Dollar Revaluation, Twenty-One Million Unemployed or Underemployed in the Lost Economic Cycle of the Global Recession with Economic Growth Underperforming Below Trend Worldwide, Job Creation, Cyclically Stagnating Real Wages, Cyclically Stagnating Real Disposable Income per Capita, Financial Repression, United States Housing, United States International Trade, Decline of United States Homeownership, World Cyclical Slow Growth, Government Intervention in Globalization, and Global Recession Risk

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019

I Twenty-One Million Unemployed or Underemployed

IA1 Summary of the Employment Situation

IA2 Number of People in Job Stress

IA3 Long-term and Cyclical Comparison of Employment

IA4 Job Creation

II Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IIB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

IIA United States Housing Collapse

IIA1 Sales of New Houses

IIA2 United States House Prices

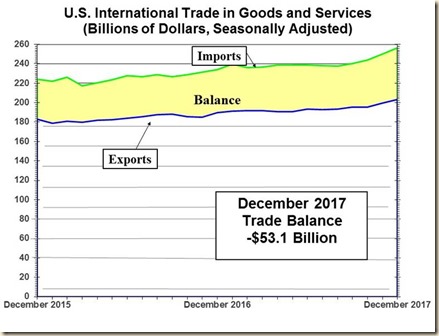

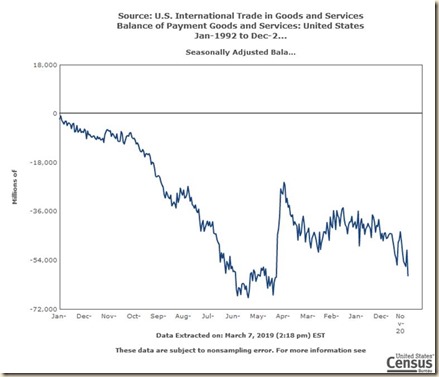

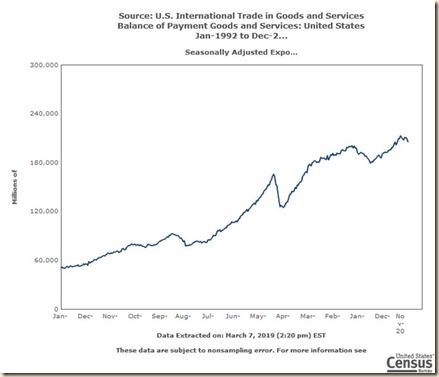

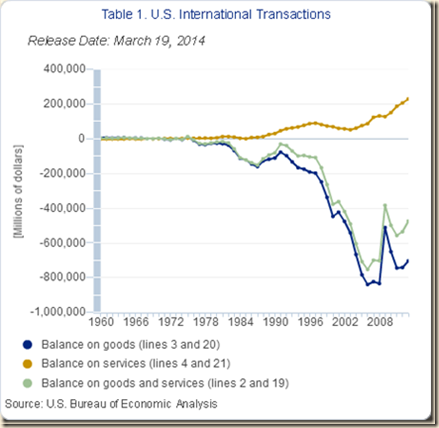

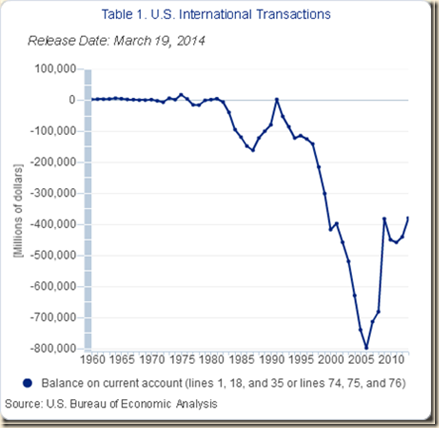

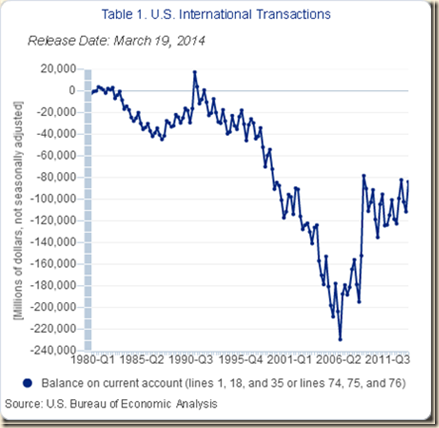

IIC United States International Trade

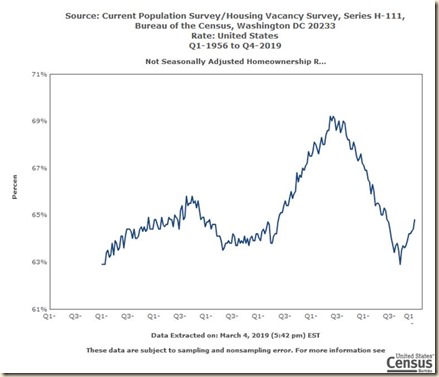

IID Decline of United States Homeownership

III World Financial Turbulence

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

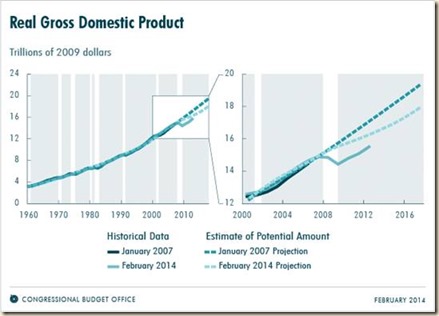

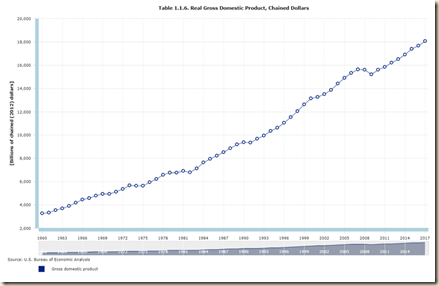

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

II I United States Housing Collapse. Data and other information continue to provide depressed conditions in the US housing market in a longer perspective, with recent improvement at the margin. Table IIB-1 shows sales of new houses in the US at seasonally adjusted annual equivalent rate (SAAR). The US Census Bureau revised all seasonally-adjusted new house sales from 2013 to 2018 with the report for Apr 2018 on May 23, 2018 (https://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/pdf/newressales.pdf). House sales fell in 39 of 96 months from Jan 2011 to Dec 2018 with monthly declines of 5 in 2011, 4 in 2012, 5 in 2013, 6 in 2014, 3 in 2015, 6 in 2016, 4 in 2017 and 6 in 2018. In Jan-Apr 2012, house sales increased at the annual equivalent rate of 11.8 percent and at 22.3 percent in May-Sep 2012. There was significant strength in Sep-Dec 2011 with annual equivalent rate of 48.4 percent. Sales of new houses fell at 7.0 percent in Oct 2012 with increase of 9.5 percent in Nov 2012. Sales of new houses rebounded 11.8 percent in Jan 2013 with annual equivalent rate of 55.7 percent from Oct 2012 to Jan 2013 because of the increase at 11.8 percent in Jan 2013. New house sales decreased at annual equivalent 3.0 percent in Feb-Mar 2013. New house sales weakened, decreasing at 3.1 percent in annual equivalent from Apr to Dec 2013 with significant volatility illustrated by decline of 20.2 percent in Jul 2013 and increase of 10.2 percent in Oct 2013. New house sales fell 2.9 percent in Dec 2013. New house sales increased 2.8 percent in Jan 2014 and fell 3.6 percent in Feb 2014, decreasing 4.7 percent in Mar 2014. New house sales decreased 2.2 percent in Apr 2014 and increased 13.0 percent in May 2014. New house sales fell 8.0 percent in Jun 2014 and decreased 3.4 percent in Jul 2014. New house sales jumped 13.2 percent in Aug 2014 and increased 2.4 percent in Sep 2014. New House sales increased 1.3 percent in Oct 2014 and fell 5.9 percent in Nov 2014. House sales fell at the annual equivalent rate of 9.2 percent in Sep-Nov 2014. New house sales increased 9.9 percent in Dec 2014 and increased 7.0 percent in Jan 2015. Sales of new houses increased 6.5 percent in Feb

2015 and fell 12.8 percent in Mar 2015. House sales increased 3.7 percent in Apr 2015. The annual equivalent rate in Dec 2014-Apr 2015 was 34.8 percent. New house sales increased 0.2 percent in May 2015 and fell 6.0 percent in Jun 2015, increasing 5.1 percent in Jul 2015. New house sales fell at annual equivalent 4.0 percent in May-Jul 2015. New house sales increased 3.4 percent in Aug 2015 and fell 11.5 percent in Sep 2015. New house sales decreased at annual equivalent 41.3 percent in Aug-Sep 2015. New house sales increased 4.4 percent in Oct 2015 and increased 5.9 percent in Nov 2015, increasing 6.0 percent in Dec 2015. New house sales increased at the annual equivalent rate of 88.6 percent in Oct-Dec 2015. New house sales decreased 2.8 percent in Jan 2016 at the annual equivalent rate of minus 28.9 percent. New house sales increased 1.5 percent in Feb 2016 and increased 2.1 percent in Mar 2016. New house sales jumped at 5.2 percent in Apr 2016. New house sales increased at the annual equivalent rate of 41.3 percent in Feb-Apr 2016. New house sales decreased 1.4 percent in May 2016 and increased 0.4 percent in Jun 2016. New house sales jumped 12.9 percent in Jul 2016. New house sales increased at the annual equivalent rate of 56.0 percent in May-Jul 2016. New house sales fell 9.5 percent in Aug 2016 and decreased 1.0 percent in Sep 2016, increasing 1.2 percent in Oct 2016. New house sales fell at the annual equivalent rate of minus 32.4 percent in Aug-Oct 2016. New house sales decreased at 0.9 percent in Nov 2016 and fell at 3.9 percent in Dec 2016. New house sales fell at 25.4 percent annual equivalent in Nov-Dec 2016. New house sales increased at 9.2 percent in Jan 2017 and increased at 3.7 percent in Feb 2017. New house sales increased at 100.9 percent in Jan-Feb 2017. New house sales increased at 4.0 percent in Mar 2017 and fell at 7.8 percent in Apr 2017. New house sales decreased at annual equivalent 22.3 percent in Mar-Apr 2017. New house sales increased at 1.9 percent in May 2017 and increased at 2.0 percent in Jun 2017. New house sales increased at annual equivalent 26.1 percent in May-Jun 2017. New house sales decreased at 9.7 percent in Jul 2017 and increased at 0.4 percent in Aug 2017, increasing at 14.2 percent in Sep 2017. New house sales increased at annual equivalent 14.9 percent in Jul-Sep 2017. New house sales decreased at 3.0 percent in Oct 2017. New house sales increased at 15.2 percent in Nov 2017. New house sales increased at annual equivalent 94.7 percent in Oct-Nov 2017. New house sales decreased at 10.7 percent in Dec 2017 and decreased at 0.5 percent in Jan 2018. New house sales decreased at annual equivalent 50.8 percent in Dec 2017-Jan 2018. New house sales increased at 4.7 percent in Feb 2018, increasing at 1.4 percent in Mar 2018. New house sales increased at 43.2 percent in Feb-Mar 2018. New house sales decreased at 5.8 percent in Apr 2018 and increased at 3.2 percent in May 2018. New House sales decreased at annual equivalent 15.6 percent in Apr-May 2018. New house sales decreased at 6.3 percent in Jun 2018 and decreased at 1.0 percent in Jul 2018. New House sales decreased at annual equivalent 36.3 percent in Jun-Jul 2018. New house sales decreased at 0.8 percent in Aug 2018 and increased at 1.3 percent in Sep 2018. New house sales increased at annual equivalent 3.0 percent in Aug-Sep 2018. New house sales fell at 9.9 percent in Oct 2018 and increased at 9.1 percent in Nov 2018, increasing at 3.7 percent in Dec 2018. New house sales increased at annual equivalent 8.0 percent in Oct-Dec 2018. There are wide monthly oscillations. Robbie Whelan and Conor Dougherty, writing on “Builders fuel home sale rise,” on Feb 26, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324338604578327982067761860.html), analyze how builders have provided financial assistance to home buyers, including those short of cash and with weaker credit background, explaining the rise in new home sales and the highest gap between prices of new and existing houses. The 30-year conventional mortgage rate increased from 3.40 on Apr 25, 2013 to 4.58 percent on Aug 22, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm), which could also be a factor in recent weakness with improvement after the rate fell to 4.26 in Nov 2013. The conventional mortgage rate rose to 4.48 percent on Dec 26, 2013 and fell to 4.32 percent on Jan 30, 2014. The conventional mortgage rate increased to 4.37 percent on Feb 26, 2014 and 4.40 percent on Mar 27, 2014. The conventional mortgage rate fell to 4.14 percent on Apr 22, 2014, stabilizing at 4.14 on Jun 26, 2014. The conventional mortgage rate stood at 3.93 percent on Aug 20, 2015 and at 3.91 percent on Sep 17, 2015. The conventional mortgage rate was at 3.79 percent on Oct 22, 2015. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.97 percent on Nov 20, 2015. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.97 percent on Dec 18, 2015, and 3.92 percent on Jan 14, 2016. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.65 percent on Feb 19, 2016. The commercial mortgage rate was 3.73 percent on Mar 17, 2016 and 3.59 percent on Apr 21, 2016. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.58 on May 19, 2016. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.54 percent on Jun 19, 2016 and 3.45 percent on Jul 21, 2016. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.43 percent on Aug 18, 2016 and 3.48 percent on Sep 22, 2016. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.94 on Nov 17, 2016 and 4.30 percent on Dec 22. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.19 percent on Jan 26, 2017 and 4.15 percent on Feb 17, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.1 percent on Mar 16, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.97 percent on Apr 20, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.05 percent on May 18, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.90 percent on Jun 22, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.96 percent on Jul 20, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.90 percent on Aug 18, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.83 percent on Sep 21, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.88 percent on Oct 20, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 3.92 percent on Nov 22, 2017 and 3.94 on Dec 21, 2017. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.04 percent on Jan 18, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.40 percent on Feb 22, 2018. The conventional rate was 4.43 percent on Mar 1, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.45 percent on Mar 22, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.47 on Apr 19, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.87 percent in May 31, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.57 percent on Jun 21, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.52 percent on Jul 19, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.53 percent on Aug 16, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.65 percent on Sep 20, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.85 percent on Oct 18, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.81 percent on Nov 21, 2018. The conventional mortgage rate was 4.35 percent in Feb 2019. The conventional mortgage rate measured in a survey by Freddie Mac (http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/ http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/abtpmms.htm) is the “interest rate a lender would charge to lend mortgage money to a qualified borrower.

| SA Annual Rate | ∆% | |

| Dec 2018 | 621 | 3.7 |

| Nov | 599 | 9.1 |

| Oct | 549 | -9.9 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Dec | 8.0 | |

| Sep | 609 | 1.3 |

| Aug | 601 | -0.8 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Sep | 3.0 | |

| Jul | 606 | -1.0 |

| Jun | 612 | -6.3 |

| AE ∆% Jun-Jul | -36.3 | |

| May | 653 | 3.2 |

| Apr | 633 | -5.8 |

| AE ∆% Apr-May | -15.6 | |

| Mar | 672 | 1.4 |

| Feb | 663 | 4.7 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Mar | 43.2 | |

| Jan | 633 | -0.5 |

| Dec 2017 | 636 | -10.7 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Jan | -50.8 | |

| Nov | 712 | 15.2 |

| Oct | 618 | -3.0 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Nov | 94.7 | |

| Sep | 637 | 14.2 |

| Aug | 558 | 0.4 |

| Jul | 556 | -9.7 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Sep | 14.9 | |

| Jun | 616 | 2.0 |

| May | 604 | 1.9 |

| AE ∆% May -Jun | 26.1 | |

| Apr | 593 | -7.8 |

| Mar | 643 | 4.0 |

| AE ∆% Mar-Apr | -22.3 | |

| Feb | 618 | 3.7 |

| Jan | 596 | 9.2 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Feb | 100.9 | |

| Dec 2016 | 546 | -3.9 |

| Nov | 568 | -0.9 |

| AE ∆% Nov-Dec | -25.4 | |

| Oct | 573 | 1.2 |

| Sep | 566 | -1.0 |

| Aug | 572 | -9.5 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Oct | -32.4 | |

| Jul | 632 | 12.9 |

| Jun | 560 | 0.4 |

| May | 558 | -1.4 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 56.0 | |

| Apr | 566 | 5.2 |

| Mar | 538 | 2.1 |

| Feb | 527 | 1.5 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Apr | 41.3 | |

| Jan | 519 | -2.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan | -28.9 | |

| Dec 2015 | 534 | 6.0 |

| Nov | 504 | 5.9 |

| Oct | 476 | 4.4 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Dec | 88.6 | |

| Sep | 456 | -11.5 |

| Aug | 515 | 3.4 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Sep | -41.3 | |

| Jul | 498 | 5.1 |

| Jun | 474 | -6.0 |

| May | 504 | 0.2 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | -4.0 | |

| Apr | 503 | 3.7 |

| Mar | 485 | -12.8 |

| Feb | 556 | 6.5 |

| Jan | 522 | 7.0 |

| Dec 2014 | 488 | 9.9 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Apr | 34.8 | |

| Nov | 444 | -5.9 |

| Oct | 472 | 1.3 |

| Sep | 466 | 2.4 |

| AE ∆% Sep-Nov | -9.2 | |

| Aug | 455 | 13.2 |

| Jul | 402 | -3.4 |

| Jun | 416 | -8.0 |

| May | 452 | 13.0 |

| Apr | 400 | -2.2 |

| Mar | 409 | -4.7 |

| Feb | 429 | -3.6 |

| Jan | 445 | 2.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Aug | 7.6 | |

| Dec 2013 | 433 | -2.9 |

| Nov | 446 | 0.5 |

| Oct | 444 | 10.2 |

| Sep | 403 | 5.8 |

| Aug | 381 | 1.6 |

| Jul | 375 | -20.2 |

| Jun | 470 | 9.8 |

| May | 428 | -2.9 |

| Apr | 441 | -0.7 |

| AE ∆% Apr-Dec | -3.1 | |

| Mar | 444 | -0.7 |

| Feb | 447 | 0.2 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Mar | -3.0 | |

| Jan | 446 | 11.8 |

| Dec 2012 | 399 | 1.8 |

| Nov | 392 | 9.5 |

| Oct | 358 | -7.0 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Jan | 55.7 | |

| Sep | 385 | 2.7 |

| Aug | 375 | 1.6 |

| Jul | 369 | 2.5 |

| Jun | 360 | -2.7 |

| May | 370 | 4.5 |

| AE ∆% May-Sep | 22.3 | |

| Apr | 354 | 0.0 |

| Mar | 354 | -3.3 |

| Feb | 366 | 9.3 |

| Jan | 335 | -1.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 11.8 | |

| Dec 2011 | 341 | 4.0 |

| Nov | 328 | 3.8 |

| Oct | 316 | 3.9 |

| Sep | 304 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% Sep-Dec | 48.4 | |

| Aug | 299 | 1.0 |

| Jul | 296 | -1.7 |

| Jun | 301 | -1.3 |

| May | 305 | -1.6 |

| AE ∆% May-Aug | -10.3 | |

| Apr | 310 | 3.3 |

| Mar | 300 | 11.1 |

| Feb | 270 | -12.1 |

| Jan | 307 | -5.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | -14.2 | |

| Dec 2010 | 326 | 13.6 |

AE: Annual Equivalent

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

There is additional information of the report of new house sales in Table IIB-2. The stock of unsold houses fell from rates of 6 to 8 percent of sales in 2011 to 4 to 5 percent in 2013 and 6.6 percent in Dec 2018. Robbie Whelan and Conor Dougherty, writing on “Builders fuel home sale rise,” on Feb 26, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324338604578327982067761860.html), find that inventories of houses have declined as investors acquire distressed houses of higher quality. Median and average house prices oscillate. In Dec 2018, median prices of new houses sold not seasonally adjusted (NSA) increased 5.0 percent after decreasing 6.5 percent in

Nov 2018. Average prices increased 5.4 percent in Dec 2018 and decreased 9.1 percent in Nov 2018. Between Dec 2010 and Dec 2018, median prices increased 32.1 percent, with increases of 6.0 percent in Feb 2016, 4.9 percent in Nov 2015, 2.2 percent in Sep 2015, 13.6 percent in Oct 2014, 4.0 percent in Aug 2014, 4.0 percent in May 2014 and 5.2 percent in Mar 2014. Average prices increased 29.2 percent between Dec 2010 and Dec 2018, with increases of 5.1 percent in Mar 2016, 4.0 percent in Sep 2015, 4.4 percent in Jul 2015 and 18.3 percent in Oct 2014. Between Dec 2010 and Dec 2012, median prices increased 7.1 percent and average prices increased 2.6 percent. Price increases concentrated in 2012 with increase of median prices of 18.2 percent from Dec 2011 to Dec 2012 and of average prices of 13.8 percent. Median prices increased 16.7 percent from Dec 2012 to Dec 2014, with increase of 13.6 percent in Oct 2014, while average prices increased 24.7 percent, with increase of 18.3 percent in Oct 2014. Median prices decreased 1.5 percent from Dec 2014 to Dec 2015 while average prices fell 5.5 percent. Median prices increased 10.1 percent from Dec 2015 to Dec 2016 while average prices increased 8.5 percent. Median prices increased 5.0 percent from Dec 2016 to Dec 2017 while average prices increased 5.3 percent. Median prices decreased 7.2 percent from Dec 2017 to Dec 2018 while average prices decreased 6.4 percent. Robbie Whelan, writing on “New homes hit record as builders cap supply,” on May 24, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323475304578500973445311276.html?mod=WSJ_economy_LeftTopHighlights), finds that homebuilders are continuing to restrict the number of new homes for sale. Restriction of available new homes for sale increases prices paid by buyers.

Table IIB-2, US, New House Stocks and Median and Average New Homes Sales Price

| Unsold* | Median | Month | Average New House Sales Price USD | Month | |

| Dec 2018 | 6.6 | 318,600 | 5.0 | 377,000 | 5.4 |

| Nov | 6.7 | 303,500 | -6.5 | 357,600 | -9.1 |

| Oct | 7.2 | 324,700 | -1.1 | 393,300 | 1.8 |

| Sep | 6.3 | 328,300 | 2.1 | 386,400 | 1.4 |

| Aug | 6.3 | 321,400 | -1.9 | 380,900 | -2.9 |

| Jul | 6.2 | 327,500 | 5.5 | 392,300 | 6.0 |

| Jun | 6.0 | 310,500 | -2.0 | 370,100 | -0.7 |

| May | 5.5 | 316,700 | 0.7 | 372,600 | -3.2 |

| Apr | 5.7 | 314,400 | -6.3 | 385,100 | 4.3 |

| Mar | 5.3 | 335,400 | 2.5 | 369,200 | -1.2 |

| Feb | 5.4 | 327,200 | -0.7 | 373,600 | -1.1 |

| Jan | 5.6 | 329,600 | -4.0 | 377,800 | -6.2 |

| Dec 2017 | 5.5 | 343,300 | 0.0 | 402,900 | 3.7 |

| Nov | 4.9 | 343,400 | 7.5 | 388,500 | -1.4 |

| Oct | 5.6 | 319,500 | -3.6 | 394,000 | 3.9 |

| Sep | 5.3 | 331,500 | 5.5 | 379,300 | 2.7 |

| Aug | 6.0 | 314,200 | -2.7 | 369,200 | -0.9 |

| Jul | 6.0 | 322,900 | 2.4 | 372,400 | 0.5 |

| Jun | 5.3 | 315,200 | -2.6 | 370,600 | -2.1 |

| May | 5.4 | 323,600 | 4.0 | 378,400 | 3.4 |

| Apr | 5.4 | 311,100 | -3.3 | 365,800 | -4.8 |

| Mar | 5.0 | 321,700 | 8.0 | 384,400 | 3.8 |

| Feb | 5.1 | 298,000 | -5.5 | 370,500 | 3.6 |

| Jan | 5.3 | 315,200 | -3.6 | 357,700 | -6.5 |

| Dec 2016 | 5.6 | 327,000 | 3.8 | 382,500 | 5.3 |

| Nov | 5.3 | 315,000 | 4.0 | 363,400 | 3.2 |

| Oct | 5.2 | 302,800 | -3.8 | 352,200 | -3.8 |

| Sep | 5.2 | 314,800 | 5.3 | 366,100 | 3.1 |

| Aug | 5.0 | 298,900 | 0.5 | 355,100 | 0.6 |

| Jul | 4.5 | 297,400 | -4.4 | 353,000 | -1.3 |

| Jun | 5.2 | 311,200 | 5.4 | 357,800 | 2.3 |

| May | 5.2 | 295,200 | -7.3 | 349,700 | -5.3 |

| Apr | 5.1 | 318,300 | 5.0 | 369,300 | 2.9 |

| Mar | 5.4 | 303,200 | -0.9 | 359,000 | 5.1 |

| Feb | 5.4 | 305,800 | 6.0 | 341,700 | -5.4 |

| Jan | 5.5 | 288,400 | -2.9 | 361,200 | 2.5 |

| Dec 2015 | 5.2 | 297,100 | -5.0 | 352,500 | -5.5 |

| Nov | 5.5 | 312,600 | 4.9 | 373,200 | 1.2 |

| Oct | 5.7 | 298,000 | -0.5 | 368,900 | 3.3 |

| Sep | 5.9 | 299,500 | 2.2 | 357,200 | 4.0 |

| Aug | 5.1 | 293,000 | 0.2 | 343,300 | 0.6 |

| Jul | 5.2 | 292,300 | 2.5 | 341,200 | 4.4 |

| Jun | 5.5 | 285,100 | -0.8 | 326,900 | -2.8 |

| May | 5.0 | 287,500 | -2.4 | 336,200 | -1.2 |

| Apr | 4.9 | 294,500 | 2.8 | 340,400 | -2.5 |

| Mar | 5.1 | 286,600 | 0.0 | 349,300 | 0.9 |

| Feb | 4.4 | 286,600 | -1.8 | 346,300 | -0.6 |

| Jan | 4.8 | 292,000 | -3.2 | 348,300 | -6.7 |

| Dec 2014 | 5.2 | 301,500 | 1.1 | 373,200 | 7.0 |

| Nov | 5.7 | 298,300 | 0.4 | 348,900 | -7.6 |

| Oct | 5.3 | 297,000 | 13.6 | 377,500 | 18.3 |

| Sep | 5.4 | 261,500 | -10.4 | 319,100 | -10.4 |

| Aug | 5.5 | 291,700 | 4.0 | 356,200 | 3.2 |

| Jul | 6.1 | 280,400 | -2.3 | 345,200 | 2.1 |

| Jun | 5.7 | 287,000 | 0.5 | 338,100 | 4.5 |

| May | 5.2 | 285,600 | 4.0 | 323,500 | -0.5 |

| Apr | 5.7 | 274,500 | -2.8 | 325,100 | -1.9 |

| Mar | 5.6 | 282,300 | 5.2 | 331,500 | 1.7 |

| Feb | 5.2 | 268,400 | -0.5 | 325,900 | -3.4 |

| Jan | 5.1 | 269,800 | -2.1 | 337,300 | 5.0 |

| Dec 2013 | 5.2 | 275,500 | -0.6 | 321,200 | -4.3 |

| Nov | 5.0 | 277,100 | 4.8 | 335,600 | 0.0 |

| Oct | 4.9 | 264,300 | -2.0 | 335,700 | 4.4 |

| Sep | 5.4 | 269,800 | 5.7 | 321,400 | 3.4 |

| Aug | 5.5 | 255,300 | -2.6 | 310,800 | -5.8 |

| Jul | 5.5 | 262,200 | 0.9 | 329,900 | 7.8 |

| Jun | 4.1 | 259,800 | -1.5 | 306,100 | -2.5 |

| May | 4.6 | 263,700 | -5.6 | 314,000 | -6.8 |

| Apr | 4.4 | 279,300 | 8.5 | 337,000 | 12.3 |

| Mar | 4.2 | 257,500 | -2.9 | 300,200 | -3.9 |

| Feb | 4.1 | 265,100 | 5.4 | 312,500 | 1.8 |

| Jan | 4.0 | 251,500 | -2.6 | 306,900 | 2.6 |

| Dec 2012 | 4.5 | 258,300 | 5.4 | 299,200 | 2.9 |

| Nov | 4.6 | 245,000 | -0.9 | 290,700 | 1.9 |

| Oct | 4.9 | 247,200 | -2.9 | 285,400 | -4.1 |

| Sep | 4.5 | 254,600 | 0.6 | 297,700 | -2.6 |

| Aug | 4.6 | 253,200 | 6.7 | 305,500 | 8.2 |

| Jul | 4.6 | 237,400 | 2.1 | 282,300 | 3.9 |

| Jun | 4.8 | 232,600 | -2.8 | 271,800 | -3.2 |

| May | 4.7 | 239,200 | 1.2 | 280,900 | -2.4 |

| Apr | 4.9 | 236,400 | -1.4 | 287,900 | 1.5 |

| Mar | 4.9 | 239,800 | 0.0 | 283,600 | 3.5 |

| Feb | 4.8 | 239,900 | 8.2 | 274,000 | 3.1 |

| Jan | 5.3 | 221,700 | 1.4 | 265,700 | 1.1 |

| Dec 2011 | 5.3 | 218,600 | 2.0 | 262,900 | 5.2 |

| Nov | 5.7 | 214,300 | -4.7 | 250,000 | -3.2 |

| Oct | 6.0 | 224,800 | 3.6 | 258,300 | 1.1 |

| Sep | 6.3 | 217,000 | -1.2 | 255,400 | -1.5 |

| Aug | 6.5 | 219,600 | -4.5 | 259,300 | -4.1 |

| Jul | 6.7 | 229,900 | -4.3 | 270,300 | -1.0 |

| Jun | 6.6 | 240,200 | 8.2 | 273,100 | 4.0 |

| May | 6.6 | 222,000 | -1.2 | 262,700 | -2.3 |

| Apr | 6.7 | 224,700 | 1.9 | 268,900 | 3.1 |

| Mar | 7.2 | 220,500 | 0.2 | 260,800 | -0.8 |

| Feb | 8.1 | 220,100 | -8.3 | 262,800 | -4.7 |

| Jan | 7.3 | 240,100 | -0.5 | 275,700 | -5.5 |

| Dec 2010 | 7.0 | 241,200 | 9.8 | 291,700 | 3.5 |

*Percent of new houses for sale relative to houses sold

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

The depressed level of residential construction and new house sales in the US is evident in Table IIB-3 providing new house sales not seasonally adjusted in Jan-Dec of various years. New house sales increased 1.5 percent from Jan-Dec 2017 to Jan-Dec 2018. Sales of new houses are higher in Jan-Dec 2018 relative to Jan-Dec 2016 with increase of 10.9 percent. Sales of new houses are higher in Jan-Dec 2018 relative to Jan-Dec 2015 with increase of 24.2 percent. Sales of new houses in Jan-Dec 2018 are substantially lower than in many years between 1971 and 2018 except for the years from 2008 to 2017. There are several other increases of 41.7 percent relative to 2014, 45.0 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2013, 68.6 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2012, 103.9 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2011, 93.2 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2010 and 66.3 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2009. New house sales in Jan-Dec 2018 are 28.2 percent higher than in Jan-Dec 2008. Sales of new houses in Jan-Dec 2018 are lower by 19.8 percent relative to Jan-Dec 2007, 40.9 percent relative to 2006, 51.5 percent relative to 2005 and 48.3 percent relative to 2004. The housing boom peaked in 2005 and 2006 when increases in fed funds rates to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006 from 1.0 percent in Jun 2004 affected subprime mortgages that were programmed for refinancing in two or three years on the expectation that price increases forever would raise home equity. Higher home equity would permit refinancing under feasible mortgages incorporating full payment of principal and interest (Gorton 2009EFM; see other references in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html). Sales of new houses in Jan-Dec 2018 relative to the same period in 2003 fell 42.8 percent and 36.0 percent relative to the same period in 2002. Similar percentage declines are also for 2018 relative to years from 2000 to 2004. Sales of new houses in Jan-Dec 2018 decreased 6.5 per cent relative to the same period in 1995. The population of the US was 179.3 million in 1960 and 281.4 million in 2000 (Hobbs and Stoops 2002, 16). Detailed historical census reports are available from the US Census Bureau at (http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/hiscendata.html). The estimate of the US population is 418.8 million in 2015. The US population increased by 133.6 percent from 1960 to 2015. The final row of Table IIB-3 reveals catastrophic data: sales of new houses in Jan-Dec 2018 of 622 thousand units are lower by 13.4 percent relative to 718 thousand units of houses sold in Jan-Dec 1972, which is the ninth year when data become available in 1963. The civilian noninstitutional population increased from 122.416 million in 1963 to 257.791 million in 2018, or 110.6 percent (http://www.bls.gov/data/). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines the civilian noninstitutional population (http://www.bls.gov/lau/rdscnp16.htm#cnp): “The civilian noninstitutional population consists of persons 16 years of age and older residing in the 50 States and the District of Columbia who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities and homes for the aged) and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces.”

Table IIB-3, US, Sales of New Houses Not Seasonally Adjusted, Thousands and %

| Jan-Dec 2018 | 622 |

| Jan-Dec 2017 | 613 |

| Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2017 | 1.5 |

| Jan-Dec 2016 | 561 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2016 | 10.9 |

| Jan-Dec 2015 | 501 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2015 | 24.2 |

| Jan-Dec 2014 | 439 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2014 | 41.7 |

| Jan-Dec 2013 | 429 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2013 | 45.0 |

| Jan-Dec 2012 | 369 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2012 | 68.6 |

| Jan-Dec 2011 | 305 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | 103.9 |

| Jan-Dec 2010 | 322 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | 93.2 |

| Jan-Dec 2009 | 374 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | 66.3 |

| Jan-Dec 2008 | 485 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | 28.2 |

| Jan-Dec 2007 | 776 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2007 | -19.8 |

| Jan-Dec 2006 | 1052 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2006 | -40.9 |

| Jan-Dec 2005 | 1283 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2005 | -51.5 |

| Jan-Dec 2004 | 1203 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -48.3 |

| Jan-Dec 2003 | 1088 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -42.8 |

| Jan-Dec 2002 | 972 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -36.0 |

| Jan-Dec 2001 | 909 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -31.6 |

| Jan-Dec 2000 | 877 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/Jan-Dec 2000 | -29.1 |

| Jan-Dec 1995 | 665 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -6.5 |

| Jan-Dec 1972 | 671 |

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2018/ | -13.4 |

*Computed using unrounded data

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

The revised level of 306 thousand new houses sold in 2011 is the lowest since 560 thousand in 1963 in the 53 years of available data while the level of 368 thousand in 2012 is only higher than 323 thousand in 2010. The level of sales of new houses of 437 thousand in 2014 is the lowest from 1963 to 2009 with exception of 412 thousand in 1982 and 436 thousand in 1981. The population of the US increased 129.4 million from 179.3 million in 1960 to 308.7 million in 2010, or 72.2 percent. The estimate of the US population is 418.8 million in 2015. The US population increased 133.6 percent from 1960 to 2015. The civilian noninstitutional population increased from 122.416 million in 1963 to 257.791 million in 2018, or 110.6 percent (http://www.bls.gov/data/). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines the civilian noninstitutional population (http://www.bls.gov/lau/rdscnp16.htm#cnp): “The civilian noninstitutional population consists of persons 16 years of age and older residing in the 50 States and the District of Columbia who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities and homes for the aged) and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces.”

The civilian noninstitutional population is the universe of the labor force. In fact, there is no year from 1963 to 2013 in Table IIA-4 with sales of new houses below 400 thousand except for the immediately preceding years of 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012.

Table IIB-4, US, New Houses Sold, NSA Thousands

| Period | Sold During Period |

| 1963 | 560 |

| 1964 | 565 |

| 1965 | 575 |

| 1966 | 461 |

| 1967 | 487 |

| 1968 | 490 |

| 1969 | 448 |

| 1970 | 485 |

| 1971 | 656 |

| 1972 | 718 |

| 1973 | 634 |

| 1974 | 519 |

| 1975 | 549 |

| 1976 | 646 |

| 1977 | 819 |

| 1978 | 817 |

| 1979 | 709 |

| 1980 | 545 |

| 1981 | 436 |

| 1982 | 412 |

| 1983 | 623 |

| 1984 | 639 |

| 1985 | 688 |

| 1986 | 750 |

| 1987 | 671 |

| 1988 | 676 |

| 1989 | 650 |

| 1990 | 534 |

| 1991 | 509 |

| 1992 | 610 |

| 1993 | 666 |

| 1994 | 670 |

| 1995 | 667 |

| 1996 | 757 |

| 1997 | 804 |

| 1998 | 886 |

| 1999 | 880 |

| 2000 | 877 |

| 2001 | 908 |

| 2002 | 973 |

| 2003 | 1,086 |

| 2004 | 1,203 |

| 2005 | 1,283 |

| 2006 | 1,051 |

| 2007 | 776 |

| 2008 | 485 |

| 2009 | 375 |

| 2010 | 323 |

| 2011 | 306 |

| 2012 | 368 |

| 2013 | 429 |

| 2014 | 437 |

| 2015 | 501 |

| 2016 | 561 |

| 2017 | 613 |

| 2018 | 622 |

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

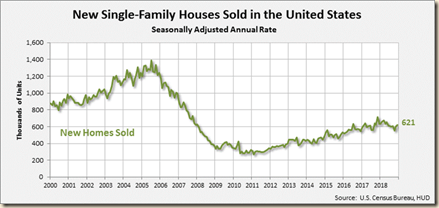

Chart IIB-1 of the US Bureau of the Census shows the sharp decline of sales of new houses in the US. Sales rose temporarily until about mid 2010 but then declined to a lower plateau followed by increase, stability and new oscillating increase. There is decrease in the final segment.

Chart IIB-1, US, New One-Family Houses Sold in the US, SAAR (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate)

Source: US Census Bureau

https://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/img/c25_curr.gif

Between 1991 and 2001, sales of new houses rose 78.4 percent at the average yearly rate of 6.0 percent, as shown in Table IB-5. Between 1995 and 2005 sales of new houses increased 92.4 percent at the yearly rate of 6.8 percent. There are similar rates in all years from 2000 to 2005. The boom in housing construction and sales began in the 1980s and 1990s. The collapse of real estate culminated several decades of housing subsidies and policies to lower mortgage rates and borrowing terms (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009b), 42-8). Sales of new houses sold in 2018 fell 6.7 percent relative to the same period in 1995 and 51.5 percent relative to 2005.

| ∆% | Average Yearly % Rate | |

| 1963-2018 | 11.1 | 0.2 |

| 1991-2001 | 78.4 | 6.0 |

| 1995-2005 | 92.4 | 6.8 |

| 2000-2005 | 46.3 | 7.9 |

| 1995-2018 | -6.7 | NA |

| 2000-2018 | -29.1 | NA |

| 2005-2018 | -51.5 | NA |

NA: Not Applicable

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

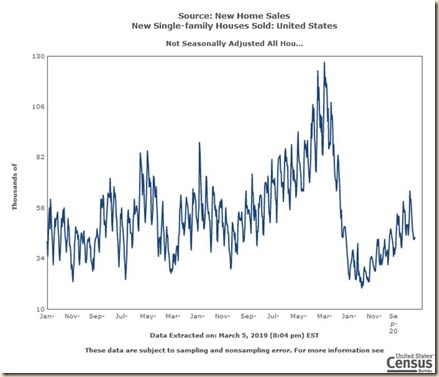

Chart IIB-2 of the US Bureau of the Census provides the entire monthly sample of new houses sold in the US between Jan 1963 and Dec 2018 without seasonal adjustment. The series is almost stationary until the 1990s. There is sharp upward trend from the early 1990s to 2005-2006 after which new single-family houses sold collapse to levels below those in the beginning of the series.

Chart IIB-2, US, New Single-family Houses Sold, NSA, 1963-2018

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

The available historical annual data of median and average prices of new houses sold in the US between 1963 and 2018 is in Table IIB-6. On a yearly basis, median and average prices reached a peak in 2007 and then fell substantially. There is recovery in 2012-2017.

Table IIB-6, US, Median and Average Prices of New Houses Sold, Annual Data

| Period | Median | Average |

| 1963 | $18,000 | $19,300 |

| 1964 | $18,900 | $20,500 |

| 1965 | $20,000 | $21,500 |

| 1966 | $21,400 | $23,300 |

| 1967 | $22,700 | $24,600 |

| 1968 | $24,700 | $26,600 |

| 1969 | $25,600 | $27,900 |

| 1970 | $23,400 | $26,600 |

| 1971 | $25,200 | $28,300 |

| 1972 | $27,600 | $30,500 |

| 1973 | $32,500 | $35,500 |

| 1974 | $35,900 | $38,900 |

| 1975 | $39,300 | $42,600 |

| 1976 | $44,200 | $48,000 |

| 1977 | $48,800 | $54,200 |

| 1978 | $55,700 | $62,500 |

| 1979 | $62,900 | $71,800 |

| 1980 | $64,600 | $76,400 |

| 1981 | $68,900 | $83,000 |

| 1982 | $69,300 | $83,900 |

| 1983 | $75,300 | $89,800 |

| 1984 | $79,900 | $97,600 |

| 1985 | $84,300 | $100,800 |

| 1986 | $92,000 | $111,900 |

| 1987 | $104,500 | $127,200 |

| 1988 | $112,500 | $138,300 |

| 1989 | $120,000 | $148,800 |

| 1990 | $122,900 | $149,800 |

| 1991 | $120,000 | $147,200 |

| 1992 | $121,500 | $144,100 |

| 1993 | $126,500 | $147,700 |

| 1994 | $130,000 | $154,500 |

| 1995 | $133,900 | $158,700 |

| 1996 | $140,000 | $166,400 |

| 1997 | $146,000 | $176,200 |

| 1998 | $152,500 | $181,900 |

| 1999 | $161,000 | $195,600 |

| 2000 | $169,000 | $207,000 |

| 2001 | $175,200 | $213,200 |

| 2002 | $187,600 | $228,700 |

| 2003 | $195,000 | $246,300 |

| 2004 | $221,000 | $274,500 |

| 2005 | $240,900 | $297,000 |

| 2006 | $246,500 | $305,900 |

| 2007 | $247,900 | $313,600 |

| 2008 | $232,100 | $292,600 |

| 2009 | $216,700 | $270,900 |

| 2010 | $221,800 | $272,900 |

| 2011 | $227,200 | $267,900 |

| 2012 | $245,200 | $292,200 |

| 2013 | $268,900 | $324,500 |

| 2014 | $288,500 | $347,700 |

| 2015 | $294,200 | $352,700 |

| 2016 | $307,800 | $360,900 |

| 2017 | $323,100 | $384,900 |

| 2018 | $324,800 | $383,500 |

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

Prices rose sharply between 2000 and 2005 as shown in Table IIB-7. In fact, prices in 2018 are higher than in 2000. Between 2006 and 2018, median prices of new houses sold increased 31.8 percent and average prices increased 25.4 percent. Between 2017 and 2018, median prices increased 0.5 percent and average prices decreased 0.4 percent.

Table IIB-7, US, Percentage Change of New Houses Median and Average Prices, NSA, ∆%

| Median New | Average New Home Sales Prices ∆% | |

| ∆% 2000 to 2003 | 15.4 | 19.0 |

| ∆% 2000 to 2005 | 42.5 | 43.5 |

| ∆% 2000 to 2018 | 92.2 | 85.3 |

| ∆% 2005 to 2018 | 34.8 | 29.1 |

| ∆% 2000 to 2006 | 45.9 | 47.8 |

| ∆% 2006 to 2018 | 31.8 | 25.4 |

| ∆% 2009 to 2018 | 49.9 | 41.6 |

| ∆% 2010 to 2018 | 46.4 | 40.5 |

| ∆% 2011 to 2018 | 43.0 | 43.2 |

| ∆% 2012 to 2018 | 32.5 | 31.2 |

| ∆% 2013 to 2018 | 20.8 | 18.2 |

| ∆% 2014 to 2018 | 12.6 | 10.3 |

| ∆% 2015 to 2018 | 10.4 | 8.7 |

| ∆% 2016 to 2018 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| ∆% 2017 to 2018 | 0.5 | -0.4 |

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

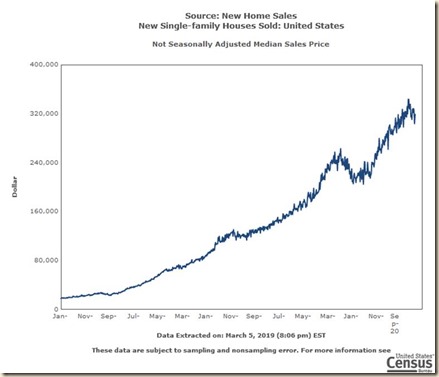

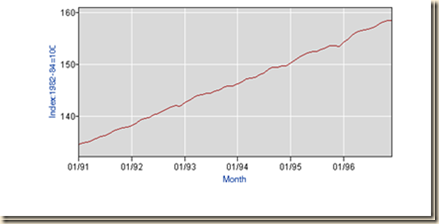

Chart IIB-3 of the US Census Bureau provides the entire series of new single-family sales median prices from Jan 1963 to Dec 2018. There is long-term sharp upward trend with few declines until the current collapse. Median prices increased sharply during the Great Inflation of the 1960s and 1970s and paused during the savings and loans crisis of the late 1980s and the recession of 1991. Housing subsidies throughout the 1990s caused sharp upward trend of median new house prices that accelerated after the fed funds rate of 1 percent from 2003 to 2004. There was sharp reduction of prices after 2006 with recovery recently above earlier prices.

Chart IIB-3, US, Median Sales Price of New Single-family Houses Sold, US Dollars, NSA, 1963-2018

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

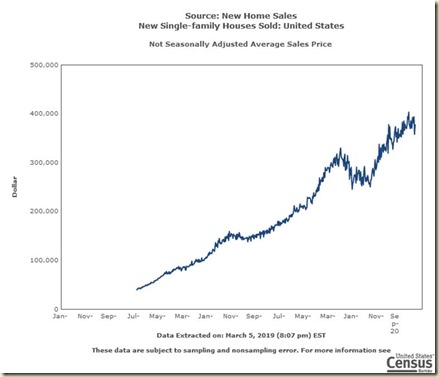

Chart IIB-4 of the US Census Bureau provides average prices of new houses sold from the mid-1970s to Dec 2018. There is similar behavior as with median prices of new houses sold in Chart IIB-3. The only stress occurred in price pauses during the savings and loans crisis of the late 1980s and the collapse after 2006 with recent recovery.

Chart IIB-4, US, Average Sales Price of New Single-family Houses Sold, US Dollars, NSA, 1975-2018

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/

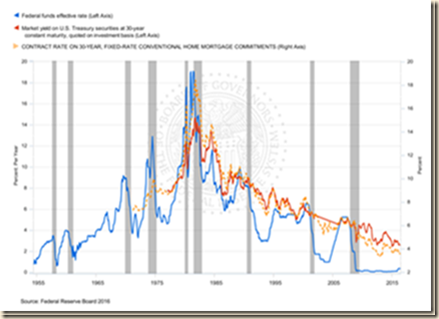

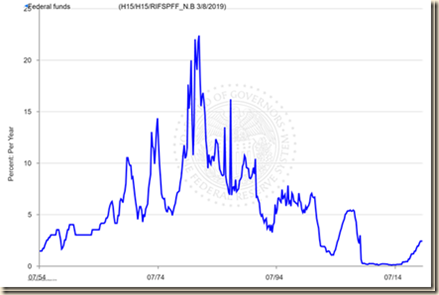

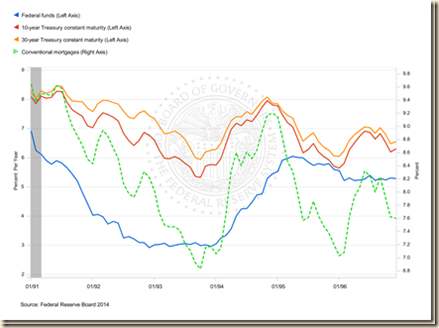

Chart IIB-5 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate for the 30-year conventional mortgage, the yield of the 30-year Treasury bond and the rate of the overnight federal funds rate, monthly, from 1954 to 2016. All rates decline throughout the period from the Great Inflation of the 1970s through the following Great Moderation and until currently. In Apr 1971, the fed funds rate was 4.15 percent and the conventional mortgage rate 7.31 percent. In November 2012, the fed funds rate was 0.16 percent, the yield of the 30-year Treasury 2.80 percent and the conventional mortgage rate 3.35. The final segment shows an increase in the yield of the 30-year Treasury to 3.61 percent in July 2013 with the fed funds rate at 0.09 percent and the conventional mortgage at 4.37 percent. The final data point shows marginal decrease of the conventional mortgage rate to 3.60 percent in May 2016 with the yield of the 30-year Treasury bond at 2.63 percent and overnight rate on fed funds at 0.37 percent. The recent increase in interest rates if sustained could affect the US real estate market. Shayndi Raice and Nick Timiraos, writing on “Banks cut as mortgage boom ends,” on Jan 9, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303754404579310940019239208), analyze the drop in mortgage applications to a 13-year low, as measured by the Mortgage Bankers Association. Nick Timiraos, writing on “Demand for home loans plunges,” on Apr 24, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304788404579522051733228402?mg=reno64-wsj), analyzes data in Inside Mortgage Finance that mortgage lending of $235 billion in IQ2014 is 58 percent lower than a year earlier and 23 percent below IVQ2013. Mortgage lending collapsed to the lowest level in 14 years. In testimony before the Committee on the Budget of the US Senate on May 8, 2004, Chair Yellen provides analysis of the current economic situation and outlook (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20140507a.htm): “One cautionary note, though, is that readings on housing activity--a sector that has been recovering since 2011--have remained disappointing so far this year and will bear watching.”

Chart IIB-5, US, Thirty-year Conventional Mortgage, Thirty-year Treasury Bond and Overnight Federal Funds Rate, Monthly, 1954-2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H15/default.htm

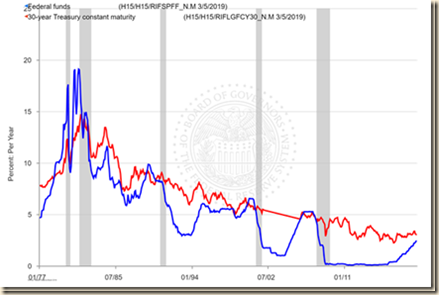

Chart IIB-5A of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the yield of the 30-year Treasury bond and the rate of the overnight federal funds rate, monthly, from 2001 to 2019. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System discontinued the conventional mortgage rate in its data bank. The final data point is 2.40 percent for the fed funds rate in Feb 2019 and 3.02 percent for the thirty-year Treasury bond. The conventional mortgage rate stood at 4.37 percent in Feb 2019.

Chart IIB-5A, US, Thirty-year Treasury Bond and Overnight Federal Funds Rate, Monthly, 1977-2019

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H15/default.htm

Table IIB-8, US, Fed Funds Rate, Thirty Year Treasury Bond and Conventional Mortgage Rate, Monthly, Percent per Year, Dec 2012 to Mar 2018

| Fed Funds Rate | Yield of Thirty Year Constant Maturity | Conventional Mortgage Rate | |

| 2012-12 | 0.16 | 2.88 | 3.35 |

| 2013-01 | 0.14 | 3.08 | 3.41 |

| 2013-02 | 0.15 | 3.17 | 3.53 |

| 2013-03 | 0.14 | 3.16 | 3.57 |

| 2013-04 | 0.15 | 2.93 | 3.45 |

| 2013-05 | 0.11 | 3.11 | 3.54 |

| 2013-06 | 0.09 | 3.40 | 4.07 |

| 2013-07 | 0.09 | 3.61 | 4.37 |

| 2013-08 | 0.08 | 3.76 | 4.46 |

| 2013-09 | 0.08 | 3.79 | 4.49 |

| 2013-10 | 0.09 | 3.68 | 4.19 |

| 2013-11 | 0.08 | 3.80 | 4.26 |

| 2013-12 | 0.09 | 3.89 | 4.46 |

| 2014-01 | 0.07 | 3.77 | 4.43 |

| 2014-02 | 0.07 | 3.66 | 4.30 |

| 2014-03 | 0.08 | 3.62 | 4.34 |

| 2014-04 | 0.09 | 3.52 | 4.34 |

| 2014-05 | 0.09 | 3.39 | 4.19 |

| 2014-06 | 0.10 | 3.42 | 4.16 |

| 2014-07 | 0.09 | 3.33 | 4.13 |

| 2014-08 | 0.09 | 3.2 | 4.12 |

| 2014-09 | 0.09 | 3.26 | 4.16 |

| 2014-10 | 0.09 | 3.04 | 4.04 |

| 2014-11 | 0.09 | 3.04 | 4.00 |

| 2014-12 | 0.12 | 2.83 | 3.86 |

| 2015-01 | 0.11 | 2.46 | 3.67 |

| 2015-02 | 0.11 | 2.57 | 3.71 |

| 2015-03 | 0.11 | 2.63 | 3.77 |

| 2015-04 | 0.12 | 2.59 | 3.67 |

| 2015-05 | 0.12 | 2.96 | 3.84 |

| 2015-06 | 0.13 | 3.11 | 3.98 |

| 2015-07 | 0.13 | 3.07 | 4.05 |

| 2015-08 | 0.14 | 2.86 | 3.91 |

| 2015-09 | 0.14 | 2.95 | 3.89 |

| 2015-10 | 0.12 | 2.89 | 3.80 |

| 2015-11 | 0.12 | 3.03 | 3.94 |

| 2015-12 | 0.24 | 2.97 | 3.96 |

| 2016-01 | 0.34 | 2.86 | 3.87 |

| 2016-02 | 0.38 | 2.62 | 3.66 |

| 2016-03 | 0.36 | 2.68 | 3.69 |

| 2016-04 | 0.37 | 2.62 | 3.61 |

| 2016-05 | 0.37 | 2.63 | 3.60 |

| 2016-06 | 0.38 | 2.45 | 3.57 |

| 2016-07 | 0.39 | 2.23 | 3.44 |

| 2016-08 | 0.40 | 2.26 | 3.44 |

| 2016-09 | 0.40 | 2.35 | 3.46 |

| 2016-10 | 0.40 | 2.50 | 3.47 |

| 2016-11 | 0.41 | 2.86 | 3.77 |

| 2016-12 | 0.54 | 3.11 | 4.20 |

| 2017-01 | 0.65 | 3.02 | 4.15 |

| 2017-02 | 0.66 | 3.03 | 4.17 |

| 2017-03 | 0.79 | 3.08 | 4.20 |

| 2017-04 | 0.90 | 2.94 | 4.05 |

| 2017-05 | 0.91 | 2.96 | 4.01 |

| 2017-06 | 1.04 | 2.80 | 3.90 |

| 2017-07 | 1.15 | 2.88 | 3.97 |

| 2017-08 | 1.16 | 2.80 | 3.88 |

| 2017-09 | 1.15 | 2.78 | 3.81 |

| 2017-10 | 1.15 | 2.88 | 3.90 |

| 2017-11 | 1.16 | 2.80 | 3.92 |

| 2017-12 | 1.30 | 2.77 | 3.95 |

| 2018-01 | 1.41 | 2.88 | 4.03 |

| 2018-02 | 1.42 | 3.13 | 4.33 |

| 2018-03 | 1.51 | 3.09 | 4.44 |

| 2018-04 | 1.69 | 3.07 | 4.47 |

| 2018-05 | 1.70 | 3.13 | 4.59 |

| 2018-06 | 1.82 | 3.05 | 4.57 |

| 2018-07 | 1.91 | 3.01 | 4.53 |

| 2018-08 | 1.91 | 3.04 | 4.55 |

| 2018-09 | 1.95 | 3.15 | 4.63 |

| 2018-10 | 2.19 | 3.34 | 4.83 |

| 2018-11 | 2.20 | 3.36 | 4.87 |

| 2018-12 | 2.27 | 3.10 | 4.64 |

| 2019-01 | 2.40 | 3.04 | 4.46 |

| 2019-02 | 2.40 | 3.02 | 4.37 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H15/default.htm

http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/pmms30.htm

IIB2 United States House Prices. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which regulates Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, provides the FHFA House Price Index (HPI) that “is calculated using home sales price information from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac-acquired mortgages” (http://fhfa.gov/webfiles/24216/q22012hpi.pdf 1). The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which regulates Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, provides the FHFA House Price Index (HPI) that “is calculated using home sales price information from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac-acquired mortgages” (http://fhfa.gov/webfiles/24216/q22012hpi.pdf 1). Table IIA2-1 provides the FHFA HPI for purchases only, which shows behavior similar to that of the Case-Shiller index but with lower magnitudes. House prices catapulted from 2000 to 2003, 2005 and 2006. From IVQ2000 to IVQ2006, the index for the US as a whole rose 55.0 percent, with 62.1 percent for New England, 72.0 percent for Middle Atlantic, 71.2 percent for South Atlantic but only by 33.1 percent for East South Central. Prices fell relative to 2014 for the US and all regions from 2006 with exception of increase of 2.6 percent for East South Central. Prices for the US increased 4.9 percent in IVQ2014 relative to IVQ2013 and 12.9 percent from IVQ2012 to IVQ2014. From IVQ2000 to IVQ2014, prices rose for the US and the four regions in Table IIA2-1.

Table IIA2-1, US, FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only NSA ∆%

| United States | New England | Middle Atlantic | South Atlantic | East South Central | |

| IVQ2000 | 24.0 | 40.6 | 35.8 | 25.9 | 11.0 |

| IVQ2000 | 50.5 | 65.0 | 67.6 | 62.9 | 25.4 |

| IVQ2000 to | 55.0 | 62.1 | 72.0 | 71.2 | 33.1 |

| IVQ2005 to | -1.5 | -8.7 | -2.3 | -7.4 | 8.9 |

| IVQ2006 | -4.4 | -7.1 | -4.8 | -11.9 | 2.6 |

| IVQ2007 to | -1.9 | -5.1 | -5.0 | -8.6 | 0.7 |

| IVQ2011 to | 18.9 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 19.9 | 11.8 |

| IVQ2012 to | 12.9 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 13.8 | 8.6 |

| IVQ2013 to IVQ2014 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| IVQ2000 to | 48.3 144.27 | 50.6 138.40 | 63.7 127.30 | 50.9 140.28 | 36.6 146.07 |

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency

http://www.fhfa.gov/KeyTopics/Pages/House-Price-Index.aspx

Data of the FHFA HPI for the remaining US regions are in Table IIA2-2. Behavior is not very different from that in Table IIA2-1 with the exception of East North Central. House prices in the Pacific region doubled between 2000 and 2006. Although prices of houses declined sharply from 2005 and 2006 to 2014 with exception of West South Central and West North Central, there was still appreciation relative to 2000.

Table IIA2-2, US, FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only NSA ∆%

| West South Central | West North Central | East North Central | Mountain | Pacific | |

| IVQ2000 | 11.1 | 18.3 | 14.7 | 18.9 | 44.6 |

| IVQ2000 | 23.9 | 31.0 | 23.8 | 58.0 | 107.7 |

| IVQ2000 to IVQ2006 | 31.6 | 33.7 | 23.7 | 68.6 | 108.7 |

| IVQ2005 to | 26.6 | 4.7 | -5.4 | -2.6 | -14.7 |

| IVQ2006 | 19.1 | 2.6 | -5.4 | -8.7 | -15.1 |

| IVQ2007 to | 15.2 | 3.2 | -2.1 | -5.6 | -6.0 |

| IVQ2011 to | 18.1 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 32.9 | 37.6 |

| IVQ2012 to | 12.1 | 8.9 | 11.1 | 17.9 | 24.4 |

| IVQ2013 to IVQ2014 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 7.3 |

| IVQ2000 to IVQ2014 | 56.8 145.53 | 37.1 158.59 | 17.1 155.13 | 53.9 172.46 | 77.1 132.21 |

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency

http://www.fhfa.gov/KeyTopics/Pages/House-Price-Index.aspx

Monthly and 12-month percentage changes of the FHFA House Price Index are in Table IIA2-3. Percentage monthly increases of the FHFA index were positive from Apr to Jul 2011 with exception of declines in May and Aug 2011 while 12-month percentage changes improved steadily from around minus 6.0 percent in Mar to May 2011 to minus 4.5 percent in Jun 2011. The FHFA house price index fell 0.6 percent in Oct 2011 and fell 3.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Oct 2011. There was significant recovery in Nov 2011 with increase in the house price index of 0.5 percent and reduction of the 12-month rate of decline to 2.4 percent. The house price index rose 0.3 percent in Dec 2011 and the 12-month percentage change improved to minus 1.4 percent. There was further improvement with revised change of minus 0.3 percent in Jan 2012 and decline of the 12-month percentage change to minus 1.3 percent. The index improved to positive change of 0.2 percent in Feb 2012 and decrease of 0.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb 2012. There was strong improvement in Mar 2012 with gain in prices of 0.8 percent and 1.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index of FHFA increased 0.6 percent in Apr 2012 and 2.3 percent in 12 months and improvement continued with increase of 0.7 percent in May 2012 and 3.2 percent in the 12 months ending in May 2012. Improvement consolidated with increase of 0.4 percent in Jun 2012 and 3.3 percent in 12 months. In Jul 2012, the house price index increased 0.2 percent and 3.3 percent in 12 months. Strong increase of 0.6 percent in Aug 2012 pulled the 12-month change to 4.1 percent. There was another increase of 0.5 percent in Oct 2012 and 4.9 percent in 12 months followed by increase of 0.5 percent in Nov 2012 and 4.9 percent in 12 months. The FHFA house price index increased 0.8 percent in Jan 2013 and 6.3 percent in 12 months. Improvement continued with increase of 1.0 percent in Apr 2013 and 7.1 percent in 12 months. In May 2013, the house price indexed increased 0.6 percent and 7.2 percent in 12 months. The FHFA house price index increased 0.6 percent in Jun 2013 and 7.5 percent in 12 months. In Jul 2013, the FHFA house price index increased 0.6 percent and 7.8 percent in 12 months. Improvement continued with increase of 0.3 percent in Aug 2013 and 7.5 percent in 12 months. In Sep 2013, the house price index increased 0.5 percent and 7.6 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.3 percent in Oct 2013 and 7.3 percent in 12 months. In Nov 2013, the house price index increased 0.1 percent and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index rose 0.5 percent in Dec 2013 and 6.9 percent in 12 months. Improvement continued with increase of 0.5 percent in Jan 2014 and 6.6 percent in 12 months. In Feb 2014, the house price index increased 0.5 percent and 6.5 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.3 percent in Mar 2014 and 5.9 percent in 12 months. In Apr 2014, the house price index increased 0.3 percent and increased 5.5 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.2 percent in May 2014 and 4.8 percent in 12 months. In Jun 2014, the house price index increased 0.5 percent and 4.7 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Jul 2014 and 4.5 percent in 12 months. In Sep 2014, the house price index increased 0.1 percent and increased 4.2 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.6 percent in Oct 2014 and 4.5 percent in 12 months. In Nov 2014, the house price index increased 0.4 percent and 4.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.7 percent in Dec 2014 and increased 5.2 percent in 12 months. In Mar 2015, the house price index increased 0.3 percent and increased 5.2 percent in 12 months. In Apr 2015, the house price index increased 0.3 percent and 5.2 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.6 percent in May 2015 and 5.5 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.5 percent in Jun 2015 and 5.4 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Jul 2015 and increased 5.4 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.2 percent in Aug 2015 and increased 5.1 percent in 12 months. In Sep 2015, the house price index increased 0.7 percent and increased 5.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.5 percent in Oct 2015 and increased 5.6 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.6 percent in Nov 2015 and increased 5.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Dec 2015 and increased 5.6 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.6 percent in Jan 2016 and increased 6.1 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.2 percent in Feb 2016 and increased 5.6 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.7 percent in Mar 2016 and increased 6.0 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Apr 2016 and increased 6.0 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.4 percent in May 2016 and increased 5.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.5 percent in Jun 2016 and increased 5.7 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.6 percent in Jul 2016 and increased 5.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.5 percent in Aug 2016 and increased 6.2 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.7 percent in Sep 2016 and increased 6.3 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.5 percent in Oct 2016 and increased 6.3 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.6 percent in Nov 2016 and increased 6.4 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Dec 2016 and increased 6.4 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.2 percent in Jan 2017 and increased 5.9 percent in 12 months. In Feb 2017, the house price index increased 0.9 percent and increased 6.7 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.5 percent in Mar 2017 and increased 6.5 percent in 12 months. In Apr 2017, the house price index increased 0.7 percent and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.4 percent in May 2017 and increased 6.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.3 percent in Jun 2017 and increased 6.5 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.6 percent in Jul 2017 and increased 6.6 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.8 percent in Aug 2017 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.5 percent in Sep 2017 and increased 6.7 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.8 percent in Oct 2017 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.5 percent in Nov 2017 and increased 6.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.5 percent in Dec 2017 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.8 percent in Jan 2018 and increased 7.6 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 1.0 percent in Feb 2018 and increased 7.8 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.1 percent in Mar 2018 and increased 7.3 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.3 percent in Apr 2018 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in May 2018 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months ending in May 2018. House prices increased 0.4 percent in Jun 2016 and increased 6.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in July 2018 and increased 6.8 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.5 percent in Aug 2018 and increased 6.5 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.3 percent in Sep 2018 and increased 6.3 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.4 percent in Oct 2018 and increased 5.9 percent in 12 months. The house price index increased 0.4 percent in Nov 2018 and increased 5.9 percent in 12 months. House prices increased 0.3 percent in Dec 2018 and increased 5.6 percent in 12 months.

Table IIA2-3, US, FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only SA. Month and NSA 12-Month ∆%

| Month ∆% SA | 12 Month ∆% NSA | |||

| 12/1/2018 | 0.3 | 5.6 | ||

| 11/1/2018 | 0.4 | 5.9 | ||

| 10/1/2018 | 0.4 | 5.9 | ||

| 9/1/2018 | 0.3 | 6.3 | ||

| 8/1/2018 | 0.5 | 6.5 | ||

| 7/1/2018 | 0.4 | 6.8 | ||

| 6/1/2018 | 0.4 | 6.9 | ||

| 5/1/2018 | 0.4 | 6.9 | ||

| 4/1/2018 | 0.3 | 6.9 | ||

| 3/1/2018 | 0.1 | 7.3 | ||

| 2/1/2018 | 1.0 | 7.8 | ||

| 1/1/2018 | 0.8 | 7.6 | ||

| 12/1/2017 | 0.5 | 6.9 | ||

| 11/1/2017 | 0.5 | 6.8 | ||

| 10/1/2017 | 0.8 | 6.9 | ||

| 9/1/2017 | 0.5 | 6.7 | ||

| 8/1/2017 | 0.8 | 6.9 | ||

| 7/1/2017 | 0.6 | 6.6 | ||

| 6/1/2017 | 0.3 | 6.5 | ||

| 5/1/2017 | 0.4 | 6.8 | ||

| 4/1/2017 | 0.7 | 6.9 | ||

| 3/1/2017 | 0.5 | 6.5 | ||

| 2/1/2017 | 0.9 | 6.7 | ||

| 1/1/2017 | 0.2 | 5.9 | ||

| 12/1/2016 | 0.4 | 6.4 | ||

| 11/1/2016 | 0.6 | 6.4 | ||

| 10/1/2016 | 0.5 | 6.3 | ||

| 9/1/2016 | 0.7 | 6.3 | ||

| 8/1/2016 | 0.5 | 6.2 | ||

| 7/1/2016 | 0.6 | 5.9 | ||

| 6/1/2016 | 0.5 | 5.7 | ||

| 5/1/2016 | 0.4 | 5.8 | ||

| 4/1/2016 | 0.4 | 6.0 | ||

| 3/1/2016 | 0.7 | 6.0 | ||

| 2/1/2016 | 0.2 | 5.6 | ||

| 1/1/2016 | 0.6 | 6.1 | ||

| 12/1/2015 | 0.4 | 5.6 | ||

| 11/1/2015 | 0.6 | 5.8 | ||

| 10/1/2015 | 0.5 | 5.6 | ||

| 9/1/2015 | 0.7 | 5.8 | ||

| 8/1/2015 | 0.2 | 5.1 | ||

| 7/1/2015 | 0.4 | 5.4 | ||

| 6/1/2015 | 0.5 | 5.4 | ||

| 5/1/2015 | 0.6 | 5.5 | ||

| 4/1/2015 | 0.3 | 5.2 | ||

| 3/1/2015 | 0.3 | 5.2 | ||

| 2/1/2015 | 0.8 | 5.1 | ||

| 1/1/2015 | 0.1 | 4.8 | ||

| 12/1/2014 | 0.7 | 5.2 | ||

| 11/1/2014 | 0.4 | 4.9 | ||

| 10/1/2014 | 0.6 | 4.5 | ||

| 9/1/2014 | 0.1 | 4.2 | ||

| 8/1/2014 | 0.5 | 4.6 | ||

| 7/1/2014 | 0.4 | 4.5 | ||

| 6/1/2014 | 0.5 | 4.7 | ||

| 5/1/2014 | 0.2 | 4.8 | ||

| 4/1/2014 | 0.3 | 5.5 | ||

| 3/1/2014 | 0.3 | 5.9 | ||

| 2/1/2014 | 0.5 | 6.5 | ||

| 1/1/2014 | 0.5 | 6.6 | ||

| 12/1/2013 | 0.5 | 6.9 | ||

| 11/1/2013 | 0.1 | 6.9 | ||

| 10/1/2013 | 0.3 | 7.3 | ||

| 9/1/2013 | 0.5 | 7.6 | ||

| 8/1/2013 | 0.3 | 7.5 | ||

| 7/1/2013 | 0.6 | 7.8 | ||

| 6/1/2013 | 0.6 | 7.5 | ||

| 5/1/2013 | 0.8 | 7.2 | ||

| 4/1/2013 | 0.6 | 7.1 | ||

| 3/1/2013 | 1.0 | 7.1 | ||

| 2/1/2013 | 0.6 | 6.8 | ||

| 1/1/2013 | 0.8 | 6.3 | ||

| 12/1/2012 | 0.5 | 5.2 | ||

| 11/1/2012 | 0.5 | 4.9 | ||

| 10/1/2012 | 0.5 | 4.9 | ||

| 9/1/2012 | 0.4 | 3.8 | ||

| 8/1/2012 | 0.6 | 4.1 | ||

| 7/1/2012 | 0.2 | 3.3 | ||

| 6/1/2012 | 0.4 | 3.3 | ||

| 5/1/2012 | 0.7 | 3.2 | ||

| 4/1/2012 | 0.6 | 2.3 | ||

| 3/1/2012 | 0.8 | 1.9 | ||

| 2/1/2012 | 0.2 | -0.1 | ||

| 1/1/2012 | -0.3 | -1.3 | ||

| 12/1/2011 | 0.3 | -1.4 | ||

| 11/1/2011 | 0.5 | -2.4 | ||

| 10/1/2011 | -0.6 | -3.3 | ||

| 9/1/2011 | 0.6 | -2.5 | ||

| 8/1/2011 | -0.3 | -4.0 | ||

| 7/1/2011 | 0.3 | -3.6 | ||

| 6/1/2011 | 0.4 | -4.5 | ||

| 5/1/2011 | -0.2 | -5.9 | ||

| 4/1/2011 | 0.2 | -5.8 | ||

| 3/1/2011 | -1.0 | -5.9 | ||

| 2/1/2011 | -1.0 | -5.2 | ||

| 1/1/2011 | -0.4 | -4.5 | ||

| 12/1/2010 | -0.8 | -3.9 | ||

| 12/1/2009 | -1.0 | -2.0 | ||

| 12/1/2008 | -0.3 | -10.4 | ||

| 12/1/2007 | -0.5 | -3.4 | ||

| 12/1/2006 | 0.1 | 2.4 | ||

| 12/1/2005 | 0.6 | 9.8 | ||

| 12/1/2004 | 0.9 | 10.2 | ||

| 12/1/2003 | 0.9 | 8.0 | ||

| 12/1/2002 | 0.7 | 7.8 | ||

| 12/1/2001 | 0.6 | 6.7 | ||

| 12/1/2000 | 0.6 | 7.1 | ||

| 12/1/1999 | 0.5 | 6.1 | ||

| 12/1/1998 | 0.4 | 5.9 | ||

| 12/1/1997 | 0.3 | 3.4 | ||

| 12/1/1996 | 0.3 | 2.7 | ||

| 12/1/1995 | 0.4 | 3.0 | ||

| 12/1/1994 | 0.0 | 2.5 | ||

| 12/1/1993 | 0.5 | 3.1 | ||

| 12/1/1992 | -0.1 | 2.4 |

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency

The bottom part of Table IIA2-3 provides 12-month percentage changes of the FHFA house price index since 1992 when data become available for 1991. Table IIA2-4 provides percentage changes and average rates of percent change per year for various periods. Between 1992 and 2018, the FHFA house price index increased 157.9 percent at the yearly average rate of 3.7 percent. In the period 1992-2000, the FHFA house price index increased 39.2 percent at the average yearly rate of 4.2 percent. The average yearly rate of price increase accelerated to 7.5 percent in the period 2000-2003, 8.5 percent in 2000-2005 and 7.4 percent in 2000-2006. At the margin, the average rate jumped to 10.0 percent in 2003-2005 and 7.4 percent in 2003-2006. House prices measured by the FHFA house price index increased 20.5 percent at the average yearly rate of 1.6 percent between 2006 and 2018 and 23.3 percent between 2005 and 2018 at the average yearly rate of 1.6 percent.

| Dec | ∆% | Average ∆% per Year |

| 1992-2018 | 157.9 | 3.7 |

| 1992-2000 | 39.2 | 4.2 |

| 2000-2003 | 24.2 | 7.5 |

| 2000-2005 | 50.2 | 8.5 |

| 2003-2005 | 21.0 | 10.0 |

| 2005-2018 | 23.3 | 1.6 |

| 2000-2006 | 53.8 | 7.4 |

| 2003-2006 | 23.8 | 7.4 |

| 2006-2018 | 20.5 | 1.6 |

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency

The explanation of the sharp contraction of household wealth can probably be found in the origins of the financial crisis and global recession. Let V(T) represent the value of the firm’s equity at time T and B stand for the promised debt of the firm to bondholders and assume that corporate management, elected by equity owners, is acting on the interests of equity owners. Robert C. Merton (1974, 453) states:

“On the maturity date T, the firm must either pay the promised payment of B to the debtholders or else the current equity will be valueless. Clearly, if at time T, V(T) > B, the firm should pay the bondholders because the value of equity will be V(T) – B > 0 whereas if they do not, the value of equity would be zero. If V(T) ≤ B, then the firm will not make the payment and default the firm to the bondholders because otherwise the equity holders would have to pay in additional money and the (formal) value of equity prior to such payments would be (V(T)- B) < 0.”

Pelaez and Pelaez (The Global Recession Risk (2007), 208-9) apply this analysis to the US housing market in 2005-2006 concluding:

“The house market [in 2006] is probably operating with low historical levels of individual equity. There is an application of structural models [Duffie and Singleton 2003] to the individual decisions on whether or not to continue paying a mortgage. The costs of sale would include realtor and legal fees. There could be a point where the expected net sale value of the real estate may be just lower than the value of the mortgage. At that point, there would be an incentive to default. The default vulnerability of securitization is unknown.”

There are multiple important determinants of the interest rate: “aggregate wealth, the distribution of wealth among investors, expected rate of return on physical investment, taxes, government policy and inflation” (Ingersoll 1987, 405). Aggregate wealth is a major driver of interest rates (Ibid, 406). Unconventional monetary policy, with zero fed funds rates and flattening of long-term yields by quantitative easing, causes uncontrollable effects on risk taking that can have profound undesirable effects on financial stability. Excessively aggressive and exotic monetary policy is the main culprit and not the inadequacy of financial management and risk controls.

The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Ibid). According to a subsequent restatement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption decisions is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r →0, W grows without bound, W→∞.

Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment but the exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at close to zero interest rates, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV).

The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper to purchase default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and worked with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity because of the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions because the put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4).

There are significant elements of the theory of bank financial fragility of Diamond and Dybvig (1983) and Diamond and Rajan (2000, 2001a, 2001b) that help to explain the financial fragility of banks during the credit/dollar crisis (see also Diamond 2007). The theory of Diamond and Dybvig (1983) as exposed by Diamond (2007) is that banks funding with demand deposits have a mismatch of liquidity (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 58-66). A run occurs when too many depositors attempt to withdraw cash at the same time. All that is needed is an expectation of failure of the bank. Three important functions of banks are providing evaluation, monitoring and liquidity transformation. Banks invest in human capital to evaluate projects of borrowers in deciding if they merit credit. The evaluation function reduces adverse selection or financing projects with low present value. Banks also provide important monitoring services of following the implementation of projects, avoiding moral hazard that funds be used for, say, real estate speculation instead of the original project of factory construction. The transformation function of banks involves both assets and liabilities of bank balance sheets. Banks convert an illiquid asset or loan for a project with cash flows in the distant future into a liquid liability in the form of demand deposits that can be withdrawn immediately.

In the theory of banking of Diamond and Rajan (2000, 2001a, 2001b), the bank creates liquidity by tying human assets to capital. The collection skills of the relationship banker convert an illiquid project of an entrepreneur into liquid demand deposits that are immediately available for withdrawal. The deposit/capital structure is fragile because of the threat of bank runs. In these days of online banking, the run on Washington Mutual was through withdrawals online. A bank run can be triggered by the decline of the value of bank assets below the value of demand deposits.

Pelaez and Pelaez (Regulation of Banks and Finance 2009b, 60, 64-5) find immediate application of the theories of banking of Diamond, Dybvig and Rajan to the credit/dollar crisis after 2007. It is a credit crisis because the main issue was the deterioration of the credit portfolios of securitized banks as a result of default of subprime mortgages. It is a dollar crisis because of the weakening dollar resulting from relatively low interest rate policies of the US. It caused systemic effects that converted into a global recession not only because of the huge weight of the US economy in the world economy but also because the credit crisis transferred to the UK and Europe. Management skills or human capital of banks are illustrated by the financial engineering of complex products. The increasing importance of human relative to inanimate capital (Rajan and Zingales 2000) is revolutionizing the theory of the firm (Zingales 2000) and corporate governance (Rajan and Zingales 2001). Finance is one of the most important examples of this transformation. Profits were derived from the charter in the original banking institution. Pricing and structuring financial instruments was revolutionized with option pricing formulas developed by Black and Scholes (1973) and Merton (1973, 1974, 1998) that permitted the development of complex products with fair pricing. The successful financial company must attract and retain finance professionals who have invested in human capital, which is a sunk cost to them and not of the institution where they work.

The complex financial products created for securitized banking with high investments in human capital are based on houses, which are as illiquid as the projects of entrepreneurs in the theory of banking. The liquidity fragility of the securitized bank is equivalent to that of the commercial bank in the theory of banking (Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 65). Banks created off-balance sheet structured investment vehicles (SIV) that issued commercial paper receiving AAA rating because of letters of liquidity guarantee by the banks. The commercial paper was converted into liquidity by its use as collateral in SRPs at the lowest rates and minimal haircuts because of the AAA rating of the guarantor bank. In the theory of banking, default can be triggered when the value of assets is perceived as lower than the value of the deposits. Commercial paper issued by SIVs, securitized mortgages and derivatives all obtained SRP liquidity on the basis of illiquid home mortgage loans at the bottom of the pyramid. The run on the securitized bank had a clear origin (Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 65):

“The increasing default of mortgages resulted in an increase in counterparty risk. Banks were hit by the liquidity demands of their counterparties. The liquidity shock extended to many segments of the financial markets—interbank loans, asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), high-yield bonds and many others—when counterparties preferred lower returns of highly liquid safe havens, such as Treasury securities, than the risk of having to sell the collateral in SRPs at deep discounts or holding an illiquid asset. The price of an illiquid asset is near zero.”

Gorton and Metrick (2010H, 507) provide a revealing quote to the work in 1908 of Edwin R. A. Seligman, professor of political economy at Columbia University, founding member of the American Economic Association and one of its presidents and successful advocate of progressive income taxation. The intention of the quote is to bring forth the important argument that financial crises are explained in terms of “confidence” but as Professor Seligman states in reference to historical banking crises in the US, the important task is to explain what caused the lack of confidence. It is instructive to repeat the more extended quote of Seligman (1908, xi) on the explanations of banking crises:

“The current explanations may be divided into two categories. Of these the first includes what might be termed the superficial theories. Thus it is commonly stated that the outbreak of a crisis is due to lack of confidence,--as if the lack of confidence was not in itself the very thing which needs to be explained. Of still slighter value is the attempt to associate a crisis with some particular governmental policy, or with some action of a country’s executive. Such puerile interpretations have commonly been confined to countries like the United States, where the political passions of democracy have had the fullest way. Thus the crisis of 1893 was ascribed by the Republicans to the impending Democratic tariff of 1894; and the crisis of 1907 has by some been termed the ‘[Theodore] Roosevelt panic,” utterly oblivious of the fact that from the time of President Jackson, who was held responsible for the troubles of 1837, every successive crisis had had its presidential scapegoat, and has been followed by a political revulsion. Opposed to these popular, but wholly unfounded interpretations, is the second class of explanations, which seek to burrow beneath the surface and to discover the more occult and fundamental causes of the periodicity of crises.”

Scholars ignore superficial explanations in the effort to seek good and truth. The problem of economic analysis of the credit/dollar crisis is the lack of a structural model with which to attempt empirical determination of causes (Gorton and Metrick 2010SB). There would still be doubts even with a well-specified structural model because samples of economic events do not typically permit separating causes and effects. There is also confusion is separating the why of the crisis and how it started and propagated, all of which are extremely important.

In true heritage of the principles of Seligman (1908), Gorton (2009EFM) discovers a prime causal driver of the credit/dollar crisis. The objective of subprime and Alt-A mortgages was to facilitate loans to populations with modest means so that they could acquire a home. These borrowers would not receive credit because of (1) lack of funds for down payments; (2) low credit rating and information; (3) lack of information on income; and (4) errors or lack of other information. Subprime mortgage “engineering” was based on the belief that both lender and borrower could benefit from increases in house prices over the short run. The initial mortgage would be refinanced in two or three years depending on the increase of the price of the house. According to Gorton (2009EFM, 13, 16):

“The outstanding amounts of Subprime and Alt-A [mortgages] combined amounted to about one quarter of the $6 trillion mortgage market in 2004-2007Q1. Over the period 2000-2007, the outstanding amount of agency mortgages doubled, but subprime grew 800%! Issuance in 2005 and 2006 of Subprime and Alt-A mortgages was almost 30% of the mortgage market. Since 2000 the Subprime and Alt-A segments of the market grew at the expense of the Agency (i.e., the government sponsored entities of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) share, which fell from almost 80% (by outstanding or issuance) to about half by issuance and 67% by outstanding amount. The lender’s option to rollover the mortgage after an initial period is implicit in the subprime mortgage. The key design features of a subprime mortgage are: (1) it is short term, making refinancing important; (2) there is a step-up mortgage rate that applies at the end of the first period, creating a strong incentive to refinance; and (3) there is a prepayment penalty, creating an incentive not to refinance early.”

The prime objective of successive administrations in the US during the past 20 years and actually since the times of Roosevelt in the 1930s has been to provide “affordable” financing for the “American dream” of home ownership. The US housing finance system is mixed with public, public/private and purely private entities. The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system was established by Congress in 1932 that also created the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 with the objective of insuring homes against default. In 1938, the government created the Federal National Mortgage Association, or Fannie Mae, to foster a market for FHA-insured mortgages. Government-insured mortgages were transferred from Fannie Mae to the Government National Mortgage Association, or Ginnie Mae, to permit Fannie Mae to become a publicly-owned company. Securitization of mortgages began in 1970 with the government charter to the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, or Freddie Mac, with the objective of bundling mortgages created by thrift institutions that would be marketed as bonds with guarantees by Freddie Mac (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 42-8). In the third quarter of 2008, total mortgages in the US were $12,057 billion of which 43.5 percent, or $5423 billion, were retained or guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 45). In 1990, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had a share of only 25.4 percent of total mortgages in the US. Mortgages in the US increased from $6922 billion in 2002 to $12,088 billion in 2007, or by 74.6 percent, while the retained or guaranteed portfolio of Fannie and Freddie rose from $3180 billion in 2002 to $4934 billion in 2007, or by 55.2 percent.

According to Pinto (2008) in testimony to Congress: