Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011

Executive Summary

I Monetary Policy of Prosperity without Inflation

IA Prosperity and Inflation

IA1 Theory and Policy of Central Banking

IA2 US Inflation

IB Appendix Great Inflation and Unemployment Analysis

IB1 “New Economics” and the Great Inflation

IB2 Counterfactual with Current Science

IB3 Policy Rule and Politics

IB4 Supply Shocks

IB5 Conclusion

II World Financial Turbulence

III Global Inflation

IV World Economic Slowdown

IVA United States

IVB Japan

IVC China

IVD Euro Area

IVE Germany

IVF France

IVG Italy

IVH United Kingdom

V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VI Economic Indicators

VII Interest Rates

VII Conclusion

References

Appendix I The Great Inflation

Executive Summary

Short-term indicators of economies accounting for some three-quarters of world output are followed in this blog. The purchasing managers’ indexes are more current and integrated providing the best available world view. Data for the United States released in the week of Oct 21 are more encouraging. There are five conclusions based on the overall information.

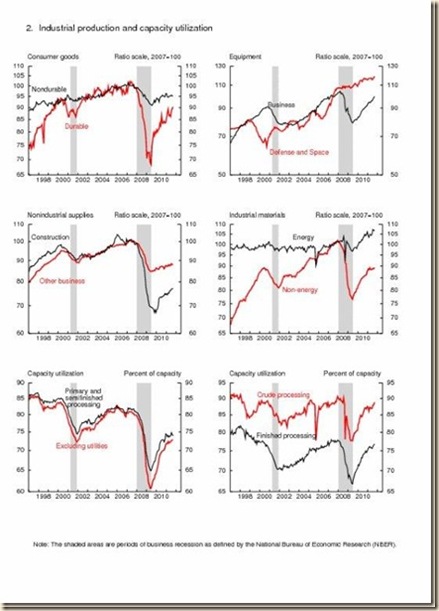

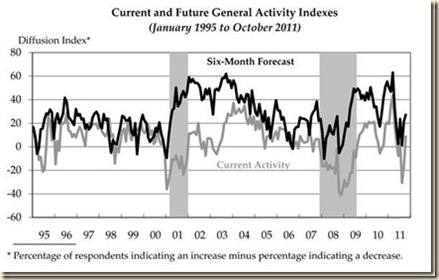

1. Recession. There appears to be improvement in output data globally in Jul, Aug and now also Sep. There is growing consensus that the world economy may not fall in recession but with higher doubts on Europe that manages a sovereign risk crisis with tough financial and political restrictions. Resolution of the European sovereign debt crisis would significantly improve the outlook for the world economy. Naturally, slower growth brings economies closer to contraction. Data for the US on industrial production confirm growth in Sep. The index of US industrial production of the Federal Reserve System finds growth of total industry of 0.2 percent in Sep and 3.2 percent in 12 months. Manufacturing rose 0.4 percent in Sep, 3.9 percent in the 12 months ending Sep and expanded in the quarter Jul-Sep at the annual equivalent rate of 5.7 percent. The Business Outlook Index of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia jumped from contraction level of minus 17.5 in Sep to positive 9.7 in Oct. New Orders rose from minus 11.3 in Sep to 7.9 in Oct.

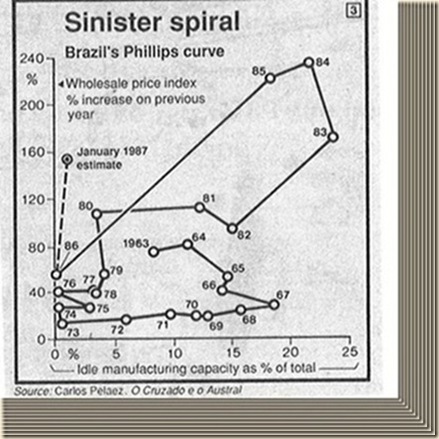

2. Inflation. There is evidence of moderation of inflation in recent monthly data. Concern with 12 months is because of wage increases. In a return of risk appetite with zero interest rates, commodity prices would soar again, raising world inflation. There is a good characterization that central banks attempt to inflate the economy in a negatively-sloping short-term Phillips curve that may prove yet another academic myth already disproved by the increase in interest rates by the Fed in 1981. The contributions of Thomas J. Sargent (1982, 1999) are quite relevant. Inflation has accelerated in annual equivalent quarterly rates in the US both for the consumer price index and the producer price index.

3. Labor Markets. Advanced economies continue to be plagued by fractured labor markets without improving perspectives.

4. Output Growth. The world economy and especially advanced economies are struggling with low rates of growth. Advanced economies have accumulated substantial imbalances that may restrict future growth but at some point expectations of inevitable consolidation by taxation and increases in interest rates to end unparalleled accommodation may reduce growth rates

5. Financial Turbulence. There will continue to be sharp fluctuations in valuations of risk financial assets. In recent weeks, volumes have thinned in various financial markets with the possibility of sharper fluctuations by professionals accustomed to reversing exposures to realize profits. This is an essential function of price discovery. European sovereign risks and increasingly the electoral agenda in the US will continue causing turbulence in financial markets

There have been three waves of consumer price inflation in the US in 2011. The first wave occurred in Jan-Apr and was caused by the carry trade of commodity prices, food and energy, induced by unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates. Cheap money at zero opportunity cost was channeled into financial risk assets, causing increases in commodity prices. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all-items CPI in Jan-Apr was 7.5 percent and the CPI excluding food and energy increased at annual equivalent rate of 2.8 percent. The second wave occurred during the collapse of the carry trade from zero interest rates to exposures in commodity futures as a result of risk aversion in financial markets created by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all items CPI dropped to 2.0 percent but the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy increased to 3.3 percent. The third wave occurred in the form of increase of the all items annual equivalent rate to 4.9 percent in Jul-Sep with the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy dropping to 2.0 percent. The conclusion is that inflation accelerates and decelerates in unpredictable fashion that turns symmetric inflation targets in a source of destabilizing shocks to the financial system and eventually the overall economy.

Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and large-scale purchases of long-term securities for the balance sheet of the central bank is proposed to prevent deflation. The data of CPI inflation of all goods and CPI inflation excluding food and energy for the past six decades show only one negative change by 0.4 percent in the CPI all goods annual index in 2009 but not one year of negative annual yearly change in the CPI excluding food and energy annual inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/world-financial-turbulence-global.html). Zero interest rates and quantitative easing are designed to lower costs of borrowing for investment and consumption, increase stock market valuations and devalue the dollar. In practice, the carry trade is from zero interest rates to a large variety of risk financial assets including commodities. Resulting food and energy price inflation squeezes family budgets and deteriorates the terms of trade with negative effects on aggregate demand and employment. Excessive valuations of risk financial assets eventually result in crashes of financial markets with possible adverse effects on economic activity and employment.

Producer price inflation history in the past five decades does not provide evidence of deflation. The finished core PPI does not register even one single year of decline. The headline PPI experienced only six isolated cases of decline (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/world-financial-turbulence-global.html):

-0.3 percent in 1963,

-1.4 percent in 1986,

-0.8 percent in 1986,

-0.8 percent in 1998,

-1.3 percent in 2001

-2.6 percent in 2009.

Deflation should show persistent cases of decline of prices and not isolated events. Fear of deflation in the US has caused a distraction of monetary policy. Symmetric inflation targets around 2 percent in the presence of multiple lags in effect of monetary policy and imperfect knowledge and forecasting are mostly unfeasible and likely to cause instability instead of desired price stability.

Chart ES1 provides the consumer price index NSA from 1960 to 2011. The dominating characteristic is the increase in slope during the Great Inflation from the middle of the 1960s through the 1970s. There is long-term inflation in the US and no evidence of deflation risks.

Chart ES1, US, Consumer Price Index, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart ES2 provides 12 month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 1960 to 2011. There are actually three waves of inflation in the second half of the 1960s, in the mid 1970s and again in the late 1970s. Inflation rates then stabilized in a range with only two episodes above 5 percent.

Chart ES2, US, Consumer Price Index, All Items, 12 Month Percentage Change 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart ES3 provides the consumer price index excluding food and energy from 1960 to 2011. There is long-term inflation in the US without episodes of deflation.

Chart ES3, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 1960-211

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart ES3 provides 12 months percentage changes of the consumer price index excluding food and energy from 1960 to 2011. Core inflation did exist during the Great Inflation and was conquered simultaneously with headline inflation.

Chart ES3, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The evident lack of deflation risks in the US economy supports reconsideration of unconventional monetary policy and the return to normalcy. Potential benefits of stimulating the economy are outweighed by the costs of distortions.

I Monetary Policy of Prosperity without Inflation. This section analyzes the objectives of current monetary policy of attaining prosperity while restraining inflation that has dominated policy making during the past decade. Prosperity is considered in the narrow sense of aggregate economic growth that maintains full employment (Hicks 1975). Inflation is considered as restraining inflation at what is now generally accepted as change of the consumer price index of two percent per year. Subsection IA Monetary Policy of Prosperity without Inflation considers the norms of policy in the light of the current reports on consumer and producer price inflation. A technical appendix, Subsection IB Appendix Great Inflation and Unemployment Analysis, provides more technical analysis of theory and empirical measurement that can be skipped by readers with less time for technical details. Appendix I The Great Inflation at the end of this comment provides further information.

IA Prosperity and Inflation. This section is divided into two subsections. The framework used currently in central banking is provided in subsection IA1 Theory and Policy of Central Banking. Historical inflation data and the current inflation reports of the US are analyzed in subsection IA2 US Inflation.

IA1 Theory and Policy of Central Banking. “Flexible inflation targeting” has dominated monetary policy during the past decade in several central banks (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009a), 99-116, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009b), 85-90). “Central bank doctrine and practice” has been reformulated by Chairman Bernanke (2011Oct18) in the light of the experience of the global recession that afflicted the US between IVQ2007 (fourth quarter 2007) and IIQ2009 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). “Doctrine” has much less precision and uncertainty of results than “science” as systematic pursuit of knowledge. Reflecting on the need to bridge academic knowledge with practical experience, Blinder (1997, 17) referred to a “science” of central banking:

“Having looked at monetary policy from both sides now, I can testify that central banking in practice is as much art as science. Nonetheless, while practicing this dark art, I always found the science quite useful. And I came to believe that the Federal Reserve and other central banks could profit from more disciplined and systematic thinking.

There has long been a symbiosis between practical central banking and academic research on monetary policy. Poole's analysis of the choice of the monetary instrument is only the most outstanding example. But while this symbiotic relationship continues, I believe that large potential gains from trade in ideas between practitioners and academics remain unexploited.

As a general matter, I firmly believe that monetary policymaking in the United States and other countries could and should become far more conceptual and less situational. This sounds a bit like saying that central banking should become "more academic"; but, as you will see in a moment, that is not what I mean. My experience at the Fed convinced me that central bankers are often so absorbed by the "trees" of the current economic situation that they lose sight of the macroeconomic "forest." They need to be constantly reminded of the latter. They need to specify their ultimate goals and their long-run plans to achieve them, however tentative those plans may be. And they need to internalize better the dynamic programming way of thinking”

A landmark synthesis of the “science of monetary policy” is provided by Clarida, Galí and Gertler (1999). The existence of such a science was also claimed much earlier by Heller (1966), Okun (1972) and Tobin (1970, 1980). The contention of the earlier claim was not very different that textbook economics provides policy tools to maintain continuously full employment of labor, capital and natural resources, or prosperity, while at the same time restraining inflation. The consensus or “neoclassical synthesis” is based on a relation in the “short term” known as the “augmented Phillips curve” that can be simplified in words as follows:

(current unemployment less natural unemployment) depends inversely on (current inflation less inflation expectations)

Or

(output gap) depends inversely on (inflation gap)

When the gap of actual output tightens relative to the maximum possible or potential output, inflation increases above normal or expected inflation. Inflation is determined by “slack” or unused potential in product and labor markets. Thus, inflation accelerates when the economy is moving toward full utilization of resources such as installed equipment, labor and natural resources. When the economy is growing slowly with less than full utilization of capacity and high unemployment, as currently, more equipment can be installed without increasing costs and more labor can be hired without increasing wages. The role of monetary policy is to lower interest rates such that lower financing costs of equipment and of consuming goods can increase aggregate investment and consumption that can raise output and employment but without increasing prices. Inflation would only accelerate when the economy moves toward full utilization of capacity and full employment of labor.

Central bank policy can be simplified to managing the short-term policy interest rate in accordance with the output gap and the inflation gap:

(Fed funds rate) depends on (output gap) and (inflation gap)

The central bank controls the fed funds rate or rate in overnight loans by banks of reserves deposited at the regional Federal Reserve Banks. This rate is the cost of lending an additional dollar for consumption and investment. A decrease in the fed funds rate lowers the cost of lending to banks that in turn lowers the rates charged to customers for loans to investors and consumers. The resulting increase in investment and consumption, that together make aggregate demand for goods and services in the economy, causes an increase in aggregate output, reducing the gap between actual and potential output and thus unemployment.

When slack in product and labor markets is reduced, inflation can accelerate. The central bank can then increase the fed funds rate. The increase in the cost of lending to banks causes an increase in the rates charged to investors and consumers with resulting decrease in consumption and investment that increases slack in product and labor markets. The increase in interest rates lowers inflation.

An important analysis of the Great Inflation of the 1960s and 1970s is the “inflation hills” of Blinder (1979, 1982) and Blinder and Rudd (2010). “Headline inflation” is the index of all items such as the consumer price index (CPI) all items. “Core inflation” is the index of all items excluding food and energy. “Inflation hills” are caused by “supply shocks,” which consist mostly of political events or events of nature that restrict supply of commodities, increasing their prices. An example of political events in the 1970s was the Iranian Revolution that caused spikes in oil prices and an example of events of nature is a frost in Florida that causes destruction of oranges and increases in orange juice prices. Aggregate demand determines underlying or core inflation in such a way that inflation hills collapse after the end of geopolitical and nature events. Thus, headline inflation converges toward core or actual inflation. The indicator of inflation for monetary policy is core inflation that predicts where headline inflation will be a year from now.

Monetary policy in the US between the second half of the 1960s and 1980 concentrated on minimizing the output gap. Research reviewed in IB Appendix Great Inflation and Unemployment Analysis explains the resulting highest inflation in a historical period in the US with high unemployment, known as stagflation, by three different arguments.

First, Inflation Surprise. The monetary authorities believed in the short-term tradeoff of inflation and unemployment. Deliberately, the monetary authorities implemented policies that would create an “inflation surprise” (Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983). The economy would reduce the output gap but at the expense of an inflation gap. The central bank created “stops and go” economic conditions: the economy expanded with inflation surprise and then was restrained when inflation increased to higher undesirable levels.

Second, Model Error. The monetary authorities did not have current methods of optimal control. Lack of current knowledge prevented management of the output and inflation gaps optimally (Clarida, Galí and Gertler 2000). Recently, Orphanides and Williams (2010) have provided econometric evidence that the policies of concentrating solely on the output gap while ignoring the inflation gap followed in the Great Inflation would have resulted in policy errors even if the authorities of the time had current central banking methods.

Third, Measurement Error. The monetary authorities relied on measurements of potential output that was higher, causing errors in ignoring inflation (Orphanides 2003, 2004). Recently, Orphanides and Williams (2010) have reconstructed the policy of the 1960s and 1970 with correct measurements of potential output, showing that there would have been inflation even with accurate input of potential output in monetary policy decisions.

An important strand of analysis of the Great Inflation is the consequence of coordination of monetary and fiscal policy, or what Sargent and Wallace (1981) have called “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic.” If the demand for base money depends on inflation expectations together with other assumptions, loser monetary policy can result in higher inflation now and also in the future. Base money consists of the monetary liabilities of the government, which are currency held by the public and reserves of banks deposited at the central bank. Sargent and Wallace (1973, 1046) show that if the demand for real cash balances depends on the expected rate of inflation, “the equilibrium value of the price level at the current moment is seen to depend on the (expected) path of the money supply from now until forever.” The anticipation of high rates of base money growth in the future may increase the rate of inflation now. Sargent and Wallace (1981) show that currently tight monetary policy may not be potent to even lower the current rate of inflation. If fiscal policy dominates monetary policy with a sequence of deficits, monetary policy has to adapt within the budget constraint that the government finances deficits with seigniorage or printing money and borrowing from the public by issuing Treasury securities. If the sequence of deficits is “too big for too long,” under the assumptions of the model, “the monetary authority can make money tighter now only by making it looser later” (Sargent and Wallace 1981, 7). In the analysis of the hyperinflations in Europe, Sargent (1982, 89-90) concludes:

“The essential measures that ended hyperinflations in each of Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Poland were, first, the creation of an independent central bank that was legally committed to refuse the government’s demand for additional unsecured credit and, second, a simultaneous alteration in the fiscal policy regime. These measures were interrelated and coordinated. They had the effect of binding the government to place its debt with private parties and foreign governments which would value that debt according to whether it was backed by sufficiently large prospective taxes relative to public expenditures. In each case that we have studied, once it became widely understood that the government would not rely on the central bank for its finance, the inflation terminated and the exchanges stabilized. The four incidents we have studied are akin to laboratory experiments in which the elemental forces that cause and can be used to stop inflation are easiest to spot. I believe that these incidents are full of lessons about our own, less drastic predicament with inflation, if only we interpret them correctly.”

Economics has been enriched by the pathbreaking contributions of Thomas J. Sargent and Christopher A. Sims (see Sims 1980, 1972). Their contributions have received momentous recognition (http://www.kva.se/en/pressroom/Press-releases-2011/The-Prize-in-Economic-Sciences-2011/):

“The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel for 2011 toThomas J. Sargent, New York University, New York, NY, USA, and Christopher A. Sims, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA,

“for their empirical research on cause and effect in the macroeconomy”.

Thomas Sargent has shown how structural macroeconometrics can be used to analyze permanent changes in economic policy. This method can be applied to study macroeconomic relationships when households and firms adjust their expectations concurrently with economic developments. Sargent has examined, for instance, the post-World War II era, when many countries initially tended to implement a high-inflation policy, but eventually introduced systematic changes in economic policy and reverted to a lower inflation rate.

Christopher Sims has developed a method based on so-called vector autoregression to analyze how the economy is affected by temporary changes in economic policy and other factors. Sims and other researchers have applied this method to examine, for instance, the effects of an increase in the interest rate set by a central bank. It usually takes one or two years for the inflation rate to decrease, whereas economic growth declines gradually already in the short run and does not revert to its normal development until after a couple of years.

Although Sargent and Sims carried out their research independently, their contributions are complementary in several ways. The laureates’ seminal work during the 1970s and 1980s has been adopted by both researchers and policymakers throughout the world. Today, the methods developed by Sargent and Sims are essential tools in macroeconomic analysis.”

The contributions of Sargent and Sims opened many avenues for research. This note originates in a personal experience. Pelaez and Suzigan (1981) provided the monetary statistics of Brazil yearly 1808-1851 and quarterly 1852-1971 (see Pelaez 1974, 1975, 1976a,b, 1977, 1979, Pelaez and Suzigan 1978, 1981). The Granger-Sims test of Sims (1972) was applied to these data in the effort to discover the correct specification of regressions of money, income and prices (see Pelaez and Suzigan 1978, 192-99; Pelaez 1979, 103-12). This is just one of many cases in which economists benefitted immensely in their research from the outstanding contributions of Sargent and Sims.

The current framework used in central banking is formulated by Bernanke (2011Oct18) as:

“During the two decades preceding the crisis, central bankers and academics achieved a substantial degree of consensus on the intellectual and institutional framework for monetary policy. This consensus policy framework was characterized by a strong commitment to medium-term price stability and a high degree of transparency about central banks' policy objectives and economic forecasts. The adoption of this approach helped central banks anchor longer-term inflation expectations, which in turn increased the effective scope of monetary policy to stabilize output and employment in the short run. This broad framework is often called flexible inflation targeting, as it combines commitment to a medium-run inflation objective with the flexibility to respond to economic shocks as needed to moderate deviations of output from its potential, or "full employment," level. The combination of short-run policy flexibility with the discipline imposed by the medium-term inflation target has also been characterized as a framework of "constrained discretion."”

There is an obvious “symmetric inflation target” by which monetary policy would reduce interest rates toward zero when core inflation measured by the core index of personal consumption expenditures (core PCE) falls below 2 percent and would increase interest rates when core inflation exceeds 2 percent. “Flexible targeting” also considers reduction of the output gap while there is slack in product and labor markets, which prevents acceleration of inflation. Because inflation is never in an infinitesimal open interval of (1.99, 2.00) and unemployment in an interval of (5.39, 5.40), the central bank is almost always engaged in active monetary policy.

In addition, the central bank engages in “unconventional monetary policy.” When deflation threatens, fed funds rates are reduced toward zero as has been the case since Dec 16, 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm). Forward guidance of maintaining fed funds rates at near zero until 2013 is another unconventional tool (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20110809a.htm). Unconventional monetary policy has also included quantitative easing, or the purchase of long-term securities to lower their yields with the objective of reducing the costs of borrowing for investment and consumption (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20101103a.htm). “Operation twist” repeats similar policy in 1961 of selling short-term securities to buy long-term securities with the objective of reducing borrowing costs for investment and consumption (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20110921a.htm). Monetary policy has also engaged in buying mortgage-backed securities to lower costs of mortgages with the objective of reducing borrowing costs of purchases of houses. These policies are analyzed in past comments of this blog (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/collapse-of-household-income-and-wealth.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/world-inflation-quantitative-easing.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/treasury-yields-valuation-of-risk.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/11/quantitative-easing-theory-evidence-and.html).

The central bank also engaged in policies of financial stability. The central bank provided 11 different liquidity facilities during the financial crisis (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009b), 157-62, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 224-7). Bernanke (2011Oct18) explains:

“Following a much older tradition of central banking, the crisis has forcefully reminded us that the responsibility of central banks to protect financial stability is at least as important as the responsibility to use monetary policy effectively in the pursuit of macroeconomic objectives.”

IA2 US Inflation. Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing has been inspired by fear of deflation (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-95). Key percentage average yearly rates of the US economy on growth and inflation are provided in Table 1 updated with release of new data. The choice of dates prevents the measurement of long-term potential economic growth because of two recessions from IQ2001 (Mar) to IVQ2001 (Nov) with decline of GDP of 0.4 percent and the drop in GDP of 5.1 percent in IVQ2007 (Dec) to IIQ2009 (June) (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html) followed with unusually low economic growth for an expansion phase after recession with the economy growing at the annual equivalent rate of 0.8 percent in the first half of 2011 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/10/us-growth-standstill-at-08-percent.html). Between 2000 and 2010, real GDP grew at the average rate of 1.6 percent per year, nominal GDP at 3.9 percent and the implicit deflator at 2.5 percent. The average rate of CPI inflation was 2.4 percent per year and 2.5 percent excluding food and energy. PPI inflation increased at 2.7 percent per year on average and at 1.6 percent excluding food and energy. There is also inflation in international trade. Import prices grew at 2.5 percent per year between 2000 and 2010 and 3.4 percent between 2000 and 2011. The commodity price shock is revealed by inflation of import prices of petroleum at 12.4 percent per year between 2000 and 2010 and at 14.8 percent between 2000 and 2011. The average growth rates of import prices excluding fuels are much lower at 1.7 percent for 2002 to 2010 and 2.1 percent for 2000 to 2011. Export prices rose at the average rate of 2.1 percent between 2000 and 2010 and at 2.7 percent in 2000 to 2011. What spared the US of sharper decade-long deterioration of the terms of trade, (export prices)/(import prices) was its diversification and competitiveness in agriculture. Agricultural export prices grew at the average yearly rate of 5.2 percent from 2000 to 2010 and at 6.6 percent from 2000 to 2011. US nonagricultural export prices rose at 1.8 percent per year in 2000 to 2010 and at 2.3 percent in 2000 to 2011. These dynamic growth rates are not similar to those for the economy of Japan where inflation was negative in seven of the 10 years in the 2000s.

Table 1, US, Average Growth Rates of Real and Nominal GDP, Consumer Price Index, Producer Price Index and Import and Export Prices, Percent per Year

| Real GDP | 2000-2010: 1.6% |

| Nominal GDP | 2000-2010: 3.9% |

| Implicit Price Deflator | 2000-2010: 2.5% |

| CPI | 2000-2010: 2.4% |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 2000-2010: 2.0% |

| PPI | 2000-2010: 2.7% |

| PPI ex Food and Energy | 2000-2010: 1.6% |

| Import Prices | 2000-2010: 2.5% |

| Import Prices of Petroleum and Petroleum Products | 2000-2010: 12.4% |

| Import Prices Excluding Fuels | 2002-2010: 1.7% |

| Export Prices | 2000-2010: 2.1% |

| Agricultural Export Prices | 2000-2010: 5.2% |

| Nonagricultural Export Prices | 2000-2010: 1.8% |

Note:rates for price indexes in the row beginning with “CPI” and ending in the row “Nonagricultural Export Prices” are for Sep 2000 to Sep 2010 and and for Sep 2010 to Sep 2011. Import prices excluding fuels are not available before 2002.

Sources:

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

http://www.bls.gov/mxp/data.htm http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and large-scale purchases of long-term securities for the balance sheet of the central bank is proposed to prevent deflation. The data of CPI inflation of all goods and CPI inflation excluding food and energy for the past six decades show only one negative change by 0.4 percent in the CPI all goods annual index in 2009 but not one year of negative annual yearly change in the CPI excluding food and energy annual inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/world-financial-turbulence-global.html). Zero interest rates and quantitative easing are designed to lower costs of borrowing for investment and consumption, increase stock market valuations and devalue the dollar. In practice, the carry trade is from zero interest rates to a large variety of risk financial assets including commodities. Resulting commodity price inflation squeezes family budgets and deteriorates the terms of trade with negative effects on aggregate demand and employment. Excessive valuations of risk financial assets eventually result in crashes of financial markets with possible adverse effects on economic activity and employment.

Producer price inflation history in the past five decades does not provide evidence of deflation. The finished core PPI does not register even one single year of decline. The headline PPI experienced only six isolated cases of decline (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/world-financial-turbulence-global.html):

-0.3 percent in 1963,

-1.4 percent in 1986,

-0.8 percent in 1986,

-0.8 percent in 1998,

-1.3 percent in 2001

-2.6 percent in 2009.

Deflation should show persistent cases of decline of prices and not isolated events. Fear of deflation in the US has caused a distraction of monetary policy. Symmetric inflation targets around 2 percent in the presence of multiple lags in effect of monetary policy and imperfect knowledge and forecasting are mostly unfeasible and likely to cause instability instead of desired price stability.

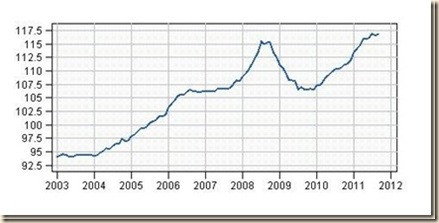

Chart 1 provides US nominal GDP from 1980 to 2010. The only major bump in the chart occurred in the recession of IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Tendency for deflation would be reflected in persistent bumps. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.5 percent cumulatively and fell 45.6 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is entirely misleading.

Chart 1, US, Nominal GDP 1980-2010

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart 2 provides US real GDP from 1980 to 2010. Persistent deflation threatening real economic activity would also be reflected in the series of long-term growth of GDP. There is no such behavior in Chart 3 except for periodic recessions in the US economy that have occurred throughout history.

Chart 2, US, Real GDP 1980-2010

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Deflation would also be in evidence in long-term series of prices in the form of bumps. The GDP implicit deflator series in Chart 3 from 1980 to 2010 shows rather dynamic behavior over time. The US economy is not plagued by deflation but by long-run inflation.

Chart 3, US, GDP Implicit Price Deflator 1980-2010

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The producer price index of the US from 1960 to 2011 in Chart 4 shows various periods of more rapid or less rapid inflation but no bumps. The major event is the decline in 2008 when risk aversion because of the global recession caused the collapse of oil prices from $148/barrel to less than $80/barrel with most other commodity prices also collapsing. The event had nothing in common with explanations of deflation but rather with the concentration of risk exposures in commodities after the decline of stock market indexes. Eventually, there was a flight to government securities because of the fears of insolvency of banks caused by statements supporting proposals for withdrawal of toxic assets from bank balance sheets in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), as explained by Cochrane and Zingales (2009).

Chart 4, US, Producer Price Index, Finished Goods, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Chart 5 provides 12 month percentage changes of the producer price index from 1960 to 2011. The distinguishing event in Chart 3 is the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The shape of the two-hump Bactrian camel of the 1970s resembles the double hump from 2007 to 2011.

Chart 5, US, Producer Price Index, Finished Goods, 12 Months Percentage Change, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The producer price index excluding food and energy from 1974, the first historical data of availability in the dataset of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), to 2011, shows similarly dynamic behavior as the overall index, as shown in Chart 6. There is no evidence of persistent deflation in the US PPI.

Chart 6, US Producer Price Index, Finished Goods Excluding Food and Energy, SA, 1974-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Chart 7 provides 12 months rates of change of the finished goods index excluding food and energy. The dominating characteristic is the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The double hump illustrates how inflation may appear to be subdued and then returns with strength.

Chart 7, US Producer Price Index, Finished Goods Excluding Food and Energy, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1974-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The producer price index of energy goods from 1974 to 2011 is provided in Chart 8. The first jump occurred during the Great Inflation of the 1970s analyzed in various comments of this blog (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html) and in Appendix I. There is relative stability of producer prices after 1986 with another jump and decline in the late 1990s into the early 2000s. The episode of commodity price increases during a global recession in 2008 could only have happened with interest rates dropping toward zero, which stimulated the carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in commodity futures. Commodity futures exposures were dropped in the flight to government securities after Sep 2008. Commodity future exposures were created again when risk aversion diminished around Mar 2011 after the finding that US bank balance sheets did not have the toxic assets that were mentioned in proposing TARP in Congress (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009). Fluctuations in commodity prices and other risk financial assets originate in carry trade when risk aversion ameliorates.

Chart 8, US, Producer Price Index, Finished Energy Goods, SA, 1974-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Chart 9 shows the 12 month percentage change of the producer price index of finished energy goods from 1975 to 2011. This index is only available after 1974 and captures only one of the humps of energy prices during the Great Inflation. Fluctuations in energy prices have occurred throughout history in the US but without provoking deflation. Two cases are the decline of oil prices in 2001 to 2002 that has been analyzed by Barsky and Kilian (2004) and the collapse of oil prices from over $140/barrel with shock of risk aversion to the carry trade in Sep 2008.

Chart 9, US, Producer Price Index, Finished Energy Goods, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1974-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Chart 10 provides the consumer price index NSA from 1960 to 2011. The dominating characteristic is the increase in slope during the Great Inflation from the middle of the 1960s through the 1970s. There is long-term inflation in the US and no evidence of deflation risks.

Chart 10, US, Consumer Price Index, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 11 provides 12 month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 1960 to 2011. There are actually three waves of inflation in the second half of the 1960s, in the mid 1970s and again in the late 1970s. Inflation rates then stabilized in a range with only two episodes above 5 percent.

Chart 11, US, Consumer Price Index, All Items, 12 Month Percentage Change 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 12 provides the consumer price index excluding food and energy from 1960 to 2011. There is long-term inflation in the US without episodes of deflation.

Chart 12, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 13 provides 12 months percentage changes of the consumer price index excluding food and energy from 1960 to 2011. Core inflation did exist during the Great Inflation and was conquered simultaneously with headline inflation. Sargent (1999) finds that inflation could return (see also Sargent 1983).

Chart 13, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1960-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The consumer price index of housing is provided in Chart 14. There was also acceleration during the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The index flattens after the global recession in IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Housing prices collapsed under the weight of construction of several times more housing than needed. Surplus housing originated in subsidies and artificially low interest rates in the shock of unconventional monetary policy in 2003 to 2004 in fear of deflation.

Chart 14, US, Consumer Price Index Housing, NSA, 1967-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 15 provides 12 months percentage changes of the housing CPI. The Great Inflation also had extremely high rates of housing inflation. Housing is considered as potential hedge of inflation.

Chart 15, US, Consumer Price Index, Housing, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1968-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Consumer price inflation has accelerated in recent months. Table 2 provides the 12 months and annual equivalent rate for the months of Jul to Sep of the CPI and major segments. CPI inflation in the 12 months ending in Sep reached 3.9 percent and the annual equivalent rate Jul-Sep was 4.9 percent. Excluding food and energy, CPI inflation was 2.0 percent. There is no deflation in the US economy that could justify further quantitative. Consumer food prices in the US have risen 4.7 percent in 12 months and 5.3 percent in annual equivalent in Jul-Sep. Monetary policies stimulating carry trades of commodities that increase prices of food constitute a highly regressive tax on lower income families for whom food is a major portion of the consumption basket. Energy prices returned with increase of 19.3 percent in 12 months and 26.8 percent in annual equivalent in Jul-Aug. For the lower income families, food and energy are a major part of the family budget. Inflation is not low or threatening deflation in annual equivalent in Jul-Sep in any of the categories in Table 2.

Table 2, US, Consumer Price Index Percentage Changes 12 months NSA and Annual Equivalent ∆%

| ∆% 12 Months Sep 2011/Sep | ∆% Annual Equivalent Jul-Sep 2011 SA | |

| CPI All Items | 3.9 | 4.9 |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Food | 4.7 | 5.3 |

| Food at Home | 6.3 | 7.4 |

| Food Away from Home | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Energy | 19.3 | 26.8 |

| Gasoline | 33.3 | 45.3 |

| Fuel Oil | 33.4 | -10.7 |

| New Vehicles | 3.6 | 0.0 |

| Used Cars and Trucks | 5.1 | 4.1 |

| Medical Care Commodities | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| Apparel | 3.5 | 4.8 |

| Services Less Energy Services | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Shelter | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| Transportation Services | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Medical Care Services | 2.8 | 3.3 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

The weights of the CPI, US city average, are shown in Table 3. Housing has a weight of 41.460 percent. The combined weight of housing and transportation is 58.768 percent or more than one half. The combined weight of housing, transportation and food and beverages is 73.56 percent of the US CPI.

Table 3, US, Relative Importance, 2007-2008 Weights, of Components in the Consumer Price Index, US City Average, Dec 2010

| All Items | 100.000 |

| Food and Beverages | 14.792 |

| Food | 13.742 |

| Food at home | 7.816 |

| Food away from home | 5.926 |

| Housing | 41.460 |

| Shelter | 31.955 |

| Rent of primary residence | 5.925 |

| Owners’ equivalent rent | 24.905 |

| Apparel | 3.601 |

| Transportation | 17.308 |

| Private Transportation | 16.082 |

| New vehicles | 3.513 |

| Used cars and trucks | 2.055 |

| Motor fuel | 5.079 |

| Gasoline | 4.865 |

| Medical Care | 6.627 |

| Medical care commodities | 1.633 |

| Medical care services | 4.994 |

| Recreation | 6.293 |

| Education and Communication | 6.421 |

| Other Goods and Services | 3.497 |

Source: ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiri2010.txt

Chart 16 provides the US consumer price index for housing from 2001 to 2011. Housing prices rose sharply during the decade until the bump of the global recession and are increasing again in 2011. The CPI excluding housing would likely show much higher inflation. Income left after paying for indispensable shelter has been compressed by the commodity carry trades resulting from unconventional monetary policy.

Chart 16, US, Consumer Price Index, Housing, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 17 provides 12 month percentage changes of the housing CPI. Percentage changes collapsed during the global recession but have been rising into positive territory in 2011.

Chart 17, US, Consumer Price Index, Housing, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

There have been three waves of consumer price inflation in the US in 2011 that are illustrated in Table 4. The first wave occurred in Jan-Apr and was caused by the carry trade of commodity prices induced by unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates. Cheap money at zero opportunity cost was channeled into financial risk assets, causing increases in commodity prices. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all-items CPI in Jan-Apr was 7.5 percent and the CPI excluding food and energy increased at annual equivalent rate of 2.8 percent. The second wave occurred during the collapse of the carry trade from zero interest rates to exposures in commodity futures as a result of risk aversion in financial markets created by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all items CPI dropped to 2.0 percent but the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy increased to 3.3 percent. The third wave occurred in the form of increase of the all items annual equivalent rate to 4.9 percent in Jul-Sep with the annual equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy dropping to 2.0 percent. The conclusion is that inflation accelerates and decelerates in unpredictable fashion that turns symmetric inflation targets in a source of destabilizing shocks to the financial system and eventually the overall economy.

Table 4, US, Headline and Core CPI Inflation Monthly SA and 12 Months NSA ∆%

| All Items SA Month | All Items NSA 12 month | Core SA | Core NSA | |

| Sep 2011 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Aug | 0.4 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| Jul | 0.5 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Sep | 4.9 | 2.0 | ||

| Jun | -0.2 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| May | 0.2 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 2.0 | 3.3 | ||

| Apr | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Mar | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Feb | 0.5 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Jan | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 7.5 | 2.8 | ||

| Dec 2010 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Nov | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Sep | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

| Aug | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Jun | -0.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| May | -0.1 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Apr | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Mar | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Feb | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jan | 0.1 | 2.6 | -0.1 | 1.6 |

Note: Core: excluding food and energy; AE: annual equivalent

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The behavior of the US consumer price index NSA from 2001 to 2011 is provided in Chart 18. Inflation in the US is very dynamic without deflation risks that would justify symmetric inflation targets. The hump in 2008 originated in the carry trade from interest rates dropping to zero into commodity futures. There is no other explanation for the increase of oil prices toward $140/barrel during the global recession. The unwinding of the carry trade with the TARP announcement of toxic assets in banks channeled cheap money into government obligations (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009).

Chart 18, US, Consumer Price Index, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 19 provides 12 month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 2001 to 2011. There was no deflation or threat of deflation from 2008 into 2009. Commodity prices collapsed during the panic of toxic assets in banks. When stress tests revealed US bank balance sheets in much stronger position, cheap money at zero opportunity cost exited government obligations and flowed into carry trades of risk financial assets. Increases in commodity prices drove again the all items CPI with interruptions during risk aversion originating in the sovereign debt crisis of Europe.

Chart 19, US, Consumer Price Index, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The trend of increase of the consumer price index excluding food and industry in Chart 20 does not reveal any threat of deflation that would justify symmetric inflation targets. There are mild oscillations in a neat upward trend.

Chart 20, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart 21 provides 12 month percentage change of the consumer price index excluding food and energy. Past-year rates of inflation fell toward 1 percent from 2001 into 2003 as a result of the recession and the decline of commodity prices beginning before the recession with declines of real oil prices. Near zero interest rates with fed funds at 1 percent between Jun 2003 and Jun 2004 stimulated carry trades of all types, including in buying homes with subprime mortgages in expectation that low interest rates forever would increase home prices permanently, creating the equity that would permit the conversion of subprime mortgages into creditworthy mortgages (Gorton 2009EFM; see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html). Inflation rose and then collapsed during the unwinding of carry trades and the housing debacle of the global recession. Carry trade into 2011 gave a new impulse to CPI inflation, all items and core. Symmetric inflation targets destabilize the economy by encouraging hunts for yields that inflate and deflate financial assets.

Chart 21, US, Consumer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The headline and core producer price index are in Table 5. The headline PPI increased 0.8 percent SA in Sep, raising the 12 month- rate NSA to 6.9 percent. The core PPI SA rose 0.2 percent in Sep and 2.5 percent in 12 months. Analysis of annual equivalent rates of change shows three different waves. In the first wave, the absence of risk aversion from the sovereign risk crisis in Europe, zero interest rates motivated the carry trade into commodity futures that caused the average equivalent rate of 17.3 percent in the headline PPI in Jan-Apr and 5.3 percent in the core PPI. In the second wave, commodity futures prices collapsed in May with the return of risk aversion originating in the sovereign risk crisis of Europe. The annual equivalent rate of headline PPI inflation collapsed to 0.8 percent in May-Jul but the core annual equivalent inflation rate was much higher at 3.3 percent. In the third wave, headline PPI inflation resuscitated with annual equivalent 4.1 percent in Jul-Sep and core PPI inflation was 2.8 percent. Core PPI inflation has been persistent throughout 2011 and has jumped from around 1 percent in the first four months of 2010 to 2.5 percent in 12 months and 2.8 percent in annual equivalent rate. It is impossible to forecast PPI inflation and its relation to CPI inflation. “Inflation surprise” by monetary policy could be proposed to climb along a downward sloping Phillips curve, resulting in higher inflation but lower unemployment (see Kydland and Prescott 1977, Barro and Gordon 1983 and past comments of this blog http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html). The architects of monetary policy would require superior inflation forecasting ability compared to forecasting naivety by everybody else. In practice, we are all naïve in forecasting inflation and other economic variables and events.

Table 5, US, Headline and Core PPI Inflation Monthly SA and 12 Months NSA ∆%

| Finished | Finished | Finished Core SA | Finished Core NSA | |

| Sep 2011 | 0.8 | 6.9 | 0.2 | 2.5 |

| Aug | 0.0 | 6.5 | 0.1 | 2.5 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 7.2 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| AE ∆% Jul-Sep | 4.1 | 2.8 | ||

| Jun | -0.1 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| May | 0.1 | 7.1 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 0.8 | 3.3 | ||

| Apr | 0.8 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 5.6 | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| Feb | 1.5 | 5.4 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 17.3 | 5.3 | ||

| Dec 2010 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Nov | 0.5 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Oct | 0.6 | 4.3 | -0.3 | 1.6 |

| Sep | 0.3 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Aug | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jul | 0.1 | 4.1 | 0.2 | 1.5 |

| Jun | -0.3 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| May | -0.2 | 5.1 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Apr | -0.1 | 5.4 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Feb | -0.4 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Jan | 1.1 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

Note: Core: excluding food and energy; AE: annual equivalent

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The US producer price index NSA from 2001 to 2011 is shown in Chart 22. There are two episodes of decline of the PPI during recessions in 2001 and in 2008. Barsky and Kilian (2004) consider the 2001 episode as one in which real oil prices were declining when recession began. Recession and the fall of commodity prices instead of generalized deflation explain the behavior of US inflation in 2008.

Chart 22, US, Producer Price Index, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

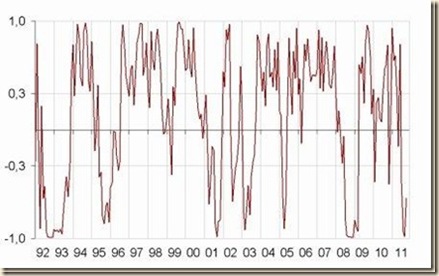

The 12 months rates of change of the PPI NSA from 2001 to 2011 are shown in Chart 23. It may be possible to forecast trends a few months in the future but turning points are almost impossible to anticipate especially when related to fluctuations of commodity prices in response to risk aversion. In a sense, monetary policy has been tied to behavior of the PPI in the negative 12 months rates in 2001 to 2003 and then again in 2009 to 2010. Monetary policy following deflation fears caused by commodity price fluctuations would introduce significant volatility and risks in financial markets and eventually in consumption and investment.

Chart 23, US, Producer Price Index, 12 Month Percentage Change NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The US PPI excluding food and energy from 2001 to 2011 is shown in Chart 24. There is here again a smooth trend of inflation instead of prolonged deflation as in Japan.

Chart 24, US, Producer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The 12 months rates of percentage change of the producer price index excluding food and energy are shown in Chart 25. Fluctuations replicate those in the headline PPI. There is an evident trend of increase of 12 months rates of core PPI inflation in 2011.

Chart 25, US, Producer Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12 Month Percentage Chance, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

The US producer price index of energy goods from 2001 to 2011 is in Chart 26. There is a clear upward trend with fluctuations that would not occur under persistent deflation.

Chart 26,US,Producer Price Index Energy Goods, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Chart 27 provides 12 months rates of change of the producer price index of energy goods from 2001 to 2011. The episode of declining prices of energy goods in 2001 to 2002 is related to the analysis of decline of real oil prices by Barsky and Kilian (2004). Interest rates dropping to zero during the global recession explain the rise of the PPI of energy goods toward 30 percent. Bouts of risk aversion with policy interest rates held close to zero explain the fluctuations in the 12 months rates of PPI of energy goods in the expansion phase of the economy. Symmetric inflation targets induce significant instability in inflation and interest rates with adverse effects on financial markets and the overall economy.

Chart 27, US, Producer Price Index Energy Goods, 12 Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

Table 6 provides 12 month percentage changes of the CPI all items, CPI core and CPI housing from 2001 to 2011. There is no evidence in these data supporting symmetric inflation targets that would only induce greater instability in inflation, interest rates and financial markets.

Table 6, CPI All Items, CPI Core and CPI Housing, 12 Months Rates of Change, NSA 2001-2011

| Sep | CPI All Items | CPI Core | CPI Housing |

| 2011 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| 2010 | 1.1 | 0.8 | -0.3 |

| 2009 | -1.3 | 1.5 | -0.5 |

| 2008 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| 2007 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| 2006 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 4.1 |

| 2005 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 |

| 2004 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| 2003 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| 2002 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| 2001 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

IB Great Inflation and Unemployment Analysis. Stagflation in the 1970s, or incidence of the highest inflation rates in peacetime history with high rates of unemployment, is a major issue of research. The strands of thoughts are covered in subsections: IB1 “New Economics” and the Great Inflation, IB2 Counterfactual with Current Science, IB3 Policy Rule and Politics, IB4 Supply Shocks and IB5 Conclusion.

IB1 “New Economics” and the Great Inflation. The New Economics and the Great Inflation. The “new economics,” or in the words of James Tobin (1980, 27), the “neoclassical synthesis,” dominated policy thought in the 1960s and 1970s, as vigorously exposed by Heller (1966), Okun (1970) and Tobin (1972), all of whom served in the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html). According to Heller (1975, 16), the major event breaking with the past was the 1964 tax cut. The target of policy shifted to attaining the economy’s “full employment potential,” following canonical Keynesian economics, while rejecting analysis of structural unemployment.

Heller (1975, 17) reflected on the policy approach of Heller (1966):

“On one hand, the high employment, limited-recession economy forged with our macroeconomic policy tools is indeed an inflation-prone economy—the formula for successful management of high-pressure prosperity is far more elusive than the formula for getting there. Yet on the other hand, success bred great expectations on the part of the public that economics could deliver prosperity without inflation and with ever-growing material gains in the bargain. The message got through that we had ‘harnessed the existing economics…to the purposes of prosperity, stability and growth,’ and that as to the role of the tax cut in breaking old molds of thinking, ‘nothing succeeds like success’(Heller [1966])”.

There is an even more detailed account of the gap management by fiscal/monetary policies away from cyclical adjustment to growth promotion (Burns 1969QFE, 279):

“The central doctrine of this school is that the stage of the business cycle has little relevance to sound economic policy; that policy should be growth-oriented instead of cycle-oriented; that the vital matter is whether a gap exists between actual and potential output; that fiscal deficits and monetary tools need to be used to promote expansion when a gap exists; and that the stimuli should be sufficient to close the gap—provided significant inflationary pressures are not whipped up in the process.”

The “consensus macroeconomic framework, vintage 1970” used by “managers of aggregate demand” in stabilization policies is interpreted by Tobin (1980, 23-5) in terms of five broad components.

(1) The key role in determining the rate of inflation is played by the nonagricultural business sector in which prices consist of marked-up labor costs. The standard model is the “augmented Phillips curve.”

(2) The only way in which aggregate monetary demand, or nominal income, affects prices, output, wages and employment is through tightness in labor and product markets. Combinations of fiscal and monetary policies that result in the same change in aggregate demand have the same impact on inflation and real economic activity.

(3) Okun’s law or empirical finding is that (Okun 1962):

“In the postwar period, on the average, each extra percentage point in the unemployment rate above four percent has been associated with about a three percent decrement in real GNP”

The statement is careful in expressing the empirical result on the basis of the structure estimated with data of 55 quarters from IIQ1947 to IVQ1960, resulting in the estimated relation (Okun 1962):

Y = 0.30 – 0.30X (1)

Where Y is the quarterly change in the unemployment rate expressed in percentage points and X is the quarterly percentage change of real GNP. If GNP is unchanged from one quarter to the next, X =0, trend increases in productivity and growth of the labor force result in an increase of the rate of unemployment by 0.3 percentage points. Unemployment is 0.3 point lower for each increment of one percent of GNP (0.30 x X = 0.3 x 1). An increase of one percentage point in unemployment is equivalent to decrease of GNP by 3.3 percent (1/0.3).

(4) Tighter markets of products and labor at high employment rates result in acceleration of inflation above those incorporated in inflation expectations and historical trends. Slack in product and labor market causes deceleration of inflation but at a slower rate. The utilization of resources and market tightness at the natural rate of unemployment of Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968) does not cause upward or downward pressure of wages and prices relative to expected paths. The consensus accepted a nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) but with divergence on whether it coincided with equilibrium or optimum employment.

(5) There was no widespread consensus on the instruments of demand management.

Tobin (1980, 19) explained more accurately (see also Tobin 1980AA and Lucas 1981):

“Higher inflation, higher unemployment-the relentless combination frustrated policymakers, forecasters, and theorists throughout the decade. The disarray in diagnosing stagflation and prescribing a cure makes any appraisal of the theory and practice of macroeconomic stabilization as of 1980 a foolhardy venture.”

There are three interpretations of the role of monetary policy in causing the Great Inflation and Unemployment: (1) inflation surprise, (2) inadvertent policy mistake; and (3) imperfect information (for ample discussion see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html).

(1) Inflation Surprise. The analysis by Kydland and Prescott (1977, 447-80, equation 5) uses the “expectation augmented” Phillips curve with the natural rate of unemployment of Friedman (1968) and Phelps (1968), which in the notation of Barro and Gordon (1983, 592, equation 1) is:

Ut = Unt – α(πt – πe) α > 0 (2)

Where Ut is the rate of unemployment at current time t, Unt is the natural rate of unemployment, πt is the current rate of inflation and πe is the expected rate of inflation by economic agents based on current information. Equation (2) expresses unemployment net of the natural rate of unemployment as a decreasing function of the gap between actual and expected rates of inflation. Equation (2) is used by Barro and Gordon (1983) in showing the temptation of the policymaker to create “inflation surprises” by pursuing an inflation rate that is higher than that expected by economic agents which lowers the difference between the actual and natural unemployment rate by the term – α(πt – πe).

(2) The baseline monetary policy rule considered by Clarida, Galí and Gertler (2000) (CGG) is a simple linear equation:

r*t = r* + β(inflation gap) + γ(output gap) (3)

Where r*t is the Fed’s target rate for the fed funds rate in period t, r* is the desired nominal rate corresponding to both inflation and output being at their target levels (CGG 2000, 150), (inflation gap) is the deviation of actual inflation from target inflation and (output gap) is the percentage difference between actual GDP and its target. The rule is forward looking because the two gaps are relative to future desired levels. A second monetary rule is on the implied relation for the real rate of interest target:

rr*t = rr* + (β -1)(inflation gap) + γ(output gap) (4)

Where rr*t is the ex ante real rate target and rr* = r* - π* is the long-run equilibrium real rate. Equation (4) shows that the response of policy to the inflation gap depends on whether β is greater or less than one and the response to the output gap on whether γ is positive or negative. The data reveal that the Fed reacted weakly to expectations of inflation by allowing declines in real rates of interest or raising nominal interest but not by enough to increase real interest rates. That is, policy neglected control of the inflation gap and focused instead on the output gap.

(3) Orphanides (2003, 2004) emphasizes the erroneous measurement of potential output, and a consequence of the output gap in equation (4), which misled the regulators in pursuing an “activist” policy of trying to prevent the output gap from increasing when it was decreasing. The policy to prevent the erroneously measured output gap from increasing was lowering interest rates but the actual gap was actually tightening and inflation control required higher interest rates.

IB2 Counterfactual with Current Science. The dual mandate of the Fed consists of “conducting the nation's monetary policy by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm). In practice, the Fed has the challenging task of attaining two often conflicting targets: (1) reducing the gap of actual relative to potential output while simultaneously (2) controlling inflation at the target of 2 percent. Conventional monetary policy has one instrument, the fed funds rate, with which the Fed attempts to influence the current short-term interest rates and the term-structure of interest rates, which consists of the rates from one period in the future toward another future period, as for example, the rate at six months from now for investment six months forward or one year from now. Unconventional monetary policy consists of large-scale purchases of long-term securities with the objective of lowering yields on long-term securities that are closely related to borrowing costs for investment and consumption of durable goods.

Empirical economics typically faces counterfactuals. A counterfactual consists of using economic theory and measurement in evaluating what would have been the level and time path of critical economic variables if events and/or policies would have been different. Counterfactuals face not only tough hurdles of choice of appropriate theory in analyzing the issue in question but also availability of relevant data and measurement methods. Economic observations consist of data with mixed effects of what actually happened. Resolution of the counterfactual would require unobserved data of what would have happened under different events and/or policies.

The Great Inflation and Unemployment suggests two critical counterfactuals.

First, there is the counterfactual of what would have happened if policy during the early phase of creating the Great Inflation would have been similar to recent and current monetary policy. DeLong (1997) finds the onset of the Great Inflation in the 1960s. Table 7 shows the section of Table I1 in Appendix I The Great Inflation for the period 1960 to 1970. A counterfactual of the 1970s immediately rises out of Table 7, which consists of simulating current monetary and fiscal policies in doses much more aggressive than in the 1960s and 1970s proposed as a true rose garden without thorns (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html). What would have been the Great Inflation and Unemployment if the Federal Reserve would have lowered interest rates to zero in 1961, in fear of deflation because of 0.7 percent CPI inflation, and purchased the equivalent of 30 percent of the Treasury debt in long-term securities, subsequently engaging in quantitative easing II in 1964 after CPI inflation of 1.0 percent? The counterfactual would not be complete without including the unknown path of the US debt, tax and interest rate increases to exit from unsustainable debt and the largest monetary accommodation in US history.

Table 7, US Annual Rate of Growth of GDP and CPI and Unemployment Rate 1960-1967

| ∆% GDP | ∆% CPI | UNE | |

| 1960 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 6.6 |

| 1961 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 6.0 |

| 1962 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 5.5 |

| 1963 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 5.5 |

| 1964 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| 1965 | 6.4 | 1.9 | 4.0 |

| 1966 | 6.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| 1967 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

Note: GDP: Gross Domestic Product; CPI: consumer price index; UNE: rate of unemployment; CPI and UNE are at year end instead of average to obtain a complete series

Source: ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiai.txt

http://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpseea01.htm

http://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet

Second, economists believe that their knowledge of monetary policy has evolved into a more accurate science of optimal control. Orphanides and Williams (2010) pose and analyze the critically-important counterfactual of what would have happened if the Fed in the 1960s had the current science of central banking, availability in real time of correctly measured output gaps and the natural rate of unemployment and more balanced policy of inflation control instead of nearly exclusive emphasis on output gap reduction. The understanding of the Great Inflation has been enriched by their definition of the counterfactual issue and its importance, analysis and empirical method.

The counterfactual issue searched by Orphanides and Williams (2010, 1) is: “what monetary policy framework, if adopted by the Federal Reserve, would have avoided the Great Inflation of the 1960s and 1970s?” The structural model used by Orphanides and Williams (2010, 15-6) consists of two equations to model the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. The unemployment rate equation is:

ut = ϕuuet+1 + (1- ϕu)ut-1 + αu(iet – πet+1 – r*) + vt (5)

vt = ρvvt-1 + ev,t with ev ~ N(0, σ²ev) (6)

Equation (5) expresses the current rate of unemployment, ut, by means of three terms: (a) the effect the rate of unemployment expected to prevail in the next period, ϕuuet+1; (b) the effect of the unemployment rate in the past period, (1- ϕu)ut-1; and (c) term αu(iet – πet+1 – r*) which is the difference between the expected nominal short-term interest rate, iet, and the rate of inflation expected in the next period, πet+1, or expected ex-ante real rate of interest ret, and the natural rate of interest, that is (iet - πet+1 - r*) = ret - r*.

Orphanides and Williams (2010, 16) use a Phillips equation following a New Keynesian approach with indexation:

πt = ϕππet+1 + (1-ϕπ)πt-1 + απ(ut – u*t) + eπ,t

with eπ ~ N(0, σ²eπ) (7)

The Phillips curve in equation (7) expresses the current rate of inflation, πt, by three effects: (a) the influence of the rate of inflation expected to prevail in next period t+1, or effect ϕππet+1; (b) indexation that is captured by an effect of inflation in the prior period (1-ϕπ)πt-1; and (c) an effect of the difference between the actual rate of unemployment, ut, and the natural rate of unemployment, u*t, captured by the term απ(ut – u*t).

Optimal control (OC) policy consists in the central bank choosing the policy instrument to minimize the central bank’s loss function subject to the constraints of the central bank’s model (Orphanides and Williams 2010, 19; see Orphanides and Williams 2008, 2009; Bean 2003; Bean et al 2010; Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 110-6). The OC policy rule is obtained by assuming the central bank knows all parameters and economic agents decide on rational expectations. The loss function used by Orphanides and Williams (2010) is:

ℓ = Var (π -2) + λVar(u – un) + γVar(∆(i)) (8)

The central bank minimizes the variance of the inflation rate, π, less the inflation target of 2 percent, Var (π -2), plus the variance of the difference between the actual unemployment rate, u, less the natural rate of unemployment, un, plus the variance of the first difference of the nominal interest rate, (∆(i), or γVar(∆(i)). The emphasis on reduction of the output gap can be captured by alternative values of the parameter λ in equation (8) such as 16, 4 and 1.

The narrative of policy during the 1960s and 1970s by Orphanides and Williams (2010, 31) leads them to conclude that:

“Our narrative account of the Great Inflation squarely attributes the policy failures on mistakes consistent with what was viewed by many to be the latest advances in macroeconomics as embodied in the New Economics. The fine-tuning approach to monetary policy, with its emphasis on stabilizing the level of real activity, might have succeeded if policy makers had possessed accurate real-time assessments of the natural rate of unemployment. In the event, they did not and they failed to account for their imperfect information regarding the economy’s potential and the effects of these misperceptions on the evolution of expectations and inflation. Price and economic stability were only restored after the Federal Reserve, under Chairman Volcker, refocused policy on establishing and maintaining price stability.”

The quantitative research shows that modern OC policy would not have performed much better if the Fed had misperceptions of the natural rate of unemployment, resulting in failure to anchor inflation expectations that would have generated volatile inflation. OC policy would have been successful only with moderate weight on output gap stabilizing with the best results obtained with almost all weight on price stabilization.

IB3 Policy Rule and Politics. The objective of Levin and Taylor (2009) is to reveal the primary cause of the persistence of inflation drift during the Great Inflation by focusing on the path of inflationary expectations to model monetary policy from 1965 to 1980. They derive three stylized facts by use of measurements of inflation expectations. (1) Inflation began in the mid 1960 while it had been contained since the late 1950s at around 1 percent but inflation expectations accelerate beginning in 1965. (2) Long-term inflation expectations stabilized at a high level in the first half of the 1970s but catapulted toward the end of the decade. (3) Long-run inflation expectations only began to decline at the end of 1980. The central bank reaction function analyzed by Taylor (1993, 202, equation (1)) on the basis of prior research is:

r = p +0.5y + 0.5(p-2) + 2 (9)

In equation (9), the federal funds rate, r, is expressed in terms of the rate of inflation over the previous four quarters, the percentage output gap, y, defined as 100(Y-Y*)/Y*, where Y is actual GDP, Y* is trend real GDP (2.2 percent from IQ1984 to IIIQ1992), and the deviation of inflation from the target of 2 percent, 0.5(p-2). The Taylor policy rule in equation (9) triggers an increase in the fed funds rate when inflation exceeds 2 percent or when GDP exceeds trend GDP. If GDP is equal to target, y = 0, and inflation is also equal to target, p = 2, then the real rate of interest as measured by prior inflation, r-p, equal 2 percent. The fed funds rate calculated with this simple policy rule fits remarkably well the actual fed funds rate in 1987-1992 (Taylor 1993, 204, Figure 1).

The simple rule is restated by Levin and Taylor (2010, 16, equation (1)) to account for discrete shifts in the intercept: