Consumer Prices of the

United States Increased 8.6 percent in 12 Months Ending in May 2022, Which Is

the Highest Since 8.9 percent in Dec 1981, Followed by the Third Highest of 8.4

percent in Jan 1982 and the Second highest of 8.5 percent in Mar 2022, US Consumer

Prices Increased at Annual Equivalent 10.5 Percent in Mar-May 2022 and at 1.0

Percent in May 2022 or 12.7 Percent in Annual Equivalent, Consumer Prices

Excluding Food and Energy Increased at

Annual Equivalent 6.2 Percent in Mar-May 2022 and Increased 0.6 Percent in May

2022 or 7.4 Percent Annual Equivalent, US Current Account Deficit Increased to

4.8 Percent of GDP in IQ2022, Stagflation

Risks, Increasing Risks of Recession, Worldwide Fiscal, Monetary and External

Imbalances, World Cyclical Slow Growth, and Government Intervention in

Globalization

Note: This Blog will post only one indicator of the US

economy while we concentrate efforts in completing a book-length manuscript in

the critically important subject of INFLATION.

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M.

Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020,

2021, 2022.

I United States Inflation

IB Long-term US Inflation

IC Current US Inflation

III World Financial Turbulence

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last

Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

Preamble. United States total public debt outstanding is $30.4

trillion and debt held by the public $23.9 trillion (https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/debt-to-the-penny/debt-to-the-penny). The Net International

Investment Position of the United States, or foreign debt, is $18.1 trillion (https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/intinv421.pdf https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2022/04/us-consumer-price-index-increased-85.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2022/01/increase-in-dec-2021-of-nonfarm-payroll.html). The United States

current account deficit is 4.8 percent of GDP in IQ2022, increasing from 3.7

percent in IVQ2021 (https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/trans122.pdf). The Treasury deficit of

the United States reached $2.8 trillion in fiscal year 2021 (https://fiscal.treasury.gov/reports-statements/mts/). Total assets of

Federal Reserve Banks reached $8.9 trillion on Jun 22, 2022 and securities held

outright reached $8.5 trillion (https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1). US GDP nominal NSA

reached $24.4 trillion in IQ2022 (https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Total Treasury

interest-bearing, marketable debt held by private investors increased from

$3635 billion in 2007 to $16,439 billion in Sep 2021 (Fiscal Year 2021) or

increase by 352.2 percent (https://fiscal.treasury.gov/reports-statements/treasury-bulletin/). John Hilsenrath, writing

on “Economists Seek Recession Cues in the Yield Curve,” published in the Wall

Street Journal on Apr 2, 2022, analyzes the inversion of the Treasury yield

curve with the two-year yield at 2.430 on Apr 1, 2022, above the ten-year yield

at 2.374. Hilsenrath argues that inversion appears to signal recession in market

analysis but not in alternative Fed approach.

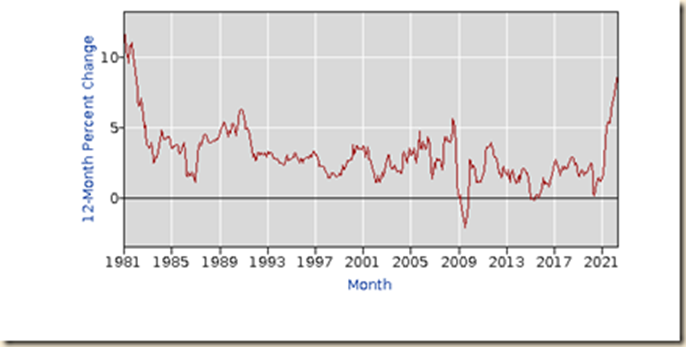

Chart CPI-H provides 12-month percentage changes of the

consumer price index of the United States with 8.6 percent in May 2022, which

is the highest since 8.9 percent in Dec 1981, followed by the second highest of

8.5 percent in Mar 2022 and the third highest of 8.4 percent in Jan 1982.

Chart CPI-H, US, Consumer

Price Index, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1981-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart VII-4 of the Energy Information

Administration provides the price of the Natural Gas Futures Contract

increasing from $2.581 on Jan 4, 2021 to $7.189 per million Btu on Jun 14, 2022

or 178.5 percent. The Natural Gas Continuous Contract NG00 at Nymes settled at

$6.228 on Jun 23, 2022. Several U.S. Energy Information Administration

product releases scheduled for the week of June 20, 2022, will be delayed as

a result of systems issues. (https://www.eia.gov/).

Chart VII-4, US, Natural Gas

Futures Contract 1

Source: US Energy Information

Administration

https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/rngc1d.htm

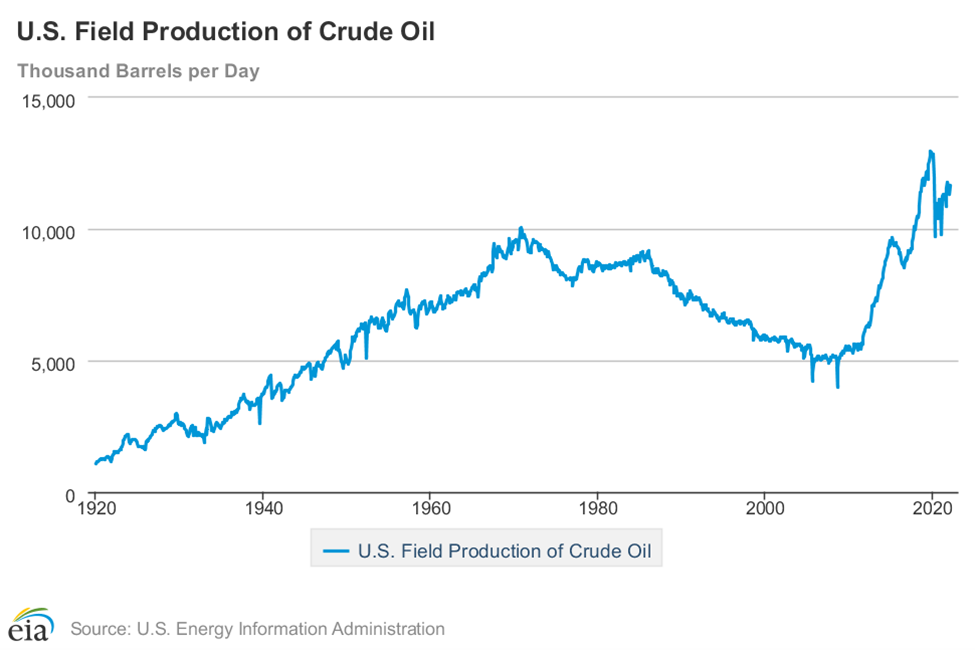

Chart VII-5 of the US Energy Administration provides US field production

of oil decreasing from a peak of 12,966 thousand barrels per day in Nov 2019 to

the final point of 11.655 thousand barrels per day in Mar 2022.

Chart VII-5, US, US, Field Production

of Crude Oil, Thousand Barrels Per Day

Source: US Energy Information

Administration

https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=MCRFPUS2&f=M

Chart VI-6 of the US Energy Information

Administration provides imports of crude oil. Imports increased from 245,369

thousand barrels per day in Jan 2021 to 252,916 thousand in Jan 2022,

increasing to 262.282 in Mar 2022.

Chart VII-6, US, US, Imports

of Crude Oil and Petroleum Products, Thousand Barrels

Source: US Energy Information

Administration

https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=MTTIMUS1&f=M

Chart VI-7 of

the EIA provides US Petroleum Consumption, Production, Imports, Exports and Net

Imports 1950-2020. There was sharp increase in production in the final segment

that reached consumption in 2020.

Chart VI-7, US

Petroleum Consumption, Production, Imports, Exports and Net Imports 1950-2020,

Million Barrels Per Day

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/imports-and-exports.php

Chart VI-8 provides the US

average retail price of electricity at 12.78 cents per kilowatthour in Dec 2020

increasing to 14.47 cents per kilowatthour in Mar 2022 or 13.2 per cent.

Chart VI-8, US

Average Retail Price of Electricity, Monthly, Cents per Kilowatthour,

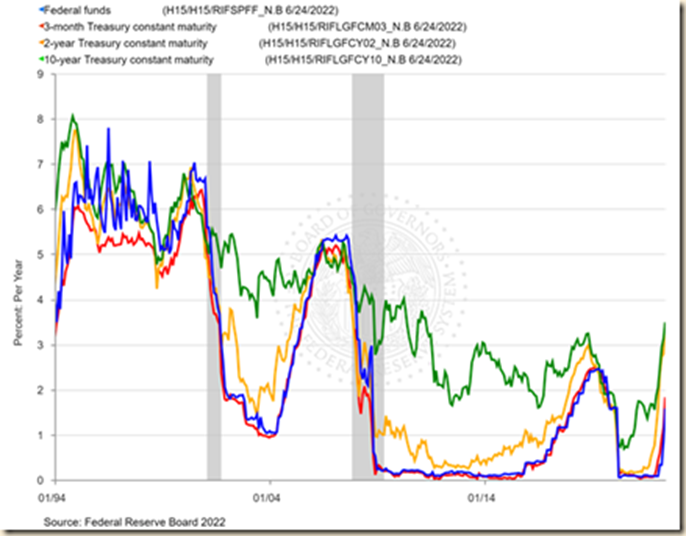

Chart VII-9

provides the fed funds rate and Three Months, Two-Year and Ten-Year Treasury

Constant Maturity Yields. Unconventional monetary policy of near zero interest

rates is typically followed by financial and economic stress with sharp

increases in interest rates.

Chart VII-9, US Fed Funds

Rate and Three-Month, Two-Year and Ten-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Yields,

Jan 2, 1994 to Jun 23, 2022

Source: Federal Reserve Board

of the Federal Reserve System

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

Chart VI-14

provides the overnight fed funds rate, the yield of the 10-year Treasury

constant maturity bond, the yield of the 30-year constant maturity bond and the

conventional mortgage rate from Jan 1991 to Dec 1996. In Jan 1991, the fed

funds rate was 6.91 percent, the 10-year Treasury yield 8.09 percent, the

30-year Treasury yield 8.27 percent and the conventional mortgage rate 9.64

percent. Before monetary policy tightening in Oct 1993, the rates and yields

were 2.99 percent for the fed funds, 5.33 percent for the 10-year Treasury,

5.94 for the 30-year Treasury and 6.83 percent for the conventional mortgage

rate. After tightening in Nov 1994, the rates and yields were 5.29 percent for

the fed funds rate, 7.96 percent for the 10-year Treasury, 8.08 percent for the

30-year Treasury and 9.17 percent for the conventional mortgage rate.

Chart VI-14,

US, Overnight Fed Funds Rate, 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity, 30-Year

Treasury Constant Maturity and Conventional Mortgage Rate, Monthly, Jan 1991 to

Dec 1996

Source: Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/update/

Chart VI-15 of

the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the all items consumer price index from

Jan 1991 to Dec 1996. There does not appear acceleration of consumer prices

requiring aggressive tightening.

Chart VI-15,

US, Consumer Price Index All Items, Jan 1991 to Dec 1996

Source: Bureau

of Labor Statistics

https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart IV-16 of

the Bureau of Labor Statistics provides 12-month percentage changes of the all

items consumer price index from Jan 1991 to Dec 1996. Inflation collapsed

during the recession from Jul 1990 (III) and Mar 1991 (I) and the end of the

Kuwait War on Feb 25, 1991 that stabilized world oil markets. CPI inflation

remained almost the same and there is no valid counterfactual that inflation

would have been higher without monetary policy tightening because of the long lag

in effect of monetary policy on inflation (see Culbertson 1960, 1961, Friedman

1961, Batini and Nelson 2002, Romer and Romer 2004). Policy tightening had

adverse collateral effects in the form of emerging market crises in Mexico and

Argentina and fixed income markets worldwide.

Chart VI-16,

US, Consumer Price Index All Items, Twelve-Month Percentage Change, Jan 1991 to

Dec 1996

Source: Bureau

of Labor Statistics

https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

In his classic

restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference

as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies

the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958,

86):

“The assumption

that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been

adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for

reasons of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in

interest rates and differ from each other in their expectations. For the

purposes of dynamic theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the

theories of sections 2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The

formal apparatus of section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected

capital gain or loss as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest

rate expectations would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the

rate of interest r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In

addition to the rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself,

there would be a further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying

change in the expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates

expectation of capital loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative

quadrant, so that the optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At

the other extreme, expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would

increase sharply the slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no

cash, all consols positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the

investor's expectations, the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to

changes in the rate of interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969)

provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general

equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting

of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital

gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the

expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of

the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus,

g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of

Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of

interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there

is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move

into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk

financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades

with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank

created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global

recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory,

“income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or

believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957,

10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return,

r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Friedman

1957). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that

individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint

for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W.

This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby

1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and

wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r

(1)

Equation (1)

shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W grows without bound, W→∞.

Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest rates to increase the present

value of cash flows derived from projects of firms, creating the impression of

long-term increase in net worth. An attempt to reverse unconventional monetary

policy necessarily causes increases in interest rates, creating the opposite

perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W = Y/r

→0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy without increasing

interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and adverse effects on

production, investment and employment.

Inflation and

unemployment in the period 1966 to 1985 is analyzed by Cochrane (2011Jan, 23)

by means of a Phillips circuit joining points of inflation and unemployment.

Chart VI-1B for Brazil in Pelaez (1986, 94-5) was reprinted in The Economist

in the issue of Jan 17-23, 1987 as updated by the author. Cochrane (2011Jan,

23) argues that the Phillips circuit shows the weakness in Phillips curve

correlation. The explanation is by a shift in aggregate supply, rise in

inflation expectations or loss of anchoring. The case of Brazil in Chart VI-1B

cannot be explained without taking into account the increase in the fed funds

rate that reached 22.36 percent on Jul 22, 1981 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm) in the

Volcker Fed that precipitated the stress on a foreign debt bloated by financing

balance of payments deficits with bank loans in the 1970s. The loans were used

in projects, many of state-owned enterprises with low present value in long

gestation. The combination of the insolvency of the country because of debt

higher than its ability of repayment and the huge government deficit with

declining revenue as the economy contracted caused adverse expectations on

inflation and the economy. This interpretation is consistent with the

case of the 24 emerging market economies analyzed by Reinhart and Rogoff

(2010GTD, 4), concluding that “higher debt levels are associated with

significantly higher levels of inflation in emerging markets. Median inflation

more than doubles (from less than seven percent to 16 percent) as debt rises

frm the low (0 to 30 percent) range to above 90 percent. Fiscal dominance is a

plausible interpretation of this pattern.”

The reading of

the Phillips circuits of the 1970s by Cochrane (2011Jan, 25) is doubtful about

the output gap and inflation expectations:

“So, inflation

is caused by ‘tightness’ and deflation by ‘slack’ in the economy. This is not

just a cause and forecasting variable, it is the cause, because

given ‘slack’ we apparently do not have to worry about inflation from other

sources, notwithstanding the weak correlation of [Phillips circuits]. These

statements [by the Fed] do mention ‘stable inflation expectations. How does the

Fed know expectations are ‘stable’ and would not come unglued once people look

at deficit numbers? As I read Fed statements, almost all confidence in ‘stable’

or ‘anchored’ expectations comes from the fact that we have experienced a long

period of low inflation (adaptive expectations). All these analyses ignore the

stagflation experience in the 1970s, in which inflation was high even with

‘slack’ markets and little ‘demand, and ‘expectations’ moved quickly. They

ignore the experience of hyperinflations and currency collapses, which happen

in economies well below potential.”

Yellen

(2014Aug22) states that “Historically, slack has accounted for only a small

portion of the fluctuations in inflation. Indeed, unusual aspects of the

current recovery may have shifted the lead-lag relationship between a

tightening labor market and rising inflation pressures in either direction.”

Chart VI-1B

provides the tortuous Phillips Circuit of Brazil from 1963 to 1987. There were

no reliable consumer price index and unemployment data in Brazil for that

period. Chart VI-1B used the more reliable indicator of inflation, the

wholesale price index, and idle capacity of manufacturing as a proxy of

unemployment in large urban centers.

Chart VI1-B,

Brazil, Phillips Circuit, 1963-1987

Source: ©Carlos Manuel Pelaez, O Cruzado

e o Austral: Análise das Reformas Monetárias do Brasil e da Argentina.

São

Paulo: Editora Atlas, 1986, pages 94-5. Reprinted in: Brazil. Tomorrow’s Italy,

The Economist, 17-23 January 1987, page 25.

I D Current US

Inflation. Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and

large-scale purchases of long-term securities for the balance sheet of the

central bank is proposed to prevent deflation. The data of CPI inflation of all

goods and CPI inflation excluding food and energy for the past six decades does

not show even one negative change, as shown in Table CPIEX.

Table CPIEX,

Annual Percentage Changes of the CPI All Items Excluding Food and Energy

|

Year |

Annual ∆% |

|

1958 |

2.4 |

|

1959 |

2.0 |

|

1960 |

1.3 |

|

1961 |

1.3 |

|

1962 |

1.3 |

|

1963 |

1.3 |

|

1964 |

1.6 |

|

1965 |

1.2 |

|

1966 |

2.4 |

|

1967 |

3.6 |

|

1968 |

4.6 |

|

1969 |

5.8 |

|

1970 |

6.3 |

|

1971 |

4.7 |

|

1972 |

3.0 |

|

1973 |

3.6 |

|

1974 |

8.3 |

|

1975 |

9.1 |

|

1976 |

6.5 |

|

1977 |

6.3 |

|

1978 |

7.4 |

|

1979 |

9.8 |

|

1980 |

12.4 |

|

1981 |

10.4 |

|

1982 |

7.4 |

|

1983 |

4.0 |

|

1984 |

5.0 |

|

1985 |

4.3 |

|

1986 |

4.0 |

|

1987 |

4.1 |

|

1988 |

4.4 |

|

1989 |

4.5 |

|

1990 |

5.0 |

|

1991 |

4.9 |

|

1992 |

3.7 |

|

1993 |

3.3 |

|

1994 |

2.8 |

|

1995 |

3.0 |

|

1996 |

2.7 |

|

1997 |

2.4 |

|

1998 |

2.3 |

|

1999 |

2.1 |

|

2000 |

2.4 |

|

2001 |

2.6 |

|

2002 |

2.4 |

|

2003 |

1.4 |

|

2004 |

1.8 |

|

2005 |

2.2 |

|

2006 |

2.5 |

|

2007 |

2.3 |

|

2008 |

2.3 |

|

2009 |

1.7 |

|

2010 |

1.0 |

|

2011 |

1.7 |

|

2012 |

2.1 |

|

2013 |

1.8 |

|

2014 |

1.7 |

|

2015 |

1.8 |

|

2016 |

2.2 |

|

2017 |

1.8 |

|

2018 |

2.1 |

|

2019 |

2.2 |

|

2020 |

1.7 |

|

2021 |

3.6 |

Source: US

Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data

Chart I-12 provides the consumer price index NSA from 1913

to 2022. The dominating characteristic is the increase in slope during the

Great Inflation from the middle of the 1960s through the 1970s. There is

long-term inflation in the US and no evidence of deflation risks.

Chart I-12, US, Consumer

Price Index, NSA, 1913-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

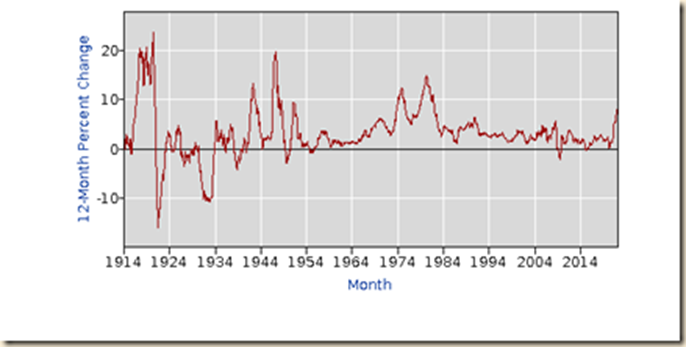

Chart

I-13 provides 12-month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 1914

to 2022. The only episode of deflation after 1950 is in 2009, which is

explained by the reversal of speculative commodity futures carry trades that

were induced by interest rates driven to zero in a shock of monetary policy in

2008. The only persistent case of deflation is from 1930 to 1933, which has

little if any relevance to the contemporary United States economy. There are

actually three waves of inflation in the second half of the 1960s, in the

mid-1970s and again in the late 1970s. Inflation rates then stabilized in a

range with only two episodes above 5 percent.

Chart I-13, US, Consumer

Price Index, All Items, 12- Month Percentage Change 1914-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics

https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Table I-2

provides annual percentage changes of United States consumer price inflation

from 1914 to 2021. There have been only cases of annual declines of the CPI

after wars:

- World War I minus 10.5 percent in 1921 and minus 6.1

percent in 1922 following cumulative increases of 83.5 percent in four

years from 1917 to 1920 at the average of 16.4 percent per year

- World War II: minus 1.2 percent in 1949 following

cumulative 33.9 percent in three years from 1946 to 1948 at average 10.2

percent per year

- Minus 0.4 percent in 1955 two years after the end of

the Korean War

- Minus 0.4 percent in 2009.

- The decline of 0.4 percent in 2009 followed increase of

3.8 percent in 2008 and is explained by the reversal of speculative carry

trades into commodity futures that were created in 2008 as monetary policy

rates were driven to zero. The reversal occurred after misleading

statement on toxic assets in banks in the proposal for TARP (Cochrane and

Zingales 2009).

There were

declines of 1.7 percent in both 1927 and 1928 during the episode of revival of

rules of the gold standard. The only persistent deflationary period since 1914

was during the Great Depression in the years from 1930 to 1933 and again in

1938-1939. Consumer prices increased only 0.1 percent in 2015 because of the

collapse of commodity prices from artificially high levels induced by zero

interest rates. Consumer prices increased 1.3 percent in 2016, increasing at

2.1 percent in 2017. Consumer prices increased 2.4 percent in 2018, increasing

at 1.8 percent in 2019. Consumer prices increased 1.2 percent in 2020. Consumer

prices increased 4.7 percent in 2021 during fiscal, monetary, and external

imbalances. Fear of deflation based on that experience does not justify

unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates that has failed to stop

deflation in Japan. Financial repression causes far more adverse effects on

allocation of resources by distorting the calculus of risk/returns than alleged

employment-creating effects or there would not be current recovery without jobs

and hiring after zero interest rates since Dec 2008 and intended now forever in

a self-imposed forecast growth and employment mandate of monetary policy.

Unconventional monetary policy drives wide swings in allocations of positions

into risk financial assets that generate instability instead of intended

pursuit of prosperity without inflation. There is insufficient knowledge and

imperfect tools to maintain the gap of actual relative to potential output

constantly at zero while restraining inflation in an open interval of (1.99,

2.0). Symmetric targets appear to have been abandoned in favor of a

self-imposed single jobs mandate of easing monetary policy even with the

economy growing at or close to potential output that is actually a target of

growth forecast. The impact on the overall economy and the financial system of

errors of policy are magnified by large-scale policy doses of trillions of

dollars of quantitative easing and zero interest rates. The US economy has been

experiencing financial repression as a result of negative real rates of

interest during nearly a decade and programmed in monetary policy statements

until 2015 or, for practical purposes, forever. The essential calculus of

risk/return in capital budgeting and financial allocations has been distorted.

If economic perspectives are doomed until 2015 such as to warrant zero interest

rates and open-ended bond-buying by “printing” digital bank reserves (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html; see Shultz et

al 2012), rational investors and consumers will not invest and consume until

just before interest rates are likely to increase. Monetary policy statements

on intentions of zero interest rates for another three years or now virtually

forever discourage investment and consumption or aggregate demand that can

increase economic growth and generate more hiring and opportunities to increase

wages and salaries. The doom scenario used to justify monetary policy

accentuates adverse expectations on discounted future cash flows of potential

economic projects that can revive the economy and create jobs. If it were

possible to project the future with the central tendency of the monetary policy

scenario and monetary policy tools do exist to reverse this adversity, why the

tools have not worked before and even prevented the financial crisis? If there

is such thing as “monetary policy science”, why it has such poor record and

current inability to reverse production and employment adversity? There is no

excuse of arguing that additional fiscal measures are needed because they were

deployed simultaneously with similar ineffectiveness. Jon Hilsenrath, writing

on “New view into Fed’s response to crisis,” on Feb 21, 2014, published in the

Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303775504579396803024281322?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection), analyzes

1865 pages of transcripts of eight formal and six emergency policy meetings at

the Fed in 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomchistorical2008.htm). If there

were an infallible science of central banking, models and forecasts would

provide accurate information to policymakers on the future course of the

economy in advance. Such forewarning is essential to central bank science

because of the long lag between the actual impulse of monetary policy and the

actual full effects on income and prices many months and even years ahead

(Romer and Romer 2004, Friedman 1961, 1953, Culbertson 1960, 1961, Batini and

Nelson 2002). Jon Hilsenrath, writing on “New view into Fed’s response to

crisis,” on Feb 21, 2014, published in the Wall Street Journal (http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303775504579396803024281322?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection), analyzed

1865 pages of transcripts of eight formal and six emergency policy meetings at

the Fed in 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomchistorical2008.htm). Jon

Hilsenrath demonstrates that Fed policymakers frequently did not understand the

current state of the US economy in 2008 and much less the direction of income

and prices. The conclusion of Friedman (1953) that monetary impulses increase

financial and economic instability because of lags in anticipating needs of

policy, taking policy decisions and effects of decisions. This a fortiori true

when untested unconventional monetary policy in gargantuan doses shocks the

economy and financial markets.

Table I-2, US,

Annual CPI Inflation ∆% 1914-2021

|

Year |

Annual ∆% |

|

1914 |

1.0 |

|

1915 |

1.0 |

|

1916 |

7.9 |

|

1917 |

17.4 |

|

1918 |

18.0 |

|

1919 |

14.6 |

|

1920 |

15.6 |

|

1921 |

-10.5 |

|

1922 |

-6.1 |

|

1923 |

1.8 |

|

1924 |

0.0 |

|

1925 |

2.3 |

|

1926 |

1.1 |

|

1927 |

-1.7 |

|

1928 |

-1.7 |

|

1929 |

0.0 |

|

1930 |

-2.3 |

|

1931 |

-9.0 |

|

1932 |

-9.9 |

|

1933 |

-5.1 |

|

1934 |

3.1 |

|

1935 |

2.2 |

|

1936 |

1.5 |

|

1937 |

3.6 |

|

1938 |

-2.1 |

|

1939 |

-1.4 |

|

1940 |

0.7 |

|

1941 |

5.0 |

|

1942 |

10.9 |

|

1943 |

6.1 |

|

1944 |

1.7 |

|

1945 |

2.3 |

|

1946 |

8.3 |

|

1947 |

14.4 |

|

1948 |

8.1 |

|

1949 |

-1.2 |

|

1950 |

1.3 |

|

1951 |

7.9 |

|

1952 |

1.9 |

|

1953 |

0.8 |

|

1954 |

0.7 |

|

1955 |

-0.4 |

|

1956 |

1.5 |

|

1957 |

3.3 |

|

1958 |

2.8 |

|

1959 |

0.7 |

|

1960 |

1.7 |

|

1961 |

1.0 |

|

1962 |

1.0 |

|

1963 |

1.3 |

|

1964 |

1.3 |

|

1965 |

1.6 |

|

1966 |

2.9 |

|

1967 |

3.1 |

|

1968 |

4.2 |

|

1969 |

5.5 |

|

1970 |

5.7 |

|

1971 |

4.4 |

|

1972 |

3.2 |

|

1973 |

6.2 |

|

1974 |

11.0 |

|

1975 |

9.1 |

|

1976 |

5.8 |

|

1977 |

6.5 |

|

1978 |

7.6 |

|

1979 |

11.3 |

|

1980 |

13.5 |

|

1981 |

10.3 |

|

1982 |

6.2 |

|

1983 |

3.2 |

|

1984 |

4.3 |

|

1985 |

3.6 |

|

1986 |

1.9 |

|

1987 |

3.6 |

|

1988 |

4.1 |

|

1989 |

4.8 |

|

1990 |

5.4 |

|

1991 |

4.2 |

|

1992 |

3.0 |

|

1993 |

3.0 |

|

1994 |

2.6 |

|

1995 |

2.8 |

|

1996 |

3.0 |

|

1997 |

2.3 |

|

1998 |

1.6 |

|

1999 |

2.2 |

|

2000 |

3.4 |

|

2001 |

2.8 |

|

2002 |

1.6 |

|

2003 |

2.3 |

|

2004 |

2.7 |

|

2005 |

3.4 |

|

2006 |

3.2 |

|

2007 |

2.8 |

|

2008 |

3.8 |

|

2009 |

-0.4 |

|

2010 |

1.6 |

|

2011 |

3.2 |

|

2012 |

2.1 |

|

2013 |

1.5 |

|

2014 |

1.6 |

|

2015 |

0.1 |

|

2016 |

1.3 |

|

2017 |

2.1 |

|

2018 |

2.4 |

|

2019 |

1.8 |

|

2020 |

1.2 |

|

2021 |

4.7 |

Source: US

Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart

I-14 provides the consumer price index excluding food and energy from 1957 to

2022. There is long-term inflation in the US without episodes of persistent

deflation.

Chart I-14, US, Consumer

Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 1957-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart

I-15 provides 12-month percentage changes of the consumer price index excluding

food and energy from 1958 to 2022. There are three waves of inflation in the

1970s during the Great Inflation. There is no episode of deflation.

Chart I-15, US, Consumer

Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA,

1958-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The

consumer price index of housing is in Chart I-16. There was also acceleration

during the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The index flattens after the global

recession in IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Housing prices collapsed under the weight of

construction of several times more housing than needed. Surplus housing

originated in subsidies and artificially low interest rates in the shock of

unconventional monetary policy in 2003 to 2004 in fear of deflation.

Chart I-16, US, Consumer

Price Index Housing, NSA, 1967-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart

I-17 provides 12-month percentage changes of the housing CPI. The Great

Inflation also had extremely high rates of housing inflation. Housing is

considered as potential hedge of inflation.

Chart I-17, US, Consumer

Price Index, Housing, 12- Month Percentage Change, NSA, 1968-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

ID Current

US Inflation. Consumer price inflation has fluctuated in recent months.

Table I-3 provides 12-month consumer price inflation in May 2022 and annual

equivalent percentage changes for the months from Mar 2022 to May 2022 of the

CPI and the core CPI. The final column provides inflation from Apr 2022 to May

2022. CPI inflation increased 8.6 percent in the 12 months ending in May 2022.

The annual equivalent rate from Mar 2022 to May 2022 was 10.5 percent in the

new episode of reversal and renewed positions of carry trades from zero

interest rates to commodities exposures with increasing fiscal imbalances; and

the monthly inflation rate of 1.0 percent annualizes at 12.7 percent with

oscillating carry trades at the margin. These inflation rates fluctuate in

accordance with inducement of risk appetite or frustration by risk aversion of

carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures. At the margin, the

decline in commodity prices in sharp recent risk aversion in commodities

markets caused lower inflation worldwide (with return in some countries in Dec

2012 and Jan-Feb 2013) that followed a jump in Aug-Sep 2012 because of the

relaxed risk aversion resulting from the bond-buying program of the European

Central Bank or Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120906_1.en.html). Carry trades moved away

from commodities into stocks with resulting weaker commodity prices and

stronger equity valuations. There is reversal of exposures in commodities but

with preferences of equities by investors. Geopolitical events in Eastern

Europe and the Middle East together with economic conditions worldwide are

inducing risk concerns in commodities at the margin. With zero or very low

interest rates, commodity prices would increase again in an environment of risk

appetite, as shown in past oscillating inflation. Excluding food and energy,

core CPI inflation was 6.0 percent in the 12 months ending in May 2022, 5.7

percent in annual equivalent from Mar 2022 to May 2022 and 0.6 percent in May

2022, which annualizes at 7.4 percent. There is no deflation in the US economy

that could justify further unconventional monetary policy, which is now

open-ended or forever with very low interest rates and cessation of bond-buying

by the central bank but with reinvestment of interest and principal, or QE→∞

even if the economy

grows back to potential. The FOMC is engaged in increases in the Fed balance

sheet. Financial repression of very low interest rates is constituted

protracted distortion of resource allocation by clouding risk/return decisions,

preventing the economy from expanding along its optimal growth path. On

Aug 27, 2020, the Federal Open Market Committee changed its Longer-Run Goals

and Monetary Policy Strategy, including the following (https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/review-of-monetary-policy-strategy-tools-and-communications-statement-on-longer-run-goals-monetary-policy-strategy.htm):

“The Committee judges that

longer-term inflation expectations that are well anchored at 2 percent foster

price stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the

Committee's ability to promote maximum employment in the face of significant

economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at

this level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent

over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been

running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely

aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.” The new

policy can affect relative exchange rates depending on relative inflation rates

and country risk issues. On Mar 6, 2022, the FOMC increased interest rates with

the following guidance (https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20220615a.htm): “The Committee seeks to achieve

maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run.

In support of these goals, the Committee decided to raise the target range for

the federal funds rate to 1‑1/2 to 1-3/4 percent and anticipates that ongoing

increases in the target range will be appropriate. In addition, the Committee

will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and

agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in the Plans for Reducing the

Size of the Federal Reserve's Balance Sheet that were issued in May. The

Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent

objective.”

In his classic

restatement of the Keynesian demand function in terms of “liquidity preference

as behavior toward risk,” James Tobin (http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1981/tobin-bio.html) identifies

the risks of low interest rates in terms of portfolio allocation (Tobin 1958,

86):

“The assumption

that investors expect on balance no change in the rate of interest has been

adopted for the theoretical reasons explained in section 2.6 rather than for reasons

of realism. Clearly investors do form expectations of changes in interest rates

and differ from each other in their expectations. For the purposes of dynamic

theory and of analysis of specific market situations, the theories of sections

2 and 3 are complementary rather than competitive. The formal apparatus of

section 3 will serve just as well for a non-zero expected capital gain or loss

as for a zero expected value of g. Stickiness of interest rate expectations

would mean that the expected value of g is a function of the rate of interest

r, going down when r goes down and rising when r goes up. In addition to the

rotation of the opportunity locus due to a change in r itself, there would be a

further rotation in the same direction due to the accompanying change in the

expected capital gain or loss. At low interest rates expectation of capital

loss may push the opportunity locus into the negative quadrant, so that the

optimal position is clearly no consols, all cash. At the other extreme,

expectation of capital gain at high interest rates would increase sharply the

slope of the opportunity locus and the frequency of no cash, all consols

positions, like that of Figure 3.3. The stickier the investor's expectations,

the more sensitive his demand for cash will be to changes in the rate of

interest (emphasis added).”

Tobin (1969)

provides more elegant, complete analysis of portfolio allocation in a general

equilibrium model. The major point is equally clear in a portfolio consisting

of only cash balances and a perpetuity or consol. Let g be the capital

gain, r the rate of interest on the consol and re the

expected rate of interest. The rates are expressed as proportions. The price of

the consol is the inverse of the interest rate, (1+re). Thus,

g = [(r/re) – 1]. The critical analysis of

Tobin is that at extremely low interest rates there is only expectation of

interest rate increases, that is, dre>0, such that there

is expectation of capital losses on the consol, dg<0. Investors move

into positions combining only cash and no consols. Valuations of risk

financial assets would collapse in reversal of long positions in carry trades

with short exposures in a flight to cash. There is no exit from a central bank

created liquidity trap without risks of financial crash and another global

recession. The net worth of the economy depends on interest rates. In theory,

“income is generally defined as the amount a consumer unit could consume (or

believe that it could) while maintaining its wealth intact” (Friedman 1957,

10). Income, Y, is a flow that is obtained by applying a rate of return,

r, to a stock of wealth, W, or Y = rW (Friedman

1957). According to a subsequent statement: “The basic idea is simply that

individuals live for many years and that therefore the appropriate constraint

for consumption is the long-run expected yield from wealth r*W.

This yield was named permanent income: Y* = r*W” (Darby

1974, 229), where * denotes permanent. The simplified relation of income and

wealth can be restated as:

W = Y/r

(1)

Equation (1) shows that as r goes to zero, r→0, W

grows without bound, W→∞. Unconventional monetary policy lowers interest

rates to increase the present value of cash flows derived from projects of

firms, creating the impression of long-term increase in net worth. An attempt

to reverse unconventional monetary policy necessarily causes increases in interest

rates, creating the opposite perception of declining net worth. As r→∞, W

= Y/r →0. There is no exit from unconventional monetary policy

without increasing interest rates with resulting pain of financial crisis and

adverse effects on production, investment and employment.

Table I-3, US,

Consumer Price Index Percentage Changes 12 months NSA and Annual Equivalent ∆%

|

|

% RI |

∆% 12 Months

May 2022/May |

∆% Annual

Equivalent Mar 2022 to May 2022 SA |

∆% May

2022/Apr 2022 SA |

|

CPI All Items |

100.000 |

8.6 |

10.5 |

1.1 |

|

CPI ex Food

and Energy |

78.324 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

0.6 |

% RI: Percent

Relative Importance

Source: US

Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

Table

I-4 provides relative important components of the consumer price index. The

relative important weights for May 2022 are in Table I-3.

Table I-4, US,

Relative Importance, 2009-2010 Weights, of Components in the Consumer Price

Index, US City Average, Dec 2012

|

All Items |

100.000 |

|

Food and

Beverages |

15.261 |

|

Food |

14.312 |

|

Food

at home |

8.898 |

|

Food

away from home |

5.713 |

|

Housing |

41.021 |

|

Shelter |

31.681 |

|

Rent

of primary residence |

6.545 |

|

Owners’ equivalent rent |

22.622 |

|

Apparel |

3.564 |

|

Transportation |

16.846 |

|

Private Transportation |

15.657 |

|

New

vehicles |

3.189 |

|

Used

cars and trucks |

1.844 |

|

Motor

fuel |

5.462 |

|

Gasoline |

5.274 |

|

Medical Care |

7.163 |

|

Medical care commodities |

1.714 |

|

Medical care services |

5.448 |

|

Recreation |

5.990 |

|

Education and

Communication |

6.779 |

|

Other Goods

and Services |

3.376 |

Refers to all

urban consumers, covering approximately 87 percent of the US population (see http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiovrvw.htm#item1). Source: US

Bureau of Labor Statistics http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiri2011.pdf http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiriar.htm http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiri2012.pdf

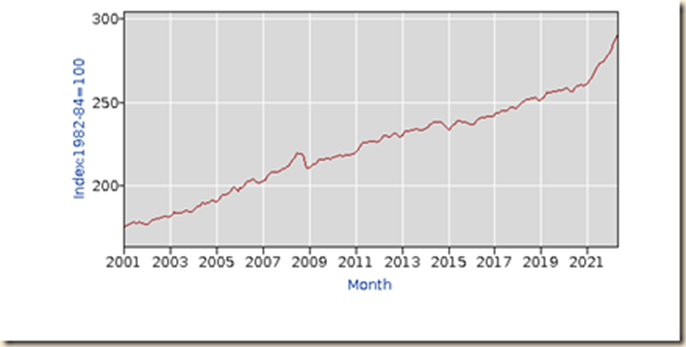

Chart

I-18 provides the US consumer price index for housing from 2001 to 2022.

Housing prices rose sharply during the decade until the bump of the global

recession and increased again in 2011-2012 with some stabilization in 2013.

There is renewed increase in 2014 followed by stabilization and renewed

increase in 2015-2022. The CPI excluding housing would likely show much higher

inflation. The commodity carry trades resulting from unconventional monetary

policy have compressed income remaining after paying for indispensable shelter.

Chart I-18, US, Consumer

Price Index, Housing, NSA, 2001-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart I-19 provides 12-month

percentage changes of the housing CPI. Percentage changes collapsed during the

global recession but have been rising into positive territory in 2011 and

2012-2013 but with the rate declining and then increasing into 2014. There is

decrease into 2015 followed by stability and marginal increase in 2016-2019

followed by initial decline in the global recession, with output in the US

reaching a high in Feb 2020 (https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions), in the lockdown of economic

activity in the COVID-19 event and the through in Apr 2020 (https://www.nber.org/news/business-cycle-dating-committee-announcement-july-19-2021) with sharp recovery.

Chart I-19, US, Consumer

Price Index, Housing, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

There

have been waves of consumer price inflation in the US in 2011 and into 2022 (https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2022/03/accelerating-inflation-throughout-world.html and earlier https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2022/02/us-gdp-growing-at-saar-of-70-percent-in.html) that are illustrated in

Table I-5. The first wave occurred in Jan-Apr 2011 and was caused by the

carry trade of commodity prices induced by unconventional monetary policy of

zero interest rates. Cheap money at zero opportunity cost in environment of

risk appetite was channeled into financial risk assets, causing increases in

commodity prices. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the all-items CPI

in Jan-Apr 2011 was 4.9 percent and the CPI excluding food and energy increased

at annual equivalent rate of 1.8 percent. The second wave occurred

during the collapse of the carry trade from zero interest rates to exposures in

commodity futures because of risk aversion in financial markets created by the

sovereign debt crisis in Europe. The annual equivalent rate of increase of the

all-items CPI dropped to 1.8 percent in May-Jun 2011 while the annual

equivalent rate of the CPI excluding food and energy increased at 2.4 percent.

In the third wave in Jul-Sep 2011, annual equivalent CPI inflation rose

to 3.2 percent while the core CPI increased at 2.4 percent. The fourth wave

occurred in the form of increase of the CPI all-items annual equivalent rate to

1.8 percent in Oct-Nov 2011 with the annual equivalent rate of the CPI

excluding food and energy remaining at 2.4 percent. The fifth wave

occurred in Dec 2011 to Jan 2012 with annual equivalent headline inflation of

1.8 percent and core inflation of 2.4 percent. In the sixth wave,

headline CPI inflation increased at annual equivalent 2.4 percent in Feb-Apr

2012 and 2.0 percent for the core CPI. The seventh wave in May-Jul

occurred with annual equivalent inflation of minus 1.2 percent for the headline

CPI in May-Jul 2012 and 2.0 percent for the core CPI. The eighth wave is

with annual equivalent inflation of 6.8 percent in Aug-Sep 2012 but 5.7 percent

including Oct. In the ninth wave, annual equivalent inflation in Nov

2012 was minus 2.4 percent under the new shock of risk aversion and 0.0 percent

in Dec 2012 with annual equivalent of 0.0 percent in Nov 2012-Jan 2013 and 2.0

percent for the core CPI. In the tenth wave, annual equivalent of the

headline CPI was 6.2 percent in Feb 2013 and 1.2 percent for the core CPI. In

the eleventh wave, annual equivalent was minus 3.0 percent in Mar-Apr

2013 and 0.6 percent for the core index. In the twelfth wave, annual

equivalent inflation was 1.4 percent in May-Sep 2013 and 2.2 percent for the

core CPI. In the thirteenth wave, annual equivalent CPI inflation in

Oct-Nov 2013 was 1.8 percent and 1.8 percent for the core CPI. Inflation

returned in the fourteenth wave at 2.4 percent for the headline CPI

index and 1.8 percent for the core CPI in annual equivalent for Dec 2013 to Mar

2014. In the fifteenth wave, inflation moved to annual equivalent 1.8

percent for the headline index in Apr-Jul 2014 and 2.1 percent for the core

index. In the sixteenth wave, annual equivalent inflation was 0.0

percent in Aug 2014 and 1.2 percent for the core index. In the seventeenth

wave, annual equivalent inflation was 0.0 percent for the headline CPI and

2.4 percent for the core in Sep-Oct 2014. In the eighteenth wave, annual

equivalent inflation was minus 4.3 percent for the headline index in Nov

2014-Jan 2015 and 1.2 percent for the core. In the nineteenth wave,

annual equivalent inflation was 3.2 percent for the headline index and 2.2

percent for the core index in Feb-Jun 2015. In the twentieth wave,

annual equivalent inflation was at 2.4 percent in Jul 2015 for the headline and

core indexes. In the twenty-first wave, headline consumer prices

decreased at 1.2 percent in annual equivalent in Aug-Sep 2015 while core prices

increased at annual equivalent 1.8 percent. In the twenty-second wave,

consumer prices increased at annual equivalent 1.2 percent for the central

index and 2.4 percent for the core in Oct-Nov 2015. In the twenty-third wave,

annual equivalent inflation was minus 0.6 percent for the headline CPI in Dec

2015 to Jan 2016 and 1.8 percent for the core. In the twenty-fourth wave,

annual equivalent was minus 1.2 percent and 2.4 percent for the core in Feb

2016. In the twenty-fifth wave, annual equivalent inflation was at 4.3

percent for the central index in Mar-Apr 2016 and at 3.0 percent for the core

index. In the twenty-sixth wave, annual equivalent inflation was 3.0

percent for the central CPI in May-Jun 2016 and 2.4 percent for the core CPI.

In the twenty-seventh wave, annual equivalent inflation was minus 1.2

percent for the central CPI and 1.2 percent for the core in Jul 2016. In the twenty-eighth

wave, annual equivalent inflation was 2.4 percent for the headline CPI in

Aug 2016 and 2.4 percent for the core. In the twenty-ninth wave, CPI

prices increased at annual equivalent 3.0 percent in Sep-Oct 2016 while the

core CPI increased at 1.8 percent. In the thirtieth wave, annual

equivalent CPI prices increased at 2.4 percent in Nov-Dec 2016 while the core

CPI increased at 1.8 percent. In the thirty-first wave, CPI prices

increased at annual equivalent 4.9 percent in Jan 2017 while the core index

increased at 2.4 percent. In the thirty-second wave, CPI prices changed

at annual equivalent 2.4 percent in Feb 2017 while the core increased at 2.4

percent. In the thirty-third wave, CPI prices changed at annual

equivalent 0.0 percent in Mar 2017 while the core index changed at 0.0 percent.

In the thirty-fourth wave, CPI prices increased at 1.2 percent annual

equivalent in Apr 2017 while the core index increased at 1.2 percent. In the thirty-fifth

wave, CPI prices changed at 0.0 annual equivalent in May-Jun 2017 while

core prices increased at 1.2 percent. In the thirty-sixth wave, CPI

prices changed at annual equivalent 0.0 percent in Jul 2017 while core prices

increased at 1.2 percent. In the thirty-seventh wave, CPI prices

increased at annual equivalent 5.5 percent in Aug-Sep 2017 while core prices

increased at 1.8 percent. In the thirty-eighth wave, CPI prices

increased at 2.4 percent annual equivalent in Oct-Nov 2017 while core prices

increased at 2.4 percent. In the thirty-ninth wave, CPI prices increased

at 3.7 percent annual equivalent in Dec 2017-Feb 2018 while core prices

increased at 2.8 percent. In the fortieth wave, CPI prices increased at

1.2 percent annual equivalent in Mar 2018 while core prices increased at 2.4

percent. In the forty-first wave, CPI prices increased at 3.0 percent

annual equivalent in Apr-May 2018 while core prices increased at 2.4 percent.

In the forty-second wave, CPI prices increased at 1.8 percent in Jun-Sep

2018 while core prices increased at 1.8 percent. In the forty-third wave,

CPI prices increased at annual equivalent 2.4 percent in Oct 2018 while core

prices increased at 2.4 percent. In the forty-fourth wave, CPI prices

changed at minus 0.4 percent annual equivalent in Nov 2018-Jan 2019 while core

prices increased at 2.4 percent. In the forty-fifth wave, CPI prices

increased at 4.5 percent annual equivalent in Feb-Apr 2019 while core prices

increased at 2.0 percent. In the forty-sixth wave, CPI prices increased

at 0.6 percent annual equivalent in May-Jun 2019 while core prices increased at

1.8 percent. In the forty-seventh wave, CPI prices increased at 2.4

percent annual equivalent in Jul 2019 while core prices increased at 2.4

percent. In the forty-eighth wave, CPI prices increased at 1.8 percent

annual equivalent in Aug-Sep 2019 while core prices increased at 2.4 percent.

In the forty-ninth wave, CPI prices increased at 2.8 percent annual

equivalent in Oct-Dec 2019 while core prices increased at 2.0 percent. In the fiftieth

wave, CPI prices increased at 1.8 percent annual equivalent in Jan-Feb 2020

and core prices at 3.0 percent. In the fifty-first wave, CPI prices

decreased at annual equivalent 4.7 percent in Mar-May 2020 while core prices

decreased at 2.4 percent. In the fifty-second wave, CPI prices increased

at 6.2 percent annual equivalent in Jun-Jul 2020 and core prices increased at

4.9 percent. In the fifty-third wave, CPI prices increased at annual

equivalent 3.7 percent and core prices increased at 3.7 percent in Aug-Sep

2020. In the fifty-fourth wave, CPI prices increased at 1.2 percent

annual equivalent and core prices at 1.2 percent in Oct 2020. In the fifty-fifth

wave, CPI prices increased at 2.4 percent annual equivalent in Nov 2020-Jan

2021 and core prices at 1.2 percent. In the fifty-sixth wave, CPI prices

increased at annual equivalent 6.2 percent in Feb-Mar 2021 and core prices at

3.0 percent. In the fifty-seventh wave, CPI prices increased at annual

equivalent 9.2 percent in Apr-Jun 2021 and core prices at 10.0 percent. In the fifty-eight

wave, CPI prices increased at annual equivalent 4.9 percent in Jul-Sep 2021

and core prices at 3.2 percent. In the fifty-ninth wave, CPI prices

increased at annual equivalent 10.0 percent in Oct-Nov 2021 while core prices

increased at 6.8 percent. In the sixtieth wave, CPI prices increased at

annual equivalent 8.3 percent and core prices increased at 7.0 percent in Dec

2021-Feb 2022. In the sixty-first wave, CPI prices increased at annual

equivalent 15.4 percent and core prices at 3.7 percent in Mar 2022. In the sixty-second

wave, CPI prices increased at annual equivalent 3.7 percent in Apr 2022 and

core prices at 7.4 percent. In the sixty-third wave, CPI prices

increased at annual equivalent 12.7 percent in May 2022 and core prices at 7.4

percent. The conclusion is that inflation accelerates and decelerates in

unpredictable fashion because of shocks or risk aversion and portfolio

reallocations in carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity

derivatives.

Table I-5, US,

Headline and Core CPI Inflation Monthly SA and 12 Months NSA ∆%

|

|

All

Items SA Month |

All Items NSA

12 month |

Core SA |

Core NSA |

|

May 2022 |

1.0 |

8.6 |

0.6 |

6.0 |

|

AE May |

12.7 |

|

7.4 |

|

|

Apr |

0.3 |

8.3 |

0.6 |

6.2 |

|

AE Apr |

3.7 |

|

7.4 |

|

|

Mar |

1.2 |

8.5 |

0.3 |

6.5 |

|

AE Mar |

15.4 |

|

3.7 |

|

|

Feb |

0.8 |

7.9 |

0.5 |

6.4 |

|

Jan |

0.6 |

7.5 |

0.6 |

6.0 |

|

Dec 2021 |

0.6 |

7.0 |

0.6 |

5.5 |

|

AE Dec-Feb |

8.3 |

|

7.0 |

|

|

Nov |

0.7 |

6.8 |

0.5 |

4.9 |

|

Oct |

0.9 |

6.2 |

0.6 |

4.6 |

|

AE Oct-Nov |

10.0 |

|

6.8 |

|

|

Sep |

0.4 |

5.4 |

0.3 |

4.0 |

|

Aug |

0.3 |

5.3 |

0.2 |

4.0 |

|

Jul |

0.5 |

5.4 |

0.3 |

4.3 |

|

AE Jul-Sep |

4.9 |

|

3.2 |

|

|

Jun |

0.9 |

5.4 |

0.8 |

4.5 |

|

May |

0.7 |

5.0 |

0.7 |

3.8 |

|

Apr |

0.6 |

4.2 |

0.9 |

3.0 |

|

AE Apr-Jun |

9.2 |

|

10.0 |

|

|

Mar |

0.6 |

2.6 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

|

Feb |

0.4 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

1.3 |

|

AE ∆% Feb-Mar |

6.2 |

|

3.0 |

|

|

Jan |

0.2 |

1.4 |

0.0 |

1.4 |

|

Dec 2020 |

0.3 |

1.4 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Nov |

0.1 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

|

AE ∆% Nov-Jan |

2.4 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Oct |

0.1 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

AE ∆% Oct |

1.2 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Sep |

0.2 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

Aug |

0.4 |

1.3 |

0.4 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Aug-Sep |

3.7 |

|

3.7 |

|

|

Jul |

0.5 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

1.6 |

|

Jun |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

|

AE ∆% Jun-Jul |

6.2 |

|

4.9 |

|

|

May |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

-0.1 |

1.2 |

|

Apr |

-0.8 |

0.3 |

-0.4 |

1.4 |

|

Mar |

-0.3 |

1.5 |

-0.1 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Mar-May |

-4.7 |

|

-2.4 |

|

|

Feb |

0.1 |

2.3 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

|

Jan |

0.2 |

2.5 |

0.3 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% Jan-Feb |

1.8 |

|

3.0 |

|

|

Dec 2019 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

0.1 |

2.3 |

|

Nov |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

Oct |

0.3 |

1.8 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% Oct-Dec |

2.8 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Sep |

0.2 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

|

Aug |

0.1 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

|

AE ∆% Aug-Sep |

1.8 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jul |

0.2 |

1.8 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Jul |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jun |

0.0 |

1.6 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

May |

0.1 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

|

AE ∆% May-Jun |

0.6 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Apr |

0.4 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

Mar |

0.4 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

Feb |

0.3 |

1.5 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Feb-Apr |

4.5 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Jan |

0.0 |

1.6 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Dec 2018 |

0.0 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Nov |

-0.1 |

2.2 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Nov-Jan |

-0.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Oct |

0.2 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Oct |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Sep |

0.2 |

2.3 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Aug |

0.2 |

2.7 |

0.1 |

2.2 |

|

Jul |

0.1 |

2.9 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

|

Jun |

0.1 |

2.9 |

0.1 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% Jun-Sep |

1.8 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

May |

0.3 |

2.8 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Apr |

0.2 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Apr-May |

3.0 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Mar |

0.1 |

2.4 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Mar |

1.2 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Feb |

0.3 |

2.2 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Jan |

0.4 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

|

Dec 2017 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Dec-Feb |

3.7 |

|

2.8 |

|

|

Nov |

0.3 |

2.2 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

Oct |

0.1 |

2.0 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Oct-Nov |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Sep |

0.5 |

2.2 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

Aug |

0.4 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Aug-Sep |

5.5 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Jul |

0.0 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Jul |

0.0 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Jun |

0.1 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

May |

-0.1 |

1.9 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% May-Jun |

0.0 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Apr |

0.1 |

2.2 |

0.1 |

1.9 |

|

AE ∆% Apr |

1.2 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Mar |

0.0 |

2.4 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

|

AE ∆% Mar |

0.0 |

|

0.0 |

|

|

Feb |

0.2 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Feb |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jan |

0.4 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% Jan |

4.9 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Dec 2016 |

0.3 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Nov |

0.1 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Nov-Dec |

2.4 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Oct |

0.2 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

|

Sep |

0.3 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Sep-Oct |

3.0 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Aug |

0.2 |

1.1 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆ Aug |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jul |

-0.1 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Jul |

-1.2 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Jun |

0.3 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

May |

0.2 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% May-Jun |

3.0 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Apr |

0.4 |

1.1 |

0.3 |

2.1 |

|

Mar |

0.3 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Mar-Apr |

4.3 |

|

3.0 |

|

|

Feb |

-0.1 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% Feb |

-1.2 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jan |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Dec 2015 |

-0.1 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Dec-Jan |

-0.6 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Nov |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

Oct |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

AE ∆% Oct-Nov |

1.2 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Sep |

-0.2 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

Aug |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Aug-Sep |

-1.2 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Jul |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Jul |

2.4 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jun |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

May |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

Apr |

0.1 |

-0.2 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Mar |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Feb |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Feb-Jun |

3.2 |

|

2.2 |

|

|

Jan |

-0.6 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Dec 2014 |

-0.3 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Nov |

-0.2 |

1.3 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Nov-Jan |

-4.3 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Oct |

0.0 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Sep |

0.0 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Sep-Oct |

0.0 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Aug |

0.0 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Aug |

0.0 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Jul |

0.1 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

Jun |

0.1 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

1.9 |

|

May |

0.2 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

Apr |

0.2 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Apr-Jul |

1.8 |

|

2.1 |

|

|

Mar |

0.2 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

Feb |

0.1 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Jan |

0.2 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

1.6 |

|

Dec 2013 |

0.3 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Dec-Mar |

2.4 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Nov |

0.2 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

Oct |

0.1 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% Oct-Nov |

1.8 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Sep |

0.0 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

Aug |

0.2 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Jul |

0.2 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

|

Jun |

0.2 |

1.8 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

|

May |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

|

AE ∆% May-Sep |

1.4 |

|

2.2 |

|

|

Apr |

-0.2 |

1.1 |

0.0 |

1.7 |

|

Mar |

-0.3 |

1.5 |

0.1 |

1.9 |

|

AE ∆% Mar-Apr |

-3.0 |

|

0.6 |

|

|

Feb |

0.5 |

2.0 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

|

AE ∆% Feb |

6.2 |

|

1.2 |

|

|

Jan |

0.2 |

1.6 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

Dec 2012 |

0.0 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

Nov |

-0.2 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

1.9 |

|

AE ∆% Nov-Jan |

0.0 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Oct |

0.3 |

2.2 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

Sep |

0.5 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

2.0 |

|

Aug |

0.6 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

1.9 |

|

AE ∆% Aug-Oct |

5.7 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Jul |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

Jun |

-0.1 |

1.7 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

May |

-0.2 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

2.3 |

|

AE ∆% May-Jul |

-1.2 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Apr |

0.2 |

2.3 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

Mar |

0.2 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

Feb |

0.2 |

2.9 |

0.1 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Feb-Apr |

2.4 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

Jan |

0.3 |

2.9 |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

Dec 2011 |

0.0 |

3.0 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

AE ∆% Dec-Jan |

1.8 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Nov |

0.2 |

3.4 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

|

Oct |

0.1 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

|

AE ∆% Oct-Nov |

1.8 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Sep |

0.2 |

3.9 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

|

Aug |

0.3 |

3.8 |

0.3 |

2.0 |

|

Jul |

0.3 |

3.6 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

AE ∆% Jul-Sep |

3.2 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Jun |

0.0 |

3.6 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

|

May |

0.3 |

3.6 |

0.2 |

1.5 |

|

AE ∆%

May-Jun |

1.8 |

|

2.4 |

|

|

Apr |

0.5 |

3.2 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

|

Mar |

0.5 |

2.7 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

|

Feb |

0.3 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Jan |

0.3 |

1.6 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

|

AE ∆%

Jan-Apr |

4.9 |

|

1.8 |

|

|

Dec 2010 |

0.4 |

1.5 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

|

Nov |

0.3 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

|

Oct |

0.3 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

|

Sep |

0.2 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

|

Aug |

0.1 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

|

Jul |

0.2 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

|

Jun |

0.0 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

|

May |

-0.1 |

2.0 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

|

Apr |

0.0 |

2.2 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

|

Mar |

0.0 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

1.1 |

|

Feb |

-0.1 |

2.1 |

0.0 |

1.3 |

|

Jan |

0.1 |

2.6 |

-0.1 |

1.6 |

Note: Core:

excluding food and energy; AE: annual equivalent

Source: US

Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

The behavior of the US

consumer price index NSA from 2001 to 2022 is in Chart I-20. Inflation in the

US is very dynamic without deflation risks that would justify symmetric

inflation targets. The hump in 2008 originated in the carry trade from interest

rates dropping to zero into commodity futures. There is no other explanation

for the increase of the Cushing OK Crude Oil Future Contract 1 from

$55.64/barrel on Jan 9, 2007 to $145.29/barrel on July 3, 2008 during deep

global recession, collapsing under a panic of flight into government

obligations and the US dollar to $37.51/barrel on Feb 13, 2009 and then rising

by carry trades to $113.93/barrel on Apr 29, 2012, collapsing again and then

recovering again to $105.23/barrel, all during mediocre economic recovery with

peaks and troughs influenced by bouts of risk appetite and risk aversion (data

from the US Energy Information Administration EIA, https://www.eia.gov/). The unwinding of the carry

trade with the TARP announcement of toxic assets in banks channeled cheap money

into government obligations (see Cochrane and Zingales 2009). There is sharp

increase in 2021 and into 2022.

Chart I-20, US, Consumer

Price Index, NSA, 2001-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart

I-21 provides 12-month percentage changes of the consumer price index from 2001

to 2022. There was no deflation or threat of deflation from 2008 into 2009.

Commodity prices collapsed during the panic of toxic assets in banks. When

stress tests in 2009 revealed US bank balance sheets in much stronger position,

cheap money at zero opportunity cost exited government obligations and flowed

into carry trades of risk financial assets. Increases in commodity prices drove

again the all-items CPI with interruptions during risk aversion originating in

multiple fears but especially from the sovereign debt crisis of Europe. There

are sharp increases in 2021-2022.

Chart I-21, US, Consumer

Price Index, 12-Month Percentage Change, NSA, 2001-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

The trend of increase of the

consumer price index excluding food and energy in Chart I-22 does not reveal

any threat of deflation that would justify symmetric inflation targets. There

are mild oscillations in a neat upward trend.

Chart I-22, US, Consumer

Price Index Excluding Food and Energy, NSA, 2001-2022

Source: US Bureau of Labor

Statistics https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

Chart

I-23 provides 12-month percentage change of the consumer price index excluding

food and energy. Past-year rates of inflation fell toward 1 percent from 2001

into 2003 because of the recession and the decline of commodity prices

beginning before the recession with declines of real oil prices. Near zero

interest rates with fed funds at 1 percent between Jun 2003 and Jun 2004

stimulated carry trades of all types, including in buying homes with subprime

mortgages in expectation that low interest rates forever would increase home

prices permanently, creating the equity that would permit the conversion of

subprime mortgages into creditworthy mortgages (Gorton 2009EFM; see https://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/causes-of-2007-creditdollar-crisis.html).

Inflation rose and then collapsed during the unwinding of carry trades and the housing

debacle of the global recession. Carry trades into 2011 and 2012 gave a new

impulse to CPI inflation, all items and core. Symmetric inflation targets