Recovery without Hiring, Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs, Record High Youth and Middle-Aged Unemployment, Financial Turbulence and World Economic Slowdown with Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011, 2012

Executive Summary

I Recovery without Hiring

IA Hiring Collapse

IB Labor Underutilization

IC Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

ID Youth and Middle-Aged Unemployment

II United States International Trade

IIA United States International Trade Balance

IIB United States Import and Export Prices

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendix I The Great Inflation

Executive Summary

ESI Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels have increased by only 4 percent since Jan 2009. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job currently is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer forthcoming in the American Economic Review on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar amount of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/08/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html ). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled.

An important characteristic of the current fractured labor market of the US is the closing of the avenue for exiting unemployment and underemployment normally available through dynamic hiring. Another avenue that is closed is the opportunity for advancement in moving to new jobs that pay better salaries and benefits again because of the collapse of hiring in the United States. Those who are unemployed or underemployed cannot find a new job even accepting lower wages and no benefits. The employed cannot escape declining inflation-adjusted earnings because there is no hiring. The objective of this section is to analyze hiring and labor underutilization in the United States.

An appropriate measure of job stress is considered by Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53):

“The right measure of the state of the labor market is the exit rate from unemployment, defined as the number of hires divided by the number unemployed, rather than the unemployment rate itself. What matters to the unemployed is not how many of them there are, but how many of them there are in relation to the number of hires by firms.”

The natural rate of unemployment and the similar NAIRU are quite difficult to estimate in practice (Ibid; see Ball and Mankiw 2002).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) created the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) with the purpose that (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/jltover.htm#purpose):

“These data serve as demand-side indicators of labor shortages at the national level. Prior to JOLTS, there was no economic indicator of the unmet demand for labor with which to assess the presence or extent of labor shortages in the United States. The availability of unfilled jobs—the jobs opening rate—is an important measure of tightness of job markets, parallel to existing measures of unemployment.”

The BLS collects data from about 16,000 US business establishments in nonagricultural industries through the 50 states and DC. The data are released monthly and constitute an important complement to other data provided by the BLS (see also Lazear and Spletzer 2012Mar, 6-7).

Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 69.4 million in 2004 to 50.1 million in 2011 or by 19.3 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 59.5 million in 2006 to 46.9 million in 2011 or by 12.6 million, as shown in Table ESI-1. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to employment (RNF) has fallen from 47.2 in 2005 to 38.1 in 2011 and in the private sector (RHP) from 52.1 in 2006 to 42.9 in 2011. The collapse of hiring in the US has not been followed by dynamic labor markets because of the low rate of economic growth of 2.2 percent in the first twelve quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2012 compared with 6.2 percent in prior cyclical expansions (see table I-5 in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/decelerating-united-states-recovery.html).

Table ESI-1, US, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US and Percentage of Total Employment

Percentage of Total Employment

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 | 62,948 | 47.8 | 58,825 | 53.1 |

| 2002 | 58,583 | 44.9 | 54,759 | 50.3 |

| 2003 | 56,451 | 43.4 | 53,056 | 48.9 |

| 2004 | 69,367 | 45.9 | 56,617 | 51.6 |

| 2005 | 63,150 | 47.2 | 59,372 | 53.1 |

| 2006 | 63,773 | 46.9 | 59,494 | 52.1 |

| 2007 | 62,421 | 45.4 | 58,035 | 50.3 |

| 2008 | 55,166 | 40.3 | 51,606 | 45.2 |

| 2009 | 46,398 | 35.5 | 43,052 | 39.8 |

| 2010 | 48,647 | 37.5 | 44,826 | 41.7 |

| 2011 | 50,083 | 38.1 | 46,869 | 42.9 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

Total nonfarm hiring (HNF), total private hiring (HP) and their respective rates are provided for the month of Jun in the years from 2001 to 2012 in Table ESI-2. Hiring numbers are in thousands. There is some recovery in HNF from 4278 thousand (or 4.2 million) in Jun 2009 to 4869 thousand in Jun 2011 and 5057 thousand in Jun 2012 for cumulative gain of 18.2 percent. HP rose from 3925 thousand in Jun 2009 to 4513 thousand in Jun 2011 and 4663 thousand in Jun 2012 for cumulative gain of 18.8 percent. HNF has fallen from 6139 in Jun 2006 to 5057 in Jun 2012 or by 17.6 percent. HP has fallen from 5661 in Jun 2006 to 4663 in Jun 2012 or by 17.6 percent. The labor market continues to be fractured, failing to provide an opportunity to exit from unemployment/underemployment or to find an opportunity for advancement away from declining inflation-adjusted earnings.

Table ESI-2, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in Thousands and in Percentage of Total Employment Not Seasonally Adjusted

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 Jun | 5819 | 4.4 | 5531 | 4.8 |

| 2002 Jun | 5471 | 4.2 | 5054 | 4.6 |

| 2003 Jun | 5369 | 4.1 | 4975 | 4.6 |

| 2004 Jun | 5703 | 4.3 | 5309 | 4.8 |

| 2005 Jun | 6069 | 4.5 | 5675 | 5.0 |

| 2006 Jun | 6139 | 4.5 | 5661 | 4.9 |

| 2007 Jun | 6033 | 4.3 | 5535 | 4.7 |

| 2008 Jun | 5501 | 4.0 | 5087 | 4.4 |

| 2009 Jun | 4278 | 3.3 | 3925 | 3.6 |

| 2010 Jun | 4717 | 3.6 | 4341 | 4.0 |

| 2011 Jun | 4869 | 3.7 | 4513 | 4.1 |

| 2012 Jun | 5057 | 3.8 | 4663 | 4.2 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

Chart ESI-1 provides total nonfarm hiring on a monthly basis from 2001 to 2012. Nonfarm hiring rebounded in early 2010 but then fell and stabilized at a lower level than the early peak not-seasonally adjusted (NSA) of 4786 in May 2010. Nonfarm hiring fell again in Dec 2011 to 3038 from 3844 in Nov and to revised 3633 in Feb 2012, increasing to 4127 in Mar 2012, 4490 in Apr 2012, 4926 in May 2012 and 5057 in Jun 2012. Chart ESI-1 provides seasonally-adjusted (SA) monthly data. The number of seasonally-adjusted hires in Aug 2011 was 4221 thousand, increasing to revised 4444 thousand in Feb 2012, or 5.3 percent, but falling to revised 4335 thousand in Mar 2012 and 4213 in Apr 2012, or cumulative decline of 0.2 percent relative to Aug 2011, increasing to 4361 in Jun 2012 for cumulative increase of 2.0 percent from 4276 in Sep 2012. The number of hires not seasonally adjusted was 4655 in Aug 2011, falling to 3038 in Dec but increasing to 4072 in Jan 2012, increasing to 5057 in May 2012. The number of nonfarm hiring not seasonally adjusted fell by 34.7 percent from 4655 in Aug 2011 to 3038 in Dec 2011 in a yearly-repeated seasonal pattern.

Chart ESI-1, US, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF), 2001-2012 Month SA

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

Similar behavior occurs in the rate of nonfarm hiring plot in Chart ESI-2 Recovery in early 2010 was followed by decline and stabilization at a lower level but with stability in monthly SA estimates of 3.2 in Sep 2011 to 3.2 in Jan 2012, increasing to 3.4 in May 2012 and 3.3 in Jun 2012. The rate not seasonally adjusted fell from 3.7 in Jun 2011 to 2.3 in Dec, climbing to 3.1 in Jan 2012 and 3.8 in Jun 2012. Rates of nonfarm hiring NSA were in the range of 2.8 (Dec) to 4.5 (Jun) in 2006.

Chart ESI-2, US, Rate Total Nonfarm Hiring, Month SA 2001-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

There is only milder improvement in total private hiring shown in Chart ESI-3. Hiring private (HP) rose in 2010 followed by stability and renewed increase in 2011. The number of private hiring seasonally adjusted fell from 4002 thousand in Sep 2011 to 3889 in Dec or by 2.8 percent, increasing to 3945 in Jan 2012 or decline by 1.4 relative to the level in Sep 2011 but increasing to 4080 in Jun 2012 or by 1.9 percent relative to Sep 2011. The number of private hiring not seasonally adjusted fell from 4130 in Sep 2011 to 2856 in Dec or by 30.8 percent, reaching 3782 in Jan 2012 or decline of 8.4 percent relative to Sep 2011 but increasing to 4663 in Jun 2012 or 12.9 percent relative to Sep 2011. Companies do not hire in the latter part of the year that explains the high seasonality in year-end employment data. For example, NSA private hiring fell from 4934 in Sep 2006 to 3635 in Dec 2006 or by 26.3 percent. Private hiring NSA data are useful in showing the huge declines from the period before the global recession. In Jul 2006 private hiring NSA was 5555, declining to 4293 in Jul 2011 or by 22.7 percent. The conclusion is that private hiring in the US is more than 20 percent below the hiring before the global recession. The main problem in recovery of the US labor market has been the low rate of growth of 2.2 percent in the eleven quarters of expansion of the economy from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2012 compared with average 6.2 percent in prior expansions from contractions (see table I-5 in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/decelerating-united-states-recovery.html). The US missed the opportunity to recover employment as in past cyclical expansions from contractions.

Chart ESII-3, US, Total Private Hiring Month SA 2011-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

Chart ESIV-4 shows similar behavior in the rate of private hiring. The rate in 2011 in monthly SA data has not risen significantly above the peak in 2010. The rate seasonally adjusted fell from 3.6 in Sep 2011 to 3.5 in Dec 2011, increasing to 3.6 in Jan 2012 and 3.7 in Jun 2012. The rate not seasonally adjusted (NSA) fell from 3.8 in Sep 2011 to 2.6 in Dec 2011, increasing to revised 3.5 in Jan 2012 and 4.2 in Jun 2012. The NSA rate of private hiring fell from 4.9 in Jun 2006 to 3.6 in Jun 2009 but recovery was insufficient to only 4.1 in Jun 2011.

Chart ESI-4, US, Rate Total Private Hiring Month SA 2011-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

ESII Ten Million Fewer Full-Time Jobs. There is strong seasonality in US labor markets around the end of the year. The number employed part-time for economic reasons because they could not find full-time employment fell from 9.270 million in Sep 2011 to 8.246 million in Jun 2010, seasonally adjusted, or decline of 1.024 million in nine months, as shown in Table ESII-1. The number employed full-time increased from 112.479 million in Sep 2011 to 115.290 million in Mar 2012 or 2.811 million but then fell to 114.212 million in May 2012 or 1.078 million fewer full-time employed than in Mar 2012. There is a jump in the level of full-time SA to 114.573 million in Jun 2012 or 361,000 relative to May 2012 but then decline to 114.345 million in Jul 2012 or decline of 228,000 full time jobs from Jun 2012 into Jul 2012. The number of employed part-time for economic reasons actually increased without seasonal adjustment from 8.271 million in Nov 2011 to 8.428 million in Dec 2011 or by 157,000 and then to 8.918 million in Jan 2012 or by an additional 490,000 for cumulative increase from Nov 2011 to Jan 2012 of 647,000. The level of employed part-time for economic reasons then fell from 8.918 million in Jan 2012 to 7.867 million in Mar 2012 or by 1.0151 million and to 7.694 million in Apr 2012 or 1.224 million fewer relative to Jan 2012. In Jul, the number employed part-time for economic reasons reached 8.316 million SA or 622,000 more than in Apr 2012. The number employed full time without seasonal adjustment fell from 113.138 million in Nov 2011 to 113.050 million in Dec 2011 or by 88,000 and fell further to 111.879 in Jan 2012 for cumulative decrease of 1.259 million. The number employed full-time not seasonally adjusted fell from 113.138 million in Nov 2011 to 112.587 million in Feb 2012 or by 551.000 but increased to 116.024 million in Jun 2012 or 2.886 million more full-time jobs than in Nov 2011. Comparisons over long periods require use of NSA data. The number with full-time jobs fell from a high of 123.219 million in Jul 2007 to 108.770 million in Jan 2010 or by 14.442 million. The number with full-time jobs in Jul 2012 is 116.131 million, which is lower by 7.1 million relative to the peak of 123.219 million in Jul 2007. There appear to be around 10 million fewer full-time jobs in the US than before the global recession. Growth at 2.2 percent on average in the eleven quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2012 compared with 6.2 percent on average in expansions from postwar cyclical contractions is the main culprit of the fractured US labor market (see table I-5 in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/decelerating-united-states-recovery.html).

Table ESII-1, US, Employed Part-time for Economic Reasons, Thousands, and Full-time, Millions

| Part-time Thousands | Full-time Millions | |

| Seasonally Adjusted | ||

| Jul 2012 | 8,246 | 114.345 |

| Jun 2012 | 8,210 | 114.573 |

| May 2012 | 8,098 | 114.212 |

| Apr 2012 | 7,853 | 114.478 |

| Mar 2012 | 7,672 | 115.290 |

| Feb 2012 | 8,119 | 114.408 |

| Jan 2012 | 8,230 | 113.845 |

| Dec 2011 | 8,098 | 113.765 |

| Nov 2011 | 8,469 | 113.212 |

| Oct 2011 | 8,790 | 112.841 |

| Sep 2011 | 9,270 | 112.479 |

| Aug 2011 | 8,787 | 112.406 |

| Jul 2011 | 8,437 | 112.006 |

| Not Seasonally Adjusted | ||

| Jul 2012 | 8,316 | 116.131 |

| Jun 2012 | 8,394 | 116.024 |

| May 2012 | 7,837 | 114.634 |

| Apr 2012 | 7,694 | 113.999 |

| Mar 2012 | 7,867 | 113.916 |

| Feb 2012 | 8,455 | 112.587 |

| Jan 2012 | 8,918 | 111.879 |

| Dec 2011 | 8,428 | 113.050 |

| Nov 2011 | 8,271 | 113.138 |

| Oct 2011 | 8,258 | 113.456 |

| Jul 2011 | 8,514 | 113.759 |

| Jun 2011 | 8,738 | 113.255 |

| May 2011 | 8,270 | 112.618 |

| Apr 2011 | 8,425 | 111.844 |

| Mar 2011 | 8,737 | 111.186 |

| Feb 2011 | 8,749 | 110.731 |

| Jan 2011 | 9,187 | 110.373 |

| Dec 2010 | 9,205 | 111.207 |

| Nov 2010 | 8,670 | 111.348 |

| Oct 2010 | 8,408 | 112.342 |

| Jul 2010 | 8,737 | 113.974 |

| Jun 2010 | 8,867 | 113.856 |

| May 2010 | 8,513 | 112.809 |

| Apr 2010 | 8,921 | 111.391 |

| Mar 2010 | 9,343 | 109.877 |

| Feb 2010 | 9,282 | 109.100 |

| Jan 2010 | 9,290 | 108.777 (low) |

| Dec 2009 | 9,354 (high) | 109.875 |

| Jul 2009 | 9,103 | 114.184 |

| Jun 2009 | 9,301 | 114.014 |

| May 2009 | 8,785 | 113.083 |

| Apr 2009 | 8,648 | 112.746 |

| Mar 2009 | 9,305 | 112.215 |

| Feb 2009 | 9,170 | 112.947 |

| Jan 2009 | 8,829 | 113.815 |

| Jul 2008 | 6,054 | 122.378 |

| Jun 2008 | 5,697 | 121.845 |

| May 2008 | 5,096 | 120.809 |

| Apr 2008 | 5,071 | 120.027 |

| Mar 2008 | 5,038 | 119.875 |

| Feb 2008 | 5,114 | 119.452 |

| Jan 2008 | 5,340 | 119.322 |

| Jul 2007 | 4,516 | 123.219 (high) |

| Jun 2007 | 4,469 | 122.150 |

| May 2007 | 4,315 | 120.846 |

| Apr 2007 | 4,205 | 119.609 |

| Mar 2007 | 4,384 | 119.640 |

| Feb 2007 | 4,417 | 119.041 |

| Jan 2007 | 4,726 | 119.094 |

| Sep 2006 | 3,735 (low) | 120.780 |

| Jul 2006 | 4,450 | 121.951 |

| Jun 2006 | 4,456 | 121.070 |

| May 2006 | 3,968 | 118.925 |

| Apr 2006 | 3,787 | 118.559 |

| Mar 2006 | 4,097 | 117.693 |

| Feb 2006 | 4,403 | 116.823 |

| Jan 2006 | 4,597 | 116.395 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm

People lose their marketable job skills after prolonged unemployment and find increasing difficulty in finding another job. Chart ESII-1 shows the sharp rise in unemployed over 27 weeks and stabilization at an extremely high level.

Chart ESII-1, US, Number Unemployed for 27 Weeks or Over, Thousands SA Month 2001-2011

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm

Another segment of U6 consists of people marginally attached to the labor force who continue to seek employment but less frequently on the frustration there may not be a job for them. Chart ESII-2 shows the sharp rise in people marginally attached to the labor force after 2007 and subsequent stabilization.

Chart ESII-2, US, Marginally Attached to the Labor Force, NSA Month 2001-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm

Chart ESII-3 reveals the fracture in the US labor market. The number of workers with full-time jobs not-seasonally-adjusted rose with fluctuations from 2002 to a peak in 2007, collapsing during the global recession. The terrible state of the job market is shown in the segment from 2009 to 2012 with fluctuations around the typical behavior of a stationary series: there is no improvement in the United States in creating full-time jobs.

Chart ESII-3, US, Full-time Employed, Thousands, NSA, 2001-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm

ESIII Youth and Middle-Aged Unemployment. The United States is experiencing high youth unemployment as in European economies. Table ESIII-1 provides the employment level for ages 16 to 24 years of age estimated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. On an annual basis, youth employment fell from 20.041 million in 2006 to 17.362 million in 2011 or 2.679 million fewer youth jobs. During the seasonal peak months of youth employment in the summer from Jun to Aug, youth employment has fallen by more than two million jobs. There are two hardships behind these data. First, young people cannot find employment after finishing high-school and college, reducing prospects for achievement in older age. Second, students with more modest means cannot find employment to keep them in college.

Table ESIII-1, US, Employment Level 16-24 Years, Thousands, NSA

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Annual |

| 2001 | 19778 | 19648 | 21212 | 22042 | 20088 |

| 2002 | 19108 | 19484 | 20828 | 21501 | 19683 |

| 2003 | 18873 | 19032 | 20432 | 20950 | 19351 |

| 2004 | 19184 | 19237 | 20587 | 21447 | 19630 |

| 2005 | 19071 | 19356 | 20949 | 21749 | 19770 |

| 2006 | 19406 | 19769 | 21268 | 21914 | 20041 |

| 2007 | 19368 | 19457 | 21098 | 21717 | 19875 |

| 2008 | 19161 | 19254 | 20466 | 21021 | 19202 |

| 2009 | 17739 | 17588 | 18726 | 19304 | 17601 |

| 2010 | 16764 | 17039 | 17920 | 18564 | 17077 |

| 2011 | 16970 | 17045 | 18180 | 18632 | 17362 |

| 2012 | 17387 | 17681 | 18907 | 19461 |

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart ESIII-1 provides US employment level ages 16 to 24 years from 2002 to 2012. Employment level is sharply lower in Jun 2012 relative to the peak in 2007.

Chart ESIII-1, US, Employment Level 16-24 Years, Thousands SA, 2001-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table ESIII-2 provides US unemployment level ages 16 to 24 years. The number unemployed ages 16 to 24 years increased from 2342 thousand in 2007 to 3634 thousand in 2011 or by 1.292 million. This situation may persist for many years.

Table ESIII-2, US, Unemployment Level 16-24 Years, Thousands NSA

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Annual |

| 2001 | 2095 | 2171 | 2775 | 2585 | 2461 | 2371 |

| 2002 | 2515 | 2568 | 3167 | 3034 | 2688 | 2683 |

| 2003 | 2572 | 2838 | 3542 | 3200 | 2724 | 2746 |

| 2004 | 2387 | 2684 | 3191 | 3018 | 2585 | 2638 |

| 2005 | 2398 | 2619 | 3010 | 2688 | 2519 | 2521 |

| 2006 | 2092 | 2254 | 2860 | 2750 | 2467 | 2353 |

| 2007 | 2074 | 2203 | 2883 | 2622 | 2388 | 2342 |

| 2008 | 2196 | 2952 | 3450 | 3408 | 2990 | 2830 |

| 2009 | 3321 | 3851 | 4653 | 4387 | 4004 | 3760 |

| 2010 | 3803 | 3854 | 4481 | 4374 | 3903 | 3857 |

| 2011 | 3365 | 3628 | 4248 | 4110 | 3820 | 3634 |

| 2012 | 3175 | 3438 | 4180 | 4011 |

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/cps/data.htm

Chart ESIII-2 provides the unemployment level ages 16 to 24 from 2002 to 2012. The level rose sharply from 2007 to 2010 with tepid improvement into 2012.

Chart ESIII-2, US, Unemployment Level 16-24 Years, Thousands SA, 2001-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Table ESIII-3 provides the rate of unemployment of young peoples in ages 16 to 24 years. The annual rate jumped from 10.5 percent in 2007 to 18.4 percent in 2010 and 17.3 percent in 2011. During the seasonal peak in Jul 2011 the rate of youth unemployed was 18.1 percent compared with 10.8 percent in Jun 2007.

Table ESIII-3, US, Unemployment Rate 16-24 Years, Thousands, NSA

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Annual |

| 2001 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 10.6 |

| 2002 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 13.2 | 12.4 | 11.5 | 12.0 |

| 2003 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.8 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 12.4 |

| 2004 | 11.1 | 12.2 | 13.4 | 12.3 | 11.1 | 11.8 |

| 2005 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 11.3 |

| 2006 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 11.9 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 10.5 |

| 2007 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 12.0 | 10.8 | 10.5 | 10.5 |

| 2008 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.8 |

| 2009 | 15.8 | 18.0 | 19.9 | 18.5 | 18.0 | 17.6 |

| 2010 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 20.0 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| 2011 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 18.9 | 18.1 | 17.5 | 17.3 |

| 2012 | 15.4 | 16.3 | 18.1 | 17.1 |

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart ESIII-3 provides the BLS estimate of the not-seasonally-adjusted rate of youth unemployment for ages 16 to 24 years from 2002 to 2012. The rate of youth unemployment increased sharply during the global recession of 2008 and 2009 but has failed to drop to earlier lower levels during the eleven quarters of expansion of the economy since IIIQ2009.

Chart ESIII-3, US, Unemployment Rate 16-24 Years, Thousands, NSA, 2001-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart ESIII-4 provides longer perspective with the rate of youth unemployment in ages 16 to 24 years from 1948 to 2012. The rate of youth unemployment rose to 20 percent during the contractions of the early 1980s and also during the contraction of the global recession in 2008 and 2009. The data illustrate again the claim in this blog that the contractions of the early 1980s are the valid framework for comparison with the global recession of 2008 and 2009 instead of misleading comparisons with the 1930s. During the initial phase of recovery, the rate of youth unemployment 16 to 24 years NSA fell from 18.9 percent in Jun 1983 to 14.5 percent in Jun 1984 while the rate of youth unemployment 16 to 24 years was nearly the same during the expansion after IIIQ2009: 19.9 percent in Jun 2009, 20.0 percent in Jun 2010, 18.9 percent in Jun 2011 and 18.1 percent in Jun 2012. The difference originates in the vigorous seasonally-adjusted annual equivalent average rate of GDP growth of 5.7 percent during the recovery from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 compared with 2.2 percent on average during the first eleven quarters of expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2012 (see table I-5 in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/decelerating-united-states-recovery.html). The fractured US labor market denies an early start for young people.

Chart ESIII-4, US, Unemployment Rate 16-24 Years, Percent NSA, 1948-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

It is more difficult to move to other jobs after a certain age because of fewer available opportunities for matured individuals than for new entrants into the labor force. Middle-aged unemployed are less likely to find another job. Table ESIII-4 provides the unemployment level ages 45 years and over. The number unemployed ages 45 years and over rose from 1.985 million in Jul 2006 to 4.821 million in July 2010 or by 142.9 percent. The number of unemployed ages 45 years and over declined to 4.405 million in Jul 2012 that is still higher by 121.9 percent than in Jul 2006.

Table ESIII-4, US, Unemployment Level 45 Years and Over, Thousands NSA

| Year | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Annual |

| 2001 | 1421 | 1259 | 1371 | 1539 | 1640 | 1576 |

| 2002 | 2101 | 1999 | 2190 | 2173 | 2114 | 2114 |

| 2003 | 2287 | 2112 | 2212 | 2281 | 2301 | 2253 |

| 2004 | 2160 | 2025 | 2182 | 2116 | 2082 | 2149 |

| 2005 | 1939 | 1844 | 1868 | 2119 | 1895 | 2009 |

| 2006 | 1843 | 1784 | 1813 | 1985 | 1869 | 1848 |

| 2007 | 1871 | 1803 | 1805 | 2053 | 1956 | 1966 |

| 2008 | 2104 | 2095 | 2211 | 2492 | 2695 | 2540 |

| 2009 | 4172 | 4175 | 4505 | 4757 | 4683 | 4500 |

| 2010 | 4770 | 4565 | 4564 | 4821 | 5128 | 4879 |

| 2011 | 4373 | 4356 | 4559 | 4772 | 4592 | 4537 |

| 2012 | 4037 | 4083 | 4084 | 4405 |

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Chart ESIII-5 provides the level unemployed ages 45 years and over. There was sharp increase during the global recession and inadequate decline. There was an increase during the 2001 recession and then stability. The US is facing another challenge of reemploying middle-aged workers.

Chart ESIII-5, US, Unemployment Level Ages 45 Years and Over, Thousands, NSA, 1976-2012

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

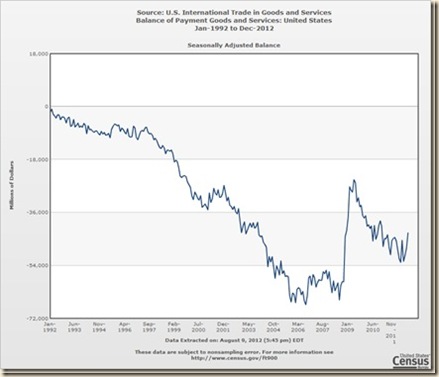

ESIV United States Trade Deficit. Chart ESIV-1 of the US Census Bureau provides the US trade account in goods and services SA from Jan 1992 to Jun 2012. There is a long-term trend of deterioration of the US trade deficit shown vividly by Chart ESIV-1. The trend of deterioration was reversed by the global recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Deterioration resumed together with recovery and was influenced significantly by the carry trade from zero interest rates to commodity futures exposures (these arguments are elaborated in Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 157-66, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 217-27, International Financial Architecture (2005), 15-18, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 221-5, Globalization and the State Vol. II (2008b), 197-213, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 182-4 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/professor-mckinnons-bubble-economy.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/world-inflation-quantitative-easing.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/01/treasury-yields-valuation-of-risk.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/11/quantitative-easing-theory-evidence-and.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html). Earlier research focused on the long-term external imbalance of the US in the form of trade and current account deficits (Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), Globalization and the State Vol. II (2008b) 183-94, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 167-71). US external imbalances have not been resolved and tend to widen together with improving world economic activity and commodity price shocks.

Chart ESIV-1. US, Balance of Trade SA, Monthly Jan 1992-Jun 2012

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/

US exports and imports of goods not seasonally adjusted in Jan-Jun 2012 and Jan-Jun 2011 are shown in Table ESIV-1. The rate of growth of exports was 7.1 percent and 6.0 percent for imports. The US has partial hedge of commodity price increases in exports of agricultural commodities that fell 4.4 percent and of mineral fuels that increased 13.3 percent both because of higher prices of raw materials and commodities that are falling again currently because of shocks of risk aversion. The US exports an insignificant amount of crude oil. US exports and imports consist mostly of manufactured products, with less rapidly increasing prices. US manufactured exports rose 8.2 percent while imports rose 8.1 percent. Significant part of the US trade imbalance originates in imports of mineral fuels declining by 0.9 percent and crude oil increasing 2.6 percent with significant decline at the margin in oil prices. The limited hedge in exports of agricultural commodities and mineral fuels compared with substantial imports of mineral fuels and crude oil results in waves of deterioration of the terms of trade of the US, or export prices relative to import prices, originating in commodity price increases caused by carry trades from zero interest rates. These waves are similar to those in worldwide inflation (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/world-inflation-waves-financial.html).

Table ESIV-1, US, Exports and Imports of Goods, Not Seasonally Adjusted Millions of Dollars and %

| Jan-Jun 2012 $ Millions | Jan-Jun 2011 $ Millions | ∆% | |

| Exports | 773,619 | 722,659 | 7.1 |

| Manufactured | 513,381 | 474,655 | 8.2 |

| Agricultural | 67,241 | 70,357 | -4.4 |

| Mineral Fuels | 67,297 | 59,418 | 13.3 |

| Crude Oil | 813 | 681 | 19.4 |

| Imports | 1,132,171 | 1,068,161 | 6.0 |

| Manufactured | 834,677 | 772,453 | 8.1 |

| Agricultural | 53,121 | 49,944 | 6.4 |

| Mineral Fuels | 223,260 | 225,413 | -0.9 |

| Crude Oil | 167,829 | 163,586 | 2.6 |

Source: US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/

ESV Productivity and Costs. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the Department of Labor provides the quarterly report on productivity and costs. The operational definition of productivity used by the BLS is (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prod2.pdf 1): “Labor productivity, or output per hour, is calculated by dividing an index of real output by an index of hours worked of all persons, including employees, proprietors, and unpaid family workers.” The BLS has revised the estimates for productivity and unit costs. Table ESV-1 provides revised data for nonfarm business sector productivity and unit labor costs for the final quarter of 2011 and the first two quarters of 2012 in seasonally adjusted annual equivalent (SAAE) rate and the percentage change from the same quarter a year earlier. Reflecting increases in output of 2.0 percent and of 0.4 percent in hours worked, nonfarm business sector labor productivity increased at a SAAE rate of 1.6 percent in IIQ2012, as shown in column 2 “IIQ2012 SAEE.” The increase of labor productivity from IIQ2011 to IIQ2012 was 1.1 percent, reflecting increases in output of 2.9 percent and of hours worked of 1.9 percent, as shown in column 3 “IIQ2012 YoY.” Hours worked decreased from 3.2 percent in IQ2011 in SAAE to 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 but output fell from 2.7 percent in IQ2011 to 2.0 percent in IIQ2012 because of the weakening economy. The BLS defines unit labor costs as (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/prod2.pdf 2): “BLS defines unit labor costs as the ratio of hourly compensation to labor productivity; increases in hourly compensation tend to increase unit labor costs and increases in output per hour tend to reduce them.” Unit labor costs increased at the SAAE rate of 1.7 percent in IIQ2012 and rose 0.8 percent in IIQ2012 relative to IIQ2011. Hourly compensation in IIQ2012 increased at the SAAE rate of 3.3 percent, which deflating by the estimated consumer price increase SAAE rate in IIQ2012 results in increase of real hourly compensation by 2.6 percent. Real hourly compensation was flat in IIQ2012 relative to IIQ2011.

Table ESV-1, US, Nonfarm Business Sector Productivity and Costs %

| IIQ | IIQ | IQ 2012 SAAE | IQ 2012 YoY | IVQ 2011 SAAE | IVQ 2011 YoY | |

| Productivity | 1.6 | 1.1 | -0.5 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| Output | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 2.5 |

| Hours | 0.4 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Hourly | 3.3 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 1.0 | -0.7 | 2.0 |

| Real Hourly Comp. | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.6 | -1.7 | -1.9 | -1.3 |

| Unit Labor Costs | 1.7 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 0.0 | -3.3 | 1.4 |

| Unit Nonlabor Payments | 1.4 | 3.1 | -3.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 2.6 |

| Implicit Price Deflator | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

Notes: SAAE: seasonally adjusted annual equivalent; Comp.: compensation; YoY: Quarter on Same Quarter Year Earlier

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

In 2011, productivity increased 0.7 percent in the annual average, as shown in Table ESV-2. Increases in productivity were revised to 3.1 percent in the 2010 annual average and 2.9 percent in the 2009 annual average. The contraction period and the recovery period have been characterized by savings of labor inputs. Real hourly compensation fell 0.5 percent in 2011, interrupting increases of 1.8 percent in 2009 and 0.4 percent in 2010. Unit labor costs fell 1.5 percent in 2009 and 1.0 percent in 2010 but increased 2.0 percent in 2011.

Table ESV-2, US, Revised Nonfarm Business Sector Productivity and Costs Annual Average, ∆% Annual Average

| 2011 ∆% | 2010 ∆% | 2009 ∆% | 2008 ∆% | 2007 ∆% | |

| Productivity | 0.7 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| Real Hourly Compensation | -0.5 | 0.4 | 1.8 | -0.4 | 1.1 |

| Unit Labor Costs | 2.0 | -1.0 | -1.5 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Productivity jumped in the recovery after the recession from Mar IQ2001 to Nov IVQ2001 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). Table ESV-3 provides quarter on quarter and annual percentage changes in nonfarm business output per hour, or productivity, from 1999 to 2012. The annual average jumped from 2.9 percent in 2001 to 4.6 percent in 2002. Nonfarm business productivity increased at the SAAE rate of 8.8 percent in the first quarter after the recession in IQ2002. Productivity increases decline later in the expansion period. Productivity increases were mediocre during the recession from Dec IVQ2007 to Jun IIQ2009 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html) and increased during the first phase of expansion from IIQ2009 to IQ2010, trended lower and collapsed in 2011 and 2012.

Table ESV-3, US, Nonfarm Business Output per Hour, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate, 1999-2012

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 3.3 |

| 2000 | -1.5 | 9.4 | 0.1 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| 2001 | -1.3 | 7.4 | 2.5 | 5.8 | 2.9 |

| 2002 | 8.8 | 0.5 | 3.8 | -0.2 | 4.6 |

| 2003 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 3.7 |

| 2004 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| 2005 | 4.2 | -0.8 | 3.1 | -0.2 | 1.6 |

| 2006 | 2.5 | 0.4 | -2.2 | 2.7 | 0.9 |

| 2007 | -0.2 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| 2008 | -2.6 | 2.4 | -0.8 | -3.4 | 0.6 |

| 2009 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 2.9 |

| 2010 | 2.7 | -0.5 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 3.1 |

| 2011 | -2.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| 2012 | -0.5 | 1.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Chart ESV-1 of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides SAAE rates of nonfarm business productivity from 1999 to 2012. There is a clear pattern in both episodes of economic cycles in 2001 and 2007 of rapid expansion of productivity in the transition from contraction to expansion followed by more subdued productivity expansion. Part of the explanation is the reduction in labor utilization resulting from adjustment of business to the sudden shock of collapse of revenue. Productivity rose briefly in the expansion after 2009 but then collapsed and moved to negative change.

Chart ESV-1, US, Nonfarm Business Output per Hour, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate, 1999-2012

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Percentage changes from prior quarter at SAAE rates and annual average percentage changes of nonfarm business unit labor costs are provided in Table ESV-4. Unit labor costs fell during the contractions with continuing negative percentage changes in the early phases of the recovery. Weak labor markets partly explain the decline in unit labor costs. As the economy moves toward full employment, labor markets tighten with increase in unit labor costs. The expansion beginning in IIIQ2009 has been characterized by high unemployment and underemployment. Table ESV-4 shows continuing subdued increases in unit labor costs in 2011 but with increase of 5.6 percent in IQ2012 and 1.7 percent in IIQ2012.

Table ESV-4, US, Nonfarm Business Unit Labor Costs, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2012

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| 2000 | 17.4 | -7.4 | 8.6 | -1.6 | 3.9 |

| 2001 | 10.9 | -5.8 | -1.1 | -1.7 | 1.5 |

| 2002 | -4.1 | 3.4 | -1.6 | 2.2 | -1.3 |

| 2003 | 2.8 | 1.4 | -3.5 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 2004 | -2.5 | 2.4 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 0.7 |

| 2005 | -1.0 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| 2006 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 6.8 | 2.8 |

| 2007 | 4.0 | -1.8 | -1.9 | 4.3 | 2.4 |

| 2008 | 8.7 | -3.4 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2.8 |

| 2009 | -8.2 | -0.2 | -3.1 | -3.9 | -1.5 |

| 2010 | -1.3 | 3.3 | -1.4 | -1.4 | -1.0 |

| 2011 | 11.3 | -1.3 | -0.6 | -3.3 | 2.0 |

| 2012 | 5.6 | 1.7 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Chart ESV-2 provides percentage changes quarter on quarter at SAAE rates of nonfarm business unit labor costs. With the exception of 3.3 percent in IIQ2010, a jump of 11.3 percent in IQ2011, 5.6 percent in IQ2012 and 1.7 percent in IIQ2012, changes in nonfarm business unit labor costs have been negative.

Chart ESV-2, US, Nonfarm Business Unit Labor Costs, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Table ESV-5 provides percentage change from prior quarter at annual rates for nonfarm business real hourly worker compensation. The expansion after the contraction of 2001 was followed by strong recovery of real hourly compensation. Real hourly compensation increased at the rate of 4.4 percent in IQ2011 but fell at annual rates of 4.4 percent in IIQ2011, 3.1 percent in IIIQ2011 and 1.9 percent in IVQ2011 but increased at 2.6 percent in IQ2012 and also in IIQ2012. In 2011, real hourly compensation fell 0.5 percent.

Table ESV-5, Nonfarm Business Real Hourly Compensation, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 1999-2012

| Year | Qtr1 | Qtr2 | Qtr3 | Qtr4 | Annual |

| 1999 | 5.4 | -2.0 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 2.2 |

| 2000 | 11.4 | -1.8 | 4.7 | -0.4 | 4.0 |

| 2001 | 5.4 | -1.5 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 1.6 |

| 2002 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.0 | -0.6 | 1.5 |

| 2003 | 2.4 | 7.7 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| 2004 | -5.2 | 2.6 | 3.7 | -1.1 | 0.6 |

| 2005 | 1.3 | -0.1 | -0.3 | -1.3 | 0.6 |

| 2006 | 3.1 | -1.8 | -2.6 | 11.6 | 0.5 |

| 2007 | -0.2 | -3.0 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 2008 | 1.4 | -6.1 | -2.8 | 12.2 | -0.4 |

| 2009 | -0.7 | 4.7 | -1.6 | -2.1 | 1.8 |

| 2010 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 0.4 | -2.4 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 4.4 | -4.4 | -3.1 | -1.9 | -0.5 |

| 2012 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

Chart ESV-3 provides percentage change from prior quarter at annual rate of nonfarm business real hourly compensation from 1999 to 2012. There are significant fluctuations in quarterly percentage changes oscillating between positive and negative. There is no clear pattern in the two contractions in the 2000s.

Chart ESV-3, US, Nonfarm Business Real Hourly Compensation, Percent Change from Prior Quarter at Annual Rate 2001-2011

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

http://www.bls.gov/lpc/home.htm

ESVI World Economic Slowdown. Table ESVI-1 provides the latest available estimates of GDP for the regions and countries followed in this blog. Growth is weak throughout most of the world. Japan’s GDP increased 1.2 percent in IQ2012 and 2.8 percent relative to a year earlier but part of the jump could be the low level a year earlier because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011. Japan is experiencing difficulties with the overvalued yen because of worldwide capital flight originating in zero interest rates with risk aversion in an environment of softer growth of world trade. China grew at 1.8 percent in IIQ2012, which annualizes to 7.4 percent. Xinhuanet informs that Premier Wen Jiabao considers the need for macroeconomic stimulus, arguing that “we should continue to implement proactive fiscal policy and a prudent monetary policy, while giving more priority to maintaining growth” (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-05/20/c_131599662.htm). Premier Wen elaborates that “the country should properly handle the relationship between maintaining growth, adjusting economic structures and managing inflationary expectations” (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-05/20/c_131599662.htm). China’s GDP grew 7.6 percent in IIQ2012 relative to IQ2011. Growth rates of GDP of China in a quarter relative to the same quarter a year earlier have been declining from 2011 to 2012. GDP was flat in the euro area in IQ2012 and fell 0.1 percent relative to a year earlier. Germany’s GDP increased 0.5 percent in IQ2012 and 1.7 percent relative to a year earlier. US GDP increased 0.4 percent in IIQ2012 and 2.2 percent relative to a year earlier (Section I Mediocre and Decelerating United States Economic Growth http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/decelerating-united-states-recovery.html) but with substantial underemployment and underemployment (Section I http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/08/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/recovery-without-jobs-stagnating-real.html) and weak hiring (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/recovery-without-hiring-ten-million.html). UK GDP fell 0.7 percent in IIQ2012 and fell 0.8 percent relative to IIQ2011. Italy has experienced decline of GDP in four consecutive quarters from IIIQ2011 to IIQ2012. Italy’s GDP fell 0.7 percent in IIQ2012 and declined 2.5 percent relative to IIQ2011.

Table ESVI-1, Percentage Changes of GDP Quarter on Prior Quarter and on Same Quarter Year Earlier, ∆%

| IQ2012/IVQ2011 | IQ2012/IQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.5 SAAR: 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Japan | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| China | 1.8 | 8.1 |

| Euro Area | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| Germany | 0.5 | 1.7 |

| France | 0.0 | 0.3 |

| Italy | -0.8 | -1.4 |

| United Kingdom | -0.3 | -0.2 |

| IIQ2012/IQ2012 | IIQ2012/IIQ2011 | |

| United States | QOQ: 0.4 SAAR: 1.5 | 2.2 |

| China | 1.8 | 7.6 |

| Italy | -0.7 | -2.5 |

| United Kingdom | -0.7 | -0.8 |

QOQ: Quarter relative to prior quarter; SAAR: seasonally adjusted annual rate

Source: Country Statistical Agencies

http://www.bea.gov/national/index.htm#gdp http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/sokuhou/sokuhou_top.html http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/

The JP Morgan Global All-Industry Output Index of the JP Morgan Manufacturing and Services PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, with high association with world GDP, increased from 50.3 in Jun to 51.7 in Jul, indicating expansion at a moderate rate, which is one of the lowest in the current expansion (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9928). This index has remained above the contraction territory of 50.0 during 35 months. Both global manufacturing and services have slowed down considerably with services increasing marginally because of activity in the US while manufacturing deepened its decline. The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM, fell to 48.4 in Jul from 49.1 in Jun, for the lowest reading in three years in two consecutive months below 50.0 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9899). David Hensley, Director of Global Economics Coordination at JPMorgan, finds that inventory adjustment is the driver of deeper contraction in the beginning of IIIQ2012 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9899). The HSBC Brazil Composite Output Index, compiled by Markit, fell from moderate expansion at 51.5 in Jun to moderate contraction at 48.9 in Jul, in the weakest reading in ten months (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9912). Andre Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil, at HSBC, finds that the decline of the HSBC Brazil Services Business Activity Index from 53.0 in Jun to 48.9 in Jul withdraws important support present in the first half of 2012 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9912). The HSBC Brazil Purchasing Managers’ IndexTM (PMI™) increased slightly to 48.7 in Jul from 48.5 in Jun, indicating modest deterioration of business conditions in Brazilian manufacturing (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9876). Andre Loes, Chief Economist, Brazil at HSBC, finds that moderate improvement in the index suggests that drivers of the drop of activity are moderating (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9876).

ESVII Flight to Government Securities of the United States and Germany. Yields on sovereign debt backed up again with the yield of the ten-year government bond of Spain rising sharply to 7.224 percent on Fri Jul 20 while the yield of the ten-year government bond of Italy increased to 6.158 percent but eased again on Fri Jul 27 on the expectations of massive government support with the yield of the ten-year government bond of Spain falling to 6.731 percent and the yield of the ten-year government bond of Italy dropping to 5.956 percent. The ten-year government bond of Spain was quoted at yield of 6.827 percent on Fri Aug 3 and the ten-year government bond of Italy was quoted at 6.064 percent (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata). The ten-year government bond of Spain was quoted at 6.868 percent on Aug 10 and the ten-year government bond of Italy at 5.894 percent. Risk aversion is captured by flight of investors from risk financial assets to the government securities of the US and Germany. Diminishing aversion is captured by increase of the yield of the two- and ten-year Treasury notes and the two- and ten-year government bonds of Germany. Table ESVII-1 provides yields of US and German governments bonds and the rate of USD/EUR. Yields of US and German government bonds decline during shocks of risk aversion and the dollar strengthens in the form of fewer dollars required to buy one euro. The yield of the US ten-year Treasury note fell from 2.202 percent on Aug 26, 2011 to 1.459 percent on Jul 20, 2012, reminiscent of experience during the Treasury-Fed accord of the 1940s that placed a ceiling on long-term Treasury debt (Hetzel and Leach 2001), while the yield of the ten-year government bond of Germany fell from 2.16 percent to 1.17 percent. Under increasing risk appetite, the yield of the ten-year Treasury rose to 1.544 on Jul 27, 2012 and 1.569 percent on Aug 3, 2012, while the yield of the ten-year Government bond of Germany rose to 1.40 percent on Jul 27 and 1.42 percent on Aug 3. The US dollar strengthened significantly from USD 1.450/EUR on Aug 26, 2011, to USD 1.2158 on Jul 20, 2012, or by 16.2 percent, but depreciated to USD 1.2320/EUR on Jul 27, 2012 and 1.2387 on Aug 3, 2012 in expectation of massive support of highly indebted euro zone members. Doubts returned at the end of the week of Aug 10, 2012 with appreciation to USD 1.2290/EUR and decline of the yields of the two-year government bond of Germany to -0.07 percent and of the ten-year to 1.38 percent. Under zero interest rates for the monetary policy rate of the US, or fed funds rate, carry trades ensure devaluation of the dollar if there is no risk aversion but the dollar appreciates in flight to safe haven during episodes of risk aversion. Unconventional monetary policy induces significant global financial instability, excessive risks and low liquidity. The ten-year Treasury yield is still at a level below consumer price inflation of 1.7 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun (see subsection II United States Inflation http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/07/world-inflation-waves-financial.html) and the expectation of higher inflation if risk aversion diminishes. Treasury securities continue to be safe haven for investors fearing risk but with concentration in shorter maturities such as the two-year Treasury. The lower part of Table ESVII-1 provides the same flight to government securities of the US and Germany and the USD during the financial crisis and global recession and the beginning of the European debt crisis in the spring of 2010 with the USD trading at USD 1.192/EUR on Jun 7, 2010.

Table ESVII-1, Two- and Ten-Year Yields of Government Bonds of the US and Germany and US Dollar/EUR Exchange rate

| US 2Y | US 10Y | DE 2Y | DE 10Y | USD/ EUR | |

| 8/10/12 | 0.267 | 1.658 | -0.07 | 1.38 | 1.2290 |

| 8/3/12 | 0.242 | 1.569 | -0.02 | 1.42 | 1.2387 |

| 7/27/12 | 0.244 | 1.544 | -0.03 | 1.40 | 1.2320 |

| 7/20/12 | 0.207 | 1.459 | -0.07 | 1.17 | 1.2158 |

| 7/13/12 | 0.24 | 1.49 | -0.04 | 1.26 | 1.2248 |

| 7/6/12 | 0.272 | 1.548 | -0.01 | 1.33 | 1.2288 |

| 6/29/12 | 0.305 | 1.648 | 0.12 | 1.58 | 1.2661 |

| 6/22/12 | 0.309 | 1.676 | 0.14 | 1.58 | 1.2570 |

| 6/15/12 | 0.272 | 1.584 | 0.07 | 1.44 | 1.2640 |

| 6/8/12 | 0.268 | 1.635 | 0.04 | 1.33 | 1.2517 |

| 6/1/12 | 0.248 | 1.454 | 0.01 | 1.17 | 1.2435 |

| 5/25/12 | 0.291 | 1.738 | 0.05 | 1.37 | 1.2518 |

| 5/18/12 | 0.292 | 1.714 | 0.05 | 1.43 | 1.2780 |

| 5/11/12 | 0.248 | 1.845 | 0.09 | 1.52 | 1.2917 |

| 5/4/12 | 0.256 | 1.876 | 0.08 | 1.58 | 1.3084 |

| 4/6/12 | 0.31 | 2.058 | 0.14 | 1.74 | 1.3096 |

| 3/30/12 | 0.335 | 2.214 | 0.21 | 1.79 | 1.3340 |

| 3/2/12 | 0.29 | 1.977 | 0.16 | 1.80 | 1.3190 |

| 2/24/12 | 0.307 | 1.977 | 0.24 | 1.88 | 1.3449 |

| 1/6/12 | 0.256 | 1.957 | 0.17 | 1.85 | 1.2720 |

| 12/30/11 | 0.239 | 1.871 | 0.14 | 1.83 | 1.2944 |

| 8/26/11 | 0.20 | 2.202 | 0.65 | 2.16 | 1.450 |

| 8/19/11 | 0.192 | 2.066 | 0.65 | 2.11 | 1.4390 |

| 6/7/10 | 0.74 | 3.17 | 0.49 | 2.56 | 1.192 |

| 3/5/09 | 0.89 | 2.83 | 1.19 | 3.01 | 1.254 |

| 12/17/08 | 0.73 | 2.20 | 1.94 | 3.00 | 1.442 |

| 10/27/08 | 1.57 | 3.79 | 2.61 | 3.76 | 1.246 |

| 7/14/08 | 2.47 | 3.88 | 4.38 | 4.40 | 1.5914 |

| 6/26/03 | 1.41 | 3.55 | NA | 3.62 | 1.1423 |

Note: DE: Germany

Source:

http://www.bloomberg.com/markets/

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm

http://www.ecb.int/stats/money/long/html/index.en.html

Chart ESVII-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the ten-year and two-year Treasury constant maturity yields. The combination of zero fed funds rate and quantitative easing caused sharp decline of the yields from 2008 and 2009. Yield declines have also occurred during periods of financial risk aversion, including the current one of stress of financial markets in Europe.

Chart ESVII-1, US, Ten-Year and Two-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Yields 2001-2012

Note: US Recessions in shaded areas

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/update/

ESVIII Exchange Rate Confrontations. The Dow Jones Newswires informs on Oct 15 that the premier of China Wen Jiabao announced that the Chinese yuan will not be further appreciated to prevent adverse effects on exports (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203914304576632790881396896.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection). Bob Davis and Lingling Wei, writing on “China shifts course, lets Yuan drop,” on Jul 25, 2012, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444840104577548610131107868.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), find that China is depreciating the CNY relative to the USD in an effort to diminish the impact of appreciation of the CNY relative to the EUR. Table ESVIII-1 provides the CNY/USD rate from Oct 28, 2011 to Aug 3, 2012 in selected intervals. The CNY/USD revalued by 0.9 percent from Oct 28, 2012 to Apr 27, 2012. The CNY was virtually unchanged relative to the USD by Aug 10, 2012 to CNY 6.3604/USD from the rate of CNY 6.3588/USD on Oct 28, 2011. Meanwhile, the Senate of the US is proceeding with a bill on China’s trade that could create a confrontation but may not be approved by the entire Congress.

Table ESVIII-1, Renminbi Yuan US Dollar Rate

| CNY/USD | ∆% from 10/28/2011 | |

| 8/10/12 | 6.3604 | 0.0 |

| 8/3/12 | 6.3726 | -0.2 |

| 7/27/12 | 6.3818 | -0.4 |

| 7/20/12 | 6.3750 | -0.3 |

| 7/13/12 | 6.3868 | -0.4 |

| 7/6/12 | 6.3658 | -0.1 |

| 6/29/12 | 6.3552 | 0.1 |

| 6/22/12 | 6.3650 | -0.1 |

| 6/15/12 | 6.3678 | -0.1 |

| 6/8/2012 | 6.3752 | -0.3 |

| 6/1/2012 | 6.3708 | -0.2 |

| 4/27/2012 | 6.3016 | 0.9 |

| 3/23/2012 | 6.3008 | 0.9 |

| 2/3/2012 | 6.3030 | 0.9 |

| 12/30/2011 | 6.2940 | 1.0 |

| 11/25/2011 | 6.3816 | -0.4 |

| 10/28/2011 | 6.3588 | - |

Source:

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/mdc_currencies.html?mod=mdc_topnav_2_3000

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_ch.htm

Chart ESVIII-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides the CNY/USD exchange rate from Aug 3, 2003 to Jul 27, 2012 together with US recession dates in shaded areas. China fixed the CNY/USD date for a long period as shown in the horizontal segment from 2000 to 2005. There was systematic revaluation of 17.6 percent from CNY 8.2765 on Jul 21, 2005 to CNY 6.8211 on Jul 15, 2008. China fixed the CNY/USD rate until Jun 7, 2010, to avoid adverse effects on its economy from the global recession, which is shown as a horizontal segment from 2009 until mid 2010. China then continued the policy of appreciation of the CNY relative to the USD with oscillations until the beginning of 2012 when the rate began to move sideways followed by a final upward slope of devaluation that is measured in Table ESVIII-1 but virtually disappeared in the rate of CNY 6,3604/USD on Aug 20, 2012. Revaluation of the CNY relative to the USD by 23.2 percent by Aug 10, 2012 has not reduced the trade surplus of China but reversal of the policy of revaluation could result in international confrontation. The upward slope in the final segment on the right of Chart ESVIII-1 is measured as virtually stability in Table ESVIII-1.

Chart ESVIII-1, Chinese Yuan (CNY) per US Dollar (US), Aug 12, 2003-Aug 3, 2012

Note: US Recessions in Shaded Areas

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/datadownload/Choose.aspx?rel=H10

ESIX Global Financial and Economic Risk. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides an international safety net for prevention and resolution of international financial crises. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) provides analysis of the economic and financial sectors of countries (see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 101-62, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008), 114-23). Relating economic and financial sectors is a challenging task both for theory and measurement. The IMF provides surveillance of the world economy with its Global Economic Outlook (WEO) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/update/01/index.htm), of the world financial system with its Global Financial Stability Report (GFSR) (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fmu/eng/2012/01/index.htm) and of fiscal affairs with the Fiscal Monitor (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2012/update/01/fmindex.htm). There appears to be a moment of transition in global economic and financial variables that may prove of difficult analysis and measurement. It is useful to consider a summary of global economic and financial risks, which are analyzed in detail in the comments of this blog in Section VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets, Table VI-4.

Economic risks include the following:

1. China’s Economic Growth. China is lowering its growth target to 7.5 percent per year. The growth rate of GDP of China in the second quarter of 2012 of 1.8 percent is equivalent to 7.4 percent per year.

2. United States Economic Growth, Labor Markets and Budget/Debt Quagmire. The US is growing slowly with 28.6 million in job stress, fewer 10 million full-time jobs, high youth unemployment, historically-low hiring and declining real wages.

3. Economic Growth and Labor Markets in Advanced Economies. Advanced economies are growing slowly. There is still high unemployment in advanced economies.

4. World Inflation Waves. Inflation continues in repetitive waves globally (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/destruction-of-three-trillion-dollars.html).

A list of financial uncertainties includes:

1. Euro Area Survival Risk. The resilience of the euro to fiscal and financial doubts on larger member countries is still an unknown risk.

2. Foreign Exchange Wars. Exchange rate struggles continue as zero interest rates in advanced economies induce devaluation of their currencies.

3. Valuation of Risk Financial Assets. Valuations of risk financial assets have reached extremely high levels in markets with lower volumes.

4. Duration Trap of the Zero Bound. The yield of the US 10-year Treasury rose from 2.031 percent on Mar 9, 2012, to 2.294 percent on Mar 16, 2012. Considering a 10-year Treasury with coupon of 2.625 percent and maturity in exactly 10 years, the price would fall from 105.3512 corresponding to yield of 2.031 percent to 102.9428 corresponding to yield of 2.294 percent, for loss in a week of 2.3 percent but far more in a position with leverage of 10:1. Min Zeng, writing on “Treasurys fall, ending brutal quarter,” published on Mar 30, 2012, in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303816504577313400029412564.html?mod=WSJ_hps_sections_markets), informs that Treasury bonds maturing in more than 20 years lost 5.52 percent in the first quarter of 2012.

5. Credibility and Commitment of Central Bank Policy. There is a credibility issue of the commitment of monetary policy (Sargent and Silber 2012Mar20).

6. Carry Trades. Commodity prices driven by zero interest rates have resumed their increasing path with fluctuations caused by intermittent risk aversion.

It is in this context of economic and financial uncertainties that decisions on portfolio choices of risk financial assets must be made. There is a new carry trade that learned from the losses after the crisis of 2007 or learned from the crisis how to avoid losses. The sharp rise in valuations of risk financial assets shown in Table VI-1 in the text after the first policy round of near zero fed funds and quantitative easing by the equivalent of withdrawing supply with the suspension of the 30-year Treasury auction was on a smooth trend with relatively subdued fluctuations. The credit crisis and global recession have been followed by significant fluctuations originating in sovereign risk issues in Europe, doubts of continuing high growth and accelerating inflation in China now complicated by political developments, events such as in the Middle East and Japan and legislative restructuring, regulation, insufficient growth, falling real wages, depressed hiring and high job stress of unemployment and underemployment in the US now with realization of growth standstill. The “trend is your friend” motto of traders has been replaced with a “hit and realize profit” approach of managing positions to realize profits without sitting on positions. There is a trend of valuation of risk financial assets driven by the carry trade from zero interest rates with fluctuations provoked by events of risk aversion or the “sharp shifts in risk appetite” of Blanchard (2012WEOApr, XIII). Table ESIX-1, which is updated for every comment of this blog, shows the deep contraction of valuations of risk financial assets after the Apr 2010 sovereign risk issues in the fourth column “∆% to Trough.” There was sharp recovery after around Jul 2010 in the last column “∆% Trough to 8/10/12,” which has been recently stalling or reversing amidst profound risk aversion. “Let’s twist again” monetary policy during the week of Sep 23 caused deep worldwide risk aversion and selloff of risk financial assets (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/collapse-of-household-income-and-wealth.html). Monetary policy was designed to increase risk appetite but instead suffocated risk exposures. There has been rollercoaster fluctuation in risk aversion and financial risk asset valuations: surge in the week of Dec 2, 2011, mixed performance of markets in the week of Dec 9, renewed risk aversion in the week of Dec 16, end-of-the-year relaxed risk aversion in thin markets in the weeks of Dec 23 and Dec 30, mixed sentiment in the weeks of Jan 6 and Jan 13 2012 and strength in the weeks of Jan 20, Jan 27 and Feb 3 followed by weakness in the week of Feb 10 but strength in the weeks of Feb 17 and 24 followed by uncertainty on financial counterparty risk in the weeks of Mar 2 and Mar 9. All financial values have fluctuated with events such as the surge in the week of Mar 16 on favorable news of Greece’s bailout even with new risk issues arising in the week of Mar 23 but renewed risk appetite in the week of Mar 30 because of the end of the quarter and the increase in the firewall of support of sovereign debts in the euro area. New risks developed in the week of Apr 6 with increase of yields of sovereign bonds of Spain and Italy, doubts on Fed policy and weak employment report. Asia and financial entities are experiencing their own risk environments. Financial markets were under stress in the week of Apr 13 because of the large exposure of Spanish banks to lending by the European Central Bank and the annual equivalent growth rate of China’s GDP of 7.4 percent in IQ2012 [(1.018)4], which was repeated in IIQ2012. There was strength again in the week of Apr 20 because of the enhanced IMF firewall and Spain placement of debt, continuing into the week of Apr 27. Risk aversion returned in the week of May 4 because of the expectation of elections in Europe and the new trend of deterioration of job creation in the US. Europe’s sovereign debt crisis and the fractured US job market continued to influence risk aversion in the week of May 11. Politics in Greece and banking issues in Spain were important factors of sharper risk aversion in the week of May 18. Risk aversion continued during the week of May 25 and exploded in the week of Jun 1. Expectations of stimulus by central banks caused valuation of risk financial assets in the week of Jun 8 and in the week of Jun 15. Expectations of major stimulus were frustrated by minor continuance of maturity extension policy in the week of Jun 22 together with doubts on the silent bank run in highly indebted euro area member countries. There was a major rally of valuations of risk financial assets in the week of Jun 29 with the announcement of new measures on bank resolutions by the European Council. New doubts surfaced in the week of Jul 6, 2012 on the implementation of the bank resolution mechanism and on the outlook for the world economy because of interest rate reductions by the European Central, Bank of England and People’s Bank of China. Risk appetite returned in the week of July 13 in relief that economic data suggests continuing high growth in China but fiscal and banking uncertainties in Spain spread to Italy in the selloff of July 20, 2012. Mario Draghi (2012Jul26), president of the European Central Bank, stated: “But there is another message I want to tell you.

Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.” This statement caused return of risk appetite, driving upward valuations of risk financial assets worldwide. Buiter (2011Oct31) analyzes that the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) would need a “bigger bazooka” to bail out euro members in difficulties that could possibly be provided by the ECB. The dimensions of the problem may require more firepower than a bazooka perhaps that of the largest conventional bomb of all times of 44,000 pounds experimentally detonated only once by the US in 1948 (http://www.airpower.au.af.mil/airchronicles/aureview/1967/mar-apr/coker.html). Risk appetite continued in the week of Aug 3, 2012, in expectation of purchases of sovereign bonds by the ECB. Growth of China’s exports by 1.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Jul 2012 released in the week of Aug 10, 2010, together with doubts on the purchases of bonds by the ECB injected a mild dose of risk aversion. The highest valuations in column “∆% Trough to 8/10/12” are by US equities indexes: DJIA 36.4 percent and S&P 500 37.5 percent, driven by stronger earnings and economy in the US than in other advanced economies but with doubts on the relation of business revenue to the weakening economy and fractured job market. The DJIA reached 13,331.77 in intraday trading on Mar 16, which is the highest level in 52 weeks (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata). The carry trade from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in risk financial assets had proved strongest for commodity exposures but US equities have regained leadership. Before the current round of risk aversion, almost all assets in the column “∆% Trough to 8/10/12” had double digit gains relative to the trough around Jul 2, 2010 but now most valuations of equity indexes show increase of less than 10 percent: China’s Shanghai Composite is 8.9 percent below the trough; Japan’s Nikkei Average is 0.8 percent above the trough; DJ Asia Pacific TSM is 7.0 percent above the trough; Dow Global is 10.4 percent above the trough; STOXX 50 of European equities is 11.5 percent above the trough; and NYSE Financial is 6.6 percent above the trough. DJ UBS Commodities is 15.3 percent above the trough. DAX is 22.5 percent above the trough. Japan’s Nikkei Average is 0.8 percent above the trough on Aug 31, 2010 and 21.9 percent below the peak on Apr 5, 2010. The Nikkei Average closed at 8891.44 on Fri Aug 10, 2012 (http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/public/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_PRO_hps_marketdata), which is 13.3 percent lower than 10,254.43 on Mar 11, 2011, on the date of the Tōhoku or Great East Japan Earthquake/tsunami. Global risk aversion erased the earlier gains of the Nikkei. The dollar depreciated by 3.1 percent relative to the euro and even higher before the new bout of sovereign risk issues in Europe. The column “∆% week to 8/10/12” in Table ESIX-1 shows that there were increases of valuations of risk financial assets in the week of Aug 3, 2012 such as 1.1 percent for DAX, 1.3 percent for STOXX 50 of European equities, 0.8 percent for NYSE Financial, 2.9 percent DJ Asia Pacific TSM, 1.7 percent Shanghai Composite and 2.0 percent for Dow Global. DJ UBS Commodities increased 0.2 percent. No valuation decreased. The DJIA increased 0.9 percent and S&P 500 increased 1.1 percent. The USD appreciated 0.8 percent. There are still high uncertainties on European sovereign risks and banking soundness, US and world growth slowdown and China’s growth tradeoffs. Sovereign problems in the “periphery” of Europe and fears of slower growth in Asia and the US cause risk aversion with trading caution instead of more aggressive risk exposures. There is a fundamental change in Table ESIX-1 from the relatively upward trend with oscillations since the sovereign risk event of Apr-Jul 2010. Performance is best assessed in the column “∆% Peak to 8/10/12” that provides the percentage change from the peak in Apr 2010 before the sovereign risk event to Aug 10, 2012. Most risk financial assets had gained not only relative to the trough as shown in column “∆% Trough to 8/10/12” but also relative to the peak in column “∆% Peak to 8/10/12.” There are now only three equity indexes above the peak in Table ESIX-1: DJIA 17.9 percent, S&P 500 15.5 percent and DAX 9.7 percent. There are several indexes below the peak: NYSE Financial Index (http://www.nyse.com/about/listed/nykid.shtml) by 15.1 percent, Nikkei Average by 21.9 percent, Shanghai Composite by 31.5 percent, DJ Asia Pacific by 6.3 percent, STOXX 50 by 5.5 percent and Dow Global by 9.9 percent. DJ UBS Commodities Index is now 1.3 percent below the peak. The US dollar strengthened 18.8 percent relative to the peak. The factors of risk aversion have adversely affected the performance of risk financial assets. The performance relative to the peak in Apr 2010 is more important than the performance relative to the trough around early Jul 2010 because improvement could signal that conditions have returned to normal levels before European sovereign doubts in Apr 2010. An intriguing issue is the difference in performance of valuations of risk financial assets and economic growth and employment. Paul A. Samuelson (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/1970/samuelson-bio.html) popularized the view of the elusive relation between stock markets and economic activity in an often-quoted phrase “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” In the presence of zero interest rates forever, valuations of risk financial assets are likely to differ from the performance of the overall economy. The interrelations of financial and economic variables prove difficult to analyze and measure.

Table ESIX-1, Stock Indexes, Commodities, Dollar and 10-Year Treasury

| Peak | Trough | ∆% to Trough | ∆% Peak to 8/10/ /12 | ∆% Week 8/10/12 | ∆% Trough to 8/10/ 12 | |

| DJIA | 4/26/ | 7/2/10 | -13.6 | 17.9 | 0.9 | 36.4 |

| S&P 500 | 4/23/ | 7/20/ | -16.0 | 15.5 | 1.1 | 37.5 |

| NYSE Finance | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -20.3 | -15.1 | 0.8 | 6.6 |

| Dow Global | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -18.4 | -9.9 | 2.0 | 10.4 |

| Asia Pacific | 4/15/ | 7/2/10 | -12.5 | -6.3 | 2.9 | 7.0 |

| Japan Nikkei Aver. | 4/05/ | 8/31/ | -22.5 | -21.9 | 3.9 | 0.8 |

| China Shang. | 4/15/ | 7/02 | -24.7 | -31.5 | 1.7 | -8.9 |

| STOXX 50 | 4/15/10 | 7/2/10 | -15.3 | -5.5 | 1.3 | 11.5 |

| DAX | 4/26/ | 5/25/ | -10.5 | 9.7 | 1.1 | 22.5 |

| Dollar | 11/25 2009 | 6/7 | 21.2 | 18.8 | 0.8 | -3.1 |

| DJ UBS Comm. | 1/6/ | 7/2/10 | -14.5 | -1.3 | 0.2 | 15.5 |

| 10-Year T Note | 4/5/ | 4/6/10 | 3.986 | 1.658 |

T: trough; Dollar: positive sign appreciation relative to euro (less dollars paid per euro), negative sign depreciation relative to euro (more dollars paid per euro)

Source: http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

I Recovery without Hiring. Professor Edward P. Lazear (2012Jan19) at Stanford University finds that recovery of hiring in the US to peaks attained in 2007 requires an increase of hiring by 30 percent while hiring levels have increased by only 4 percent since Jan 2009. The high level of unemployment with low level of hiring reduces the statistical probability that the unemployed will find a job. According to Lazear (2012Jan19), the probability of finding a new job currently is about one third of the probability of finding a job in 2007. Improvements in labor markets have not increased the probability of finding a new job. Lazear (2012Jan19) quotes an essay coauthored with James R. Spletzer forthcoming in the American Economic Review on the concept of churn. A dynamic labor market occurs when a similar amount of workers is hired as those who are separated. This replacement of separated workers is called churn, which explains about two-thirds of total hiring. Typically, wage increases received in a new job are higher by 8 percent. Lazear (2012Jan19) argues that churn has declined 35 percent from the level before the recession in IVQ2007. Because of the collapse of churn there are no opportunities in escaping falling real wages by moving to another job. As this blog argues, there are meager chances of escaping unemployment because of the collapse of hiring and those employed cannot escape falling real wages by moving to another job (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/08/twenty-nine-million-unemployed-or.html ). Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar, 1) argue that reductions of churn reduce the operational effectiveness of labor markets. Churn is part of the allocation of resources or in this case labor to occupations of higher marginal returns. The decline in churn can harm static and dynamic economic efficiency. Losses from decline of churn during recessions can affect an economy over the long-term by preventing optimal growth trajectories because resources are not used in the occupations where they provide highest marginal returns. Lazear and Spletzer (2012Mar 7-8) conclude that: “under a number of assumptions, we estimate that the loss in output during the recession [of 2007 to 2009] and its aftermath resulting from reduced churn equaled $208 billion. On an annual basis, this amounts to about .4% of GDP for a period of 3½ years.”

There are two additional facts discussed below: (1) there are about ten million fewer full-time jobs currently than before the recession of 2008 and 2009; and (2) the extremely high and rigid rate of youth unemployment is denying an early start to young people ages 16 to 24 years while unemployment of ages 45 years or over has swelled. There are four subsections. IA Hiring Collapse provides the data and analysis on the weakness of hiring in the United States economy. IB Labor Underutilization provides the measures of labor underutilization of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Statistics on the decline of full-time employment are in IC Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs. ID Youth and Middle-Age Unemployment provides the data on high unemployment of ages 16 to 24 years and of ages 45 years or over.

IA Hiring Collapse. An important characteristic of the current fractured labor market of the US is the closing of the avenue for exiting unemployment and underemployment normally available through dynamic hiring. Another avenue that is closed is the opportunity for advancement in moving to new jobs that pay better salaries and benefits again because of the collapse of hiring in the United States. Those who are unemployed or underemployed cannot find a new job even accepting lower wages and no benefits. The employed cannot escape declining inflation-adjusted earnings because there is no hiring. The objective of this section is to analyze hiring and labor underutilization in the United States.

An appropriate measure of job stress is considered by Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53):