IMF View of World Economy and Finance, Recovery without Hiring, Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs, Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment, United States Producer Price Index, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016

I IMF View of World Economy and Finance

IA Recovery without Hiring

IA1 Hiring Collapse

IA2 Labor Underutilization

ICA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment

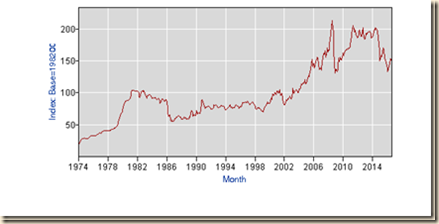

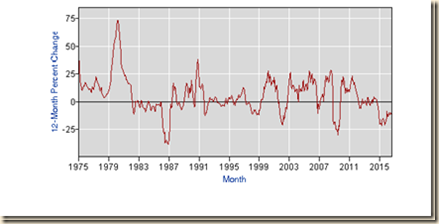

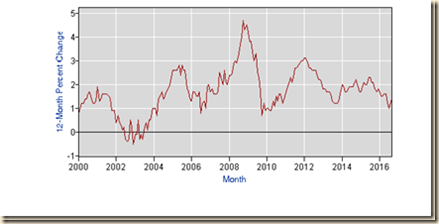

II United States Producer Price Index

II IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

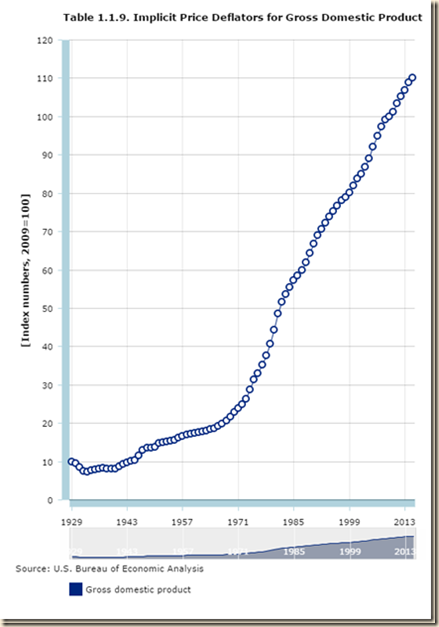

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

I IMF View of World Economy and Finance. The International Financial Institutions (IFI) consist of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank Group, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the multilateral development banks, which are the European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), The Global Recession Risk (2007), 8-19, 218-29, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 114-48, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 145-54). There are four types of contributions of the IFIs:

1. Safety Net. The IFIs contribute to crisis prevention and crisis resolution.

i. Crisis Prevention. An important form of contributing to crisis prevention is by surveillance of the world economy and finance by regions and individual countries. The IMF and World Bank conduct periodic regional and country evaluations and recommendations in consultations with member countries and also jointly with other international organizations. The IMF and the World Bank have been providing the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) by monitoring financial risks in member countries that can serve to mitigate them before they can become financial crises.

ii. Crisis Resolution. The IMF jointly with other IFIs provides assistance to countries in resolution of those crises that do occur. Currently, the IMF is cooperating with the government of Greece, European Union and European Central Bank in resolving the debt difficulties of Greece as it has done in the past in numerous other circumstances. Programs with other countries involved in the European debt crisis may also be developed.

2. Surveillance. The IMF conducts surveillance of the world economy, finance and public finance with continuous research and analysis. Important documents of this effort are the World Economic Outlook (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=29), Global Financial Stability Report (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/index.htm) and Fiscal Monitor (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=262).

3. Infrastructure and Development. The IFIs also engage in infrastructure and development, in particular the World Bank Group and the multilateral development banks.

4. Soft Law. Significant activity by IFIs has consisted of developing standards and codes under multiple forums. It is easier and faster to negotiate international agreements under soft law that are not binding but can be very effective (on soft law see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008c), 114-25). These norms and standards can solidify world economic and financial arrangements.

The objective of this section is to analyze current projections of the IMF database for the most important indicators.

Table I-1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=29) to show GDP in dollars in 2015 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2015 to 2018. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has changed its forecast of the world economy to 3.2 percent in 2015 and 3.1 percent in 2016 but accelerating to 3.4 percent in 2017 and 3.6 percent in 2018. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $34.171 billion of world output of $73,599 billion, or 46.4 percent, but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 1.7 percent on average from 2015 to 2018, in contrast with 3.3 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would grow 14.0 percent in the four years from 2015 to 2017, the G7 as a whole would grow 6.9 percent. The difference in dollars of 2015 is high: growing by 14.0 percent would add around $10.3 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly, two times the output of the economy of Japan of $4,124 billion but growing by 6.9 percent would add $5.1 trillion of output to the world, or about the output of Japan in 2015. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2019 of $29,039 billion, or 39.5 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 18.8 percent or at the average yearly rate of 4.4 percent, contributing $5.5 trillion from 2015 to 2017 or the equivalent of somewhat more than one half the GDP of $11,182 billion of China in 2014. The final four countries in Table I-1 often referred as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output in 2015 adds to $16,354 billion, or 22.2 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 47.9 percent of the combined output of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table I-1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2015 | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | |

| World | 73,599 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| G7 | 34,171 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Canada | 1,551 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| France | 2,420 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| DE | 3,365 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 1,816 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Japan | 4,124 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| UK | 2,858 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| US | 18,037 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Euro Area | 11,601 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| DE | 3,365 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| France | 2,420 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Italy | 1,816 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| POT | 199 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Ireland | 283 | 26.3 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Greece | 195 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

| Spain | 1,200 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| EMDE | 29,039 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 |

| Brazil | 1,773 | -3.8 | -3.3 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Russia | 1,326 | -3.7 | -0.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| India | 2,073 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| China | 11,182 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); POT: Portugal

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx). Table I-2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2014 to 2018 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates for 2014 in Table I-2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high in 2014 for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 13.9 percent for Portugal (POT), 11.3 percent for Ireland, 26.5 percent for Greece, 24.4 percent for Spain and 12.6 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 6.4 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table I-2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2014 | % Labor Force 2015 | % Labor Force 2016 | % Labor Force 2017 | % Labor Force 2018 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Canada | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.9 |

| France | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.3 |

| DE | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Italy | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| Japan | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| UK | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.4 |

| US | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Euro Area | 11.7 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.3 |

| DE | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| France | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.3 |

| Italy | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| POT | 13.9 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 10.3 |

| Ireland | 11.3 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 7.2 |

| Greece | 26.5 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 21.5 | 20.7 |

| Spain | 24.4 | 22.1 | 19.4 | 18.0 | 17.0 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 6.8 | 8.5 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 11.1 |

| Russia | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.5 |

| India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| China | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx) is used to construct the debt/GDP ratios of regions and countries in Table I-3. The concept used is general government debt, which consists of central government debt, such as Treasury debt in the US, and all state and municipal debt. Net debt is provided for all countries except for the only available gross debt for China, Russia and India. The net debt/GDP ratio of the G7 increases from 82.8 in 2014 to 84.4 in 2017. G7 debt is pulled by the high debt of Japan that grows from 126.2 percent of GDP in 2014 to 132.6 percent of GDP in 2018. US general government debt increases from 80.3 percent of GDP in 2014 to 82.1 percent of GDP in 2018. Debt/GDP ratios of countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe are particularly worrisome. General government net debts of Italy, Greece and Portugal exceed 100 percent of GDP or are expected to exceed 100 percent of GDP by 2018. The only country with relatively lower debt/GDP ratio is Spain with 78.6 in 2015, increasing to 82.3 in 2018. Ireland’s debt/GDP ratio decreases from 86.3 in 2014 to 59.8 in 2018. Fiscal adjustment, voluntary or forced by defaults, may squeeze further economic growth and employment in many countries as analyzed by Blanchard (2012WEOApr). Defaults could feed through exposures of banks and investors to financial institutions and economies in countries with sounder fiscal affairs.

Table I-3, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections, General Government Net Debt as Percent of GDP

| % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 82.8 | 82.1 | 84.3 | 84.7 | 84.4 |

| Canada | 28.1 | 26.3 | 26.9 | 25.3 | 23.6 |

| France | 87.4 | 88.2 | 89.2 | 89.8 | 90.0 |

| DE | 50.1 | 47.5 | 45.4 | 43.7 | 42.0 |

| Italy | 112.5 | 113.3 | 113.8 | 113.9 | 112.7 |

| Japan | 126.2 | 125.3 | 127.9 | 130.7 | 132.6 |

| UK | 79.5 | 80.4 | 80.5 | 80.3 | 80.0 |

| US | 80.3 | 79.8 | 82.2 | 82.3 | 82.1 |

| Euro Area | 68.3 | 67.6 | 67.4 | 67.0 | 66.2 |

| DE | 50.1 | 47.5 | 45.4 | 43.7 | 42.0 |

| France | 87.4 | 88.2 | 89.2 | 89.8 | 90.0 |

| Italy | 112.5 | 113.3 | 113.8 | 113.9 | 112.7 |

| POT | 120.0 | 121.6 | 121.9 | 122.2 | 122.2 |

| Ireland | 86.3 | 67.0 | 63.8 | 62.3 | 59.8 |

| Greece* | 180.1 | 176.9 | 183.4 | 184.7 | 184.7 |

| Spain | 78.6 | 79.7 | 81.4 | 82.1 | 82.3 |

| EMDE* | 40.7 | 44.6 | 47.2 | 48.9 | 50.3 |

| Brazil | 33.1 | 36.2 | 45.8 | 50.4 | 53.6 |

| Russia* | 15.9 | 16.4 | 17.1 | 17.9 | 18.6 |

| India* | 68.3 | 69.1 | 68.5 | 67.2 | 65.6 |

| China* | 39.8 | 42.9 | 46.3 | 49.9 | 52.6 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); *General Government Gross Debt as percent of GDP

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The primary balance consists of revenues less expenditures but excluding interest revenues and interest payments. It measures the capacity of a country to generate sufficient current revenue to meet current expenditures. There are various countries with primary surpluses in 2014: Germany 1.7 percent and Italy 1.4 percent. There are also various countries with expected primary surpluses by 2018: Portugal 1.2 percent, Italy 2.1 percent and so on. Most countries in Table I-4 face significant fiscal adjustment in the future without “fiscal space.” Investors in government securities may require higher yields when the share of individual government debts hit saturation shares in portfolios. The tool of analysis of Cochrane (2011Jan, 27, equation (16)) is the government debt valuation equation:

(Mt + Bt)/Pt = Et∫(1/Rt, t+τ)st+τdτ (1)

Equation (1) expresses the monetary, Mt, and debt, Bt, liabilities of the government, divided by the price level, Pt, in terms of the expected value discounted by the ex-post rate on government debt, Rt, t+τ, of the future primary surpluses st+τ, which are equal to Tt+τ – Gt+τ or difference between taxes, T, and government expenditures, G. Cochrane (2010A) provides the link to a web appendix demonstrating that it is possible to discount by the ex post Rt, t+τ. Expectations by investors of future primary balances of indebted governments may be less optimistic than those in Table I-4 because of government revenues constrained by low growth and government expenditures rigid because of entitlements. Political realities may also jeopardize structural reforms and fiscal austerity.

Table I-4, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of General Government Primary Net Lending/Borrowing as Percent of GDP

| % GDP 2014 | % GDP 2015 | % GDP 2016 | % GDP 2017 | % GDP 2018 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -2.0 | -1.5 | -1.9 | -1.8 | -1.4 |

| Canada | 0.0 | -0.6 | -2.0 | -2.0 | -1.9 |

| France | -1.9 | -1.6 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.2 |

| DE | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Italy | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Japan | -5.6 | -4.9 | -5.2 | -5.3 | -4.7 |

| UK | -3.8 | -2.8 | -1.6 | -1.0 | -0.4 |

| US | -2.2 | -1.5 | -2.1 | -1.8 | -1.3 |

| Euro Area | -0.2 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| DE | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| France | -1.9 | -1.6 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.2 |

| Italy | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| POT | -2.8 | -0.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Ireland | -0.3 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Greece | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Spain | -2.9 | -2.4 | -2.0 | -0.8 | -0.5 |

| EMDE | -0.9 | -2.7 | -2.9 | -2.4 | -1.7 |

| Brazil | -0.6 | -1.9 | -2.8 | -2.2 | -1.2 |

| Russia | -0.7 | -3.2 | -3.4 | -0.8 | 0.1 |

| India | -2.8 | -2.3 | -2.1 | -2.1 | -1.8 |

| China | -0.4 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.3 | -1.7 |

*General Government Net Lending/Borrowing

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The database of the World Economic Outlook of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx) is used to obtain government net lending/borrowing as percent of GDP in Table I-5. Interest on government debt is added to the primary balance to obtain overall government fiscal balance in Table I-5. For highly indebted countries there is an even tougher challenge of fiscal consolidation. Adverse expectations on the success of fiscal consolidation may drive up yields on government securities that could create hurdles to adjustment, growth and employment.

Table I-5, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of General Government Net Lending/Borrowing as Percent of GDP

| % GDP 2014 | % GDP 2015 | % GDP 2016 | % GDP 2017 | % GDP 2018 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -3.8 | -3.2 | -3.6 | -3.3 | -2.8 |

| Canada | -0.5 | -1.3 | -2.5 | -2.3 | -2.0 |

| France | -4.0 | -3.5 | -3.4 | -3.0 | -2.7 |

| DE | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Italy | -3.0 | -2.6 | -2.5 | -2.2 | -1.3 |

| Japan | -6.2 | -5.2 | -5.2 | -5.1 | -4.4 |

| UK | -5.6 | -4.2 | -3.3 | -2.7 | -2.2 |

| US | -4.2 | -3.5 | -4.1 | -3.7 | -3.3 |

| Euro Area | -2.6 | -2.1 | -2.0 | -1.7 | -1.4 |

| DE | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| France | -4.0 | -3.5 | -3.4 | -3.0 | -2.7 |

| Italy | -3.0 | -2.6 | -2.5 | -2.2 | -1.3 |

| POT | -7.2 | -4.4 | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.9 |

| Ireland | -3.7 | -1.9 | -0.7 | -0.5 | -0.3 |

| Greece | -4.1 | -3.1 | -3.4 | -2.7 | -1.7 |

| Spain | -5.9 | -5.1 | -4.5 | -3.1 | -2.7 |

| EMDE | -2.5 | -4.5 | -4.7 | -4.4 | -3.8 |

| Brazil | -6.0 | -10.3 | -10.4 | -9.1 | -8.0 |

| Russia | -1.1 | -3.5 | -3.9 | -1.5 | -0.8 |

| India | -7.3 | -6.9 | -6.7 | -6.6 | -6.2 |

| China | -0.9 | -2.7 | -3.0 | -3.3 | -3.0 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

There were some hopes that the sharp contraction of output during the global recession would eliminate current account imbalances. Table I-6 constructed with the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx) shows that external imbalances have been maintained in the form of current account deficits and surpluses. China’s current account surplus is 2.6 percent of GDP for 2014 and is projected to stabilize at 1.4 percent of GDP in 2018. At the same time, the current account deficit of the US is 2.3 percent of GDP in 2015 and is projected at 2.8 percent of GDP in 2018. The current account surplus of Germany is 7.3 percent for 2014 and remains at a high 7.7 percent of GDP in 2018. Japan’s current account surplus is 0.8 percent of GDP in 2015 and increases to 3.3 percent of GDP in 2018.

Table I-6, IMF World Economic Outlook Databank Projections, Current Account of Balance of Payments as Percent of GDP

| % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -0.7 | -0.6 | -0.5 | -0.5 | -0.6 |

| Canada | -2.3 | -3.2 | -3.7 | -3.1 | -2.8 |

| France | -1.1 | -0.2 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.3 |

| DE | 7.3 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.7 |

| Italy | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Japan | 0.8 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| UK | -4.7 | -5.4 | -5.9 | -4.3 | -3.9 |

| US | -2.3 | -2.6 | -2.5 | -2.7 | -2.8 |

| Euro Area | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 |

| DE | 7.3 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.7 |

| France | -1.1 | -0.2 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.3 |

| Italy | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| POT | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | -0.7 | -0.8 |

| Ireland | 1.7 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 8.8 |

| Greece | -2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Spain | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| EMDE | 0.6 | -0.1 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.5 |

| Brazil | -4.3 | -3.3 | -0.8 | -1.3 | -1.5 |

| Russia | 2.8 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 3.9 |

| India | -1.3 | -1.1 | -1.4 | -2.0 | -2.2 |

| China | 2.6 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The G7 meeting in Washington on Apr 21 2006 of finance ministers and heads of central bank governors of the G7 established the “doctrine of shared responsibility” (G7 2006Apr):

“We, Ministers and Governors, reviewed a strategy for addressing global imbalances. We recognized that global imbalances are the product of a wide array of macroeconomic and microeconomic forces throughout the world economy that affect public and private sector saving and investment decisions. We reaffirmed our view that the adjustment of global imbalances:

- Is shared responsibility and requires participation by all regions in this global process;

- Will importantly entail the medium-term evolution of private saving and investment across countries as well as counterpart shifts in global capital flows; and

- Is best accomplished in a way that maximizes sustained growth, which requires strengthening policies and removing distortions to the adjustment process.

In this light, we reaffirmed our commitment to take vigorous action to address imbalances. We agreed that progress has been, and is being, made. The policies listed below not only would be helpful in addressing imbalances, but are more generally important to foster economic growth.

- In the United States, further action is needed to boost national saving by continuing fiscal consolidation, addressing entitlement spending, and raising private saving.

- In Europe, further action is needed to implement structural reforms for labor market, product, and services market flexibility, and to encourage domestic demand led growth.

- In Japan, further action is needed to ensure the recovery with fiscal soundness and long-term growth through structural reforms.

Others will play a critical role as part of the multilateral adjustment process.

- In emerging Asia, particularly China, greater flexibility in exchange rates is critical to allow necessary appreciations, as is strengthening domestic demand, lessening reliance on export-led growth strategies, and actions to strengthen financial sectors.

- In oil-producing countries, accelerated investment in capacity, increased economic diversification, enhanced exchange rate flexibility in some cases.

- Other current account surplus countries should encourage domestic consumption and investment, increase micro-economic flexibility and improve investment climates.

We recognized the important contribution that the IMF can make to multilateral surveillance.”

The concern at that time was that fiscal and current account global imbalances could result in disorderly correction with sharp devaluation of the dollar after an increase in premiums on yields of US Treasury debt (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007)). The IMF was entrusted with monitoring and coordinating action to resolve global imbalances. The G7 was eventually broadened to the formal G20 in the effort to coordinate policies of countries with external surpluses and deficits.

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx) is used to construct Table I-7 with fiscal and current account imbalances projected for 2016 and 2018. The WEO finds the need to rebalance external and domestic demand (IMF 2011WEOSep xvii):

“Progress on this front has become even more important to sustain global growth. Some emerging market economies are contributing more domestic demand than is desirable (for example, several economies in Latin America); others are not contributing enough (for example, key economies in emerging Asia). The first set needs to restrain strong domestic demand by considerably reducing structural fiscal deficits and, in some cases, by further removing monetary accommodation. The second set of economies needs significant currency appreciation alongside structural reforms to reduce high surpluses of savings over investment. Such policies would help improve their resilience to shocks originating in the advanced economies as well as their medium-term growth potential.”

The IMF (2012WEOApr, XVII) explains decreasing importance of the issue of global imbalances as follows:

“The latest developments suggest that global current account imbalances are no longer expected to widen again, following their sharp reduction during the Great Recession. This is largely because the excessive consumption growth that characterized economies that ran large external deficits prior to the crisis has been wrung out and has not been offset by stronger consumption in .surplus economies. Accordingly, the global economy has experienced a loss of demand and growth in all regions relative to the boom years just before the crisis. Rebalancing activity in key surplus economies toward higher consumption, supported by more market-determined exchange rates, would help strengthen their prospects as well as those of the rest of the world.”

The IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/02/pdf/c4.pdf) analyzes global imbalances as:

- Global current account imbalances have narrowed by more than a third from

their peak in 2006. Key imbalances—the large deficit of the United States and

the large surpluses of China and Japan—have more than halved.

- The narrowing in imbalances has largely been driven by demand contraction

(“expenditure reduction”) in deficit economies.

- Exchange rate adjustment has facilitated rebalancing in China and the United

States, but in general the contribution of exchange rate changes (“expenditure

switching”) to current account adjustment has been relatively modest.

- The narrowing of imbalances is expected to be durable, as domestic demand in

deficit economies is projected to remain well below pre-crisis trends.

- Since flow imbalances have narrowed but not reversed, net creditor and debtor

positions have widened further. Weak growth has also contributed to still high

ratios of net external liabilities to GDP in some debtor economies.

- Risks of a disruptive adjustment in global current account balances have

decreased, but global demand rebalancing remains a policy priority. Stronger

external demand will be instrumental for reviving growth in debtor countries and

reducing their net external liabilities.”

Table I-7, Fiscal Deficit, Current Account Deficit and Government Debt as % of GDP and 2015 Dollar GDP

| GDP 2016 | FD | CAD | Debt | FD%GDP | CAD%GDP | Debt | |

| US | 18562 | -2.1 | -2.5 | 82.2 | -1.3 | -2.8 | 82.1 |

| Japan | 4730 | -5.2 | 3.7 | 127.9 | -4.7 | 3.3 | 132.6 |

| UK | 2650 | -1.6 | -5.9 | 80.5 | -0.4 | -3.9 | 80.0 |

| Euro | 11991 | -0.1 | 3.4 | 67.4 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 66.2 |

| Ger | 3495 | 1.2 | 8.6 | 45.4 | 0.9 | 7.7 | 42.0 |

| France | 2488 | -1.5 | -0.5 | 89.2 | -1.2 | -0.3 | 90.0 |

| Italy | 1853 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 113.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 112.7 |

| Can | 1532 | -2.0 | -3.7 | 26.9 | -1.9 | -2.8 | 23.6 |

| China | 11392 | -2.2 | 2.4 | 46.3 | -1.7 | 1.4 | 52.6 |

| Brazil | 1770 | -2.8 | -0.8 | 45.8 | -1.2 | -1.5 | 53.6 |

Note: GER = Germany; Can = Canada; FD = fiscal deficit; CAD = current account deficit

FD is primary except total for China; Debt is net except gross for China

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

Brazil faced in the debt crisis of 1982 a more complex policy mix. Between 1977 and 1983, Brazil’s terms of trade, export prices relative to import prices, deteriorated 47 percent and 36 percent excluding oil (Pelaez 1987, 176-79; Pelaez 1986, 37-66; see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 178-87). Brazil had accumulated unsustainable foreign debt by borrowing to finance balance of payments deficits during the 1970s. Foreign lending virtually stopped. The German mark devalued strongly relative to the dollar such that Brazil’s products lost competitiveness in Germany and in multiple markets in competition with Germany. The resolution of the crisis was devaluation of the Brazilian currency by 30 percent relative to the dollar and subsequent maintenance of parity by monthly devaluation equal to inflation and indexing that resulted in financial stability by parity in external and internal interest rates avoiding capital flight. With a combination of declining imports, domestic import substitution and export growth, Brazil followed rapid growth in the US and grew out of the crisis with surprising GDP growth of 4.5 percent in 1984.

The euro zone faces a critical survival risk because several of its members may default on their sovereign obligations if not bailed out by the other members. The valuation equation of bonds is essential to understanding the stability of the euro area. An explanation is provided in this paragraph and readers interested in technical details are referred to the Subsection IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation. Contrary to the Wriston doctrine, investing in sovereign obligations is a credit decision. The value of a bond today is equal to the discounted value of future obligations of interest and principal until maturity. On Dec 30, 2011, the yield of the 2-year bond of the government of Greece was quoted around 100 percent. In contrast, the 2-year US Treasury note traded at 0.239 percent and the 10-year at 2.871 percent while the comparable 2-year government bond of Germany traded at 0.14 percent and the 10-year government bond of Germany traded at 1.83 percent. There is no need for sovereign ratings: the perceptions of investors are of relatively higher probability of default by Greece, defying Wriston (1982), and nil probability of default of the US Treasury and the German government. The essence of the sovereign credit decision is whether the sovereign will be able to finance new debt and refinance existing debt without interrupting service of interest and principal. Prices of sovereign bonds incorporate multiple anticipations such as inflation and liquidity premiums of long-term relative to short-term debt but also risk premiums on whether the sovereign’s debt can be managed as it increases without bound. The austerity measures of Italy are designed to increase the primary surplus, or government revenues less expenditures excluding interest, to ensure investors that Italy will have the fiscal strength to manage its debt exceeding 100 percent of GDP, which is the third largest in the world after the US and Japan. Appendix IIIE links the expectations on the primary surplus to the real current value of government monetary and fiscal obligations. As Blanchard (2011SepWEO) analyzes, fiscal consolidation to increase the primary surplus is facilitated by growth of the economy. Italy and the other indebted sovereigns in Europe face the dual challenge of increasing primary surpluses while maintaining growth of the economy (for the experience of Brazil in the debt crisis of 1982 see Pelaez 1986, 1987).

Much of the analysis and concern over the euro zone centers on the lack of credibility of the debt of a few countries while there is credibility of the debt of the euro zone as a whole. In practice, there is convergence in valuations and concerns toward the fact that there may not be credibility of the euro zone as a whole. The fluctuations of financial risk assets of members of the euro zone move together with risk aversion toward the countries with lack of debt credibility. This movement raises the need to consider analytically sovereign debt valuation of the euro zone as a whole in the essential analysis of whether the single-currency will survive without major changes.

Welfare economics considers the desirability of alternative states, which in this case would be evaluating the “value” of Germany (1) within and (2) outside the euro zone. Is the sum of the wealth of euro zone countries outside of the euro zone higher than the wealth of these countries maintaining the euro zone? On the choice of indicator of welfare, Hicks (1975, 324) argues:

“Partly as a result of the Keynesian revolution, but more (perhaps) because of statistical labours that were initially quite independent of it, the Social Product has now come right back into its old place. Modern economics—especially modern applied economics—is centered upon the Social Product, the Wealth of Nations, as it was in the days of Smith and Ricardo, but as it was not in the time that came between. So if modern theory is to be effective, if it is to deal with the questions which we in our time want to have answered, the size and growth of the Social Product are among the chief things with which it must concern itself. It is of course the objective Social Product on which attention must be fixed. We have indexes of production; we do not have—it is clear we cannot have—an Index of Welfare.”

If the burden of the debt of the euro zone falls on Germany and France or only on Germany, is the wealth of Germany and France or only Germany higher after breakup of the euro zone or if maintaining the euro zone? In practice, political realities will determine the decision through elections.

The prospects of survival of the euro zone are dire. Table I-8 is constructed with IMF World Economic Outlook database (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx) for GDP in USD billions, primary net lending/borrowing as percent of GDP and general government debt as percent of GDP for selected regions and countries in 2016.

Table I-8, World and Selected Regional and Country GDP and Fiscal Situation

| GDP 2016 | Primary Net Lending Borrowing | General Government Net Debt | |

| World | 75,213 | ||

| Euro Zone | 11,991 | -0.1 | 67.4 |

| Portugal | 206 | 1.3 | 121.9 |

| Ireland | 308 | 1.3 | 63.8 |

| Greece | 195 | -3.4 | 183.4** |

| Spain | 1,252 | -2.0 | 81.4 |

| Major Advanced Economies G7 | 35,310 | -1.9 | 84.3 |

| United States | 18,562 | -2.1 | 82.2 |

| UK | 2,650 | -1.6 | 80.5 |

| Germany | 3,495 | 1.2 | 45.4 |

| France | 2,488 | -1.5 | 89.2 |

| Japan | 4,730 | -5.2 | 127.9 |

| Canada | 1,532 | -2.0 | 26.9 |

| Italy | 1,852 | 1.3 | 113.8 |

| China | 11,392 | -2.2 | 46.3*** |

*Net Lending/borrowing**Gross Debt

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

The data in Table I-8 are used for some very simple calculations in Table I-9. The column “Net Debt USD Billions 2016” in Table I-9 is generated by applying the percentage in Table I-8 column “General Government Net Debt % GDP 2016” to the column “GDP 2016 USD Billions.” The total debt of France and Germany in 2016 is $3806.0 billion, as shown in row “B+C” in column “Net Debt USD Billions 2016.” The sum of the debt of Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland is $3391.9 billion, adding rows D+E+F+G+H in column “Net Debt USD billions 2016.” There is some simple “unpleasant bond arithmetic” in the two final columns of Table I-9. Suppose the entire debt burdens of the five countries with probability of default were to be guaranteed by France and Germany, which de facto would be required by continuing the euro zone. The sum of the total debt of these five countries and the debt of France and Germany is shown in column “Debt as % of Germany plus France GDP” to reach $7197.9 billion, which would be equivalent to 120.3 percent of their combined GDP in 2016. Under this arrangement, the entire debt of selected members of the euro zone including debt of France and Germany would not have nil probability of default. The final column provides “Debt as % of Germany GDP” that would exceed 205.9 percent if including debt of France and 142.4 percent of German GDP if excluding French debt. The unpleasant bond arithmetic illustrates that there is a limit as to how far Germany and France can go in bailing out the countries with unsustainable sovereign debt without incurring severe pains of their own such as downgrades of their sovereign credit ratings. A central bank is not typically engaged in direct credit because of remembrance of inflation and abuse in the past. There is also a limit to operations of the European Central Bank in doubtful credit obligations. Wriston (1982) would prove to be wrong again that countries do not bankrupt but would have a consolation prize that similar to LBOs the sum of the individual values of euro zone members outside the current agreement exceeds the value of the whole euro zone. Internal rescues of French and German banks may be less costly than bailing out other euro zone countries so that they do not default on French and German banks. Analysis of fiscal stress is quite difficult without including another global recession in an economic cycle that is already mature by historical experience.

Table I-9, Guarantees of Debt of Sovereigns in Euro Area as Percent of GDP of Germany and France, USD Billions and %

| Net Debt USD Billions 2016 | Debt as % of Germany Plus France GDP | Debt as % of Germany GDP | |

| A Euro Area | 8,081.9 | ||

| B Germany | 1,586.7 | $7197.9 as % of $3495 =205.9% $4978.6 as % of $3495 =142.4% | |

| C France | 2,219.3 | ||

| B+C | 3,806.0 | GDP $5983 Total Debt $7,197.9 Debt/GDP: 120.3% | |

| D Italy | 2,107.6 | ||

| E Spain | 1,019.1 | ||

| F Portugal | 251.1 | ||

| G Greece | 357.6 | ||

| H Ireland | 196.5 | ||

| Subtotal D+E+F+G+H | 3,391.9 |

Source: calculation with IMF data IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

World trade projections of the IMF are in Table I-10. There is decreasing growth of the volume of world trade of goods and services from 2.6 percent in 2015 to 2.3 percent in 2016, increasing to 3.8 percent in 2017. Growth improves to 4.1 percent on average from 2017 to 2021. World trade would be slower for advanced economies while emerging and developing economies (EMDE) experience faster growth. World economic slowdown would be more challenging with lower growth of world trade.

Table I-10, IMF, Projections of World Trade, USD Billions, USD/Barrel and Annual ∆%

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average ∆% 2017-2021 | |

| World Trade Volume (Goods and Services) | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 |

| Exports Goods & Services | 2.7 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Imports Goods & Services | 2.4 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| Average Oil Price USD/Barrel | 50.79 | 42.96 | 50.64 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 79.16 |

| Average Annual ∆% Export Unit Value of Manufactures | -2.9 | -2.1 | 1.4 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 0.4 |

| Exports of Goods & Services | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average ∆% 2008-2017 |

| EMDE | 1.3 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| G7 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| Imports Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -0.6 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

| G7 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods & Services | ||||

| EMDE | -4.1 | -1.0 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| G7 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods | ||||

| EMDE | -4.0 | -1.0 | 0.1 | -0.1 |

| G7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

Notes: Commodity Price Index includes Fuel and Non-fuel Prices; Commodity Industrial Inputs Price includes agricultural raw materials and metal prices; Oil price is average of WTI, Brent and Dubai

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/index.aspx

I Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels increased by only 4 percent from Jan 2009 to Jan 2012. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job in early 2012 is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer in the American Economic Review (Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 2012May) on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar amount of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn, there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (Section II and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rate-uncertainty-and-valuation.html). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled. There are four subsections. IA1 Hiring Collapse provides the data and analysis on the weakness of hiring in the United States economy. IA2 Labor Underutilization provides the measures of labor underutilization of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Statistics on the decline of full-time employment are in IA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment provides the data on high unemployment of ages 16 to 24 years and of ages 45 years or over.

IA1 Hiring Collapse. An important characteristic of the current fractured labor market of the US is the closing of the avenue for exiting unemployment and underemployment normally available through dynamic hiring. Another avenue that is closed is the opportunity for advancement in moving to new jobs that pay better salaries and benefits again because of the collapse of hiring in the United States. Those who are unemployed or underemployed cannot find a new job even accepting lower wages and no benefits. The employed cannot escape declining inflation-adjusted earnings because there is no hiring. The objective of this section is to analyze hiring and labor underutilization in the United States.

Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53 consider an appropriate measure of job stress:

“The right measure of the state of the labor market is the exit rate from unemployment, defined as the number of hires divided by the number unemployed, rather than the unemployment rate itself. What matters to the unemployed is not how many of them there are, but how many of them there are in relation to the number of hires by firms.”

The natural rate of unemployment and the similar NAIRU are quite difficult to estimate in practice (Ibid; see Ball and Mankiw 2002).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) created the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) with the purpose that (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/jltover.htm#purpose):

“These data serve as demand-side indicators of labor shortages at the national level. Prior to JOLTS, there was no economic indicator of the unmet demand for labor with which to assess the presence or extent of labor shortages in the United States. The availability of unfilled jobs—the jobs opening rate—is an important measure of tightness of job markets, parallel to existing measures of unemployment.”

The BLS collects data from about 16,000 US business establishments in nonagricultural industries through the 50 states and DC. The data are released monthly and constitute an important complement to other data provided by the BLS (see also Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 6-7).

There is socio-economic stress in the combination of adverse events and cyclical performance:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources with GDP two trillion dollars below trend (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/and-as-ever-economic-outlook-is.html). US GDP grew at the average rate of 3.2 percent per year from 1929 to 2015, with similar performance in whole cycles of contractions and expansions, but only at 1.2 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2015. GDP in IIQ2016 is 14.0 percent lower than what it would have been had it grown at trend of 3.0 percent

- Private fixed investment stagnating at increase of 7.4 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2016 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/and-as-ever-economic-outlook-is.html)

- Twenty four million or 14.0 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/fluctuating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-with-exchange-rate.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/turbulence-of-financial-asset.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets-in.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (Section II and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rate-uncertainty-and-valuation.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/contraction-of-united-states-corporate.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/subdued-foreign-growth-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-volatile_17.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-policy-conundrum-recovery.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/impact-of-monetary-policy-on-exchange.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/volatility-of-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/dollar-revaluation-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-exchange-rate-struggle-recovery.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/g20-monetary-policy-recovery-without.html)

- Productivity growth fell from 2.2 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2015 and average 2.3 percent per year from 1947 to 2007 to 1.3 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2015, deteriorating future growth and prosperity (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/rising-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/considerable-uncertainty-about-economic.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-fed-funds-rate-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/quite-high-equity-valuations-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/financial-risks-twenty-six-million.html)

- Output of manufacturing in Aug 2016 at 25.8 percent below long-term trend since 1919 and at 19.2 percent below trend since 1986 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/unconventional-monetary-policy-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/exchange-rate-and-financial-asset.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/fluctuating-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-reducing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/oscillating-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/contracting-united-states-industrial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/interest-rate-policy-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/competitive-currency-conflicts-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins of production across countries in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-volatility-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/unresolved-us-balance-of-payments.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/fomc-projections-world-inflation-waves.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/most-fomc-participants-judged-that-if.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html and earlier) (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-competitive.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/02/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/uncertainty-of-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/interest-rate-liftoff-followed-by.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-quagmire-world.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-increase-on-hold-because.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/global-decline-of-values-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/07/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/global-portfolio-reallocations-squeeze.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/world-financial-turbulence-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/exchange-rate-conflicts-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/patience-on-interest-rate-increases.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/squeeze-of-economic-activity-by-carry.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/imf-view-squeeze-of-economic-activity.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/global-competitive-easing-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/07/financial-asset-values-rebound-from.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/financial-turbulence-twenty-four.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/04/proceeding-cautiously-in-monetary.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/twenty-five-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/closely-monitoring-global-economic-and.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/dollar-revaluation-and-decreasing.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/dollar-revaluation-constraining.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/11/live-possibility-of-interest-rates.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/labor-market-uncertainty-and-interest.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/interest-rate-policy-dependent-on-what.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/08/fluctuating-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/international-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/higher-volatility-of-asset-prices-at.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/dollar-devaluation-and-carry-trade.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/04/volatility-of-valuations-of-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/global-competitive-devaluation-rules.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/job-creation-and-monetary-policy-twenty.html and earlier (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/11/growth-uncertainties-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html)

- 43 million in poverty and 29 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1999 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/10/interest-rate-policy-uncertainty-imf.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by 16.7 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2016 when it would have grown over 29.6 percent at trend of 3.1 percent per year in real terms from IVQ1945 to IIQ2016 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-economic-outlook-is-inherently.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/06/of-course-considerable-uncertainty.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/03/monetary-policy-and-fluctuations-of_13.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/dollar-revaluation-and-financial-risk.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/12/valuations-of-risk-financial-assets.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/financial-indecision-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/global-financial-risks-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html). Financial assets increased $19.5 trillion while nonfinancial assets increased $3.3 trillion with likely concentration of wealth in those with access to sophisticated financial investments. Real estate assets adjusted for inflation fell 4.1 percent.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) revised on Mar 17, 2016 “With the release of January 2016 data on March 17, job openings, hires, and separations data have been revised from December 2000 forward to incorporate annual updates to the Current Employment Statistics employment estimates and the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) seasonal adjustment factors. In addition, all data series are now available on a seasonally adjusted basis. Tables showing the revisions from 2000 through 2015 can be found using this link:http://www.bls.gov/jlt/revisiontables.htm.” (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/). Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 63.491 million in 2006 to 61.680 million in 2015 or by 1.811 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 59.206 million in 2006 to 57.557 million in 2015 or by 1.649 million, as shown in Table I-1. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) has fallen from 47.1 in 2005 to 43.5 in 2015 and in the private sector (RHP) from 52.8 in 2005 to 48.0 in 2015. Hiring has not recovered as in previous cyclical expansions because of the low rate of economic growth in the current cyclical expansion. The civilian noninstitutional population or those in condition to work increased from 228.815 million in 2006 to 250.801 million in 2015 or by 21.986 million. Hiring has not recovered prerecession levels while needs of hiring multiplied because of growth of population by more than 21 million. Private hiring of 59.206 million in 2006 was equivalent to 25.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 228.815, or those in condition of working, falling to 57.557 million in 2015 or 22.9 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population of 250.801 million in 2015. The percentage of hiring in civilian noninstitutional population of 25.9 percent in 2006 would correspond to 64.957 million of hiring in 2015, which would be 7.400 million higher than actual 57.557 million in 2015. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.1 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 28 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2016. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the third estimate of GDP for IIQ2016 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2016/pdf/gdp2q16_3rd.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,745.9 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,355.6 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,745.9/$14,355.6 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/and-as-ever-economic-outlook-is.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1988, 4.8 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1989, 4.7 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1989, 4.5 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1989 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/mediocre-cyclical-united-states.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/08/and-as-ever-economic-outlook-is.html). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2016 would have accumulated to 28.6 percent. GDP in IIQ2016 would be $19,279.5 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2696.4 billion than actual $16,583.1 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 23.6 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment/underemployment of 14.0 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/10/twenty-four-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/09/interest-rates-and-valuations-of-risk.html). US GDP in IIQ2016 is 14.0 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,583.1 billion in IIQ2016 or 10.6 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent. Professor John H. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. Cochrane (2016May02) measures GDP growth in the US at average 3.5 percent per year from 1950 to 2000 and only at 1.76 percent per year from 2000 to 2015 with only at 2.0 percent annual equivalent in the current expansion. Cochrane (2016May02) proposes drastic changes in regulation and legal obstacles to private economic activity. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. There is classic research on analyzing deviations of output from trend (see for example Schumpeter 1939, Hicks 1950, Lucas 1975, Sargent and Sims 1977). The long-term trend is growth of manufacturing at average 3.1 percent per year from Aug 1919 to Aug 2016. Growth at 3.1 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 108.2316 in Dec 2007 to 141.0258 in Aug 2016. The actual index NSA in Aug 2016 is 104.6251, which is 27.6 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.1 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2015. Using trend growth of 2.1 percent per year, the index would increase to 129.5532 in Aug 2016. The output of manufacturing at 104.6251 in Aug 2016 is 19.2 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table I-1, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in Thousands and Percentage of Total Employment

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 | 62,727 | 47.5 | 58,616 | 52.8 |

| 2002 | 58,416 | 44.7 | 54,592 | 50.0 |

| 2003 | 56,919 | 43.7 | 53,529 | 49.2 |

| 2004 | 60,236 | 45.7 | 56,567 | 51.3 |

| 2005 | 63,089 | 47.1 | 59,298 | 52.8 |

| 2006 | 63,491 | 46.5 | 59,206 | 51.7 |

| 2007 | 62,239 | 45.1 | 57,816 | 49.9 |

| 2008 | 54,764 | 39.9 | 51,260 | 44.7 |

| 2009 | 46,190 | 35.2 | 42,882 | 39.4 |

| 2010 | 48,659 | 37.3 | 44,831 | 41.6 |

| 2011 | 50,253 | 38.1 | 47,166 | 42.9 |

| 2012 | 52,354 | 39.0 | 48,914 | 43.6 |

| 2013 | 54,318 | 39.8 | 50,879 | 44.4 |

| 2014 | 58,632 | 42.2 | 54,980 | 47.0 |

| 2015 | 61,680 | 43.5 | 57,557 | 48.0 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

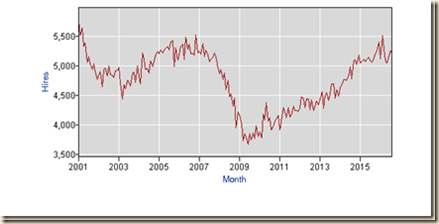

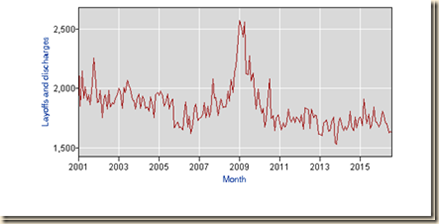

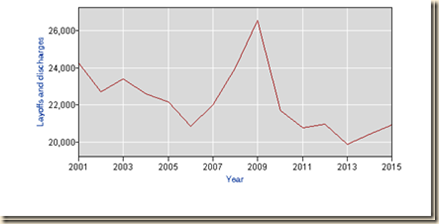

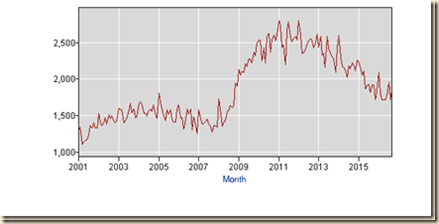

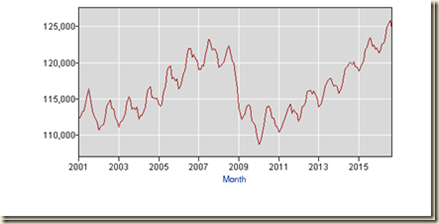

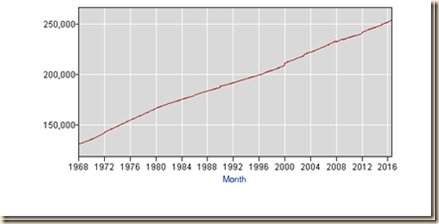

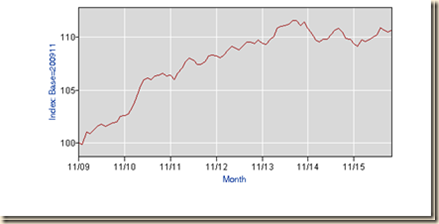

Chart I-1 shows the annual level of total nonfarm hiring (HNF) that collapsed during the global recession after 2007 in contrast with milder decline in the shallow recession of 2001. Nonfarm hiring has not recovered, remaining at a depressed level. The civilian noninstitutional population or those in condition to work increased from 228.815 million in 2006 to 250.801 million in 2015 or by 21.986 million. Hiring has not recovered precession levels while needs of hiring multiplied because of growth of population by more than 21 million.

Chart I-1, US, Level Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), Annual, 2001-2015

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics