Financial Volatility, Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars below Trend, Destruction of Household Nonfinancial Wealth with Stagnating Total Real Wealth, United States Commercial Banks, United States Housing Collapse, Household Income at 1995 Levels, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

I Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars Below Trend

IA Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IA2 Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits

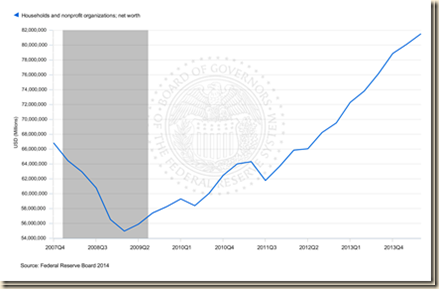

IB Destruction of Household Nonfinancial Wealth with Stagnating Total Real Wealth

IIA United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

IA Transmission of Monetary Policy

IB Functions of Banking

Appendix on Monetary Policy

IA1 Theory

IA2 Policy

IA3 Evidence

IA4 Unwinding Strategy

IC United States Commercial Banks Assets and Liabilities

ID Theory and Reality of Economic History, Cyclical Slow Growth not Secular Stagnation and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

IIB United States Housing Collapse

IIC Household Income at 1995 Levels, 45 Million in Poverty and 41 Million without Health Insurance

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

IA Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars below Trend. The US is experiencing the first expansion from a recession after World War II with stressing socioeconomic conditions:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources with GDP two trillion dollars below trend (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html). US GDP grew at the average rate of 3.3 percent per year from 1929 to 2013 with similar performance in whole cycles of contractions and expansions but only at 0.9 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2013. GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.6 percent than what it would have been had it grown at trend of 3.0 percent.

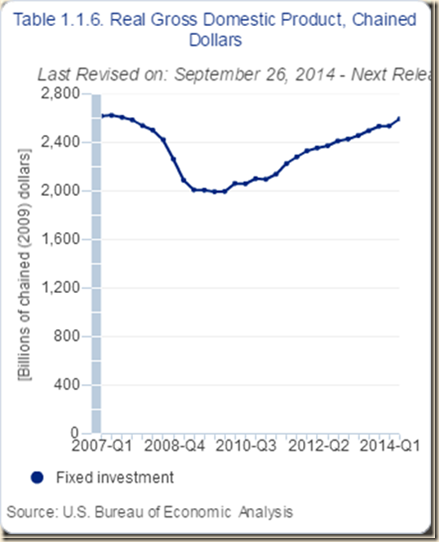

- Private fixed investment stagnating at change of 0.3 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html)

- Twenty seven million or 16.4 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitics-monetary-policy-and.html)

- Productivity growth fell from 2.2 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2013 to 1.5 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2013 deteriorating future growth and prosperity (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html)

- Output of manufacturing in Aug at 17.6 percent below long-term trend since 1919 and at 13.8 percent below trend since 1986 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins of production across countries in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html)

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/fluctuating-financial-valuations.html)

- 45 million in poverty and 41 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1995 levels (Section II and earlier(http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by 7.5 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 when it would have been over 22.0 percent at trend of 3.1 percent per year in real terms from 1945 to 2013 (Section IB and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/financial-indecision-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/global-financial-risks-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html). Financial assets increased $14.2 trillion while nonfinancial assets increased $224.1 billion with likely concentration of wealth in those with access to sophisticated financial investments. Real estate assets adjusted for inflation fell 13.5 percent from 2007 to IIQ2014.

Valuations of risk financial assets approach historical highs. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.2 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 20 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the third estimate of GDP for IIQ2014 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp2q14_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,745.9 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,355.6 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,745.9/$14,355.6 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 would have accumulated to 22.1 percent. GDP in IIQ2014 would be $18,305.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,294.6 billion than actual $16,010.4 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.9 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.4 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/fluctuating-financial-valuations.html). US GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,010.4 billion in IIQ2014 or 6.8 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Jul 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.2212 in Aug 2014. The actual index NSA in Aug 2014 is 101.5145, which is 17.6 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 117.7603 in Aug 2014. The output of manufacturing at 101.5145 in Aug 2014 is 13.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation. The economy of the US can be summarized in growth of economic activity or GDP as fluctuating from mediocre growth of 2.5 percent on an annual basis in 2010 to 1.6 percent in 2011, 2.3 percent in 2012 and 2.2 percent in 2013. The following calculations show that actual growth is around 2.1 to 2.6 percent per year. The rate of growth of 0.9 percent in the entire cycle from 2007 to 2013 is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which the economy of the US always attained for entire cycles in expansions after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May). Revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) provide important information on long-term growth and cyclical behavior. Table Summary provides relevant data.

Table Summary, Long-term and Cyclical Growth of GDP, Real Disposable Income and Real Disposable Income per Capita

| GDP | ||

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2013 | 3.3 | |

| 1947-2013 | 3.2 | |

| Whole Cycles | ||

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 | |

| 2006-2013 | 1.0 | |

| 2007-2013 | 0.9 | |

| Cyclical Contractions ∆% | ||

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980, IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | -4.7 | |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | -4.2 | |

| Cyclical Expansions Average Annual Equivalent ∆% | ||

| IQ1983 to IVQ1985 IQ1983-IQ1986 IQ1983-IIIQ1986 IQ1983-IVQ1986 IQ1983-IQ1987 IQ1983-IIQ1987 IQ1983-IIIQ1987 IQ1983 to IVQ1987 | 5.9 5.7 5.4 5.2 5.0 5.0 4.9 5.0 | |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 7.8 | |

| IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014 | 2.2 | |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 | |

| Real Disposable Income | Real Disposable Income per Capita | |

| Long-Term | ||

| 1929-2013 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| 1947-1999 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| Whole Cycles | ||

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 | 2.6 |

| 2006-2013 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) also provide critical information in assessing the current rhythm of US economic growth. The economy appears to be moving at a pace from 2.1 to 2.5 percent per year. Table Summary GDP provides the data.

1. Average Annual Growth in the Past Eight Quarters. GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012, the four quarters of 2013 and the first two quarters of 2014 accumulated to 5.4 percent. This growth is equivalent to 2.1 percent per year, obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2014 of $16,010.4 billion by GDP in IVQ2011 of $15,190.3 billion and compounding by 4/10: {[($16,010.4/$15,190.3)4/10 -1]100 = 2.1 percent.

2. Average Annual Growth in the Past Four Quarters. GDP growth in the four quarters of IIQ2013 to IIQ2014 accumulated to 2.6 percent that is equivalent to 2.6 percent in a year. This is obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2014 of $16,010.4 billion by GDP in IIQ2013 of $15,606.6 billion and compounding by 4/4: {[($16,010.4/$15,606.6)4/4 -1]100 = 2.6%}. The US economy grew 2.6 percent in IIQ2014 relative to the same quarter a year earlier in IIQ2013. Another important revelation of the revisions and enhancements is that GDP was flat in IVQ2012, which is in the borderline of contraction, and negative in IQ2014. US GDP fell 0.5 percent in IQ2014. The rate of growth of GDP in the revision of IIIQ2013 is 4.5 percent in seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR). Inventory accumulation contributed 1.49 percentage points to this rate of growth. The actual rate without this impulse of unsold inventories would have been 3.0 percent, or 0.74 percent in IIIQ2013, such that annual equivalent growth in 2013 is closer to 2.8 percent {[(1.007)(1.004)(1.0074)(1.009)4/4-1]100 = 2.8%}, compounding the quarterly rates and converting into annual equivalent. Inventory divestment deducted 1.16 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2014. Without this deduction of inventory divestment, GDP growth would have been minus 0.9 percent in IQ2014, such that the actual growth rates in the four quarters ending in IQ2014 is closer to 2.2 percent {[(1.004)(1.011)(1.009)(0.9977)]4/4 -1]100 = 2.2%}.

Table Summary GDP, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2009 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 14,991.8 | NA | NA | 1.9 |

| IVQ2011 | 15,190.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| IQ2012 | 15,275.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.6 |

| IIQ2012 | 15,336.7 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| IIIQ2012 | 15,431.3 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 2.7 |

| IVQ2012 | 15,433.7 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| IQ2013 | 15,538.4 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| IIQ2013 | 15,606.6 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| IIIQ2013 | 15,779.9 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| IVQ2013 | 15,916.2 | 6.2 | 0.9 | 3.1 |

| IQ2014 | 15,831.7 | 5.6 | -0.5 | 1.9 |

| IIQ2014 | 16,010.4 | 6.8 | 1.1 | 2.6 |

| Cumulative ∆% IQ2012 to IQ2014 | 5.4 | 5.4 | ||

| Annual Equivalent ∆% | 2.1 | 2.1 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Historical parallels are instructive but have all the limitations of empirical research in economics. The more instructive comparisons are not with the Great Depression of the 1930s but rather with the recessions in the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s. The growth rates and job creation in the expansion of the economy away from recession are subpar in the current expansion compared to others in the past. Four recessions are initially considered, following the reference dates of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html ): IIQ1953-IIQ1954, IIIQ1957-IIQ1958, IIIQ1973-IQ1975 and IQ1980-IIIQ1980. The data for the earlier contractions illustrate that the growth rate and job creation in the current expansion are inferior. The sharp contractions of the 1950s and 1970s are considered in Table I-1, showing the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) quarter-to-quarter, seasonally adjusted (SA), yearly-equivalent growth rates of GDP. The recovery from the recession of 1953 consisted of four consecutive quarters of high percentage growth rates from IIIQ1954 to IIIQ1955: 4.6, 8.0, 11.9 and 6.7. The recession of 1957 was followed by four consecutive high percentage growth rates from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959: 9.6, 9.7, 7.7 and 10.1. The recession of 1973-1975 was followed by high percentage growth rates from IIQ1975 to IQ1976: 3.1, 6.8, 5.5 and 9.3. The disaster of the Great Inflation and Unemployment of the 1970s, which made stagflation notorious, is even better in growth rates during the expansion phase in comparison with the current slow-growth recession.

Table I-1, US, Seasonally Adjusted Quarterly Percentage Growth Rates in Annual Equivalent of GDP in Cyclical Recessions and Following Four Quarter Expansions ∆%

| IQ | IIQ | IIIQ | IV | |

| R IIQ1953-IIQ1954 | ||||

| 1953 | -2.2 | -5.9 | ||

| 1954 | -1.8 | |||

| E IIIQ1954-IIQ1955 | ||||

| 1954 | 4.6 | 8.0 | ||

| 1955 | 11.9 | 6.7 | ||

| R IIIQ1957-IIQ1958 | ||||

| 1957 | -4.0 | |||

| 1958 | -10.0 | |||

| E IIIQ1958-IIQ1959 | ||||

| 1958 | 9.6 | 9.7 | ||

| 1959 | 7.7 | 10.1 | ||

| R IVQ1969-IV1970 | ||||

| 1969 | -1.7 | |||

| 1970 | -0.7 | |||

| E IIQ1970-IQ1971 | ||||

| 1970 | 0.7 | 3.6 | -4.0 | |

| 1971 | 11.1 | |||

| R IVQ1973-IQ1975 | ||||

| 1973 | 3.8 | |||

| 1974 | -3.3 | 1.1 | -3.8 | -1.6 |

| 1975 | -4.7 | |||

| E IIQ1975-IQ1976 | ||||

| 1975 | 3.1 | 6.8 | 5.5 | |

| 1976 | 9.3 | |||

| R IQ1980-IIIQ1980 | ||||

| 1980 | 1.3 | -7.9 | -0.6 | |

| R IQ1981-IVQ1982 | ||||

| 1981 | 8.5 | -2.9 | 4.7 | -4.6 |

| 1982 | -6.5 | 2.2 | -1.4 | 0.4 |

| E IQ1983-IVQ1983 | ||||

| 1983 | 5.3 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 8.5 |

| R IVQ2007-IIQ2009 | ||||

| 2008 | -2.7 | 2.0 | -1.9 | -8.2 |

| 2009 | -5.4 | -0.5 | ||

| E IIIQ2009-IIQ2010 | ||||

| 2009 | 1.3 | 3.9 | ||

| 2010 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The NBER dates another recession in 1980 that lasted about half a year. If the two recessions from IQ1980s to IIIQ1980 and IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 are combined, the impact of lost GDP of 4.7 percent is more comparable to the latest revised 4.2 percent drop of the recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. The recession in 1981-1982 is quite similar on its own to the 2007-2009 recession. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.4 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Table I-2 provides the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) quarterly growth rates of GDP in SA yearly equivalents for the recessions of 1981 to 1982 and 2007 to 2009, using the latest major revision published on July 31, 2013 and the second estimate for IIQ2014 GDP (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp2q14_2nd.pdf), which are available in the dataset of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). There were four quarters of contraction in 1981-1982 ranging in rate from -1.4 percent to -6.5 percent and five quarters of contraction in 2007-2009 ranging in rate from -0.5 percent to -8.2 percent. The striking difference is that in the first twenty quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, shown in Table I-2 in relief, GDP grew at the high quarterly percentage growth rates of 5.3, 9.4, 8.1, 8.5, 8.2, 7.2, 4.0, 3.2, 4.0, 3.7, 6.4, 3.0, 3.8, 1.9, 4.1, 2.1, 2.8, 4.6, 3.7 and 6.8. In contrast, the percentage growth rates in the first twenty quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014 shown in relief in Table I-2 were mediocre: 1.3, 3.9, 1.7, 3.9, 2.7, 2.5, -1.5, 2.9, 0.8, 4.6, 2.3, 1.6, 2.5, 0.1, 2.7, 1.8, 4.5, 3.5, minus 2.1 and 4.6. Inventory accumulation contributed 2.80 percentage points to the rate of growth of 4.6 percent in IVQ2011. Inventory divestment deducted 1.16 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2014 and added 1.42 percentage points to the rate of growth in IIQ2014. Economic growth and employment creation continued at slow rhythm during 2012 and in 2013 while much stronger growth would be required in movement to full employment. The cycle is now long by historical standards and growth rates are typically weaker in the final periods of cyclical expansions.

Table I-2, US, Quarterly Growth Rates of GDP, % Annual Equivalent SA

| Q | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

| I | 8.5 | -6.5 | 5.3 | 8.2 | -2.7 | -5.4 | 1.7 |

| II | -2.9 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 7.2 | 2.0 | -0.5 | 3.9 |

| III | 4.7 | -1.4 | 8.1 | 4.0 | -1.9 | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| IV | -4.6 | 0.4 | 8.5 | 3.2 | -8.2 | 3.9 | 2.5 |

| 1985 | 2011 | ||||||

| I | 4.0 | -1.5 | |||||

| II | 3.7 | 2.9 | |||||

| III | 6.4 | 0.8 | |||||

| IV | 3.0 | 4.6 | |||||

| 1986 | 2012 | ||||||

| I | 3.8 | 2.3 | |||||

| II | 1.9 | 1.6 | |||||

| III | 4.1 | 2.5 | |||||

| IV | 2.1 | 0.1 | |||||

| 1987 | 2013 | ||||||

| I | 2.8 | 2.7 | |||||

| II | 4.6 | 1.8 | |||||

| III | 3.7 | 4.5 | |||||

| IV | 6.8 | 3.5 | |||||

| 1988 | 2014 | ||||||

| I | 2.3 | -2.1 | |||||

| II | 5.4 | 4.6 | |||||

| III | 2.3 | ||||||

| IV | 5.4 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

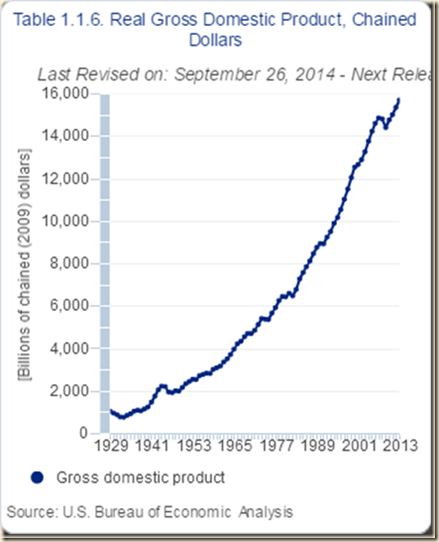

Chart I-1 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides strong growth of real GDP in the US between 1929 and 1999 at the yearly average rate of 3.5 percent. There is an evident acceleration of the rate of GDP growth in the 1990s as shown by a much sharper slope of the growth curve. Cobet and Wilson (2002) define labor productivity as the value of manufacturing output produced per unit of labor input used (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 137-44). Between 1950 and 2000, labor productivity in the US grew less rapidly than in Germany and Japan. The major part of the increase in productivity in Germany and Japan occurred between 1950 and 1973 while the rate of productivity growth in the US was relatively subdued in several periods. While Germany and Japan reached their highest growth rates of productivity before 1973, the US accelerated its rate of productivity growth in the second half of the 1990s. Between 1950 and 2000, the rate of productivity growth in the US of 2.9 percent per year was much lower than 6.3 percent in Japan and 4.7 percent in Germany. Between 1995 and 2000, the rate of productivity growth of the US of 4.6 percent exceeded that of Japan of 3.9 percent and the rate of Germany of 2.6 percent.

Chart I-1, US, Real GDP 1929-1999

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-1A provides real GDP annually from 1929 to 2013. Growth after the global recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 has not been sufficiently high to compensate for the contraction as it had occurred in past economic cycles. GDP is about two trillion dollars lower than trend GDP, explaining 26.9 million unemployed or underemployed. There is dramatic decline of productivity growth in the whole cycle from 2.2 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2013 to 1.5 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html). There is profound drop in the average rate of output growth from 3.2 percent on average from 1947 to 2013 to 1.0 percent from 2007 to 2013. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 would have accumulated to 22.1 percent. GDP in IIQ2014 would be $18,305.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,294.6 billion than actual $16,010.4 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.9 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.4 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/fluctuating-financial-valuations.html). US GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,010.4 billion in IIQ2014 or 6.8 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Jul 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.2212 in Aug 2014. The actual index NSA in Aug 2014 is 101.5145, which is 17.6 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 117.7603 in Aug 2014. The output of manufacturing at 101.5145 in Aug 2014 is 13.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Chart I-1A, US, Real GDP 1929-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

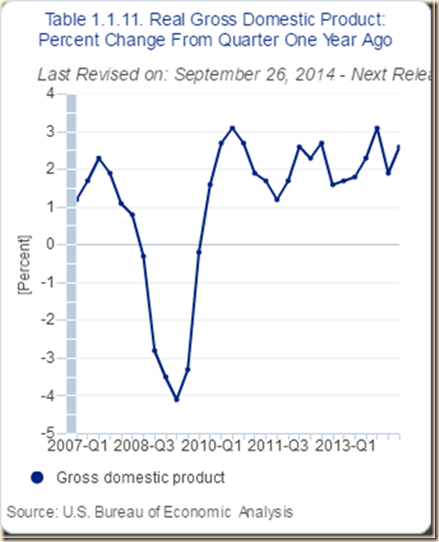

Chart I-2 provides the growth of real quarterly GDP in the US between 1947 and 2014. The drop of output in the recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 has been followed by anemic recovery compared with return to trend at 3.0 percent from 1870 to 2010 after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May) and a standstill that can lead to growth recession, or low rates of economic growth. The expansion is relatively long compared to earlier expansion and there could be even another contraction or conventional recession in the future. The average rate of growth from 1947 to 2013 is 3.2 percent. The average growth rate from IV2007 to IVQ2013 is only 1.0 percent with 2.8 percent annual equivalent from the end of the recession in IVQ2001 to the end of the expansion in IVQ2007.

Chart I-2, US, Real GDP, Quarterly, 1947-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

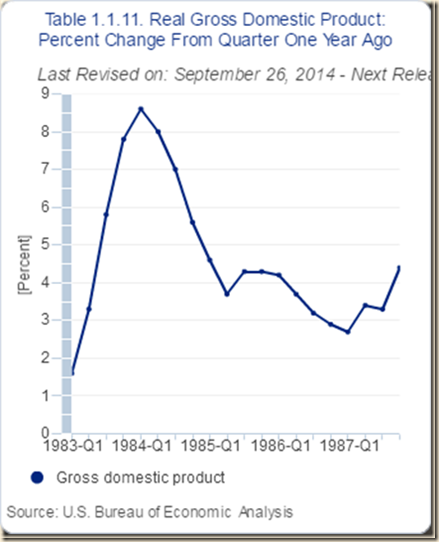

Chart I-3 provides real GDP percentage change on the quarter a year earlier for 1983-1984. The objective is simply to compare expansion in two recoveries from sharp contractions as shown in Table I-2. Growth rates in the early phase of the recovery in 1983 and 1984 were very high, which is the opportunity to reduce unemployment that has characterized cyclical expansion in the postwar US economy.

Chart I-3, Real GDP Percentage Change on Quarter a Year Earlier 1983-1987

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

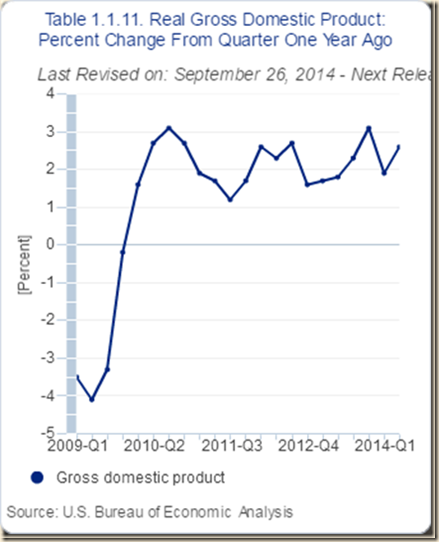

In contrast, growth rates in the comparable first nineteen quarters of expansion from 2009 to 2014 in Chart I-4 have been mediocre. As a result, growth has not provided the exit from unemployment and underemployment as in other cyclical expansions in the postwar period. Growth rates did not rise in V shape as in earlier expansions and then declined close to the standstill of growth recessions.

Chart I-4, US, Real GDP Percentage Change on Quarter a Year Earlier 2009-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table I-3 provides percentage change of real GDP in the United States in the 1930s, 1980s and 2000s. The recession in 1981-1982 is quite similar on its own to the 2007-2009 recession. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.4 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Data are available for the 1930s only on a yearly basis. US GDP fell 4.7 percent in the two recessions (1) from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and (2) from III1981 to IVQ1981 to IVQ1982 and 4.2 percent cumulatively in the recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. It is instructive to compare the first three years of the expansions in the 1980s and the current expansion. GDP grew at 4.6 percent in 1983, 7.3 percent in 1984, 4.2 percent in 1985, 3.5 percent in 1986 and 3.5 percent in 1987. In contrast, GDP grew 2.5 percent in 2010, 1.6 percent in 2011, 2.3 percent in 2012 and 2.2 percent in 2013. Actual annual equivalent GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012, and six quarters from IQ2013 to IIQ2014 is 2.1 percent and 2.6 percent in the four quarters ending in IIQ2014. GDP grew at 4.2 percent in 1985, 3.5 percent in 1986 and 3.5 percent in 1987 while the forecasts of the central tendency of participants of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are in the range of 2.0 to 2.2 percent in 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20140917.pdf) with less reliable forecast of 2.6 to 3.0 percent in 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20140917.pdf ). Growth of GDP in the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014 has been at average 2.2 percent in annual equivalent.

Table I-3, US, Percentage Change of GDP in the 1930s, 1980s and 2000s, ∆%

| Year | GDP ∆% | Year | GDP ∆% | Year | GDP ∆% |

| 1930 | -8.5 | 1980 | -0.2 | 2000 | 4.1 |

| 1931 | -6.4 | 1981 | 2.6 | 2001 | 1.0 |

| 1932 | -12.9 | 1982 | -1.9 | 2002 | 1.8 |

| 1933 | -1.3 | 1983 | 4.6 | 2003 | 2.8 |

| 1934 | 10.8 | 1984 | 7.3 | 2004 | 3.8 |

| 1935 | 8.9 | 1985 | 4.2 | 2005 | 3.3 |

| 1936 | 12.9 | 1986 | 3.5 | 2006 | 2.7 |

| 1937 | 5.1 | 1987 | 3.5 | 2007 | 1.8 |

| 1938 | -3.3 | 1988 | 4.2 | 2008 | -0.3 |

| 1930 | 8.0 | 1989 | 3.7 | 2009 | -2.8 |

| 1940 | 8.8 | 1990 | 1.9 | 2010 | 2.5 |

| 1941 | 17.7 | 1991 | -0.1 | 2011 | 1.6 |

| 1942 | 18.9 | 1992 | 3.6 | 2012 | 2.3 |

| 1943 | 17.0 | 1993 | 2.7 | 2013 | 2.2 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-5 provides percentage change of GDP in the US during the 1930s. There is vast literature analyzing the Great Depression (Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009), 198-217). Cole and Ohanian (1999) find that US real per capita output was lower by 11 percent in 1939 than in 1929 while the typical expansion of real per capita output in the US during a decade is 31 percent. Private hours worked in the US were 25 percent lower in 1939 relative to 1929.

Chart I-5, US, Percentage Change of GDP in the 1930s

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

In contrast, Chart I-6 shows rapid recovery from the recessions in the 1980s. High growth rates in the initial quarters of expansion eliminated the unemployment and underemployment created during the contraction. The economy then returned to grow at the trend of expansion, interrupted by another contraction in 1991.

Chart I-6, US, Percentage Change of GDP in the 1980s

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-7 provides the rates of growth during the 2000s. Growth rates in the initial eighteen quarters of expansion have been relatively lower than during recessions after World War II. As a result, unemployment and underemployment continue at the rate of 16.4 percent of the US labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html) with weak hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitics-monetary-policy-and.html).

Chart I-7, US, Percentage Change of GDP in the 2000s

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Characteristics of the four cyclical contractions are provided in Table I-4 with the first column showing the number of quarters of contraction; the second column the cumulative percentage contraction; and the final column the average quarterly rate of contraction. There were two contractions from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and from IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 separated by three quarters of expansion. The drop of output combining the declines in these two contractions is 4.7 percent, which is almost equal to the decline of 4.2 percent in the contraction from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.4 percent cumulatively and fell 45.3 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7 and revisions in http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is entirely misleading.

Table I-4, US, Number of Quarters, GDP Cumulative Percentage Contraction and Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate in Cyclical Contractions

| Number of Quarters | Cumulative Percentage Contraction | Average Percentage Rate | |

| IIQ1953 to IIQ1954 | 3 | -2.4 | -0.8 |

| IIIQ1957 to IIQ1958 | 3 | -3.0 | -1.0 |

| IVQ1973 to IQ1975 | 5 | -3.1 | -0.6 |

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 | 2 | -2.2 | -1.1 |

| IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | 4 | -2.5 | -0.64 |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | 6 | -4.2 | -0.72 |

Sources: Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table I-5 shows the mediocre average annual equivalent growth rate of 2.2 percent of the US economy in the twenty quarters of the current cyclical expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014. In sharp contrast, the average growth rate of GDP was:

- 5.7 percent in the first thirteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986

- 5.4 percent in the first fifteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986

- 5.2 percent in the first sixteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1986

- 5.0 percent in the first seventeen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1987

- 5.0 percent in the first eighteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIQ1987

- 4.9 percent in the first nineteen quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987

- 5.0 percent in the first twenty quarters of expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1987

The line “average first four quarters in four expansions” provides the average growth rate of 7.7 percent with 7.8 percent from IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955, 9.2 percent from IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959, 6.1 percent from IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 and 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. The United States missed this opportunity of high growth in the initial phase of recovery. BEA data show the US economy in standstill with annual growth of 2.5 percent in 2010 decelerating to 1.6 percent annual growth in 2011, 2.3 percent in 2012 and 2.2 percent in 2013 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) The expansion from IQ1983 to IQ1986 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983. GDP growth in the four quarters of 2012, the four quarters of 2013 and the first two quarters of 2014 accumulated to 5.4 percent. This growth is equivalent to 2.1 percent per year, obtained by dividing GDP in IIQ2014 of $16,010.4 billion by GDP in IVQ2011 of $15,190.3 billion and compounding by 4/10: {[($16,010.4/$15,190.3)4/10 -1]100 = 2.1 percent. The rate of growth of GDP in the revision of the third estimate of IIIQ2013 is 4.5 percent in seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR). Inventory accumulation contributed 1.49 percentage points to this rate of growth. The actual rate without this impulse of unsold inventories would have been 3.0 percent, or 0.74 percent in IIIQ2013, such that annual equivalent growth in 2013 is closer to 2.8 percent {[(1.007)(1.004)(1.0074)(1.009)4/4-1]100 = 2.8%}, compounding the quarterly rates and converting into annual equivalent. Inventory divestment deducted 1.16 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2014. Without this deduction of inventory divestment, GDP growth would have been minus 0.9 percent in IQ2014, such that the actual growth rates in the four quarters ending in IQ2014 is closer to 2.2 percent {[(1.004)(1.011)(1.009)(0.9977)]4/4 -1]100 = 2.2%}.

Table I-5, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Growth and Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate in Cyclical Expansions

| Number | Cumulative Growth ∆% | Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate | |

| IIIQ 1954 to IQ1957 | 11 | 12.8 | 4.5 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1954 to IIQ1955 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| IIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 5 | 10.0 | 7.9 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 4 | 9.2 | |

| IIQ1975 to IVQ1976 | 8 | 8.3 | 4.1 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ1975 to IIQ1976 | 4 | 6.1 | |

| IQ1983-IQ1986 IQ1983-IIIQ1986 IQ1983-IVQ1986 IQ1983-IQ1987 IQ1983-IIQ1987 IQ1983 to IIIQ1987 IQ1983 to IVQ1987 | 13 15 16 17 18 19 20 | 19.9 21.6 22.3 23.1 24.5 25.6 27.7 | 5.7 5.4 5.2 5.0 5.0 4.9 5.0 |

| First Four Quarters IQ1983 to IVQ1983 | 4 | 7.8 | |

| Average First Four Quarters in Four Expansions* | 7.7 | ||

| IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014 | 20 | 11.5 | 2.2 |

| First Four Quarters IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 | 2.7 |

*First Four Quarters: 7.8% IIIQ1954-IIQ1955; 9.2% IIIQ1958-IIQ1959; 6.1% IIIQ1975-IQ1976; 7.8% IQ1983-IVQ1983

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-8 shows US real quarterly GDP growth from 1980 to 1989. The economy contracted during the recession and then expanded vigorously throughout the 1980s, rapidly eliminating the unemployment caused by the contraction.

Chart I-8, US, Real GDP, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-9 shows the entirely different situation of real quarterly GDP in the US between 2007 and 2013. The economy has underperformed during the first twenty quarters of expansion for the first time in the comparable contractions since the 1950s. The US economy is now in a perilous standstill.

Chart I-9, US, Real GDP, 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

As shown in Tables I-4 and I-5 above the loss of real GDP in the US during the contraction was 4.3 percent but the gain in the cyclical expansion has been only 11.4 percent (first to the last row in Table I-5), using all latest revisions. As a result, the level of real GDP in IIQ2014 with the first estimate and revisions is only higher by 6.8 percent than the level of real GDP in IVQ2007. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 would have accumulated to 22.1 percent. GDP in IIQ2014 would be $18,305.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,294.6 billion than actual $16,010.4 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.9 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.4 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/fluctuating-financial-valuations.html). US GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,010.4 billion in IIQ2014 or 6.8 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Jul 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.2212 in Aug 2014. The actual index NSA in Aug 2014 is 101.5145, which is 17.6 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 117.7603 in Aug 2014. The output of manufacturing at 101.5145 in Aug 2014 is 13.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

The contraction actually concentrated in two quarters: decline of 2.1 percent in IVQ2008 relative to the prior quarter and decline of 1.4 percent in IQ2009 relative to IVQ2008. The combined fall of GDP in IVQ2008 and IQ2009 was 3.5 percent {[(1-0.021) x (1-0.014) -1]100 = -3.5%}, or {[(IQ2009 $14,375.0)/(IIIQ2008 $14,891.6) – 1]100 = -3.5%} except for rounding. Those two quarters coincided with the worst effects of the financial crisis (Cochrane and Zingales 2009). GDP fell 0.1 percent in IIQ2009 but grew 0.3 percent in IIIQ2009, which is the beginning of recovery in the cyclical dates of the NBER. Most of the recovery occurred in five successive quarters from IVQ2009 to IVQ2010 of growth of 1.0 percent in IVQ2009, 0.4 percent in IQ2010, 1.0 percent in IIQ2010 and nearly equal growth at 0.7 percent in IIIQ2010 and 0.6 percent in IVQ2010 for cumulative growth in those five quarters of 3.8 percent, obtained by accumulating the quarterly rates {[(1.01 x 1.004 x 1.01 x 1.007 x 1.006) – 1]100 = 3.8%} or {[(IVQ2010 $14,939.0)/(IIIQ2009 $14,402.5) – 1]100 = 3.7%} with minor rounding difference. The economy then stalled during the first half of 2011 with decline of 0.4 percent in IQ2011 and growth of 0.7 percent in IIQ2011 for combined annual equivalent rate of 0.6 percent {(0.996 x 1.007)2}. The economy grew 0.2 percent in IIIQ2011 for annual equivalent growth of 0.7 percent in the first three quarters {[(0.996 x 1.007 x 1.002)4/3 -1]100 = 0.7%}. Growth picked up in IVQ2011 with 1.1 percent relative to IIIQ2011. Growth in a quarter relative to a year earlier in Table I-6 slows from over 2.7 percent during three consecutive quarters from IIQ2010 to IVQ2010 to 1.9 percent in IQ2011, 1.7 percent in IIQ2011, 1.2 percent in IIIQ2011 and 1.7 percent in IVQ2011. As shown below, growth of 1.1 percent in IVQ2011 was partly driven by inventory accumulation. In IQ2012, GDP grew 0.6 percent relative to IVQ2011 and 2.6 percent relative to IQ2011, decelerating to 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 and 2.3 percent relative to IIQ2011 and 0.6 percent in IIIQ2012 and 2.7 percent relative to IIIQ2011 largely because of inventory accumulation and national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.0 percent in IVQ2012 with 1.6 percent relative to a year earlier but mostly because of deduction of 1.80 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.12 percentage points of reduction of one-time national defense expenditures. Growth was 0.7 percent in IQ2013 and 1.7 percent relative to IQ2012 in large part because of burning savings to consume caused by financial repression of zero interest rates. There is similar growth of 0.4 percent in IIQ2013 and 1.8 percent relative to a year earlier. In IIIQ2013, GDP grew 1.1 percent relative to the prior quarter and 2.3 percent relative to the same quarter a year earlier with inventory accumulation contributing 1.49 percentage points to growth at 4.5 percent SAAR in IIIQ2013. GDP increased 0.9 percent in IVQ2013 and 3.1 percent relative to a year earlier. GDP fell 0.5 percent in IQ2014 and grew 1.9 percent relative to a year earlier. Inventory divestment deducted 1.16 percentage points from GDP growth in IQ2014. GDP grew 1.1 percent in IIQ2014, 2.6 percent relative to a year earlier and at 4.6 SAAR with inventory change contributing 1.42 percentage points. Rates of a quarter relative to the prior quarter capture better deceleration of the economy than rates on a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The critical question for which there is not yet definitive solution is whether what lies ahead is continuing growth recession with the economy crawling and unemployment/underemployment at extremely high levels or another contraction or conventional recession. Forecasts of various sources continued to maintain high growth in 2011 without taking into consideration the continuous slowing of the economy in late 2010 and the first half of 2011. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro area and growth in China are common sources of doubts on the rate and direction of economic growth in the US. There is weak internal demand in the US with almost no investment and spikes of consumption driven by burning saving because of financial repression forever in the form of zero interest rates.

Table I-6, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2009 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2009 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 14,991.8 | NA | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| IQ2008 | 14,889.5 | -0.7 | -0.7 | 1.1 |

| IIQ2008 | 14,963.4 | -0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| IIIQ2008 | 14,891.6 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -0.3 |

| IVQ2008 | 14,577.0 | -2.8 | -2.1 | -2.8 |

| IQ2009 | 14,375.0 | -4.1 | -1.4 | -3.5 |

| IIQ2009 | 14,355.6 | -4.2 | -0.1 | -4.1 |

| IIIQ2009 | 14,402.5 | -3.9 | 0.3 | -3.3 |

| IV2009 | 14,541.9 | -3.0 | 1.0 | -0.2 |

| IQ2010 | 14,604.8 | -2.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| IIQ2010 | 14,745.9 | -1.6 | 1.0 | 2.7 |

| IIIQ2010 | 14,845.5 | -1.0 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| IVQ2010 | 14,939.0 | -0.4 | 0.6 | 2.7 |

| IQ2011 | 14,881.3 | -0.7 | -0.4 | 1.9 |

| IIQ2011 | 14,989.6 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| IIIQ2011 | 15,021.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| IVQ2011 | 15,190.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| IQ2012 | 15,275.0 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.6 |

| IIQ2012 | 15,336.7 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| IIIQ2012 | 15,431.3 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 2.7 |

| IVQ2012 | 15,433.7 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| IQ2013 | 15,538.4 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| IIQ2013 | 15,606.6 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 1.8 |

| IIIQ2013 | 15,779.9 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| IVQ2013 | 15,916.2 | 6.2 | 0.9 | 3.1 |

| IQ2014 | 15,831.7 | 5.6 | -0.5 | 1.9 |

| IIQ2014 | 16,010.4 | 6.8 | 1.1 | 2.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-10 provides the percentage change of real GDP from the same quarter a year earlier from 1980 to 1989. There were two contractions almost in succession in 1980 and from 1981 to 1983. The expansion was marked by initial high rates of growth as in other recession in the postwar US period during which employment lost in the contraction was recovered. Growth rates continued to be high after the initial phase of expansion.

Chart I-10, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The experience of recovery after 2009 is not as complete as during the 1980s. Chart I-11 shows the much lower rates of growth in the early phase of the current expansion and sharp decline from an early peak. The US missed the initial high growth rates in cyclical expansions that eliminate unemployment and underemployment.

Chart I-11, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Quarter a Year Earlier 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-12 provides growth rates from a quarter relative to the prior quarter during the 1980s. There is the same strong initial growth followed by a long period of sustained growth.

Chart I-12, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart I-13 provides growth rates in a quarter relative to the prior quarter from 2007 to 2014. Growth in the current expansion after IIIQ2009 has not been as strong as in other postwar cyclical expansions.

Chart I-13, Percentage Change of Real Gross Domestic Product from Prior Quarter 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The revised estimates and earlier estimates from IQ2008 to IQ2014 in seasonally adjusted annual equivalent rates are shown in Table I-7. The strongest revision is for IVQ2008 for which the contraction of GDP is revised from minus 6.8 percent to minus 8.9 percent and minus 8.2 percent. IQ2009 is also revised from contraction of minus 4.9 percent to minus 6.7 percent but then lowered to contraction of 5.3 percent and 5.4 percent. There is only minor revision in IIIQ2008 of the contraction of minus 4.0 percent to minus 3.7 percent and much lower to minus 1.9 percent. Growth of 5.0 percent in IV2009 is revised to 3.8 percent and then increased to 4.0 percent but lowered to 3.9 percent. Growth in IQ2010 is lowered from 3.9 percent to 2.3 percent and 1.7 percent. Growth in IIQ2010 is upwardly revised to 3.8 percent but then lowered to 2.2 percent. The final revision increased growth in IIQ2010 to 3.9 percent. Revisions lowered growth of 1.9 percent in IQ2011 to minus 1.5 percent. The revisions increased growth of 1.8 percent in IQ2013 to 2.7 percent and increased growth of 2.0 percent in IQ2012 to 2.3 percent. The revisions do not alter the conclusion that the current expansion is much weaker than historical sharp contractions since the 1950s and is now changing into slow growth recession with higher risks of contraction and continuing underperformance.

Table I-7, US, Quarterly Growth Rates of GDP, % Annual Equivalent SA, Revised and Earlier Estimates

| Quarters | Rev Jul 30, 2014 | Rev Jul 31, 2013 | Rev Jul 27, 2012 | Rev Jul 29, 2011 | Earlier Estimate |

| 2008 | |||||

| I | -2.7 | -2.7 | -1.8 | -0.7 | |

| II | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| III | -1.9 | -2.0 | -3.7 | -4.0 | |

| IV | -8.2 | -8.3 | -8.9 | -6.8 | |

| 2009 | |||||

| I | -5.4 | -5.4 | -5.3 | -6.7 | -4.9 |

| II | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.7 | -0.7 |

| III | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| IV | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 5.0 |

| 2010 | |||||

| I | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 3.7 |

| II | 3.9 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 1.7 |

| III | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| IV | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| 2011 | |||||

| I | -1.5 | -1.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| II | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.5 | ||

| III | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | ||

| IV | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.1 | ||

| 2012 | |||||

| I | 2.3 | 3.7 | 2.0 | ||

| II | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.3 | ||

| III | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.1 | ||

| IV | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | ||

| 2013 | |||||

| I | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.8 | ||

| II | 1.8 | 2.5 | |||

| III | 4.5 | 4.1 | |||

| IV | 3.5 | 2.6 | |||

| 2014 | |||||

| I | -2.1 | -2.9 |

Note: Rev: Revision

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

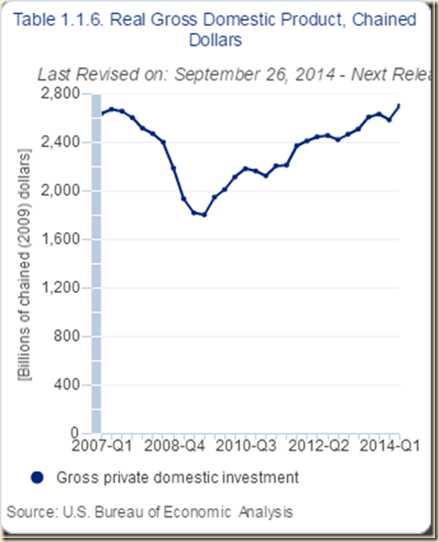

Aggregate demand, personal consumption expenditures (PCE) and gross private domestic investment (GDI) were much stronger during the expansion phase from IQ1983 to IQ1987 than from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2014, as shown in Table I-8. GDI provided the impulse of growth in 1983 and 1984, which has not been the case from 2009 to 2014. The investment decision in the US economy has been frustrated in the current cyclical expansion. Growth of GDP in IIIQ2013 at seasonally adjusted annual rate of 4.5 percent consisted of positive contribution of 1.39 percentage points of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) plus positive contribution of 2.50 percentage points of gross private domestic investment (GDI) of which 1.49 percentage points of inventory investment (∆PI), contribution of net exports (trade or exports less imports) of 0.59 percentage points and 0.04 percentage points of government consumption expenditures and gross investment (GOV) partly because of one-time contribution of national defense expenditures of 0.03 percentage points. Growth at 3.5 percent in IVQ2013 had strongest contributions of 2.51 percentage points of PCE and 1.08 percentage points of trade. Growth of GDP at minus 2.1 percent in IQ2014 is mostly contribution of 0.83 percentage points by PCE with deductions of 1.13 percentage points by GDI, inventory divestment of 1.16 percentage points and trade deducting 1.66 percentage points. Growth at 4.6 percent in IIQ2014 consists of contributions of 1.75 percentage points by PCE and 2.87 percentage points by GDI with 1.42 percentage points by inventory change. Trade deducted 0.34 percentage points and government added 0.31 percentage points mostly because of contribution of 0.38 percentage points of expenditures by state and local government. The economy of the United States has lost the dynamic growth impulse of earlier cyclical expansions with mediocre growth resulting from consumption forced by one-time effects of financial repression, national defense expenditures and inventory accumulation.

Table I-8, US, Contributions to the Rate of Growth of GDP in Percentage Points

| GDP | PCE | GDI | ∆ PI | Trade | GOV | |

| 2014 | ||||||

| I | -2.1 | 0.83 | -1.13 | -1.16 | -1.66 | -0.15 |

| II | 4.6 | 1.75 | 2.87 | 1.42 | -0.34 | 0.31 |

| 2013 | ||||||

| I | 2.7 | 2.45 | 1.12 | 0.70 | -0.08 | -0.75 |

| II | 1.8 | 1.23 | 1.03 | 0.30 | -0.54 | 0.04 |

| III | 4.5 | 1.39 | 2.50 | 1.49 | 0.59 | 0.04 |

| IV | 3.5 | 2.51 | 0.62 | -0.34 | 1.08 | -0.71 |

| 2012 | ||||||

| I | 2.3 | 1.87 | 1.04 | -0.20 | -0.11 | -0.56 |

| II | 1.6 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.27 | -0.04 | -0.08 |

| III | 2.5 | 1.32 | 0.26 | -0.19 | 0.39 | 0.52 |

| IV | 0.1 | 1.32 | -0.84 | -1.80 | 0.79 | -1.20 |

| 2011 | ||||||

| I | -1.5 | 1.38 | -1.07 | -0.96 | -0.24 | -1.60 |

| II | 2.9 | 0.57 | 2.14 | 1.04 | 0.31 | -0.08 |

| III | 0.8 | 1.20 | 0.15 | -2.10 | 0.01 | -0.52 |

| IV | 4.6 | 0.94 | 4.16 | 2.80 | -0.21 | -0.31 |

| 2010 | ||||||

| I | 1.7 | 1.46 | 1.77 | 1.66 | -0.85 | -0.63 |

| II | 3.9 | 2.23 | 2.86 | 1.09 | -1.77 | 0.61 |

| III | 2.7 | 1.77 | 1.86 | 1.90 | -0.83 | -0.07 |

| IV | 2.5 | 2.79 | -0.51 | -1.63 | 1.12 | -0.87 |

| 2009 | ||||||

| I | -5.4 | -0.86 | -7.02 | -2.26 | 2.30 | 0.15 |

| II | -0.5 | -1.19 | -3.25 | -1.12 | 2.34 | 1.56 |

| III | 1.3 | 1.68 | -0.40 | -0.38 | -0.45 | 0.48 |

| IV | 3.9 | -0.01 | 4.05 | 4.40 | 0.06 | -0.17 |

| 1982 | ||||||

| I | -6.5 | 1.61 | -7.59 | -5.33 | -0.49 | -0.05 |

| II | 2.2 | 0.89 | -0.06 | 2.26 | 0.81 | 0.56 |

| III | -1.4 | 1.88 | -0.62 | 1.11 | -3.22 | 0.53 |

| IV | 0.4 | 4.51 | -5.37 | -5.33 | -0.10 | 1.35 |

| 1983 | ||||||

| I | 5.3 | 2.45 | 2.36 | 0.92 | -0.29 | 0.82 |

| II | 9.4 | 5.06 | 5.96 | 3.43 | -2.46 | 0.89 |

| III | 8.1 | 4.50 | 4.40 | 0.57 | -2.25 | 1.42 |

| IV | 8.5 | 4.06 | 6.94 | 3.01 | -1.14 | -1.36 |

| 1984 | ||||||

| I | 8.2 | 2.26 | 7.23 | 4.94 | -2.31 | 1.01 |

| II | 7.2 | 3.64 | 2.57 | -0.29 | -0.87 | 1.87 |

| III | 4.0 | 1.95 | 1.69 | 0.21 | -0.36 | 0.70 |

| IV | 3.2 | 3.29 | -1.08 | -2.44 | -0.56 | 1.58 |

| 1985 | ||||||

| I | 4.0 | 4.23 | -2.14 | -2.86 | 0.94 | 1.01 |

| II | 3.7 | 2.35 | 1.34 | 0.35 | -1.90 | 1.93 |

| III | 6.4 | 4.82 | -0.43 | -0.15 | -0.01 | 1.98 |

| IV | 3.0 | 0.62 | 2.80 | 1.40 | -0.66 | 0.27 |

| 1986 | ||||||

| I | 3.8 | 2.10 | 0.04 | -0.17 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| II | 1.9 | 2.77 | -1.30 | -1.30 | -1.33 | 1.70 |

| III | 4.1 | 4.55 | -1.97 | -1.62 | -0.45 | 1.95 |

| IV | 2.1 | 1.62 | 0.24 | -0.29 | 0.71 | -0.48 |

| 1987 | ||||||

| I | 2.8 | 0.05 | 1.98 | 3.28 | 0.23 | 0.57 |

| II | 4.6 | 3.54 | 0.08 | -0.99 | 0.14 | 0.81 |

| III | 3.7 | 2.97 | 0.03 | -1.19 | 0.45 | 0.23 |

| IV | 6.8 | 0.57 | 4.94 | 4.95 | 0.18 | 1.08 |

Note: PCE: personal consumption expenditures; GDI: gross private domestic investment; ∆ PI: change in private inventories; Trade: net exports of goods and services; GOV: government consumption expenditures and gross investment; – is negative and no sign positive

GDP: percent change at annual rate; percentage points at annual rates

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (pages 1) conducted the annual revision of GDP (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp2q14_adv.pdf):

“The estimates released today reflect the results of the annual revision of the national income and product accounts (NIPAs) in conjunction with the "advance" estimate of GDP for the second quarter of 2014. In addition to the regular revision of estimates for the most recent 3 years and the first quarter of 2014, GDP and select components were revised back to the first quarter of 1999 (see the Technical Note). More information is available in "Preview of Upcoming NIPA Revision" in the May Survey of Current Business and on BEA's Web site. The August Survey will contain an article describing the annual revision in detail. “

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (pages 1-2 http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp2q14_3rd.pdf) explains growth of GDP in IIQ2014 as follows:

“Real gross domestic product -- the output of goods and services produced by labor and property located in the United States -- increased at an annual rate of 4.6 percent in the second quarter of 2014, according to the "third" estimate released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the first quarter, real GDP decreased 2.1 percent.

The GDP estimate released today is based on more complete source data than were available for the "second" estimate issued last month. In the second estimate, the increase in real GDP was 4.2 percent. With the third estimate for the second quarter, the general picture of economic growth remains the same; increases in nonresidential fixed investment and in exports were larger than previously estimated (for more information, see "Revisions" on page 3).

The increase in real GDP in the second quarter primarily reflected positive contributions from personal consumption expenditures (PCE), exports, private inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, state and local government spending, and residential fixed investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.

Real GDP increased 4.6 percent in the second quarter, after decreasing 2.1 percent in the first.

This upturn in the percent change in real GDP primarily reflected upturns in exports and in private inventory investment, accelerations in nonresidential fixed investment and in PCE, and upturns in state and local government spending and in residential fixed investment that were partly offset by an acceleration in imports. “

There are positive contributions to growth in IIQ2014 shown in Table I-9:

- Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) growing at 2.5 percent

- Consumption of durable goods growing at 14.1 percent

- Nonresidential fixed investment growing at 9.7 percent

- Residential fixed investment growing at 8.8 percent

- Government expenditures growing at 1.7 percent

- Exports growing at 11.1 percent

- National defense expenditures growing at 11.3 percent

- Private inventory investment contributing 1.42 percentage points

There were negative contributions in IIQ2014:

- Imports growing at 11.3 percent, which is deduction from growth

- Federal government expenditures contracting at 0.9 percent

The BEA explains acceleration in real GDP growth in IIQ2014 by:

- Increase in the growth rate of PCE from 1.2 percent in IQ2014 to 2.5 percent in IIQ2014

- Acceleration of inventory investment contributing 1.42 percentage points in IIQ2014 after deducting 1.16 percentage points in IQ2014

- Growth of state and local government expenditures at 3.4 percent in IIQ2014 compared with contraction at 1.3 percent in IQ2014

- Growth of nonresidential fixed investment at 9.7 percent in IIQ2014 compared with growth at 1.6 percent in IQ2014

- Growth of residential fixed investment at 8.8 percent compared with contraction at 5.3 percent in IQ2014

- Growth of consumption of durable goods at 14.1 percent in IIQ2014 compared with 3.2 percent in IQ2014

- Growth of exports at 11.1 percent compared with contraction at 9.2 percent in IQ2014

- Acceleration of national defense expenditures at 0.9 percent in IIQ2014 compared with contraction at 4.0 percent in IQ2014

The BEA finds offsetting decelerating factors:

· Acceleration of growth of imports at 11.3 percent in IIQ2014 after growth at 2.2 percent in IQ2014

An important aspect of growth in the US is the decline in growth of real disposable personal income, or what is left after taxes and inflation, which increased at the rate of 0.9 percent in IIIQ2013 compared with a year earlier. Contraction of real disposable income of 1.9 percent in IVQ2013 relative to a year earlier is largely due to comparison with an artificially higher level in anticipations of income in Nov and Dec 2012 to avoid increases in taxes in 2013, an episode known as “fiscal cliff.” Real disposable personal income increased 2.4 percent in IQ2014 relative to a year earlier and 2.5 percent in IIQ2014 relative to a year earlier. The effects of financial repression, or zero interest, are vividly shown in the decline of the savings rate, or personal saving as percent of disposable income from 8.6 percent in IVQ2012 to 5.2 percent in IIIQ2013 and 4.4 percent in IVQ2013. The savings rate eased to 4.9 percent in IQ2014, increasing to 5.4 percent in IIQ2014. Anticipation of income in IVQ2012 to avoid higher taxes in 2013 caused increases in income and savings while higher payroll taxes in 2013 restricted income growth and savings in IQ2013. Zero interest rates induce risky investments with high leverage and can contract balance sheets of families, business and financial institutions when interest rates inevitably increase in the future. There is a tradeoff of weaker economy in the future when interest rates increase by meager growth in the present with forced consumption by zero interest rates. Microeconomics consists of the analysis of allocation of scarce resources to alternative and competing ends. Zero interest rates cloud he calculus of risk and returns in consumption and investment, disrupting decisions that maintain the economy in its long-term growth path.

Table I-9, US, Percentage Seasonally Adjusted Annual Equivalent Quarterly Rates of Increase, %

| IIQ 2013 | IIIQ 2012 | IVQ 2013 | IQ 2014 | IIQ 2014 | |

| GDP | 1.8 | 4.5 | 3.5 | -2.1 | 4.6 |

| PCE | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 2.5 |

| Durable Goods | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 14.1 |

| NRFI | 1.6 | 5.5 | 10.4 | 1.6 | 9.7 |

| RFI | 19.0 | 11.2 | -8.5 | -5.3 | 8.8 |

| Exports | 6.3 | 5.1 | 10.0 | -9.2 | 11.1 |

| Imports | 8.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 11.3 |

| GOV | 0.2 | 0.2 | -3.8 | -0.8 | 1.7 |

| Federal GOV | -3.5 | -1.2 | -10.4 | -0.1 | -0.9 |

| National Defense | -2.1 | 0.4 | -11.4 | -4.0 | 0.9 |

| Cont to GDP Growth % Points | -0.09 | 0.03 | -0.55 | -0.18 | 0.04 |

| State/Local GOV | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.6 | -1.3 | 3.4 |

| ∆ PI (PP) | 0.30 | 1.49 | -0.34 | -1.16 | 1.42 |

| Final Sales of Domestic Product | 1.5 | 3.0 | 3.9 | -1.0 | 3.2 |

| Gross Domestic Purchases | 2.2 | 3.8 | 2.3 | -0.4 | 4.8 |

| Prices Gross | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Prices of GDP | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| Prices of GDP Excluding Food and Energy | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Prices of PCE | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| Prices of PCE Excluding Food and Energy | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| Prices of Market Based PCE | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| Prices of Market Based PCE Excluding Food and Energy | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 |

| Real Disposable Personal Income* | 0.3 | 0.9 | -1.9 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Personal Saving As % Disposable Income | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.4 |

Note: PCE: personal consumption expenditures; NRFI: nonresidential fixed investment; RFI: residential fixed investment; GOV: government consumption expenditures and gross investment; ∆ PI: change in

private inventories; GDP - ∆ PI: final sales of domestic product; PP: percentage points; Personal savings rate: savings as percent of disposable income

*Percent change from quarter one year ago

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Percentage shares of GDP are shown in Table I-10. PCE (personal consumption expenditures) is equivalent to 68.5 percent of GDP and is under pressure with stagnant real disposable income, high levels of unemployment and underemployment and higher savings rates than before the global recession, temporarily interrupted by financial repression in the form of zero interest rates. Gross private domestic investment is also growing slowly even with about two trillion dollars in cash holdings by companies. In a slowing world economy, it may prove more difficult to grow exports faster than imports to generate higher growth. Bouts of risk aversion revalue the dollar relative to most currencies in the world as investors increase their holdings of dollar-denominated assets.

Table I-10, US, Percentage Shares of GDP, %

| IIQ2014 | |

| GDP | 100.0 |

| PCE | 68.5 |

| Goods | 22.9 |

| Durable | 7.5 |

| Nondurable | 15.4 |

| Services | 45.6 |

| Gross Private Domestic Investment | 16.4 |

| Fixed Investment | 15.8 |

| NRFI | 12.6 |

| Structures | 2.9 |

| Equipment & Software | 5.8 |

| Intellectual Property | 3.9 |

| RFI | 3.2 |

| Change in Private | 0.6 |

| Net Exports of Goods and Services | -3.2 |

| Exports | 13.5 |

| Goods | 9.4 |

| Services | 4.2 |

| Imports | 16.7 |

| Goods | 13.9 |

| Services | 2.8 |

| Government | 18.3 |

| Federal | 7.0 |

| National Defense | 4.4 |

| Nondefense | 2.6 |

| State and Local | 11.3 |

PCE: personal consumption expenditures; NRFI: nonresidential fixed investment; RFI: residential fixed investment

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table I-11 shows percentage point (PP) contributions to the annual levels of GDP growth in the earlier recessions 1958-1959, 1975-1976, 1982-1983 and 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. The data incorporate the new revisions released by the BEA on Jul 31, 2013. The most striking contrast is in the rates of growth of annual GDP in the expansion phases of 6.9 percent in 1959, 5.4 percent in 1976, and 4.6 percent in 1983 followed by 7.3 percent in 1984 and 4.2 percent in 1985. In contrast, GDP grew 2.5 percent in 2010 after six consecutive quarters of growth, 1.6 percent in 2011 after ten consecutive quarters of expansion, 2.3 percent in 2012 after 14 quarters of expansion and 2.2 percent in 2013 after 18 consecutive quarters of expansion. Annual levels also show much stronger growth of PCEs in the expansions after the earlier contractions than in the expansion after the global recession of 2007. Gross domestic investment was much stronger in the earlier expansions than in 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013.

Table I-11, US, Percentage Point Contributions to the Annual Growth Rate of GDP

| GDP | PCE | GDI | ∆ PI | Trade | GOV | |

| 1958 | -0.7 | 0.52 | -1.16 | -0.17 | -0.87 | 0.77 |

| 1959 | 6.9 | 3.49 | 2.82 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.59 |

| 1975 | -0.2 | 1.36 | -2.90 | -1.23 | 0.86 | 0.49 |

| 1976 | 5.4 | 3.41 | 2.91 | 1.37 | -1.05 | 0.12 |

| 1982 | -1.9 | 0.86 | -2.55 | -1.30 | -0.59 | 0.38 |

| 1983 | 4.6 | 3.54 | 1.60 | 0.28 | -1.32 | 0.81 |

| 1984 | 7.3 | 3.32 | 4.73 | 1.90 | -1.54 | 0.76 |

| 1985 | 4.2 | 3.25 | -0.01 | -1.03 | -0.39 | 1.38 |

| 1986 | 3.5 | 2.63 | 0.03 | -0.31 | -0.29 | 1.14 |

| 1987 | 3.5 | 2.14 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.63 |

| 2009 | -2.8 | -1.08 | -3.52 | -0.76 | 1.19 | 0.64 |

| 2010 | 2.5 | 1.32 | 1.66 | 1.45 | -0.46 | 0.02 |

| 2011 | 1.6 | 1.55 | 0.73 | -0.14 | -0.02 | -0.65 |

| 2012 | 2.3 | 1.25 | 1.33 | 0.15 | 0.04 | -0.30 |

| 2013 | 2.2 | 1.64 | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.22 | -0.39 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table I-12 provides more detail of the contributions to growth of GDP from 2009 to 2013 using annual-level data. PCEs contributed 1.32 PPs to GDP growth in 2010 of which 0.77 percentage points (PP) in goods and 0.55 PP in services. Gross private domestic investment (GPDI) deducted 3.52 PPs of GDP growth in 2009 of which -2.77 PPs by fixed investment and -0.76 PPs of inventory change (∆PI) and added 1.66 PPs of GPDI in 2010 of which 0.21 PPs of fixed investment and 1.45 PPs of inventory accumulation (∆PI). Trade, or exports of goods and services net of imports, contributed 1.19 PPs in 2009 of which exports deducted 1.07 PPs and imports added 2.26 PPs. In 2010, trade deducted 0.46 PPs with exports contributing 1.33 PPs and imports deducting 1.79 PPs likely benefitting from dollar revaluation. In 2009, government added 0.64 PP of which 0.44 PPs by the federal government and 0.20 PPs by state and local government; in 2010, government added 0.02 PPs of which 0.37 PPs by the federal government with state and local government deducting 0.35 PPs. Table I-12 provides the estimates for 2011, 2012 and 2013. PCE contributed 1.55 PPs in 2011 after 1.32 PPs in 2010. The contribution of PCE fell to 1.25 points in 2012 and increased to 1.64 PPs in 2013. The breakdown into goods and services is similar but with contributions in 2012 of 0.64 PPs of goods and 0.61 PPs of services. In 2013, goods contributed 0.78 PPs and services 0.86 PPs. Gross private domestic investment contributed 1.66 PPs in 2010 with 1.45 PPs of change of private inventories but the contribution of gross private domestic investment was only 0.73 PPs in 2011. The contribution of GDI in 2012 increased to 1.33 PPs with fixed investment increasing its contribution to 1.17 PPs and residential investment contributing 0.33 PPs for the first time since 2009. GDI contributed 1.33 PPs in 2012 with 1.17 PPs from fixed investment and 0.15 PPs from inventory change. Net exports of goods and services deducted marginally in 2011 with 0.02 PPs and added 0.04 PPs in 2012. Net trade contributed 0.22 PPs in 2013. The contribution of exports fell from 1.33 PPs in 2010 and 0.87 PPs in 2011 to only 0.44 PPs in 2012 and 0.41 PPs in 2013. Government deducted 0.65 PPs in 2011, 0.30 PPs in 2012 and 0.39 PPs in 2013. Demand weakened in 2013 with higher contribution of personal consumption expenditures of 1.64 PPs and of gross domestic investment of 0.76 PPs. Net trade contributed only 0.22 PPs. The expansion since IIIQ2009 has been characterized by weak contributions of aggregate demand, which is the sum of personal consumption expenditures plus gross private domestic investment. The US did not recover strongly from the global recessions as typical in past cyclical expansions. Recoveries tend to be more sluggish as expansions mature. At the margin in IVQ2011, the acceleration of expansion was driven by inventory accumulation instead of aggregate demand of consumption and investment. Growth of PCE was partly the result of burning savings because of financial repression, which may not be sustainable in the future while creating multiple distortions of resource allocation and growth restraint.

Table I-12, US, Contributions to Growth of Gross Domestic Product in Percentage Points

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| GDP Growth ∆% | -2.8 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) | -1.08 | 1.32 | 1.55 | 1.25 | 1.64 |

| Goods | -0.68 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Durable | -0.41 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.49 |

| Nondurable | -0.27 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.29 |

| Services | -0.40 | 0.55 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.86 |

| Gross Private Domestic Investment (GPDI) | -3.52 | 1.66 | 0.73 | 1.33 | 0.76 |

| Fixed Investment | -2.77 | 0.21 | 0.86 | 1.17 | 0.70 |

| Nonresidential | -2.04 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.37 |

| Structures | -0.70 | -0.49 | 0.06 | 0.32 | -0.01 |

| Equipment, software | -1.29 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.26 |

| Intellectual Property | -0.05 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Residential | -0.73 | -0.07 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Change Private Inventories | -0.76 | 1.45 | -0.14 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| Net Exports of Goods and Services | 1.19 | -0.46 | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.22 |

| Exports | -1.07 | 1.33 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 0.41 |

| Goods | -1.03 | 1.08 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| Services | -0.04 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| Imports | 2.26 | -1.79 | -0.89 | -0.40 | -0.19 |

| Goods | 2.15 | -1.69 | -0.78 | -0.30 | -0.13 |

| Services | 0.10 | -0.10 | -0.11 | -0.10 | -0.06 |

| Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment | 0.64 | 0.02 | -0.65 | -0.30 | -0.39 |

| Federal | 0.44 | 0.37 | -0.24 | -0.15 | -0.45 |

| National Defense | 0.27 | 0.18 | -0.13 | -0.18 | -0.33 |

| Nondefense | 0.17 | 0.19 | -0.11 | 0.03 | -0.12 |

| State and Local | 0.20 | -0.35 | -0.41 | -0.15 | 0.06 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Manufacturing jobs not seasonally adjusted increased 166,000 from Aug 2013 to

Aug 2014 or at the average monthly rate of 13,833. There are effects of the weaker economy and international trade together with the yearly adjustment of labor statistics. Industrial production decreased 0.1 percent in Aug 2014 after increasing 0.2 percent in Jul 2014 and increasing 0.3 percent in Jun 2014, with all data seasonally adjusted. The Federal Reserve completed its annual revision of industrial production and capacity utilization on Mar 28, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm). The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):