World Inflation Waves, Interest Rate Risks, Squeeze of Economic Activity Induced by Zero Interest Rates, Cyclical Slow Growth not Secular Stagnation, Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation, United States Industrial Production, World Financial Turbulence, World Economic Slowdown and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Executive Summary

I World Inflation Waves

IA Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy

IB1 Theory

IB2 Policy

IB3 Evidence

IB4 Unwinding Strategy

IB United States Inflation

IC Long-term US Inflation

ID Current US Inflation

IE Theory and Reality of Economic History, Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

IB Collapse of United States Dynamism of Income Growth and Employment Creation

II United States Industrial Production

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

Executive Summary

Contents of Executive Summary

ESI Increasing Interest Rate Risk, Tapering Quantitative Easing, Duration Dumping, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk

ESII Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates

ESIII World Inflation Waves

ESIV United States Industrial Production

ESV Theory and Reality of Economic History, Cyclical Slow Growth Not Secular Stagnation and Monetary Policy Based on Fear of Deflation

ESI Increasing Interest Rate Risk, Tapering Quantitative Easing, Duration Dumping, Steepening Yield Curve and Global Financial and Economic Risk. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task for both theory and measurement. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task for both theory and measurement. The IMF (2013WEOOct) provides surveillance of the world economy with its Global Economic Outlook (WEO) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/), of the world financial system with its Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) (IMF 2013GFSROct) (http://www.imf.org/External/Pubs/FT/GFSR/2013/02/index.htm) and of fiscal affairs with the Fiscal Monitor (IMF 2013FMOct) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2013/02/fmindex.htm). There appears to be a moment of transition in global economic and financial variables that may prove of difficult analysis and measurement. It is useful to consider a summary of global economic and financial risks, which are analyzed in detail in the comments of this blog in Section VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets, Table VI-4.

Economic risks include the following:

- China’s Economic Growth. China is lowering its growth target to 7.5 percent per year. China’s GDP growth decelerated significantly from annual equivalent 10.8 percent in IIQ2011 to 7.4 percent in IVQ2011 and 5.7 percent in IQ2012, rebounding to 9.1 percent in IIQ2012, 8.2 percent in IIIQ2012 and 7.8 percent in IVQ2012. Annual equivalent growth in IQ2013 fell to 6.1 percent and to 7.8 percent in IIQ2013, rebounding to 9.1 percent in IIIQ2013 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/07/tapering-quantitative-easing-policy-and_7005.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/recovery-without-hiring-world-inflation.html and earlier at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/10/world-inflation-waves-stagnating-united_21.html).

- United States Economic Growth, Labor Markets and Budget/Debt Quagmire. The US is growing slowly with 28.1 million in job stress, fewer 10 million full-time jobs, high youth unemployment, historically low hiring and declining/stagnating real wages.

- Economic Growth and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies. Advanced economies are growing slowly. There is still high unemployment in advanced economies.

- World Inflation Waves. Inflation continues in repetitive waves globally (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/tapering-quantitative-easing-mediocre.html).

A list of financial uncertainties includes:

- Euro Area Survival Risk. The resilience of the euro to fiscal and financial doubts on larger member countries is still an unknown risk.

- Foreign Exchange Wars. Exchange rate struggles continue as zero interest rates in advanced economies induce devaluation of their currencies.

- Valuation of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with lower volumes.

- Duration Trap of the Zero Bound. The yield of the US 10-year Treasury rose from 2.031 percent on Mar 9, 2012, to 2.294 percent on Mar 16, 2012. Considering a 10-year Treasury with coupon of 2.625 percent and maturity in exactly 10 years, the price would fall from 105.3512 corresponding to yield of 2.031 percent to 102.9428 corresponding to yield of 2.294 percent, for loss in a week of 2.3 percent but far more in a position with leverage of 10:1. Min Zeng, writing on “Treasurys fall, ending brutal quarter,” published on Mar 30, 2012, in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303816504577313400029412564.html?mod=WSJ_hps_sections_markets), informs that Treasury bonds maturing in more than 20 years lost 5.52 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

- Credibility and Commitment of Central Bank Policy. There is a credibility issue of the commitment of monetary policy (Sargent and Silber 2012Mar20).

- Carry Trades. Commodity prices driven by zero interest rates have resumed their increasing path with fluctuations caused by intermittent risk aversion

Chart VIII-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the rate on the overnight fed funds rate and the yields of the 10-year constant maturity Treasury and the Baa seasoned corporate bond. Table VIII-3 provides the data for selected points in Chart VIII-1. There are two important economic and financial events, illustrating the ease of inducing carry trade with extremely low interest rates and the resulting financial crash and recession of abandoning extremely low interest rates.

- The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target of the fed funds rate from 7.03 percent on Jul 3, 2000, to 1.00 percent on Jun 22, 2004, in pursuit of non-existing deflation (Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 18-28, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 83-85). Central bank commitment to maintain the fed funds rate at 1.00 percent induced adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMS) linked to the fed funds rate. Lowering the interest rate near the zero bound in 2003-2004 caused the illusion of permanent increases in wealth or net worth in the balance sheets of borrowers and also of lending institutions, securitized banking and every financial institution and investor in the world. The discipline of calculating risks and returns was seriously impaired. The objective of monetary policy was to encourage borrowing, consumption and investment. The exaggerated stimulus resulted in a financial crisis of major proportions as the securitization that had worked for a long period was shocked with policy-induced excessive risk, imprudent credit, high leverage and low liquidity by the incentive to finance everything overnight at interest rates close to zero, from adjustable rate mortgages (ARMS) to asset-backed commercial paper of structured investment vehicles (SIV). The consequences of inflating liquidity and net worth of borrowers were a global hunt for yields to protect own investments and money under management from the zero interest rates and unattractive long-term yields of Treasuries and other securities. Monetary policy distorted the calculations of risks and returns by households, business and government by providing central bank cheap money. Short-term zero interest rates encourage financing of everything with short-dated funds, explaining the SIVs created off-balance sheet to issue short-term commercial paper with the objective of purchasing default-prone mortgages that were financed in overnight or short-dated sale and repurchase agreements (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 50-1, Regulation of Banks and Finance, 59-60, Globalization and the State Vol. I, 89-92, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 198-9, Government Intervention in Globalization, 62-3, International Financial Architecture, 144-9). ARMS were created to lower monthly mortgage payments by benefitting from lower short-dated reference rates. Financial institutions economized in liquidity that was penalized with near zero interest rates. There was no perception of risk because the monetary authority guaranteed a minimum or floor price of all assets by maintaining low interest rates forever or equivalent to writing an illusory put option on wealth. Subprime mortgages were part of the put on wealth by an illusory put on house prices. The housing subsidy of $221 billion per year created the impression of ever-increasing house prices. The suspension of auctions of 30-year Treasuries was designed to increase demand for mortgage-backed securities, lowering their yield, which was equivalent to lowering the costs of housing finance and refinancing. Fannie and Freddie purchased or guaranteed $1.6 trillion of nonprime mortgages and worked with leverage of 75:1 under Congress-provided charters and lax oversight. The combination of these policies resulted in high risks because of the put option on wealth by near zero interest rates, excessive leverage because of cheap rates, low liquidity by the penalty in the form of low interest rates and unsound credit decisions. The put option on wealth by monetary policy created the illusion that nothing could ever go wrong, causing the credit/dollar crisis and global recession (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession, 157-66, Regulation of Banks, and Finance, 217-27, International Financial Architecture, 15-18, The Global Recession Risk, 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II, 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization, 182-4). The FOMC implemented increments of 25 basis points of the fed funds target from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006, raising the fed funds rate to 5.25 percent on Jul 3, 2006, as shown in Chart VIII-1. The gradual exit from the first round of unconventional monetary policy from 1.00 percent in Jun 2004 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/monetary/2004/20040630/default.htm) to 5.25 percent in Jun 2006 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20060629a.htm) caused the financial crisis and global recession.

- On Dec 16, 2008, the policy determining committee of the Fed decided (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm): “The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to establish a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent.” Policymakers emphasize frequently that there are tools to exit unconventional monetary policy at the right time. At the confirmation hearing on nomination for Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Vice Chair Yellen (2013Nov14 http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20131114a.htm), states that: “The Federal Reserve is using its monetary policy tools to promote a more robust recovery. A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases. I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.” Perception of withdrawal of $2560 billion, or $2.6 trillion, of bank reserves (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1), would cause Himalayan increase in interest rates that would provoke another recession. There is no painless gradual or sudden exit from zero interest rates because reversal of exposures created on the commitment of zero interest rates forever.

In his classic restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958, 86):

“The assumption that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates and differ from each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969) provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus, g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Friedman 1957). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

Chart VIII-1, Fed Funds Rate and Yields of Ten-year Treasury Constant Maturity and Baa Seasoned Corporate Bond, Jan 2, 2001 to Jan 16, 2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Table VIII-3, Selected Data Points in Chart VIII-1, % per Year

| Fed Funds Overnight Rate | 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity | Seasoned Baa Corporate Bond | |

| 1/2/2001 | 6.67 | 4.92 | 7.91 |

| 10/1/2002 | 1.85 | 3.72 | 7.46 |

| 7/3/2003 | 0.96 | 3.67 | 6.39 |

| 6/22/2004 | 1.00 | 4.72 | 6.77 |

| 6/28/2006 | 5.06 | 5.25 | 6.94 |

| 9/17/2008 | 2.80 | 3.41 | 7.25 |

| 10/26/2008 | 0.09 | 2.16 | 8.00 |

| 10/31/2008 | 0.22 | 4.01 | 9.54 |

| 4/6/2009 | 0.14 | 2.95 | 8.63 |

| 4/5/2010 | 0.20 | 4.01 | 6.44 |

| 2/4/2011 | 0.17 | 3.68 | 6.25 |

| 7/25/2012 | 0.15 | 1.43 | 4.73 |

| 5/1/13 | 0.14 | 1.66 | 4.48 |

| 9/5/13 | 0.08 | 2.98 | 5.53 |

| 11/21/2013 | 0.09 | 2.79 | 5.44 |

| 11/27/13 | 0.09 | 2.74 | 5.34 (11/26/13) |

| 12/6/13 | 0.09 | 2.88 | 5.47 |

| 12/12/13 | 0.09 | 2.89 | 5.42 |

| 12/19/13 | 0.09 | 2.94 | 5.36 |

| 12/26/13 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.37 |

| 1/2/2014 | 0.08 | 3.00 | 5.34 |

| 1/9/2014 | 0.07 | 2.97 | 5.28 |

| 1/16/2014 | 0.07 | 2.86 | 5.18 |

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Professionals use a variety of techniques in measuring interest rate risk (Fabozzi, Buestow and Johnson, 2006, Chapter Nine, 183-226):

- Full valuation approach in which securities and portfolios are shocked by 50, 100, 200 and 300 basis points to measure their impact on asset values

- Stress tests requiring more complex analysis and translation of possible events with high impact even if with low probability of occurrence into effects on actual positions and capital

- Value at Risk (VaR) analysis of maximum losses that are likely in a time horizon

- Duration and convexity that are short-hand convenient measurement of changes in prices resulting from changes in yield captured by duration and convexity

- Yield volatility

Analysis of these methods is in Pelaez and Pelaez (International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-162) and Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. (I) (2008a), 78-100). Frederick R. Macaulay (1938) introduced the concept of duration in contrast with maturity for analyzing bonds. Duration is the sensitivity of bond prices to changes in yields. In economic jargon, duration is the yield elasticity of bond price to changes in yield, or the percentage change in price after a percentage change in yield, typically expressed as the change in price resulting from change of 100 basis points in yield. The mathematical formula is the negative of the yield elasticity of the bond price or –[dB/d(1+y)]((1+y)/B), where d is the derivative operator of calculus, B the bond price, y the yield and the elasticity does not have dimension (Hallerbach 2001). The duration trap of unconventional monetary policy is that duration is higher the lower the coupon and higher the lower the yield, other things being constant. Coupons and yields are historically low because of unconventional monetary policy. Duration dumping during a rate increase may trigger the same crossfire selling of high duration positions that magnified the credit crisis. Traders reduced positions because capital losses in one segment, such as mortgage-backed securities, triggered haircuts and margin increases that reduced capital available for positioning in all segments, causing fire sales in multiple segments (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2008b), 217-24). Financial markets are currently experiencing fear of duration resulting from the debate within and outside the Fed on tapering quantitative easing. Table VIII-2 provides the yield curve of Treasury securities on Jan 17, 2014, Dec 31, 2013, May 1, 2013, Jan 17, 2013 and Jan 17, 2006. There is ongoing steepening of the yield curve for longer maturities, which are also the ones with highest duration. The 10-year yield increased from 1.45 percent on Jul 26, 2012 to 3.04 percent on Dec 31, 2013 and 2.84 percent on Jan 17, 2014, as measured by the United States Treasury. Assume that a bond with maturity in 10 years were issued on Dec 31, 2013, at par or price of 100 with coupon of 1.45 percent. The price of that bond would be 86.3778 with instantaneous increase of the yield to 3.04 percent for loss of 13.6 percent and far more with leverage. Assume that the yield of a bond with exactly ten years to maturity and coupon of 2.84 percent as occurred on Jan 17, 2013 would jump instantaneously from yield of 2.84 percent on Jan 17, 2014 to 4.34 percent as occurred on Jan 17, 2006 when the economy was closer to full employment. The price of the hypothetical bond issued with coupon of 2.84 percent would drop from 100 to 87.9353 after an instantaneous increase of the yield to 4.34 percent. The price loss would be 12.1 percent. Losses absorb capital available for positioning, triggering crossfire sales in multiple asset classes (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009). What is the path of adjustment of zero interest rates on fed funds and artificially low bond yields? There is no painless exit from unconventional monetary policy. Chris Dieterich, writing on “Bond investors turn to cash,” on Jul 25, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323971204578625900935618178.html), uses data of the Investment Company Institute (http://www.ici.org/) in showing withdrawals of $43 billion in taxable mutual funds in Jun, which is the largest in history, with flows into cash investments such as $8.5 billion in the week of Jul 17 into money-market funds.

Table VIII-2, United States, Treasury Yields

| 1/17/14 | 12/31/13 | 5/01/13 | 1/17/13 | 1/10/06 | |

| 1 M | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 4.11 |

| 3 M | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 4.38 |

| 6 M | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 4.47 |

| 1 Y | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 4.42 |

| 2 Y | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 4.33 |

| 3 Y | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 4.28 |

| 5 Y | 1.64 | 1.75 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 4.27 |

| 7 Y | 2.27 | 2.45 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 4.29 |

| 10 Y | 2.84 | 3.04 | 1.66 | 1.89 | 4.34 |

| 20 Y | 3.50 | 3.72 | 2.44 | 2.66 | 4.57 |

| 30 Y | 3.75 | 3.96 | 2.83 | 3.06 | NA |

Source: United States Treasury

Interest rate risk is increasing in the US. Chart VI-13 of the Board of Governors provides the conventional mortgage rate for a fixed-rate 30-year mortgage. The rate stood at 5.87 percent on Jan 8, 2004, increasing to 6.79 percent on Jul 6, 2006. The rate bottomed at 3.35 percent on May 2, 2013. Fear of duration risk in longer maturities such as mortgage-backed securities caused continuing increases in the conventional mortgage rate that rose to 4.51 percent on Jul 11, 2013, 4.58 percent on Aug 22, 2013 and 4.41 percent on Jan 16, 2014, which is the last data point in Chart VI-13. Shayndi Raice and Nick Timiraos, writing on “Banks cut as mortgage boom ends,” on Jan 9, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303754404579310940019239208), analyze the drop in mortgage applications to a 13-year low, as measured by the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Chart VI-13, US, Conventional Mortgage Rate, Jan 8, 2004 to Jan 16, 2014

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/update/

The major reason and channel of transmission of unconventional monetary policy is through expectations of inflation. Fisher (1930) provided theoretical and historical relation of interest rates and inflation. Let in be the nominal interest rate, ir the real or inflation-adjusted interest rate and πe the expectation of inflation in the time term of the interest rate, which are all expressed as proportions. The following expression provides the relation of real and nominal interest rates and the expectation of inflation:

(1 + ir) = (1 + in)/(1 + πe) (1)

That is, the real interest rate equals the nominal interest rate discounted by the expectation of inflation in time term of the interest rate. Fisher (1933) analyzed the devastating effect of deflation on debts. Nominal debt contracts remained at original principal interest but net worth and income of debtors contracted during deflation. Real interest rates increase during declining inflation. For example, if the interest rate is 3 percent and prices decline 0.2 percent, equation (1) calculates the real interest rate as:

(1 +0.03)/(1 – 0.02) = 1.03/(0.998) = 1.032

That is, the real rate of interest is (1.032 – 1) 100 or 3.2 percent. If inflation were 2 percent, the real rate of interest would be 0.98 percent, or about 1.0 percent {[(1.03/1.02) -1]100 = 0.98%}.

The yield of the one-year Treasury security was quoted in the Wall Street Journal at 0.114 percent on Fri May 17, 2013 (http://online.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_topnav_marketdata_main). The expected rate of inflation πe in the next twelve months is not observed. Assume that it would be equal to the rate of inflation in the past twelve months estimated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BLS) at 1.1 percent (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/). The real rate of interest would be obtained as follows:

(1 + 0.00114)/(1 + 0.011) = (1 + rr) = 0.9902

That is, ir is equal to 1 – 0.9902 or minus 0.98 percent. Investing in a one-year Treasury security results in a loss of 0.98 percent relative to inflation. The objective of unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates is to induce consumption and investment because of the loss to inflation of riskless financial assets. Policy would be truly irresponsible if it intended to increase inflationary expectations or πe. The result could be the same rate of unemployment with higher inflation (Kydland and Prescott 1977).

Current focus is on tapering quantitative easing by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). There is sharp distinction between the two measures of unconventional monetary policy: (1) fixing of the overnight rate of fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent; and (2) outright purchase of Treasury and agency securities and mortgage-backed securities for the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. Market are overreacting to the so-called “paring” of outright purchases of $85 billion of securities per month for the balance sheet of the Fed (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20131218a.htm):

“In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions, the Committee decided to modestly reduce the pace of its asset purchases. Beginning in January, the Committee will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $35 billion per month rather than $40 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $40 billion per month rather than $45 billion per month. The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. The Committee's sizable and still-increasing holdings of longer-term securities should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative, which in turn should promote a stronger economic recovery and help to ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with the Committee's dual mandate.”

What is truly important is the fixing of the overnight fed funds at 0 to ¼ percent for which there is no end in sight as evident in the FOMC statement for Dec 18, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20131218a.htm):

“To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens. The Committee also reaffirmed its expectation that the current exceptionally low target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee's 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored (emphasis added).

There is a critical phrase in the statement of Sep 19, 2013 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20130918a.htm): “but mortgage rates have risen further.” Did the increase of mortgage rates influence the decision of the FOMC not to taper? Is FOMC “communication” and “guidance” successful? Will the FOMC increase purchases of mortgage-backed securities if mortgage rates increase?

At the confirmation hearing on nomination for Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Vice Chair Yellen (2013Nov14 http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/yellen20131114a.htm), states needs and intentions of policy:

“We have made good progress, but we have farther to go to regain the ground lost in the crisis and the recession. Unemployment is down from a peak of 10 percent, but at 7.3 percent in October, it is still too high, reflecting a labor market and economy performing far short of their potential. At the same time, inflation has been running below the Federal Reserve's goal of 2 percent and is expected to continue to do so for some time.

For these reasons, the Federal Reserve is using its monetary policy tools to promote a more robust recovery. A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases. I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy.”

In his classic restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958, 86):

“The assumption that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates and differfrom each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969) provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus, g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory, “income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957, 10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return, r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Ibid). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W. This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby 1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r (10

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

The argument that anemic population growth causes “secular stagnation” in the US (Hansen 1938, 1939, 1941) is as misplaced currently as in the late 1930s (for early dissent see Simons 1942). There is currently population growth in the ages of 16 to 24 years but not enough job creation and discouragement of job searches for all ages (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/theory-and-reality-of-secular.html). This is merely another case of theory without reality with dubious policy proposals. The current reality is cyclical slow growth.

In delivering the biannual report on monetary policy (Board of Governors 2013Jul17), Chairman Bernanke (2013Jul17) advised Congress that:

“Instead, we are providing additional policy accommodation through two distinct yet complementary policy tools. The first tool is expanding the Federal Reserve's portfolio of longer-term Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS); we are currently purchasing $40 billion per month in agency MBS and $45 billion per month in Treasuries. We are using asset purchases and the resulting expansion of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet primarily to increase the near-term momentum of the economy, with the specific goal of achieving a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market in a context of price stability. We have made some progress toward this goal, and, with inflation subdued, we intend to continue our purchases until a substantial improvement in the labor market outlook has been realized. We are relying on near-zero short-term interest rates, together with our forward guidance that rates will continue to be exceptionally low--our second tool--to help maintain a high degree of monetary accommodation for an extended period after asset purchases end, even as the economic recovery strengthens and unemployment declines toward more-normal levels. In appropriate combination, these two tools can provide the high level of policy accommodation needed to promote a stronger economic recovery with price stability.

The Committee's decisions regarding the asset purchase program (and the overall stance of monetary policy) depend on our assessment of the economic outlook and of the cumulative progress toward our objectives. Of course, economic forecasts must be revised when new information arrives and are thus necessarily provisional.”

Friedman (1953) argues there are three lags in effects of monetary policy: (1) between the need for action and recognition of the need; (2) the recognition of the need and taking of actions; and (3) taking of action and actual effects. Friedman (1953) finds that the combination of these lags with insufficient knowledge of the current and future behavior of the economy causes discretionary economic policy to increase instability of the economy or standard deviations of real income σy and prices σp. Policy attempts to circumvent the lags by policy impulses based on forecasts. We are all naïve about forecasting. Data are available with lags and revised to maintain high standards of estimation. Policy simulation models estimate economic relations with structures prevailing before simulations of policy impulses such that parameters change as discovered by Lucas (1977). Economic agents adjust their behavior in ways that cause opposite results from those intended by optimal control policy as discovered by Kydland and Prescott (1977). Advance guidance attempts to circumvent expectations by economic agents that could reverse policy impulses but is of dubious effectiveness. There is strong case for using rules instead of discretionary authorities in monetary policy (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/search?q=rules+versus+authorities).

The key policy is maintaining fed funds rate between 0 and ¼ percent. An increase in fed funds rates could cause flight out of risk financial markets worldwide. There is no exit from this policy without major financial market repercussions. Indefinite financial repression induces carry trades with high leverage, risks and illiquidity. A competing event is the high level of valuations of risk financial assets (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/01/peaking-valuation-of-risk-financial.html). Matt Jarzemsky, writing on “Dow industrials set record,” on Mar 5, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324156204578275560657416332.html), analyzes that the DJIA broke the closing high of 14,164.53 set on Oct 9, 2007, and subsequently also broke the intraday high of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. The DJIA closed at 16,458.56 on Fri Jan 17, 2014, which is higher by 16.2 percent than the value of 14,164.53 reached on Oct 9, 2007 and higher by 15.9 percent than the value of 14,198.10 reached on Oct 11, 2007. Values of risk financial are approaching or exceeding historical highs.

Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “Jobs upturn isn’t enough to satisfy Fed,” on Mar 8, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324582804578348293647760204.html), finds that much stronger labor market conditions are required for the Fed to end quantitative easing. Unconventional monetary policy with zero interest rates and quantitative easing is quite difficult to unwind because of the adverse effects of raising interest rates on valuations of risk financial assets and home prices, including the very own valuation of the securities held outright in the Fed balance sheet. Gradual unwinding of 1 percent fed funds rates from Jun 2003 to Jun 2004 by seventeen consecutive increases of 25 percentage points from Jun 2004 to Jun 2006 to reach 5.25 percent caused default of subprime mortgages and adjustable-rate mortgages linked to the overnight fed funds rate. The zero interest rate has penalized liquidity and increased risks by inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to speculative positions in risk financial assets. There is no exit from zero interest rates without provoking another financial crash.

The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets had proved strongest for commodity exposures but US equities have regained leadership. The DJIA has increased 69.9 percent since the trough of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe on Jul 2, 2010 to Jan 17, 2014; S&P 500 has gained 79.8 percent and DAX 71.8 percent. Before the current round of risk aversion, almost all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 1/17/14” had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010 followed by negative performance but now some valuations of equity indexes show varying behavior. China’s Shanghai Composite is 15.9 percent below the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 78.3 percent above the trough. DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 25.6 percent above the trough. Dow Global is 46.1 percent above the trough. STOXX 50 of 50 blue-chip European equities (http://www.stoxx.com/indices/index_information.html?symbol=sx5E) is 29.7 percent above the trough. NYSE Financial Index is 49.9 percent above the trough. DJ UBS Commodities is 0.9 percent above the trough. DAX index of German equities (http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/DAX:IND) is 71.8 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 78.3 percent above the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 38.1 percent above the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 15,734.46 on Fri Jan 17, 2014 (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata), which is 53.4 percent higher than 10,254.43 on Mar 11, 2011, on the date of the Tōhoku or Great East Japan Earthquake/tsunami. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar depreciated by 13.6 percent relative to the euro and even higher before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 1/17/14” in Table VI-4 shows decrease of 0.4 percent in the week for China’s Shanghai Composite. DJ Asia Pacific changed 0.0 percent. NYSE Financial decreased 0.2 percent in the week. DJ UBS Commodities increased 1.2 percent. Dow Global increased 0.5 percent in the week of Jan 17, 2014. The DJIA increased 0.1 percent and S&P 500 decreased 0.2 percent. DAX of Germany increased 2.8 percent. STOXX 50 increased 1.9 percent. The USD appreciated 0.9 percent. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks and banking soundness, US and world growth slowdown and China’s growth tradeoffs. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table VI-4 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 1/17/14” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Jan 17, 2014. Most risk financial assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 1/17/14” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 1/17/14.” There are now several equity indexes above the peak in Table VI-4: DJIA 46.9 percent, S&P 500 51.0 percent, DAX 53.9 percent, Dow Global 19.2 percent, DJ Asia Pacific 9.9 percent, NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) 19.4 percent, Nikkei Average 38.1 percent and STOXX 50 9.8 percent. There is only one equity index below the peak: Shanghai Composite by 36.7 percent. DJ UBS Commodities Index is now 13.7 percent below the peak. The US dollar strengthened 10.5 percent relative to the peak. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr 2010 is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul 2010 because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. Alexandra Scaggs, writing on “Tepid profits, roaring stocks,” on May 16, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323398204578487460105747412.html), analyzes stabilization of earnings growth: 70 percent of 458 reporting companies in the S&P 500 stock index reported earnings above forecasts but sales fell 0.2 percent relative to forecasts of increase of 0.5 percent. Paul Vigna, writing on “Earnings are a margin story but for how long,” on May 17, 2013, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/05/17/earnings-are-a-margin-story-but-for-how-long/), analyzes that corporate profits increase with stagnating sales while companies manage costs tightly. More than 90 percent of S&P components reported moderate increase of earnings of 3.7 percent in IQ2013 relative to IQ2012 with decline of sales of 0.2 percent. Earnings and sales have been in declining trend. In IVQ2009, growth of earnings reached 104 percent and sales jumped 13 percent. Net margins reached 8.92 percent in IQ2013, which is almost the same at 8.95 percent in IIIQ2006. Operating margins are 9.58 percent. There is concern by market participants that reversion of margins to the mean could exert pressure on earnings unless there is more accelerated growth of sales. Vigna (op. cit.) finds sales growth limited by weak economic growth. Kate Linebaugh, writing on “Falling revenue dings stocks,” on Oct 20, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444592704578066933466076070.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), identifies a key financial vulnerability: falling revenues across markets for United States reporting companies. Global economic slowdown is reducing corporate sales and squeezing corporate strategies. Linebaugh quotes data from Thomson Reuters that 100 companies of the S&P 500 index have reported declining revenue only 1 percent higher in Jun-Sep 2012 relative to Jun-Sep 2011 but about 60 percent of the companies are reporting lower sales than expected by analysts with expectation that revenue for the S&P 500 will be lower in Jun-Sep 2012 for the entities represented in the index. Results of US companies are likely repeated worldwide. Future company cash flows derive from investment projects. In IQ1980, gross private domestic investment in the US was $951.6 billion of 2009 dollars, growing to $1,143.0 billion in IVQ1986 or 20.1 percent. Real gross private domestic investment in the US increased 0.8 percent from $2,605.2 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,627.2 billion in IIIQ2013. As shown in Table IAI-2, real private fixed investment fell 3.6 percent from $2,586.3 billion of 2009 dollars in IVQ2007 to $2,494.0 billion in IIIQ2013. Growth of real private investment is mediocre for all but four quarters from IIQ2011 to IQ2012 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/11/global-financial-risk-mediocre-united.html). The investment decision of United States corporations has been fractured in the current economic cycle in preference of cash. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA fell $26.6 billion in IQ2013 after increasing $34.9 billion in IVQ2012 and $13.9 billion in IIIQ2012. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA rebounded with $66.8 billion in IIQ2013 and $39.2 billion in IIIQ2013. Profits after tax with IVA and CCA fell $1.7 billion in IQ2013 after increasing $40.8 billion in IVQ2012 and $4.5 billion in IIIQ2012. In IIQ2013, profits after tax with IVA and CCA increased $56.9 billion and $39.5 billion in IIIQ2013. Anticipation of higher taxes in the “fiscal cliff” episode caused increase of $120.9 billion in net dividends in IVQ2012 followed with adjustment in the form of decrease of net dividends by $103.8 billion in IQ2013, rebounding with $273.5 billion in IIQ2013. Net dividends fell at $179.0 billion in IIIQ2013. There is similar decrease of $80.1 billion in undistributed profits with IVA and CCA in IVQ2012 followed by increase of $102.1 billion in IQ2013 and decline of $216.6 billion in IIQ2013. Undistributed profits with IVA and CCA rose at $218.6 billion in IIIQ2013. Undistributed profits of US corporations swelled 382.4 percent from $107.7 billion IQ2007 to $519.5 billion in IIIQ2013 and changed signs from minus $55.9 billion in billion in IVQ2007 (Section IA2). In IQ2013, corporate profits with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustment fell $26.6 billion relative to IVQ2012, from $2047.2 billion to $2020.6 billion at the quarterly rate of minus 1.3 percent. In IIQ2013, corporate profits with IVA and CCA increased $66.8 billion from $2020.6 billion in IQ2013 to $2087.4 billion at the quarterly rate of 3.3 percent. Corporate profits with IVA and CCA increased $39.2 billion from $2087.4 billion in IIQ2013 to $2126.6 billion in IIIQ2013 at the annual rate of 1.9 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp3q13_3rd.pdf). Uncertainty originating in fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy causes wide swings in expectations and decisions by the private sector with adverse effects on investment, real economic activity and employment. Uncertainty originating in fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy causes wide swings in expectations and decisions by the private sector with adverse effects on investment, real economic activity and employment. The investment decision of US business is fractured. The basic valuation equation that is also used in capital budgeting postulates that the value of stocks or of an investment project is given by:

Where Rτ is expected revenue in the time horizon from τ =1 to T; Cτ denotes costs; and ρ is an appropriate rate of discount. In words, the value today of a stock or investment project is the net revenue, or revenue less costs, in the investment period from τ =1 to T discounted to the present by an appropriate rate of discount. In the current weak economy, revenues have been increasing more slowly than anticipated in investment plans. An increase in interest rates would affect discount rates used in calculations of present value, resulting in frustration of investment decisions. If V represents value of the stock or investment project, as ρ → ∞, meaning that interest rates increase without bound, then V → 0, or

declines. Equally, decline in expected revenue from the stock or project, Rτ, causes decline in valuation. An intriguing issue is the difference in performance of valuations of risk financial assets and economic growth and employment. Paul A. Samuelson (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1970/samuelson-bio.html) popularized the view of the elusive relation between stock markets and economic activity in an often-quoted phrase “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” In the presence of zero interest rates forever, valuations of risk financial assets are likely to differ from the performance of the overall economy. The interrelations of financial and economic variables prove difficult to analyze and measure.

Table VI-4, Stock Indexes, Commodities, Dollar and 10-Year Treasury

| Peak | Trough | ∆% to Trough | ∆% Peak to 1/17/ /14 | ∆% Week 1/17/14 | ∆% Trough to 1/17/ 14 | |

| DJIA | 4/26/ | 7/2/10 | -13.6 | 46.9 | 0.1 | 69.9 |

| S&P 500 | 4/23/ | 7/20/ | -16.0 | 51.0 | -0.2 | 79.8 |

| NYSE Finance | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -20.3 | 19.4 | -0.2 | 49.9 |

| Dow Global | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -18.4 | 19.2 | 0.5 | 46.1 |

| Asia Pacific | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -12.5 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 25.6 |

| Japan Nikkei Aver. | 4/05/ | 8/31/ | -22.5 | 38.1 | -1.1 | 78.3 |

| China Shang. | 4/15/ | 7/02 | -24.7 | -36.7 | -0.4 | -15.9 |

| STOXX 50 | 4/15/10 | 7/2/10 | -15.3 | 9.8 | 1.9 | 29.7 |

| DAX | 4/26/ | 5/25/ | -10.5 | 53.9 | 2.8 | 71.8 |

| Dollar | 11/25 2009 | 6/7 | 21.2 | 10.5 | 0.9 | -13.6 |

| DJ UBS Comm. | 1/6/ | 7/2/10 | -14.5 | -13.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| 10-Year T Note | 4/5/ | 4/6/10 | 3.986 | 2.784 | 2.818 |

T: trough; Dollar: positive sign appreciation relative to euro (less dollars paid per euro), negative sign depreciation relative to euro (more dollars paid per euro)

Source: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

ESII Squeeze of Economic Activity by Carry Trades Induced by Zero Interest Rates. Long-term economic growth in Japan significantly improved by increasing competitiveness in world markets. Net trade of exports and imports is an important component of the GDP accounts of Japan. Table VB-3 provides quarterly data for net trade, exports and imports of Japan. Net trade had strong positive contributions to GDP growth in Japan in all quarters from IQ2007 to IIQ2009 with exception of IVQ2008, IIIQ2008 and IQ2009. The US recession is dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) as beginning in IVQ2007 (Dec) and ending in IIQ2009 (Jun) (http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html). Net trade contributions helped to cushion the economy of Japan from the global recession. Net trade deducted from GDP growth in seven of the nine quarters from IVQ2010 IQ2012. The only strong contribution of net trade was 3.9 percent in IIIQ2011. Net trade added 1.6 percentage points to GDP growth in IQ2013 and 0.6 percentage points in IIQ2013 but deducted 1.9 percentage points in IIIQ2013. Private consumption assumed the role of driver of Japan’s economic growth but should moderate as in most mature economies.

Table VB-3, Japan, Contributions to Changes in Real GDP, Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rates (SAAR), %

| Net Trade | Exports | Imports | |

| 2013 | |||

| I | 1.6 | 2.2 | -0.7 |

| II | 0.6 | 1.7 | -1.1 |

| III | -1.9 | -0.4 | -1.5 |

| 2012 | |||

| I | 0.4 | 1.6 | -1.2 |

| II | -1.3 | -0.3 | -1.0 |

| III | -2.1 | -2.3 | 0.2 |

| IV | -0.6 | -1.8 | 1.2 |

| 2011 | |||

| I | -1.2 | -0.5 | -0.7 |

| II | -4.3 | -4.7 | 0.4 |

| III | 3.9 | 5.8 | -1.9 |

| IV | -3.1 | -1.9 | -1.2 |

| 2010 | |||

| I | 2.1 | 3.4 | -1.3 |

| II | 0.1 | 2.7 | -2.6 |

| III | 0.5 | 1.4 | -0.9 |

| IV | -0.5 | 0.1 | -0.5 |

| 2009 | |||

| I | -4.4 | -16.4 | 12.0 |

| II | 7.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| III | 2.2 | 5.2 | -3.0 |

| IV | 2.7 | 4.1 | -1.4 |

| 2008 | |||

| I | 1.1 | 2.1 | -1.0 |

| II | 0.5 | -1.6 | 2.1 |

| III | 0.0 | 0.2 | -0.1 |

| IV | -11.5 | -10.2 | -1.3 |

| 2007 | |||

| I | 1.1 | 1.7 | -0.5 |

| II | 0.8 | 1.6 | -0.8 |

| III | 2.0 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| IV | 1.4 | 2.1 | -0.7 |

Source: Japan Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/index-e.html

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/sokuhou/sokuhou_top.html

There was milder increase in Japan’s export corporate goods price index during the global recession in 2008 but similar sharp decline during the bank balance sheets effect in late 2008, as shown in Chart IV-7 of the Bank of Japan. Japan exports industrial goods whose prices have been less dynamic than those of commodities and raw materials. As a result, the export CGPI on the yen basis in Chart IV-7 trends down with oscillations after a brief rise in the final part of the recession in 2009. The export corporate goods price index on the yen basis fell from 104.9 in Jun 2009 to 94.0 in Jan 2012 or minus 10.4 percent and increased to 110.2 in Dec 2013 for a gain of 17.2 percent relative to Jan 2012 and 5.1 percent relative to Jun 2009. The choice of Jun 2009 is designed to capture the reversal of risk aversion beginning in Sep 2008 with the announcement of toxic assets in banks that would be withdrawn with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) (Cochrane and Zingales 2009). Reversal of risk aversion in the form of flight to the USD and obligations of the US government opened the way to renewed carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in risk financial assets such as commodities. Japan exports industrial products and imports commodities and raw materials.

Chart IV-7, Japan, Export Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Yen Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Chart IV-7A provides the export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency. The export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased from 97.9 in Jun 2009 to 103.1 in Apr 2012 or 5.3 percent but dropped to 100.2 in Apr 2013 or minus 2.8 percent relative to Apr 2012 and gained 1.0 percent to 98.9 in Dec 2013 relative to Jun 2009.

Chart IV-7A, Japan, Export Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Contract Currency Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Japan imports primary commodities and raw materials. As a result, the import corporate goods price index on the yen basis in Chart IV-8 shows an upward trend after declining from the increase during the global recession in 2008 driven by carry trades from fed funds rates. The index increases with carry trades from zero interest rates into commodity futures and declines during risk aversion from late 2008 into beginning of 2008 originating in doubts about soundness of US bank balance sheets. More careful measurement should show that the terms of trade of Japan, export prices relative to import prices, declined during the commodity shocks originating in unconventional monetary policy. The decline of the terms of trade restricted potential growth of income in Japan. The import corporate goods price index on the yen basis increased from 93.5 in Jun 2009 to 113.1 in Apr 2012 or 21.0 percent and to 128.8 in Dec 2013 or gain of 13.9 percent relative to Apr 2012 and 37.8 percent relative to Jun 2009.

Chart IV-8, Japan, Import Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Yen Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Chart IV-8A provides the import corporate goods price index on the contract currency basis. The import corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased from 86.2 in Jun 2009 to 119.5 in Apr 2012 or 38.6 percent and to 113.6 in Dec 2013 or minus 4.9 percent relative to Apr 2012 and gain of 31.8 percent relative to Jun 2009. There is evident deterioration of the terms of trade of Japan: the export corporate goods price index on the basis of the contract currency increased 1.0 percent from Jun 2009 to Dec 2013 while the import corporate goods price index increased 31.8 percent. Prices of Japan’s exports of corporate goods, mostly industrial products, increased only 5.3 percent from Jun 2009 to Apr 2012, while imports of corporate goods, mostly commodities and raw materials increased 38.6 percent. Unconventional monetary policy induces carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in commodities that squeeze economic activity of industrial countries by increases in prices of imported commodities and raw materials during periods without risk aversion. Reversals of carry trades during periods of risk aversion decrease prices of exported commodities and raw materials that squeeze economic activity in economies exporting commodities and raw materials. Devaluation of the dollar by unconventional monetary policy could increase US competitiveness in world markets but economic activity is squeezed by increases in prices of imported commodities and raw materials. Unconventional monetary policy causes instability worldwide instead of the mission of central banks of promoting financial and economic stability.

Chart IV-8A, Japan, Import Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, Contract Currency Basis, 2008-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

Table IV-8 provides the Bank of Japan’s Corporate Goods Price indexes of exports and imports on the yen and contract bases from Jan 2008 to Dec 2013. There are oscillations of the indexes that are shown vividly in the four charts above. For the entire period from Jan 2008 to Dec 2013, the export index on the contract currency basis decreased 0.3 percent and decreased 4.6 percent on the yen basis. For the entire period from Jan 2008 to Dec 2013, the import index increased 12.8 percent on the contract currency basis and increased 8.2 percent on the yen basis. The charts show sharp deteriorations in relative prices of exports to prices of imports during multiple periods. Price margins of Japan’s producers are subject to periodic squeezes resulting from carry trades from zero interest rates of monetary policy to exposures in commodities.

Table IV-8, Japan, Exports and Imports Corporate Goods Price Index, Contract Currency Basis and Yen Basis

| Month | Exports Contract | Exports Yen | Imports Contract Currency | Imports Yen |

| 2008/01 | 99.2 | 115.5 | 100.7 | 119.0 |

| 2008/02 | 99.8 | 116.1 | 102.4 | 120.6 |

| 2008/03 | 100.5 | 112.6 | 104.5 | 117.4 |

| 2008/04 | 101.6 | 115.3 | 110.1 | 125.2 |

| 2008/05 | 102.4 | 117.4 | 113.4 | 130.4 |

| 2008/06 | 103.5 | 120.7 | 119.5 | 140.3 |

| 2008/07 | 104.7 | 122.1 | 122.6 | 143.9 |

| 2008/08 | 103.7 | 122.1 | 123.1 | 147.0 |

| 2008/09 | 102.7 | 118.3 | 117.1 | 137.1 |

| 2008/10 | 100.2 | 109.6 | 109.1 | 121.5 |

| 2008/11 | 98.6 | 104.5 | 97.8 | 105.8 |

| 2008/12 | 97.9 | 100.6 | 89.3 | 93.0 |

| 2009/01 | 98.0 | 99.5 | 85.6 | 88.4 |

| 2009/02 | 97.5 | 100.1 | 85.7 | 89.7 |

| 2009/03 | 97.3 | 104.2 | 85.2 | 93.0 |

| 2009/04 | 97.6 | 105.6 | 84.4 | 93.0 |

| 2009/05 | 97.5 | 103.8 | 84.0 | 90.8 |

| 2009/06 | 97.9 | 104.9 | 86.2 | 93.5 |

| 2009/07 | 97.5 | 103.1 | 89.2 | 95.0 |

| 2009/08 | 98.3 | 104.4 | 89.6 | 95.8 |

| 2009/09 | 98.3 | 102.1 | 91.0 | 94.7 |

| 2009/10 | 98.0 | 101.2 | 91.0 | 94.0 |

| 2009/11 | 98.4 | 100.8 | 92.8 | 94.8 |

| 2009/12 | 98.3 | 100.7 | 95.4 | 97.5 |

| 2010/01 | 99.4 | 102.2 | 97.0 | 100.0 |

| 2010/02 | 99.7 | 101.6 | 97.6 | 99.8 |

| 2010/03 | 99.7 | 101.8 | 97.0 | 99.2 |

| 2010/04 | 100.5 | 104.6 | 99.9 | 104.6 |

| 2010/05 | 100.7 | 102.9 | 101.7 | 104.9 |

| 2010/06 | 100.1 | 101.6 | 100.0 | 102.3 |

| 2010/07 | 99.4 | 99.0 | 99.9 | 99.8 |

| 2010/08 | 99.1 | 97.3 | 99.5 | 97.5 |

| 2010/09 | 99.4 | 97.0 | 100.0 | 97.2 |

| 2010/10 | 100.1 | 96.4 | 100.5 | 95.8 |

| 2010/11 | 100.7 | 97.4 | 102.6 | 98.2 |

| 2010/12 | 101.2 | 98.3 | 104.4 | 100.6 |

| 2011/01 | 102.1 | 98.6 | 107.2 | 102.6 |

| 2011/02 | 102.9 | 99.5 | 109.0 | 104.3 |

| 2011/03 | 103.5 | 99.6 | 111.8 | 106.3 |

| 2011/04 | 104.1 | 101.7 | 115.9 | 111.9 |

| 2011/05 | 103.9 | 99.9 | 118.8 | 112.4 |

| 2011/06 | 103.8 | 99.3 | 117.5 | 110.5 |

| 2011/07 | 103.6 | 98.3 | 118.3 | 110.2 |

| 2011/08 | 103.6 | 96.6 | 118.6 | 108.1 |

| 2011/09 | 103.7 | 96.1 | 117.0 | 106.2 |

| 2011/10 | 103.0 | 95.2 | 116.6 | 105.6 |

| 2011/11 | 101.9 | 94.8 | 115.4 | 105.4 |

| 2011/12 | 101.5 | 94.5 | 116.1 | 106.2 |

| 2012/01 | 101.8 | 94.0 | 115.0 | 104.2 |

| 2012/02 | 102.4 | 95.8 | 115.8 | 106.4 |

| 2012/03 | 102.9 | 99.2 | 118.3 | 112.9 |

| 2012/04 | 103.1 | 98.7 | 119.5 | 113.1 |

| 2012/05 | 102.3 | 96.3 | 118.1 | 109.8 |

| 2012/06 | 101.4 | 95.0 | 115.2 | 106.7 |

| 2012/07 | 100.6 | 94.0 | 112.0 | 103.5 |

| 2012/08 | 100.9 | 94.1 | 112.4 | 103.6 |

| 2012/09 | 101.0 | 94.1 | 114.7 | 105.2 |

| 2012/10 | 101.1 | 94.8 | 113.8 | 105.2 |

| 2012/11 | 100.9 | 95.9 | 113.2 | 106.5 |

| 2012/12 | 100.7 | 98.0 | 113.4 | 109.5 |

| 2013/01 | 101.0 | 102.4 | 113.8 | 115.4 |

| 2013/02 | 101.5 | 105.9 | 114.8 | 120.2 |

| 2013/03 | 101.3 | 106.6 | 115.1 | 122.0 |

| 2013/04 | 100.2 | 107.5 | 114.1 | 123.8 |

| 2013/05 | 99.6 | 109.1 | 112.6 | 125.3 |

| 2013/06 | 99.2 | 106.1 | 112.0 | 121.2 |

| 2013/07 | 99.0 | 107.4 | 111.6 | 122.9 |

| 2013/08 | 98.9 | 106.0 | 111.7 | 121.3 |

| 2013/09 | 98.9 | 107.1 | 112.9 | 123.9 |

| 2013/10 | 99.1 | 106.6 | 112.9 | 122.7 |

| 2013/11 | 99.0 | 107.9 | 112.9 | 124.7 |

| 2013-12 | 98.9 | 110.2 | 113.6 | 128.8 |

Source: Bank of Japan http://www.boj.or.jp/en/

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html#

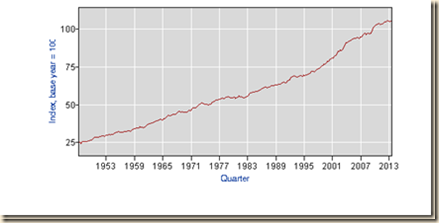

Chart IV-9 provides the monthly corporate goods price index (CGPI) of Japan from 1970 to 2013. Japan also experienced sharp increase in inflation during the 1970s as in the episode of the Great Inflation in the US. Monetary policy focused on accommodating higher inflation, with emphasis solely on the mandate of promoting employment, has been blamed as deliberate or because of model error or imperfect measurement for creating the Great Inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/new-economics-of-rose-garden-turned.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html and Appendix I The Great Inflation; see Taylor 1993, 1997, 1998LB, 1999, 2012FP, 2012Mar27, 2012Mar28, 2012JMCB and http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/rules-versus-discretionary-authorities.html). A remarkable similarity with US experience is the sharp rise of the CGPI of Japan in 2008 driven by carry trades from policy interest rates rapidly falling to zero to exposures in commodity futures during a global recession. Japan had the same sharp waves of consumer price inflation during the 1970s as in the US (see Chart IV-18 and associated table at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/collapse-of-united-states-dynamism-of.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/12/exit-risks-of-zero-interest-rates-world_1.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/twenty-eight-million-unemployed-or_561.html and at http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2013/09/increasing-interest-rate-risk_1.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/recovery-without-jobs-stagnating-real_09.html).

Chart IV-9, Japan, Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index, Monthly, 1970-2013

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.stat-search.boj.or.jp/index_en.html

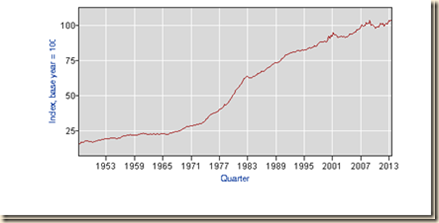

The producer price index of the US from 1970 to 2013 in Chart IV-10 shows various periods of more rapid or less rapid inflation but no bumps. The major event is the decline in 2008 when risk aversion because of the global recession caused the collapse of oil prices from $148/barrel to less than $80/barrel with most other commodity prices also collapsing. The event had nothing in common with explanations of deflation but rather with the concentration of risk exposures in commodities after the decline of stock market indexes. Eventually, there was a flight to government securities because of the fears of insolvency of banks caused by statements supporting proposals for withdrawal of toxic assets from bank balance sheets in the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), as explained by Cochrane and Zingales (2009). The bump in 2008 with decline in 2009 is consistent with the view that zero interest rates with subdued risk aversion induce carry trades into commodity futures.

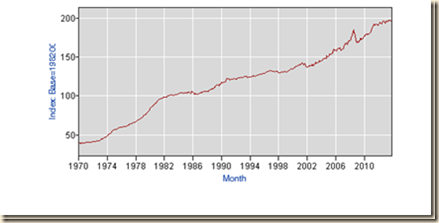

Chart IV-10, US, Producer Price Index Finished Goods, Monthly, 1970-2013

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Further insight into inflation of the corporate goods price index (CGPI) of Japan is provided in Table IV-9. Petroleum and coal with weight of 5.7 percent increased 1.9 percent in Dec 2013 and increased 12.1 percent in 12 months. Japan exports manufactured products and imports raw materials and commodities such that the country’s terms of trade, or export prices relative to import prices, deteriorate during commodity price increases. In contrast, prices of production machinery, with weight of 3.1 percent, decreased 0.8 percent in Dec 2013 and decreased 1.1 percent in 12 months. In general, most manufactured products have been experiencing negative or low increases in prices while inflation rates have been high in 12 months for products originating in raw materials and commodities. Ironically, unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and quantitative easing that intended to increase aggregate demand and GDP growth deteriorated the terms of trade of advanced economies with adverse effects on real income (for analysis of terms of trade and growth see Pelaez (1979, 1976a). There are now inflation effects of the intentional policy of devaluing the yen.

Table IV-9, Japan, Corporate Goods Prices and Selected Components, % Weights, Month and 12 Months ∆%

| Dec 2013 | Weight | Month ∆% | 12 Month ∆% |

| Total | 1000.0 | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| Food, Beverages, Tobacco, Feedstuffs | 137.5 | -0.1 | 0.6 |

| Petroleum & Coal | 57.4 | 1.9 | 12.1 |

| Production Machinery | 30.8 | -0.8 | -1.1 |

| Electronic Components | 31.0 | -0.2 | -2.5 |

| Electric Power, Gas & Water | 52.7 | -0.5 | 10.6 |

| Iron & Steel | 56.6 | 0.5 | 5.2 |

| Chemicals | 92.1 | 0.4 | 3.6 |

| Transport | 136.4 | 0.1 | -0.3 |

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/index.htm/

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1312.pdf

ercentage point contributions to change of the corporate goods price index (CGPI) in Dec 2013 are provided in Table IV-10 divided into domestic, export and import segments. In the domestic CGPI, increasing 0.3 percent in Dec 2013, the energy shock is evident in the contribution of 0.14 percentage points by petroleum and coal products in new carry trades of exposures in commodity futures. The exports CGPI decreased 0.1 percent on the basis of the contract currency with deduction of 0.08 percentage points by metals and related products. The imports CGPI increased 0.6 percent on the contract currency basis. Petroleum, coal and natural gas products contributed 0.55 percentage points. Shocks of risk aversion cause unwinding carry trades that result in declining commodity prices with resulting downward pressure on price indexes. The volatility of inflation adversely affects financial and economic decisions worldwide.

Table IV-10, Japan, Percentage Point Contributions to Change of Corporate Goods Price Index

| Groups Dec 2013 | Contribution to Change Percentage Points |

| A. Domestic Corporate Goods Price Index | Monthly Change: |

| Petroleum & Coal Products | 0.14 |

| Agriculture, Forestry & Fishery Products | 0.05 |

| Nonferrous Metals | 0.04 |

| Chemicals & Related Products | 0.04 |

| Iron & Steel | 0.03 |

| Scrap & Waste | 0.02 |

| Electric Power, Gas & Water | -0.03 |

| B. Export Price Index | Monthly Change: |

| Metals & Related Products | -0.08 |

| Electric & Electronic Products | -0.03 |

| Transportation Equipment | -0.02 |

| Chemicals & Related Products | -0.02 |

| Other Primary Products & Manufactured Goods | 0.07 |

| C. Import Price Index | Monthly Change: 0.6% contract currency basis |

| Petroleum, Coal & Natural Gas | 0.55 |

| Chemicals & Related Products | 0.05 |

| Wood, Lumber & Related Products | 0.02 |

| Metals & Related Products | -0.03 |

Source: Bank of Japan

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/index.htm/

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1312.pdf

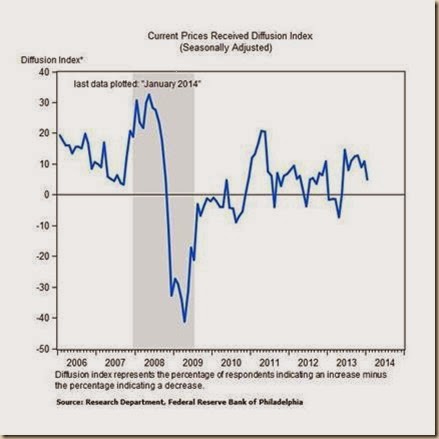

There are two categories of responses in the Empire State Manufacturing Survey of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (http://www.newyorkfed.org/survey/empire/empiresurvey_overview.html): current conditions and expectations for the next six months. There are responses in the survey for two types of prices: prices received or inputs of production and prices paid or sales prices of products. Table IV-5 provides indexes for the two categories and within them for the two types of prices from Jan 2011 to Jan 2014. The index of current prices paid or costs of inputs increased from 16.13 in Dec 2012 to 36.59 in Jan 2014 while the index of current prices received or sales prices increased from 1.08 in Dec 2012 to 13.41 in Jan 2014. The farther the index is from the area of no change at zero, the faster the rate of change. Prices paid or of inputs at 36.59 in Jan 2014 are expanding more rapidly than prices received or of sales of products at 13.41. The index of future prices paid or expectations of costs of inputs in the next six months fell from 51.61 in Dec 2012 to 44.12 in Jan 2014 while the index of future prices received or expectation of sales prices in the next six months decreased from 25.81 in Dec 2012 to 23.17 in Jan 2014. Priced paid or of inputs are expected to increase at a faster pace in the next six months than prices received or prices of sales products. Prices of sales of finished products are less dynamic than prices of costs of inputs during waves of increases. Prices of costs of costs of inputs fall less rapidly than prices of sales of finished products during waves of price decreases. As a result, margins of prices of sales less costs of inputs oscillate with typical deterioration against producers, forcing companies to manage tightly costs and labor inputs. Instability of sales/costs margins discourages investment and hiring.

Table IV-5, US, FRBNY Empire State Manufacturing Survey, Diffusion Indexes, Prices Paid and Prices Received, SA

| Current Prices Paid | Current Prices Received | Six Months Prices Paid | Six Months Prices Received | |

| Jan 2014 | 36.59 | 13.41 | 45.12 | 23.17 |

| Dec 2013 | 15.66 | 3.61 | 48.19 | 27.71 |

| Nov | 17.11 | -3.95 | 42.11 | 17.11 |

| Oct | 21.69 | 2.41 | 45.78 | 25.30 |

| Sep | 21.51 | 8.60 | 39.78 | 24.73 |

| Aug | 20.48 | 3.61 | 40.96 | 19.28 |

| Jul | 17.39 | 1.09 | 28.26 | 11.96 |

| Jun | 20.97 | 11.29 | 45.16 | 17.74 |

| May | 20.45 | 4.55 | 29.55 | 14.77 |

| Apr | 28.41 | 5.68 | 44.32 | 14.77 |

| Mar | 25.81 | 2.15 | 50.54 | 23.66 |

| Feb | 26.26 | 8.08 | 44.44 | 13.13 |

| Jan | 22.58 | 10.75 | 38.71 | 21.51 |

| Dec 2012 | 16.13 | 1.08 | 51.61 | 25.81 |

| Nov | 14.61 | 5.62 | 39.33 | 15.73 |

| Oct | 17.20 | 4.30 | 44.09 | 24.73 |

| Sep | 19.15 | 5.32 | 40.43 | 23.40 |

| Aug | 16.47 | 2.35 | 31.76 | 14.12 |

| Jul | 7.41 | 3.70 | 35.80 | 16.05 |

| Jun | 19.59 | 1.03 | 34.02 | 17.53 |

| May | 37.35 | 12.05 | 57.83 | 22.89 |

| Apr | 45.78 | 19.28 | 50.60 | 22.89 |

| Mar | 50.62 | 13.58 | 66.67 | 32.10 |

| Feb | 25.88 | 15.29 | 62.35 | 34.12 |

| Jan | 26.37 | 23.08 | 53.85 | 30.77 |

| Dec 2011 | 24.42 | 3.49 | 56.98 | 36.05 |

| Nov | 18.29 | 6.10 | 36.59 | 25.61 |

| Oct | 22.47 | 4.49 | 40.45 | 17.98 |

| Sep | 32.61 | 8.70 | 53.26 | 22.83 |

| Aug | 28.26 | 2.17 | 42.39 | 15.22 |

| Jul | 43.33 | 5.56 | 51.11 | 30.00 |

| Jun | 56.12 | 11.22 | 55.10 | 19.39 |

| May | 69.89 | 27.96 | 68.82 | 35.48 |

| Apr | 57.69 | 26.92 | 56.41 | 38.46 |

| Mar | 53.25 | 20.78 | 71.43 | 36.36 |

| Feb | 45.78 | 16.87 | 55.42 | 27.71 |

| Jan | 35.79 | 15.79 | 60.00 | 42.11 |

Source: http://www.newyorkfed.org/survey/empire/empiresurvey_overview.html