IMF View, Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates, United States Industrial Production, United States Producer Prices, World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

I IMF View

IIA United States Industrial Production

IIB United States Producer Prices

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

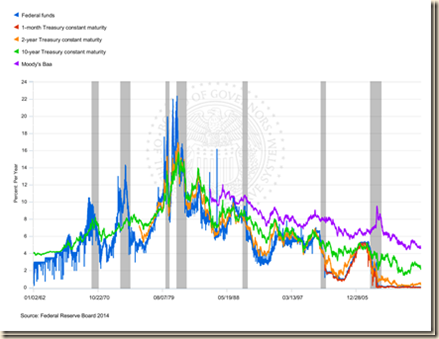

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

I IMF View of World Economy and Finance. The International Financial Institutions (IFI) consist of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank Group, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the multilateral development banks, which are the European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), The Global Recession Risk (2007), 8-19, 218-29, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 114-48, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 145-54). There are four types of contributions of the IFIs:

1. Safety Net. The IFIs contribute to crisis prevention and crisis resolution.

i. Crisis Prevention. An important form of contributing to crisis prevention is by surveillance of the world economy and finance by regions and individual countries. The IMF and World Bank conduct periodic regional and country evaluations and recommendations in consultations with member countries and also jointly with other international organizations. The IMF and the World Bank have been providing the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) by monitoring financial risks in member countries that can serve to mitigate them before they can become financial crises.

ii. Crisis Resolution. The IMF jointly with other IFIs provides assistance to countries in resolution of those crises that do occur. Currently, the IMF is cooperating with the government of Greece, European Union and European Central Bank in resolving the debt difficulties of Greece as it has done in the past in numerous other circumstances. Programs with other countries involved in the European debt crisis may also be developed.

2. Surveillance. The IMF conducts surveillance of the world economy, finance and public finance with continuous research and analysis. Important documents of this effort are the World Economic Outlook (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=29), Global Financial Stability Report (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/index.htm) and Fiscal Monitor (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=262).

3. Infrastructure and Development. The IFIs also engage in infrastructure and development, in particular the World Bank Group and the multilateral development banks.

4. Soft Law. Significant activity by IFIs has consisted of developing standards and codes under multiple forums. It is easier and faster to negotiate international agreements under soft law that are not binding but can be very effective (on soft law see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008c), 114-25). These norms and standards can solidify world economic and financial arrangements.

The objective of this section is to analyze current projections of the IMF database for the most important indicators.

Table I-1 is constructed with the database of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) to show GDP in dollars in 2012 and the growth rate of real GDP of the world and selected regional countries from 2013 to 2016. The data illustrate the concept often repeated of “two-speed recovery” of the world economy from the recession of 2007 to 2009. The IMF has changed its forecast of the world economy to 3.3 percent in 2013 but accelerating to 3.3 percent in 2014, 3.8 percent in 2015 and 4.0 percent in 2016. Slow-speed recovery occurs in the “major advanced economies” of the G7 that account for $34,523 billion of world output of $72,688 billion, or 47.5 percent, but are projected to grow at much lower rates than world output, 1.9 percent on average from 2013 to 2016 in contrast with 3.6 percent for the world as a whole. While the world would grow 15.2 percent in the four years from 2013 to 2016, the G7 as a whole would grow 8.5 percent. The difference in dollars of 2012 is rather high: growing by 15.2 percent would add around $11.0 trillion of output to the world economy, or roughly, two times the output of the economy of Japan of $5,938 billion but growing by 8.0 percent would add $5.8 trillion of output to the world, or about the output of Japan in 2012. The “two speed” concept is in reference to the growth of the 150 countries labeled as emerging and developing economies (EMDE) with joint output in 2012 of $27,512 billion, or 37.8 percent of world output. The EMDEs would grow cumulatively 20.7 percent or at the average yearly rate of 4.8 percent, contributing $5.7 trillion from 2013 to 2016 or the equivalent of somewhat less than the GDP of $8,387 billion of China in 2012. The final four countries in Table I-1 often referred as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), are large, rapidly growing emerging economies. Their combined output in 2012 adds to $14,511 billion, or 19.9 percent of world output, which is equivalent to 42.0 percent of the combined output of the major advanced economies of the G7.

Table I-1, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Real GDP Growth

| GDP USD 2012 | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | Real GDP ∆% | |

| World | 72,688 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.0 |

| G7 | 34,523 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Canada | 1,709 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| France | 2,688 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| DE | 3,428 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.9 | -0.2 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Japan | 5,938 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| UK | 2,471 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| US | 16,163 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 |

| Euro Area | 12,220 | -0.4 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| DE | 3,428 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| France | 2,688 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| Italy | 2,014 | -1.9 | -0.2 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| POT | 212 | -1.4 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Ireland | 211 | -0.3 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Greece | 249 | -3.9 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Spain | 1,323 | -1.2 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| EMDE | 27,512 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 5.0 | 5.2 |

| Brazil | 2,248 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| Russia | 2,017 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| India | 1,859 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 6.5 |

| China | 8,387 | 7.7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 6.8 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); POT: Portugal

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

Continuing high rates of unemployment in advanced economies constitute another characteristic of the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28). Table I-2 is constructed with the WEO database to provide rates of unemployment from 2012 to 2016 for major countries and regions. In fact, unemployment rates for 2013 in Table I-2 are high for all countries: unusually high for countries with high rates most of the time and unusually high for countries with low rates most of the time. The rates of unemployment are particularly high in 2013 for the countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe: 16.2 percent for Portugal (POT), 13.0 percent for Ireland, 27.3 percent for Greece, 26.1 percent for Spain and 12.2 percent for Italy, which is lower but still high. The G7 rate of unemployment is 7.1 percent. Unemployment rates are not likely to decrease substantially if slow growth persists in advanced economies.

Table I-2, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Unemployment Rate as Percent of Labor Force

| % Labor Force 2012 | % Labor Force 2013 | % Labor Force 2014 | % Labor Force 2015 | % Labor Force 2016 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 6.1 |

| Canada | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

| France | 9.8 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.9 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 11.3 |

| Japan | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.8 |

| UK | 8.0 | 7.6 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| US | 8.1 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 5.8 |

| Euro Area | 11.3 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.7 |

| DE | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| France | 9.8 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.9 |

| Italy | 10.7 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 11.3 |

| POT | 15.5 | 16.2 | 14.2 | 13.5 | 13.0 |

| Ireland | 14.7 | 13.0 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.1 |

| Greece | 24.2 | 27.3 | 25.8 | 23.8 | 20.9 |

| Spain | 24.8 | 26.1 | 24.6 | 23.5 | 22.4 |

| EMDE | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brazil | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| Russia | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 6.0 |

| India | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| China | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) is used to construct the debt/GDP ratios of regions and countries in Table I-3. The concept used is general government debt, which consists of central government debt, such as Treasury debt in the US, and all state and municipal debt. Net debt is provided for all countries except for the only available gross debt for China, Russia and India. The net debt/GDP ratio of the G7 increases from 85.5 in 2012 to 86.2 in 2016. G7 debt is pulled by the high debt of Japan that grows from 129.5 percent of GDP in 2012 to 140.3 percent of GDP in 2016. US general government debt increases from 79.4 percent of GDP in 2012 to 81.0 percent of GDP in 2016. Debt/GDP ratios of countries with sovereign debt difficulties in Europe are particularly worrisome. General government net debts of Italy, Greece and Portugal exceed 100 percent of GDP or are expected to exceed 100 percent of GDP by 2016. The only country with relatively lower debt/GDP ratio is Spain with 52.6 in 2012 but growing to 70.7 in 2016. Ireland’s debt/GDP ratio increases from 88.0 in 2012 to 91.2 in 2016. Fiscal adjustment, voluntary or forced by defaults, may squeeze further economic growth and employment in many countries as analyzed by Blanchard (2012WEOApr). Defaults could feed through exposures of banks and investors to financial institutions and economies in countries with sounder fiscal affairs.

Table I-3, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections, General Government Net Debt as Percent of GDP

| % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | % Debt/ | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | 85.5 | 85.5 | 86.2 | 86.5 | 86.2 |

| Canada | 36.7 | 37.6 | 38.6 | 39.1 | 39.0 |

| France | 81.7 | 84.7 | 88.1 | 90.6 | 91.9 |

| DE | 58.2 | 56.1 | 53.9 | 51.6 | 49.1 |

| Italy | 106.1 | 110.8 | 114.3 | 114.0 | 112.1 |

| Japan | 129.5 | 134.0 | 137.8 | 140.0 | 140.3 |

| UK | 80.9 | 82.5 | 83.9 | 85.0 | 84.8 |

| US | 79.4 | 80.4 | 80.8 | 80.9 | 81.0 |

| Euro Area | 70.1 | 72.3 | 73.9 | 74.0 | 73.2 |

| DE | 58.2 | 56.1 | 53.9 | 51.6 | 49.1 |

| France | 81.7 | 84.7 | 88.1 | 90.6 | 91.9 |

| Italy | 106.1 | 110.8 | 114.3 | 114.0 | 112.1 |

| POT | 114.0 | 118.5 | 123.8 | 123.6 | 121.5 |

| Ireland | 88.0 | 92.2 | 93.0 | 93.1 | 91.2 |

| Greece | 153.5 | 169.7 | 168.8 | 166.6 | 157.6 |

| Spain | 52.6 | 60.5 | 65.6 | 68.8 | 70.7 |

| EMDE* | 38.6 | 39.3 | 40.1 | 40.7 | 40.9 |

| Brazil | 35.3 | 33.6 | 33.7 | 32.9 | 32.5 |

| Russia* | 12.7 | 13.9 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 16.3 |

| India* | 66.6 | 61.5 | 60.5 | 59.5 | 58.5 |

| China* | 37.4 | 39.4 | 40.7 | 41.8 | 42.9 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries); *General Government Gross Debt as percent of GDP

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

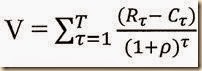

The primary balance consists of revenues less expenditures but excluding interest revenues and interest payments. It measures the capacity of a country to generate sufficient current revenue to meet current expenditures. There are various countries with primary surpluses in 2012: Germany 1.9 percent, Italy 2.3 percent, Brazil 2.1 percent and Russia 0.8 percent. There are also various countries with expected primary surpluses by 2016: Greece 4.5 percent, Italy 4.2 percent and so on. Most countries in Table I-4 face significant fiscal adjustment in the future without “fiscal space.” Investors in government securities may require higher yields when the share of individual government debts hit saturation shares in portfolios. The tool of analysis of Cochrane (2011Jan, 27, equation (16)) is the government debt valuation equation:

(Mt + Bt)/Pt = Et∫(1/Rt, t+τ)st+τdτ (1)

Equation (1) expresses the monetary, Mt, and debt, Bt, liabilities of the government, divided by the price level, Pt, in terms of the expected value discounted by the ex-post rate on government debt, Rt, t+τ, of the future primary surpluses st+τ, which are equal to Tt+τ – Gt+τ or difference between taxes, T, and government expenditures, G. Cochrane (2010A) provides the link to a web appendix demonstrating that it is possible to discount by the ex post Rt, t+τ. Expectations by investors of future primary balances of indebted governments may be less optimistic than those in Table I-4 because of government revenues constrained by low growth and government expenditures rigid because of entitlements. Political realities may also jeopardize structural reforms and fiscal austerity.

Table I-4, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of Primary General Government Net Lending/Borrowing as Percent of GDP

| % GDP 2012 | % GDP 2013 | % GDP 2014 | % GDP 2015 | % GDP 2016 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -4.7 | -3.1 | -2.8 | -1.8 | -1.3 |

| Canada | -2.8 | -2.7 | -2.1 | -1.6 | -1.1 |

| France | -2.4 | -2.1 | -2.3 | -2.2 | -1.7 |

| DE | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Italy | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 4.2 |

| Japan | -7.8 | -7.4 | -6.3 | -5.0 | -3.7 |

| UK | -5.6 | -4.5 | -3.5 | -1.9 | -0.3 |

| US | -6.3 | -3.6 | -3.4 | -2.2 | -2.0 |

| Euro Area | -1.0 | -0.5 | -0.4 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| DE | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| France | -2.4 | -2.1 | -2.3 | -2.2 | -1.7 |

| Italy | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 4.2 |

| POT | -2.5 | -0.6 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Ireland | -4.7 | -2.9 | -0.3 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| Greece | -1.3 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| Spain | -8.1 | -4.2 | -2.7 | -1.7 | -0.7 |

| EMDE | 0.8 | -0.1 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0.3 |

| Brazil | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| Russia | 0.8 | -0.9 | -0.4 | -0.5 | 0.03 |

| India | -3.1 | -2.6 | -2.6 | -2.3 | -2.2 |

| China | 0.7 | -0.4 | -0.5 | -0.3 | -0.3 |

*General Government Net Lending/Borrowing

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

The database of the World Economic Outlook of the IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) is used to obtain government net lending/borrowing as percent of GDP in Table I-5. Interest on government debt is added to the primary balance to obtain overall government fiscal balance in Table I-4. For highly indebted countries there is an even tougher challenge of fiscal consolidation. Adverse expectations on the success of fiscal consolidation may drive up yields on government securities that could create hurdles to adjustment, growth and employment.

Table I-5, IMF World Economic Outlook Database Projections of General Government Net Lending/Borrowing as Percent of GDP

| % GDP 2012 | % GDP 2013 | % GDP 2014 | % GDP 2015 | % GDP 2016 | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -6.8 | -5.1 | -4.7 | -3.8 | -3.3 |

| Canada | -3.4 | -3.0 | -2.6 | -2.1 | -1.7 |

| France | -4.9 | -4.2 | -4.4 | -4.3 | -3.7 |

| DE | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Italy | -2.9 | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.3 | -1.2 |

| Japan | -8.7 | -8.2 | -7.1 | -5.8 | -4.6 |

| UK | -8.0 | -5.8 | -5.3 | -4.1 | -2.9 |

| US | -8.6 | -5.8 | -5.5 | -4.3 | -4.2 |

| Euro Area | -3.7 | -3.0 | -2.9 | -2.5 | -1.9 |

| DE | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| France | -4.9 | -4.2 | -4.4 | -4.3 | -3.7 |

| Italy | -2.9 | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.3 | -1.2 |

| POT | -6.5 | -5.0 | -4.0 | -2.5 | -2.3 |

| Ireland | -7.8 | -6.7 | -4.2 | -2.8 | -1.7 |

| Greece | -6.4 | -3.2 | -2.7 | -1.9 | -0.6 |

| Spain | -10.6 | -7.1 | -5.7 | -4.7 | -3.8 |

| EMDE | -0.8 | -1.7 | -2.1 | -2.0 | -1.9 |

| Brazil | -2.8 | -3.3 | -3.9 | -3.1 | -3.0 |

| Russia | 0.4 | -1.3 | -0.9 | -1.1 | -0.6 |

| India | -7.4 | -7.2 | -7.2 | -6.7 | -6.5 |

| China | 0.2 | -0.9 | -1.0 | -0.8 | -0.8 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

There were some hopes that the sharp contraction of output during the global recession would eliminate current account imbalances. Table I-6 constructed with the database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) shows that external imbalances have been maintained in the form of current account deficits and surpluses. China’s current account surplus is 2.6 percent of GDP for 2012 and is projected to stabilize at 2.3 percent of GDP in 2016. At the same time, the current account deficit of the US is 2.9 percent of GDP in 2012 and is projected at 2.8 percent of GDP in 2016. The current account surplus of Germany is 7.4 percent for 2012 and remains at a high 5.5 percent of GDP in 2016. Japan’s current account surplus is 1.0 percent of GDP in 2012 and increases to 1.2 percent of GDP in 2016.

Table I-6, IMF World Economic Outlook Databank Projections, Current Account of Balance of Payments as Percent of GDP

| % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | % CA/ | |

| World | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| G7 | -1.1 | -0.9 | -0.9 | -1.0 | -1.0 |

| Canada | -3.4 | -3.2 | -2.7 | -2.5 | -2.4 |

| France | -2.1 | -1.3 | -1.4 | -1.0 | -0.7 |

| DE | 7.4 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| Italy | -0.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Japan | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| UK | -3.8 | -4.5 | -4.2 | -3.8 | -3.3 |

| US | -2.9 | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.6 | -2.8 |

| Euro Area | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| DE | 7.4 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| France | -2.1 | -1.3 | -1.4 | -1.0 | -0.7 |

| Italy | -0.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| POT | -2.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Ireland | 1.6 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Greece | -2.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Spain | -1.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| EMDE | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Brazil | -2.4 | -3.6 | -3.5 | -3.6 | -3.6 |

| Russia | 3.5 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.0 |

| India | -4.7 | -1.7 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.4 |

| China | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

Notes; DE: Germany; EMDE: Emerging and Developing Economies (150 countries)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

The G7 meeting in Washington on Apr 21 2006 of finance ministers and heads of central bank governors of the G7 established the “doctrine of shared responsibility” (G7 2006Apr):

“We, Ministers and Governors, reviewed a strategy for addressing global imbalances. We recognized that global imbalances are the product of a wide array of macroeconomic and microeconomic forces throughout the world economy that affect public and private sector saving and investment decisions. We reaffirmed our view that the adjustment of global imbalances:

- Is shared responsibility and requires participation by all regions in this global process;

- Will importantly entail the medium-term evolution of private saving and investment across countries as well as counterpart shifts in global capital flows; and

- Is best accomplished in a way that maximizes sustained growth, which requires strengthening policies and removing distortions to the adjustment process.

In this light, we reaffirmed our commitment to take vigorous action to address imbalances. We agreed that progress has been, and is being, made. The policies listed below not only would be helpful in addressing imbalances, but are more generally important to foster economic growth.

- In the United States, further action is needed to boost national saving by continuing fiscal consolidation, addressing entitlement spending, and raising private saving.

- In Europe, further action is needed to implement structural reforms for labor market, product, and services market flexibility, and to encourage domestic demand led growth.

- In Japan, further action is needed to ensure the recovery with fiscal soundness and long-term growth through structural reforms.

Others will play a critical role as part of the multilateral adjustment process.

- In emerging Asia, particularly China, greater flexibility in exchange rates is critical to allow necessary appreciations, as is strengthening domestic demand, lessening reliance on export-led growth strategies, and actions to strengthen financial sectors.

- In oil-producing countries, accelerated investment in capacity, increased economic diversification, enhanced exchange rate flexibility in some cases.

- Other current account surplus countries should encourage domestic consumption and investment, increase micro-economic flexibility and improve investment climates.

We recognized the important contribution that the IMF can make to multilateral surveillance.”

The concern at that time was that fiscal and current account global imbalances could result in disorderly correction with sharp devaluation of the dollar after an increase in premiums on yields of US Treasury debt (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007)). The IMF was entrusted with monitoring and coordinating action to resolve global imbalances. The G7 was eventually broadened to the formal G20 in the effort to coordinate policies of countries with external surpluses and deficits.

The database of the WEO (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) is used to contract Table I-7 with fiscal and current account imbalances projected for 2014 and 2016. The WEO finds the need to rebalance external and domestic demand (IMF 2011WEOSep xvii):

“Progress on this front has become even more important to sustain global growth. Some emerging market economies are contributing more domestic demand than is desirable (for example, several economies in Latin America); others are not contributing enough (for example, key economies in emerging Asia). The first set needs to restrain strong domestic demand by considerably reducing structural fiscal deficits and, in some cases, by further removing monetary accommodation. The second set of economies needs significant currency appreciation alongside structural reforms to reduce high surpluses of savings over investment. Such policies would help improve their resilience to shocks originating in the advanced economies as well as their medium-term growth potential.”

The IMF (2012WEOApr, XVII) explains decreasing importance of the issue of global imbalances as follows:

“The latest developments suggest that global current account imbalances are no longer expected to widen again, following their sharp reduction during the Great Recession. This is largely because the excessive consumption growth that characterized economies that ran large external deficits prior to the crisis has been wrung out and has not been offset by stronger consumption in .surplus economies. Accordingly, the global economy has experienced a loss of demand and growth in all regions relative to the boom years just before the crisis. Rebalancing activity in key surplus economies toward higher consumption, supported by more market-determined exchange rates, would help strengthen their prospects as well as those of the rest of the world.”

The IMF (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/02/pdf/c4.pdf) analyzes global imbalances as:

- Global current account imbalances have narrowed by more than a third from

their peak in 2006. Key imbalances—the large deficit of the United States and

the large surpluses of China and Japan—have more than halved.

- The narrowing in imbalances has largely been driven by demand contraction

(“expenditure reduction”) in deficit economies.

- Exchange rate adjustment has facilitated rebalancing in China and the United

States, but in general the contribution of exchange rate changes (“expenditure

switching”) to current account adjustment has been relatively modest.

- The narrowing of imbalances is expected to be durable, as domestic demand in

deficit economies is projected to remain well below pre-crisis trends.

- Since flow imbalances have narrowed but not reversed, net creditor and debtor

positions have widened further. Weak growth has also contributed to still high

ratios of net external liabilities to GDP in some debtor economies.

- Risks of a disruptive adjustment in global current account balances have

decreased, but global demand rebalancing remains a policy priority. Stronger

external demand will be instrumental for reviving growth in debtor countries and

reducing their net external liabilities.”

Table I-7, Fiscal Deficit, Current Account Deficit and Government Debt as % of GDP and 2011 Dollar GDP

| GDP 2014 | FD | CAD | Debt | FD%GDP | CAD%GDP | Debt | |

| US | 17416 | -3.4 | -2.5 | 80.8 | -2.0 | -2.8 | 81.0 |

| Japan | 4770 | -6.3 | 1.0 | 137.8 | -3.7 | 1.2 | 140.3 |

| UK | 2847 | -3.5 | -4.2 | 84.4 | -0.3 | -3.3 | 85.4 |

| Euro | 13241 | -0.4 | 2.0 | 73.9 | 0.7 | 1.9 | 73.2 |

| Ger | 3820 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 53.9 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 49.1 |

| France | 2902 | -2.3 | -1.4 | 88.1 | -1.7 | -0.7 | 91.9 |

| Italy | 2129 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 114.3 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 112.1 |

| Can | 1794 | -2.1 | -2.7 | 38.6 | -1.1 | -2.4 | 39.0 |

| China | 10355 | -0.5 | 1.8 | 40.7 | -0.3 | 2.3 | 42.9 |

| Brazil | 2244 | 1.3 | -3.5 | 33.6 | 2.5 | -3.6 | 32.5 |

Note: GER = Germany; Can = Canada; FD = fiscal deficit; CAD = current account deficit

FD is primary except total for China; Debt is net except gross for China

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

Brazil faced in the debt crisis of 1982 a more complex policy mix. Between 1977 and 1983, Brazil’s terms of trade, export prices relative to import prices, deteriorated 47 percent and 36 percent excluding oil (Pelaez 1987, 176-79; Pelaez 1986, 37-66; see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 178-87). Brazil had accumulated unsustainable foreign debt by borrowing to finance balance of payments deficits during the 1970s. Foreign lending virtually stopped. The German mark devalued strongly relative to the dollar such that Brazil’s products lost competitiveness in Germany and in multiple markets in competition with Germany. The resolution of the crisis was devaluation of the Brazilian currency by 30 percent relative to the dollar and subsequent maintenance of parity by monthly devaluation equal to inflation and indexing that resulted in financial stability by parity in external and internal interest rates avoiding capital flight. With a combination of declining imports, domestic import substitution and export growth, Brazil followed rapid growth in the US and grew out of the crisis with surprising GDP growth of 4.5 percent in 1984.

The euro zone faces a critical survival risk because several of its members may default on their sovereign obligations if not bailed out by the other members. The valuation equation of bonds is essential to understanding the stability of the euro area. An explanation is provided in this paragraph and readers interested in technical details are referred to the Subsection IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation. Contrary to the Wriston doctrine, investing in sovereign obligations is a credit decision. The value of a bond today is equal to the discounted value of future obligations of interest and principal until maturity. On Dec 30, 2011, the yield of the 2-year bond of the government of Greece was quoted around 100 percent. In contrast, the 2-year US Treasury note traded at 0.239 percent and the 10-year at 2.871 percent while the comparable 2-year government bond of Germany traded at 0.14 percent and the 10-year government bond of Germany traded at 1.83 percent. There is no need for sovereign ratings: the perceptions of investors are of relatively higher probability of default by Greece, defying Wriston (1982), and nil probability of default of the US Treasury and the German government. The essence of the sovereign credit decision is whether the sovereign will be able to finance new debt and refinance existing debt without interrupting service of interest and principal. Prices of sovereign bonds incorporate multiple anticipations such as inflation and liquidity premiums of long-term relative to short-term debt but also risk premiums on whether the sovereign’s debt can be managed as it increases without bound. The austerity measures of Italy are designed to increase the primary surplus, or government revenues less expenditures excluding interest, to ensure investors that Italy will have the fiscal strength to manage its debt exceeding 100 percent of GDP, which is the third largest in the world after the US and Japan. Appendix IIIE links the expectations on the primary surplus to the real current value of government monetary and fiscal obligations. As Blanchard (2011SepWEO) analyzes, fiscal consolidation to increase the primary surplus is facilitated by growth of the economy. Italy and the other indebted sovereigns in Europe face the dual challenge of increasing primary surpluses while maintaining growth of the economy (for the experience of Brazil in the debt crisis of 1982 see Pelaez 1986, 1987).

Much of the analysis and concern over the euro zone centers on the lack of credibility of the debt of a few countries while there is credibility of the debt of the euro zone as a whole. In practice, there is convergence in valuations and concerns toward the fact that there may not be credibility of the euro zone as a whole. The fluctuations of financial risk assets of members of the euro zone move together with risk aversion toward the countries with lack of debt credibility. This movement raises the need to consider analytically sovereign debt valuation of the euro zone as a whole in the essential analysis of whether the single-currency will survive without major changes.

Welfare economics considers the desirability of alternative states, which in this case would be evaluating the “value” of Germany (1) within and (2) outside the euro zone. Is the sum of the wealth of euro zone countries outside of the euro zone higher than the wealth of these countries maintaining the euro zone? On the choice of indicator of welfare, Hicks (1975, 324) argues:

“Partly as a result of the Keynesian revolution, but more (perhaps) because of statistical labours that were initially quite independent of it, the Social Product has now come right back into its old place. Modern economics—especially modern applied economics—is centered upon the Social Product, the Wealth of Nations, as it was in the days of Smith and Ricardo, but as it was not in the time that came between. So if modern theory is to be effective, if it is to deal with the questions which we in our time want to have answered, the size and growth of the Social Product are among the chief things with which it must concern itself. It is of course the objective Social Product on which attention must be fixed. We have indexes of production; we do not have—it is clear we cannot have—an Index of Welfare.”

If the burden of the debt of the euro zone falls on Germany and France or only on Germany, is the wealth of Germany and France or only Germany higher after breakup of the euro zone or if maintaining the euro zone? In practice, political realities will determine the decision through elections.

The prospects of survival of the euro zone are dire. Table I-8 is constructed with IMF World Economic Outlook database (http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28) for GDP in USD billions, primary net lending/borrowing as percent of GDP and general government debt as percent of GDP for selected regions and countries in 2015.

Table I-8, World and Selected Regional and Country GDP and Fiscal Situation

| GDP 2015 | Primary Net Lending Borrowing | General Government Net Debt | |

| World | 81,544 | ||

| Euro Zone | 13,466 | 0.0 | 74.0 |

| Portugal | 232 | 1.8 | 123.6 |

| Ireland | 253 | 1.2 | 93.1 |

| Greece | 252 | 3.0 | 166.6 |

| Spain | 1,422 | -1.7 | 68.8 |

| Major Advanced Economies G7 | 37,042 | -1.8 | 86.5 |

| United States | 18,287 | -2.2 | 80.9 |

| UK | 3,003 | -1.9 | 85.0 |

| Germany | 3,909 | 1.5 | 51.6 |

| France | 2,935 | -2.2 | 90.6 |

| Japan | 4,882 | -5.0 | 140.0 |

| Canada | 1,873 | -1.6 | 39.1 |

| Italy | 2,153 | 2.9 | 114.0 |

| China | 11,285 | -0.3 | 41.8** |

*Net Lending/borrowing**Gross Debt

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

The data in Table I-8 are used for some very simple calculations in Table I-9. The column “Net Debt USD Billions 2015” in Table I-9 is generated by applying the percentage in Table I-8 column “General Government Net Debt % GDP 2015” to the column “GDP 2015 USD Billions.” The total debt of France and Germany in 2015 is $4676.1 billion, as shown in row “B+C” in column “Net Debt USD Billions 2015” The sum of the debt of Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland is $4374.8 billion, adding rows D+E+F+G+H in column “Net Debt USD billions 2015.” There is some simple “unpleasant bond arithmetic” in the two final columns of Table I-9. Suppose the entire debt burdens of the five countries with probability of default were to be guaranteed by France and Germany, which de facto would be required by continuing the euro zone. The sum of the total debt of these five countries and the debt of France and Germany is shown in column “Debt as % of Germany plus France GDP” to reach $9050.9 billion, which would be equivalent to 132.2 percent of their combined GDP in 2015. Under this arrangement, the entire debt of selected members of the euro zone including debt of France and Germany would not have nil probability of default. The final column provides “Debt as % of Germany GDP” that would exceed 231.5 percent if including debt of France and 163.5 percent of German GDP if excluding French debt. The unpleasant bond arithmetic illustrates that there is a limit as to how far Germany and France can go in bailing out the countries with unsustainable sovereign debt without incurring severe pains of their own such as downgrades of their sovereign credit ratings. A central bank is not typically engaged in direct credit because of remembrance of inflation and abuse in the past. There is also a limit to operations of the European Central Bank in doubtful credit obligations. Wriston (1982) would prove to be wrong again that countries do not bankrupt but would have a consolation prize that similar to LBOs the sum of the individual values of euro zone members outside the current agreement exceeds the value of the whole euro zone. Internal rescues of French and German banks may be less costly than bailing out other euro zone countries so that they do not default on French and German banks. Analysis of fiscal stress is quite difficult without including another global recession in an economic cycle that is already mature by historical experience.

Table I-9, Guarantees of Debt of Sovereigns in Euro Area as Percent of GDP of Germany and France, USD Billions and %

| Net Debt USD Billions 2015 | Debt as % of Germany Plus France GDP | Debt as % of Germany GDP | |

| A Euro Area | 9,964.8 | ||

| B Germany | 2,017.0 | $9050.9 as % of $3909 =231.5% $6391.8 as % of $3909 =163.5% | |

| C France | 2,659.1 | ||

| B+C | 4,676.1 | GDP $6,844.0 Total Debt $9,050.9 Debt/GDP: 132.2% | |

| D Italy | 2,454.4 | ||

| E Spain | 978.3 | ||

| F Portugal | 286.8 | ||

| G Greece | 419.8 | ||

| H Ireland | 235.5 | ||

| Subtotal D+E+F+G+H | 4,374.8 |

Source: calculation with IMF data IMF World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

World trade projections of the IMF are in Table I-10. There is increasing growth of the volume of world trade of goods and services from 3.0 percent in 2013 to 5.0 percent in 2015 and 5.6 percent on average from 2016 to 2019. World trade would be slower for advanced economies while emerging and developing economies (EMDE) experience faster growth. World economic slowdown would be more challenging with lower growth of world trade.

Table I-10, IMF, Projections of World Trade, USD Billions, USD/Barrel and Annual ∆%

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average ∆% 2016-2019 | |

| World Trade Volume (Goods and Services) | 3.0 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 5.6 |

| Exports Goods & Services | 3.2 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 5.5 |

| Imports Goods & Services | 2.8 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 5.6 |

| World Trade Value of Exports Goods & Services USD Billion | 23,114 | 23,928 | 24,948 | Average ∆% 2006-2015 20,259 |

| Value of Exports of Goods USD Billion | 18,671 | 19,299 | 20,107 | Average ∆% 2006-2015 16,312 |

| Average Oil Price USD/Barrel | 104.07 | 102.76 | 99.36 | Average ∆% 2006-2015 88.85 |

| Average Annual ∆% Export Unit Value of Manufactures | -1.1 | -0.2 | -0.5 | Average ∆% 2006-2015 -0.6 |

| Exports of Goods & Services | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Average ∆% 2016-2019 |

| Euro Area | 1.8 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| EMDE | 4.4 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.1 |

| G7 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 4.9 |

| Imports Goods & Services | ||||

| Euro Area | 0.5 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| EMDE | 5.3 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 6.3 |

| G7 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods & Services | ||||

| Euro Area | 0.8 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.1 |

| EMDE | -0.2 | -0.02 | -0.6 | -0.4 |

| G7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | -0.2 | 0.0 |

| Terms of Trade of Goods | ||||

| Euro Area | 1.2 | 0.03 | -0.02 | -0.2 |

| EMDE | -0.2 | 0.2 | -0.4 | -0.3 |

| G7 | 0.9 | 0.3 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

Notes: Commodity Price Index includes Fuel and Non-fuel Prices; Commodity Industrial Inputs Price includes agricultural raw materials and metal prices; Oil price is average of WTI, Brent and Dubai

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook databank

http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28

II United States Industrial Production. There is socio-economic stress in the combination of adverse events and cyclical performance:

- Mediocre economic growth below potential and long-term trend, resulting in idle productive resources with GDP two trillion dollars below trend (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html). US GDP grew at the average rate of 3.3 percent per year from 1929 to 2013 with similar performance in whole cycles of contractions and expansions but only at 0.9 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2013. GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than what it would have been had it grown at trend of 3.0 percent.

- Private fixed investment stagnating at change of 0.3 percent in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html)

- Twenty seven million or 16.1 percent of the effective labor force unemployed or underemployed in involuntary part-time jobs with stagnating or declining real wages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html)

- Stagnating real disposable income per person or income per person after inflation and taxes (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html)

- Depressed hiring that does not afford an opportunity for reducing unemployment/underemployment and moving to better-paid jobs (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/global-financial-volatility-recovery.html)

- Productivity growth fell from 2.2 percent per year on average from 1947 to 2013 to 1.5 percent per year on average from 2007 to 2013 deteriorating future growth and prosperity (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html)

- Output of manufacturing in Aug at 17.4 percent below long-term trend since 1919 and at 11.8 percent below trend since 1986 (Section II and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html)

- Unsustainable government deficit/debt and balance of payments deficit (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/valuation-risks-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/02/theory-and-reality-of-cyclical-slow.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/interest-rate-risks-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Worldwide waves of inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/07/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html)

- Deteriorating terms of trade and net revenue margins of production across countries in squeeze of economic activity by carry trades induced by zero interest rates (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/monetary-policy-world-inflation-waves.html)

- Financial repression of interest rates and credit affecting the most people without means and access to sophisticated financial investments with likely adverse effects on income distribution and wealth disparity (Section II and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/geopolitical-and-financial-risks.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/08/fluctuating-financial-valuations.html)

- 45 million in poverty and 41 million without health insurance with family income adjusted for inflation regressing to 1995 levels (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/duration-dumping-and-peaking-valuations.html)

- Net worth of households and nonprofits organizations increasing by 7.5 percent after adjusting for inflation in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 when it would have been over 22.0 percent at trend of 3.1 percent per year in real terms from 1945 to 2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/06/financial-indecision-mediocre-cyclical.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/03/global-financial-risks-recovery-without.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html). Financial assets increased $14.2 trillion while nonfinancial assets increased $224.1 billion with likely concentration of wealth in those with access to sophisticated financial investments. Real estate assets adjusted for inflation fell 13.5 percent from 2007 to IIQ2014.

Industrial production increased 1.0 percent in Sep 2014 and decreased 0.2 percent in Aug 2014 after increasing 0.2 percent in Jul 2014, as shown in Table I-1, with all data seasonally adjusted. The Federal Reserve completed its annual revision of industrial production and capacity utilization on Mar 28, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm). The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production increased 1.0 percent in September and advanced at an annual rate of 3.2 percent in the third quarter of 2014, roughly its average quarterly increase since the end of 2010. In September, manufacturing output moved up 0.5 percent, while the indexes for mining and for utilities climbed 1.8 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively. For the third quarter as a whole, manufacturing production rose at an annual rate of 3.5 percent and mining output increased at an annual rate of 8.7 percent. The output of utilities fell at an annual rate of 8.5 percent for a second consecutive quarterly decline. At 105.1 percent of its 2007 average, total industrial production in September was 4.3 percent above its level of a year earlier. The capacity utilization rate for total industry moved up 0.6 percentage point in September to 79.3 percent, a rate that is 1.0 percentage point above its level of 12 months earlier but 0.8 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2013) average.”

In the six months ending in Sep 2014, United States national industrial production accumulated increase of 1.9 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 3.9 percent, which is lower than growth of 4.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014. Excluding growth of 1.0 percent in Sep 2014, growth in the remaining five months from Apr to Aug 2014 accumulated to 0.9 percent or 2.2 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production declined in one of the past six months. Industrial production expanded at annual equivalent 4.1 percent in the most recent quarter from Jul to Sep 2014 and at 3.7 percent in the prior quarter Apr-Jun 2014. Business equipment accumulated growth of 2.2 percent in the six months from Apr to Sep 2014 at the annual equivalent rate of 4.5 percent, which is close growth of 4.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “The capacity utilization rate for total industry moved up 0.6 percentage point in September to 79.3 percent, a rate that is 1.0 percentage point above its level of 12 months earlier but 0.8 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2013) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate with possible acceleration in past months.

Table I-1, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization, SA, ∆%

| 2014 | Sep 14 | Aug 14 | Jul 14 | Jun 14 | May 14 | Apr 14 | Sep 14/ Sep 13 |

| Total | 1.0 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 4.3 |

| Market | |||||||

| Final Products | 0.5 | -0.5 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 2.9 |

| Consumer Goods | 0.5 | -0.7 | 0.4 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.6 | 2.2 |

| Business Equipment | 0.3 | -0.2 | 1.2 | -0.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 4.6 |

| Non | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | -0.4 | 3.4 |

| Construction | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | -0.8 | 4.9 |

| Materials | 1.4 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 5.7 |

| Industry Groups | |||||||

| Manufacturing | 0.5 | -0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 3.7 |

| Mining | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 9.1 |

| Utilities | 3.9 | 1.2 | -3.0 | -2.0 | 0.2 | -5.1 | 0.9 |

| Capacity | 79.3 | 78.7 | 79.1 | 79.1 | 79.1 | 79.0 | 2.9 |

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Manufacturing increased 0.5 percent in Sep 2014 after decreasing 0.5 percent in Aug 2014 and increasing 0.7 percent in Jul 2014 seasonally adjusted, increasing 3.6 percent not seasonally adjusted in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014, as shown in Table I-2. Manufacturing grew cumulatively 1.7 percent in the six months ending in Sep 2014 or at the annual equivalent rate of 3.4 percent. Excluding the increase of 0.7 percent in Jul 2014, manufacturing accumulated growth of 1.0 percent from Apr 2013 to Sep 2014 or at the annual equivalent rate of 2.4 percent. Table I-2 provides a longer perspective of manufacturing in the US. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 into more recent months as shown by 12 months rates of growth. Growth rates appeared to be increasing again closer to 5 percent in Apr-Jun 2012 but deteriorated. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appeared to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession but the pace of manufacturing fell steadily in the past six months with some strength at the margin. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System conducted the annual revision of industrial production released on Mar 28, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm):

“The Federal Reserve has revised its index of industrial production (IP) and the related measures of capacity and capacity utilization. The annual revision for 2014 was more limited than in recent years because the source data required to extend the annual benchmark indexes of production into 2012 were mostly unavailable. Consequently, the IP indexes published with this revision are very little changed from previous estimates. Measured from fourth quarter to fourth quarter, total IP is now reported to have increased about 3 1/3 percent in each year from 2011 to 2013. Relative to the rates of change for total IP published earlier, the new rates are 1/2 percentage point higher in 2012 and little changed in any other year. Total IP still shows a peak-to-trough decline of about 17 percent for the most recent recession, and it still returned to its pre-recession peak in the fourth quarter of 2013.”

The bottom part of Table I-2 shows decline of manufacturing by 21.9 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increase by 19.9 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2013. Manufacturing grew 26.8 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Sep 2014. Manufacturing output in Sep 2014 is 1.0 percent below the peak in Jun 2007. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 would have accumulated to 22.1 percent. GDP in IIQ2014 would be $18,305.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,294.6 billion than actual $16,010.4 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.5 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.1 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html). US GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,010.4 billion in IIQ2014 or 6.8 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Sep 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.5550 in Sep 2014. The actual index NSA in Sep 2014 is 102.0228, which is 17.4 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 115.7028 in Sep 2014. The output of manufacturing at 102.0228 in Sep 2014 is 11.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table I-2, US, Monthly and 12-Month Rates of Growth of Manufacturing ∆%

| Month SA ∆% | 12-Month NSA ∆% | |

| Sep 2014 | 0.5 | 3.6 |

| Aug | -0.5 | 3.4 |

| Jul | 0.7 | 4.0 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 3.5 |

| May | 0.4 | 3.5 |

| Apr | 0.3 | 3.0 |

| Mar | 0.8 | 3.4 |

| Feb | 1.3 | 2.4 |

| Jan | -1.0 | 1.4 |

| Dec 2013 | 0.2 | 2.2 |

| Nov | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| Oct | 0.4 | 3.7 |

| Sep | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| Aug | 0.7 | 2.9 |

| Jul | -0.4 | 1.7 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| May | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Apr | -0.2 | 2.7 |

| Mar | 0.1 | 2.6 |

| Feb | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| Jan | -0.2 | 2.9 |

| Dec 2012 | 0.7 | 3.8 |

| Nov | 1.3 | 3.8 |

| Oct | -0.4 | 2.6 |

| Sep | 0.2 | 3.5 |

| Aug | -0.5 | 3.8 |

| Jul | 0.4 | 4.3 |

| Jun | 0.4 | 5.0 |

| May | -0.2 | 4.9 |

| Apr | 0.8 | 5.1 |

| Mar | -0.3 | 3.8 |

| Feb | 0.6 | 5.1 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Dec 2011 | 0.7 | 3.5 |

| Nov | -0.1 | 2.9 |

| Oct | 0.5 | 3.0 |

| Sep | 0.4 | 2.9 |

| Aug | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| Jul | 0.8 | 2.6 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| May | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| Apr | -0.6 | 3.2 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 4.9 |

| Feb | 0.0 | 5.4 |

| Jan | 0.2 | 5.7 |

| Dec 2010 | 0.4 | 6.3 |

| Nov | 0.2 | 5.4 |

| Oct | 0.1 | 6.6 |

| Sep | 0.1 | 6.9 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 7.4 |

| Jul | 0.8 | 7.8 |

| Jun | 0.0 | 9.3 |

| May | 1.5 | 8.8 |

| Apr | 0.9 | 7.0 |

| Mar | 1.3 | 4.8 |

| Feb | -0.1 | 1.3 |

| Jan | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Dec 2009 | -0.1 | -3.1 |

| Nov | 1.0 | -6.0 |

| Oct | 0.2 | -9.1 |

| Sep | 0.8 | -10.6 |

| Aug | 1.0 | -13.6 |

| Jul | 1.4 | -15.2 |

| Jun | -0.3 | -17.7 |

| May | -1.1 | -17.6 |

| Apr | -0.7 | -18.2 |

| Mar | -1.8 | -17.3 |

| Feb | -0.3 | -16.1 |

| Jan | -2.9 | -16.4 |

| Dec 2008 | -3.4 | -13.9 |

| Nov | -2.4 | -11.3 |

| Oct | -0.6 | -8.9 |

| Sep | -3.4 | -8.5 |

| Aug | -1.2 | -5.0 |

| Jul | -1.1 | -3.5 |

| Jun | -0.6 | -3.1 |

| May | -0.5 | -2.4 |

| Apr | -1.1 | -1.1 |

| Mar | -0.3 | -0.6 |

| Feb | -0.6 | 0.9 |

| Jan | -0.4 | 2.2 |

| Dec 2007 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| Nov | 0.5 | 3.3 |

| Oct | -0.4 | 2.8 |

| Sep | 0.5 | 2.9 |

| Aug | -0.4 | 2.6 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 3.5 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 3.0 |

| May | -0.1 | 3.1 |

| Apr | 0.7 | 3.6 |

| Mar | 0.8 | 2.5 |

| Feb | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| Jan | -0.5 | 1.3 |

| Dec 2006 | 2.7 | |

| Dec 2005 | 3.5 | |

| Dec 2004 | 3.8 | |

| Dec 2003 | 2.0 | |

| Dec 2002 | 2.4 | |

| Dec 2001 | -5.7 | |

| Dec 2000 | 0.7 | |

| Dec 1999 | 5.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2013 | 2.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 2012 | 2.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1986-Dec 1999 | 4.2 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1999-Dec 2006 | 1.3 | |

| Average ∆% Dec 1999-Dec 2013 | 0.6 | |

| ∆% Peak 103.0351 in 06/2007 to 96.4739 in 12/2013 | -6.4 | |

| ∆% Peak 103.0351 in 06/2007 to Trough 80.4551 in 4/2009 | -21.9 | |

| ∆% Trough 80.4551 in 04/2009 to 96.4739 in 12/2013 | 19.9 | |

| ∆% Trough 80.4551 in 04/2009 to 102.0228 in 9/2014 | 26.8 | |

| ∆% Peak 103.0351 on 06/2007 to 102.0228 in 9/2014 | -1.0 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

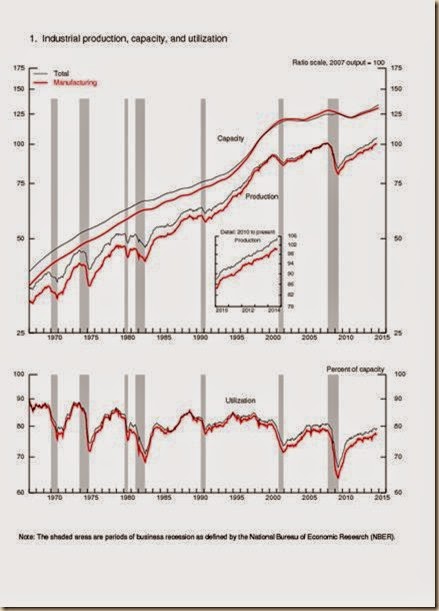

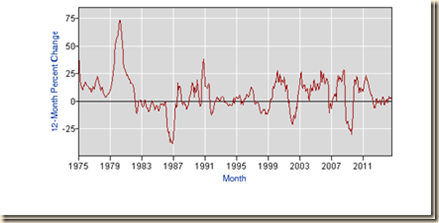

Chart I-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides industrial production, manufacturing and capacity since the 1970s. There was acceleration of growth of industrial production, manufacturing and capacity in the 1990s because of rapid growth of productivity in the US (Cobet and Wilson (2002); see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 135-44). The slopes of the curves flatten in the 2000s. Production and capacity have not recovered sufficiently above levels before the global recession, remaining like GDP below historical trend.

Chart I-1, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg1.gif

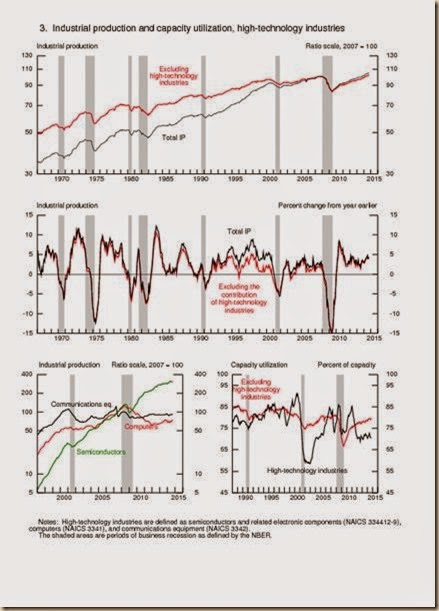

The modern industrial revolution of Jensen (1993) is captured in Chart I-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (for the literature on M&A and corporate control see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009a), 143-56, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), 49-59, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 46-49). The slope of the curve of total industrial production accelerates in the 1990s to a much higher rate of growth than the curve excluding high-technology industries. Growth rates decelerate into the 2000s and output and capacity utilization have not recovered fully from the strong impact of the global recession. Growth in the current cyclical expansion has been more subdued than in the prior comparably deep contractions in the 1970s and 1980s. Chart II-2 shows that the past recessions after World War II are the relevant ones for comparison with the recession after 2007 instead of common comparisons with the Great Depression (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html). The bottom left-hand part of Chart II-2 shows the strong growth of output of communication equipment, computers and semiconductor that continued from the 1990s into the 2000s. Output of semiconductors has already surpassed the level before the global recession.

Chart I-2, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization of High Technology Industries

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg3.gif

Additional detail on industrial production and capacity utilization is provided in Chart I-3 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Production of consumer durable goods fell sharply during the global recession by more than 30 percent and is still around the level before the contraction. Output of nondurable consumer goods fell around 10 percent and is some 5 percent below the level before the contraction. Output of business equipment fell sharply during the contraction of 2001 but began rapid growth again after 2004. An important characteristic is rapid growth of output of business equipment in the cyclical expansion after sharp contraction in the global recession. Output of defense and space only suffered reduction in the rate of growth during the global recession and surged ahead of the level before the contraction. Output of construction supplies collapsed during the global recession and is well below the level before the contraction. Output of energy materials was stagnant before the contraction but has recovered sharply above the level before the contraction.

Chart I-3, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/ipg2.gif

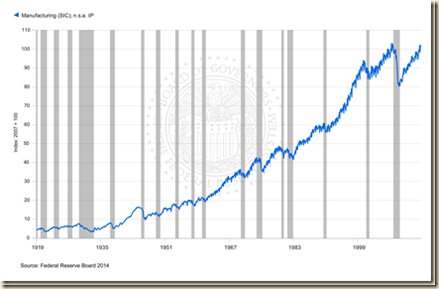

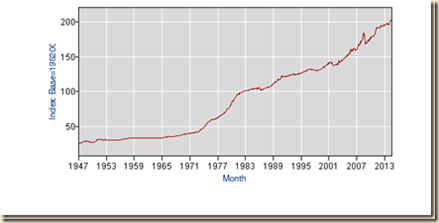

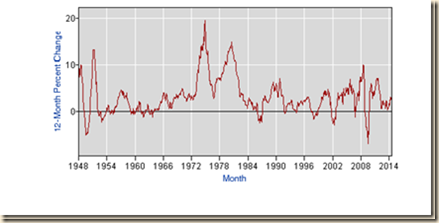

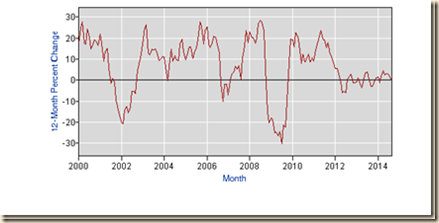

United States manufacturing output from 1919 to 2014 on a monthly basis is in Chart I-4 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The second industrial revolution of Jensen (1993) is quite evident in the acceleration of the rate of growth of output given by the sharper slope in the 1980s and 1990s. Growth was robust after the shallow recession of 2001 but dropped sharply during the global recession after IVQ2007. Manufacturing output recovered sharply but has not reached earlier levels and is losing momentum at the margin. Current output is well below the extrapolation of a long-term trend. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Sep 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.5550 in Sep 2014. The actual index NSA in Sep 2014 is 102.0228, which is 17.4 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 115.7028 in Sep 2014. The output of manufacturing at 102.0228 in Sep 2014 is 11.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Chart I-4, US, Manufacturing Output, 1919-2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Manufacturing jobs not seasonally adjusted increased 157,000 from Sep 2013 to

Sep 2014 or at the average monthly rate of 13,083. There are effects of the weaker economy and international trade together with the yearly adjustment of labor statistics. Industrial production increased 1.0 percent in Sep 2014 and decreased 0.2 percent in Aug 2014 after increasing 0.2 percent in Jul 2014, as shown in Table I-1, with all data seasonally adjusted. The Federal Reserve completed its annual revision of industrial production and capacity utilization on Mar 28, 2014 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/revisions/Current/DefaultRev.htm). The report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System states (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm):

“Industrial production increased 1.0 percent in September and advanced at an annual rate of 3.2 percent in the third quarter of 2014, roughly its average quarterly increase since the end of 2010. In September, manufacturing output moved up 0.5 percent, while the indexes for mining and for utilities climbed 1.8 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively. For the third quarter as a whole, manufacturing production rose at an annual rate of 3.5 percent and mining output increased at an annual rate of 8.7 percent. The output of utilities fell at an annual rate of 8.5 percent for a second consecutive quarterly decline. At 105.1 percent of its 2007 average, total industrial production in September was 4.3 percent above its level of a year earlier. The capacity utilization rate for total industry moved up 0.6 percentage point in September to 79.3 percent, a rate that is 1.0 percentage point above its level of 12 months earlier but 0.8 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2013) average.”

In the six months ending in Sep 2014, United States national industrial production accumulated increase of 1.9 percent at the annual equivalent rate of 3.9 percent, which is lower than growth of 4.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014. Excluding growth of 1.0 percent in Sep 2014, growth in the remaining five months from Apr to Aug 2014 accumulated to 0.9 percent or 2.2 percent annual equivalent. Industrial production declined in one of the past six months. Industrial production expanded at annual equivalent 4.1 percent in the most recent quarter from Jul to Sep 2014 and at 3.7 percent in the prior quarter Apr-Jun 2014. Business equipment accumulated growth of 2.2 percent in the six months from Apr to Sep 2014 at the annual equivalent rate of 4.5 percent, which is close growth of 4.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014. The Fed analyzes capacity utilization of total industry in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm): “The capacity utilization rate for total industry moved up 0.6 percentage point in September to 79.3 percent, a rate that is 1.0 percentage point above its level of 12 months earlier but 0.8 percentage point below its long-run (1972–2013) average.” United States industry apparently decelerated to a lower growth rate with possible acceleration in past months.

Manufacturing by 21.9 from the peak in Jun 2007 to the trough in Apr 2009 and increased by 19.9 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Dec 2013. Manufacturing grew 26.8 percent from the trough in Apr 2009 to Sep 2014. Manufacturing output in Sep 2014 is 1.0 percent below the peak in Jun 2007. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIQ2014 would have accumulated to 22.1 percent. GDP in IIQ2014 would be $18,305.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,294.6 billion than actual $16,010.4 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.5 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.1 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html). US GDP in IIQ2014 is 12.5 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,010.4 billion in IIQ2014 or 6.8 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.0 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Sep 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.5550 in Sep 2014. The actual index NSA in Sep 2014 is 102.0228, which is 17.4 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 115.7028 in Sep 2014. The output of manufacturing at 102.0228 in Sep 2014 is 11.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table I-13 provides national income by industry without capital consumption adjustment (WCCA). “Private industries” or economic activities have share of 87.3 percent in IIQ2014. Most of US national income is in the form of services. In Sep 2014, there were 139.752 million nonfarm jobs NSA in the US, according to estimates of the establishment survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm Table B-1). Total private jobs of 117.940 million NSA in Sep 2014 accounted for 84.4 percent of total nonfarm jobs of 139.752 million, of which 12.222 million, or 10.4 percent of total private jobs and 8.7 percent of total nonfarm jobs, were in manufacturing. Private service-producing jobs were 98.463 million NSA in Sep 2014, or 70.5 percent of total nonfarm jobs and 83.5 percent of total private-sector jobs. Manufacturing has share of 11.3 percent in US national income in IIQ2014 and durable goods 6.4 percent, as shown in Table I-13. Most income in the US originates in services. Subsidies and similar measures designed to increase manufacturing jobs will not increase economic growth and employment and may actually reduce growth by diverting resources away from currently employment-creating activities because of the drain of taxation.

Table I-13, US, National Income without Capital Consumption Adjustment by Industry, Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates, Billions of Dollars, % of Total

| SAAR IQ2014 | % Total | SAAR | % Total | |

| National Income WCCA | 14,982.0 | 100.0 | 15,276.2 | 100.0 |

| Domestic Industries | 14,771.0 | 98.6 | 15,062.8 | 98.6 |

| Private Industries | 13,055.8 | 87.1 | 13,342.0 | 87.3 |

| Agriculture | 161.0 | 1.1 | 178.6 | 1.2 |

| Mining | 273.1 | 1.8 | 260.5 | 1.7 |

| Utilities | 209.1 | 1.4 | 215.7 | 1.4 |

| Construction | 660.3 | 4.4 | 666.8 | 4.4 |

| Manufacturing | 1642.5 | 11.0 | 1721.4 | 11.3 |

| Durable Goods | 950.2 | 6.3 | 982.0 | 6.4 |

| Nondurable Goods | 692.3 | 4.6 | 739.3 | 4.8 |

| Wholesale Trade | 908.7 | 6.1 | 925.1 | 6.1 |

| Retail Trade | 1029.8 | 6.9 | 1051.9 | 6.9 |

| Transportation & WH | 465.6 | 3.1 | 478.0 | 3.1 |

| Information | 560.5 | 3.7 | 578.0 | 3.8 |

| Finance, Insurance, RE | 2638.0 | 17.6 | 2661.9 | 17.4 |

| Professional & Business Services | 2026.8 | 13.5 | 2086.1 | 13.7 |

| Education, Health Care | 1461.8 | 9.8 | 1487.5 | 9.7 |

| Arts, Entertainment | 593.9 | 4.0 | 605.2 | 4.0 |

| Other Services | 424.7 | 2.8 | 425.4 | 2.8 |

| Government | 1715.1 | 11.4 | 1720.8 | 11.3 |

| Rest of the World | 211.0 | 1.4 | 213.5 | 1.4 |

Notes: SSAR: Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rate; WCCA: Without Capital Consumption Adjustment by Industry; WH: Warehousing; RE, includes rental and leasing: Real Estate; Art, Entertainment includes recreation, accommodation and food services; BS: business services

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Motor vehicle sales and production in the US have been in long-term structural change. Table VA-1 provides the data on new motor vehicle sales and domestic car production in the US from 1990 to 2010. New motor vehicle sales grew from 14,137 thousand in 1990 to the peak of 17,806 thousand in 2000 or 29.5 percent. In that same period, domestic car production fell from 6,231 thousand in 1990 to 5,542 thousand in 2000 or -11.1 percent. New motor vehicle sales fell from 17,445 thousand in 2005 to 11,772 in 2010 or 32.5 percent while domestic car production fell from 4,321 thousand in 2005 to 2,840 thousand in 2010 or 34.3 percent. In Sep 2014, light vehicle sales accumulated to 12,431,305, which is higher by 5.5 percent relative to 11,786,536 a year earlier (http://motorintelligence.com/m_frameset.html). The seasonally adjusted annual rate of light vehicle sales in the US reached 16.43 million in Sep 2014, lower than 17.53 million in Aug 2014 and higher than 15.42 million in Sep 2013 (http://motorintelligence.com/m_frameset.html).

Table VA-1, US, New Motor Vehicle Sales and Car Production, Thousand Units

| New Motor Vehicle Sales | New Car Sales and Leases | New Truck Sales and Leases | Domestic Car Production | |

| 1990 | 14,137 | 9,300 | 4,837 | 6,231 |

| 1991 | 12,725 | 8,589 | 4,136 | 5,454 |

| 1992 | 13,093 | 8,215 | 4,878 | 5,979 |

| 1993 | 14,172 | 8,518 | 5,654 | 5,979 |

| 1994 | 15,397 | 8,990 | 6,407 | 6,614 |

| 1995 | 15,106 | 8,536 | 6,470 | 6,340 |

| 1996 | 15,449 | 8,527 | 6,922 | 6,081 |

| 1997 | 15,490 | 8,273 | 7,218 | 5,934 |

| 1998 | 15,958 | 8,142 | 7,816 | 5,554 |

| 1999 | 17,401 | 8,697 | 8,704 | 5,638 |

| 2000 | 17,806 | 8,852 | 8,954 | 5,542 |

| 2001 | 17,468 | 8,422 | 9,046 | 4,878 |

| 2002 | 17,144 | 8,109 | 9,036 | 5,019 |

| 2003 | 16,968 | 7,611 | 9,357 | 4,510 |

| 2004 | 17,298 | 7,545 | 9,753 | 4,230 |

| 2005 | 17,445 | 7,720 | 9,725 | 4,321 |

| 2006 | 17,049 | 7,821 | 9,228 | 4,367 |

| 2007 | 16,460 | 7,618 | 8,683 | 3,924 |

| 2008 | 13,494 | 6,814 | 6.680 | 3,777 |

| 2009 | 10,601 | 5,456 | 5,154 | 2,247 |

| 2010 | 11,772 | 5,729 | 6,044 | 2,840 |

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/wholesale_retail_trade/motor_vehicle_sales.html

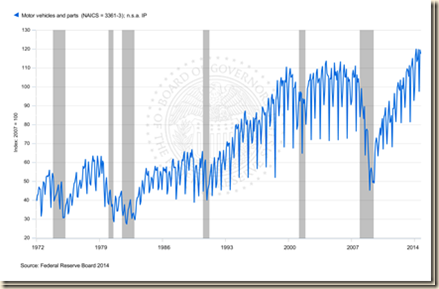

Chart II-5 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve provides output of motor vehicles and parts in the United States from 1972 to 2014. Output virtually stagnated since the late 1990s.

Chart II-5, US, Motor Vehicles and Parts Output, 1972-2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

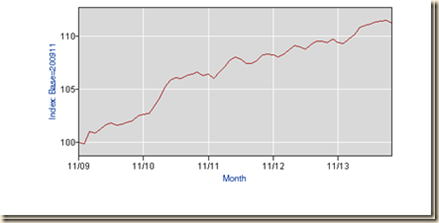

Chart I-6 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides output of computers and electronic products in the United States from 1972 to 2014. Output accelerated sharply in the 1990s and 2000s and has surpassed the level before the global recession beginning in IVQ2007.

Chart I-6, US, Output of Computers and Electronic Products, 1972-2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Chart I-7 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System shows that output of durable manufacturing accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s with slower growth in the 2000s perhaps because processes matured. Growth was robust after the major drop during the global recession but appears to vacillate in the final segment.

Chart I-7, US, Output of Durable Manufacturing, 1972-2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

Chart I-8 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides output of aerospace and miscellaneous transportation equipment from 1972 to 2014. There is long-term upward trend with oscillations around the trend and cycles of large amplitude.

Chart I-8, US, Output of Aerospace and Miscellaneous Transportation Equipment, 1972-2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/default.htm

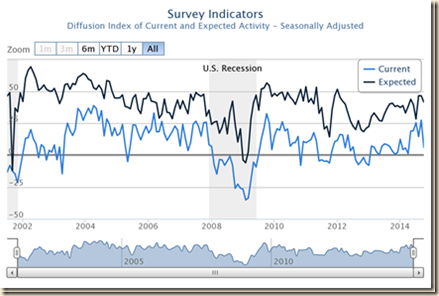

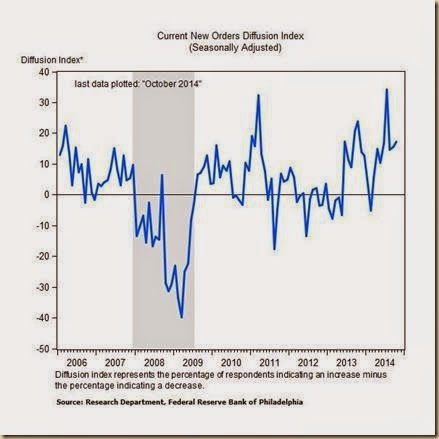

The Empire State Manufacturing Survey Index in Table VA-1 provides continuing deterioration that started in Jun 2012 well before Hurricane Sandy in Oct 2012. The current general index has been in negative contraction territory from minus 3.86 in Aug 2012 to minus 7.93 in Jan 2013 and 0.27 in May 2013. The current general index edged to 6.17 in Oct 2014. The index of current orders has also been in negative contraction territory from minus 3.24 in Aug 2012 to minus 8.48 in Jan 2013 and minus 4.32 in Jun 2013. The index of current new orders decreased to minus 1.73 in Oct 2014. Number of workers and hours worked have registered negative or declining readings since Sep 2012 with weakness to 10.23 for number of workers in Oct 2014 and also minus 1.14 for average workweek. There is improvement in the general index for the next six months at 41.66 in Oct 2014 and strengthening new orders at 42.34.

Table VA-1, US, New York Federal Reserve Bank Empire State Manufacturing Survey Index SA

| Current | General Index | New Orders | Shipments | Number of Workers | Average Workweek |

| Sep-11 | -4.55 | -4.13 | -5.6 | -5.43 | -2.17 |

| Oct-11 | -6.07 | 0.64 | 1.48 | 3.37 | -4.49 |

| Nov-11 | 4.09 | 0.66 | 13.22 | -3.66 | 2.44 |

| Dec-11 | 10.7 | 8.03 | 22.09 | 2.33 | -2.33 |

| Jan-12 | 11.63 | 10.42 | 19.7 | 12.09 | 6.59 |

| Feb-12 | 16.36 | 5.28 | 17.16 | 11.76 | 7.06 |

| Mar-12 | 15.97 | 4.67 | 13.76 | 13.58 | 18.52 |

| Apr-12 | 5.92 | 4.21 | 4.24 | 19.28 | 6.02 |

| May-12 | 15.85 | 9.29 | 22.95 | 20.48 | 12.05 |

| Jun-12 | 3.48 | 4.75 | 11.39 | 12.37 | 3.09 |

| Jul-12 | 6.64 | -2.2 | 11 | 18.52 | 0 |

| Aug-12 | -3.86 | -3.24 | 8.41 | 16.47 | 3.53 |

| Sep-12 | -7.41 | -10.41 | 6.4 | 4.26 | -1.06 |

| Oct-12 | -4.91 | -8.25 | -7.44 | -1.08 | -4.3 |

| Nov-12 | -1.8 | 5.02 | 17.01 | -14.61 | -7.87 |

| Dec-12 | -6.35 | -1.9 | 10.04 | -9.68 | -10.75 |

| Jan-13 | -7.93 | -8.48 | -2.13 | -4.3 | -5.38 |

| Feb-13 | 7.25 | 9.84 | 9.72 | 8.08 | -4.04 |

| Mar-13 | 6.45 | 5.8 | 5.39 | 3.23 | 0 |

| Apr-13 | 2.46 | 1.4 | 0.51 | 6.82 | 5.68 |

| May-13 | 0.27 | -0.67 | -0.36 | 5.68 | -1.14 |

| Jun-13 | 7.09 | -4.32 | -6.3 | 0 | -11.29 |

| Jul-13 | 8.88 | 3.99 | 8.26 | 3.26 | -7.61 |

| Aug-13 | 8.3 | 1.88 | 4 | 10.84 | 4.82 |

| Sep-13 | 6.78 | 2.62 | 15.69 | 7.53 | 1.08 |

| Oct-13 | 3.24 | 6.6 | 12.98 | 3.61 | 3.61 |

| Nov-13 | 0.83 | -3.46 | 1.46 | 0 | -5.26 |

| Dec-13 | 2.22 | -1.69 | 4.69 | 0 | -10.84 |

| Jan-14 | 12.51 | 10.98 | 15.52 | 12.2 | 1.22 |

| Feb-14 | 4.48 | -0.21 | 2.13 | 11.25 | 3.75 |

| Mar-14 | 5.61 | 3.13 | 3.97 | 5.88 | 4.71 |

| Apr-14 | 1.29 | -2.77 | 3.15 | 8.16 | 2.04 |

| May-14 | 19.01 | 10.44 | 17.44 | 20.88 | 2.2 |

| Jun-14 | 19.28 | 18.36 | 14.15 | 10.75 | 9.68 |

| Jul-14 | 25.6 | 18.77 | 23.64 | 17.05 | 2.27 |

| Aug-14 | 14.69 | 14.14 | 24.59 | 13.64 | 7.95 |

| Sep-14 | 27.54 | 16.86 | 27.08 | 3.26 | 3.26 |

| Oct-14 | 6.17 | -1.73 | 1.12 | 10.23 | -1.14 |

| Future | General Index | New Orders | Shipments | Number of Workers | Average Workweek |

| Sep-11 | 22.77 | 23.38 | 22.66 | 0 | -6.52 |

| Oct-11 | 14.41 | 18.95 | 23.42 | 6.74 | -2.25 |

| Nov-11 | 35.91 | 30.35 | 32.7 | 14.63 | 8.54 |