Unconventional Monetary Policy and Valuations of Risk Financial Assets, Recovery without Hiring, United States Industrial Production, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016

IA Unconventional Monetary Policy and Valuations of Risk Financial Assets

I Recovery without Hiring

IA1 Hiring Collapse

IA2 Labor Underutilization

ICA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and

Middle-Age Unemployment

IIB United States Industrial Production

II IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

IA Unconventional Monetary Policy and Valuations of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with fluctuating volumes. For example, the DJIA has increased 65.1 percent since the trough of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe on Jul 2, 2010 to Jan 15, 2016; S&P 500 has gained 83.9 percent and DAX 68.3 percent. The overwhelming risk factor is the unsustainable Treasury deficit/debt of the United States (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/09/monetary-policy-designed-on-measurable.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/06/fluctuating-financial-asset-valuations.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/impatience-with-monetary-policy-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/03/irrational-exuberance-mediocre-cyclical.html). A competing event is the high level of valuations of risk financial assets (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/01/peaking-valuations-of-risk-financial.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html). Matt Jarzemsky, writing on “Dow industrials set record,” on Mar 5, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324156204578275560657416332.html), analyzes that the DJIA broke the closing high of 14,164.53 set on Oct 9, 2007, and subsequently also broke the intraday high of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. The DJIA closed at 15,988.08 on Fri Jul 15, 2016, which is higher by 12.9 percent than the value of 14,164.53 reached on Oct 9, 2007 and higher by 12.6 percent than the value of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. Values of risk financial assets have been approaching or exceeding historical highs.

The financial crisis and global recession were caused by interest rate and housing subsidies and affordability policies that encouraged high leverage and risks, low liquidity and unsound credit (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 157-66, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 217-27, International Financial Architecture (2005), 15-18, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II (2008b), 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 182-4). Several past comments of this blog elaborate on these arguments, among which: http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/professor-mckinnons-bubble-economy.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/world-inflation-quantitative-easing.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/treasury-yields-valuation-of-risk.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/11/quantitative-easing-theory-evidence-and.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html

Table VI-1 shows the phenomenal impulse to valuations of risk financial assets originating in the initial shock of near zero interest rates in 2003-2004 with the fed funds rate at 1 percent, in fear of deflation that never materialized, and quantitative easing in the form of suspension of the auction of 30-year Treasury bonds to lower mortgage rates. World financial markets were dominated by monetary and housing policies in the US. Between 2002 and 2008, the DJ UBS Commodity Index rose 165.5 percent largely because of unconventional monetary policy encouraging carry trades from low US interest rates to long leveraged positions in commodities, exchange rates and other risk financial assets. The charts of risk financial assets show sharp increase in valuations leading to the financial crisis and then profound drops that are captured in Table VI-1 by percentage changes of peaks and troughs. The first round of quantitative easing and near zero interest rates depreciated the dollar relative to the euro by 39.3 percent between 2003 and 2008, with revaluation of the dollar by 25.1 percent from 2008 to 2010 in the flight to dollar-denominated assets in fear of world financial risks. The dollar revalued 8.4 percent by Fri Jan 15, 2016. Dollar devaluation is a major vehicle of monetary policy in reducing the output gap that is implemented in the probably erroneous belief that devaluation will not accelerate inflation, misallocating resources toward less productive economic activities and disrupting financial markets. The last row of Table VI-1 shows CPI inflation in the US rising from 1.9 percent in 2003 to 4.1 percent in 2007 even as monetary policy increased the fed funds rate from 1 percent in Jun 2004 to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006.

Table VI-1, Volatility of Assets

| DJIA | 10/08/02-10/01/07 | 10/01/07-3/4/09 | 3/4/09- 4/6/10 | |

| ∆% | 87.8 | -51.2 | 60.3 | |

| NYSE Financial | 1/15/04- 6/13/07 | 6/13/07- 3/4/09 | 3/4/09- 4/16/07 | |

| ∆% | 42.3 | -75.9 | 121.1 | |

| Shanghai Composite | 6/10/05- 10/15/07 | 10/15/07- 10/30/08 | 10/30/08- 7/30/09 | |

| ∆% | 444.2 | -70.8 | 85.3 | |

| STOXX EUROPE 50 | 3/10/03- 7/25/07 | 7/25/07- 3/9/09 | 3/9/09- 4/21/10 | |

| ∆% | 93.5 | -57.9 | 64.3 | |

| UBS Com. | 1/23/02- 7/1/08 | 7/1/08- 2/23/09 | 2/23/09- 1/6/10 | |

| ∆% | 165.5 | -56.4 | 41.4 | |

| 10-Year Treasury | 6/10/03 | 6/12/07 | 12/31/08 | 4/5/10 |

| % | 3.112 | 5.297 | 2.247 | 3.986 |

| USD/EUR | 6/26/03 | 7/14/08 | 6/07/10 | 01/15/2016 |

| Rate | 1.1423 | 1.5914 | 1.192 | 1.0917 |

| CNY/USD | 01/03 | 07/21 | 7/15 | 01/15/ 2016 |

| Rate | 8.2798 | 8.2765 | 6.8211 | 6.5836 |

| New House | 1963 | 1977 | 2005 | 2009 |

| Sales 1000s | 560 | 819 | 1283 | 375 |

| New House | 2000 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 |

| Median Price $1000 | 169 | 247 | 217 | 203 |

| 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2010 | |

| CPI | 1.9 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 1.5 |

Sources: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://www.census.gov/const/www/newressalesindex_excel.html

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_eu.htm

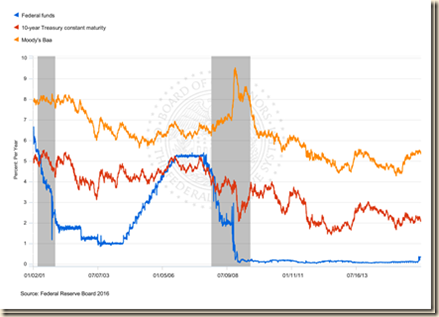

There are collateral effects of unconventional monetary policy. Chart VIII-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate on the overnight fed funds rate and the yields of the 10-year constant maturity Treasury and the Baa seasoned corporate bond. Table VIII-3 provides the data for selected points in Chart VIII-1. There are two important economic and financial events, illustrating the ease of inducing carry trade with extremely low interest rates and the resulting financial crash and recession of abandoning extremely low interest rates.

- The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target of the fed funds rate from 7.03 percent on Jul 3, 2000, to 1.00 percent on Jun 22, 2004, in pursuit of non-existing deflation (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-85). Central bank commitment to maintain the fed funds rate at 1.00 percent induced adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMS) linked to the fed funds rate. Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment. The exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at interest rates close to zero, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV). The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper with the objective of purchasing default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever-increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and worked with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity by the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions. The put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4). The FOMC implemented increments of 25 basis points of the fed funds target from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006, raising the fed funds rate to 5.25 percent on Jul 3, 2006, as shown in Chart VIII-1. The gradual exit from the first round of unconventional monetary policy from 1.00 percent in Jun 2004 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/monetary/2004/20040630/default.htm) to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20060629a.htm) caused the financial crisis and global recession.

- On Dec 16, 2008, the policy determining committee of the Fed decided (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm): “The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to establish a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent.” Policymakers emphasize frequently that there are tools to exit unconventional monetary policy at the right time. At the confirmation hearing on nomination for Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Vice Chair Yellen (2013Nov14 http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20131114a.htm), states that: “The Federal Reserve is using its monetary policy tools to promote a more robust recovery. A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases. I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.” Perception of withdrawal of $2671 billion, or $2.7 trillion, of bank reserves (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1), would cause Himalayan increase in interest rates that would provoke another recession. There is no painless gradual or sudden exit from zero interest rates because reversal of exposures created on the commitment of zero interest rates forever.

In his classic restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958, 86):

“The assumption that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates and differ from each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969) provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus, g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Friedman 1957). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

Dan Strumpf and Pedro Nicolaci da Costa, writing on “Fed’s Yellen: Stock Valuations ‘Generally are Quite High,’” on May 6, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-yellen-cites-progress-on-bank-regulation-1430918155?tesla=y ), quote Chair Yellen at open conversation with Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, finding “equity-market valuations” as “quite high” with “potential dangers” in bond valuations. The DJIA fell 0.5 percent on May 6, 2015, after the comments and then increased 0.5 percent on May 7, 2015 and 1.5 percent on May 8, 2015.

| Fri May 1 | Mon 4 | Tue 5 | Wed 6 | Thu 7 | Fri 8 |

| DJIA 18024.06 -0.3% 1.0% | 18070.40 0.3% 0.3% | 17928.20 -0.5% -0.8% | 17841.98 -1.0% -0.5% | 17924.06 -0.6% 0.5% | 18191.11 0.9% 1.5% |

There are two approaches in theory considered by Bordo (2012Nov20) and Bordo and Lane (2013). The first approach is in the classical works of Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz (1963a, 1987) and Karl Brunner and Allan H. Meltzer (1973). There is a similar approach in Tobin (1969). Friedman and Schwartz (1963a, 66) trace the effects of expansionary monetary policy into increasing initially financial asset prices: “It seems plausible that both nonbank and bank holders of redundant balances will turn first to securities comparable to those they have sold, say, fixed-interest coupon, low-risk obligations. But as they seek to purchase these they will tend to bid up the prices of those issues. Hence they, and also other holders not involved in the initial central bank open-market transactions, will look farther afield: the banks, to their loans; the nonbank holders, to other categories of securities-higher risk fixed-coupon obligations, equities, real property, and so forth.”

The second approach is by the Austrian School arguing that increases in asset prices can become bubbles if monetary policy allows their financing with bank credit. Professor Michael D. Bordo provides clear thought and empirical evidence on the role of “expansionary monetary policy” in inflating asset prices (Bordo2012Nov20, Bordo and Lane 2013). Bordo and Lane (2013) provide revealing narrative of historical episodes of expansionary monetary policy. Bordo and Lane (2013) conclude that policies of depressing interest rates below the target rate or growth of money above the target influences higher asset prices, using a panel of 18 OECD countries from 1920 to 2011. Bordo (2012Nov20) concludes: “that expansionary money is a significant trigger” and “central banks should follow stable monetary policies…based on well understood and credible monetary rules.” Taylor (2007, 2009) explains the housing boom and financial crisis in terms of expansionary monetary policy. Professor Martin Feldstein (2016), at Harvard University, writing on “A Federal Reserve oblivious to its effects on financial markets,” on Jan 13, 2016, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/a-federal-reserve-oblivious-to-its-effect-on-financial-markets-1452729166), analyzes how unconventional monetary policy drove values of risk financial assets to high levels. Quantitative easing and zero interest rates distorted calculation of risks with resulting vulnerabilities in financial markets.

Another hurdle of exit from zero interest rates is “competitive easing” that Professor Raghuram Rajan, governor of the Reserve Bank of India, characterizes as disguised “competitive devaluation” (http://www.centralbanking.com/central-banking-journal/interview/2358995/raghuram-rajan-on-the-dangers-of-asset-prices-policy-spillovers-and-finance-in-india). The fed has been considering increasing interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) announced, on Mar 5, 2015, the beginning on Mar 9, 2015 of its quantitative easing program denominated as Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP), consisting of “combined monthly purchases of EUR 60 bn [billion] in public and private sector securities” (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/liq/html/pspp.en.html). Expectation of increasing interest rates in the US together with euro rates close to zero or negative cause revaluation of the dollar (or devaluation of the euro and of most currencies worldwide). US corporations suffer currency translation losses of their foreign transactions and investments (http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Pronouncement_C/SummaryPage&cid=900000010318) while the US becomes less competitive in world trade (Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c)). The DJIA fell 1.5 percent on Mar 6, 2015 and the dollar revalued 2.2 percent from Mar 5 to Mar 6, 2015. The euro has devalued 45.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Jan 15, 2016.

| Fri 27 Feb | Mon 3/2 | Tue 3/3 | Wed 3/4 | Thu 3/5 | Fri 3/6 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1197 1.6% 0.0% | 1.1185 0.1% 0.1% | 1.1176 0.2% 0.1% | 1.1081 1.0% 0.9% | 1.1030 1.5% 0.5% | 1.0843 3.2% 1.7% |

Chair Yellen explained the removal of the word “patience” from the advanced guidance at the press conference following the FOMC meeting on Mar 18, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20150318.pdf):

“In other words, just because we removed the word “patient” from the statement doesn’t mean we are going to be impatient. Moreover, even after the initial increase in the target funds rate, our policy is likely to remain highly accommodative to support continued progress toward our objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation.”

Exchange rate volatility is increasing in response of “impatience” in financial markets with monetary policy guidance and measures:

| Fri Mar 6 | Mon 9 | Tue 10 | Wed 11 | Thu 12 | Fri 13 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0843 3.2% 1.7% | 1.0853 -0.1% -0.1% | 1.0700 1.3% 1.4% | 1.0548 2.7% 1.4% | 1.0637 1.9% -0.8% | 1.0497 3.2% 1.3% |

| Fri Mar 13 | Mon 16 | Tue 17 | Wed 18 | Thu 19 | Fri 20 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0497 3.2% 1.3% | 1.0570 -0.7% -0.7% | 1.0598 -1.0% -0.3% | 1.0864 -3.5% -2.5% | 1.0661 -1.6% 1.9% | 1.0821 -3.1% -1.5% |

| Fri Apr 24 | Mon 27 | Tue 28 | Wed 29 | Thu 30 | May Fri 1 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0874 -0.6% -0.4% | 1.0891 -0.2% -0.2% | 1.0983 -1.0% -0.8% | 1.1130 -2.4% -1.3% | 1.1223 -3.2% -0.8% | 1.1199 -3.0% 0.2% |

In a speech at Brown University on May 22, 2015, Chair Yellen stated (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150522a.htm):

“For this reason, if the economy continues to improve as I expect, I think it will be appropriate at some point this year to take the initial step to raise the federal funds rate target and begin the process of normalizing monetary policy. To support taking this step, however, I will need to see continued improvement in labor market conditions, and I will need to be reasonably confident that inflation will move back to 2 percent over the medium term. After we begin raising the federal funds rate, I anticipate that the pace of normalization is likely to be gradual. The various headwinds that are still restraining the economy, as I said, will likely take some time to fully abate, and the pace of that improvement is highly uncertain.”

The US dollar appreciated 3.8 percent relative to the euro in the week of May 22, 2015:

| Fri May 15 | Mon 18 | Tue 19 | Wed 20 | Thu 21 | Fri 22 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1449 -2.2% -0.3% | 1.1317 1.2% 1.2% | 1.1150 2.6% 1.5% | 1.1096 3.1% 0.5% | 1.1113 2.9% -0.2% | 1.1015 3.8% 0.9% |

The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, warned on Jun 4, 2015, that: (http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2015/06/04/u-s-economy-returning-to-growth-but-pockets-of-vulnerability/):

“The Fed’s first rate increase in almost 9 years is being carefully prepared and telegraphed. Nevertheless, regardless of the timing, higher US policy rates could still result in significant market volatility with financial stability consequences that go well beyond US borders. I weighing these risks, we think there is a case for waiting to raise rates until there are more tangible signs of wage or price inflation than are currently evident. Even after the first rate increase, a gradual rise in the federal fund rates will likely be appropriate.”

The President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, warned on Jun 3, 2015 that (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2015/html/is150603.en.html):

“But certainly one lesson is that we should get used to periods of higher volatility. At very low levels of interest rates, asset prices tend to show higher volatility…the Governing Council was unanimous in its assessment that we should look through these developments and maintain a steady monetary policy stance.”

The Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Janet L. Yellen, stated on Jul 10, 2015 that (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150710a.htm):

“Based on my outlook, I expect that it will be appropriate at some point later this year to take the first step to raise the federal funds rate and thus begin normalizing monetary policy. But I want to emphasize that the course of the economy and inflation remains highly uncertain, and unanticipated developments could delay or accelerate this first step. I currently anticipate that the appropriate pace of normalization will be gradual, and that monetary policy will need to be highly supportive of economic activity for quite some time. The projections of most of my FOMC colleagues indicate that they have similar expectations for the likely path of the federal funds rate. But, again, both the course of the economy and inflation are uncertain. If progress toward our employment and inflation goals is more rapid than expected, it may be appropriate to remove monetary policy accommodation more quickly. However, if progress toward our goals is slower than anticipated, then the Committee may move more slowly in normalizing policy.”

There is essentially the same view in the Testimony of Chair Yellen in delivering the Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the Congress on Jul 15, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20150715a.htm).

At the press conference after the meeting of the FOMC on Sep 17, 2015, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20150917.pdf 4):

“The outlook abroad appears to have become more uncertain of late, and heightened concerns about growth in China and other emerging market economies have led to notable volatility in financial markets. Developments since our July meeting, including the drop in equity prices, the further appreciation of the dollar, and a widening in risk spreads, have tightened overall financial conditions to some extent. These developments may restrain U.S. economic activity somewhat and are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation in the near term. Given the significant economic and financial interconnections between the United States and the rest of the world, the situation abroad bears close watching.”

Some equity markets fell on Fri Sep 18, 2015:

| Fri Sep 11 | Mon 14 | Tue 15 | Wed 16 | Thu 17 | Fri 18 |

| DJIA 16433.09 2.1% 0.6% | 16370.96 -0.4% -0.4% | 16599.85 1.0% 1.4% | 16739.95 1.9% 0.8% | 16674.74 1.5% -0.4% | 16384.58 -0.3% -1.7% |

| Nikkei 225 18264.22 2.7% -0.2% | 17965.70 -1.6% -1.6% | 18026.48 -1.3% 0.3% | 18171.60 -0.5% 0.8% | 18432.27 0.9% 1.4% | 18070.21 -1.1% -2.0% |

| DAX 10123.56 0.9% -0.9% | 10131.74 0.1% 0.1% | 10188.13 0.6% 0.6% | 10227.21 1.0% 0.4% | 10229.58 1.0% 0.0% | 9916.16 -2.0% -3.1% |

Frank H. Knight (1963, 233), in Risk, uncertainty and profit, distinguishes between measurable risk and unmeasurable uncertainty. Chair Yellen, in a lecture on “Inflation dynamics and monetary policy,” on Sep 24, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20150924a.htm), states that (emphasis added):

· “The economic outlook, of course, is highly uncertain”

· “Considerable uncertainties also surround the outlook for economic activity”

· “Given the highly uncertain nature of the outlook…”

Is there a “science” or even “art” of central banking under this extreme uncertainty in which policy does not generate higher volatility of money, income, prices and values of financial assets?

Lingling Wei, writing on Oct 23, 2015, on China’s central bank moves to spur economic growth,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-central-bank-cuts-rates-1445601495), analyzes the reduction by the People’s Bank of China (http://www.pbc.gov.cn/ http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130437/index.html) of borrowing and lending rates of banks by 50 basis points and reserve requirements of banks by 50 basis points. Paul Vigna, writing on Oct 23, 2015, on “Stocks rally out of correction territory on latest central bank boost,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2015/10/23/stocks-rally-out-of-correction-territory-on-latest-central-bank-boost/), analyzes the rally in financial markets following the statement on Oct 22, 2015, by the President of the European Central Bank (ECB) Mario Draghi of consideration of new quantitative measures in Dec 2015 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0814riKW25k&rel=0) and the reduction of bank lending/deposit rates and reserve requirements of banks by the People’s Bank of China on Oct 23, 2015. The dollar revalued 2.8 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23, 2015, following the intended easing of the European Central Bank. The DJIA rose 2.8 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23 and the DAX index of German equities rose 5.4 percent from Oct 21 to Oct 23, 2015.

| Fri Oct 16 | Mon 19 | Tue 20 | Wed 21 | Thu 22 | Fri 23 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1350 0.1% 0.3% | 1.1327 0.2% 0.2% | 1.1348 0.0% -0.2% | 1.1340 0.1% 0.1% | 1.1110 2.1% 2.0% | 1.1018 2.9% 0.8% |

| DJIA 17215.97 0.8% 0.4% | 17230.54 0.1% 0.1% | 17217.11 0.0% -0.1% | 17168.61 -0.3% -0.3% | 17489.16 1.6% 1.9% | 17646.70 2.5% 0.9% |

| Dow Global 2421.58 0.3% 0.6% | 2414.33 -0.3% -0.3% | 2411.03 -0.4% -0.1% | 2411.27 -0.4% 0.0% | 2434.79 0.5% 1.0% | 2458.13 1.5% 1.0% |

| DJ Asia Pacific 1402.31 1.1% 0.3% | 1398.80 -0.3% -0.3% | 1395.06 -0.5% -0.3% | 1402.68 0.0% 0.5% | 1396.03 -0.4% -0.5% | 1415.50 0.9% 1.4% |

| Nikkei 225 18291.80 -0.8% 1.1% | 18131.23 -0.9% -0.9% | 18207.15 -0.5% 0.4% | 18554.28 1.4% 1.9% | 18435.87 0.8% -0.6% | 18825.30 2.9% 2.1% |

| Shanghai 3391.35 6.5% 1.6% | 3386.70 -0.1% -0.1% | 3425.33 1.0% 1.1% | 3320.68 -2.1% -3.1% | 3368.74 -0.7% 1.4% | 3412.43 0.6% 1.3% |

| DAX 10104.43 0.1% 0.4% | 10164.31 0.6% 0.6% | 10147.68 0.4% -0.2% | 10238.10 1.3% 0.9% | 10491.97 3.8% 2.5% | 10794.54 6.8% 2.9% |

Ben Leubsdorf, writing on “Fed’s Yellen: December is “Live Possibility” for First Rate Increase,” on Nov 4, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-yellen-december-is-live-possibility-for-first-rate-increase-1446654282) quotes Chair Yellen that a rate increase in “December would be a live possibility.” The remark of Chair Yellen was during a hearing on supervision and regulation before the Committee on Financial Services, US House of Representatives (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20151104a.htm) and a day before the release of the employment situation report for Oct 2015 (Section I). The dollar revalued 2.4 percent during the week. The euro has devalued 45.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Jan 15, 2016.

| Fri Oct 30 | Mon 2 | Tue 3 | Wed 4 | Thu 5 | Fri 6 |

| USD/ EUR 1.1007 0.1% -0.3% | 1.1016 -0.1% -0.1% | 1.0965 0.4% 0.5% | 1.0867 1.3% 0.9% | 1.0884 1.1% -0.2% | 1.0742 2.4% 1.3% |

The release on Nov 18, 2015 of the minutes of the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) meeting held on Oct 28, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20151028.htm) states:

“Most participants anticipated that, based on their assessment of the current economic situation and their outlook for economic activity, the labor market, and inflation, these conditions [for interest rate increase] could well be met by the time of the next meeting. Nonetheless, they emphasized that the actual decision would depend on the implications for the medium-term economic outlook of the data received over the upcoming intermeeting period… It was noted that beginning the normalization process relatively soon would make it more likely that the policy trajectory after liftoff could be shallow.”

Markets could have interpreted a symbolic increase in the fed funds rate at the meeting of the FOMC on Dec 15-16, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm) followed by “shallow” increases, explaining the sharp increase in stock market values and appreciation of the dollar after the release of the minutes on Nov 18, 2015:

| Fri Nov 13 | Mon 16 | Tue 17 | Wed 18 | Thu 19 | Fri 20 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0774 -0.3% 0.4% | 1.0686 0.8% 0.8% | 1.0644 1.2% 0.4% | 1.0660 1.1% -0.2% | 1.0735 0.4% -0.7% | 1.0647 1.2% 0.8% |

| DJIA 17245.24 -3.7% -1.2% | 17483.01 1.4% 1.4% | 17489.50 1.4% 0.0% | 17737.16 2.9% 1.4% | 17732.75 2.8% 0.0% | 17823.81 3.4% 0.5% |

| DAX 10708.40 -2.5% -0.7% | 10713.23 0.0% 0.0% | 10971.04 2.5% 2.4% | 10959.95 2.3% -0.1% | 11085.44 3.5% 1.1% | 11119.83 3.8% 0.3% |

In testimony before The Joint Economic Committee of Congress on Dec 3, 2015 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20151203a.htm), Chair Yellen reiterated that the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) “anticipates that even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic condition may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below the Committee views as normal in the longer run.” Todd Buell and Katy Burne, writing on “Draghi says ECB could step up stimulus efforts if necessary,” on Dec 4, 2015, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/draghi-says-ecb-could-step-up-stimulus-efforts-if-necessary-1449252934), analyze that the President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, reassured financial markets that the ECB will increase stimulus if required to raise inflation the euro area to targets. The USD depreciated 3.1 percent on Thu Dec 3, 2015 after weaker than expected measures by the European Central Bank. DJIA fell 1.4 percent on Dec 3 and increased 2.1 percent on Dec 4. DAX fell 3.6 percent on Dec 3.

| Fri Nov 27 | Mon 30 | Tue 1 | Wed 2 | Thu 3 | Fri 4 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0594 0.5% 0.2% | 1.0565 0.3% 0.3% | 1.0634 -0.4% -0.7% | 1.0616 -0.2% 0.2% | 1.0941 -3.3% -3.1% | 1.0885 -2.7% 0.5% |

| DJIA 17798.49 -0.1% -0.1% | 17719.92 -0.4% -0.4% | 17888.35 0.5% 1.0% | 17729.68 -0.4% -0.9% | 17477.67 -1.8% -1.4% | 17847.63 0.3% 2.1% |

| DAX 11293.76 1.6% -0.2% | 11382.23 0.8% 0.8% | 11261.24 -0.3% -1.1% | 11190.02 -0.9% -0.6% | 10789.24 -4.5% -3.6% | 10752.10 -4.8% -0.3% |

At the press conference following the meeting of the FOMC on Dec 16, 2015, Chair Yellen states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20151216.pdf page 8):

“And we recognize that monetary policy operates with lags. We would like to be able to move in a prudent, and as we've emphasized, gradual manner. It's been a long time since the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates, and I think it's prudent to be able to watch what the impact is on financial conditions and spending in the economy and moving in a timely fashion enables us to do this.”

The implication of this statement is that the state of the art is not accurate in analyzing the effects of monetary policy on financial markets and economic activity. The US dollar appreciated and equities fluctuated:

| Fri Dec 11 | Mon 14 | Tue 15 | Wed 16 | Thu 17 | Fri 18 |

| USD/ EUR 1.0991 -1.0% -0.4% | 1.0993 0.0% 0.0% | 1.0932 0.5% 0.6% | 1.0913 0.7% 0.2% | 1.0827 1.5% 0.8% | 1.0868 1.1% -0.4% |

| DJIA 17265.21 -3.3% -1.8% | 17368.50 0.6% 0.6% | 17524.91 1.5% 0.9% | 17749.09 2.8% 1.3% | 17495.84 1.3% -1.4% | 17128.55 -0.8% -2.1% |

| DAX 10340.06 -3.8% -2.4% | 10139.34 -1.9% -1.9% | 10450.38 -1.1% 3.1% | 10469.26 1.2% 0.2% | 10738.12 3.8% 2.6% | 10608.19 2.6% -1.2% |

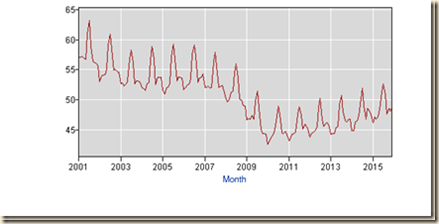

Chart VIII-1, Fed Funds Rate and Yields of Ten-year Treasury Constant Maturity and Baa Seasoned Corporate Bond, Jan 2, 2001 to Jan 14, 2015

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Table VIII-3, Selected Data Points in Chart VIII-1, % per Year

| Fed Funds Overnight Rate | 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity | Seasoned Baa Corporate Bond | |

| 1/2/2001 | 6.67 | 4.92 | 7.91 |

| 10/1/2002 | 1.85 | 3.72 | 7.46 |

| 7/3/2003 | 0.96 | 3.67 | 6.39 |

| 6/22/2004 | 1.00 | 4.72 | 6.77 |

| 6/28/2006 | 5.06 | 5.25 | 6.94 |

| 9/17/2008 | 2.80 | 3.41 | 7.25 |

| 10/26/2008 | 0.09 | 2.16 | 8.00 |

| 10/31/2008 | 0.22 | 4.01 | 9.54 |

| 4/6/2009 | 0.14 | 2.95 | 8.63 |

| 4/5/2010 | 0.20 | 4.01 | 6.44 |

| 2/4/2011 | 0.17 | 3.68 | 6.25 |

| 7/25/2012 | 0.15 | 1.43 | 4.73 |

| 5/1/13 | 0.14 | 1.66 | 4.48 |

| 9/5/13 | 0.089 | 2.98 | 5.53 |

| 11/21/2013 | 0.09 | 2.79 | 5.44 |

| 11/26/13 | 0.09 | 2.74 | 5.34 (11/26/13) |

| 12/5/13 | 0.09 | 2.88 | 5.47 |

| 12/11/13 | 0.09 | 2.89 | 5.42 |

| 12/18/13 | 0.09 | 2.94 | 5.36 |

| 12/26/13 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.37 |

| 1/1/2014 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.34 |

| 1/8/2014 | 0.07 | 2.97 | 5.28 |

| 1/15/2014 | 0.07 | 2.86 | 5.18 |

| 1/22/2014 | 0.07 | 2.79 | 5.11 |

| 1/30/2014 | 0.07 | 2.72 | 5.08 |

| 2/6/2014 | 0.07 | 2.73 | 5.13 |

| 2/13/2014 | 0.06 | 2.73 | 5.12 |

| 2/20/14 | 0.07 | 2.76 | 5.15 |

| 2/27/14 | 0.07 | 2.65 | 5.01 |

| 3/6/14 | 0.08 | 2.74 | 5.11 |

| 3/13/14 | 0.08 | 2.66 | 5.05 |

| 3/20/14 | 0.08 | 2.79 | 5.13 |

| 3/27/14 | 0.08 | 2.69 | 4.95 |

| 4/3/14 | 0.08 | 2.80 | 5.04 |

| 4/10/14 | 0.08 | 2.65 | 4.89 |

| 4/17/14 | 0.09 | 2.73 | 4.89 |

| 4/24/14 | 0.10 | 2.70 | 4.84 |

| 5/1/14 | 0.09 | 2.63 | 4.77 |

| 5/8/14 | 0.08 | 2.61 | 4.79 |

| 5/15/14 | 0.09 | 2.50 | 4.72 |

| 5/22/14 | 0.09 | 2.56 | 4.81 |

| 5/29/14 | 0.09 | 2.45 | 4.69 |

| 6/05/14 | 0.09 | 2.59 | 4.83 |

| 6/12/14 | 0.09 | 2.58 | 4.79 |

| 6/19/14 | 0.10 | 2.64 | 4.83 |

| 6/26/14 | 0.10 | 2.53 | 4.71 |

| 7/2/14 | 0.10 | 2.64 | 4.84 |

| 7/10/14 | 0.09 | 2.55 | 4.75 |

| 7/17/14 | 0.09 | 2.47 | 4.69 |

| 7/24/14 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 4.72 |

| 7/31/14 | 0.08 | 2.58 | 4.75 |

| 8/7/14 | 0.09 | 2.43 | 4.71 |

| 8/14/14 | 0.09 | 2.40 | 4.69 |

| 8/21/14 | 0.09 | 2.41 | 4.69 |

| 8/28/14 | 0.09 | 2.34 | 4.57 |

| 9/04/14 | 0.09 | 2.45 | 4.70 |

| 9/11/14 | 0.09 | 2.54 | 4.79 |

| 9/18/14 | 0.09 | 2.63 | 4.91 |

| 9/25/14 | 0.09 | 2.52 | 4.79 |

| 10/02/14 | 0.09 | 2.44 | 4.76 |

| 10/09/14 | 0.08 | 2.34 | 4.68 |

| 10/16/14 | 0.09 | 2.17 | 4.64 |

| 10/23/14 | 0.09 | 2.29 | 4.71 |

| 11/13/14 | 0.09 | 2.35 | 4.82 |

| 11/20/14 | 0.10 | 2.34 | 4.86 |

| 11/26/14 | 0.10 | 2.24 | 4.73 |

| 12/04/14 | 0.12 | 2.25 | 4.78 |

| 12/11/14 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 4.72 |

| 12/18/14 | 0.13 | 2.22 | 4.78 |

| 12/23/14 | 0.13 | 2.26 | 4.79 |

| 12/30/14 | 0.06 | 2.20 | 4.69 |

| 1/8/15 | 0.12 | 2.03 | 4.57 |

| 1/15/15 | 0.12 | 1.77 | 4.42 |

| 1/22/15 | 0.12 | 1.90 | 4.49 |

| 1/29/15 | 0.11 | 1.77 | 4.35 |

| 2/05/15 | 0.12 | 1.83 | 4.43 |

| 2/12/15 | 0.12 | 1.99 | 4.53 |

| 2/19/15 | 0.12 | 2.11 | 4.64 |

| 2/26/15 | 0.11 | 2.03 | 4.47 |

| 3/5/215 | 0.11 | 2.11 | 4.58 |

| 3/12/15 | 0.11 | 2.10 | 4.56 |

| 3/19/15 | 0.12 | 1.98 | 4.48 |

| 3/26/15 | 0.11 | 2.01 | 4.56 |

| 4/03/15 | 0.12 | 1.92 | 4.47 |

| 4/9/15 | 0.12 | 1.97 | 4.50 |

| 4/16/15 | 0.13 | 1.90 | 4.45 |

| 4/23/15 | 0.13 | 1.96 | 4.50 |

| 5/1/15 | 0.08 | 2.05 | 4.65 |

| 5/7/15 | 0.13 | 2.18 | 4.82 |

| 5/14/15 | 0.13 | 2.23 | 4.97 |

| 5/21/15 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 4.94 |

| 5/28/15 | 0.12 | 2.13 | 4.88 |

| 6/04/15 | 0.13 | 2.31 | 5.03 |

| 6/11/15 | 0.13 | 2.39 | 5.10 |

| 6/18/15 | 0.14 | 2.35 | 5.17 |

| 6/25/15 | 0.13 | 2.40 | 5.20 |

| 7/1/15 | 0.13 | 2.43 | 5.26 |

| 7/9/15 | 0.13 | 2.32 | 5.20 |

| 7/16/15 | 0.14 | 2.36 | 5.24 |

| 7/23/15 | 0.13 | 2.28 | 5.13 |

| 7/30/15 | 0.14 | 2.28 | 5.16 |

| 8/06/15 | 0.14 | 2.23 | 5.15 |

| 8/20/15 | 0.15 | 2.09 | 5.13 |

| 8/27/15 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 5.33 |

| 9/03/15 | 0.14 | 2.18 | 5.35 |

| 9/10/15 | 0.14 | 2.23 | 5.35 |

| 9/17/15 | 0.14 | 2.21 | 5.39 |

| 9/25/15 | 0.14 | 2.13 | 5.29 |

| 10/01/15 | 0.13 | 2.05 | 5.36 |

| 10/08/15 | 0.13 | 2.12 | 5.40 |

| 10/15/15 | 0.13 | 2.04 | 5.33 |

| 10/22/15 | 0.12 | 2.04 | 5.30 |

| 10/29/15 | 0.12 | 2.19 | 5.40 |

| 11/05/15 | 0.12 | 2.26 | 5.44 |

| 11/12/15 | 0.12 | 2.32 | 5.51 |

| 11/19/15 | 0.12 | 2.24 | 5.44 |

| 11/25/15 | 0.12 | 2.23 | 5.44 |

| 12/03/15 | 0.13 | 2.33 | 5.51 |

| 12/10/15 | 0.14 | 2.24 | 5.43 |

| 12/17/15 | 0.37 | 2.24 | 5.45 |

| 12/23/15 | 0.36 | 2.27 | 5.53 |

| 12/30/15 | 0.35 | 2.31 | 5.54 |

| 1/07/2016 | 0.36 | 2.16 | 5.44 |

| 1/14/16 | 0.36 | 2.10 | 5.46 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chart VIII-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate of US dollars (USD) per euro (EUR), USD/EUR. The rate appreciated from USD 1.1811/EUR on Jan 8, 2015 to USD 1.0885/EUR on Jan 8, 2016 or 7.8 percent. The euro has devalued 45.7 percent relative to the dollar from the high on Jul 15, 2008 to Jan 15, 2016. US corporations with foreign transactions and net worth experience losses in their balance sheets in converting revenues from depreciated currencies to the dollar. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA fell at $22.7 billion in IIIQ2015 with increase of domestic industries at $7.3 billion, mostly because of increase of nonfinancial business at $15.8 billion, and decrease of profits from operations in the rest of the world at $30.0 billion. Receipts from the rest of the world fell at $7.2 billion. Total corporate profits with IVA and CCA were $2060.3 billion in IIIQ2015 of which $1685.1 billion from domestic industries, or 81.8 percent of the total, and $375.1 billion, or 18.2 percent, from the rest of the world. Nonfinancial corporate profits of $1298.6 billion account for 63.0 percent of the total. There is increase in corporate profits from devaluing the dollar with unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and decrease of corporate profits in revaluing the dollar with attempts at “normalization” or increases in interest rates. Conflicts arise while other central banks differ in their adjustment process. Table VI-3C provides quarterly estimates NSA of the external imbalance of the United States. The current account deficit seasonally adjusted increases from 2.2 percent of GDP in IIIQ2014 to 2.3 percent in IVQ2014. The current account deficit increases to 2.7 percent of GDP in IQ2015 and decreases to 2.5 percent of GDP in IIQ2015. The deficit increases to 2.7 percent of GDP in IIIQ2015. The net international investment position decreases from minus $6.2 trillion in IIIQ2014 to minus $7.0 trillion in IVQ2014, increasing at minus $6.8 trillion in IQ2015. The net international investment position increases to minus 6.7 trillion in IIQ2015 and increases to minus $7.3 trillion in IIIQ2015. The BEA explains as follows (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/2015/pdf/intinv315.pdf):

“The U.S. net international investment position at the end of the third quarter of 2015 was -$7,269.8 billion (preliminary) as the value of U.S. liabilities exceeded the value of U.S. assets. At the end of the second quarter, the net investment position was -$6,743.1 billion (revised). The decrease in the net investment position reflected equity price decreases for U.S. assets and liabilities and the depreciation of foreign currencies against the U.S. dollar. The net investment position decreased 7.8 percent in the third quarter, compared with an increase of 0.9 percent in the second quarter and an average quarterly decrease of 6.7 percent from the first quarter of 2011 through the first quarter of 2015. The net investment position was equal to 3.5 percent of the value of all U.S. financial assets at the end of the third quarter, up from 3.2 percent at the end of the second quarter” (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html)

The BEA explains further (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/intinv/2015/pdf/intinv315.pdf): “Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRS), Financial Accounts of the United States, Third Quarter 2015, Z.1. Statistical Release (Washington, DC: FRS, December 10, 2015). According to the December release, the value of all U.S. financial assets was $205,068.1 billion at the end of the third quarter. The value of U.S. assets abroad was $23,311.9 billion, or 11.4 percent of all U.S. financial assets, down from 11.8 percent at the end of the second quarter” (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2016/01/weakening-equities-and-dollar.html).

Chart VIII-2, Exchange Rate of US Dollars (USD) per Euro (EUR), Jan 8, 2015 to Jan 8, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/H10/default.htm

Chart VIII-3 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the yield of the 10-year Treasury constant maturity note from 1.99 percent on Oct 14, 2015 to 2.10 percent on Jan 14, 2016. There is turbulence in financial markets originating in a combination of intentions of normalizing or increasing US policy fed funds rate, quantitative easing in Europe and Japan and increasing perception of financial/economic risks.

Chart VIII-3, Yield of Ten-year Constant Maturity Treasury, Oct 14, 2015 to Jan 14, 2016

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Percentage changes of risk financial assets from the last day of the year relative to the last day of the earlier year are in Table I-1 from 2007 to 2015. There is mixed performance in 2015 with declines of 2.2 for DJIA, 0.7 percent for S&P 500, 6.0 percent for NYSE Financial, 6.6 percent for Dow Global and 2.5 percent for Dow Asia Pacific. There were increases of 9.1 percent for the Nikkei Average, 9.4 percent for Shanghai Composite and 9.6 percent for DAX of Germany. The US dollar appreciated 10.2 percent relative to the euro. Calendar year 2014 was satisfactory for most equity indexes but not as excellent as 2013. Shanghai Composite outperformed all equity indexes in Table I-1 in 2014 with increase of 52.9 percent after falling 6.7 percent in 2013. The second highest increase is 11.4 percent for the Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500). DAX of Germany gained 2.7 percent. NYSE Financial increased 5.6 percent and Dow Global 0.6 percent. Dow Asia Pacific decreased 1.6 percent while the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) increased 7.5 percent. The USD appreciated 12.0 percent relative to the EUR. Equities also outperformed in calendar year 2012. DAX gained 29.1 percent and NYSE Financial 25.9 percent. Equities soared in 2013. The Nikkei Average increased 56.7 percent. DJIA gained 26.5 percent and S&P 500 29.3 percent. DAX of Germany increased 25.5 percent. The dollar depreciated 4.2 percent relative to the euro. DJ UBS Commodities index fell 9.6 percent. Equities enjoyed a good year in 2012. Nikkei Average gained 22.9 percent in 2012. S&P increased 13.4 percent and DJIA 7.3 percent. Shanghai Composite increased 3.2 percent. Dow Global increased 10.7 percent and Dow Asia Pacific 13.1 percent. DJ UBS Commodities fell 1.8 percent. The only gain for a major equity index in Table I-1 for 2011 is 5.5 percent for the DJIA. S&P 500 is better than other equity markets by remaining flat for 2011. With the exception of a drop of 8.4 percent of the European equity index STOXX 50, all declines of equity markets in 2011 are in excess of 10 percent. China’s Shanghai Composite lost 21.7 percent. The equity index of Germany DAX fell 14.7 percent. The DJ UBS Commodities Index dropped 13.4 percent. Robin Wigglesworth, writing on Dec 30, 2011, on “$6.3tn wiped off markets in 2011,” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/483069d8-32f3-11e1-8e0d-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1i2BE7OPa), provides an estimate of $6.3 trillion erased from equity markets globally in 2011. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates US nominal GDP in 2011 at $15,517.9 billion (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The loss in equity markets worldwide in 2011 of $6.3 trillion is equivalent to about 40.6 percent of US GDP or economic activity in 2011. Table I-1 also provides the exchange rate of number of US dollars (USD) required in buying a unit of euro (EUR), USD/EUR. The dollar appreciated 3.1 percent on the last day of trading in 2011 relative to the last day of trading in 2010, suggesting risk aversion. Depreciation of the dollar by 1.8 percent in 2012 and 4.2 percent in 2013 suggests more favorable environment of risk appetite for carry trades from zero interest rates into risk financial assets. The final row of Table I-1 provides the yield of the ten-year Treasury, decreasing to 2.172 percent in 2014 and 2.269 percent in 2015. The yield of the ten-year Treasury increased to 3.030 percent in 2013, which is the highest since 3.292 percent in 2010 and 3.844 percent in 2008. The yield at year-end 2007 was 4.077 percent.

Table I-1, Percentage Change of Year-end Values of Financial Assets Relative to Earlier Year-end Values 2007-2014 and Year-end Yield of 10-Year Treasury Note

| ∆% | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 |

| DJIA | -2.2 | 7.5 | 26.5 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 11.0 | 18.8 | -33.8 | 6.4 |

| S&P 500 | -0.7 | 11.4 | 29.3 | 13.4 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 23.5 | -38.5 | 3.5 |

| NYSE Fin | -6.0 | 5.6 | 24.2 | 25.9 | -18.1 | 5.0 | 22.7 | -53.6 | -13.1 |

| Dow Global | -6.6 | 0.6 | 24.5 | 10.7 | -13.6 | 5.2 | 30.0 | -45.4 | 30.5 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -2.5 | -1.6 | 10.2 | 13.1 | -17.6 | 16.0 | 36.4 | -44.2 | 14.0 |

| Nikkei Av | 9.1 | 7.1 | 56.7 | 22.9 | -17.3 | -3.0 | 19.0 | -42.1 | -11.1 |

| Shanghai | 9.4 | 52.9 | -6.7 | 3.2 | -21.7 | -14.3 | 80.0 | -65.4 | 96.7 |

| DAX | 9.6 | 2.7 | 25.5 | 29.1 | -14.7 | 16.1 | 23.8 | -40.4 | 22.3 |

| USD/ EUR* | 10.2 | 12.0 | -4.2 | -1.8 | 3.1 | 6.6 | -2.5 | 4.3 | -10.6 |

| DJ UBS** Com | NA | -9.6 | -1.1 | -13.4 | 16.7 | 18.7 | -36.6 | 11.2 | |

| Year-end Yield 10-Year Treasury % | 2.269 | 2.172 | 3.030 | 1.758 | 2.027 | 3.292 | 3.844 | 2.157 | 4.077 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

**DJ UBS available only for 2013 and earlier years

Sources: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata

The other yearly percentage changes in Table I-2 are also revealing wide fluctuations in valuations of risk financial assets. To be sure, economic conditions and perceptions of the future do influence valuations of risk financial assets. It is also valid to contend that unconventional monetary policy magnifies fluctuations in these valuations by inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures with high leverage in risk financial assets such as equities, emerging equities, currencies, high-yield structured products and commodities futures and options. In fact, one of the alleged channels of transmission of unconventional monetary policy is through higher consumption induced by increases in wealth resulting from higher valuations of stock markets. Bernanke (2010WP) and Yellen (2011AS) reveal the emphasis of monetary policy on the impact of the rise of stock market valuations in stimulating consumption by wealth effects on household confidence. Unconventional monetary policy could also result in magnification of values of risk financial assets beyond actual discounted future cash flows, creating financial instability. Separating all these effects in practice may be quite difficult because they are observed simultaneously. Conclusive evidence would require contrasting what actually happened with the counterfactual of what would have happened in the absence of unconventional monetary policy and other effects (on counterfactuals see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State Vol I (2008a), 125, 136, Harberger (1971, 1997), Fishlow 1965, Fogel 1964, Fogel and Engerman 1974, North and Weingast 1989, Pelaez 1979, 26-7). There is no certainty or evidence that unconventional policies attain their intended effects without risks of costly side effects. Yearly fluctuations of financial assets in Table I-1 are quite wide. In 2007, for example, the equity index Dow Global increased 30.5 percent while DAX gained 22.3 percent and the Shanghai Composite jumped 96.7 percent. The DJIA gained only 6.4 percent as recession began in IVQ2007. The flight to government obligations in 2008 (Cochrane and Zingales 2009, Cochrane 2011Jan) was equivalent to the astronomical declines of world equity markets and commodities. The flight from risk is also in evidence in the appreciation of the dollar by 4.3 percent in 2008 with unwinding carry trades and with renewed carry trades in the depreciation of the dollar by 2.5 percent in 2009. Recovery still continued in 2010 with shocks of the European debt crisis in the spring and in Nov 2010. The flight from risk exposures dominated declines of valuations of risk financial assets in 2011.

Table I-2 is designed to provide a comparison of valuations of risk financial assets at the end of 2015 relative to valuations at the end of every year from 2007 to 2014. Table I-2A provides percentage changes of valuations from 2006 to 20015. There is a break in the process of valuation of financial assets in 2015 relative to 2014. There were declines in major indexes: 2.2 percent for DJIA, 0.7 percent for S&P 500, 6.0 percent for NYSE Financial, 6.6 percent for Dow Global and 2.5 percent for Dow Asia Pacific. There are increases in major indexes: 9.1 percent for Nikkei, 9.4 percent for Shanghai Composite and 9.6 percent for DAX of Germany. The DJIA index is 5.1 percent higher at the end of 2015 relative to the valuation at the end of 2013, 31.4 percent above the valuation at the end of 2007 and 39.8 percent higher relative to the valuation at the end of 2006. DJIA is higher by 98.5 percent at the end of 2015 relative to the depressed valuation at the end of 2008. Several indexes are still lower at the end of 2015 relative to the values at the end of 2007 with exception of gains of 31.4 for DJIA, 39.2 percent for S&P 500, 24.3 percent for Nikkei Average and 33.2 percent for DAX. Some equity indexes are higher at the end of 2015 relative to the end of 2006: DJIA by 39.8 percent, S&P by 44.1 percent, Dow Global by 9.2 percent, Nikkei Average by 10.5 percent, Shanghai Composite by 32.3 percent and DAX by 62.8 percent. The USD is 25.6 stronger at the end of 2015 relative to 2007 and 17.7 percent stronger relative to 2006. Zero interest rates do not devalue the dollar during prolonged bouts of relative risk aversion and portfolio reallocations. Low valuations of risk financial assets are intimately related to risk aversion in international financial markets because of the European debt crisis, weakness and unemployment in advanced economies, fiscal imbalances and slowing growth worldwide. Valuations of stock indexes for the US and Germany are peaking at the turn of 2014 into 2015 relative to 2007 and 2006 with recent sharp declines into 2016.

Table I-2, Percentage Change of Year-end 2015 Values of Financial Assets Relative to Year-end Values 2006-2014

| ∆% 15/ 14 | ∆% 15/ 13 | ∆% 15/ 12 | ∆% 15/ 11 | ∆% 15/ 10 | ∆% 15/ 09 | ∆% 15/ 08 | ∆% 15/ 07 | |

| DJIA | -2.2 | 5.1 | 33.0 | 42.6 | 50.5 | 67.1 | 98.5 | 31.4 |

| S&P 500 | -0.7 | 10.6 | 43.3 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 83.3 | 126.3 | 39.2 |

| NYSE Fin | -6.0 | -0.8 | 23.3 | 55.2 | 27.2 | 33.6 | 63.9 | -24.0 |

| Dow Global | -6.6 | -6.0 | 17.1 | 30.0 | 11.9 | 17.7 | 53.1 | -16.4 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -2.5 | -4.1 | 5.7 | 19.6 | -1.5 | 14.3 | 55.9 | -13.0 |

| Nikkei Av | 9.1 | 16.8 | 83.1 | 125.1 | 86.1 | 80.5 | 114.8 | 24.3 |

| Shanghai | 9.4 | 67.3 | 56.0 | 60.9 | 26.0 | 8.0 | 94.4 | -32.7 |

| DAX | 9.6 | 12.5 | 41.1 | 82.1 | 55.4 | 80.3 | 123.3 | 33.2 |

| USD/EUR* | 10.2 | 21.0 | 17.7 | 16.2 | 18.8 | 24.1 | 22.2 | 25.6 |

| DJ UBS** Com | NA | -9.6 | -10.6 | -22.6 | -9.7 | 7.3 | -32.0 | -24.4 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

**DJ UBS available only for 2013 and earlier years; percentage change is to 2013.

Sources: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata

Table I-2, Percentage Change of Year-end 2015 Values of Financial Assets Relative to Year-end Values 2006-2014

| ∆% 2015/2006 | |

| DJIA | 39.8 |

| S&P 500 | 44.1 |

| NYSE Fin | -34.0 |

| Dow Global | 9.2 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -0.8 |

| Nikkei Av | 10.5 |

| Shanghai | 32.3 |

| DAX | 62.8 |

| USD/EUR* | 17.7 |

| DJ UBS** Com | NA |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

**DJ UBS available only for 2013 and earlier years; percentage change is to 2013.

Sources: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata

The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets had proved strongest for commodity exposures but US equities have regained leadership. The DJIA has increased 65.1 percent since the trough of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe on Jul 16, 2010 to Jan 15, 2016; S&P 500 has gained 83.9 percent and DAX 68.3 percent. Before the current round of risk aversion, almost all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 1/15/16” in Table VI-4 had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010 followed by negative performance but now some valuations of equity indexes show varying behavior. China’s Shanghai Composite is 21.7 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 94.3 percent above the trough. DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 10.8 percent above the trough. Dow Global is 25.1 percent above the trough. STOXX 50 of 50 blue-chip European equities (http://www.stoxx.com/indices/index_information.html?symbol=sx5E) is 22.0 percent above the trough. NYSE Financial Index is 32.8 percent above the trough. DAX index of German equities (http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/DAX:IND) is 68.3 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 94.3 percent above the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 50.5 percent above the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 17,147.11 on Jan 15, 2016 (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata), which is 67.2 percent higher than 10,254.43 on Mar 11, 2011, on the date of the Tōhoku or Great East Japan Earthquake/tsunami. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar appreciated 8.4 percent relative to the euro. The dollar devalued before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 1/15/16” in Table VI-4 shows

decrease of 9.0 percent in the week for China’s Shanghai Composite. The Nikkei decreased 3.1 percent. DJ Asia Pacific decreased 3.2 percent. NYSE Financial decreased 3.4 percent in the week. Dow Global decreased 2.7 percent in the week of Jan 15, 2016. The DJIA decreased 2.2 percent and S&P 500 decreased 2.2 percent. DAX of Germany increased 3.1 percent. STOXX 50 decreased 3.0 percent. The USD appreciated 0.1 percent. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks and banking soundness, US and world growth slowdown and China’s growth tradeoffs. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table VI-4 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 1/15/16” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Jan 15, 2016. Most risk financial assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 1/15/16” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 1/15/16.” There are now several equity indexes above the peak in Table VI-4: DJIA 42.7 percent, S&P 500 54.5 percent, DAX 50.7 percent, Dow Global 2.0 percent, NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) 5.8 percent, Nikkei Average 50.5 percent, STOXX 50 3.3 percent. Shanghai Composite is 8.3 percent below the peak and DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 3.0 percent below the peak. The Shanghai Composite increased 46.9 percent from March 12, 2014, to Jan 15, 2016. The US dollar strengthened 27.8 percent relative to the peak. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr 2010 is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul 2010 because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. Sharp and continuing strengthening of the dollar is affecting balance sheets of US corporations with foreign operations (http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Pronouncement_C/SummaryPage&cid=900000010318). The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is following “financial and international developments” as part of the process of framing interest rate policy (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20150128a.htm). Theo Francis e Kate Linebaugh, writing on Oct 25, 2015, on “US Companies Warn of Slowing Economy, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-companies-warn-of-slowing-economy-1445818298) analyze the first contraction of earnings and revenue of big US companies. Production, sales and employment are slowing in a large variety of companies with some contracting. Corporate profits also suffer from revaluation of the dollar that constrains translation of foreign profits into dollar balance sheets. Francis and Linebaugh quote Thomson Reuters that analysts expect decline of earnings per share of 2.8 percent in IIIQ2015 relative to IIIQ2014 based on reports by one third of companies in the S&P 500. Sales would decline 4.0% in a third quarter for the first joint decline of earnings per share and revenue in the same quarter since IIIQ2009. Dollar revaluation also constrains corporate results.

Inyoung Hwang, writing on “Fed optimism spurs record bets against stock volatility,” on Aug 21, 2014, published in Bloomberg.com (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-08-21/fed-optimism-spurs-record-bets-against-stock-voalitlity.html), informs that the S&P 500 is trading at 16.6 times estimated earnings, which is higher than the five-year average of 14.3 Tom Lauricella, writing on Mar 31, 2014, on “Stock investors see hints of a stronger quarter,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304157204579473513864900656?mod=WSJ_smq0314_LeadStory&mg=reno64-wsj), finds views of stronger earnings among many money managers with positive factors for equity markets in continuing low interest rates and US economic growth. There is important information in the Quarterly Markets review of the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/public/page/quarterly-markets-review-03312014.html) for IQ2014. Alexandra Scaggs, writing on “Tepid profits, roaring stocks,” on May 16, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323398204578487460105747412.html), analyzes stabilization of earnings growth: 70 percent of 458 reporting companies in the S&P 500 stock index reported earnings above forecasts but sales fell 0.2 percent relative to forecasts of increase of 0.5 percent. Paul Vigna, writing on “Earnings are a margin story but for how long,” on May 17, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/05/17/earnings-are-a-margin-story-but-for-how-long/), analyzes that corporate profits increase with stagnating sales while companies manage costs tightly. More than 90 percent of S&P components reported moderate increase of earnings of 3.7 percent in IQ2013 relative to IQ2012 with decline of sales of 0.2 percent. Earnings and sales have been in declining trend. In IVQ2009, growth of earnings reached 104 percent and sales jumped 13 percent. Net margins reached 8.92 percent in IQ2013, which is almost the same at 8.95 percent in IIIQ2006. Operating margins are 9.58 percent. There is concern by market participants that reversion of margins to the mean could exert pressure on earnings unless there is more accelerated growth of sales. Vigna (op. cit.) finds sales growth limited by weak economic growth. Kate Linebaugh, writing on “Falling revenue dings stocks,” on Oct 20, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444592704578066933466076070.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), identifies a key financial vulnerability: falling revenues across markets for United States reporting companies. Global economic slowdown is reducing corporate sales and squeezing corporate strategies. Linebaugh quotes data from Thomson Reuters that 100 companies of the S&P 500 index have reported declining revenue only 1 percent higher in Jun-Sep 2012 relative to Jun-Sep 2011 but about 60 percent of the companies are reporting lower sales than expected by analysts with expectation that revenue for the S&P 500 will be lower in Jun-Sep 2012 for the entities represented in the index. Results of US companies are likely repeated worldwide. Future company cash flows derive from investment projects. In IQ1980, real gross private domestic investment in the US was $951.6 billion of chained 2009 dollars, growing to $1,290.7 billion in IQ1989 or 35.6 percent. Real gross private domestic investment in the US increased 9.8 percent from $2605.2 billion in IVQ2007 to $2,859.7 billion in IIIQ2015. Real private fixed investment increased 6.7 percent from $2,586.3 billion of chained 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,760.7 billion in IIIQ2015. Private fixed investment fell relative to IVQ2007 in all quarters preceding IIQ2014. Growth of real private investment is mediocre for all but four quarters from IIQ2011 to IQ2012. The investment decision of United States corporations is fractured in the current economic cycle in preference of cash.

There are three aspects. First, there is decrease in corporate profits. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at 25.5 billion in IVQ2014. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $123.0 billion in IQ2015 and increased at $70.5 billion in IIQ2015. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $33.1 billion in IIIQ2015. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA fell at $19.5 billion in IVQ2014 and decreased at $128.5 billion in IQ2015. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA increased at $39.2 billion in IIQ2015. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA decreased at $26.2 billion in IIIQ2015. Net dividends increased at $18.6 billion in IVQ2014. Net dividends increased at $6.3 billion in IQ2015. Net dividends increased at $1.1 billion in IIQ2015 and increased at $26.1 billion in IIIQ2015. Undistributed profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $38.1 billion in IVQ2014. Undistributed corporate profits fell at $134.7 billion in IQ2015 and increased at $38.0 billion in IIQ2015. Undistributed profits with IVA and CCA decreased at $52.2 billion in IIIQ2015. Undistributed corporate profits swelled 227.4 percent from $107.7 billion in IQ2007 to $352.6 billion in IIIQ2015 and changed signs from minus $55.9 billion in current dollars in IVQ2007. Uncertainty originating in fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy causes wide swings in expectations and decisions by the private sector with adverse effects on investment, real economic activity and employment. Second, sharp and continuing strengthening of the dollar is affecting balance sheets of US corporations with foreign operations (http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Pronouncement_C/SummaryPage&cid=900000010318) and the overall US economy. The bottom part of Table IA1-9 provides the breakdown of corporate profits with IVA and CCA in domestic industries and the rest of the world. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA fell at $33.1 billion in IIIQ2015 with decrease of domestic industries at $10.0 billion, mostly because of decrease of nonfinancial business at $11.8 billion, and decrease of profits from operations in the rest of the world at $23.1 billion. Receipts from the rest of the world fell at $3.5 billion. Total corporate profits with IVA and CCA were $2049.9 billion in IIIQ2015 of which $1667.9 billion from domestic industries, or 81.4 percent of the total, and $382.0 billion, or 18.6 percent, from the rest of the world. Nonfinancial corporate profits of $1271.0 billion account for 62.0 percent of the total. Third, there is reduction in the use of corporate cash for investment. Vipal Monga, David Benoit and Theo Francis, writing on “Companies send more cash back to shareholders,” published on May 26, 2015 in the Wall Street Journal (http://www.wsj.com/articles/companies-send-more-cash-back-to-shareholders-1432693805?tesla=y), use data of a study by Capital IQ conducted for the Wall Street Journal. This study shows that companies in the S&P 500 reduced investment in plant and equipment to median 29 percent of operating cash flow in 2013 from 33 percent in 2003 while increasing dividends and buybacks to median 36 percent in 2013 from 18 percent in 2003.

The basic valuation equation that is also used in capital budgeting postulates that the value of stocks or of an investment project is given by:

Where Rτ is expected revenue in the time horizon from τ =1 to T; Cτ denotes costs; and ρ is an appropriate rate of discount. In words, the value today of a stock or investment project is the net revenue, or revenue less costs, in the investment period from τ =1 to T discounted to the present by an appropriate rate of discount. In the current weak economy, revenues have been increasing more slowly than anticipated in investment plans. An increase in interest rates would affect discount rates used in calculations of present value, resulting in frustration of investment decisions. If V represents value of the stock or investment project, as ρ → ∞, meaning that interest rates increase without bound, then V → 0, or

declines. Equally, decline in expected revenue from the stock or project, Rτ, causes decline in valuation.

An intriguing issue is the difference in performance of valuations of risk financial assets and economic growth and employment. Paul A. Samuelson (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1970/samuelson-bio.html) popularized the view of the elusive relation between stock markets and economic activity in an often-quoted phrase “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” In the presence of zero interest rates forever, valuations of risk financial assets are likely to differ from the performance of the overall economy. The interrelations of financial and economic variables prove difficult to analyze and measure.

Table VI-4, Stock Indexes, Commodities, Dollar and 10-Year Treasury

| Peak | Trough | ∆% to Trough | ∆% Peak to 1/15/ /16 | ∆% Week 1/15/16 | ∆% Trough to 1/15/ 16 | |

| DJIA | 4/26/ | 7/2/10 | -13.6 | 42.7 | -2.2 | 65.1 |

| S&P 500 | 4/23/ | 7/20/ | -16.0 | 54.5 | -2.2 | 83.9 |

| NYSE Finance | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -20.3 | 5.8 | -3.4 | 32.8 |

| Dow Global | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -18.4 | 2.0 | -2.7 | 25.1 |

| Asia Pacific | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -12.5 | -3.0 | -3.2 | 10.8 |

| Japan Nikkei Aver. | 4/05/ | 8/31/ | -22.5 | 50.5 | -3.1 | 94.3 |

| China Shang. | 4/15/ | 7/02 | -24.7 | -8.3 | -9.0 | 21.7 |

| STOXX 50 | 4/15/10 | 7/2/10 | -15.3 | 3.3 | -3.0 | 22.0 |

| DAX | 4/26/ | 5/25/ | -10.5 | 50.7 | -3.1 | 68.3 |

| Dollar | 11/25 2009 | 6/7 | 21.2 | 27.8 | 0.1 | 8.4 |

| DJ UBS Comm. | 1/6/ | 7/2/10 | -14.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| 10-Year T Note | 4/5/ | 4/6/10 | 3.986 | 2.784 | 2.036 |

T: trough; Dollar: positive sign appreciation relative to euro (less dollars paid per euro), negative sign depreciation relative to euro (more dollars paid per euro)

Source: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

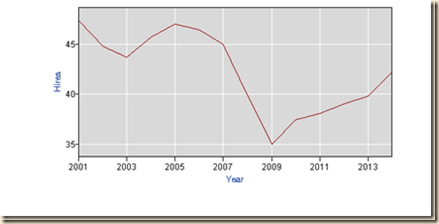

I Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels increased by only 4 percent from Jan 2009 to Jan 2012. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job in early 2012 is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer in the American Economic Review (Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 2012May) on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar amount of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn, there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2015/12/liftoff-of-interest-rates-with-volatile_17.html). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled. There are four subsections. IA1 Hiring Collapse provides the data and analysis on the weakness of hiring in the United States economy. IA2 Labor Underutilization provides the measures of labor underutilization of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Statistics on the decline of full-time employment are in IA3 Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. IA4 Theory and Reality of Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation: Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment provides the data on high unemployment of ages 16 to 24 years and of ages 45 years or over.