Growth Uncertainties, Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars below Trend, Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures World Cyclical Slow Growth and Global Recession Risk

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

Note: The complete analysis of the world economy and finance will resume after a brief sabbatical. Selected sections will be available until resumption of the complete analysis.

I Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth with GDP Two Trillion Dollars Below Trend

IA Mediocre Cyclical United States Economic Growth

IA1 Contracting Real Private Fixed Investment

IA2 Swelling Undistributed Corporate Profits

II Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB1 Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures

IB2 Financial Repression

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

Appendixes

Appendix I The Great Inflation

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIG Appendix on Deficit Financing of Growth and the Debt Crisis

IIIGA Monetary Policy with Deficit Financing of Economic Growth

IIIGB Adjustment during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s

II Stagnating Real Disposable Income and Consumption Expenditures. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides important revisions and enhancements of data on personal income and outlays since 1929 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). There are waves of changes in personal income and expenditures in Table IB-1 that correspond somewhat to inflation waves observed worldwide (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html) because of the influence through price indexes. Data are distorted in Nov and Dec 2012 by the rush to realize income of all forms in anticipation of tax increases beginning in Jan 2013. There is major distortion in Jan 2013 because of higher contributions in payrolls to government social insurance that caused sharp reduction in personal income and disposable personal income. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) explains as follows (page 3 http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0313.pdf):

“The February and January [2013] changes in disposable personal income (DPI) mainly reflected the effect of special factors in January, such as the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday” and the acceleration of bonuses and personal dividends to November and to December [2012] in anticipation of changes in individual tax rates.”

In the first wave in Jan-Apr 2011 with relaxed risk aversion, nominal personal income (NPI) increased at the annual equivalent rate of 8.1 percent, nominal disposable personal income (NDPI) at 5.2 percent and nominal personal consumption expenditures (NPCE) at 5.9 percent. Real disposable income (RDPI) increased at the annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent and real personal consumption expenditures (RPCE) rose at annual equivalent 1.5 percent. In the second wave in May-Aug 2011 under risk aversion, NPI rose at annual equivalent 4.9 percent, NPDI at 4.9 percent and NPCE at 3.7 percent. RDPI increased at 1.8 percent annual equivalent and RPCE at 0.9 percent annual equivalent. With mixed shocks of risk aversion in the third wave from Sep to Dec 2011, NPI rose at 2.4 percent annual equivalent, NDPI at 2.4 percent and NPCE at 2.1 percent. RDPI increased at 1.5 percent annual equivalent and RPCE at 1.5 percent annual equivalent. In the fourth wave from Jan to Mar 2012, NPI increased at 9.6 percent annual equivalent and NDPI at 8.7 percent. Real disposable income (RDPI) is more dynamic in the revisions, growing at 5.7 percent annual equivalent and RPCE at 3.7 percent. The policy of repressing savings with zero interest rates stimulated growth of nominal consumption (NPCE) at the annual equivalent rate of 6.2 percent and real consumption (RPCE) at 3.7 percent. In the fifth wave in Apr-Jul 2012, NPI increased at annual equivalent 0.9 percent, NDPI at 0.9 percent and RDPI at 0.0 percent. Financial repression failed to stimulate consumption with NPCE growing at 2.1 percent annual equivalent and RPCE at 1.8 percent. In the sixth wave in Aug-Oct 2012, in another wave of carry trades into commodity futures, NPI increased at 7.9 percent annual equivalent and NDPI increased at 7.0 percent while real disposable income (RDPI) increased at 3.7 percent annual equivalent. Data for Nov-Dec 2012 have illusory increases: “Personal income in November and December was boosted by accelerated and special dividend payments to persons and by accelerated bonus payments and other irregular pay in private wages and salaries in anticipation of changes in individual income tax rates. Personal income in December was also boosted by lump-sum social security benefit payments” (page 2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1212.pdf). In the seventh wave, anticipations of tax increases in Jan 2013 caused exceptional income gains that increased personal income to annual equivalent 28.3 percent in Nov-Dec 2012, nominal disposable income at 27.5 percent and real disposable personal income at 28.3 percent with likely effects on nominal personal consumption that increased at 2.4 percent and real personal consumption at 3.0 percent with subdued prices. The numbers in parentheses show that without the exceptional effects NDPI (nominal disposable personal income) increased at 5.5 percent and RDPI (real disposable personal income) at 8.7 percent. In the eighth wave, nominal personal income fell 5.1 percent in Jan 2013 or at the annual equivalent rate of decline of 46.6 percent; nominal disposable personal income fell 5.8 percent or at the annual equivalent rate of decline of 51.2 percent; real disposable income fell 5.5 percent or at the annual rate of decline of 51.8 percent; nominal personal consumption expenditures increased 0.5 percent or at the annual equivalent rate of 6.2 percent; and real personal consumption expenditures increased 0.4 percent or at the annual equivalent rate of 4.9 percent. The savings rate fell significantly from 10.5 percent in Dec 2012 to 4.5 percent in Jan 2013. The Bureau of Economic Analysis explains as follows (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0113.pdf 3):

“Contributions for government social insurance -- a subtraction in calculating personal income -- increased $126.7 billion in January, compared with an increase of $6.3 billion in December. The

January estimate reflected increases in both employer and employee contributions for government social insurance. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance reflected the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday,” that increased the social security contribution rate for employees and self-employed workers by 2.0 percentage points, or $114.1 billion at an annual rate. For additional information, see FAQ on “How did the expiration of the payroll tax holiday affect personal income for January 2013?” at www.bea.gov. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance also reflected an increase in the monthly premiums paid by participants in the supplementary medical insurance program, in the hospital insurance provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and in the social security taxable wage base; together, these changes added $12.8 billion to January. As noted above, employer contributions were boosted $5.9 billion in January, so the total contribution of special factors to the January change in contributions for government social insurance was $132.8 billion”

Further explanation is provided by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0213.pdf 2-3):

“Contributions for government social insurance -- a subtraction in calculating personal income --increased $6.4 billion in February, compared with an increase of $126.8 billion in January. The

January estimate reflected increases in both employer and employee contributions for government social insurance. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance reflected the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday,” that increased the social security contribution rate for employees and self-employed workers by 2.0 percentage points, or $114.1 billion at an annual rate. For additional information, see FAQ on “How did the expiration of the payroll tax holiday affect personal income for January 2013?” at www.bea.gov. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance also reflected an increase in the monthly premiums paid by participants in the supplementary medical insurance program, in the hospital insurance provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and in the social security taxable wage base; together, these changes added $12.9 billion to January. Employer contributions were boosted $5.9 billion in January, which reflected increases in the social security taxable wage base (from $110,100 to $113,700), in the tax rates paid by employers to state unemployment insurance, and in employer contributions for the federal unemployment tax and for pension guaranty. The total contribution of special factors to the January change in contributions for government social insurance was $132.9 billion. The January change in disposable personal income (DPI) mainly reflected the effect of special factors, such as the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday” and the acceleration of bonuses and personal dividends to December in anticipation of changes in individual tax rates. Excluding these special factors and others, which are discussed more fully below, DPI increased $46.8 billion in February, or 0.4 percent, after increasing $15.8 billion, or 0.1 percent, in January.”

The increase was provided in the “fiscal cliff” law H.R. 8 American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-112hr8eas/pdf/BILLS-112hr8eas.pdf). In the ninth wave in Feb-Mar 2013, nominal personal income increased at 7.4 percent and nominal disposable income at 6.8 percent annual equivalent, while real disposable income increased at 5.5 percent annual equivalent. Nominal personal consumption expenditures grew at 4.3 percent annual equivalent and real personal consumption expenditures at 2.4 percent annual equivalent. The savings rate collapsed from 7.1 percent in Oct 2012, 8.2 percent in Nov 2012 and 10.5 percent in Dec 2012 to 4.5 percent in Jan 2013, 4.7 percent in Feb 2013 and 4.9 percent in Mar 2013. In the tenth wave from Apr to Sep 2013, personal income grew at 3.7 percent annual equivalent, nominal disposable income increased at annual equivalent 3.9 percent and nominal personal consumption expenditures at 2.8 percent. Real disposable income grew at 3.2 percent annual equivalent and real personal consumption expenditures at 2.2 percent. In the eleventh wave, nominal personal income fell at 1.2 percent annual equivalent in Oct 2013, nominal disposable income at 2.4 percent and real disposable income at 3.5 percent. Nominal personal consumption expenditures increased at 4.9 percent annual equivalent and real personal consumption expenditures at 3.7 percent. In the twelfth wave, nominal personal income increased at 3.7 percent annual equivalent in Nov 2013, nominal disposable income at 2.4 percent and nominal personal consumption expenditures at 7.4 percent. Real disposable income increased at annual equivalent 7.4 percent and real personal consumption expenditures at 6.2 percent. In the thirteenth wave, nominal personal income changed at 0.0 percent annual equivalent in Dec 2013 and nominal disposable income fell at 1.2 percent while real disposable income fell at 2.4 percent annual equivalent. Nominal personal consumption expenditures increased at 1.2 percent annual equivalent and 0.0 percent for real personal consumption expenditures. In the fourteenth wave, nominal personal income increased at 5.7 percent annual equivalent in Jan-Aug 2014, nominal disposable income at 5.9 percent and nominal consumption expenditures at 3.8 percent. Real disposable personal income increased at 4.3 percent and real personal consumption expenditures at 2.3 percent. In the fifteenth wave, nominal personal income increased at 2.4 percent in annual equivalent in Sep 2014 and nominal disposable income at 1.2 percent. Real disposable income changed at 0.0 percent in annual equivalent in Sep 2014. Nominal personal consumption fell at 2.4 percent annual equivalent in Sep 2014 and real personal consumption expenditures fell at 2.4 percent.

The United States economy has grown at the average yearly rate of 3 percent per year and 2 percent per year in per capita terms from 1870 to 2010, as measured by Lucas (2011May). An important characteristic of the economic cycle in the US has been rapid growth in the initial phase of expansion after recessions.

Inferior performance of the US economy and labor markets is the critical current issue of analysis and policy design. Long-term economic performance in the United States consisted of trend growth of GDP at 3 percent per year and of per capita GDP at 2 percent per year as measured for 1870 to 2010 by Robert E Lucas (2011May). The economy returned to trend growth after adverse events such as wars and recessions. The key characteristic of adversities such as recessions was much higher rates of growth in expansion periods that permitted the economy to recover output, income and employment losses that occurred during the contractions. Over the business cycle, the economy compensated the losses of contractions with higher growth in expansions to maintain trend growth of GDP of 3 percent and of GDP per capita of 2 percent. The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. US economic growth has been at only 2.3 percent on average in the cyclical expansion in the 21 quarters from IIIQ2009 to IIIQ2014. Boskin (2010Sep) measures that the US economy grew at 6.2 percent in the first four quarters and 4.5 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the second quarter of 1975; and at 7.7 percent in the first four quarters and 5.8 percent in the first 12 quarters after the trough in the first quarter of 1983 (Professor Michael J. Boskin, Summer of Discontent, Wall Street Journal, Sep 2, 2010 http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703882304575465462926649950.html). There are new calculations using the revision of US GDP and personal income data since 1929 by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) and the first estimate of GDP for IIIQ2014 (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2014/pdf/gdp3q14_adv.pdf). The average of 7.7 percent in the first four quarters of major cyclical expansions is in contrast with the rate of growth in the first four quarters of the expansion from IIIQ2009 to IIQ2010 of only 2.7 percent obtained by diving GDP of $14,745.9 billion in IIQ2010 by GDP of $14,355.6 billion in IIQ2009 {[$14,745.9/$14,355.6 -1]100 = 2.7%], or accumulating the quarter on quarter growth rates (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html). The expansion from IQ1983 to IVQ1985 was at the average annual growth rate of 5.9 percent, 5.4 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1986, 5.2 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1986, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IIQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IIIQ1987, 5.0 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1987, 4.9 percent from IQ1983 to IQ1988 and at 7.8 percent from IQ1983 to IVQ1983 (Section I and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/financial-volatility-mediocre-cyclical.html). The US maintained growth at 3.0 percent on average over entire cycles with expansions at higher rates compensating for contractions. Growth at trend in the entire cycle from IVQ2007 to IIIQ2014 would have accumulated to 23.0 percent. GDP in IIIQ2014 would be $18,438.0 billion (in constant dollars of 2009) if the US had grown at trend, which is higher by $2,287.4 billion than actual $16,150.6 billion. There are about two trillion dollars of GDP less than at trend, explaining the 26.5 million unemployed or underemployed equivalent to actual unemployment of 16.1 percent of the effective labor force (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/world-financial-turbulence-twenty-seven.html and earlier http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/competitive-monetary-policy-and.html). US GDP in IIIQ2014 is 12.4 percent lower than at trend. US GDP grew from $14,991.8 billion in IVQ2007 in constant dollars to $16,150.6 billion in IIIQ2014 or 7.7 percent at the average annual equivalent rate of 1.1 percent. Cochrane (2014Jul2) estimates US GDP at more than 10 percent below trend. The US missed the opportunity to grow at higher rates during the expansion and it is difficult to catch up because growth rates in the final periods of expansions tend to decline. The US missed the opportunity for recovery of output and employment always afforded in the first four quarters of expansion from recessions. Zero interest rates and quantitative easing were not required or present in successful cyclical expansions and in secular economic growth at 3.0 percent per year and 2.0 percent per capita as measured by Lucas (2011May). There is cyclical uncommonly slow growth in the US instead of allegations of secular stagnation. There is similar behavior in manufacturing. The long-term trend is growth at average 3.3 percent per year from Jan 1919 to Sep 2014. Growth at 3.3 percent per year would raise the NSA index of manufacturing output from 99.2392 in Dec 2007 to 123.5550 in Sep 2014. The actual index NSA in Sep 2014 is 102.0228, which is 17.4 percent below trend. Manufacturing output grew at average 2.3 percent between Dec 1986 and Dec 2013, raising the index at trend to 115.7028 in Sep 2014. The output of manufacturing at 102.0228 in Sep 2014 is 11.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation. The output of manufacturing at 101.5145 in Aug 2014 is 13.8 percent below trend under this alternative calculation.

Table IB-1, US, Percentage Change from Prior Month Seasonally Adjusted of Personal Income, Disposable Income and Personal Consumption Expenditures %

| NPI | NDPI | RDPI | NPCE | RPCE | |

| 2014 | |||||

| Sep | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| AE ∆% Sep | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | -2.4 | -2.4 |

| Aug | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Jun | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| May | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Apr | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | -0.1 |

| Mar | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Feb | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Jan | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | -0.2 | -0.3 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Aug | 5.7 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 2.3 |

| 2013 | |||||

| Dec | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| AE ∆% Dec | 0.0 | -1.2 | -2.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Nov | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| AE ∆% Nov | 3.7 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 7.4 | 6.2 |

| Oct | -0.1 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| AE ∆% Oct | -1.2 | -2.4 | -3.5 | 4.9 | 3.7 |

| Sep | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Aug | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Jul | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Jun | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| May | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Apr | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| AE ∆% Apr-Sep | 3.7 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.2 |

| Mar | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Feb | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Mar | 7.4 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 2.4 |

| Jan | -5.1 | -5.8 (0.1)a | -5.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| AE ∆% Jan | -46.6 | -51.2 (3.7)a | -51.8 | 6.2 | 4.9 |

| 2012 | |||||

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2012*** | 9.0 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 2.3 |

| Dec | 2.8 | 2.8 (0.3)* | 2.8 (0.5)* | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Nov | 1.4 | 1.3 (0.6)* | 1.4 (0.9)* | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| AE ∆% Nov-Dec | 28.3 | 27.5 (5.5)* | 28.3 (8.7)* | 2.4 | 3.0 |

| Oct | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | -0.1 |

| Sep | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Aug | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| AE ∆% Aug-Oct | 7.9 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| Jul | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Jun | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| May | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Apr | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| AE ∆% Apr-Jul | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Mar | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.1 |

| Feb | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Mar | 9.6 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 3.7 |

| 2011 | |||||

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2011* | 5.1 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 1.8 |

| Dec | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nov | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| Oct | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Sep | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| AE ∆% Sep-Dec | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Aug | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.2 | -0.1 |

| Jul | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Jun | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| May | 0.3 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.3 | -0.1 |

| AE ∆% May-Aug | 4.9 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 0.9 |

| Apr | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Mar | 0.3 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Feb | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Jan | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 8.1 | 5.2 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 1.5 |

| 2010 | |||||

| ∆% Jan-Dec 2010** | 4.9 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 4.4 | 2.9 |

| Dec | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Nov | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Oct | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| IVQ2010∆% | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| IVQ2010 AE ∆% | 7.9 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 4.1 |

Notes: *Excluding exceptional income gains in Nov and Dec 2012 because of anticipated tax increases in Jan 2013 ((page 2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1212.pdf). a Excluding employee contributions for government social insurance (pages 1-2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0113.pdf )Excluding NPI: current dollars personal income; NDPI: current dollars disposable personal income; RDPI: chained (2005) dollars DPI; NPCE: current dollars personal consumption expenditures; RPCE: chained (2005) dollars PCE; AE: annual equivalent; IVQ2010: fourth quarter 2010; A: annual equivalent

Percentage change month to month seasonally adjusted

*∆% Dec 2011/Dec 2010 **∆% Dec 2010/Dec 2009 *** ∆% Dec 2012/Dec 2011

Source: US Bureau of Economic http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The rates of growth of real disposable income decline in the final quarter of 2013 because of the increases in the last two months of 2012 in anticipation of the tax increases of the “fiscal cliff” episode. The increase was provided in the “fiscal cliff” law H.R. 8 American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-112hr8eas/pdf/BILLS-112hr8eas.pdf).

The 12-month rate of increase of real disposable income fell to 0.0 percent in Oct 2013 and minus 1.3 percent in Nov 2013 partly because of the much higher level in late 2012 in anticipation of incomes to avoid increases in taxes in 2013. Real disposable income fell 4.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2013 primarily because of the much higher level in late 2012 in anticipation of income to avoid increases in taxes in 2013. Real disposable income increased 2.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan 2014, partly because of the low level in Jan 2013 after anticipation of incomes in late 2012 in avoiding the fiscal cliff episode. Real disposable income increased 2.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Sep 2014.

RPCE growth decelerated less sharply from close to 3 percent in IVQ 2010 to 2.1 percent in Sep 2014. Subdued growth of RPCE could affect revenues of business. Growth rates of personal consumption have weakened. Goods and especially durable goods have been driving growth of PCE as shown by the much higher 12-month rates of growth of real goods PCE (RPCEG) and durable goods real PCE (RPCEGD) than services real PCE (RPCES). Growth of consumption of goods and, in particular, of consumer durable goods drives the faster expansion of the economy while growth of consumption of services is much more moderate. The 12-month rates of growth of RPCEGD have fallen from around 10 percent and even higher in several months from Sep 2010 to Feb 2011 to the range of 2.0 to 8.3 percent from Jan to Sep 2014. RPCEG growth rates have fallen from around 5 percent late in 2010 and early Jan-Feb 2011 to the range of 1.2 to 4.1 percent from Jan to Sep 2014. In Sep 2014, RPCEG increased 2.8 percent in 12 months and RPCEGD 7.1 percent while RPCES increased only 1.7 percent. There are limits to sustained growth based on financial repression in an environment of weak labor markets and real labor remuneration.

Table IB-2, Real Disposable Personal Income and Real Personal Consumption Expenditures

Percentage Change from the Same Month a Year Earlier %

| RDPI | RPCE | RPCEG | RPCEGD | RPCES | |

| 2014 | |||||

| Sep | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 1.7 |

| Aug | 2.7 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 8.3 | 1.9 |

| Jul | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 1.7 |

| Jun | 2.5 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 7.0 | 1.8 |

| May | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 1.9 |

| Apr | 2.5 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 1.7 |

| Mar | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 1.9 |

| Feb | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 2.0 |

| Jan | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| 2013 | |||||

| Dec | -4.2 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 2.4 |

| Nov | -1.3 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

| Oct | 0.0 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 7.4 | 2.2 |

| Sep | 0.9 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 1.9 |

| Aug | 1.1 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 2.0 |

| Jul | 0.6 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 7.5 | 1.5 |

| Jun | 0.4 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 8.1 | 1.8 |

| May | 0.4 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 1.7 |

| Apr | 0.0 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 6.8 | 1.8 |

| Mar | 0.0 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 1.9 |

| Feb | -0.2 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 1.4 |

| Jan | -0.1 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 8.0 | 1.5 |

| 2012 | |||||

| Dec | 7.0 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 1.6 |

| Nov | 4.8 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 8.2 | 1.5 |

| Oct | 3.2 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 5.4 | 1.3 |

| Sep | 2.7 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 8.5 | 1.1 |

| Aug | 1.9 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 0.9 |

| Jul | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 7.3 | 1.3 |

| Jun | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 8.4 | 1.2 |

| May | 3.0 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 7.6 | 1.3 |

| Apr | 2.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 6.5 | 1.5 |

| Mar | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 5.8 | 1.2 |

| Feb | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 6.9 | 1.7 |

| Jan | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 5.8 | 1.4 |

| Dec 2011 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.1 |

| Dec 2010 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 8.4 | 2.1 |

Notes: RDPI: real disposable personal income; RPCE: real personal consumption expenditures (PCE); RPCEG: real PCE goods; RPCEGD: RPCEG durable goods; RPCES: RPCE services

Numbers are percentage changes from the same month a year earlier

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-1 shows US real personal consumption expenditures (RPCE) between 1999 and 2014. There is an evident drop in RPCE during the global recession in 2007 to 2009 but the slope is flatter during the current recovery than in the period before 2007.

Chart IB-1, US, Real Personal Consumption Expenditures, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates 1999-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Percent changes from the prior period in seasonally adjusted annual equivalent quarterly rates (SAAR) of real personal consumption expenditures (RPCE) are provided in Chart IB-2 from 1995 to 2014. The average rate could be visualized as a horizontal line. Although there are not yet sufficient observations, it appears from Chart IB-2 that the average rate of growth of RPCE was higher before the recession than during the past twenty quarters of expansion that began in IIIQ2009.

Chart IB-2, Percent Change from Prior Period in Real Personal Consumption Expenditures, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates 1995-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Personal income and its disposition are shown in Table IB-3. The latest estimates and revisions have changed movements in five forms. (1) Increase in Sep 2014 of personal income by $22.7 billion or 0.2 percent and increase of disposable income of $15.7 billion or 0.1 percent with increase of wages and salaries of 0.2 percent. (2) Decrease of personal income of $302.9 billion from Dec 2012 to Dec 2013 or by 2.1 percent and decrease of disposable income of $397.7 billion or by 3.1 percent. Wages and salaries increased $30.8 billion from Dec 2012 to Dec 2013 or by 0.4 percent. Large part of these declines occurred because of the comparison of high levels in late 2012 in anticipation of tax increases in 2013. In 2012, personal income increased $1203.0 billion or 9.0 percent while wages and salaries increased 7.5 percent and disposable income 8.6 percent. Significant part of these gains occurred in Dec 2012 in anticipation of incomes because of tax increases beginning in Jan 2013. (3) Increase of $651.3 billion of personal income in 2011 or by 5.1 percent with increase of salaries of 2.7 percent and disposable income of 4.1 percent. (4) Increase of the rate of savings as percent of disposable income from 5.9 percent in Dec 2010 to 6.4 percent in Dec 2011, decreasing to 4.1 percent in Dec 2013. (5) Increase of personal income of $587.8 billion or 4.1 percent from Sep 2013 to Sep 2014. Nominal disposable income increased $497.9 billion or 3.9 percent while salaries and wages increased $366.9 billion or 5.1 percent.

Table IB-3, US, Personal Income and its Disposition, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates USD Billions

| Personal | Wages & | Personal | DPI | Savings | |

| Sep 2014 | 14,892.6 | 7,540.9 | 1,785.5 | 13,134.1 | 5.6 |

| Aug 2014 | 14,869.9 | 7,527.0 | 1,751.5 | 13,118.4 | 5.4 |

| Change Sep 2014/ Aug 2014 | 22.7 ∆% 0.2 | 13.9 ∆% 0.2 | 34.0 ∆% 1.9 | 15.7 ∆% 0.1 | |

| Sep 2013 | 14,304.8 | 7,174.0 | 1,668.6 | 12,636.2 | 5.2 |

| Change Sep 2014/Sep 2013 | 587.8 ∆% 4.1 | 366.9 ∆% 5.1 | 116.9 ∆% 7.0 | 497.9 ∆% 3.9 | |

| Dec 2013 | 14,320.0 | 7,214.1 | 1,695.3 | 12,624.8 | 4.1 |

| Dec 2012 | 14,622.9 | 7,183.3 | 1,600.4 | 13,022.5 | 10.5 |

| Change Dec 2013/ Dec 2012 | -302.9 ∆% -2.1 | 30.8 ∆% 0.4 | 94.9 ∆% 5.9 | -397.7 ∆% -3.1 | |

| Change Dec 2012/ Dec 2011 | 1203.0 ∆% 9.0 | 500.4 ∆% 7.5 | 169.1 ∆% 11.8 | 1033.9 ∆% 8.6 | |

| Dec 2011 | 13,419.9 | 6,682.9 | 1,431.3 | 11,988.6 | 6.4 |

| Dec 2010 | 12,768.6 | 6,506.0 | 1,254.2 | 11,514.5 | 5.9 |

| Change Dec 2011/ Dec 2010 | 651.3 ∆% 5.1 | 176.9 ∆% 2.7 | 177.1 ∆% 14.1 | 474.1 ∆% 4.1 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides a wealth of revisions and enhancements of US personal income and outlays since 1929 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Table IB-4 provides growth rates of real disposable income and real disposable income per capita in the long-term and selected periods. Real disposable income consists of after-tax income adjusted for inflation. Real disposable income per capita is income per person after taxes and inflation. There is remarkable long-term trend of real disposable income of 3.2 percent per year on average from 1929 to 2013 and 2.0 percent in real disposable income per capita. Real disposable income increased at the average yearly rate of 3.7 percent from 1947 to 1999 and real disposable income per capita at 2.3 percent. These rates of increase broadly accompany rates of growth of GDP. Institutional arrangements in the United States provided the environment for growth of output and income after taxes, inflation and population growth. There is significant break of growth by much lower 2.3 percent for real disposable income on average from 1999 to 2013 and 1.4 percent in real disposable per capita income. Real disposable income grew at 3.5 percent from 1980 to 1989 and real disposable per capita income at 2.6 percent. In contrast, real disposable income grew at only 1.4 percent on average from 2006 to 2013 and real disposable income per capita at 0.5 percent. The United States has interrupted its long-term and cyclical dynamism of output, income and employment growth. Recovery of this dynamism could prove to be a major challenge. Cyclical uncommonly slow growth explains weakness in the current whole cycle instead of the allegation of secular stagnation.

Table IB-4, Average Annual Growth Rates of Real Disposable Income (RDPI) and Real Disposable Income per Capita (RDPIPC), Percent per Year

| RDPI Average ∆% | |

| 1929-2013 | 3.2 |

| 1947-1999 | 3.7 |

| 1999-2013 | 2.3 |

| 1999-2006 | 3.2 |

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 |

| 2006-2013 | 1.4 |

| RDPIPC Average ∆% | |

| 1929-2013 | 2.0 |

| 1947-1999 | 2.3 |

| 1999-2013 | 1.4 |

| 1999-2006 | 2.2 |

| 1980-1989 | 2.6 |

| 2006-2013 | 0.5 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

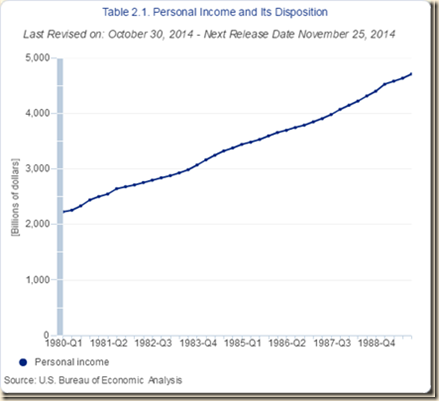

Chart IB-3 provides personal income in the US between 1980 and 1989. These data are not adjusted for inflation that was still high in the 1980s in the exit from the Great Inflation of the 1960s and 1970s. Personal income grew steadily during the 1980s after recovery from two recessions from Jan IQ1980 to Jul IIIQ1980 and from Jul IIIQ1981 to Nov IVQ1982.

Chart IB-3, US, Personal Income, Billion Dollars, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

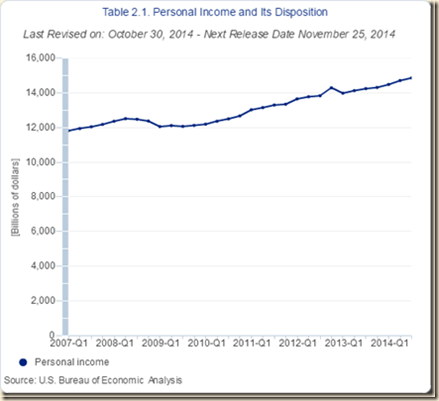

A different evolution of personal income is shown in Chart IB-4. Personal income also fell during the recession from Dec IVQ2007 to Jun IIQ2009 (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). Growth of personal income during the expansion has been tepid even with the new revisions. In IVQ2012, nominal disposable personal income grew at the SAAR of 13.8 percent and real disposable personal income at 11.8 percent (Table 2.1 http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The BEA explains as follows: “Personal income in November and December was boosted by accelerated and special dividend payments to persons and by accelerated bonus payments and other irregular pay in private wages and salaries in anticipation of changes in individual income tax rates. Personal income in December was also boosted by lump-sum social security benefit payments” (page 2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1212.pdf pages 1-2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0113.pdf). The Bureau of Economic Analysis explains as (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0213.pdf 2-3): “The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance reflected the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday,” that increased the social security contribution rate for employees and self-employed workers by 2.0 percentage points, or $114.1 billion at an annual rate. For additional information, see FAQ on “How did the expiration of the payroll tax holiday affect personal income for January 2013?” at www.bea.gov. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance also reflected an increase in the monthly premiums paid by participants in the supplementary medical insurance program, in the hospital insurance provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and in the social security taxable wage base.”

The increase was provided in the “fiscal cliff” law H.R. 8 American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-112hr8eas/pdf/BILLS-112hr8eas.pdf).

In IQ2013, personal income fell at the SAAR of minus 8.6 percent; real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at minus 11.9 percent; and real disposable personal income at minus 12.6 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0814.pdf). The BEA explains as follows (page 3 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0313.pdf):

“The February and January changes in disposable personal income (DPI) mainly reflected the effect of special factors in January, such as the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday” and the acceleration of bonuses and personal dividends to November and to December in anticipation of changes in individual tax rates.”

In IIQ2013, personal income grew at 4.5 percent, real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at 4.6 percent and real disposable income at 3.8 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIIQ2013, personal income grew at 3.3 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 1.5 percent and real disposable income at 2.0 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IVQ2013, personal income grew at 1.8 percent and real disposable income at 0.2 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0814.pdf). In IQ2014, personal income grew at 4.9 percent in nominal terms and 3.2 percent in real terms excluding current transfer receipts while nominal disposable income grew at 4.8 percent and real disposable income at 3.4 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIQ2014, personal income grew at 6.3 percent and 3.8 percent in real terms excluding current transfers. Nominal disposable income grew at 6.8 percent and at 4.4 percent in real terms (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIIQ2014, personal income grew at 4.2 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 2.3 percent and real disposable personal income at 2.7 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf).

Chart IB-4, US, Personal Income, Current Billions of Dollars, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Real or inflation-adjusted disposable personal income is provided in Chart IB-5 from 1980 to 1989. Real disposable income after allowing for taxes and inflation grew steadily at high rates during the entire decade.

Chart IB-5, US, Real Disposable Income, Billions of Chained 2009 Dollars, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

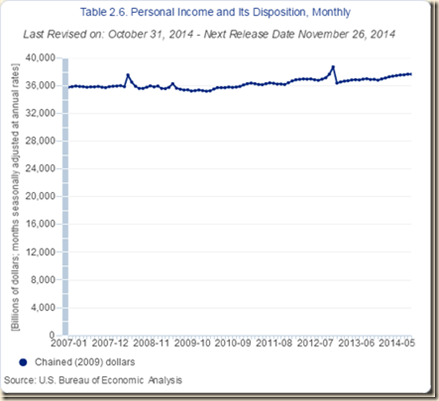

Chart IB-6 provides real disposable income from 2007 to 2014. In IQ2013, personal income fell at the SAAR of minus 8.6 percent; real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at minus 11.9 percent; and real disposable personal income at minus 12.6 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0814.pdf). The BEA explains as follows (page 3 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0313.pdf):

“The February and January changes in disposable personal income (DPI) mainly reflected the effect of special factors in January, such as the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday” and the acceleration of bonuses and personal dividends to November and to December in anticipation of changes in individual tax rates.”

In IIQ2013, personal income grew at 4.5 percent, real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at 4.6 percent and real disposable income at 3.8 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIIQ2013, personal income grew at 3.3 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 1.5 percent and real disposable income at 2.0 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IVQ2013, personal income grew at 1.8 percent and real disposable income at 0.2 percent (Table 6 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0814.pdf). In IQ2014, personal income grew at 4.9 percent in nominal terms and 3.2 percent in real terms excluding current transfer receipts while nominal disposable income grew at 4.8 percent and real disposable income at 3.4 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIQ2014, personal income grew at 6.3 percent and 3.8 percent in real terms excluding current transfers. Nominal disposable income grew at 6.8 percent and at 4.4 percent in real terms (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf). In IIIQ2014, personal income grew at 4.2 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 2.3 percent and real disposable personal income at 2.7 percent (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0914.pdf).

Chart IB-6, US, Real Disposable Income, Billions of Chained 2009 Dollars, Quarterly Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, 2007-2014

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-7 provides percentage quarterly changes in real disposable income from the preceding period at seasonally adjusted annual rates from 1980 to 1989. Rates of changes were high during the decade with few negative changes.

Chart IB-7, US, Real Disposable Income Percentage Change from Preceding Period at Quarterly Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rates, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-8 provides percentage quarterly changes in real disposable income from the preceding period at seasonally adjusted annual rates from 2007 to 2013. There has been a period of positive rates followed by decline of rates and then negative and low rates in 2011. Recovery in 2012 has not reproduced the dynamism of the brief early phase of expansion. In IVQ2012, nominal disposable personal income grew at the SAAR of 13.8 percent and real disposable personal income at 11.8 percent (Table 2.1 http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The BEA explains as: “Personal income in November and December was boosted by accelerated and special dividend payments to persons and by accelerated bonus payments and other irregular pay in private wages and salaries in anticipation of changes in individual income tax rates. Personal income in December was also boosted by lump-sum social security benefit payments” (page 2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1212.pdf). The BEA explains as follows (page 3 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0313.pdf):

“The February and January changes in disposable personal income (DPI) mainly reflected the effect of special factors in January, such as the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday” and the acceleration of bonuses and personal dividends to November and to December in anticipation of changes in individual tax rates.”

Personal income fell at 8.6 percent in IQ2013; nominal disposable personal income fell at 11.7 percent and real disposable income fell at 12.6 percent. In IIQ2013, personal income increased at 4.5 percent, real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at 4.6 percent and real disposable income at 3.8 percent. In IIIQ2013, personal income increased at 3.3 percent, real personal income excluding current transfer receipts at 1.5 percent and real disposable income at 2.0 percent. In IVQ2013, nominal personal income increased at 1.8 percent, nominal disposable income at 1.2 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 1.0 percent and real disposable income at 0.2 percent. In IQ2014, nominal personal income grew at 4.9 percent, nominal disposable income at 4.8 percent, real personal income excluding current transfers at 3.2 percent and real disposable personal income at 3.4 percent. In IIQ2014, nominal personal income grew at 6.3 percent and 3.8 percent in real terms excluding current transfers while nominal disposable income grew at 6.8 percent and at 4.4 percent in real terms. In IIIQ2014, nominal personal income grew at 4.2 percent and 2.3 percent in real terms excluding current transfers while nominal disposable income grew at 4.0 percent and 2.7 percent in real terms.

Chart, IB-8, US, Real Disposable Income, Percentage Change from Preceding Period at Seasonally-Adjusted Annual Rates, 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

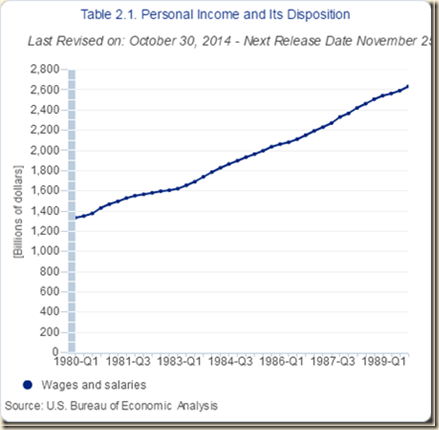

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates US personal income in Sep 2014 at the seasonally adjusted annual rate of $14,892,6 billion, as shown in Table IB-3 above (see Table 1 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2014/pdf/pi0714.pdf). The major portion of personal income is compensation of employees of $9,329.3 billion, or 62.6 percent of the total. Wages and salaries are $7,540.9 billion, of which $6,316.6 billion by private industries and supplements to wages and salaries of $1,788.4 billion (contributions to social insurance are $554.2 billion). In Feb 1988 (at the comparable month after the end of the 20th quarter of cyclical expansion), US personal income was $4,125.5 billion at SAAR (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). Compensation of employees was $2,862.4 billion, or 69.4 percent of the total. Wages and salaries were $2,368.6 billion of which $1925.7 billion by private industries. Supplements to wages and salaries were $493.7 billion with employer contributions to pension and insurance funds of $314.0 billion and $179.7 billion to government social insurance. Chart IB-9 provides US wages and salaries by private industries in the 1980s. Growth was robust after the interruption of the recessions.

Chart IB-9, US, Wages and Salaries, Private Industries, Quarterly, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates Billions of Dollars, 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

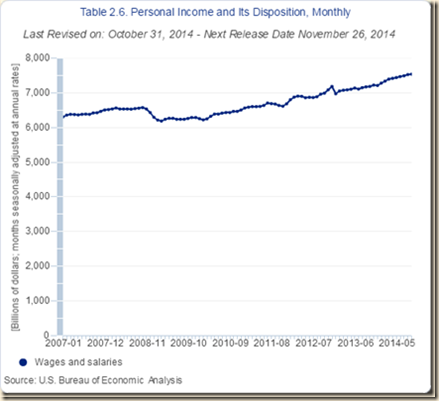

Chart IB-10 shows US wages and salaries of private industries from 2007 to 2014. There is a drop during the contraction followed by initial recovery in 2010 and then the current much weaker relative performance in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.

Chart IB-10, US, Wage and Salary Disbursement, Private Industries, Quarterly, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, Billions of Dollars 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-11 provides finer detail with monthly wages and salaries of private industries from 2007 to 2014. Anticipations of income in late 2012 to avoid tax increases in 2013 cloud comparisons.

Chart IB-11, US, Wages and Salaries, Private Industries, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, Billions of Dollars 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-12 provides monthly real disposable personal income per capita from 1980 to 1989. This is the ultimate measure of wellbeing in receiving income by obtaining the value per inhabitant. The measure cannot adjust for the distribution of income. Real disposable personal income per capita grew rapidly during the expansion after 1983 and continued growing during the rest of the decade.

Chart IB-12, US, Real Disposable Per Capita Income, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, Chained 2009 Dollars 1980-1989

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IB-5 provides the comparison between the cycle of the 1980s and the current cycle. Real per capita disposable income (RDPI-PC) increased 21.6 percent from Dec 1979 to Mar 1988. In the comparable period in the actual cycle, real per capital disposable income increased 5.1 percent.

Table IB-5, Percentage Changes of Real Disposable Personal Income Per Capita

| Month | RDPI-PC ∆% 12/79 | RDPI-PC ∆% YOY | Month | RDPI-PC ∆% 12/07 | RDPI-PC ∆% YOY |

| 11/1982 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 6/2009 | -0.6 | -2.4 |

| 12/1982 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 9/2009 | -1.3 | -0.6 |

| 12/1983 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 6/2010 | -0.4 | 0.2 |

| 12/1987 | 20.4 | 2.7 | 6/2014 | 4.7 | 1.8 |

| 1/1988 | 20.6 | 2.6 | 7/2014 | 4.8 | 2.0 |

| 2/1988 | 21.2 | 2.6 | 8/2014 | 5.1 | 2.0 |

| 3/1988 | 21.6 | 2.9 | 9/2014 | 5.1 | 1.8 |

RDPI: Real Disposable Personal Income; RDPI-PC, Real Disposable Personal Income Per Capita

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

National Bureau of Economic Research

http://www.nber.org/cycles.html

Chart IB-13 provides monthly real disposable personal income per capita from 2007 to 2014. There was initial recovery from the drop during the global recession followed by stagnation.

Chart IB-13, US, Real Disposable Per Capita Income, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted at Annual Rates, Chained 2009 Dollars 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IB-6 provides data for analysis of the current cycle. Real disposable income (RDPI) increased 10.7 percent from Dec 2007 to Sep 2014 (column RDPI ∆% 12/07). In the same period, real disposable income per capita increased 5.1 percent (column RDPI-PC ∆% 12/07). The annual equivalent rate of increase of real disposable income per capita is 0.7 percent, only a fraction of 2.0 percent on average from 1929 to 2013, and 1.8 percent for real disposable income, much lower than 3.2 percent on average from 1929 to 2013.

Table IB-6, Percentage Changes of Real Disposable Personal Income and Real Disposable Personal Income Per Capita

| Month | RDPI | RDPI ∆% Month | RDPI ∆% YOY | RDPI-PC ∆% 12/07 | RDPI-PC ∆% Month | RDPI-PC ∆% YOY |

| 6/09 | 0.8 | -1.7 | -1.5 | -0.6 | -1.8 | -2.4 |

| 9/09 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -1.3 | 0.1 | -0.6 |

| 6/10 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | -0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 12/10 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 2.1 |

| 6/11 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| 12/11 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| 6/12 | 6.9 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| 10/12 | 7.7 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 0.5 | 2.5 |

| 11/12 | 9.2 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 4.1 |

| 12/12 | 12.3 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 2.8 | 6.2 |

| 6/13 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 0.1 | -0.3 |

| 12/13 | 7.6 | -0.2 | -4.2 | 2.7 | -0.3 | -4.9 |

| 1/14 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| 2/14 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| 3/14 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 1.7 |

| 4/14 | 9.5 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| 5/14 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| 6/14 | 10.1 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.7 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| 7/14 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 8/14 | 10.6 | 0.3 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| 9/14 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 1.8 |

RDPI: Real Disposable Personal Income; RDPI-PC, Real Disposable Personal Income Per Capita

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

National Bureau of Economic Research

http://www.nber.org/cycles.html

IA2 Financial Repression. McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1974) argue that legal restrictions on financial institutions can be detrimental to economic development. “Financial repression” is the term used in the economic literature for these restrictions (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 81-6; for historical analysis see Pelaez 1975). Excessive official regulation frustrates financial development required for growth (Haber 2011). Emphasis on disclosure can reduce bank fragility and corruption, empowering investors to enforce sound governance (Barth, Caprio and Levine 2006). Interest rate ceilings on deposits and loans have been commonly used. The Banking Act of 1933 imposed prohibition of payment of interest on demand deposits and ceilings on interest rates on time deposits. These measures were justified by arguments that the banking panic of the 1930s was caused by competitive rates on bank deposits that led banks to engage in high-risk loans (Friedman, 1970, 18; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 74-5). The objective of policy was to prevent unsound loans in banks. Savings and loan institutions complained of unfair competition from commercial banks that led to continuing controls with the objective of directing savings toward residential construction. Friedman (1970, 15) argues that controls were passive during periods when rates implied on demand deposit were zero or lower and when Regulation Q ceilings on time deposits were above market rates on time deposits. The Great Inflation or stagflation of the 1960s and 1970s changed the relevance of Regulation Q.

Most regulatory actions trigger compensatory measures by the private sector that result in outcomes that are different from those intended by regulation (Kydland and Prescott 1977). Banks offered services to their customers and loans at rates lower than market rates to compensate for the prohibition to pay interest on demand deposits (Friedman 1970, 24). The prohibition of interest on demand deposits was eventually lifted in recent times. In the second half of the 1960s, already in the beginning of the Great Inflation (DeLong 1997), market rates rose above the ceilings of Regulation Q because of higher inflation. Nobody desires savings allocated to time or savings deposits that pay less than expected inflation. This is a fact currently with zero interest rates and consumer price inflation of 1.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Mar 2013 (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/) but rising during waves of carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures exposures (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/09/world-inflation-waves-squeeze-of.html). Funding problems motivated compensatory measures by banks. Money-center banks developed the large certificate of deposit (CD) to accommodate increasing volumes of loan demand by customers. As Friedman (1970, 25) finds:

“Large negotiable CD’s were particularly hard hit by the interest rate ceiling because they are deposits of financially sophisticated individuals and institutions who have many alternatives. As already noted, they declined from a peak of $24 billion in mid-December, 1968, to less than $12 billion in early October, 1969.”

Banks created different liabilities to compensate for the decline in CDs. As Friedman (1970, 25; 1969) explains:

“The most important single replacement was almost surely ‘liabilities of US banks to foreign branches.’ Prevented from paying a market interest rate on liabilities of home offices in the United States (except to foreign official institutions that are exempt from Regulation Q), the major US banks discovered that they could do so by using the Euro-dollar market. Their European branches could accept time deposits, either on book account or as negotiable CD’s at whatever rate was required to attract them and match them on the asset side of their balance sheet with ‘due from head office.’ The head office could substitute the liability ‘due to foreign branches’ for the liability ‘due on CDs.”

Friedman (1970, 26-7) predicted the future:

“The banks have been forced into costly structural readjustments, the European banking system has been given an unnecessary competitive advantage, and London has been artificially strengthened as a financial center at the expense of New York.”

In short, Depression regulation exported the US financial system to London and offshore centers. What is vividly relevant currently from this experience is the argument by Friedman (1970, 27) that the controls affected the most people with lower incomes and wealth who were forced into accepting controlled-rates on their savings that were lower than those that would be obtained under freer markets. As Friedman (1970, 27) argues:

“These are the people who have the fewest alternative ways to invest their limited assets and are least sophisticated about the alternatives.”

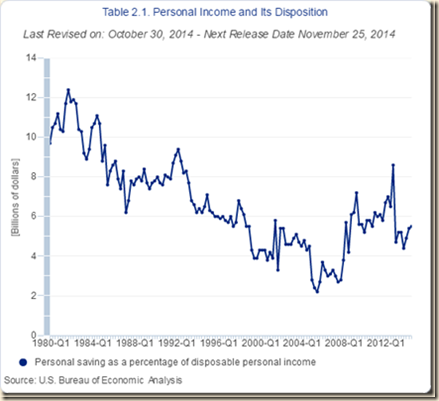

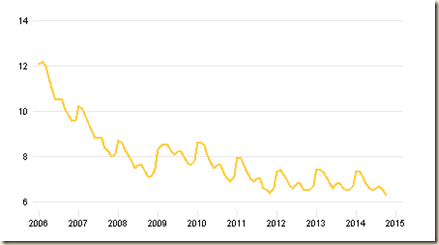

Chart IB-14 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) provides quarterly savings as percent of disposable income or the US savings rate from 1980 to 2014. There was a long-term downward sloping trend from 12 percent in the early 1980s to 2.0 percent in Jul 2005. The savings rate then rose during the contraction and in the expansion. In 2011 and into 2012 the savings rate declined as consumption is financed with savings in part because of the disincentive or frustration of receiving a few pennies for every $10,000 of deposits in a bank. The savings rate increased in the final segment of Chart IB-14 in 2012 followed by another decline because of the pain of the opportunity cost of zero remuneration for hard-earned savings.

Chart IB-14, US, Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Personal Income, Quarterly, 1980-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Chart IB-14A provides the US personal savings rate, or personal savings as percent of disposable personal income, on an annual basis from 1929 to 2013. The US savings rate shows decline from around 10 percent in the 1960s to around 5 percent currently.

Chart IB-14A, US, Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Personal Income, Annual, 1929-2013

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IB-7 provides personal savings as percent of disposable income and annual change of real disposable personal income in selected years since 1930. Savings fell from 4.4 percent of disposable personal income in 1930 to minus 0.8 percent in 1933 while real disposable income contracted 5.3 percent in 1930 and 2.9 percent in 1933. Savings as percent of disposable personal income swelled during World War II to 27.9 percent in 1944 with increase of real disposable income of 3.1 percent. Savings as percent of personal disposable income fell steadily over decades from 11.5 percent in 1982 to 2.5 percent in 2005. Savings as percent of disposable personal income was 4.9 percent in 2013 while real disposable income fell 0.2 percent. The average ratio of savings as percent of disposable income fell from 9.3 percent from 1980 to 1989 to 5.4 percent on average from 2007 to 2013. Real disposable income grew on average at 3.5 percent from 1980 to 1989 and at 1.2 percent on average from 2007 to 2013.

Table IB-7, US, Personal Savings as Percent of Disposable Personal Income, Annual, Selected Years 1929-1913

| Personal Savings as Percent of Disposable Personal Income | Annual Change of Real Disposable Personal Income | |

| 1930 | 4.4 | -5.3 |

| 1933 | -0.8 | -2.9 |

| 1944 | 27.9 | 3.1 |

| 1947 | 6.3 | -4.1 |

| 1954 | 10.3 | 1.4 |

| 1958 | 11.4 | 1.1 |

| 1960 | 10.0 | 2.6 |

| 1970 | 12.6 | 4.6 |

| 1975 | 13.0 | 2.5 |

| 1982 | 11.5 | 2.1 |

| 1989 | 7.8 | 3.0 |

| 1992 | 8.9 | 4.3 |

| 2002 | 5.0 | 3.1 |

| 2003 | 4.8 | 2.7 |

| 2004 | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| 2005 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| 2006 | 3.3 | 4.0 |

| 2007 | 3.0 | 2.1 |

| 2008 | 4.9 | 1.5 |

| 2009 | 6.1 | -0.4 |

| 2010 | 5.6 | 1.0 |

| 2011 | 6.0 | 2.5 |

| 2012 | 7.2 | 3.0 |

| 2013 | 4.9 | -0.2 |

| Average Savings Ratio | ||

| 1980-1989 | 9.3 | |

| 2007-2013 | 5.4 | |

| Average Yearly ∆% Real Disposable Income | ||

| 1980-1989 | 3.5 | |

| 2007-2013 | 1.2 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

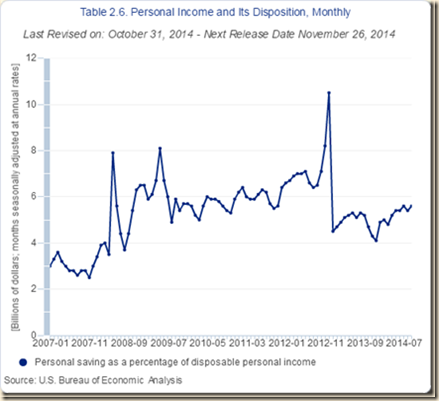

Chart IB-15 of the US Bureau of Economic Analysis provides personal savings as percent of personal disposable income, or savings ratio, from Jan 2007 to Sep 2014. The uncertainties caused by the global recession resulted in sharp increase in the savings ratio that peaked at 7.9 percent in May 2008 (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm). The second peak occurred at 8.1 percent in May 2009. There was another rising trend until 5.9 percent in Jun 2010 and then steady downward trend until 5.3 percent in Nov 2011. This was followed by an upward trend with 7.1 percent in Jun 2012 but decline to 6.4 percent in Aug 2012 followed by jump to 10.5 percent in Dec 2012. Swelling realization of income in Oct-Dec 2012 in anticipation of tax increases in Jan 2013 caused the jump of the savings rate to 10.5 percent in Dec 2012. The BEA explains as: Personal income in November and December was boosted by accelerated and special dividend payments to persons and by accelerated bonus payments and other irregular pay in private wages and salaries in anticipation of changes in individual income tax rates. Personal income in December was also boosted by lump-sum social security benefit payments” (page 2 at http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1212.pdf). There was a reverse effect in Jan 2013 with decline of the savings rate to 3.6 percent. Real disposable personal income fell 5.1 percent and real disposable per capita income fell from $38,175 in Dec 2012 to $36,195 in Jan 2013 or by 5.2 percent, which is explained by the Bureau of Economic Analysis as follows (page 3 http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi0213.pdf):

“Contributions for government social insurance -- a subtraction in calculating personal income --increased $6.4 billion in February, compared with an increase of $126.8 billion in January. The

January estimate reflected increases in both employer and employee contributions for government social insurance. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance reflected the expiration of the “payroll tax holiday,” that increased the social security contribution rate for employees and self-employed workers by 2.0 percentage points, or $114.1 billion at an annual rate. For additional information, see FAQ on “How did the expiration of the payroll tax holiday affect personal income for January 2013?” at www.bea.gov. The January estimate of employee contributions for government social insurance also reflected an increase in the monthly premiums paid by participants in the supplementary medical insurance program, in the hospital insurance provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and in the social security taxable wage base; together, these changes added $12.9 billion to January. Employer contributions were boosted $5.9 billion in January, which reflected increases in the social security taxable wage base (from $110,100 to $113,700), in the tax rates paid by employers to state unemployment insurance, and in employer contributions for the federal unemployment tax and for pension guaranty. The total contribution of special factors to the January change in contributions for government social insurance was $132.9 billion.”

Chart IB-15, US, Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Income, Monthly 2007-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Table IB-8 provides personal saving as percent of disposable income, change of real disposable income relative to Dec 2007 (RDPI ∆% 12/07), monthly percentage change of real disposable income (RDPI ∆% Month) and percentage of real disposable income in a month relative to the same month a year earlier (RDPI ∆% YOY). The ratio of personal saving to disposable income eased to 5.6 percent in Sep 2014 with cumulative growth of real disposable income of 10.7 percent since Dec 2007 at the rate of 1.5 percent in annual equivalent that is much lower than 3.2 percent over the long-term from 1929 to 2013.

Table IB-8, US, Savings Ratio and Real Disposable Income, % and ∆%

| Personal Income as % Disposable Income | RDPI ∆% 12/07 | RDPI ∆% Month | RDPI ∆% YOY | |

| May 2008 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 5.7 |

| May 2009 | 8.1 | 2.5 | 1.6 | -2.5 |

| Jun 2010 | 5.9 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Nov 2011 | 5.6 | 4.2 | -0.1 | 1.5 |

| Jun 2012 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| Aug 2012 | 6.4 | 6.5 | -0.2 | 1.9 |

| Dec 2012 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 2.8 | 7.0 |

| Jan 2013 | 4.5 | 5.6 | -5.9 | -0.1 |

| Feb 2013 | 4.7 | 6.2 | 0.5 | -0.2 |

| Mar 2013 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Apr 2013 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| May 2013 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Jun 2013 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Jul 2013 | 5.1 | 7.3 | -0.1 | 0.6 |

| Aug 2013 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 |

| Sep 2013 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Oct 2013 | 4.7 | 7.7 | -0.3 | 0.0 |

| Nov 2013 | 4.3 | 7.8 | 0.1 | -1.3 |

| Dec 2013 | 4.1 | 7.6 | -0.2 | -4.2 |

| Jan 2014 | 4.9 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Feb 2014 | 5.0 | 8.6 | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Mar 2014 | 4.8 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| Apr 2014 | 5.2 | 9.5 | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| May 2014 | 5.4 | 9.8 | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Jun 2014 | 5.4 | 10.1 | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| Jul 2014 | 5.6 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| Aug 2014 | 5.4 | 10.6 | 0.3 | 2.7 |

| Sep 2014 | 5.6 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 2.5 |

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

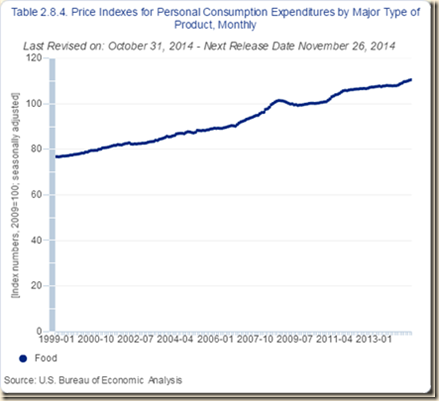

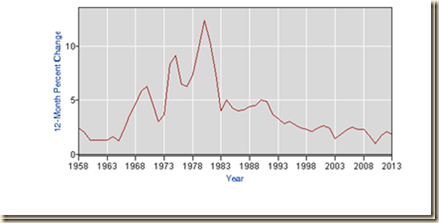

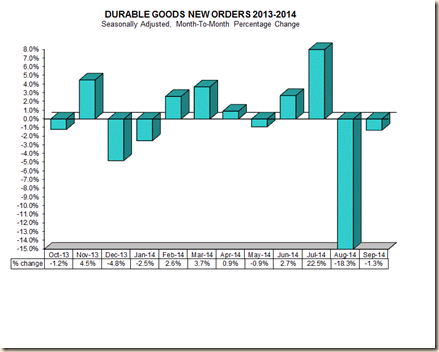

The revisions and enhancements of United States GDP and personal income accounts by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) (http://bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm) also provide critical information in assessing indexes of prices of personal consumption. There are waves of inflation similar to those worldwide (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2014/10/financial-oscillations-world-inflation.html) in inflation of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) in Table IV-5. These waves are in part determined by commodity price shocks originating in the carry trade from zero interest rates to positions in risk financial assets, in particular in commodity futures, which increase the prices of food and energy when there is relaxed risk aversion. Return of risk aversion causes collapse in prices. Resulting fluctuations of prices confuse risk/return decisions, inducing financial instability with adverse financial and economic consequences. The first wave is in Jan-Apr 2011 when headline PCE inflation increased at the average annual equivalent rate of 4.0 percent and PCE inflation excluding food and energy (PCEX) at 1.8 percent. The drivers of inflation were increases in food prices (PCEF) at the annual equivalent rate of 7.8 percent and of energy prices (PCEE) at 30.1 percent. This behavior will prevail under zero interest rates and relaxed risk aversion because of carry trades from zero interest rates to leveraged positions in commodity futures. The second wave occurred in May-Jun 2011 when risk aversion from the European sovereign risk crisis interrupted the carry trade. PCE prices increased 1.8 percent in annual equivalent and 1.8 percent excluding food and energy. The third wave is captured by the annual equivalent rates in Jul-Sep 2011 of headline PCE inflation of 2.4 percent with subdued PCE inflation excluding food and energy of 2.0 percent while PCE food rose at 6.2 percent and PCE energy increased at 5.3 percent. In the fourth wave in Oct-Dec 2011, increased risk aversion explains the fall of the annual equivalent rate of inflation to 0.8 percent for headline PCE inflation and 1.6 percent for PCEX excluding food and energy. PCEF of prices of food rose at the annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent in Oct-Dec 2011 while PCEE of prices of energy fell at the annual equivalent rate of 10.3 percent. In the fifth wave in Jan-Mar 2012, headline PCE in annual equivalent was 2.8 percent and 2.0 percent excluding food and energy (PCEX). Energy prices of personal consumption (PCEE) increased at the annual equivalent rate of 12.2 percent because of the jump of 1.6 percent in Feb 2012 followed by 0.7 percent in Mar 2012. In the sixth wave, renewed risk aversion caused reversal of carry trades with headline PCE inflation at the annual equivalent rate of 0.6 percent in Apr-May 2012 while PCE inflation excluding food and energy increased at the annual equivalent rate of 1.2 percent. In the seventh wave, further shocks of risk aversion resulted in headline PCE annual equivalent inflation at 0.0 percent in Jun-Jul 2012 with core PCE excluding food and energy at 1.8 percent. In the eighth wave, temporarily relaxed risk aversion with zero interest rates resulted in central PCE inflation at 3.7 percent annual equivalent in Aug-Sep 2012 with PCEX excluding food and energy at 0.6 percent while PCEE energy jumped at 63.8 percent annual equivalent. The program of outright monetary transactions (OTM) of the European Central Bank induced relaxed risk aversion (http://www.ecb.int/press/pr/date/2012/html/pr120906_1.en.html). In the ninth wave, prices collapsed with reversal of carry trade positions in a new episode of risk aversion with central PCE at annual equivalent 0.6 percent in Oct 2012 to Jan 2013 and PCEX at 1.5 percent while energy prices fell at minus 13.6 percent. In the tenth wave, central PCE increased at annual equivalent 3.7 percent in Feb 2013, PCEX at 1.2 percent and PCEE at 63.8 percent. In the eleventh wave, renewed risk aversion resulted in decline in annual equivalent of general PCE prices at 1.2 percent in Mar-Apr 2013 while PCEX increased at 0.6 percent and energy prices fell at 29.3 percent. In the twelfth wave, central PCE increased at 1.6 percent annual equivalent in May-Nov 2013 with PCEX increasing at 1.4 percent, food PCEF increasing at 0.2 percent and energy PCEE increasing at 2.6 percent with the jump of 1.9 percent in Jun 2013. In the thirteenth wave, central PCE increased at annual equivalent 1.8 percent in Dec 2013-Mar 2014 and PCEX at 1.2 percent. PCEE increased at 4.6 percent annual equivalent. In the fourteenth wave, central PCE inflation was 2.1 percent in annual equivalent in Apr-Jul 2014 with PCEX at 2.1 percent and energy prices at 8.1 percent. In the fifteenth wave, central PCE changed at annual equivalent 0.0 percent in Aug-Sep 2014 while PCEX increased at 1.2 percent. PCEF increased at 3.0 percent while PCEE fell at 19.1 percent. Commodity prices have moderated with reallocation of financial investments to carry trades in equities.

Table IV-5, US, Percentage Change from Prior Month of Prices of Personal Consumption

Expenditures, Seasonally Adjusted Monthly ∆%

| PCE | PCEG | PCEG | PCES | PCEX | PCEF | PCEE | |

| 2014 | |||||||

| Sep | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | -0.8 |

| Aug | -0.1 | -0.4 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -2.7 |

| ∆% AE Aug-Sep | 0.0 | -2.4 | -1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.0 | -19.1 |

| Jul | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -0.3 |

| Jun | 0.2 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.7 |

| May | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Apr | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| ∆% AE Apr-Jul | 2.1 | 2.7 | -1.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 8.1 |

| Mar | 0.2 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | -0.1 |

| Feb | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -0.5 |

| Jan | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 2013 | |||||||

| Dec | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| ∆% AE Dec-Mar | 1.8 | -0.6 | -3.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 4.6 |

| Nov | 0.1 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.4 |

| Oct | 0.1 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.9 |

| Sep | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.4 |

| Jul | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 0.4 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| May | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.8 |

| ∆% AE May-Nov | 1.6 | -0.2 | -2.4 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 2.6 |

| Apr | -0.1 | -0.5 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | -2.4 |

| Mar | -0.1 | -0.6 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -3.3 |

| ∆% AE Mar-Apr | -1.2 | -6.4 | -3.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | -29.3 |

| Feb | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4.2 |

| ∆% AE Feb | 3.7 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 63.8 |

| Jan | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | -0.9 |

| 2012 | |||||||

| Dec | 0.0 | -0.4 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | -1.4 |

| Nov | -0.1 | -0.6 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | -3.3 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| ∆% AE Oct-Jan | 0.6 | -2.7 | -1.2 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 2.1 | -13.6 |

| Sep | 0.3 | 0.6 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 3.8 |

| Aug | 0.3 | 0.6 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 |

| ∆% AE Aug-Sep | 3.7 | 7.4 | -2.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | -0.6 | 63.8 |

| Jul | 0.0 | -0.1 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -1.1 |

| Jun | 0.0 | -0.3 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -2.1 |

| ∆% AE Jun-Jul | 0.0 | -2.4 | -2.4 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.2 | -17.6 |

| May | 0.0 | -0.5 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -2.8 |

| Apr | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| ∆% AE Apr- May | 0.6 | -3.0 | -1.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.6 | -15.7 |

| Mar | 0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Feb | 0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Jan | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| ∆% AE Jan- Mar | 2.8 | 3.7 | -0.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 12.2 |

| 2011 | |||||||

| Dec | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | -1.7 |

| Nov | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Oct | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -1.1 |

| ∆% AE Oct- Dec | 0.8 | -0.8 | -1.6 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 | -10.3 |

| Sep | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Aug | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| Jul | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| ∆% AE Jul-Sep | 2.4 | 2.4 | -2.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 5.3 |

| Jun | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | -1.6 |

| May | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| ∆% AE May-Jun | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 4.3 | -1.3 |

| Apr | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 3.3 |

| Mar | 0.4 | 0.7 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 3.2 |

| Feb | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Jan | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| ∆% AE Jan-Apr | 4.0 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 7.8 | 30.1 |

| 2010 | |||||||

| Dec | 0.2 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 4.1 |

| Nov | 0.2 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 0.4 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.1 |

| Sep | 0.1 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Jul | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Jun | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.5 |

| May | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -1.2 |

| Apr | 0.0 | -0.3 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | -0.8 |

| Mar | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | -0.5 |

| Feb | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -1.2 |

| Jan | 0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

Notes: percentage changes in price index relative to the same month a year earlier of PCE: personal consumption expenditures; PCEG: PCE goods; PCEG-D: PCE durable goods; PCES: PCE services; PCEX: PCE excluding food and energy; PCEF: PCE food; PCEE: PCE energy goods and services. AE: annual equivalent.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

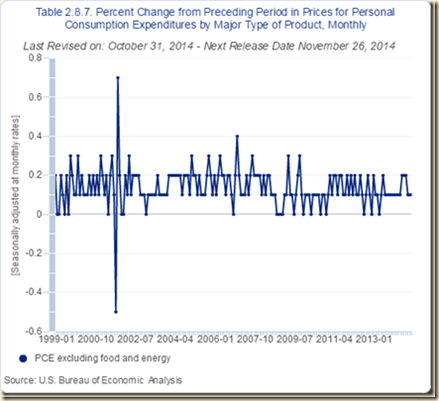

The charts of PCE inflation are also instructive. Chart IV-1 provides the monthly change of headline PCE price index. There is significant volatility in the monthly changes but excluding outliers fluctuations have been in a tight range between 1999 and 2014 around 0.2 percent per month.

Chart IV-1, US, Percentage Change of PCE Price Index from Prior Month, 1999-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

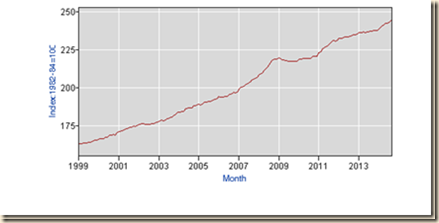

There is much less volatility in the PCE index excluding food and energy shown in Chart IV-2 with monthly percentage changes from 1999 to 2014. With the exception of 2001, there are no negative changes and again changes around 0.2 percent when excluding outliers.

Chart IV-2, US, Percentage Change of PCE Price Index Excluding Food and Energy from Prior Month, 1999-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

Fluctuations in the PCE index of food are much wider as shown in Chart IV-3 by monthly percentage changes from 1999 to 2014. There are also multiple negative changes and positive changes even exceeding 1.0 percent in three months.

Chart IV-3, US, Percentage Change of PCE Price Index Food from Prior Month, 1999-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The band of fluctuation of the PCE price index of energy in Chart IV-4 is much wider. An interesting feature is the abundance of negative changes and large percentages.

Chart IV-4, US, Percentage Change of PCE Price Index Energy from Prior Month, 1999-2014

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm