Collapse of Household Income and Wealth, 46 Million in Poverty and 50 Million without Health Insurance and “Let’s Twist Again” Monetary Policy

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011

Executive Summary

I Collapse of Household Income and Wealth, 46 Million in Poverty and 50 Million without Health Insurance

II “Let’s Twist Again” Monetary Policy

IIA Appendix: Analysis, Measurement and Evaluation of Operation Twist and Quantitative Easing

III World Financial Turbulence

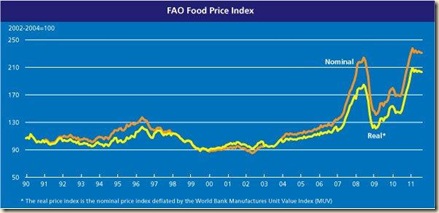

IV Global Inflation

IVA US Inflation

IVB Inflation in the Rest of the World

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Executive Summary

Newly released data by the US Census Bureau on income, poverty and health insurance (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011) and the flow of funds report of the Federal Reserve System for IIQ2011 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf) are summarized in Table ES 1. These reports depict 2010 household income of the US in constant 2010 dollars regressing to the level of 1996 and wealth of households and nonprofit organizations of the US in IIQ2011 falling $5.8 trillion below the level of 2007. The number of people in poverty in the US in 2010 is 46.180 million, equivalent to 15.1 percent of the population, which is the same as in 1993 and higher or equal than any percentage since 17.3 percent in 1965. The number of people without health insurance in 2010 is 49.904 million, which is 16.3 percent of the population. Although the economy recovered throughout 2010, income, wealth, poverty and lack of health insurance deteriorated. Increasing poverty and lack of health insurance suggest strengthening the social and health safety. Evidence provided in the text below shows that part of the explanation of the dramatically poor socio-economic indicators of the US could be explained by the sharp economic contraction from IV2007 to IIQ2009 but part originates in the worst recovery in a cyclical expansion during the postwar period.

Table ES 1, Summary of Social and Economic Indicators

| People in Poverty | 46.180 million 15.1% of population Among three highest since 1966 |

| People without Health Insurance | 49.985 million 16.1% of population |

| Median Household Income | $49,445 Worst since 1996 |

| People in Job Stress | 29.9 million unemployed or underemployed |

| Household Loss of Net Worth | -$5.8 trillion since 2007 |

| Household Loss of Real Estate | -$5.1 trillion since 2007 |

| Household Loss of Assets | -$6.3 trillion since 2007 |

Sources: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith (2011)

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics

The term “operation twist” grew out of the dance “twist” popularized by successful musical performer Chubby Chekker (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWaJ0s0-E1o). Financial markets are widely anticipating the return of Chubby Chekker’s “twisting time” or “let’s twist again” monetary policy perhaps even during the two-day meeting of the FOMC scheduled for Sep 20 to Sep 21 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm#9662).

The limited effects of operation twist were analyzed by Modigliani and Stuch (1966, 1967) with empirical estimation methods of their time in the 1960s. Swanson (2011Mar) provides analysis and measurement using current state of the art estimation methods.

Swanson (2011Mar) analyzes the policy mechanics of operation twist. President Kennedy faced two policy challenges after assuming office in Jan 1961: (1) international financial funds flowed in pursuit of higher short-term interest rates in Europe relative to those in the US that were restricted by prohibition of payment of interest on demand deposits and ceilings of interest on time deposits as provided by the Banking Act of 1933 and implemented by Regulation Q (for Regulation Q see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 74-5); and (2) the US was recovering from strong recession that lasted from IIQ1960 (Apr) to IQ1961 (Feb) (http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html). The objective of operation twist was maintaining stable or increasing short-term interest rates to prevent financial funds from flowing away from the US into Europe while simultaneously reducing long-term interest rates to stimulate investment and consumption, or aggregate demand. President Kennedy announced coordination of Treasury and FOMC policy as follows:

1. Treasury. The US Treasury would increase the issuance of short term securities while at the same time reduce the issuance of long-term securities. The desired effects of this policy would be in two forms:

i. The increase in the issuance of short-term Treasury securities would displace the supply curve of short-term securities downward and to the right. Assuming stable demand, the price of short-term Treasury securities would fall, which is equivalent to an increase in short-term interest rates that would prevent net outflows of capital from the US. There is a critical assumption here that capital flows among nations are determined by short-term interest rate differentials

ii. The reduction in the supply of long-term Treasury securities would cause displacement of the supply curve upward and to the left. Assuming stable demand, the price of long-term securities increases, which is equivalent to reducing yields of long-term securities

2. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC would decide to sell short-term securities and buy long-term securities with the following desired effects:

i. The sale of short-term Treasury securities could displace the supply curve downwardly and to the right. Assuming stable demand, the price of short-term Treasury securities would fall, which is equivalent to an increase in short-term rates of Treasury securities designed to prevent net outflows of international capital from the US

ii. The purchase of long-term Treasury securities would displace demand for long-term Treasury securities upward and to the right. The price of long-term Treasury securities would increase, which is equivalent to a reduction of yields of long-term Treasury securities

There is another operational factor of the “let’s twist again” monetary policy. Swanson (2011Mar) also reminds that lowering long-term yields in a new twist of the yield curve does not require increasing short-term rates as in the part of operation twist policy designed to prevent net capital outflows of the US. The desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York can continue to implement the target of fed funds rate of 0 to ¼ percent.

The crucial issue here is if lowering the yields of long-term Treasury securities would have any impact on investment and consumption or aggregate demand. The decline of long-term yields of Treasury securities would have to cause decline of yields of asset-backed securities used to securitize loans for investment by firms and purchase of durable goods by consumers. The decline in costs of investment and consumption of durable goods would ultimately have to result in higher investment and consumption.

I Collapse of Household Income and Wealth, 46 Million in Poverty and 50 Million without Health Insurance. The objective of this section is to analyze newly released data by the US Census Bureau on income, poverty and health insurance (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011) and the flow of funds report of the Federal Reserve System for IIQ2011 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf). These reports depict 2010 household income of the US in constant 2010 dollars regressing to the level of 1996 and wealth of households and nonprofit organizations of the US in IIQ2011 falling $5.8 trillion below the level of 2007. The number of people in poverty in the US in 2010 is 46.180 million, equivalent to 15.1 percent of the population, which is the same as in 1993 and higher than any percentage since 17.3 percent in 1965. The number of people without health insurance in 2010 is 49.904 million, which is 16.3 percent of the population. Although the economy recovered throughout 2010, income, wealth, poverty and lack of health insurance deteriorated. Increasing poverty and lack of health insurance pose urgent strengthening of the social and health safety net both on the basis of ethical considerations and on the economic need to increase labor input and maintain health of the stock of human capital. The final part of this section shows that part of the explanation of the dramatically poor socio-economic indicators of the US could be explained by the sharp economic contraction from IV2007 to IIQ2009 but part originates in the worst recovery in a cyclical expansion during the postwar period.

The report of the US Bureau of the Census on Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010 provides highly valuable socio-economic information and analysis (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011). Table 1 provides years of high percentage of people below poverty in the US. Data for 2006 to 2009 are included to provide a framework of reference for the current deterioration. The series has two high points of 15.1 percent of the population in poverty in 2010 and 1993 exceeded only by 15.2 percent in 1983. The prior high numbers of poverty are found in 1960 to 1965 with 17.3 percent in 1965 and higher numbers going to 22.4 percent in 1959. The number of people in poverty in the US in 2010 was 46.180 million, which has increased by 9.720 million from 36.460 million in 2006. The fractured job market with 29.6 million unemployed or underemployed because they cannot find full-time jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/global-growth-standstill-recession.html) and decline of hiring by 17 million (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/financial-turbulence-wriston-doctrine.html) prevents exit from poverty. Inflation-adjusted average weekly wages are declining throughout 2011.

Table 1, US, Historical High Percentage of People below Poverty, Thousands and Percent

| Total Population | Number Below Poverty | Percent Below Poverty | |

| 2010 | 305,688 | 46,180 | 15.1 |

| 2009 | 303,820 | 43,569 | 14.3 |

| 1993 | 259,278 | 39,265 | 15.1 |

| 1983 | 231,700 | 35,303 | 15.2 |

| 1982 | 229,412 | 34,398 | 15.0 |

| 1965 | 191,413 | 33,185 | 17.3 |

| 1964 | 189,710 | 36,055 | 19.0 |

| 1963 | 187,258 | 36,436 | 19.5 |

| 1962 | 184,276 | 38,625 | 21.0 |

| 1961 | 181,277 | 39,628 | 21.9 |

| 1960 | 179,503 | 39,851 | 22.2 |

| 1959 | 176,557 | 39,490 | 22.4 |

| Memo | |||

| 2009 | 303,820 | 46,180 | 14.3 |

| 2008 | 301,041 | 38,829 | 13.2 |

| 2007 | 298,699 | 37,276 | 12.5 |

| 2006 | 296,450 | 36,460 | 12.3 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 62.

Millions in poverty in the calendar year in which the recession ended and in the first calendar year after the recession are provided in Table 2. There have been increases in the number of people in poverty in the first calendar years after the recessions since 1980. The brief recession of Jan to Jul 1980 experienced the highest increase in the first calendar year of 1.0 percent and 2.550 million more in poverty. In the three recessions before 1980 shown in Table 2, the number of people in poverty fell in the first calendar year after the end of the recession.

Table 2, US, Millions in Poverty in the Calendar Year in which Recession Ended and in the First Calendar Year after Recession, Millions and ∆%

| Millions | % | Millions | % | Change Millions | ∆% | |

| Dec 2007 to Jun 2009 | ||||||

| 2009 | 43.569 | 14.3 | ||||

| 2010 | 46.180 | 15.1 | 2.611 | 0.8 | ||

| Mar 2001 to Nov 2001 | ||||||

| 2001 | 32.907 | 11.7 | ||||

| 2002 | 34.570 | 12.1 | 1.663 | 0.4 | ||

| Jul 1990 to Mar 1991 | ||||||

| 1991 | 35.708 | 14.2 | ||||

| 1992 | 38.014 | 14.8 | 2.306 | 0.6 | ||

| Jul 1981 to Nove 1982 | ||||||

| 1982 | 34.398 | 15.0 | ||||

| 1983 | 35.303 | 15.2 | 0.905 | 0.2 | ||

| Jan 1980 to July 1980 | ||||||

| 1980 | 29.272 | 13.0 | ||||

| 1981 | 31.382 | 14.0 | 2.550 | 1.0 | ||

| Nov 1973 to Mar 1975 | ||||||

| 1975 | 25.887 | 12.3 | ||||

| 1976 | 24,975 | 11.8 | -0.902 | -0.5 | ||

| Dec 1960 to Nov 1970 | ||||||

| 1970 | 25.420 | 12.6 | ||||

| 1971 | 25.559 | 12.5 | -0.139 | -0.1 | ||

| Apr 1960 to Feb 1961 | ||||||

| 1961 | 39.628 | 21.9 | ||||

| 1962 | 38.625 | 21.0 | -1.003 | -0.9 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 16.

Another dramatic fact revealed by DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith (2011) is the increase in the number people without health insurance shown in Table 3 at 49.904 million for 2010. Approximately 16.3 percent of the US population does not have health insurance.

Table 3, US, People without Health Insurance in the Final Year of Recession and in the First Calendar Year after Recession Ended, Millions and Percent

| Millions Without Health Insurance | Percent of Population | |

| Recession Dec 2007 to Jun 2009 | ||

| 2009 | 49.985 | 16.1 |

| 2010 | 49.904 | 16.3 |

| Change | 0.919 | 0.2 |

| Recession Mar 2001 to Nov 2001 | ||

| 2001 | 38.023 | 13.5 |

| 2002 | 39.776 | 13.9 |

| Change | 1.753 | 0.4 |

| Recession Jul 1990 to Mar 1991 | ||

| 1991 | 35.445 | 14.1 |

| 1992 | 38.641 | 15.0 |

| Change | 3.196 | 0.9 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 28.

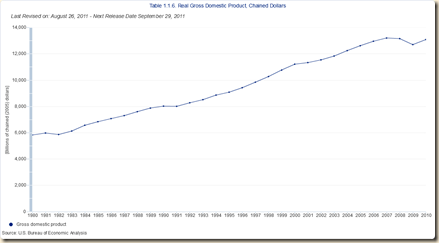

Although US GDP expanded during six consecutive quarter from IIIQ2009 to IVQ2010, US median household income dropped by 2.3 percent from $50,599 in 2009 to $49,445 in 2010. Table 4 shows that US median household income has declined from $52,823 million in 2007 to $49,445 million in 2010 or by 6.4 percent. The data are adjusted for inflation and expressed in constant 2010 dollars.

Table 4, US, Median Household Income, Dollars and ∆%

| 2010 | 2009 | 2007 | |

| Total Number of Households | 118,682 | 117,538 | 116,783 |

| Median Income Dollars | 49,445 | 50,599 | 52,823 |

| ∆% 2010/2009 | -2.3 | ||

| ∆% 2010/2007 | -6.4 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 6, 33.

Numbers of households in the US, median income in constant 2010 dollars and mean income 2010 dollars are provided in Table 5. There is a dramatic fact in Table 5: inflation-adjusted median household income in the US is higher in all years from 1997 to 2010 than the $49,445 of 2010. The contraction and low rate of growth in the expansion have resulted in the destruction of the progress in household income accomplished in 13 years of technological advance and use of humans, machines and natural resources in economic activity. The median measures the center of the middle class of the US that is no better off after 13 years of efforts. There is sharp contrast with the 1980s. Rapid economic growth after the contraction from Jul 1981 to Nov 1982 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html) resulted in an increase of household median income from $43,453 in 1983 to $49,076 in 1989, or by 12.9 percent. Another fact of Table 5 is that household income in 2010 of $49,455 is virtually the same as $49,076 in 1989. The typical household in the US is not better off than in 1989, which is separated from the present by 21 years of efforts.

Table 5, Median and Mean Household Income in 2010 Constant Dollars

| Year | # Households | Median Income 2010 Dollars | Mean Income 2010 Dollars |

| 2010 | 118,682 | 49,445 | 67,530 |

| 2009 | 117,538 | 50,599 | 69,098 |

| 2008 | 117,181 | 50,939 | 69,290 |

| 2007 | 116,783 | 52,823 | 71,095 |

| 2006 | 116,011 | 52,124 | 71,988 |

| 2005 | 114,384 | 51,739 | 70,746 |

| 2004 | 113,343 | 51,174 | 69,795 |

| 2003 | 112,000 | 51,353 | 70,023 |

| 2002 | 111,278 | 51,398 | 70,114 |

| 2001 | 109,297 | 52,005 | 71,685 |

| 2000 | 108,209 | 53,164 | 72,339 |

| 1999 | 106,434 | 53,252 | 71,626 |

| 1998 | 103,874 | 51,944 | 69,270 |

| 1997 | 102,528 | 50,123 | 67,307 |

| 1996 | 101,018 | 49,112 | 65,207 |

| 1995 | 99,627 | 48,408 | 63,838 |

| 1994 | 98,990 | 46,937 | 62,750 |

| 1993 | 97,107 | 46,419 | 61,556 |

| 1992 | 96,426 | 46,646 | 59,137 |

| 1991 | 95,669 | 47,032 | 59,203 |

| 1990 | 94,312 | 48,423 | 60,487 |

| 1989 | 93,347 | 49,076 | 62,003 |

| 1988 | 92,830 | 48,216 | 60,245 |

| 1987 | 91,124 | 47,848 | 59,505 |

| 1986 | 89,479 | 47,256 | 58,382 |

| 1985 | 88,458 | 45,640 | 56,167 |

| 1984 | 86,789 | 44,802 | 54,849 |

| 1983 | 85,407 | 43,453 | 52,849 |

| 1982 | 83,918 | 43,758 | 52,735 |

| 1981 | 82,527 | 43,876 | 52,417 |

| 1980 | 82,368 | 44,616 | 53,064 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 34.

The percentage change in median household income and the change in number of workers with earnings in the first calendar years after recessions are provided in Table 6. The first calendar year after the end of recession in 2010 is by far the worst of any such year in recessions since 1970. Household median income fell 2.3 percent from 2009 to 2010 and the number of workers with earnings fell by 1.608 million. The first calendar year 2010 after the end of recession in 2009 is the only in the recessions back to 1970 in which there was decline of the number of workers with earnings and the only one also with negative change in full-time year-round workers.

Table 6, Percentage Change in Median Household Income and Change in Number of Workers with Earnings in First Calendar Years after Recessions, ∆% and Thousands

| Median Household Income ∆% | Change in Number of Workers with Earnings Thousands | Change in Full-time Year-round Workers Thousands | |

| Recession Dec 2007 to June 2009 | |||

| 2010 | -2.3 | -1,608 | -24 |

| Recession Mar 2001 to Nov 2001 | |||

| 2002 | -1.2 | 470 | 286 |

| Recession Jul 1990 to Mar 1991 | |||

| 1992 | -0.8 | 1,692 | 1,468 |

| Recession Jul 1981 to Nov 1982 | |||

| 1983 | -0.7 | 1,696 | 2,887 |

| Recession Jan 1980 to Jul 1980 | |||

| 1981 | -1.7 | 995 | 362 |

| Recession Nov 1973 to Mar 1975 | |||

| 1976 | 1.7 | 2,821 | 1,538 |

| Recession Dec 1960 to Nov 1970 | |||

| 1971 | -1.0 | 1,277 | 1,213 |

Source: DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith 2011, 7.

Characteristics of four cyclical contractions are provided in Table 7 with the first column showing the number of quarter of contraction, the second column the cumulative percentage contraction and the final column the average quarterly rate of contraction in annual equivalent rate. There were two contractions from IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 and IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 separated by three quarters of expansion. The drop of output combining the declines in these two contractions is 4.8 percent, which is almost equal to the decline of 5.1 percent in the contraction from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. In contrast, during the Great Depression in the four years of 1930 to 1933, GDP in constant dollars fell 26.5 percent cumulatively and fell 45.6 percent in current dollars (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 150-2, Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2009b), 205-7). The comparison of the global recession after 2007 with the Great Depression is common but entirely misleading

Table 7, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Percentage Contraction and Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate in Cyclical Contractions

| Number of Quarters | Cumulative Percentage Contraction | Average Percentage Annual Equivalent Rate | |

| IIQ1953 to IIQ1954 | 4 | -2.5 | -0.63 |

| IIIQ1957 to IIQ1958 | 3 | -3.1 | -9.0 |

| IQ1980 to IIIQ1980 | 2 | -2.2 | -1.1 |

| IIIQ1981 to IVQ1982 | 4 | -2.7 | -0.67 |

| IVQ2007 to IIQ2009 | 6 | -5.1 | -0.87 |

Source: Business Cycle Reference Dates: http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html

Data: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table 8 shows the extraordinary contrast between the mediocre average annual equivalent growth rate of 2.4 percent of the US economy in the eight quarters of the current cyclical expansion and the average of 6.2 percent in the four earlier cyclical expansions. The BEA data for the two quarters of 2011 show the economy in standstill with annual equivalent growth of 0.7 percent. The expansion of IQ1983 to IV1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.7 percent.

Table 8, US, Number of Quarters, Cumulative Growth and Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate in Cyclical Expansions

| Number | Cumulative Growth ∆% | Average Annual Equivalent Growth Rate | |

| IIIQ 1954 to IQ1957 | 11 | 12.6 | 4.4 |

| IIQ1958 to IIQ1959 | 5 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| IIQ1975 to IVQ1976 | 8 | 9.5 | 4.6 |

| IQ1983 to IV1985 | 13 | 19.6 | 5.7 |

| Average Four Above Expansions | 6.2 | ||

| IIIQ2009 to IIQ2011 | 8 | 4.9 | 2.4 |

Source: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

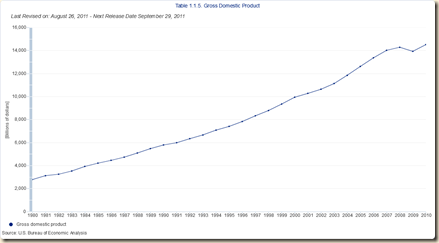

Chart 1 shows US real quarterly GDP growth from 1980 to 1989. The economy contracted during the recession and then expanded vigorously throughout the 1980s, rapidly eliminating the unemployment caused by the contraction.

Chart 1, US, Real GDP, 1980-1989

Source: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart 2 shows the entirely different situation of the real quarterly GDP in the US between 2007 and 2011. The economy has underperformed during the first eight quarters of expansion for the first time in the comparable contractions since the 1950s. The US economy now is in a dangerous standstill.

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhCTNhHfavlIyrof9prtmupznEfMvPKnawuY8JacoiJzW44ND8rxZZe64ayMk1QjttFH2wyfPVM6N07H9ORfaDUgJJFp347p6U8hwFkXgH54inBH-BrTy4mK7WCSQ9Wm92_i-5jCFYKWPA/?imgmax=800)

Source: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

As shown in Tables 7 and 8 above the loss of real GDP in the US during the contraction was 5.1 percent but the gain in the cyclical expansion has been only 4.9 percent. As a result, the level of real GDP in IIQ2011 is lower by 0.5 percent than the level of real GDP in IVQ2007. Table 9 provides in the first column real GDP in billions of chained 2005 dollars. The second column provides the percentage change of the quarter relative to IVQ2007; the third column provides the percentage change relative to the prior quarter; and the final column provides the percentage change relative to the same quarter a year earlier. The contraction actually concentrated in two quarters: decline of 2.3 percent in IVQ2008 relative to the prior quarter and decline of 1.7 percent in IQ2009 relative to IVQ2008. The combined fall of GDP in IVQ2008 and IQ2009 was 4 percent (1.023 x 1.017). Those two quarters coincided with the worst effects of the financial crisis. GDP fell 0.2 percent in IIQ2009 but grew 0.4 percent in IIIQ2009, which is the beginning of recovery in the cyclical dates of the NBER. Most of the recovery occurred in three successive quarters from IVQ2009 to IIQ2010 of equal growth at 0.9 percent for cumulative growth in those three quarters of 2.7 percent. The economy lost momentum already in IIIQ2010 and IVQ2010 growing at 0.6 percent in each quarter. The economy then stalled during the first half of 2011 with growth of 0.1 percent in IQ2011 and 0.25 percent in IIQ2011. Growth in a quarter relative to a year earlier in Table 9 slows from over 3 percent during three consecutive quarters from IIQ2010 to IVQ2010 to 2.2 percent in IQ2011 and 1.5 percent in IIQ2011. The critical question for which there is not yet definitive solution is whether what lies ahead is growth recession with the economy crawling and unemployment/underemployment at extremely high levels or another contraction.

Table 9, US, Real GDP and Percentage Change Relative to IVQ2007 and Prior Quarter, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars and ∆%

| Real GDP, Billions Chained 2005 Dollars | ∆% Relative to IVQ2007 | ∆% Relative to Prior Quarter | ∆% | |

| IVQ2007 | 13,326.0 | NA | NA | 2.2 |

| IQ2008 | 13,266.8 | -0.4 | -0.4 | 1.6 |

| IIQ2008 | 13,310.5 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| IIIQ2008 | 13,186.9 | -1.0 | -0.9 | -0.6 |

| IVQ2008 | 12,883.5 | -3.3 | -2.3 | -3.3 |

| IQ2009 | 12,663.2 | -4.9 | -1.7 | -4.5 |

| IIQ2009 | 12,641.3 | -5.1 | -0.2 | -5.0 |

| IIIQ2009 | 12,694.5 | -4.7 | 0.4 | -3.7 |

| IV2009 | 12,813.5 | -3.8 | 0.9 | -0.5 |

| IQ2010 | 12,937.7 | -2.9 | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| IIQ2010 | 13,058.5 | -1.8 | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| IIIQ2010 | 13,139.6 | -1.4 | 0.6 | 3.5 |

| IVQ2010 | 13,216.1 | -0.8 | 0.6 | 3.1 |

| IQ2011 | 13,227.9 | -0.7 | 0.1 | 2.2 |

| IIQ2011 | 13,260.5 | -0.5 | 0.25 | 1.5 |

Source: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1

Some common explanations for the current slump are not valid. Negative effects of weak housing currently are inferior compared with negative exports in the 1980s that gave the pejorative name of “rust belt” to the US industrial corridor. Growth originates in aggregate demand consisting of investment and consumption. Taylor (2011Jul21) finds that real GDP growth currently is 60 to 70 percent lower than in the recovery of the 1980s, which is also the case of consumption and investment. Another common misperception is that there has been a systemic financial crisis with many ignoring the debt crisis of 1982 when US money-center banks had more than 40 percent of their capital in loans to emerging countries in default or near default. Several countries that had borrowed for financing balance of payments deficits declared moratoriums on their foreign debts, impairing balance sheets of money-center banks (see, for example, in vast literature, Krugman 1994, Pelaez 1986, 1987). The increase in interest rates to deal with stagflation caught the banking industry with short-dated funding and long-term fixed-rate assets. In a parallel of what could happen when monetary policy abandons its near zero interest rates, 1150 US commercial banks, close to 8 percent of the industry, failed, almost twice the number of banks that failed since establishment of the FDIC in 1934 until 1983 (Benston and Kaufman 1997, 139; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 72-7). More than 900 savings and loans associations, equivalent to around 25 percent of the industry, had to be closed, merged or placed in conservatorship (Ibid). Taxpayer funds in the value of $150 billion were used in the resolution of failed savings and loans institutions. In terms of relative dimensions, $150 billion was equivalent to 2.6 percent of GDP of $5800 billion in 1990 and 3.6 percent of GDP of $4217 billion in 1985 (http://www.bea.gov/national/nipaweb/TableView.asp?SelectedTable=5&ViewSeries=NO&Java=no&Request3Place=N&3Place=N&FromView=YES&Freq=Year&FirstYear=1980&LastYear=1990&3Place=N&Update=Update&JavaBox=no). The equivalent in terms of 2.6 to 3.6 percent of US GDP in 2010 of $14,657 billion would be $381 billion to $528 billion (data from Ibid). Wide swings in interest rates resulting from aggressive monetary policy can wreck the balance sheets of families, financial institutions and companies while posing another recession risk. While it is true that monetary policy can increase interest rates instantaneously, the increase from zero percent toward much higher levels to contain inflation can have devastating effects on the world economy.

The Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States provided by the Federal Reserve (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf) is rich in valuable information. Table 10, updated in this blog for every new quarterly release, shows the balance sheet of US households combined with nonprofit organizations in 2007, IQ2011 and IIQ2011. The data show the strong shock to US wealth during the contraction. Assets fells from $78.6 trillion in 2007 to $72.5 trillion in IQ2011 even after six consecutive quarters of growth, that is, by about $6.1 trillion or 7.8 percent. Assets continued to fall in IIQ2011 to $72.3 trillion, by an additional drop of $153 billion equivalent to a loss of 0.2 percent. The cumulative loss between 2007 and IIQ2011 is $6.3 trillion or a drop of 8.0 percent, even after eight consecutive quarter of GDP growth. Liabilities declined from $14.4 trillion in 2007 to $13.9 trillion in IIQ2011 or by $509 billion equivalent to decline by $3.5 trillion. Net worth shrank from $64.3 trillion in 2007 to $58.5 trillion in IIQ2011, that is, $5.8 trillion equivalent to decline of 9.0 percent. There was a brutal decline from 2007 to IIQ2011 of $5.1 trillion in real estate assets or by 21.9 percent. The National Association of Realtors estimated that the gains in net worth in homes by Americans were about $4 trillion between 2000 and 2005 (quoted in Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 224-5).

Table 10, US, Balance Sheet of Households and Nonprofit Organizations, Billions of Dollars Outstanding End of Period, NSA

| 2007 | IQ2011 | IIQ2011 | |

| Assets | 78,637.6 | 72,479.3 | 72,326.2 |

| Nonfinancial | 28,002.6 | 23,195.4 | 23,181.6 |

| Real Estate | 23,272.3 | 18,251.1 | 18,160.7 |

| Durable Goods | 4,468.3 | 4,629.1 | 4,698.8 |

| Financial | 50,635.0 | 49,283.8 | 49,144.6 |

| Deposits | 7,406.0 | 7,913.3 | 8,053.7 |

| Credit Market | 4,072.3 | 4,369.6 | 4,130.1 |

| Mutual Fund | 4,596.8 | 5,091.6 | 5,108.7 |

| Equities Corporate | 9,633.2 | 8,991.5 | 8,946.3 |

| Equity Noncorporate | 8,755.8 | 6,586.8 | 6,578.8 |

| Pension | 13,390.7 | 13,498.0 | 13,423.9 |

| Liabilities | 14,371.5 | 13,866.8 | 13,862.7 |

| Home Mortgages | 10,542.1 | 9,982.0 | 9,934.9 |

| Consumer C | 2,555.3 | 2,401.9 | 2,423.5 |

| Net Worth | 64,266.1 | 58,612.5 | 58,463.5 |

Net Worth = Assets - Liabilities

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf

Let V(T) represent the value of the firm’s equity at time T and B stand for the promised debt of the firm to bondholders and assume that corporate management, elected by equity owners, is acting on the interests of equity owners. Robert C. Merton (1974, 453) states:

“On the maturity date T, the firm must either pay the promised payment of B to the debtholders or else the current equity will be valueless. Clearly, if at time T, V(T) > B, the firm should pay the bondholders because the value of equity will be V(T) – B > 0 whereas if they do not, the value of equity would be zero. If V(T) ≤ B, then the firm will not make the payment and default the firm to the bondholders because otherwise the equity holders would have to pay in additional money and the (formal) value of equity prior to such payments would be (V(T)- B) < 0.”

Pelaez and Pelaez (The Global Recession Risk (2007), 208-9) apply this analysis to the US housing market in 2005-2006 concluding:

“The house market [in 2006] is probably operating with low historical levels of individual equity. There is an application of structural models [Duffie and Singleton 2003] to the individual decisions on whether or not to continue paying a mortgage. The costs of sale would include realtor and legal fees. There could be a point where the expected net sale value of the real estate may be just lower than the value of the mortgage. At that point, there would be an incentive to default. The default vulnerability of securitization is unknown.”

There are multiple important determinants of the interest rate: “aggregate wealth, the distribution of wealth among investors, expected rate of return on physical investment, taxes, government policy and inflation” (Ingersoll 1987, 405). Aggregate wealth is a major driver of interest rates (Ibid, 406). Unconventional monetary policy, with zero fed funds rates and flattening of long-term yields by quantitative easing, causes uncontrollable effects on risk taking that can have profound undesirable effects on financial stability. Excessively aggressive and exotic monetary policy is the main culprit and not the inadequacy of financial management and risk controls.

The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Ibid). According to a subsequent restatement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption decisions is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r →0, W grows without bound, W→∞.

Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment but the exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at close to zero interest rates, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV) (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html).

The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper to purchase default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and operated with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity because of the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions because the put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4).

Table 11 summarizes the brutal drops in assets and net worth of US households and nonprofit organizations from 2007 to IQ2011 and IIQ2011. Between 2007 and IIQ2011, real estate fell in value by $5.1 trillion and financial assets by $1.5 trillion, explaining most of the drop in net worth of $6.3 trillion. The near standstill of the US economy growing in the first half of 2011 at the annual equivalent rate of 0.7 percent is accompanied by a drop of net worth of households and nonprofit organizations of $$5.8 trillion.

Table 11, US, Difference of Balance Sheet of Households and Nonprofit Organizations in Millions of Dollars from 2007 to IQ2011 and IIQ2011

| IQ2011 | IIQ2011 | |

| Assets | -6,6158.3 | -6,311.4 |

| Nonfinancial | -4,807.2 | -4,821.0 |

| Real Estate | -5,012.2 | -5,111.6 |

| Financial | -1,315.2 | -1,490.4 |

| Liabilities | -504.7 | -508.8 |

| Net Worth | -5,653.6 | -5,802.6 |

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf

The report on the Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States also provides the value and change in debt of the nonfinancial sector, shown in Table 12. Households increased debt by 10 percent in 2006 but have been reducing their debt continuously. Business had not been as exuberant in acquiring debt and has been moderately increasing debt benefitting from historically low costs while increasing cash holdings to around $2 trillion because of the uncertainty of capital budgeting. States and local government were forced into increasing debt by the decline in revenues but began to contract in IQ2011, reducing debt even further in IIQ2011. Opposite behavior is found for the federal government that has been rapidly accumulating debt but without success in the self-assigned goal of promoting economic growth.

Table 12, US, Percentage Change of Nonfinancial Domestic Sector Debt

| Total | House -holds | Business | State & Local Govern-ment | Federal | |

| IIQ 2011 | 3.0 | -0.6 | 4.0 | -3.2 | 8.6 |

| IQ 2011 | 1.9 | -2.0 | 2.8 | -4.2 | 7.9 |

| IVQ 2010 | 5.1 | -0.8 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 16.4 |

| IIIQ 2010 | 3.9 | -2.1 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 16.0 |

| IIQ 2010 | 3.9 | -2.1 | -1.7 | -0.3 | 22.5 |

| IQ 2010 | 3.5 | -3.1 | -0.5 | 4.5 | 20.6 |

| 2010 | 4.2 | -2.0 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 20.2 |

| 2009 | 3.1 | -1.6 | -2.7 | 4.9 | 22.7 |

| 2008 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 24.2 |

| 2007 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 13.1 | 9.5 | 4.9 |

| 2006 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 3.9 |

| 2005 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 10.2 | 7.0 |

| 2004 | 8.9 | 11.1 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 9.0 |

| 2003 | 8.1 | 11.9 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 10.9 |

| 2002 | 7.4 | 10.8 | 2.8 | 11.1 | 7.6 |

| 2001 | 6.3 | 9.6 | 5.7 | 8.8 | -0.2 |

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/Current/z1.pdf

II “Let’s Twist Again” Monetary Policy. Meulendyke (1998, 39) describes the coordination of policy by Treasury and the FOMC in the beginning of the Kennedy administration in 1961:

“In 1961, several developments led the FOMC to abandon its “bills only” restrictions. The new Kennedy administration was concerned about gold outflows and balance of payments deficits and, at the same time, it wanted to encourage a rapid recovery from the recent recession. Higher rates seemed desirable to limit the gold outflows and help the balance of payments, while lower rates were wanted to speed up economic growth.

To deal with these problems simultaneously, the Treasury and the FOMC attempted to encourage lower long-term rates without pushing down short-term rates. The policy was referred to in internal Federal Reserve documents as “operation nudge” and elsewhere as “operation twist.” For a few months, the Treasury engaged in maturity exchanges with trust accounts and concentrated its cash offerings in shorter maturities.

The Federal Reserve participated with some reluctance and skepticism, but it did not see any great danger in experimenting with the new procedure.

It attempted to flatten the yield curve by purchasing Treasury notes and bonds while selling short-term Treasury securities. The domestic portfolio grew by $1.7 billion over the course of 1961. Note and bond holdings increased by a substantial $8.8 billion, while certificate of indebtedness holdings fell by almost $7.4 billion (Table 2). The extent to which these actions changed the yield curve or modified investment decisions is a source of dispute, although the predominant view is that the impact on yields was minimal. The Federal Reserve continued to buy coupon issues thereafter, but its efforts were not very aggressive. Reference to the efforts disappeared once short-term rates rose in 1963. The Treasury did not press for continued Fed purchases of long-term debt. Indeed, in the second half of the decade, the Treasury faced an unwanted shortening of its portfolio. Bonds could not carry a coupon with a rate above 4 1/4 percent, and market rates persistently exceeded that level. Notes—which were not subject to interest rate restrictions—had a maximum maturity of five years; it was extended to seven years in 1967.”

The term “operation twist” grew out of the dance “twist” popularized by successful musical performer Chubby Chekker (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWaJ0s0-E1o). Financial markets are widely anticipating the return of Chubby Chekker’s “twisting time” or “let’s twist again” monetary policy perhaps even during the two-day meeting of the FOMC scheduled for Sep 20 to Sep 21 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm#9662). Operation twist is discussed in this section. More technical analysis, references and its relation to quantitative easing are provided for readers interested in more quantitative analysis in IIA Appendix: Analysis, Measurement and Evaluation of Operation Twist and Quantitative Easing.

The limited effects of operation twist were analyzed by Modigliani and Stuch (1966, 1967) with empirical estimation methods of their time in the 1960s. Swanson (2011Mar) provides analysis and measurement using current state of the art estimation methods.

Swanson (2011Mar) analyzes the policy mechanics of operation twist. President Kennedy faced two policy challenges after assuming office in Jan 1961: (1) international financial funds flowed in pursuit of higher short-term interest rates in Europe relative to those in the US that were restricted by prohibition of payment of interest on demand deposits and ceilings of interest on time deposits as provided by the Banking Act of 1933 and implemented by Regulation Q (for Regulation Q see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 74-5); and (2) the US was recovering from strong recession that lasted from IIQ1960 (Apr) to IQ1961 (Feb) (http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html). The objective of operation twist was maintaining stable or increasing short-term interest rates to prevent financial funds from flowing away from the US into Europe while simultaneously reducing long-term interest rates to stimulate investment and consumption, or aggregate demand. President Kennedy announced coordination of Treasury and FOMC policy as follows:

1. Treasury. The US Treasury would increase the issuance of short term securities while at the same time reduce the issuance of long-term securities. The desired effects of this policy would be in two forms:

i. The increase in the issuance of short-term Treasury securities would displace the supply curve of short-term securities downward and to the right. Assuming stable demand, the price of short-term Treasury securities would fall, which is equivalent to an increase in short-term interest rates that would prevent net outflows of capital from the US. There is a critical assumption here that capital flows among nations are determined by short-term interest rate differentials

ii. The reduction in the supply of long-term Treasury securities would cause displacement of the supply curve upward and to the left. Assuming stable demand, the price of long-term securities increases, which is equivalent to reducing yields of long-term securities

2. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC would decide to sell short-term securities and buy long-term securities with the following desired effects:

i. The sale of short-term Treasury securities could displace the supply curve downwardly and to the right. Assuming stable demand, the price of short-term Treasury securities would fall, which is equivalent to an increase in short-term rates of Treasury securities designed to prevent net outflows of international capital from the US

ii. The purchase of long-term Treasury securities would displace demand for long-term Treasury securities upward and to the right. The price of long-term Treasury securities would increase, which is equivalent to a reduction of yields of long-term Treasury securities

A widely prevailing view of the limited scope and lack of effects on real economic activity of operation twist is provided by Blinder (2000, 1097):

“If the overnight (nominal) interest rate is zero, but other interest rates are not, the central bank can use open market operations in longer-dated securities to try to drive down longer-term interest rates. But here we encounter a problem analogous to the one that bedevils foreign exchange intervention: If the pure expectations theory of the term structure holds and short rates are expected to remain (approximately) zero for a while, then intermediate-term rates will be (approximately) zero, too. And, to bring down truly long rates, the bank would have to convince the market that the zero-interest-rate period would last many years!

Fortunately, the pure expectations theory does not hold. At a minimum, long rates include a variable term premium (often called a risk premium) which is potentially manipulable by changing the relative supplies of longs and shorts. But note that open market purchases of long bonds by the central bank are equivalent to open market purchases of bills plus a "twist" operation that sells bills and buys bonds. Most of us are skeptical that such twist operations have dramatic effects on the yield curve, much less on economic activity. America's "Operation Twist" of the 1960s is widely remembered as a failure, but that may be because the scale of the operation was so small. Once again, the message may be: Think big.”

Swanson (2011Mar, 5) provides evidence that operation twist was comparable in size to quantitative easing two (QE2). Operation twist was on the order of $8.8 billion while QE2 was $600 billion but nominal values are misleading as operation twist was equivalent to 1.7 percent of GDP, which is not insignificant relative to 4.1 percent of GDP for QE2. Operation twist was equivalent to 4.7 percent of US Treasury debt, which is not insignificant relative to 7.0 percent for QE2. Operation twist was equivalent to 4.5 percent of US agency-guaranteed debt, which is higher than 3.7 percent for QE2. Finally, operation twist was coordinated with Treasury whereas this was not the case of QE2.

The limited size of operation twist is related to the findings of Modigliani and Sutch (1966, 196) that:

“1. The expectation model can account remarkably well for the relation between short- and long-term rates in the United States. Furthermore, the prevailing expectations of long-term rates involve a blending of extrapolation of very recent changes and regression toward a long term normal level.

2. There is no evidence that the maturity structure of the federal debt, or changes in this structure, exert a significant, lasting or transient, influence on the relation between the two rates.

3. The spread between long and short rates in the government market since the inception of Operation Twist was on the average some twelve base points below what one might infer from the pre-Operation Twist relation. This discrepancy seems to be largely attributable to the successive increase in the ceiling rate under Regulation Q which enabled the newly invented CD's to exercise their maximum influence.

4. Any effects, direct or indirect, of Operation Twist in narrowing the spread which further study might establish, are most unlikely to exceed some ten to twenty base points a reduction that can be considered moderate at best.”

Swanson (2011Mar, 31-2) finds with modern state of the art estimation methods operation twist reduced yields of long-term US treasury securities by 15 basis points:

“The present paper has reexamined Operation Twist using a modern high-frequency event-study approach, which avoids the problems with lower-frequency methods discussed above. In contrast to Modigliani and Sutch, we find that Operation Twist had a highly statistically significant impact on longer-term Treasury yields. However, consistent with those authors, we find that the size of the effect was moderate, amounting to about 15 basis points. This estimate is also consistent with the lower end of the range of estimates of Treasury supply effects in the literature.”

The effects of quantitative easing or operation twist of 15 basis points are comparable to those of tightening of the fed funds rate by 100 basis points, as measured by Gürkaynak, Sack and Swanson (2005, 84):

“In particular, we estimate that a 1 percentage point surprise tightening in the federal funds rate leads, on average, to a 4.3 percent decline in the S&P 500 and increases of 49, 28, and 13 bp in two-, five-, and ten-year Treasury yields, respectively.”

There is another operational factors of the “let’s twist again” monetary policy. Swanson (2011Mar) also reminds that lowering long-term yields in a new twist of the yield curve does not require increasing short-term rates as in the part of operation twist policy designed to prevent net capital outflows of the US. The desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York can continue to implement the target of fed funds rate of 0 to ¼ percent.

The crucial issue here is if lowering the yields of long-term Treasury securities would have any impact on investment and consumption or aggregate demand. The decline of long-term yields Treasury securities would have to cause decline of yields of asset-backed securities used to securitize loans for investment by firms and purchase of durable goods by consumers. The decline in costs of investment and consumption of durable goods would ultimately have to result in higher investment and consumption.

IIA Appendix: Analysis, Measurement and Evaluation of Operation Twist and Quantitative Easing. This appendix is divided into two subsections: IIA1 Operation Twist that reviews the analysis of lowering long-term yields; and IIA2 that reviews the analysis of quantitative easing.

IIA1 Operation Twist. Swanson finds three disadvantages in the time series approach of Modigliani and Sutch who relied on estimation methods available in the mid 1960s. (1) Treasury yields are very sensitive to expectations of inflation and the future path of fed funds rates that are not captured by quarterly data but are isolated in high-frequency observations. (2) The magnitudes of changes in yields by small numbers of basis points would have to be statistically insignificant relative to high standard errors of regressions. (3) There are multiple macroeconomic factors affecting Treasury yields preventing identification of the effects of policy that may not be present in high-frequency observations.

The method used by Swanson is that of event studies popularized by the efficient market hypothesis. Under rational expectations, asset prices incorporate all available information after the announcement (Samuelson 1965; Fama 1970). Swanson identifies six events of which five provide the information to reject the null hypothesis that changes in net supply of long-term bonds do not have effects on Treasury yields of any maturity. The alternative hypothesis is that changes in supply affect yields of Treasury securities.

IIA2 Transmission of Quantitative Easing. Janet L. Yellen, Vice Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, provides analysis of the policy of purchasing large amounts of long-term securities for the Fed’s balance sheet. The new analysis provides now three channels of transmission of quantitative easing to the ultimate objectives of increasing growth and employment and increasing inflation to “levels of 2 percent or a bit less that most Committee participants judge to be consistent, over the long run, with the FOMC’s dual mandate” (Yellen 2011AS, 4, 7):

“There are several distinct channels through which these purchases tend to influence aggregate demand, including a reduced cost of credit to consumers and businesses, a rise in asset prices that boost household wealth and spending, and a moderate change in the foreign exchange value of the dollar that provides support to net exports.”

The new analysis by Yellen (2011AS) is considered below in four separate subsections: IIA2i Theory; IIA2ii Policy; IIA2iii Evidence; and IIA2iv Unwinding Strategy.

IIA2i Theory. The transmission mechanism of quantitative easing can be analyzed in three different forms. (1) Portfolio choice theory. General equilibrium value theory was proposed by Hicks (1935) in analyzing the balance sheets of individuals and institutions with assets in the capital segment consisting of money, debts, stocks and productive equipment. Net worth or wealth would be comparable to income in value theory. Expected yield and risk would be the constraint comparable to income in value theory. Markowitz (1952) considers a portfolio of individual securities with mean μp and variance σp. The Markowitz (1952, 82) rule states that “investors would (or should” want to choose a portfolio of combinations of (μp, that are efficient, which are those with minimum variance or risk for given expected return μp or more and maximum expected μp for given variance or risk or less. The more complete model of Tobin (1958) consists of portfolio choice of monetary assets by maximizing a utility function subject to a budget constraint. Tobin (1961, 28) proposes general equilibrium analysis of the capital account to derive choices of capital assets in balance sheets of economic units with the determination of yields in markets for capital assets with the constraint of net worth. A general equilibrium model of choice of portfolios was developed simultaneously by various authors (Hicks 1962; Treynor 1962; Sharpe 1964; Lintner 1965; Mossin 1966). If shocks such as by quantitative easing displace investors from the efficient frontier, there would be reallocations of portfolios among assets until another efficient point is reached. Investors would bid up the prices or lower the returns (interest plus capital gains) of long-term assets targeted by quantitative easing, causing the desired effect of lowering long-term costs of investment and consumption.

(2) General Equilibrium Theory. Bernanke and Reinhart (2004, 88) argue that “the possibility monetary policy works through portfolio substitution effects, even in normal times, has a long intellectual history, having been espoused by both Keynesians (James Tobin 1969) and monetarists (Karl Brunner and Allan Meltzer 1973).” Andres et al. (2004) explain the Tobin (1969) contribution by optimizing agents in a general-equilibrium model. Both Tobin (1969) and Brunner and Meltzer (1973) consider capital assets to be gross instead of perfect substitutes with positive partial derivatives of own rates of return and negative partial derivatives of cross rates in the vector of asset returns (interest plus principal gain or loss) as argument in portfolio balancing equations (see Pelaez and Suzigan 1978, 113-23). Tobin (1969, 26) explains portfolio substitution after monetary policy:

“When the supply of any asset is increased, the structure of rates of return, on this and other assets, must change in a way that induces the public to hold the new supply. When the asset’s own rate can rise, a large part of the necessary adjustment can occur in this way. But if the rate is fixed, the whole adjustment must take place through reductions in other rates or increases in prices of other assets. This is the secret of the special role of money; it is a secret that would be shared by any other asset with a fixed interest rate.”

Andrés et al. (2004, 682) find that in their multiple-channels model “base money expansion now matters for the deviations of long rates from the expected path of short rates. Monetary policy operates by both the expectations channel (the path of current and expected future short rates) and this additional channel. As in Tobin’s framework, interest rates spreads (specifically, the deviations from the pure expectations theory of the term structure) are an endogenous function of the relative quantities of assets supplied.”

The interrelation among yields of default-free securities is measured by the term structure of interest rates. This schedule of interest rates along time incorporates expectations of investors. (Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1985). The expectations hypothesis postulates that the expectations of investors about the level of future spot rates influence the level of current long-term rates. The normal channel of transmission of monetary policy in a recession is to lower the target of the fed funds rate that will lower future spot rates through the term structure and also the yields of long-term securities. The expectations hypothesis is consistent with term premiums (Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1981, 774-7) such as liquidity to compensate for risk or uncertainty about future events that can cause changes in prices or yields of long-term securities (Hicks 1939; see Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1981, 784; Chung et al. 2011, 22).

(3) Preferred Habitat. Another approach is by the preferred-habitat models proposed by Culbertson (1957, 1963) and Modigliani and Sutch (1966). This approach is formalized by Vayanos and Vila (2009). The model considers investors or “clientele” who do not abandon their segment of operations unless there are extremely high potential returns and arbitrageurs who take positions to profit from discrepancies. Pension funds matching benefit liabilities would operate in segments above 15 years; life insurance companies operate around 15 years or more; and asset managers and bank treasury managers are active in maturities of less than 10 years (Ibid, 1). Hedge funds, proprietary trading desks and bank maturity transformation activities are examples of potential arbitrageurs. The role of arbitrageurs is to incorporate “information about current and future short rates into bond prices” (Ibid, 12). Suppose monetary policy raises the short-term rate above a certain level. Clientele would not trade on this information, but arbitrageurs would engage in carry trade, shorting bonds and investing at the short-term rate, in a “roll-up” trade, resulting in decline of bond prices or equivalently increases in yields. This is a situation of an upward-sloping yield curve. If the short-term rate were lowered, arbitrageurs would engage in carry trade borrowing at the short-term rate and going long bonds, resulting in an increase in bond prices or equivalently decline in yields, or “roll-down” trade. The carry trade is the mechanism by which bond yields adjust to changes in current and expected short-term interest rates. The risk premiums of bonds are positively associated with the slope of the term structure (Ibid, 13). Fama and Bliss (1987, 689) find with data for 1964-85 that “1-year expected returns for US Treasury maturities to 5 years, measured net of the interest rate on a 1-year bond, vary through time. Expected term premiums are mostly positive during good times but mostly negative during recessions.” Vayanos and Vila (2009) develop a model with two-factors, the short-term rate and demand or quantity. The term structure moves because of shocks of short-term rates and demand. An important finding is that demand or quantity shocks are largest for intermediate and long maturities while short-rate shocks are largest for short-term maturities.

IIA2ii Policy. A simplified analysis could consider the portfolio balance equations Aij = f(r, x) where Aij is the demand for i = 1,2,∙∙∙n assets from j = 1,2, ∙∙∙m sectors, r the 1xn vector of rates of return, ri, of n assets and x a vector of other relevant variables. Tobin (1969) and Brunner and Meltzer (1973) assume imperfect substitution among capital assets such that the own first derivatives of Aij are positive, demand for an asset increases if its rate of return (interest plus capital gains) is higher, and cross first derivatives are negative, demand for an asset decreases if the rate of return of alternative assets increases. Theoretical purity would require the estimation of the complete model with all rates of return. In practice, it may be impossible to observe all rates of return such as in the critique of Roll (1976). Policy proposals by the Fed have been focused on the likely impact of withdrawals of stocks of securities in specific segments, that is, of effects of one or several specific rates of return among the n possible rates. There have been six approaches on the role of monetary policy in purchasing long-term securities that have increased the classes of rates of return targeted by the Fed:

i. Suspension of Auctions of 30-year Treasury Bonds. Auctions of 30-year Treasury bonds were suspended between 2001 and 2005. This was Treasury policy not Fed policy. The effects were similar to those of quantitative easing: withdrawal of supply from the segment of 30-year bonds would result in higher prices or lower yields for close-substitute mortgage-backed securities with resulting lower mortgage rates. The objective was to encourage refinancing of house loans that would increase family income and consumption by freeing income from reducing monthly mortgage payments.

ii. Purchase of Long-term Securities by the Fed. Between Nov 2008 and Mar 2009 the Fed announced the intention of purchasing $1750 billion of long-term securities: $600 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities and agency debt announced on Nov 25 and $850 billion of agency mortgaged-backed securities and agency debt plus $300 billion of Treasury securities announced on Mar 18, 2009 (Yellen 2011AS, 5-6). The objective of buying mortgage-backed securities was to lower mortgage rates that would “support the housing sector” (Bernanke 2009SL). The FOMC statement on Dec 16, 2008 informs that: “over the next few quarters the Federal Reserve will purchase large quantities of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities to provide support to the mortgage and housing markets, and its stands ready to expand its purchases of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities as conditions warrant” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm). The Mar 18 statement of the FOMC explained that: “to provide greater support to mortgage lending and housing markets, the Committee decided today to increase the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet further by purchasing up to an additional $750 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities, bringing its total purchases of these securities up to $1.25 trillion this year, and to increase its purchase of agency debt this year by up to $100 billion to a total of up to $200 billion. Moreover, to help improve conditions in private credit markets, the Committee decided to purchase up to $300 billion of longer-term Treasury securities over the next six months” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20090318a.htm). Policy changed to increase prices or reduce yields of mortgage-backed securities and Treasury securities with the objective of supporting housing markets and private credit markets by lowering costs of housing and long-term private credit.

iii. Portfolio Reinvestment. On Aug 10, 2010, the FOMC statement explains the reinvestment policy: “to help support the economic recovery in a context of price stability, the Committee will keep constant the Federal Reserve’s holdings of securities at their current level by reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in long-term Treasury securities. The Committee will continue to roll over the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities as they mature” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20100810a.htm). The objective of policy appears to be supporting conditions in housing and mortgage markets with slow transfer of the portfolio to Treasury securities that would support private-sector markets.

iv. Increasing Portfolio. As widely anticipated, the FOMC decided on Dec 3, 2010: “to promote a stronger pace of economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with its mandate, the Committee decided today to expand its holdings of securities. The Committee will maintain its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its securities holdings. In addition, the Committee intends to purchase a further $600 billion of longer-term Treasury securities by the end of the second quarter of 2011, a pace of about $75 billion per month” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20101103a.htm). The emphasis appears to shift from housing markets and private-sector credit markets to the general economy, employment and preventing deflation.

v. Increasing Stock Market Valuations. Chairman Bernanke (2010WP) explained on Nov 4 the objectives of purchasing an additional $600 billion of long-term Treasury securities and reinvesting maturing principal and interest in the Fed portfolio. Long-term interest rates fell and stock prices rose when investors anticipated the new round of quantitative easing. Growth would be promoted by easier lending such as for refinancing of home mortgages and more investment by lower corporate bond yields. Consumers would experience higher confidence as their wealth in stocks rose, increasing outlays. Income and profits would rise and, in a “virtuous circle,” support higher economic growth. Bernanke (2000) analyzes the role of stock markets in central bank policy (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 99-100). Fed policy in 1929 increased interest rates to avert a gold outflow and failed to prevent the deepening of the banking crisis without which the Great Depression may not have occurred. In the crisis of Oct 19, 1987, Fed policy supported stock and futures markets by persuading banks to extend credit to brokerages. Collapse of stock markets would slow consumer spending.

vi. Devaluing the Dollar. Yellen (2011AS, 6) broadens the effects of quantitative easing by adding dollar devaluation: “there are several distinct channels through which these purchases tend to influence aggregate demand, including a reduced cost of credit to consumers and businesses, a rise in asset prices that boosts household wealth and spending, and a moderate change in the foreign exchange value of the dollar that provides support to net exports.”

IIA2iii Evidence. There are multiple empirical studies on the effectiveness of quantitative easing that have been covered in past posts such as (Andrés et al. 2004, D’Amico and King 2010, Doh 2010, Gagnon et al. 2010, Hamilton and Wu 2010). On the basis of simulations of quantitative easing with the FRB/US econometric model, Chung et al (2011, 28-9) find that:

”Lower long-term interest rates, coupled with higher stock market valuations and a lower foreign exchange value of the dollar, provide a considerable stimulus to real activity over time. Phase 1 of the program by itself is estimated to boost the level of real GDP almost 2 percent above baseline by early 2012, while the full program raises the level of real GDP almost 3 percent by the second half of 2012. This boost to real output in turn helps to keep labor market conditions noticeably better than they would have been without large scale asset purchases. In particular, the model simulations suggest that private payroll employment is currently 1.8 million higher, and the unemployment rate ¾ percentage point lower, that would otherwise be the case. These benefits are predicted to grow further over time; by 2012, the incremental contribution of the full program is estimated to be 3 million jobs, with an additional 700,000 jobs provided by the most recent phase of the program alone.”

An additional conclusion of these simulations is that quantitative easing may have prevented actual deflation. Empirical research is continuing.

IIA2iv Unwinding Strategy. Fed Vice-Chair Yellen (2011AS) considers four concerns on quantitative easing discussed below in turn. First, Excessive Inflation. Yellen (2011AS, 9-12) considers concerns that quantitative easing could result in excessive inflation because fast increases in aggregate demand from quantitative easing could raise the rate of inflation, posing another problem of adjustment with tighter monetary policy or higher interest rates. The Fed estimates significant slack of resources in the economy as measured by the difference of four percentage points between the high current rate of unemployment above 9 percent and the NAIRU (non-accelerating rate of unemployment) of 5.75 percent (Ibid, 2). Thus, faster economic growth resulting from quantitative easing would not likely result in upward rise of costs as resources are bid up competitively. The Fed monitors frequently slack indicators and is committed to maintaining inflation at a “level of 2 percent or a bit less than that” (Ibid, 13), say, in the narrow open interval (1.9, 2.1).

Second, Inflation and Bank Reserves. On Jan 12, the line “Reserve Bank credit” in the Fed balance sheet stood at $2450,6 billion, or $2.5 trillion, with the portfolio of long-term securities of $2175.7 billion, or $2.2 trillion, composed of $987.6 billion of notes and bonds, $49.7 billion of inflation-adjusted notes and bonds, $146.3 billion of Federal agency debt securities, and $992.1 billion of mortgage-backed securities; reserves balances with Federal Reserve Banks stood at $1095.5 billion, or $1.1 trillion (http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1). The concern addressed by Yellen (2011AS, 12-4) is that this high level of reserves could eventually result in demand growth that could accelerate inflation. Reserves would be excessively high relative to the levels before the recession. Reserves of depository institutions at the Federal Reserve Banks rose from $45.6 billion in Aug 2008 to $1084.8 billion in Aug 2010, not seasonally adjusted, multiplying by 23.8 times, or to $1038.2 billion in Nov 2010, multiplying by 22.8 times. The monetary base consists of the monetary liabilities of the government, composed largely of currency held by the public plus reserves of depository institutions at the Federal Reserve Banks. The monetary base not seasonally adjusted, or issue of money by the government, rose from $841.1 billion in Aug 2008 to $1991.1 billion or by 136.7 percent and to $1968.1 billion in Nov 2010 or by 133.9 percent (http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h3/hist/h3hist1.pdf). Policy can be viewed as creating government monetary liabilities that ended mostly in reserves of banks deposited at the Fed to purchase $2.1 trillion of long-term securities or assets, which in nontechnical language would be “printing money” (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html). The marketable debt of the US government in Treasury securities held by the public stood at $8.7 trillion on Nov 30, 2010 (http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2010/opds112010.pdf). The current holdings of long-term securities by the Fed of $2.1 trillion, in the process of converting fully into Treasury securities, are equivalent to 24 percent of US government debt held by the public, and would represent 29.9 percent with the new round of quantitative easing if all the portfolio of the Fed, as intended, were in Treasury securities. Debt in Treasury securities held by the public on Dec 31, 2009, stood at $7.2 trillion (http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2009/opds122009.pdf), growing to Nov 30, 2010, by $1.5 trillion or by 20.8 percent. In spite of this growth of bank reserves, “the 12-month change in core PCE [personal consumption expenditures] prices dropped from about 2 ½ percent in mid-2008 to around 1 ½ percent in 2009 and declined further to less than 1 percent by late 2010” (Yellen 2011AS, 3). The PCE price index, excluding food and energy, is around 0.8 percent in the past 12 months, which could be, in the Fed’s view, too close for comfort to negative inflation or deflation. Yellen (2011AS, 12) agrees “that an accommodative monetary policy left in place too long can cause inflation to rise to undesirable levels” that would be true whether policy was constrained or not by “the zero bound on interest rates.” The FOMC is monitoring and reviewing the “asset purchase program regularly in light of incoming information” and will “adjust the program as needed to meet its objectives” (Ibid, 12). That is, the FOMC would withdraw the stimulus once the economy is closer to full capacity to maintain inflation around 2 percent. In testimony at the Senate Committee on the Budget, Chairman Bernanke stated that “the Federal Reserve has all the tools its needs to ensure that it will be able to smoothly and effectively exit from this program at the appropriate time” (http://federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/bernanke20110107a.htm). The large quantity of reserves would not be an obstacle in attaining the 2 percent inflation level. Yellen (2011A, 13-4) enumerates Fed tools that would be deployed to withdraw reserves as desired: (1) increasing the interest rate paid on reserves deposited at the Fed currently at 0.25 percent per year; (2) withdrawing reserves with reverse sale and repurchase agreement in addition to those with primary dealers by using mortgage-backed securities; (3) offering a Term Deposit Facility similar to term certificates of deposit for member institutions; and (4) sale or redemption of all or parts of the portfolio of long-term securities. The Fed would be able to increase interest rates and withdraw reserves as required to attain its mandates of maximum employment and price stability.

Third, Financial Imbalances. Fed policy intends to lower costs to business and households with the objective of stimulating investment and consumption generating higher growth and employment. Yellen (2011A, 14-7) considers a possible consequence of excessively reducing interest rates: “a reasonable fear is that this process could go too far, encouraging potential borrowers to employ excessive leverage to take advantage of low financing costs and leading investors to accept less compensation for bearing risks as they seek to enhance their rates of return in an environment of very low yields. This concern deserves to be taken seriously, and the Federal Reserve is carefully monitoring financial indicators for signs of potential threats to financial stability.” Regulation and supervision would be the “first line of defense” against imbalances threatening financial stability but the Fed would also use monetary policy to check imbalances (Yellen 2011AS, 17).

Fourth, Adverse Effects on Foreign Economies. The issue is whether the now recognized dollar devaluation would promote higher growth and employment in the US at the expense of lower growth and employment in other countries. The first three concerns are considered below in (IIE) Alternative Interpretations and the fourth in (IIF) World Devaluation Wars.