Recovery without Hiring, Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs, Youth and Middle-age Unemployment, United States International Trade, Peaking Valuations of Risk Financial Assets, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013

Executive Summary

I Recovery without Hiring

IA1 Hiring Collapse

IA2 Labor Underutilization

IA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Job

IA4 Youth and Middle-Aged Unemployment

II United States International Trade

IIA1 United States International Trade

IIA2 United States Import and Export Prices

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

IV Global Inflation. There is inflation everywhere in the world economy, with slow growth and persistently high unemployment in advanced economies. Table IV-1, updated with every blog comment, provides the latest annual data for GDP, consumer price index (CPI) inflation, producer price index (PPI) inflation and unemployment (UNE) for the advanced economies, China and the highly-indebted European countries with sovereign risk issues. The table now includes the Netherlands and Finland that with Germany make up the set of northern countries in the euro zone that hold key votes in the enhancement of the mechanism for solution of sovereign risk issues (Peter Spiegel and Quentin Peel, “Europe: Northern Exposures,” Financial Times, Mar 9, 2011 http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/55eaf350-4a8b-11e0-82ab-00144feab49a.html#axzz1gAlaswcW). Newly available data on inflation is considered below in this section. Data in Table IV-1 for the euro zone and its members are updated from information provided by Eurostat but individual country information is provided in this section as soon as available, following Table IV-1. Data for other countries in Table IV-1 are also updated with reports from their statistical agencies. Economic data for major regions and countries is considered in Section V World Economic Slowdown following with individual country and regional data tables.

Table IV-1, GDP Growth, Inflation and Unemployment in Selected Countries, Percentage Annual Rates

| GDP | CPI | PPI | UNE | |

| US | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 7.6 |

| Japan | 0.5 | -0.7 | -0.5 | 4.3 |

| China | 7.9 | 2.1 | -1.9 | |

| UK | 0.2 | 2.8* CPIH 2.6 | 2.3 output | 7.8 |

| Euro Zone | -0.9 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 12.0 |

| Germany | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 5.4 |

| France | -0.3 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 10.8 |

| Nether-lands | -0.9 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 6.2 |

| Finland | -1.4 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 8.1 |

| Belgium | -0.4 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 8.1 |

| Portugal | -3.8 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 17.5 |

| Ireland | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 14.2 |

| Italy | -2.7 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 11.6 |

| Greece | -6.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | NA |

| Spain | -1.9 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 26.3 |

Notes: GDP: rate of growth of GDP; CPI: change in consumer price inflation; PPI: producer price inflation; UNE: rate of unemployment; all rates relative to year earlier

*Office for National Statistics http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/cpi/consumer-price-indices/february-2013/index.html **Core

PPI http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ppi2/producer-price-index/february-2013/index.html

Source: EUROSTAT http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/eurostat/home/; country statistical sources http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

Table IV-1 shows the simultaneous occurrence of low growth, inflation and unemployment in advanced economies. The US grew at 1.7 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011 (Table 8 in http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp4q12_3rd.pdf http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html). Japan’s GDP grew 0.3 percent in IVQ2011 relative to IVQ2010 and contracted 1.6 percent in IIQ2011 relative to IIQ2010 because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011 but grew at the seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 10.6 percent in IIIQ2011, increasing at the SAAR of 0.4 percent in IVQ 2011, increasing at the SAAR of 6.1 percent in IQ2012 and decreasing at 0.9 percent in IIQ2012 but contracting at the SAAR of 3.7 percent in IIIQ2012 and increasing at the SAAR of 0.2 percent in IVQ2012 (see Section VB http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.htm and earlier at

http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/recovery-without-hiring-united-states.html); the UK grew at minus 0.3 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IIIQ2012 and GDP increased 0.2 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html); and the Euro Zone grew at minus 0.6 percent in IVQ2012 and minus 0.9 percent in IVQ2012 relative to IVQ2011 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or_8.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.htm). These are stagnating or “growth recession” rates, which are positive or about nil growth rates with some contractions that are insufficient to recover employment. The rates of unemployment are quite high: 7.6 percent in the US but 18.2 percent for unemployment/underemployment or job stress of 29.6 million (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.htm), 4.3 percent for Japan (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html), 7.8 percent for the UK with high rates of unemployment for young people (see the labor statistics of the UK in Subsection VH http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/united-states-commercial-banks-assets.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html). Twelve-month rates of inflation have been quite high, even when some are moderating at the margin: 2.0 percent in the US, -0.7 percent for Japan, 2.1 percent for China, 1.8 percent for the Euro Zone and 2.8 percent for the UK. Stagflation is still an unknown event but the risk is sufficiently high to be worthy of consideration (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/risk-aversion-and-stagflation.html). The analysis of stagflation also permits the identification of important policy issues in solving vulnerabilities that have high impact on global financial risks. There are six key interrelated vulnerabilities in the world economy that have been causing global financial turbulence: (1) sovereign risk issues in Europe resulting from countries in need of fiscal consolidation and enhancement of their sovereign risk ratings (see Section III and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html); (2) the tradeoff of growth and inflation in China now with change in growth strategy to domestic consumption instead of investment and political developments in a decennial transition; (3) slow growth by repression of savings with de facto interest rate controls (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html), weak hiring with the loss of 10 million full-time jobs (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html) and continuing job stress of 24 to 30 million people in the US and stagnant wages in a fractured job market (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.htm); (4) the timing, dose, impact and instruments of normalizing monetary and fiscal policies (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/11/united-states-unsustainable-fiscal.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/08/expanding-bank-cash-and-deposits-with.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/united-states-gdp-growth-standstill.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/global-financial-risks-and-fed.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/policy-inflation-growth-unemployment.html) in advanced and emerging economies; (5) the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011 that had repercussions throughout the world economy because of Japan’s share of about 9 percent in world output, role as entry point for business in Asia, key supplier of advanced components and other inputs as well as major role in finance and multiple economic activities (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704461304576216950927404360.html?mod=WSJ_business_AsiaNewsBucket&mg=reno-wsj); and (6) geopolitical events in the Middle East.

In the effort to increase transparency, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) provides both economic projections of its participants and views on future paths of the policy rate that in the US is the federal funds rate or interest on interbank lending of reserves deposited at Federal Reserve Banks. These projections and views are discussed initially followed with appropriate analysis.

Charles Evans, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, proposed an “economic state-contingent policy” or “7/3” approach (Evans 2012 Aug 27):

“I think the best way to provide forward guidance is by tying our policy actions to explicit measures of economic performance. There are many ways of doing this, including setting a target for the level of nominal GDP. But recognizing the difficult nature of that policy approach, I have a more modest proposal: I think the Fed should make it clear that the federal funds rate will not be increased until the unemployment rate falls below 7 percent. Knowing that rates would stay low until significant progress is made in reducing unemployment would reassure markets and the public that the Fed would not prematurely reduce its accommodation.

Based on the work I have seen, I do not expect that such policy would lead to a major problem with inflation. But I recognize that there is a chance that the models and other analysis supporting this approach could be wrong. Accordingly, I believe that the commitment to low rates should be dropped if the outlook for inflation over the medium term rises above 3 percent.

The economic conditionality in this 7/3 threshold policy would clarify our forward policy intentions greatly and provide a more meaningful guide on how long the federal funds rate will remain low. In addition, I would indicate that clear and steady progress toward stronger growth is essential.”

Evans (2012Nov27) modified the “7/3” approach to a “6.5/2.5” approach:

“I have reassessed my previous 7/3 proposal. I now think a threshold of 6-1/2 percent for the unemployment rate and an inflation safeguard of 2-1/2 percent, measured in terms of the outlook for total PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index) inflation over the next two to three years, would be appropriate.”

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided at its meeting on Dec 12, 2012 to implement the “6.5/2.5” approach (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20121212a.htm):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

Another rising risk is division within the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on risks and benefits of current policies as expressed in the minutes of the meeting held on Jan 29-30, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20130130.pdf 13):

“However, many participants also expressed some concerns about potential costs and risks arising from further asset purchases. Several participants discussed the possible complications that additional purchases could cause for the eventual withdrawal of policy accommodation, a few mentioned the prospect of inflationary risks, and some noted that further asset purchases could foster market behavior that could undermine financial stability. Several participants noted that a very large portfolio of long-duration assets would, under certain circumstances, expose the Federal Reserve to significant capital losses when these holdings were unwound, but others pointed to offsetting factors and one noted that losses would not impede the effective operation of monetary policy.

Jon Hilsenrath and Victoria McGrane, writing on “Fed slip over how long to keep cash spigot open,” published on Feb 20, 2013 in the Wall street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323511804578298121033876536.html), analyze the minutes of the Fed, comments by members of the FOMC and data showing increase in holdings of riskier debt by investors, record issuance of junk bonds, mortgage securities and corporate loans. Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Jobs upturn isn’t enough to satisfy Fed,” on Mar 8, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324582804578348293647760204.html), finds that much stronger labor market conditions are required for the Fed to end quantitative easing. Unconventional monetary policy with zero interest rates and quantitative easing is quite difficult to unwind because of the adverse effects of raising interest rates on valuations of risk financial assets and home prices, including the very own valuation of the securities held outright in the Fed balance sheet. Gradual unwinding of 1 percent fed funds rates from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004 by seventeen consecutive increases of 25 percentage points from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006 to reach 5.25 percent caused default of subprime mortgages and adjustable-rate mortgages linked to the overnight fed funds rate. The zero interest rate has penalized liquidity and increased risks by inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to speculative positions in risk financial assets. There is no exit from zero interest rates without provoking another financial crash.

Unconventional monetary policy will remain in perpetuity, or QE→∞, changing to a “growth mandate.” There are two reasons explaining unconventional monetary policy of QE→∞: insufficiency of job creation to reduce unemployment/underemployment at current rates of job creation; and growth of GDP at 1.5 percent, which is well below 3.0 percent estimated by Lucas (2011May) from 1870 to 2010. Unconventional monetary policy interprets the dual mandate of low inflation and maximum employment as mainly a “growth mandate” of forcing economic growth in the US at a rate that generates full employment. A hurdle to this “growth mandate” is that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent on average during cyclical expansions in the postwar period while growth has been at only 2.1 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 14 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2012. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing have not provided the impulse for growth and were not required in past successful cyclical expansions.

First, the number of nonfarm jobs and private jobs created has been declining in 2012 from 311,000 in Jan 2012 to 87,000 in Jun, 138,000 in Sep, 160,000 in Oct, 247,000 in Nov and 219,000 in Dec 2012 for total nonfarm jobs and from 323,000 in Jan 2012 to 78,000 in Jun, 118,000 in Sep, 217,000 in Oct, 256,000 in Nov and 224,000 in Dec 2012 for private jobs. Average new nonfarm jobs in the quarter Dec 2011 to Feb 2012 were 270,667 per month, declining to average 159,909 per month in the eleven months from Mar 2012 to Jan 2013. Average new private jobs in the quarter Dec 2011 to Feb 2012 were 279,000 per month, declining to average 167,727 per month in the eleven months from Mar 2012 to Jan 2013. The number of 164,000 new private new jobs created in Jan 2013 is lower than the average 167,727 per month created from Mar 2012 to Jan 2013. New farm jobs created in Feb 2013 were 268,000 and 254,000 in private jobs, which exceeds the average for the prior eleven months. In Mar 2013 the US economy created 88,000 new farm jobs, which is 52 percent of the average of 169,000 jobs per month created in the past 12 months (page 2 http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf). The US labor force increased from 153.617 million in 2011 to 154.975 million in 2012 by 1.358 million or 113,167 per month. The average increase of nonfarm jobs in the six months from Oct 2012 to Mar 2013 was 188,333, which is a rate of job creation inadequate to reduce significantly unemployment and underemployment in the United States because of 113,167 new entrants in the labor force per month with 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed. The difference between the average increase of 188,333 new private nonfarm jobs per month in the US from Oct 2012 to Mar 2013 and the 113,167 average monthly increase in the labor force from 2011 to 2012 is 75,166 monthly new jobs net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force. There are 29.6 million in job stress in the US currently. The provision of 75,166 new jobs per month net of absorption of new entrants in the labor force would require 393 months to provide jobs for the unemployed and underemployed (29.550 million divided by 75,166) or 32.8 years (393 divided by 12). The civilian labor force of the US in Mar 2013 not seasonally adjusted stood at 154.512 million with 11.815 million unemployed or effectively 19.490 million unemployed in this blog’s calculation by inferring those who are not searching because they believe there is no job for them for effective labor force of 162.187 million. Reduction of one million unemployed at the current rate of job creation without adding more unemployment requires 1.1 years (1 million divided by product of 75,166 by 12, which is 901,992). Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would be equivalent to unemployment of only 7.726 million (0.05 times labor force of 154.512 million) for new net job creation of 4.089 million (11.815 million unemployed minus 7.726 million unemployed at rate of 5 percent) that at the current rate would take 4.5 years (4.089 million divided by 901.992). Under the calculation in this blog there are 19.490 million unemployed by including those who ceased searching because they believe there is no job for them and effective labor force of 162.187 million. Reduction of the rate of unemployment to 5 percent of the labor force would require creating 11.381 million jobs net of labor force growth that at the current rate would take 12.6 years (19.490 million minus 0.05(162.187 million) or 11.381 million divided by 901,992, using LF PART 66.2% and Total UEM in Table I-4). These calculations assume that there are no more recessions, defying United States economic history with periodic contractions of economic activity when unemployment increases sharply. The number employed in the US fell from 147.118 million in Nov 2007 to 142.698 million in Mar 2013, by 4.420 million, or decline of 3.0 percent, while the noninstitutional population increased from 232.939 million in Nov 2007 to 244.995 million in Mar 2013, by 12.056 million or increase of 5.2 percent, using not seasonally adjusted data. There is actually not sufficient job creation to merely absorb new entrants in the labor force because of those dropping from job searches, worsening the stock of unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs.

Second, calculations show that actual growth is around 1.6 to 2.1 percent per year. This rate is well below 3 percent per year in trend from 1870 to 2010, which has been always recovered after events such as wars and recessions (Lucas 2011May). Growth is not only mediocre but sharply decelerating to a rhythm that is not consistent with reduction of unemployment and underemployment of 30.8 million people corresponding to 19.0 percent of the effective labor force of the United States (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). In the four quarters of 2011 and the four quarters of 2012, US real GDP grew at the seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent rates of 0.1 percent in the first quarter of 2011 (IQ2011), 2.5 percent in IIQ2011, 1.3 percent in IIIQ2011, 4.1 percent in IVQ2011, 2.0 percent in IQ2012, 1.3 percent in IIQ2012, revised 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012 and 0.4 percent in IVQ2012. GDP growth in IIIQ2012 was revised from 2.7 percent seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) to 3.1 percent but mostly because of contribution of 0.73 percentage points of inventory accumulation and one-time contribution of 0.64 percentage points of expenditures in national defense that without them would have reduced growth from 3.1 percent to 1.73 percent. Equally, GDP growth in IVQ2012 is measured in the third estimate as 0.4 percent but mostly because of deduction of divestment of inventories of 1.52 percentage points and deduction of one-time national defense expenditures of 1.28 percentage points. The annual equivalent rate of growth of GDP for the four quarters of 2011 and the four quarters of 2012 is 1.8 percent, obtained as follows. Discounting 0.1 percent to one quarter is 0.025 percent {[(1.001)1/4 -1]100 = 0.025}; discounting 2.5 percent to one quarter is 0.62 percent {[(1.025)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 – 1]100}; discounting 4.1 percent to one quarter is 1.0 {[(1.04)1/4 -1]100; discounting 2.0 percent to one quarter is 0.50 percent {[(1.020)1/4 -1]100); discounting 1.3 percent to one quarter is 0.32 percent {[(1.013)1/4 -1]100}; discounting 3.1 percent to one quarter is 0.77 {[(1.031)1/4 -1]100); and discounting 0.4 percent to one quarter is 0.1 percent {[(1.004)1/4 – 1]100}. Real GDP growth in the four quarters of 2011 and the four quarters of 2012 accumulated to 3.7 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001) - 1]100 = 3.7%}. This is equivalent to growth from IQ2011 to IVQ2012 obtained by dividing the seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of IVQ2012 of $13,665.4 billion by the SAAR of IVQ2010 of $13,181.2 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1 and Table I-6 below) and expressing as percentage {[($13,665.4/$13,181.2) - 1]100 = 3.7%} with a minor rounding discrepancy. The growth rate in annual equivalent for the four quarters of 2011 and the four quarters of 2012 is 1.8 percent {[(1.00025 x 1.0062 x 1.0032 x 1.010 x 1.005 x 1.0032 x 1.0077 x 1.001)4/8 -1]100 = 1.8%], or {[($13,665.4/$13,181.2)]4/8-1]100 = 1.8%} dividing the SAAR of IVQ2012 by the SAAR of IVQ2010 in Table I-6 below, obtaining the average for eight quarters and the annual average for one year of four quarters. Growth in the four quarters of 2012 accumulates to 1.7 percent {[(1.02)1/4(1.013)1/4(1.031)1/4(1.004)1/4 -1]100 = 1.7%}. This is equivalent to dividing the SAAR of $13,665.4 billion for IVQ2012 in Table I-6 by the SAAR of $13,441.0 billion in IVQ2011 except for a rounding discrepancy to obtain 1.7 percent {[($13,665.4/$13,441.0) – 1]100 = 1.7%}. The US economy is still close to a standstill especially considering the GDP report in detail. Excluding growth at the SAAR of 2.5 percent in IIQ2011 and 4.1 percent in IVQ2011 while converting growth in IIIQ2012 to 1.73 percent by deducting from 3.1 percent one-time inventory accumulation of 0.73 percentage points and national defense expenditures of 0.64 percentage points and converting growth in IVQ2012 by adding 1.52 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.28 percentage points of national defense expenditure reductions to obtain 3.2 percent, the US economy grew at 1.6 percent in the remaining six quarters {[(1.00025x1.0032x1.005x1.0032x1.0043x1.0079)4/6 – 1]100 = 1.6%} with declining growth trend in three consecutive quarters from 4.1 percent in IVQ2011, to 2.0 percent in IQ2012, 1.3 percent in IIQ2012, 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012 that is more like 1.73 percent without inventory accumulation and national defense expenditures and 0.4 percent in IVQ2012 that is more likely 3.2 percent by adding 1.52 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.28 percentage points of national defense expenditures. Weakness of growth is more clearly shown by adjusting the exceptional one-time contributions to growth from items that are not aggregate demand: 2.53 percentage points contributed by inventory change to growth of 4.1 percent in IVQ2011; 0.64 percentage points contributed by expenditures in national defense together with 0.73 points of inventory accumulation to growth of 3.1 percent in IIIQ2012; and deduction of 1.52 percentage points of inventory divestment and 1.28 percentage points of national defense expenditure reductions. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) of the US Department of Commerce released on Wed Jan 30, 2012, the third estimate of GDP for IVQ2012 at 0.4 percent seasonally-adjusted annual rate (SAAR) (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp4q12_3rd.pdf). In the four quarters of 2012, the US economy is growing at the annual equivalent rate of 2.1 percent {([(1.021/4(1.013)1/4(1.0173)1/4(1.032)1/4]-1)100 = 2.1%} by excluding inventory accumulation of 0.73 percentage points and exceptional defense expenditures of 0.64 percentage points from growth 3.1 percent at SAAR in IIIQ2012 to obtain adjusted 1.73 percent SSAR and adding 1.52 percentage points of national defense expenditure reductions and 1.28 percentage points of inventory divestment to growth of 0.4 percent SAAR in IVQ2012 to obtain 3.2 percent.

In fact, it is evident to the public that this policy will be abandoned if inflation costs rise. There is concern of the production and employment costs of controlling future inflation. Even if there is no inflation, QE→∞ cannot be abandoned because of the fear of rising interest rates. The economy would operate in an inferior allocation of resources and suboptimal growth path, or interior point of the production possibilities frontier where the optimum of productive efficiency and wellbeing is attained, because of the distortion of risk/return decisions caused by perpetual financial repression. Not even a second-best allocation is feasible with the shocks to efficiency of financial repression in perpetuity.

The statement of the FOMC at the conclusion of its meeting on Dec 12, 2012, revealed policy intentions (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20121212a.htm) practically unchanged in the statement at the conclusion of its meeting on Jan 30, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130130a.htm) and at its meeting on Mar 20, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130320a.htm):

“Release Date: Mar 20, 2013

For immediate release

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in January suggests a return to moderate economic growth following a pause late last year. Labor market conditions have shown signs of improvement in recent months but the unemployment rate remains elevated. Household spending and business fixed investment advanced, and the housing sector has strengthened further, but fiscal policy has become somewhat more restrictive. Inflation has been running somewhat below the Committee's longer-run objective, apart from temporary variations that largely reflect fluctuations in energy prices. Longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee expects that, with appropriate policy accommodation, economic growth will proceed at a moderate pace and the unemployment rate will gradually decline toward levels the Committee judges consistent with its dual mandate. The Committee continues to see downside risks to the economic outlook. The Committee also anticipates that inflation over the medium term likely will run at or below its 2 percent objective.

To support a stronger economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with its dual mandate, the Committee decided to continue purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month and longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $45 billion per month. The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. Taken together, these actions should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative.

The Committee will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments in coming months. The Committee will continue its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate, until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. In determining the size, pace, and composition of its asset purchases, the Committee will continue to take appropriate account of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases as well as the extent of progress toward its economic objectives.

To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored. In determining how long to maintain a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy, the Committee will also consider other information, including additional measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent. “

There are several important issues in this statement.

- Mandate. The FOMC pursues a policy of attaining its “dual mandate” of (http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm):

“Conducting the nation's monetary policy by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”

- Open-ended Quantitative Easing or QE∞. Earlier programs are continued with an additional open-ended $85 billion of bond purchases per month: “To support a stronger economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with its dual mandate, the Committee decided to continue purchasing additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month and longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $45 billion per month.”

- Advance Guidance on “6 ¼ 2 ½ “Rule. Policy will be accommodative even after the economy recovers satisfactorily: “To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

- Monitoring and Policy Focus on Jobs. The FOMC reconsiders its policy continuously in accordance with available information: “In determining how long to maintain a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy, the Committee will also consider other information, including additional measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent.”

Unconventional monetary policy drives wide swings in allocations of positions into risk financial assets that generate instability instead of intended pursuit of prosperity without inflation. There is insufficient knowledge and imperfect tools to maintain the gap of actual relative to potential output constantly at zero while restraining inflation in an open interval of (1.99, 2.0). Symmetric targets appear to have been abandoned in favor of a self-imposed single jobs mandate of easing monetary policy even with the economy growing at or close to potential output that is actually a target of growth forecast. The impact on the overall economy and the financial system of errors of policy are magnified by large-scale policy doses of trillions of dollars of quantitative easing and zero interest rates. The US economy has been experiencing financial repression as a result of negative real rates of interest during nearly a decade and programmed in monetary policy statements until 2015 or, for practical purposes, forever. The essential calculus of risk/return in capital budgeting and financial allocations has been distorted. If economic perspectives are doomed until 2015 such as to warrant zero interest rates and open-ended bond-buying by “printing” digital bank reserves (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html; see Shultz et al 2012), rational investors and consumers will not invest and consume until just before interest rates are likely to increase. Monetary policy statements on intentions of zero interest rates for another three years or now virtually forever discourage investment and consumption or aggregate demand that can increase economic growth and generate more hiring and opportunities to increase wages and salaries. The doom scenario used to justify monetary policy accentuates adverse expectations on discounted future cash flows of potential economic projects that can revive the economy and create jobs. If it were possible to project the future with the central tendency of the monetary policy scenario and monetary policy tools do exist to reverse this adversity, why the tools have not worked before and even prevented the financial crisis? If there is such thing as “monetary policy science”, why it has such poor record and current inability to reverse production and employment adversity? There is no excuse of arguing that additional fiscal measures are needed because they were deployed simultaneously with similar ineffectiveness.

Table IV-2 provides economic projections of governors of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and regional presidents of Federal Reserve Banks released at the meeting of Mar 20, 2013. The Fed releases the data with careful explanations (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf). Columns “∆% GDP,” “∆% PCE Inflation” and “∆% Core PCE Inflation” are changes “from the fourth quarter of the previous year to the fourth quarter of the year indicated.” The GDP report for IVQ2012 is analyzed in Section I (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html

and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states_24.html) and the PCE inflation data from the report on personal income and outlays in Section IV (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html and earlier at (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html). The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides the third estimate of IVQ2012 GDP and annual for 2012 with the first estimate for IQ2013 be released on Apr 26 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/gdpnewsrelease.htm See Section I and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html). PCE inflation is the index of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) of the report of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) on “Personal Income and Outlays” (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/pinewsrelease.htm), which is analyzed in Section IV http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/mediocre-gdp-growth-at-16-to-20-percent.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html and the report for Nov 2012 at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states_24.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/12/mediocre-and-decelerating-united-states.html. The next report on “Personal Income and Outlays” for Mar will be released at 8:30 AM on Apr 29, 2013 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/pinewsrelease.htm). PCE core inflation consists of PCE inflation excluding food and energy. Column “UNEMP %” is the rate of unemployment measured as the average civilian unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of the year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides the Employment Situation Report with the civilian unemployment rate in the first Friday of every month, which is analyzed in this blog. The report for Jan 2013 was released on Feb 1, 2013 and analyzed in this blog (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.html). The report for Feb 2013 was released on Mar 8, 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/ces/) and analyzed in this blog on Mar 10, 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/thirty-one-million-unemployed-or.htm). The report for Mar 2013 was released on Apr 5, 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/ces/) and analyzed in this blog in the comment on Apr 7 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/04/thirty-million-unemployed-or.html). “Longer term projections represent each participant’s assessment of the rate to which each variable would be expected to converge under appropriate monetary policy and in the absence of further shocks to the economy” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20121212.pdf).

It is instructive to focus on 2013 as 2014, 2015 and longer term are too far away, and there is not much information even on what will happen in 2013 and beyond. The central tendency should provide reasonable approximation of the view of the majority of members of the FOMC but the second block of numbers provides the range of projections by FOMC participants. The first row for each year shows the projection introduced after the meeting of Mar 20, 2012 and the second row “PR” the projection of the Dec 12, 2012 meeting. There are three major changes in the view.

1. Growth “∆% GDP.” The FOMC has reduced the forecast of GDP growth in 2013 from 2.3 to 3.0 percent at the meeting in Dec 2012 to 2.3 to 2.8 percent at the meeting on Mar 20, 2013.

2. Rate of Unemployment “UNEM%.” The FOMC reduced the forecast of the rate of unemployment from 7.4 to 7.7 percent at the meeting on Dec 12, 2012 to 7.3 to 7.5 percent at the meeting on Mar 20, 2013.

3. Inflation “∆% PCE Inflation.” The FOMC changed the forecast of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation from 1.3 to 2.0 percent at the meeting on Dec 12, 2012 to 1.3 to 1.7 percent at the meeting on Mar 20, 2013.

4. Core Inflation “∆% Core PCE Inflation.” Core inflation is PCE inflation excluding food and energy. There is again not much of a difference of the projection that changed from 1.6 to 1.9 percent at the meeting on Dec 12, 2012 to 1.5 to 1.6 percent at the meeting on Mar 20, 2013.

Table IV-2, US, Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents in FOMC, Dec 2012 and Mar 2012

| ∆% GDP | UNEM % | ∆% PCE Inflation | ∆% Core PCE Inflation | |

| Central | ||||

| 2013 | 2.3 to 2.8 | 7.3 to 7.5 | 1.3 to 1.7 | 1.5 to 1.6 1.6 to 1.9 |

| 2014 | 2.9 to 3.4 | 6.7 to 7.0 | 1.5 to 2.0 | 1.7 to 2.0 |

| 2015 | 2.9 to 3.7 3.0 to 3.7 | 6.0 to 6.5 6.0 to 6.6 | 1.7 to 2.0 1.7 to 2.0 | 1.8 to 2.1 1.8 to 2.0 |

| Longer Run Sep PR | 2.3 to 2.5 2.3 to 2.5 | 5.2 to 6.0 5.2 to 6.0 | 2.0 2.0 | |

| Range | ||||

| 2013 | 2.0 to 3.0 | 6.9 to 7.6 | 1.3 to 2.0 | 1.5 to 2.0 |

| 2014 | 2.6 to 3.8 | 6.1 to 7.1 | 1.4 to 2.1 | 1.5 to 2.1 |

| 2015 Dec PR | 2.5 to 3.8 2.5 to 4.2 | 5.7 to 6.5 5.7 to 6.8 | 1.6 to 2.6 1.5 to 2.2 | 1.7 to 2.6 1.7 to 2.2 |

| Longer Run Dec PR | 2.0 to 3.0 2.2 to 3.0 | 5.0 to 6.0 5.0 to 6.0 | 2.0 2.0 |

Notes: UEM: unemployment; PR: Projection

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

Another important decision at the FOMC meeting on Jan 25, 2012, is formal specification of the goal of inflation of 2 percent per year but without specific goal for unemployment (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20120125c.htm):

“Following careful deliberations at its recent meetings, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has reached broad agreement on the following principles regarding its longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy. The Committee intends to reaffirm these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual organizational meeting each January.

The FOMC is firmly committed to fulfilling its statutory mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity facilitates well-informed decision making by households and businesses, reduces economic and financial uncertainty, increases the effectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society.

Inflation, employment, and long-term interest rates fluctuate over time in response to economic and financial disturbances. Moreover, monetary policy actions tend to influence economic activity and prices with a lag. Therefore, the Committee's policy decisions reflect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments of the balance of risks, including risks to the financial system that could impede the attainment of the Committee's goals.

The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for inflation. The Committee judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve's statutory mandate. Communicating this inflation goal clearly to the public helps keep longer-term inflation expectations firmly anchored, thereby fostering price stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhancing the Committee's ability to promote maximum employment in the face of significant economic disturbances.

The maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labor market. These factors may change over time and may not be directly measurable. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a fixed goal for employment; rather, the Committee's policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the maximum level of employment, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments. Information about Committee participants' estimates of the longer-run normal rates of output growth and unemployment is published four times per year in the FOMC's Summary of Economic Projections. For example, in the most recent projections, FOMC participants' estimates of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment had a central tendency of 5.2 percent to 6.0 percent, roughly unchanged from last January but substantially higher than the corresponding interval several years earlier.

In setting monetary policy, the Committee seeks to mitigate deviations of inflation from its longer-run goal and deviations of employment from the Committee's assessments of its maximum level. These objectives are generally complementary. However, under circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it follows a balanced approach in promoting them, taking into account the magnitude of the deviations and the potentially different time horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate. ”

The probable intention of this specific inflation goal is to “anchor” inflationary expectations. Massive doses of monetary policy of promoting growth to reduce unemployment could conflict with inflation control. Economic agents could incorporate inflationary expectations in their decisions. As a result, the rate of unemployment could remain the same but with much higher rate of inflation (see Kydland and Prescott 1977 and Barro and Gordon 1983; http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html See Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 99-116). Strong commitment to maintaining inflation at 2 percent could control expectations of inflation.

The FOMC continues its efforts of increasing transparency that can improve the credibility of its firmness in implementing its dual mandate. Table IV-3 provides the views by participants of the FOMC of the levels at which they expect the fed funds rate in 2012, 2013, 2014 and the in the longer term. Table IV-3 is inferred from a chart provided by the FOMC with the number of participants expecting the target of fed funds rate (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf). There are 18 participants expecting the rate to remain at 0 to ¼ percent in 2013 and one to be higher in the interval below 1.0 percent. The rate would still remain at 0 to ¼ percent in 2014 for 14 participants with three expecting the rate to be in the range of 1.0 to 2.0 percent, one participant expecting rates at 0.5 to 1.0 percent and one participant expecting rates from 2.0 to 3.0. This table is consistent with the guidance statement of the FOMC that rates will remain at low levels until late in 2014. For 2015, nine participants expect rates to be below 1.0 percent while nine expect rates from 1.0 to 4.5 percent. In the long run, all 19 participants expect rates to be between 3.0 and 4.5 percent.

Table IV-3, US, Views of Target Federal Funds Rate at Year-End of Federal Reserve Board

Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents Participating in FOMC, June 20, 2012

| 0 to 0.25 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 1.0 to 1.5 | 1.0 to 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | 3.0 to 4.5 | |

| 2013 | 18 | 1 | ||||

| 2014 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 2015 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Longer Run | 19 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

Additional information is provided in Table IV-4 with the number of participants expecting increasing interest rates in the years from 2013 to 2015. It is evident from Table IV-4 that the prevailing view of the FOMC is for interest rates to continue at low levels in future years. This view is consistent with the economic projections of low economic growth, relatively high unemployment and subdued inflation provided in Table IV-2.

Table IV-4, US, Views of Appropriate Year of Increasing Target Federal Funds Rate of Federal

Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents Participating in FOMC, June 20, 2012

| Appropriate Year of Increasing Target Fed Funds Rate | Number of Participants |

| 2013 | 1 |

| 2014 | 4 |

| 2015 | 13 |

| 2016 | 1 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FOMC http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20130320.pdf

Inflation in advanced economies has been fluctuating in waves at the production level with alternating surges and moderation of commodity price shocks. Table IV-6 provides month and 12-month percentage rates of inflation of Japan’s corporate goods price index (CGPI). Inflation measured by the CGPI increased 0.1 percent in Mar 2013 and fell 0.5 percent in 12 months. Measured by 12-month rates, CGPI inflation increased from minus 0.2 percent in Jul 2010 to a high of 2.2 percent in Jul-Aug 2011 and declined to minus 0.5 percent in Mar 2013. Calendar-year inflation for 2012 is minus 0.9 percent and 1.5 percent for 2011, which is the highest after declines in 2009 and 2010 but lower than 4.6 percent in the commodity shock driven by zero interest rates during the global recession in 2008. Inflation of the corporate goods prices follows waves similar to those in other indices around the world (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/03/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html). In the first wave, annual equivalent inflation reached 5.9 percent in Jan-Apr 2011, driven by commodity price shocks of the carry trade from zero interest rates to commodity futures. In the second wave, carry trades were unwound because of risk aversion caused by the European debt crisis, resulting in average annual equivalent inflation of minus 1.2 percent in May-Jun 2011. In the third wave, renewed risk aversion caused annual equivalent decline of the CGPI of minus 2.2 percent in Jul-Nov 2011. In the fourth wave, continuing risk aversion resulted in annual equivalent inflation of minus 0.6 percent in Dec 2011 to Jan 2012. In the fifth wave, renewed risk appetite resulted in annual equivalent inflation of 2.0 percent in Feb-Apr 2012. In the sixth wave, annual equivalent inflation dropped to minus 5.8 percent in May-Jul 2012. In the seventh wave, annual equivalent inflation jumped to 3.0 percent in Aug-Sep 2012. In the eighth wave, annual equivalent inflation was minus 3.0 percent in Oct-Nov 2012 in a new round of risk aversion. In the ninth wave, annual equivalent inflation returned at 3.7 percent in Dec 2012-Mar 2013. Unconventional monetary policies of zero interest rates and quantitative easing have created a difficult environment for economic and financial decisions with significant inflation volatility.

Table IV-5, Japan, Corporate Goods Price Index (CGPI) ∆%

| Month | Year | |

| Mar 2013 | 0.1 | -0.5 |

| Feb | 0.5 | -0.1 |

| Jan | 0.2 | -0.4 |

| Dec 2012 | 0.4 | -0.7 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Mar | 3.7 | |

| Nov | -0.1 | -1.1 |

| Oct | -0.4 | -1.1 |

| AE ∆% Oct-Nov | -3.0 | |

| Sep | 0.3 | -1.5 |

| Aug | 0.2 | -2.0 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Sep | 3.0 | |

| Jul | -0.5 | -2.3 |

| Jun | -0.6 | -1.5 |

| May | -0.4 | -0.9 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | -5.8 | |

| Apr | -0.2 | -0.7 |

| Mar | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Feb | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Apr | 2.0 | |

| Jan | -0.1 | 0.3 |

| Dec 2011 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Jan | -0.6 | |

| Nov | -0.1 | 1.3 |

| Oct | -0.8 | 1.3 |

| Sep | -0.2 | 2.0 |

| Aug | -0.1 | 2.2 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | -2.2 | |

| Jun | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| May | -0.2 | 1.6 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | -1.2 | |

| Apr | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| Mar | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Feb | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Jan | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 5.9 | |

| Dec 2010 | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| Nov | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Oct | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| Sep | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| Aug | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| Jul | 0.0 | -0.2 |

| Calendar Year | ||

| 2012 | -0.9 | |

| 2011 | 1.5 | |

| 2010 | -0.1 | |

| 2009 | -5.3 | |

| 2008 | 4.6 |

AE: annual equivalent

Source: Bank of Japan http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1303.pdf http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/index.htm/

Chart IV-1 of the Bank of Japan provides year-on-year percentage changes of the domestic and services Corporate Goods Price Index (CGPI) of Japan from 1970 to 2013. Percentage changes of inflation of services are not as sharp as those of goods. Japan had the same sharp waves of inflation during the 1970s as in the US (see Table IV-7 at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/recovery-without-jobs-stagnating-real_09.html). Behavior of the CGPI of Japan in the 1970s mirrors the Great Inflation episode in the United States with waves of inflation rising to two digits. Both political pressures and errors abounded in the unhappy stagflation of the 1970s also known as the US Great Inflation (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html and Appendix I The Great Inflation; see Taylor 1993, 1997, 1998LB, 1999, 2012FP, 2012Mar27, 2012Mar28, 2012JMCB and http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html). Inflation also collapsed in the beginning of the 1980s because of tight monetary policy in the US with focus on inflation instead of on the gap of actual relative to potential output. The areas in shade correspond to the dates of cyclical recessions. The salient event is the sharp rise of inflation of the domestic goods CGPI in 2008 during the global recession that was mostly the result of carry trades from fed funds rates collapsing to zero to long positions in commodity futures in an environment of relaxed financial risk appetite. The panic of toxic assets in banks to be withdrawn by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) (Cochrane and Zingales 2009) drove unusual risk aversion with unwinding of carry trades of exposures in commodities and other risk financial assets. Carry trades returned once TARP was clarified as providing capital to financial institutions and stress tests verified the soundness of US banks. The return of carry trades explains the rise of CGPI inflation after mid-2009. Inflation of the CGPI fluctuated with zero interest rates in alternating episodes of risk aversion and risk appetite.

Chart IV-1, Japan, Domestic Corporate Goods Price and Services Index, Year-on-Year Percentage Change, 1970-2013

Notes: Blue: Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index All Commodities; Red: Corporate Price Services Index

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

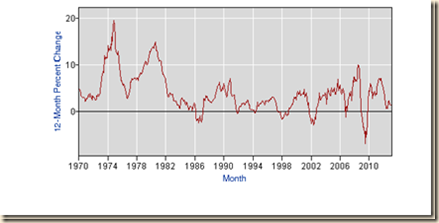

There is similar behavior of year-on-year percentage changes of the US producer price index from 1970 to 2013 in Chart IV-2 of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics as in Chart IV-1 with the domestic goods CGPI. The behavior of the CGPI of Japan in the 1970s is quite similar to that of the US PPI. The US producer price index increased together with the CGPI driven by the period of one percent fed funds rates from 2003 to 2004 inducing carry trades into commodity futures and other risk financial assets and the slow adjustment in increments of 25 basis points at every FOMC meeting from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006. There is also the same increase in inflation in 2008 during the global recession followed by collapse because of unwinding positions during risk aversion and new rise of inflation during risk appetite.

Chart IV-2, US, Producer Price Index Finished Goods, Year-on-Year Percentage Change, 1970-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Finer detail is provided by Chart IV-3 of the domestic CGPI from 2008 to 2013. The CGPI rose almost vertically in 2008 as the collapse of fed funds rates toward zero drove exposures in commodities and other risk financial assets because of risk appetite originating in the belief that the financial crisis was restricted to structured financial products and not to contracts negotiated in commodities and other exchanges. The panic with toxic assets in banks to be removed by TARP (Cochrane and Zingales 2009) caused unwinding carry trades in flight to US government obligations that drove down commodity prices and price indexes worldwide. Apparent resolution of the European debt crisis of 2010 drove risk appetite in 2011 with new carry trades from zero fed funds rates into commodity futures and other risk financial assets. Domestic CGPI inflation returned in waves with upward slopes during risk appetite and downward slopes during risk aversion.

Chart IV-3, Japan, Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

There is similar behavior of the US producer price index from 2008 to 2013 in Chart IV-4 as in the domestic CGPI in Chart IV-3. A major difference is the strong long-term trend in the US producer price index with oscillations originating mostly in bouts of risk aversion such as the downward slope in the final segment in Chart IV-4 followed by increasing slope during periods of risk appetite. Carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures and other risk financial assets drive the upward trend of the US producer price index while oscillations originate in alternating episodes of risk aversion and risk appetite.

Chart IV-4, US, Producer Price Index Finished Goods, Monthly, 2008-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

There was milder increase in Japan’s export corporate goods price index during the global recession in 2008 but similar sharp decline during the bank balance sheets effect in late 2008, as shown in Chart IV-5 of the Bank of Japan. Japan exports industrial goods whose prices have been less dynamic than those of commodities and raw materials. As a result, the export CGPI on the yen basis in Chart IV-5 trends down with oscillations after a brief rise in the final part of the recession in 2009. The export corporate goods price index fell from 104.8 in Jun 2009 to 94 in Feb 2012 or minus 10.3 percent and increased to 105.9 in Feb 2013 for a gain of 12.7 percent relative to Feb 2012 and 1.0 percent relative to Jun 2009. The choice of Jun 2009 is designed to capture the reversal of risk aversion beginning in Sep 2008 with the announcement of toxic assets in banks that would be withdrawn with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) (Cochrane and Zingales 2009). Reversal of risk aversion in the form of flight to the USD and obligations of the US government opened the way to renewed carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in risk financial assets such as commodities. Japan exports industrial products and imports commodities and raw materials.

Chart IV-5, Japan, Export Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Yen Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Chart IV-5A provides the export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency. The export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased from 97.9 in Jun 2009 to 102.3 in Feb 2012 or 4.5 percent but dropped to 101.5 in Feb 2013 or minus 0.8 percent relative to Feb 2012 and gained 3.7 percent relative to Jun 2009.

Chart IV-5A, Japan, Export Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Contract Currency Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Japan imports primary commodities and raw materials. As a result, the import corporate goods price index on the yen basis in Chart IV-6 shows an upward trend after the rise during the global recession in 2008 driven by carry trades from fed funds rates collapsing to zero into commodity futures and decline during risk aversion from late 2008 into beginning of 2008 originating in doubts about soundness of US bank balance sheets. More careful measurement should show that the terms of trade of Japan, export prices relative to import prices, declined during the commodity shocks originating in unconventional monetary policy. The decline of the terms of trade restricted potential growth of income in Japan. The import corporate goods price index on the yen basis increased from 93.5 in Jun 2009 to 106.4 in Feb 2012 or 13.8 percent and to 120.4 in Feb 2013 or gain of 13.2 percent relative to Feb 2012 and 28.8 percent relative to Jun 2009. Recent depreciation of the yen relative to the dollar explains the increase in imports in domestic yen prices.

Chart IV-6, Japan, Import Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Yen Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Chart IV-6A provides the import corporate goods price index on the contract currency basis. The import corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased from 86.2 in Jun 2009 to 115.8 in Feb 2012 or 34.3 percent and to 114.9 in Feb 2013 or minus 0.8 percent relative to Feb 2012 and gain of 33.3 percent relative to Jun 2009. There is evident deterioration of the terms of trade of Japan: the export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased 3.7 percent from Jun 2009 to Feb 2012 while the import corporate goods price index increased 33.3 percent. Prices of Japan’s exports of corporate goods, mostly industrial products, increased only 3.7 percent from Jun 2009 to Feb 2012, while imports of corporate goods, mostly commodities and raw materials increased 33.3 percent. Unconventional monetary policy induces carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in commodities that squeeze economic activity of industrial countries by increases in prices of imported commodities and raw materials during periods without risk aversion. Reversals of carry trades during periods of risk aversion decrease prices of exported commodities and raw materials that squeeze economic activity in economies exporting commodities and raw materials. Devaluation of the dollar by unconventional monetary policy could increase US competitiveness in world markets but economic activity is squeezed by increases in prices of imported commodities and raw materials. Unconventional monetary policy causes instability worldwide instead of the mission of central banks of promoting financial and economic stability.

Chart IV-6A, Japan, Import Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Contract Currency Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Chart IV-7 provides the monthly corporate goods price index (CGPI) of Japan from 1970 to 2013. Japan also experienced sharp increase in inflation during the 1970s as in the episode of the Great Inflation in the US. Monetary policy focused on accommodating higher inflation, with emphasis solely on the mandate of promoting employment, has been blamed as deliberate or because of model error or imperfect measurement for creating the Great Inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html and Appendix I The Great Inflation; see Taylor 1993, 1997, 1998LB, 1999, 2012FP, 2012Mar27, 2012Mar28, 2012JMCB and http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html). A remarkable similarity with US experience is the sharp rise of the CGPI of Japan in 2008 driven by carry trades from interest rapidly falling to zero to exposures in commodity futures during a global recession. Japan had the same sharp waves of consumer price inflation during the 1970s as in the US (see Table IV-7 at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/recovery-without-jobs-stagnating-real_09.html).

Chart IV-7, Japan, Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, 1970-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

The producer price index of the US from 1970 to 2013 in Chart IV-8 shows various periods of more rapid or less rapid inflation but no bumps. The major event is the decline in 2008 when risk aversion because of the global recession caused the collapse of oil prices from $148/barrel to less than $80/barrel with most other commodity prices also collapsing. The event had nothing in common with explanations of deflation but rather with the concentration of risk exposures in commodities after the decline of stock market indexes. Eventually, there was a flight to government securities because of the fears of insolvency of banks caused by statements supporting proposals for withdrawal of toxic assets from bank balance sheets in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), as explained by Cochrane and Zingales (2009). The bump in 2008 with decline in 2009 is consistent with the view that zero interest rates with subdued risk aversion induce carry trades into commodity futures.

Chart IV-8, US, Producer Price Index Finished Goods, Monthly, 1970-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Further insight into inflation of the corporate goods price index (CGPI) of Japan is provided in Table IV-6. Petroleum and coal with weight of 5.7 percent increased 0.6 percent in Mar 2013 and increased 1.6 percent in 12 months. Japan exports manufactured products and imports raw materials and commodities such that the country’s terms of trade, or export prices relative to import prices, deteriorate during commodity price increases. In contrast, prices of production machinery, with weight of 3.1 percent, increased 0.4 percent in Mar 2013 and increased 0.2 percent in 12 months. In general, most manufactured products have been experiencing negative or low increases in prices while inflation rates have been high in 12 months for products originating in raw materials and commodities. Ironically, unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing that intended to increase aggregate demand and GDP growth deteriorated the terms of trade of advanced economies with adverse effects on real income.

Table IV-6, Japan, Corporate Goods Prices and Selected Components, % Weights, Month and 12 Months ∆%

| Mar 2013 | Weight | Month ∆% | 12 Month ∆% |

| Total | 1000.0 | 0.1 | -0.5 |

| Food, Beverages, Tobacco, Feedstuffs | 137.5 | -0.1 | 0.4 |

| Petroleum & Coal | 57.4 | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Production Machinery | 30.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Electronic Components | 31.0 | -0.3 | -1.9 |

| Electric Power, Gas & Water | 52.7 | 0.4 | 4.2 |

| Iron & Steel | 56.6 | 0.3 | -7.5 |

| Chemicals | 92.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Transport | 136.4 | 0.0 | -2.2 |

Source: Bank of Japan http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1303.pdf

Percentage point contributions to change of the corporate goods price index (CGPI) in Mar 2013 are provided in Table IV-7 divided into domestic, export and import segments. In the domestic CGPI, increasing 0.1 percent in Mar 2013, the energy shock resulting from carry trades is evident in the contribution of 0.04 percentage points by petroleum and coal products in new carry trades of exposures in commodity futures. The exports CGPI decreased 0.2 percent on the basis of the contract currency with deduction of 0.08 percentage points by general purpose, production & business oriented machinery. The imports CGPI increased 0.3 percent on the contract currency basis. Petroleum, coal & natural gas added 0.45 percentage points because of new carry trades into energy commodity exposures. Shocks of risk aversion cause unwinding carry trades that result in declining commodity prices with resulting downward pressure on price indexes. The volatility of inflation adversely affects financial and economic decisions worldwide.

Table IV-7, Japan, Percentage Point Contributions to Change of Corporate Goods Price Index

| Groups Mar 2013 | Contribution to Change Percentage Points |

| A. Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index | Monthly Change: |

| Petroleum & Coal Products | 0.04 |

| Scrap & Waste | 0.03 |

| Chemicals & Related Products | 0.02 |

| Electric Power, Gas & Water | 0.02 |

| Iron & Steel | 0.02 |

| Nonferrous Metals | -0.02 |

| B. Export Price Index | Monthly Change: |

| General Purpose, Production & Business Oriented Machinery | -0.08 |

| Textiles | -0.07 |

| Metals & Related Products | -0.06 |

| Chemicals & Related Products | 0.07 |

| C. Import Price Index | Monthly Change: 0.3 % contract currency basis |

| Petroleum, Coal & Natural Gas | 0.45 |

| Metals & Related Products | -0.09 |

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1303.pdf

China is experiencing similar inflation behavior as the advanced economies in prior months in the form of declining commodity prices but differs in decreasing inflation of producer prices relative to a year earlier. As shown in Table IV-8, inflation of the price indexes for industry in Mar 2013 is 0.0 percent; 12-month inflation is minus 1.9 percent in Mar; and cumulative inflation in Jan-Mar 2013 relative to Jan-Mar 2012 is minus 1.7 percent. Inflation of segments in Mar 2013 in China is provided in Table IV-8 in column “Month Mar 2013 ∆%.” There were increases of prices of mining & quarrying of 0.4 percent in Mar but decrease of 5.6 percent in 12 months. Prices of consumer goods decreased 0.1 percent in Mar and increased 0.5 percent in 12 months. Prices of inputs in the purchaser price index decreased 0.1 percent in Mar and declined 2.0 percent in 12 months. Fuel and power increased 0.5 percent in Mar and declined 3.2 percent in 12 months. An important category of inputs for exports is textile raw materials, increasing 0.1 percent in Feb and declining 0.9 percent in 12 months.

Table IV-8, China, Price Indexes for Industry ∆%

| Month Mar 2013 ∆% | 12-Month Mar 2013 ∆% | Jan-Mar 2013/Jan-Mar 2012 ∆% | |

| I Producer Price Indexes | 0.0 | -1.9 | -1.7 |

| Means of Production | 0.0 | -2.7 | -2.5 |

| Mining & Quarrying | 0.4 | -5.6 | -5.3 |

| Raw Materials | 0.1 | -3.2 | -2.7 |

| Processing | -0.1 | -2.1 | -2.1 |

| Consumer Goods | -0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Food | -0.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Clothing | -0.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Daily Use Articles | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Durable Consumer Goods | -0.1 | -0.8 | -0.9 |

| II Purchaser Price Indexes | -0.1 | -2.0 | -1.9 |

| Fuel and Power | 0.5 | -3.2 | -2.9 |

| Ferrous Metals | 0.1 | -5.0 | -5.6 |

| Nonferrous Metals | -1.1 | -3.7 | -2.6 |

| Raw Chemical Materials | -0.2 | -3.1 | -3.1 |

| Wood & Pulp | 0.4 | -0.2 | -0.4 |

| Building Materials | -0.3 | -2.0 | -1.7 |

| Other Industrial Raw Materials | 0.1 | -0.7 | -0.8 |

| Agricultural | -0.6 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Textile Raw Materials | 0.1 | -0.9 | -0.9 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/

China’s producer price inflation follows waves similar to those around the world but with declining trend since May 2012, as shown in Table IV-9. In the first wave, annual equivalent inflation was 6.4 percent in Jan-Jun 2011, driven by carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures. In the second wave, risk aversion unwound carry trades, resulting in annual equivalent inflation of minus 3.1 percent in Jul-Nov 2011. In the third wave, renewed risk aversion resulted in annual equivalent inflation of minus 2.4 percent in Dec 2011-Jan 2012. In the fourth wave, new carry trades resulted in annual equivalent inflation of 2.4 percent in Feb-Apr 2012. In the fifth wave, annual equivalent is minus 5.8 percent in May-Sep 2012. There are declining producer prices in China in Aug-Sep 2012 in contrast with increases worldwide. In a sixth wave, producer prices increased 0.2 percent in Oct 2012, which is equivalent to 2.4 percent in a year. In an eighth wave, annual equivalent inflation was minus 1.2 percent in Nov-Dec 2012. In the ninth wave, annual equivalent inflation in Jan-Mar 2013 is 1.6 percent.

Table IV-9, China, Month and 12-Month Rate of Change of Producer Price Index, ∆%

| 12-Month ∆% | Month ∆% | |

| Mar 2013 | -1.9 | 0.0 |

| Feb | -1.6 | 0.2 |

| Jan | -1.6 | 0.2 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Mar | 1.6 | |

| Dec 2012 | -1.9 | -0.1 |

| Nov | -2.2 | -0.1 |

| AE ∆% Nov-Dec | -1.2 | |

| Oct | -2.8 | 0.2 |

| AE ∆% Oct | 2.4 | |

| Sep | -3.6 | -0.1 |

| Aug | -3.5 | -0.5 |

| Jul | -2.9 | -0.8 |

| Jun | -2.1 | -0.7 |

| May | -1.4 | -0.4 |

| AE ∆% May-Sep | -5.8 | |

| Apr | -0.7 | 0.2 |

| Mar | -0.3 | 0.3 |

| Feb | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Apr | 2.4 | |

| Jan | 0.7 | -0.1 |

| Dec 2011 | 1.7 | -0.3 |

| AE ∆% Dec-Jan | -2.4 | |

| Nov | 2.7 | -0.7 |

| Oct | 5.0 | -0.7 |

| Sep | 6.5 | 0.0 |

| Aug | 7.3 | 0.1 |

| Jul | 7.5 | 0.0 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | -3.1 | |

| Jun | 7.1 | 0.0 |

| May | 6.8 | 0.3 |

| Apr | 6.8 | 0.5 |

| Mar | 7.3 | 0.6 |

| Feb | 7.2 | 0.8 |

| Jan | 6.6 | 0.9 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Jun | 6.4 | |

| Dec 2010 | 5.9 | 0.7 |

AE: Annual Equivalent

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/

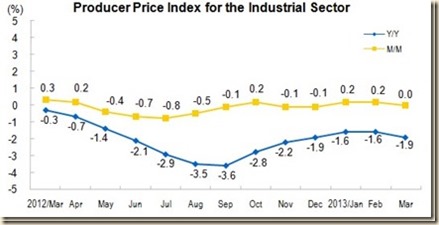

Chart IV-9 of the National Bureau of Statistics of China provides monthly and 12-month rates of inflation of the price indexes for the industrial sector. Negative monthly rates in Oct, Nov, Dec 2011, Jan, Mar, Apr, May, Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep, Nov and Dec 2012 pulled down the 12-month rates to 5.0 percent in Oct 2011, 2.7 percent in Nov, 1.7 percent in Dec, 0.7 percent in Jan 2012, 0.0 percent in Feb, minus 0.3 percent in Mar, minus 0.7 percent in Apr, minus 1.4 percent in May, 2.1 in Jun, minus 2.9 percent in Jul, minus 3.5 percent in Aug, minus 3.6 percent in Sep. The increase of 0.2 percent in Oct 2012 pulled up the 12-month rate to minus 2.8 percent and the rate eased to minus 2.2 percent in Nov 2012 and minus 1.9 percent in Dec 2012. Increases of 0.2 percent in Jan and Feb 2013 pulled the 12-month rate to minus 1.6 percent while no change in Mar 2013 brought down the 12-month rate to minus 1.9 percent.

Chart IV-9, China, Producer Prices for the Industrial Sector Month and 12 months ∆%

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/

Chart IV-10 of the National Bureau of Statistics of China provides monthly and 12-month inflation of the purchaser product indices for the industrial sector. Decreasing monthly inflation with four successive contractions from Oct 2011 to Jan 2012 and May-Aug 2012 pulled down the 12-month rate to minus 4.1 percent in Aug and Sep. Consecutive increases of 0.1 percent in Sep and Oct 2012 raised the 12-month rate to minus 3.3 percent in Oct 2012. The rate eased to minus 2.8 in Nov 2012 with decrease of 0.2 percent in Nov 2012 and minus 2.4 percent in Dec 2012 with monthly decrease of 0.1 percent. Increase of 0.3 percent in Jan 2013 and 0.2 in Feb 2013 pulled the 12-month rate to minus 1.9 percent. Decrease of prices of 0.1 percent in Mar 2013 brought down the 12-month rate to minus 2.0 percent.

Chart IV-10, China, Purchaser Product Indices for Industrial Sector

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

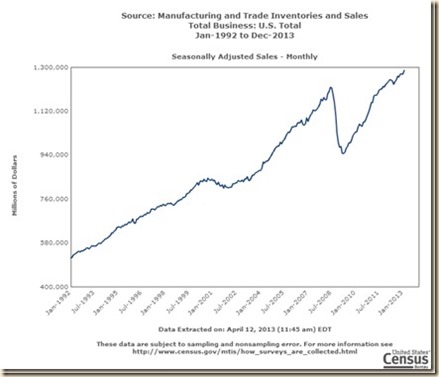

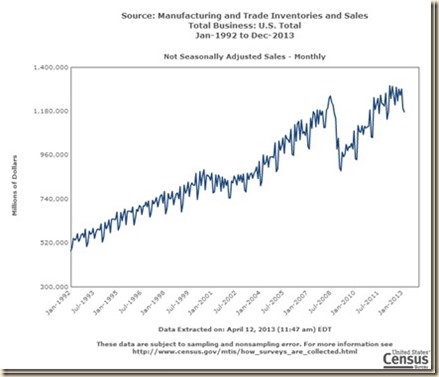

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/