import prices increased 21.4 percent in the 12 months ending in Jul 2008, 18.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug 2008, 13.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2008, 4.9 percent in the twelve months ending in Oct 2008. Import prices fell 5.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2008 when risk aversion developed in 2008 until mid 2009 (http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm). Import prices rose again sharply in Nov 2010 by 4.1 percent and in Nov 2010 by 10.1 percent in the presence of zero interest rates with relaxed mood of risk aversion until carry trades were unwound in May 2011 and following months as shown by decrease of import prices by 1.4 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2012 and 2.0 percent in Dec 2012 and decrease of 0.3 percent in prices of exports in the 12 months ending in Dec 2012. Import prices increased 15.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2008, fell 14.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2009 and increased 11.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2010. Fluctuations are much sharper in imports because of the high content of oil that as all commodities futures contracts increases sharply with zero interest rates and risk appetite, contracting under risk aversion. There is similar behavior of prices of imports ex fuels, exports and exports ex agricultural goods but less pronounced than for commodity-rich prices dominated by carry trades from zero interest rates. A critical event resulting from unconventional monetary policy driving higher commodity prices by carry trades is the deterioration of the terms of trade, or export prices relative to import prices, that has adversely affected US real income growth relative to what it would have been in the absence of unconventional monetary policy. Europe, Japan and other advanced economies have experienced similar deterioration of their terms of trade. Because of unwinding carry trades of commodity futures because of risk aversion and portfolio reallocations, import prices decreased 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013, export prices decreased 1.2 percent and prices of nonagricultural exports fell 1.6 percent. Imports excluding fuel fell 1.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Nov 2013. At the margin, price changes over the year in world exports and imports are decreasing or increasing moderately because of unwinding carry trades in a temporary mood of risk aversion and relative allocation of asset classes toward equities that reverses exposures in commodity futures.

Table IIA2-1, US, Twelve-Month Percentage Rates of Change of Prices of Exports and Imports

| Imports | Imports Ex Fuels | Exports | Exports Non-Ag | |

| Nov 2013 | -1.5 | -1.2 | -1.6 | -1.0 |

| Nov 2012 | -1.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | -0.3 |

| Nov 2011 | 10.1 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Nov 2010 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 6.5 | 5.1 |

| Nov 2009 | 3.4 | -1.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Nov 2008 | -5.9 | 2.6 | -0.3 | 0.0 |

| Nov 2007 | 12.0 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 4.7 |

| Nov 2006 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| Nov 2005 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 2.6 |

| Nov 2004 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 5.2 |

| Nov 2003 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Nov 2002 | 2.5 | NA | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Nov 2001 | -8.8 | NA | -2.5 | -2.5 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Table IIA2-2 provides 12-month percentage changes of the import price index all commodities from 2001 to 2013. Interest rates moving toward zero during unconventional monetary policy in 2008 induced carry trades into highly leveraged commodity derivatives positions that caused increases in 12-month percentage changes of import prices of around 20 percent. The flight into dollars and Treasury securities by fears of toxic assets in banks in the proposal of TARP (Cochrane and Zingales 2009) caused reversion of carry trades and collapse of commodity futures explaining sharp declines in trade prices in 2009. Twelve-month percentage changes of import prices at the end of 2012 and into 2013 occurred during another bout of risk aversion and portfolio reallocation.

Table IIA2-2, US, Twelve-Month Percentage Changes of Import Price Index All Commodities, 2001-2013

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| 2001 | -0.7 | -0.8 | -2.6 | -4.1 | -4.4 | -5.6 | -7.4 | -8.8 | -9.1 |

| 2002 | -3.6 | -3.7 | -3.6 | -1.7 | -1.3 | -0.4 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 4.2 |

| 2003 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 2004 | 4.6 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 9.0 | 6.7 |

| 2005 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 8.0 |

| 2006 | 5.8 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 1.6 | -1.0 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| 2007 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 9.1 | 12.0 | 10.6 |

| 2008 | 16.9 | 19.1 | 21.3 | 21.4 | 18.1 | 13.1 | 4.9 | -5.9 | -10.1 |

| 2009 | -16.4 | -17.3 | -17.5 | -19.1 | -15.3 | -12.0 | -5.6 | 3.4 | 8.6 |

| 2010 | 11.2 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 5.3 |

| 2011 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 8.5 |

| 2012 | 0.8 | -0.8 | -2.5 | -3.3 | -1.8 | -0.6 | 0.0 | -1.4 | -2.0 |

| 2013 | -2.7 | -1.8 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | -0.7 | -1.6 | -1.5 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

There is finer detail in one-month percentage changes of imports of the US in Table IIA2-3. Carry trades into commodity futures induced by interest rates moving to zero in unconventional monetary policy caused sharp monthly increases in import prices for cumulative increase of 13.8 percent from Mar to Jul 2008 at average rate of 2.6 percent per month or annual equivalent in five months of 36.4 percent (3.1 percent in Mar 2008, 2.8 percent in Apr 2008, 2.8 percent in May 2008, 3.0 percent in Jun 2008 and 1.4 percent in Jul 2008, data from http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm). There is no other explanation for increases in import prices during sharp global recession and contracting world trade. Import prices then fell 23.4 percent from Aug 2008 to Jan 2009 or at the annual equivalent rate of minus 41.4 percent in the flight to US government securities in fear of the need to buy toxic assets from banks in the TARP program (Cochrane and Zingales 2009). Risk aversion during the first sovereign debt crisis of the euro area in May-Jun 2010 caused decline of US import prices at the annual equivalent rate of 11.4 percent. US import prices have been driven by combinations of carry trades induced by unconventional monetary policy and bouts of risk aversion and portfolio reallocation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world.html). US import prices increased 0.5 percent in Jan 2013 and 0.9 percent in Feb 2013 for annual equivalent rate of 8.7 percent, similar to those in national price indexes worldwide, originating in carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures. Import prices fell 0.1 percent in Mar 2013, 0.7 percent in Apr 2013, 0.6 percent in May 2013 and 0.4 percent in Jun 2013. Import prices changed 0.1 percent in Jul 2013, increased 0.4 percent in Aug 2013 and increased 0.3 percent in Sep 2013. Portfolio reallocations into asset classes other than commodities explains declines of import prices by 0.6 percent in Oct 2013 and 0.6 percent in Nov 2013.

Table IIA2-3, US, One-Month Percentage Changes of Import Price Index All Commodities, 2001-2013

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| 2001 | -0.5 | 0.2 | -0.4 | -1.5 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -2.3 | -1.5 | -1.0 |

| 2002 | 1.6 | 0.1 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | -0.9 | 0.6 |

| 2003 | -3.1 | -0.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.0 | -0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 2004 | 0.2 | 1.5 | -0.2 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.6 | -0.3 | -1.4 |

| 2005 | 0.9 | -0.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 0.1 | -1.9 | 0.0 |

| 2006 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | -2.2 | -2.5 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| 2007 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | -0.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 3.2 | -0.2 |

| 2008 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.4 | -3.1 | -3.6 | -6.0 | -7.4 | -4.6 |

| 2009 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | -0.6 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| 2010 | 1.1 | -0.8 | -1.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| 2011 | 2.6 | 0.1 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -0.4 | -0.1 | -0.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| 2012 | -0.1 | -1.5 | -2.3 | -0.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | -0.7 | -0.6 |

| 2013 | -0.7 | -0.6 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | -0.6 | -0.6 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-8 shows the US monthly import price index of all commodities excluding fuels from 2001 to 2013. All curves of nominal values follow the same behavior under the influence of unconventional monetary policy. Zero interest rates without risk aversion result in jumps of nominal values while under strong risk aversion even with zero interest rates there are declines of nominal values.

Chart IIA2-8, US, Import Price Index All Commodities Excluding Fuels, 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-9 provides 12-month percentage changes of the US import price index excluding fuels between 2001 and 2013. There is the same behavior of carry trades driving up without risk aversion and down with risk aversion prices of raw materials, commodities and food in international trade during the global recession of IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 and in previous and subsequent periods.

Chart IIA2-9, US, Import Price Index All Commodities Excluding Fuels, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 2002-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-10 provides the monthly US import price index ex petroleum from 2001 to 2013. Prices including or excluding commodities follow the same fluctuations and trends originating in impulses of unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates.

Chart IIA2-10, US, Import Price Index ex Petroleum, 2001=100, 2000-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-11 provides the US import price index ex petroleum from 1985 to 2013. There is the same unique hump in 2008 caused by carry trades from zero interest rates to prices of commodities and raw materials.

Chart IIA2-11, US, Import Price Index ex Petroleum, 2001=100, 1985-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-12 provides 12-month percentage changes of the import price index ex petroleum from 1986 to 2013. The oscillations caused by the carry trade in increasing prices of commodities and raw materials without risk aversion and subsequently decreasing them during risk aversion are unique.

Chart IIA2-12, US, Import Price Index ex Petroleum, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1986-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-13 of the US Energy Information Administration shows the price of WTI crude oil since the 1980s. Chart IA2-13 captures commodity price shocks during the past decade. The costly mirage of deflation was caused by the decline in oil prices during the recession of 2001. The upward trend after 2003 was promoted by the carry trade from near zero interest rates. The jump above $140/barrel during the global recession in 2008 at $145.29/barrel on Jul 3, 2008, can only be explained by the carry trade promoted by monetary policy of zero fed funds rate. After moderation of risk aversion, the carry trade returned with resulting sharp upward trend of crude prices. Risk aversion resulted in another drop in recent weeks followed by some recovery and renewed deterioration/increase.

Chart IIA2-13, US, Crude Oil Futures Contract

Source: US Energy Information Administration

http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=RCLC1&f=D

The price index of US imports of petroleum and petroleum products in shown in Chart IIA2-14. There is similar behavior of the curves all driven by the same impulses of monetary policy.

Chart IIA2-14, US, Import Price Index of Petroleum and Petroleum Products, 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-15 provides the price index of petroleum and petroleum products from 1982 to 2013. The rise in prices during the global recession in 2008 and the decline after the flight to government obligations is unique in the history of the series. Increases in prices of trade in petroleum and petroleum products were induced by carry trades and declines by unwinding carry trades in flight to government obligations.

Chart IIA2-15, US, Import Price Index of Petroleum and Petroleum Products, 2001=100, 1982-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-16 provides 12-month percentage changes of the price index of US imports of petroleum and petroleum products from 1982 to 2013. There were wider oscillations in this index from 1999 to 2001 (see Barsky and Killian 2004 for an explanation).

Chart IIA2-16, US, Import Price Index of Petroleum and Petroleum Products, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1982-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

The price index of US exports of agricultural commodities is in Chart IIA2-17 from 2001 to 2013. There are similar fluctuations and trends as in all other price index originating in unconventional monetary policy repeated over a decade. The most recent segment in 2011 has declining trend in a new flight from risk resulting from the sovereign debt crisis in Europe followed by declines in Jun 2012 and Nov 2012 with stability/decline in Dec 2012 into 2013.

Chart IIA2-17, US, Exports Price Index of Agricultural Commodities, 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-18 provides the price index of US exports of agricultural commodities from 1982 to 2013. The increase in 2008 in the middle of deep, protracted contraction was induced by unconventional monetary policy. The decline from 2008 into 2009 was caused by unwinding carry trades in a flight to government obligations. The increase into 2011 and current pause were also induced by unconventional monetary policy in waves of increases during relaxed risk aversion and declines during unwinding of positions because of aversion to financial risk.

Chart IIA2-18, US, Exports Price Index of Agricultural Commodities, 2001=100, 1982-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-19 provides 12-month percentage changes of the index of US exports of agricultural commodities from 1986 to 2013. The wide swings in 2008, 2009 and 2011 are only explained by unconventional monetary policy inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures and reversals during risk aversion.

Chart IIA2-19, US, Exports Price Index of Agricultural Commodities, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1986-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-20 shows the export price index of nonagricultural commodities from 2001 to 2013. Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates drove price behavior during the past decade. Policy has been based on the myth of stimulating the economy by climbing the negative slope of an imaginary short-term Phillips curve.

Chart IIA2-20, US, Exports Price Index of Nonagricultural Commodities, 2001=100, 2001-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Chart IIA2-21 provides a longer perspective of the price index of US nonagricultural commodities from 1982 to 2013. Increases and decreases around the global contraction after 2007 were caused by carry trade induced by unconventional monetary policy.

Chart IIA2-21, US, Exports Price Index of Nonagricultural Commodities, 2001=100, 1982-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

Finally, Chart IIA2-22 provides 12-month percentage changes of the price index of US exports of nonagricultural commodities from 1986 to 2013. The wide swings before, during and after the global recession beginning in 2007 were caused by carry trades induced by unconventional monetary policy.

Chart IIA2-22, US, Exports Price Index of Nonagricultural Commodities, 12-Month Percentage Changes, 1986-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm

IE Theory and Reality of Economic History and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation. Fear of deflation as had occurred during the Great Depression and in Japan was used as an argument for the first round of unconventional monetary policy with 1 percent interest rates from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004 and quantitative easing in the form of withdrawal of supply of 30-year securities by suspension of the auction of 30-year Treasury bonds with the intention of reducing mortgage rates (for fear of deflation see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, and Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-95). The financial crisis and global recession were caused by interest rate and housing subsidies and affordability policies that encouraged high leverage and risks, low liquidity and unsound credit (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 157-66, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 217-27, International Financial Architecture (2005), 15-18, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II (2008b), 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 182-4). Several past comments of this blog elaborate on these arguments, among which: http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/professor-mckinnons-bubble-economy.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/world-inflation-quantitative-easing.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/treasury-yields-valuation-of-risk.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/11/quantitative-easing-theory-evidence-and.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html

If the forecast of the central bank is of recession and low inflation with controlled inflationary expectations, monetary policy should consist of lowering the short-term policy rate of the central bank, which in the US is the fed funds rate. The intended effect is to lower the real rate of interest (Svensson 2003LT, 146-7). The real rate of interest, r, is defined as the nominal rate, i, adjusted by expectations of inflation, π*, with all variables defined as proportions: (1+r) = (1+i)/(1+π*) (Fisher 1930). If i, the fed funds rate, is lowered by the Fed, the numerator of the right-hand side is lower such that if inflationary expectations, π*, remain unchanged, the left-hand (1+r) decreases, that is, the real rate of interest, r, declines. Expectations of lowering short-term real rates of interest by policy of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) fixing a lower fed funds rate would lower long-term real rates of interest, inducing with a lag investment and consumption, or aggregate demand, that can lift the economy out of recession. Inflation also increases with a lag by higher aggregate demand and inflation expectations (Fisher 1933). This reasoning explains why the FOMC lowered the fed funds rate in Dec 2008 to 0 to 0.25 percent and left it unchanged.

The fear of the Fed is expected deflation or negative π*. In that case, (1+ π*) < 1, and (1+r) would increase because the right-hand side of the equation would be divided by a fraction. A simple numerical example explains the effect of deflation on the real rate of interest. Suppose that the nominal rate of interest or fed funds rate, i, is 0.25 percent, or in proportion 0.25/100 = 0.0025, such that (1+i) = 1.0025. Assume now that economic agents believe that inflation will remain at 1 percent for a long period, which means that π* = 1 percent, or in proportion 1/100 =0.01. The real rate of interest, using the equation, is (1+0.0025)/(1+0.01) = (1+r) = 0.99257, such that r = 0.99257 - 1 = -0.00743, which is a proportion equivalent to –(0.00743)100 = -0.743 percent. That is, Fed policy has created a negative real rate of interest of 0.743 percent with the objective of inducing aggregate demand by higher investment and consumption. This is true if expected inflation, π*, remains at 1 percent. Suppose now that expectations of deflation become generalized such that π* becomes -1 percent, that is, the public believes prices will fall at the rate of 1 percent in the foreseeable future. Then the real rate of interest becomes (1+0.0025) divided by (1-0.01) equal to (1.0025)/(0.99) = (1+r) = 1.01263, or r = (1.01263-1) = 0.01263, which results in positive real rate of interest of (0.01263)100 = 1.263 percent.

Irving Fisher also identified the impact of deflation on debts as an important cause of deepening contraction of income and employment during the Great Depression illustrated by an actual example (Fisher 1933, 346):

“By March, 1933, liquidation had reduced the debts about 20 percent, but had increased the dollar about 75 percent, so that the real debt, that is the debt measured in terms of commodities, was increased about 40 percent [100%-20%)X(100%+75%) =140%]. Unless some counteracting cause comes along to prevent the fall in the price level, such a depression as that of 1929-1933 (namely when the more the debtors pay the more they owe) tends to continue, going deeper, in a vicious spiral, for many years. There is then no tendency of the boat to stop tipping until it has capsized”

The nominal rate of interest must always be nonnegative, that is, i ≥ 0 (Hick 1937, 154-5):

“If the costs of holding money can be neglected, it will always be profitable to hold money rather than lend it out, if the rate of interest is not greater than zero. Consequently the rate of interest must always be positive. In an extreme case, the shortest short-term rate may perhaps be nearly zero. But if so, the long-term rate must lie above it, for the long rate has to allow for the risk that the short rate may rise during the currency of the loan, and it should be observed that the short rate can only rise, it cannot fall”

The interpretation by Hicks of the General Theory of Keynes is the special case in which at interest rates close to zero liquidity preference is infinitely or perfectly elastic, that is, the public holds infinitely large cash balances at that near zero interest rate because there is no opportunity cost of foregone interest. Increases in the money supply by the central bank would not decrease interest rates below their near zero level, which is called the liquidity trap. The only alternative public policy would consist of fiscal policy that would act similarly to an increase in investment, increasing employment without raising the interest rate.

An influential view on the policy required to steer the economy away from the liquidity trap is provided by Paul Krugman (1998). Suppose the central bank faces an increase in inflation. An important ingredient of the control of inflation is the central bank communicating to the public that it will maintain a sustained effort by all available policy measures and required doses until inflation is subdued and price stability is attained. If the public believes that the central bank will control inflation only until it declines to a more benign level but not sufficiently low level, current expectations will develop that inflation will be higher once the central bank abandons harsh measures. During deflation and recession the central bank has to convince the public that it will maintain zero interest rates and other required measures until the rate of inflation returns convincingly to a level consistent with expansion of the economy and stable prices. Krugman (1998, 161) summarizes the argument as:

“The ineffectuality of monetary policy in a liquidity trap is really the result of a looking-glass version of the standard credibility problem: monetary policy does not work because the public expects that whatever the central bank may do now, given the chance, it will revert to type and stabilize prices near their current level. If the central bank can credibly promise to be irresponsible—that is, convince the market that it will in fact allow prices to rise sufficiently—it can bootstrap the economy out of the trap”

This view is consistent with results of research by Christina Romer that “the rapid rates of growth of real output in the mid- and late 1930s were largely due to conventional aggregate demand stimulus, primarily in the form of monetary expansion. My calculations suggest that in the absence of these stimuli the economy would have remained depressed far longer and far more deeply than it actually did” (Romer 1992, 757-8, cited in Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 210-2). The average growth rate of the money supply in 1933-1937 was 10 percent per year and increased in the early 1940s. Romer calculates that GDP would have been much lower without this monetary expansion. The growth of “the money supply was primarily due to a gold inflow, which was in turn due to the devaluation in 1933 and to capital flight from Europe because of political instability after 1934” (Romer 1992, 759). Gold inflow coincided with the decline in real interest rates in 1933 that remained negative through the latter part of the 1930s, suggesting that they could have caused increases in spending that was sensitive to declines in interest rates. Bernanke finds dollar devaluation against gold to have been important in preventing further deflation in the 1930s (Bernanke 2002):

“There have been times when exchange rate policy has been an effective weapon against deflation. A striking example from US history is Franklin Roosevelt’s 40 percent devaluation of the dollar against gold in 1933-34, enforced by a program of gold purchases and domestic money creation. The devaluation and the rapid increase in money supply it permitted ended the US deflation remarkably quickly. Indeed, consumer price inflation in the United States, year on year, went from -10.3 percent in 1932 to -5.1 percent in 1933 to 3.4 percent in 1934. The economy grew strongly, and by the way, 1934 was one of the best years of the century for the stock market”

Fed policy is seeking what Irving Fisher proposed “that great depressions are curable and preventable through reflation and stabilization” (Fisher 1933, 350).

The President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago argues that (Charles Evans 2010):

“I believe the US economy is best described as being in a bona fide liquidity trap. Highly plausible projections are 1 percent for core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation at the end of 2012 and 8 percent for the unemployment rate. For me, the Fed’s dual mandate misses are too large to shrug off, and there is currently no policy conflict between improving employment and inflation outcomes”

There are two types of monetary policies that could be used in this situation. First, the Fed could announce a price-level target to be attained within a reasonable time frame (Evans 2010):

“For example, if the slope of the price path is 2 percent and inflation has been underunning the path for some time, monetary policy would strive to catch up to the path. Inflation would be higher than 2 percent for a time until the path was reattained”

Optimum monetary policy with interest rates near zero could consist of “bringing the price level back up to a level even higher than would have prevailed had the disturbance never occurred” (Gauti Eggertsson and Michael Woodford 2003, 207). Bernanke (2003JPY) explains as follows:

“Failure by the central bank to meet its target in a given period leads to expectations of (and public demands for) increased effort in subsequent periods—greater quantities of assets purchased on the open market for example. So even if the central bank is reluctant to provide a time frame for meetings its objective, the structure of the price-level objective provides a means for the bank to commit to increasing its anti-deflationary efforts when its earlier efforts prove unsuccessful. As Eggertsson and Woodford show, the expectations that an increasing price level gap will give rise to intensified effort by the central bank should lead the public to believe that ultimately inflation will replace deflation, a belief that supports the central bank’s own objectives by lowering the current real rate of interest”

Second, the Fed could use its balance sheet to increase purchases of long-term securities together with credible commitment to maintain the policy until the dual mandates of maximum employment and price stability are attained.

In the restatement of the liquidity trap and large-scale policies of monetary/fiscal stimulus, Krugman (1998, 162) finds:

“In the traditional open economy IS-LM model developed by Robert Mundell [1963] and Marcus Fleming [1962], and also in large-scale econometric models, monetary expansion unambiguously leads to currency depreciation. But there are two offsetting effects on the current account balance. On one side, the currency depreciation tends to increase net exports; on the other side, the expansion of the domestic economy tends to increase imports. For what it is worth, policy experiments on such models seem to suggest that these effects very nearly cancel each other out.

Krugman (1998) uses a different dynamic model with expectations that leads to similar conclusions.

The central bank could also be pursuing competitive devaluation of the national currency in the belief that it could increase inflation to a higher level and promote domestic growth and employment at the expense of growth and unemployment in the rest of the world. An essay by Chairman Bernanke in 1999 on Japanese monetary policy received attention in the press, stating that (Bernanke 2000, 165):

“Roosevelt’s specific policy actions were, I think, less important than his willingness to be aggressive and experiment—in short, to do whatever it took to get the country moving again. Many of his policies did not work as intended, but in the end FDR deserves great credit for having the courage to abandon failed paradigms and to do what needed to be done”

Quantitative easing has never been proposed by Chairman Bernanke or other economists as certain science without adverse effects. What has not been mentioned in the press is another suggestion to the Bank of Japan (BOJ) by Chairman Bernanke in the same essay that is very relevant to current events and the contentious issue of ongoing devaluation wars (Bernanke 2000, 161):

“Because the BOJ has a legal mandate to pursue price stability, it certainly could make a good argument that, with interest rates at zero, depreciation of the yen is the best available tool for achieving its mandated objective. The economic validity of the beggar-thy-neighbor thesis is doubtful, as depreciation creates trade—by raising home country income—as well as diverting it. Perhaps not all those who cite the beggar-thy-neighbor thesis are aware that it had its origins in the Great Depression, when it was used as an argument against the very devaluations that ultimately proved crucial to world economic recovery. A yen trading at 100 to the dollar is in no one’s interest”

Chairman Bernanke is referring to the argument by Joan Robinson based on the experience of the Great Depression that: “in times of general unemployment a game of beggar-my-neighbour is played between the nations, each one endeavouring to throw a larger share of the burden upon the others” (Robinson 1947, 156). Devaluation is one of the tools used in these policies (Robinson 1947, 157). Banking crises dominated the experience of the United States, but countries that recovered were those devaluing early such that competitive devaluations rescued many countries from a recession as strong as that in the US (see references to Ehsan Choudhri, Levis Kochin and Barry Eichengreen in Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 205-9; for the case of Brazil that devalued early in the Great Depression recovering with an increasing trade balance see Pelaez, 1968, 1968b, 1972; Brazil devalued and abandoned the gold standard during crises in the historical period as shown by Pelaez 1976, Pelaez and Suzigan 1981). Beggar-my-neighbor policies did work for individual countries but the criticism of Joan Robinson was that it was not optimal for the world as a whole.

Chairman Bernanke (2013Mar 25) reinterprets devaluation and recovery from the Great Depression:

“The uncoordinated abandonment of the gold standard in the early 1930s gave rise to the idea of "beggar-thy-neighbor" policies. According to this analysis, as put forth by important contemporary economists like Joan Robinson, exchange rate depreciations helped the economy whose currency had weakened by making the country more competitive internationally. Indeed, the decline in the value of the pound after 1931 was associated with a relatively early recovery from the Depression by the United Kingdom, in part because of some rebound in exports. However, according to this view, the gains to the depreciating country were equaled or exceeded by the losses to its trading partners, which became less internationally competitive--hence, ‘beggar thy neighbor.’ Economists still agree that Smoot-Hawley and the ensuing tariff wars were highly counterproductive and contributed to the depth and length of the global Depression. However, modern research on the Depression, beginning with the seminal 1985 paper by Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs, has changed our view of the effects of the abandonment of the gold standard. Although it is true that leaving the gold standard and the resulting currency depreciation conferred a temporary competitive advantage in some cases, modern research shows that the primary benefit of leaving gold was that it freed countries to use appropriately expansionary monetary policies. By 1935 or 1936, when essentially all major countries had left the gold standard and exchange rates were market-determined, the net trade effects of the changes in currency values were certainly small. Yet the global economy as a whole was much stronger than it had been in 1931. The reason was that, in shedding the strait jacket of the gold standard, each country became free to use monetary policy in a way that was more commensurate with achieving full employment at home.”

Nurkse (1944) raised concern on the contraction of trade by competitive devaluations during the 1930s. Haberler (1937) dwelled on the issue of flexible exchange rates. Bordo and James (2001) provide perceptive exegesis of the views of Haberler (1937) and Nurkse (1944) together with the evolution of thought by Haberler. Policy coordination among sovereigns may be quite difficult in practice even if there were sufficient knowledge and sound forecasts. Friedman (1953) provided strong case in favor of a system of flexible exchange rates.

Eichengreen and Sachs (1985) argue theoretically with measurements using a two-sector model that it is possible for series of devaluations to improve the welfare of all countries. There were adverse effects of depreciation on other countries but depreciation by many countries could be beneficial for all. The important counterfactual is if depreciations by many countries would have promoted faster recovery from the Great Depression. Depreciation in the model of Eichengreen and Sachs (1985) affected domestic and foreign economies through real wages, profitability, international competitiveness and world interest rates. Depreciation causes increase in the money supply that lowers world interest rates, promoting growth of world output. Lower world interest rates could compensate contraction of output from the shift of demand away from home goods originating in neighbor’s exchange depreciation. Eichengreen and Sachs (1985, 946) conclude:

“This much, however, is clear. We do not present a blanket endorsement of the competitive devaluations of the 1930s. Though it is indisputable that currency depreciation conferred macroeconomic benefits on the initiating country, because of accompanying policies the depreciations of the 1930s had beggar-thy-neighbor effects. Though it is likely that currency depreciation (had it been even more widely adopted) would have worked to the benefit of the world as a whole, the sporadic and uncoordinated approach taken to exchange-rate policy in the 1930s tended, other things being equal, to reduce the magnitude of the benefits.”

There could major difference in the current world economy. The initiating impulse for depreciation originates in zero interest rates on the fed funds rate. The dollar is the world’s reserve currency. Risk aversion intermittently channels capital flight to the safe haven of the dollar and US Treasury securities. In the absence of risk aversion, zero interest rates induce carry trades of short positions in dollars and US debt (borrowing) together with long leveraged exposures in risk financial assets such as stocks, emerging stocks, commodities and high-yield bonds. Without risk aversion, the dollar depreciates against every currency in the world. The dollar depreciated against the euro by 39.3 percent from USD 1.1423/EUR con Jun 26, 2003 to USD 1.5914/EUR on Jun 14, 2008 during unconventional monetary policy before the global recession (Table VI-1). Unconventional monetary policy causes devaluation of the dollar relative to other currencies, which can increases net exports of the US that increase aggregate economic activity (Yellen 2011AS). The country issuing the world’s reserve currency appropriates the advantage from initiating devaluation that in policy intends to generate net exports that increase domestic output.

Pelaez and Pelaez (Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 208-209) summarize the experience of Brazil as follows:

“During 1927–9, Brazil accumulated £30 million of foreign exchange of which £20 million were deposited at its stabilization fund (Pelaez 1968, 43–4). After the decline in coffee prices and the first impact of the Great Depression in Brazil a hot money movement wiped out foreign exchange reserves. In addition, capital inflows stopped entirely. The deterioration of the terms of trade further complicated matters, as the value of exports in foreign currency declined abruptly. Because of this exchange crisis, the service of the foreign debt of Brazil became impossible. In August 1931, the federal government was forced to cancel the payment of principal on certain foreign loans. The balance of trade in 1931 was expected to yield £20 million whereas the service of the foreign debt alone amounted to £22.6 million. Part of the solution given to these problems was typical of the 1930s. In September 1931, the government of Brazil required that all foreign transactions were to be conducted through the Bank of Brazil. This monopoly of foreign exchange was exercised by the Bank of Brazil for the following three years. Export permits were granted only after the exchange derived from sales abroad was officially sold to the Bank, which in turn allocated it in accordance with the needs of the economy. An active black market in foreign exchange developed. Brazil was in the first group of countries that abandoned early the gold standard, in 1931, and suffered comparatively less from the Great Depression. The Brazilian federal government, advised by the BOE, increased taxes and reduced expenditures in 1931 to compensate a decline in custom receipts (Pelaez 1968, 40). Expenditures caused by a revolution in 1932 in the state of Sao Paulo and a drought in the northeast explain the deficit. During 1932–6, the federal government engaged in strong efforts to stabilize the budget. Apart from the deliberate efforts to balance the budget during the 1930s, the recovery in economic activity itself may have induced a large part of the reduction of the deficit (Ibid, 41). Brazil’s experience is similar to that of the United States in that fiscal policy did not promote recovery from the Great Depression.”

Is depreciation of the dollar the best available tool currently for achieving the dual mandate of higher inflation and lower unemployment? Bernanke (2002) finds dollar devaluation against gold to have been important in preventing further deflation in the 1930s (http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021121/default.htm):

“Although a policy of intervening to affect the exchange value of the dollar is nowhere on the horizon today, it's worth noting that there have been times when exchange rate policy has been an effective weapon against deflation. A striking example from U.S. history is Franklin Roosevelt's 40 percent devaluation of the dollar against gold in 1933-34, enforced by a program of gold purchases and domestic money creation. The devaluation and the rapid increase in money supply it permitted ended the U.S. deflation remarkably quickly. Indeed, consumer price inflation in the United States, year on year, went from -10.3 percent in 1932 to -5.1 percent in 1933 to 3.4 percent in 1934.17 The economy grew strongly, and by the way, 1934 was one of the best years of the century for the stock market. If nothing else, the episode illustrates that monetary actions can have powerful effects on the economy, even when the nominal interest rate is at or near zero, as was the case at the time of Roosevelt's devaluation.”

Should the US devalue following Roosevelt? Alternatively, has monetary policy intended devaluation? Fed policy is seeking, deliberately or as a side effect, what Irving Fisher proposed “that great depressions are curable and preventable through reflation and stabilization” (Fisher, 1933, 350). The Fed has created not only high volatility of assets but also what many countries are regarding as a competitive devaluation similar to those criticized by Nurkse (1944). Yellen (2011AS, 6) admits that Fed monetary policy results in dollar devaluation with the objective of increasing net exports, which was the policy that Joan Robinson (1947) labeled as “beggar-my-neighbor” remedies for unemployment.