Global Financial and Economic Risk, World Inflation Waves, Hiring Collapse, Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs and Youth Unemployment

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011, 2012

Executive Summary

I World Inflation Waves

IA World Inflation Waves

IB United States Inflation

IB1 Long-term US Inflation

IB2 Current US Inflation

IB3 Import Export Prices

II Hiring Collapse

IIA Hiring Collapse

IIB Labor Underutilization

IIC Ten Million Fewer Full-time Jobs

IID Youth Unemployment

III World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIIB Appendix on Safe Haven Currencies

IIIC Appendix on Fiscal Compact

IIID Appendix on European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IIIE Appendix Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIIF Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

IV Global Inflation

V World Economic Slowdown

VA United States

VB Japan

VC China

VD Euro Area

VE Germany

VF France

VG Italy

VH United Kingdom

VI Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VII Economic Indicators

VIII Interest Rates

IX Conclusion

References

V World Economic Slowdown. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has revised its World Economic Outlook (WEO) to an environment of lower growth (IMF 2012WEOJan24):

“The global recovery is threatened by intensifying strains in the euro area and fragilities elsewhere. Financial conditions have deteriorated, growth prospects have dimmed, and downside risks have escalated. Global output is projected to expand by 3¼ percent in 2012—a downward revision of about ¾ percentage point relative to the September 2011 World Economic Outlook (WEO).”

The IMF (2012WEOJan24) projects growth of world output of 3.8 percent in 2011 and 3.3 percent in 2012 after 5.2 percent in 2010. Advanced economies would grow at only 1.6 percent in 2011, 1.2 percent in 2012 and 3.9 percent in 2013 after growing at 3.2 percent in 2010. Emerging and developing economies would drive the world economy, growing at 6.2 percent in 2011, 5.4 percent in 2012 and 5.9 percent in 2012 after growing at 7.3 percent in 2010. The IMF is forecasting deceleration of the world economy.

World economic slowing would be the consequence of the mild recession in the euro area in 2012 caused by “the rise in sovereign yields, the effects of bank deleveraging on the real economy and the impact of additional fiscal consolidation” (IMF 2012WEOJan24). After growing at 1.9 percent in 2010 and 1.6 percent in 2010, the economy of the euro area would contract by 0.5 percent in 2012 and grow at 0.8 percent in 2013. The United States would grow at 1.8 percent in both 2011 and 2012 and at 2.2 percent in 2013. The IMF (2012WEO Jan24) projects slow growth in 2012 of Germany at 0.3 percent and of France at 0.2 percent while Italy contracts 2.2 percent and Spain contracts 1.7 percent. While Germany would grow at 1.5 percent in 2013 and France at 1.0 percent, Italy would contract 0.6 percent and Spain 0.3 percent.

The IMF (2012WEOJan24) also projects a downside scenario, in which the critical risk “is intensification of the adverse feedback loops between sovereign and bank funding pressures in the euro area, resulting in much larger and more protracted bank deleveraging and sizable contractions in credit and output.” In this scenario, there is contraction of private investment by an extra 1.75 percentage points in relation to the projections of the WEO with euro area output contracting 4 percent relative to the base WEO projection. The environment could be complicated by failure in medium-term fiscal consolidation in the United States and Japan.

There is significant deceleration in world trade volume in the projections of the IMF (2012WEOJan24). Growth of the volume of world trade in goods and services decelerates from 12.7 percent in 2010 to 6.9 percent in 2011, 3.8 percent in 2012 and 5.4 percent in 2013. Under these projections there would be significant pressure in economies in stress such as Japan and Italy that require trade for growth. Even the stronger German economy is dependent on foreign trade. There is sharp deceleration of growth of exports of advanced economies from 12.2 percent in 2010 to 2.4 percent in 2012. Growth of exports of emerging and developing economies falls from 13.8 percent in 2010 to 6.1 percent in 2012. Another cause of concern in that oil prices in the projections fall only 4.9 percent in 2012, remaining at relatively high levels.

The JP Morgan Global Manufacturing & Services PMI™, produced by JP Morgan and Markit in association with ISM and IPFSM, rose to 55.5 in Feb from 54.5 in Jan, indicating expansion at a faster rate (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9282). This index is highly correlated with global GDP, indicating continued growth of the global economy for nearly two years and a half. The US economy drove growth in the global economy from Dec to Jan. New orders are expanding at a faster rate, increasing from 54.0 in Jan to 54.7 in Feb, suggesting further increase in business ahead. The HSBC Brazil Composite Output Index of the HSBC Brazil Services PMI™, compiled by Markit, rose from 53.8 in Jan to 55.0 in Feb (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9279). Andre Loes, Chief Economist of HSBC in Brazil, finds that the increase of the services HSBC PMI for Brazil from 55.0 in Jan to 57.1 in Feb, which is the highest level since Jul 2007, indicate that the economy may be expanding at a faster rate than anticipated (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9279).

VA United States. Table USA provides the data table for the US.

Table USA, US Economic Indicators

| Consumer Price Index | Feb 12 months NSA ∆%: 2.9; ex food and energy ∆%: 2.2 Jan month ∆%: 0.4; ex food and energy ∆%: 0.1 |

| Producer Price Index | Feb 12 months NSA ∆%: 3.3; ex food and energy ∆% 3.0 |

| PCE Inflation | Jan 12 months NSA ∆%: headline 2.4; ex food and energy ∆% 1.9 |

| Employment Situation | Household Survey: Jan Unemployment Rate SA 8.3% |

| Nonfarm Hiring | Nonfarm Hiring fell from 69.4 million in 2004 to 50.1 million in 2011 or by 19.3 million |

| GDP Growth | BEA Revised National Income Accounts back to 2003 IIIQ2011 SAAR ∆%: 1.8 IVQ2011 ∆%: 3.0 Cumulative 2011 ∆%: 1.6 2011/2010 ∆%: 1.7 |

| Personal Income and Consumption | Jan month ∆% SA Real Disposable Personal Income (RDPI) minus 0.1 |

| Quarterly Services Report | IVQ11/IIIQ11 SA ∆%: |

| Employment Cost Index | IVQ2011 SA ∆%: 0.4 |

| Industrial Production | Feb month SA ∆%: 0.0 Manufacturing Feb SA ∆% 0.3 Feb 12 months SA ∆% 5.1, NSA 5.2 |

| Productivity and Costs | Nonfarm Business Productivity IVQ2011∆% SAAE 0.9; IVQ2011/IVQ2010 ∆% 0.3; Unit Labor Costs IVQ2011 ∆% 2.8; IVQ2011/IVQ2010 ∆%: 3.1 Blog 03/11/2012 |

| New York Fed Manufacturing Index | General Business Conditions From Feb 19.53 to Mar 20.21 |

| Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook Index | General Index from Feb 10.2 to Mar 12.5 |

| Manufacturing Shipments and Orders | Jan New Orders SA ∆%: -1.0; ex transport ∆%: -0.3 |

| Durable Goods | Jan New Orders SA ∆%: minus 4.0; ex transport ∆%: minus 3.2 |

| Sales of New Motor Vehicles | Feb 2012 2,062,683; Feb 2011 1,813,182. Feb SAAR 15.10 million, Dec SAAR 13.56, Feb 2011 SAAR 13.29 million Blog 03/04/12 |

| Sales of Merchant Wholesalers | Jan 2012/Jan 2010 ∆%: Total 11.3; Durable Goods: 14.1; Nondurable |

| Sales and Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers | Jan 12/Jan 11 NSA ∆%: Sales Total Business 8.6; Manufacturers 8.4 |

| Sales for Retail and Food Services | Feb 2012/Feb 2011 ∆%: Retail and Food Services 8.2; Retail ∆% 8.0 |

| Value of Construction Put in Place | Jan SAAR month SA ∆%: minus 0.1 Jan 12-month NSA: 8.0 |

| Case-Shiller Home Prices | Dec 2011/Dec 2010 ∆% NSA: 10 Cities minus 3.9; 20 Cities: minus 4.0 |

| FHFA House Price Index Purchases Only | Dec SA ∆% 0.7; |

| New House Sales | Jan 2012 month SAAR ∆%: |

| Housing Starts and Permits | Jan Starts month SA ∆%: 1.5; Permits ∆%: 0.7 |

| Trade Balance | Balance Jan SA -$52,565 million versus Dec -$50,421 million |

| Export and Import Prices | Feb 12 months NSA ∆%: Imports 4.5; Exports 1.5 |

| Consumer Credit | Jan ∆% annual rate: 8.6 |

| Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term Treasury Securities | Nov Net Foreign Purchases of Long-term Treasury Securities: $101.0 billion Jan versus Dec $19.1 billion |

| Treasury Budget | Fiscal Year 2012/2011 ∆%: Receipts 2.8; Outlays -2.4; Individual Income Taxes 0.6 Deficit Fiscal Year 2012 Oct-Feb $580,830 million CBO Forecast 2012FY Deficit $1.079 trillion Blog 03/18/2012 |

| Flow of Funds | IVQ2011 ∆ since 2007 Assets -$7315B Real estate -$5183B Financial -$2507 Net Worth -$6743 Blog 03/11/12 |

| Current Account Balance of Payments | IVQ2011 -$124B %GDP 3.2 Blog 03/18/12 |

Links to blog comments in Table USA:

03/12/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/thirty-million-unemployed-or_11.html

03/04/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/mediocre-economic-growth-flattening_04.html

02/26/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/decline-of-united-states-new-house_26.html

02/19/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states_19.html

ndustrial production was flat in Feb and increased 4.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb, as shown in Table VA-1, with all data seasonally adjusted. In the six months ending in Jan, industrial production grew at the annual equivalent rate of 3.7 percent. Business equipment rose 0.6 percent in Feb and grew 10.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb and at the annual equivalent rate of 14.1 percent in the six months ending in Feb. Capacity utilization of total industry is analyzed by the Fed in its report (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/Current/): “The capacity utilization rate for total industry decreased to 78.7 percent, a rate 2.2 percentage points below its long-run (1972--2010) average.” Manufacturing contributed $1,229 billion to US national income of $12,643 billion without capital consumption adjustment in 2010, or 9 percent of the total, according to data of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm).

Table VA-1, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization, SA, ∆%, %

| 2011 | Feb | Jan | Dec | Nov | Oct | Sep | Jan 12/ Feb 11 |

| Total | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| Market | |||||||

| Final Products | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| Consumer Goods | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | -0.7 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 1.5 |

| Business Equipment | 0.6 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 10.8 |

| Non | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.5 | -0.7 | -0.3 | 0.4 | 3.9 |

| Construction | 1. | -0.1 | 3.0 | 0.2 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 7.5 |

| Materials | -0.3 | -0.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 4.1 |

| Industry Groups | |||||||

| Manufacturing | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | -0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 5.1 |

| Mining | -1.2 | -1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 6.1 |

| Utilities | 0.0 | -2.2 | -3.0 | 0.1 | -1.2 | -1.4 | -5.6 |

| Capacity | 78.7 | 78.8 | 78.5 | 77.9 | 77.9 | 77.7 | 1.2 |

Sources: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/current/

Manufacturing increased 0.3 percent in Feb and 5.2 percent in 12 months. A longer perspective of manufacturing in the US is provided by Table VA-2. There has been evident deceleration of manufacturing growth in the US from 2010 and the first three months of 2011 as shown by 12 months rates of growth. The rates of decline of manufacturing in 2009 are quite high with a drop of 18.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr 2009. Manufacturing recovered from this decline and led the recovery from the recession. Rates of growth appear to be returning to the levels at 3 percent or higher in the annual rates before the recession.

Table VA-2, US, Monthly and 12-Month Rates of Growth of Manufacturing ∆%

| Month SA ∆% | 12 Months NSA ∆% | |

| Feb 2012 | 0.3 | 5.2 |

| Jan | 1.1 | 4.7 |

| Dec 2011 | 1.5 | 4.4 |

| Nov | -0.2 | 4.1 |

| Oct | 0.5 | 4.4 |

| Sep | 0.4 | 4.2 |

| Aug | 0.3 | 3.7 |

| Jul | 0.8 | 3.8 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 3.6 |

| May | 0.2 | 3.6 |

| Apr | -0.6 | 4.5 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 6.0 |

| Feb | 0.1 | 6.2 |

| Jan | 0.7 | 6.2 |

| Dec 2010 | 1.0 | 6.2 |

| Nov | 0.2 | 5.3 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 6.2 |

| Sep | 0.2 | 5.9 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 6.6 |

| Jul | 0.8 | 7.6 |

| Jun | -0.1 | 8.1 |

| May | 1.1 | 7.8 |

| Apr | 0.7 | 6.1 |

| Mar | 0.9 | 5.9 |

| Feb | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 6.2 |

| Dec 2009 | 0.2 | -3.2 |

| Nov | 0.8 | -5.9 |

| Oct | -0.04 | -8.9 |

| Sep | 0.8 | -10.3 |

| Aug | 1.0 | -13.3 |

| Jul | 1.3 | -14.9 |

| Jun | -0.3 | -17.4 |

| May | -1.2 | -17.4 |

| Apr | -0.8 | -18.1 |

| Mar | -2.0 | -17.1 |

| Feb | 0.1 | -16.0 |

| Jan | -2.7 | -16.5 |

| Dec 2008 | -3.1 | -14.1 |

| Nov | -2.4 | -11.5 |

| Oct | -0.6 | -9.2 |

| Sep | -3.4 | -9.0 |

| Aug | -1.4 | -5.5 |

| Jul | -1.1 | -4.1 |

| Jun | -0.6 | -3.5 |

| May | -0.6 | -2.8 |

| Apr | -1.2 | -1.5 |

| Mar | -0.4 | -0.9 |

| Feb | -0.5 | 0.6 |

| Jan | -0.3 | 1.9 |

| Dec 2007 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| Nov | 0.3 | 3.2 |

| Oct | -0.5 | 2.8 |

| Sep | 0.5 | 3.2 |

| Aug | -0.5 | 2.9 |

| Jul | 0.3 | 3.8 |

| Jun | 0.3 | 3.3 |

| May | -0.2 | 3.5 |

| Apr | 0.7 | 4.0 |

| Mar | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| Feb | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| Jan | -0.3 | 1.8 |

| Dec 2006 | 3.2 | |

| Dec 2005 | 1.4 | |

| Dec 2004 | 2.8 | |

| Dec 2003 | 1.7 |

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/current/table1.htm

Chart VA-1 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System provides industrial production, manufacturing and capacity since the 1970s. There was acceleration of growth of industrial production, manufacturing and capacity in the 1990s because of rapid growth of productivity in the US (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), 135-44). The slopes of the curves flatten in the 2000s. Production and capacity have not recovered to the levels before the global recession.

Chart VA-1, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/current/ipg1.gif

The modern industrial revolution of Jensen (1993) is captured in Chart VA-2 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (for the literature on M&A and corporate control see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009a), 143-56, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), 49-59, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 46-49). The slope of the curve of total industrial production accelerates in the 1990s to a much higher rate of growth than the curve excluding high-technology industries. Growth rates decelerate into the 2000s and output and capacity utilization have not recovered fully from the strong impact of the global recession. Growth in the current cyclical expansion has been more subdued than in the prior comparably deep contractions in the 1970s and 1980s. Chart VA-2 shows that the past recessions after World War II are the relevant ones for comparison with the recession after 2007 instead of common comparisons with the Great Depression. The bottom left-hand part of Chart VA-2 shows the strong growth of output of communication equipment, computers and semiconductor that continued from the 1990s into the 2000s. Output of computers and semiconductors has already surpassed the level before the global recession.

Chart VA-2, US, Industrial Production, Capacity and Utilization of High Technology Industries

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/current/ipg3.gif

Additional detail on industrial production and capacity utilization is provided in Chart VA-3 of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Production of consumer durable goods fell sharply during the global recession by more than 30 percent and is still around 5 percent below the level before the contraction. Output of nondurable consumer goods fell around 10 percent and is some 5 percent below the level before the contraction. Output of business equipment fell sharply during the contraction of 2001 but began rapid growth again after 2004. An important characteristic is rapid growth of output of business equipment in the cyclical expansion after sharp contraction in the global recession. Output of defense and space only suffered reduction in the rate of growth during the global recession and surged ahead of the level before the contraction. Output of construction supplies collapsed during the global recession and is well below the level before the contraction. Output of energy materials was stagnant before the contraction but has recovered sharply above the level before the contraction.

Chart VA-3, US, Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g17/current/ipg2.gif

The index of general business conditions of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Empire State Manufacturing Survey shows significant, continuing improvement from revised minus 7.43 in Sep to 20.21 in Mar, as shown in Table VA-3. The index had been registering negative changes in the five months from Jun to Oct. The new orders segment improved more mildly from minus 7.52 in Sep to 13.79, declining to 6.84 in Mar. There is positive reading in shipments from revised minus 8.28 in Sep to positive 22.79 in Feb, declining to 18.21 in Mar. The segment of number of employees fell back into contraction territory from minus 5.43 in Sep to minus 3.66 in Nov but recovered strongly to 13.58 in Mar together with number of weekly hours worked. Expectations for the next six months of the general business conditions index peaked at 54.87 in Jan, declining to a still strong 47.50 in Mar. Expectations of new orders also peaked at 53.85 in Jan, declining to a still strong 44.71 in Mar. There is a similar pattern of strong recovery in shipments, number of employees and hours worked.

Table VA-3, US, New York Federal Reserve Bank Empire State Manufacturing Survey Index SA

| General | New Orders | Ship-ments | # Workers | Average Work-week | |

| Current | |||||

| Mar 2012 | 20.21 | 6.84 | 18.21 | 13.58 | 18.52 |

| Feb | 19.53 | 9.73 | 22.79 | 11.76 | 7.06 |

| Jan | 13.48 | 13.70 | 21.69 | 12.09 | 6.59 |

| Dec 2011 | 8.19 | 5.99 | 20.06 | 2.33 | -2.33 |

| Nov | 0.80 | -0.82 | 11.70 | -3.66 | 2.44 |

| Oct | -7.22 | -0.26 | 2.89 | 3.37 | -4.49 |

| Sep | -7.43 | -7.52 | -8.28 | -5.43 | -2.17 |

| Six Months | |||||

| Mar 2012 | 47.50 | 41.98 | 43.21 | 32.10 | 20.99 |

| Feb | 50.38 | 44.71 | 49.41 | 29.41 | 18.82 |

| Jan | 54.87 | 53.85 | 52.75 | 28.57 | 17.58 |

| Dec 2011 | 45.61 | 54.65 | 51.16 | 24.42 | 22.09 |

| Nov | 32.06 | 35.37 | 36.59 | 14.63 | 8.54 |

| Oct | 13.99 | 12.36 | 17.98 | 6.74 | -2.25 |

| Sep | 22.93 | 13.04 | 13.04 | 0.0 | -6.52 |

Source: http://www.newyorkfed.org/survey/empire/empiresurvey_overview.html

The Philadelphia Business Outlook Survey in Table VA-4 provides an optimistic reading in Oct with the movement to 10.8 away from the contraction zone of minus 22.7 in Sep and recovered to 12.5 in Mar from the decline to 3.1 in Nov. New orders were signaling increasing future activity, rising from contraction at minus 5.5 in Sep to positive reading but registered only 3.3 in Mar. There is similar behavior in shipments as in new orders. Employment or number of employees fell to 1.1 in Feb, near the contraction border of zero, but rose to 6.8 in Mar. The average work week also fell from 10.1 in Feb to 2.7 in Mar. Most indexes of expectations for the next six months are showing sharp increases but interruptions in Feb and Mar for the general index, new orders and shipments. Employment and average work week increased from Jan into Feb and Mar 2012.

Table VA-4, FRB of Philadelphia Business Outlook Survey Diffusion Index SA

| General | New Orders | Ship-ments | # Workers | Average Work-week | |

| Current | |||||

| Mar 12 | 12.5 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 2.7 |

| Feb | 10.2 | 11.7 | 15.0 | 1.1 | 10.1 |

| Jan | 7.3 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 11.6 | 5.0 |

| Dec 11 | 6.8 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 11.5 | 2.8 |

| Nov | 3.1 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 10.6 | 7.1 |

| Oct | 10.8 | 8.5 | 13.6 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

| Sep | -12.7 | -5.5 | -16.6 | 7.3 | -6.2 |

| Aug | -22.7 | -22.2 | -8.9 | -0.9 | -11.2 |

| Jul | 6.2 | 0.5 | 8.2 | 9.5 | -3.9 |

| Future | |||||

| Mar 12 | 32.9 | 36.4 | 31.3 | 21.8 | 11.2 |

| Feb | 33.3 | 32.5 | 29.0 | 22.5 | 10.8 |

| Jan | 49.0 | 49.7 | 48.2 | 19.1 | 9.2 |

| Dec 11 | 40.0 | 44.1 | 36.4 | 10.8 | 4.5 |

| Nov | 37.7 | 36.9 | 35.5 | 25.2 | 4.0 |

| Oct | 28.8 | 28.1 | 29.0 | 15.5 | 8.4 |

| Sep | 25.2 | 24.6 | 27.1 | 14.0 | 6.8 |

| Aug | 6.3 | 20.6 | 18.4 | 11.2 | -0.7 |

| Jul | 25.8 | 31.2 | 26.1 | 12.9 | 6.6 |

Source: http://www.philadelphiafed.org/index.cfm

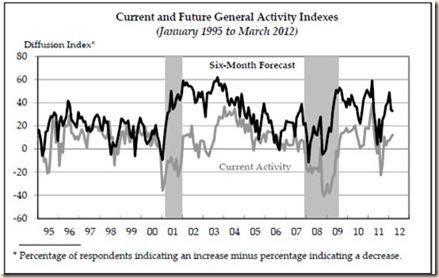

Chart VA-4 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia is very useful, providing current and future general activity indexes from Jan 1995 to Mar 2012. The shaded areas are the recession cycle dates of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (http://www.nber.org/cycles.html). The Philadelphia Fed index dropped during the initial period of recession and then led the recovery, as industry overall. There was a second decline of the index into 2011 followed now by what hopefully could be renewed strength from late 2011 into Jan 2012 but marginal weakness in Feb with mild recovery in Mar.

Chart VA-4, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Outlook Survey, Current and Future Activity Indexes

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

http://www.philadelphiafed.org/index.cfm

Chart VA-5 of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia provides the index of new orders of the Business Outlook Survey. Strong growth in the beginning of 2011 was followed by a bump after Mar that lasted until Oct. The strength of the first quarter of 2011 has not been recovered.

Chart VA-5, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Outlook Survey, Current New Orders Diffusion Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Growth rates and levels of sales in billions of dollars of manufacturers, retailers and merchant wholesalers are provided in Table VA-5. Total business sales rose 0.4 percent in Jan after 0.9 percent in Dec and were up by 8.6 percent in Jan 2012 relative to Jan 2011. Sales of manufacturers increased 0.9 percent in Jan after increasing 0.8 percent in Dec and rose 8.4 percent in the 12 months to Jan 2012. Retailers’ increased 0.4 percent in Jan after increasing 0.3 percent in Dec and 5.8 percent in 12 months ending in Jan. Sales of merchant wholesalers fell 0.1 percent in Jan after increasing 1.4 percent in Dec and grew 11.3 percent in 12 months. These data are not adjusted for price changes such that they reflect increases in both quantities and prices.

Table VA-5, US, Percentage Changes for Sales of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers

| Jan 12/ Dec 11 | Jan 2012 | Dec 11/ Nov 11 ∆% SA | Jan 12/ Jan 11 | |

| Total Business | 0.4 | 1,140.4 | 0.9 | 8.6 |

| Manufacturers | 0.9 | 426.3 | 0.8 | 8.4 |

| Retailers | 0.4 | 323.1 | 0.3 | 5.8 |

| Merchant Wholesalers | -0.1 | 391.0 | 1.4 | 11.3 |

Source: http://www.census.gov/mtis/www/data/pdf/mtis_current.pdf

Businesses added to inventories to replenish stocks in an environment of strong sales. Retailers added 1.1 percent to inventories in Jan and 0.5 percent in Dec with growth of 4.6 percent in 12 months, as shown in Table VA-6. Total business increased inventories by 0.7 percent in Jan, 0.6 percent in Dec and 7.4 percent in 12 months. Inventories sales/ratios of total business continued at a level close to 1.27 under judicious management to avoid costs and risks. Inventory/sales ratios of manufacturers and retailers are higher than for merchant wholesalers. There is stability in inventory/sales ratios in individual months and relative to a year earlier.

Table VA-6, US, Percentage Changes for Inventories of Manufacturers, Retailers and Merchant Wholesalers and Inventory/Sales Ratios

| Inventory Change | Jan 12 | Jan 12/ Dec 11 ∆% SA | Dec 11/ Nov 11 ∆% SA | Jan 12/ Jan 11 ∆% NSA |

| Total Business | 1,559.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 7.4 |

| Manufacturers | 609.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 8.5 |

| Retailers | 469.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 4.6 |

| Merchant | 479.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 9.0 |

| Inventory/ | Jan 12 | Jan 2012 SA | Dec 2011 SA | Jan 2011 SA |

| Total Business | 1,559.3 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.26 |

| Manufacturers | 609.8 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 1.31 |

| Retailers | 469.7 | 1.33 | 1.32 | 1.35 |

| Merchant Wholesalers | 479.9 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.14 |

Source: http://www.census.gov/mtis/www/data/pdf/mtis_current.pdf

Inventories follow business cycles. When recession hits sales inventories pile up, declining with expansion of the economy. In a fascinating classic opus, Lloyd Meltzer (1941, 129) concludes:

“The dynamic sequences (I) through (6) were intended to show what types of behavior are possible for a system containing a sales output lag. The following conclusions seem to be the most important:

(i) An economy in which business men attempt to recoup inventory losses will always undergo cyclical fluctuations when equilibrium is disturbed, provided the economy is stable.

This is the pure inventory cycle.

(2) The assumption of stability imposes severe limitations upon the possible size of the marginal propensity to consume, particularly if the coefficient of expectation is positive.

(3) The inventory accelerator is a more powerful de-stabilizer than the ordinary acceleration principle. The difference' in stability conditions is due to the fact that the former allows for replacement demand whereas the usual analytical formulation of the latter does not. Thus, for inventories, replacement demand acts as a de-stabilizer. Whether it does so for all types of capital goods is a moot question, but I believe cases may occur in which it does not.

(4) Investment for inventory purposes cannot alter the equilibrium of income, which depends only upon the propensity to consume and the amount of non-induced investment.

(5) The apparent instability of a system containing both an accelerator and a coefficient of expectation makes further investigation of possible stabilizers highly desirable.”

Chart VA-6 shows the increase in the inventory/sales ratios during the recessions of 2001 and 2007-2009. The inventory/sales ratio fell during the expansions. The inventory/sales ratio declined to a trough in 2011, climbed and then stabilized at current levels.

Chart VA-6, Total Business Inventories/Sales Ratios 2002 to 2011

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www2.census.gov/retail/releases/historical/mtis/img/mtisbrf.gif

Sales of retail and food services increased 1.1 percent in Feb after 0.6 percent in Jan and increased 8.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb, as shown in Table VA-7. Excluding motor vehicles and parts, retail sales increased 0.9 percent in Feb after increasing 1.1 percent in Jan and growing 8.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb. Sales of motor vehicles and parts increased 1.6 percent in Feb after falling 1.6 percent in Jan. Gasoline station sales jumped 3.3 percent in Feb in fluctuating prices of gasoline, increasing 1.9 percent in Jan and 11.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Feb.

Table VA-7, US, Percentage Change in Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services, ∆%

| Feb/Jan ∆% SA | Jan/Dec ∆% SA | Jan-Feb 2012 Billion Dollars NSA | 12 Months Feb 2012 from Feb 2011 ∆% NSA | |

| Retail and Food Services | 1.1 | 0.6 | 742.5 | 8.2 |

| Excluding Motor Vehicles and Parts | 0.9 | 1.1 | 609.9 | 8.0 |

| Motor Vehicles & Parts | 1.6 | -1.6 | 132.6 | 9.2 |

| Retail | 1.1 | 0.5 | 661.1 | 8.0 |

| Building Materials | 1.4 | 1.4 | 40.7 | 15.5 |

| Food and Beverage | 0.3 | 1.1 | 99.7 | 5.1 |

| Grocery | 0.3 | 1.1 | 90.3 | 5.0 |

| Health & Personal Care Stores | 0.1 | -0.1 | 45.7 | 4.1 |

| Clothing & Clothing Accessories Stores | 1.8 | 0.7 | 31.9 | 8.5 |

| Gasoline Stations | 3.3 | 1.9 | 83.4 | 11.2 |

| General Merchandise Stores | -0.1 | 0.8 | 95.9 | 5.2 |

| Food Services & Drinking Places | 0.8 | 1.4 | 81.3 | 9.9 |

Source: http://www.census.gov/retail/marts/www/marts_current.pdf

Chart VA-7 of the US Bureau of the Census shows percentage change of retails and food services sales. Sep was strong in multiple categories but the strength did not continue in Oct, Nov and Dec. Feb was stronger a jump in auto sales after the fall in Jan.

Chart VA-7, US, Percentage Change of Retail and Food Services Sales

Source: US Census Bureau

http://www2.census.gov/retail/releases/historical/marts/img/martsbrf.gif

Twelve-month rates of growth of US sales of retail and food services in Feb from 2000 to 2011 are shown in Table VA-8. Nominal sales have been dynamic in 2011 and 2010 after decline of 12.7 percent in 2009 and increase of only 3.0 percent in 2007. It is difficult to separate price and quantity effects in these nominal data.

Table VA-8, US, Percentage Change in 12-Month Sales for Retail and Food Services, ∆% NSA

| Feb | 12 Months ∆% |

| 2012 | 10.3 |

| 2011 | 9.2 |

| 2010 | 14.2 |

| 2009 | -12.7 |

| 2008 | 6.4 |

| 2007 | 3.0 |

| 2006 | 6.4 |

| 2005 | 4.5 |

| 2004 | 9.1 |

| 2003 | 2.2 |

| 2002 | 2.3 |

| 2001 | -1.2 |

| 2000 | 13.6 |

Source: http://www.census.gov/retail/

The US Treasury budget for fiscal year 2012 in the first five months of Dec, Nov and Oct 2011 and Jan and February 2012 is shown in Table VA-9. Receipts increased 2.8 percent in the first five months of fiscal year 2012 relative to the same five months in fiscal year 2011 or Oct-Dec 2010 and Jan and Feb 2011. Individual income taxes have grown 0.6 percent relative to the same period a year earlier in sharp decline of the rate of growth of 4.9 percent cumulatively in the first four months. Outlays were lower by 2.4 percent relative to a year earlier compared with decline of 3.2 percent in the first four months. The final two rows of Table VA-9 provide the projection of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) of the deficit for fiscal year 2012 at $1.3 trillion not very different from that in fiscal year 2011. The deficits from 2009 to 2012 exceed one trillion dollars per year, adding to $5.1 trillion in four years, which is the worst fiscal performance since World War II.

Table VA-9, US, Treasury Budget in Fiscal Year to Date Million Dollars

| Fiscal Year 2012 | Oct 2011 to Feb 2012 | Oct 2010 to Feb 2011 | ∆% |

| Receipts | 893,169 | 869,003 | 2.8 |

| Outlays | 1,473,999 | 1,510,266 | -2.4 |

| Deficit | -580,830 | -641,264 | NA |

| Individual Income Taxes | 425,253 | 422,841 | 0.6 |

| Social Insurance | 220,318 | 233,977 | -5.8 |

| Receipts | Outlays | Deficit (-), Surplus (+) | |

| $ Billions | |||

| CBO Forecast Fiscal Year 2012 | 2,522 | 3,601 | -1,079 |

| Fiscal Year 2011 | 2,302 | 3,599 | -1,296 |

| Fiscal Year 2010 | 2,162 | 3,456 | -1,294 |

| Fiscal Year 2009 | 2,105 | 3,518 | -1,413 |

| Fiscal Year 2008 | 2,524 | 2,983 | -459 |

Source: http://www.fms.treas.gov/mts/index.html

CBO (2011AugBEO); Office of Management and Budget. 2011. Historical Tables. Budget of the US Government Fiscal Year 2011. Washington, DC: OMB; CBO. 2011JanBEO. Budget and Economic Outlook. Washington, DC, Jan.

Risk aversion channeled funds toward US long-term and short-term securities as shown in Table VA-10. Net foreign purchases of US long-term securities (row C in Table VA-10) rose from 19.1 in Dec 2011 to 101.0 in Jan 2012. Foreign (residents) purchases minus sales of US long-term securities (row A in Table VA-10) in Dec of minus $19.4 billion increased to $94.7 billion in Jan 2012. Net US (residents) purchases of long-term foreign securities (row B in Table VA-10) in Dec were $38.5 billion in Dec but fell to $6.3 billion in Jan. In Jan,

C = A + B = $94.7 billion + $6.3 billion = $101.0 billion

There is strengthening demand in Table VA-10 in Jan in A1 private purchases by residents overseas of US long-term securities of $60.8 billion of which increases in A11 Treasury securities $49.9 billion and A12 $9.8 billion agency securities and decrease of corporate bonds by $1.3 billion and increase of $2.4 billion in equities. Official purchases of Treasury securities in row A21 increased $33.1 billion. Row D shows sharp decrease in Jan in purchases of short-term dollar denominated obligations. Foreign private holdings of US Treasury bills fell $28.8 billion (row D11) with foreign official holdings decreasing $8.0 billion and the category other increasing $2.7 billion. Risk aversion of losses in foreign securities dominates decisions to accept zero interest rates in Treasury securities with no perception of principal losses. In the case of long-term securities, investors prefer to sacrifice inflation and possible duration risk to avoid principal losses.

Table VA-10, Net Cross-Borders Flows of US Long-Term Securities, Billion Dollars, NSA

| Jan 2011 12 Months | Jan 2012 12 Months | Dec 2011 | Jan 2012 | |

| A Foreign Purchases less Sales of | 948.1 | 459.3 | -19.4 | 94.7 |

| A1 Private | 782.1 | 284.2 | -9.8 | 60.8 |

| A11 Treasury | 501.4 | 254.9 | 5.4 | 49.9 |

| A12 Agency | 149.5 | 65.3 | 16.4 | 9.8 |

| A13 Corporate Bonds | 10.8 | -45.1 | -19.3 | -1.3 |

| A14 Equities | 120.3 | 9.2 | -12.3 | 2.4 |

| A2 Official | 166.0 | 175.1 | -9.5 | 34.0 |

| A21 Treasury | 189.7 | 159.0 | -20.3 | 33.1 |

| A22 Agency | -24.5 | 13.3 | 10.8 | -0.2 |

| A23 Corporate Bonds | 0.0 | -0.7 | -1.4 | 0.0 |

| A24 Equities | 0.8 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| B Net US Purchases of LT Foreign Securities | -121.3 | -90.6 | 38.5 | 6.3 |

| B1 Foreign Bonds | -47.2 | -33.0 | 28.2 | 11.1 |

| B2 Foreign Equities | -74.1 | -57.7 | 10.3 | -4.8 |

| C Net Foreign Purchases of US LT Securities | 826.8 | 368.7 | 19.1 | 101.0 |

| D Increase in Foreign Holdings of Dollar Denominated Short-term | -67.0 | -106.7 | -18.0 | -34.1 |

| D1 US Treasury Bills | -25.0 | -69.7 | -1.6 | -36.9 |

| D11 Private | 38.1 | 22.9 | 19.8 | -28.8 |

| D12 Official | -63.0 | -89.3 | -21.4 | -8.0 |

| D2 Other | -42.0 | -37.0 | -16.5 | 2.7 |

C = A + B;

A = A1 + A2

A1 = A11 + A12 + A13 + A14

A2 = A21 + A22 + A23 + A24

B = B1 + B2

D = D1 + D2

D1 = D11 + D12

Sources: http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Pages/ticpress.aspx

Table VA-11 provides major foreign holders of US Treasury securities. China is the largest holder with $1159.5 billion in Jan 2012, decreasing 0.4 percent from $1154.7 billion in Jan 2011. Japan increased its holdings from $886.0 billion in Jan 2011 to $1079.0 billion in Jan 2012. The United Kingdom decreased its holdings to $142.3 billion in Jan 2012 relative to $277.6 billion in Jan 2011. Caribbean banking centers increased their holdings from $165.3 billion in Jan 2011 to $227.8 billion in Jan 2012. Total foreign holdings of Treasury securities rose from $4435.6 billion in Jan 2011 to $5048.0 billion in Jan 2011, or 13.8 percent. The US continues to finance its fiscal and balance of payments deficits with foreign savings.

Table VA-11, US, Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities $ Billions at End of Period

| Jan 2012 | Dec 2011 | Jan 2011 | |

| Total | 5048.0 | 5001.9 | 4435.7 |

| China | 1159.5 | 1151.9 | 1154.7 |

| Japan | 1079.0 | 1058.2 | 886.0 |

| Oil Exporters | 258.8 | 258.7 | 215.5 |

| United Kingdom | 142.3 | 112.4 | 277.6 |

| Caribbean Banking Centers | 227.8 | 227.6 | 165.3 |

| Brazil | 229.1 | 226.9 | 191.2 |

| Taiwan | 177.9 | 177.3 | 157.3 |

| Switzerland | 145.4 | 142.5 | 106.1 |

| Luxembourg | 138.7 | 150.6 | 79.1 |

| Russia | 142.5 | 149.5 | 139.3 |

| Hong Kong | 130.3 | 121.7 | 127.6 |

Source:

http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Pages/ticsec2.aspx#ussecs

http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Documents/mfh.txt

The current account of the US balance of payments is provided in Table VA-13 for IVQ2010 and IVQ2011. The US has a large deficit in goods or exports less imports of goods but it has a surplus in services that helps to reduce the trade account deficit or exports less imports of goods and services. The current account deficit of the US declined from $123.4 billion in IIQ2010, or 3.3 percent of GDP to $107.6 billion in IIIQ2011, or 2.8 percent of GDP, but increased to $124.1 billion in IVQ2011, or 3.2 percent of GDP. In IVQ2010, as shown in Table VA-13, the deficit reached $112.2 billion or 3.3 percent of GDP. The ratio of the current account deficit to GDP has stabilized around 3 percent of GDP compared with much higher percentages before the recession (see Pelaez and Pelaez, The Global Recession Risk (2007), Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 183-94, Government Intervention in Globalization (2008c), 167-71). The current account deficit reached 6.1 percent of GDP in 2006. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the US Department of Commerce explains that “most of the increase in the current account deficit [from IIIQ2011 to IVQ2011] was due to a decrease in the surplus on income and an increase in the deficit on goods and services” (http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/international/transactions/2012/pdf/trans411.pdf 1).

Table VA-12, US Balance of Payments, Millions of Dollars NSA

| IVQ2010 | IVQ2011 | Difference | |

| Goods Balance | -159,245 | -186,345 | -27,100 |

| X Goods | 342,659 | 380,377 | 11.0 ∆% |

| M Goods | -501,904 | -566,722 | 12.9 ∆% |

| Services Balance | 40,496 | 45,280 | 4,784 |

| X Services | 142,088 | 155,012 | 9.1 ∆% |

| M Services | -101,592 | -109,732 | 8.0 ∆% |

| Balance Goods and Services | -118,749 | -141,066 | -22,317 |

| Balance Income | 39,930 | 50,250 | 10,320 |

| Unilateral Transfers | -33,360 | -33,290 | -70 |

| Current Account Balance | -112,179 | -124,105 | -11,926 |

| % GDP | IIQ2011 | IIIQ2011 | IVQ2011 |

| 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

X: exports; M: imports

Balance on Current Account = Balance on Goods and Services + Balance on Income + Unilateral Transfers

Source: http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm#bop

Chart VA-8 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the Department of Commerce shows on the lower negative panel the sharp increase in the deficit in goods and the deficits in goods and services from 1960 to 2011. The upper panel shows the increase in the surplus in services that was insufficient to contain the increase of the deficit in goods and services. The adjustment during the global recession has been in the form of contraction of economic activity that reduced demand for goods.

Chart VA-8, US, Balance of Goods, Balance on Services and Balance on Goods and Services, 1960-2010, Millions of Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm

Chart VA-9 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows exports and imports of goods and services from 1960 to 2011. Exports of goods and services in the upper positive panel have been quite dynamic but have not compensated for the sharp increase in imports of goods. The US economy apparently has become less competitive in goods than in services.

Chart VA-9, US, Exports and Imports of Goods and Services, 1960-2010, Millions of Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm

Chart VA-10 of the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows the US balance on current account from 1960 to 2011. The sharp devaluation of the dollar resulting from unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and elimination of auctions of 30-year Treasury bonds did not adjust the US balance of payments. Adjustment only occurred after the contraction of economic activity during the global recession.

Chart VA-10, US, Balance on Current Account, 1960-2010, Millions of Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm

Chart VA-11of the Bureau of Economic Analysis provides real GDP in the US from 1960 to 2011. The contraction of economic activity during the global recession was a major factor in the reduction of the current account deficit as percent of GDP.

Chart VA-11, US, Real GDP, 1960-2010, Billions of Chained 2005 Dollars

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

VB. Japan. The Markit/JMMA Purchasing Managers’ Index™ (PMI™) was mostly unchanged from 51.1 in Jan to 51.2 in Feb but still suggesting only marginal growth in private sector economic activity (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9261). New export business grew for the first time in eleven months with improvement in demand both internal and from abroad. Alex Hamilton, economist at Markit and author of the report finds continuing growth in manufacturing and services (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9261). Table JPY provides the country table for Japan.

Table JPY, Japan, Economic Indicators

| Historical GDP and CPI | 1981-2010 Real GDP Growth and CPI Inflation 1981-2010 |

| Corporate Goods Prices | Feb ∆% 0.2 |

| Consumer Price Index | Jan NSA ∆% 0.2 |

| Real GDP Growth | IVQ2011 ∆%: -0.2 on IIIQ2011; IVQ2011 SAAR minus 0.7% |

| Employment Report | Jan Unemployed 2.91 million Change in unemployed since last year: minus 190 thousand |

| All Industry Indices | Dec month SA ∆% 1.3 Blog 02/26/12 |

| Industrial Production | Jan SA month ∆%: 1.9 |

| Machine Orders | Total Jan ∆% 21.6 Private ∆%: 4.6 |

| Tertiary Index | Jan month SA ∆% minus 1.7 |

| Wholesale and Retail Sales | Jan 12 months: |

| Family Income and Expenditure Survey | Jan 12 months ∆% total nominal consumption minus 2.1, real minus 2.3 Blog 03/04/12 |

| Trade Balance | Exports Jan 12 months ∆%: minus 9.3 Imports Jan 12 months ∆% +9.8 Blog 02/26/12 |

Links to blog comments in Table JPY:

03/11/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/thirty-million-unemployed-or_11.html

03/04/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/mediocre-economic-growth-flattening_04.html

02/26/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/decline-of-united-states-new-house_26.html

07/31/11: http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/growth-recession-debt-financial-risk.html

Japan’s industrial production increased during two consecutive months by 3.8 percent in Dec 2011 and revised 1.9 percent in Jan 2012, reducing the percentage decline in 12 months from minus 4.3 percent in Dec to minus 1.2 percent in Jan 2012, as shown in Table VIIB-1. Monthly industrial production had climbed in every month since the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011, with exception of Sep but fell again in Nov. Industrial production was higher in 12 months for the first month in Aug by 0.4 percent and again in Oct by 0.1 percent but fell 4.2 percent in Nov and 4.3 percent in Dec 2011 relative to a year earlier. Industrial production fell 21.9 percent in 2009 after falling 3.4 percent in 2008 but recovered 16.4 percent in 2010. The annual average in calendar year 2011 fell 3.5 percent largely because of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011.

Table VB-1, Japan, Industrial Production ∆%

| ∆% Month SA | ∆% 12 Months NSA | |

| Jan 2012 | 1.9 | -1.3 |

| Dec 2011 | 3.8 | -4.3 |

| Nov | -2.7 | -4.2 |

| Oct | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| Sep | -3.3 | -3.3 |

| Aug | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Jul | 0.4 | -3.0 |

| Jun | 3.8 | -1.7 |

| May | 6.2 | -5.5 |

| Apr | 1.6 | -13.6 |

| Mar | -15.5 | -13.1 |

| Feb | 1.8 | 2.9 |

| Jan | 0.0 | 4.6 |

| Dec 2010 | 2.4 | 5.9 |

| Calendar Year | ||

| 2011 | -3.5 | |

| 2010 | 16.4 | |

| 2009 | -21.9 | |

| 2008 | -3.4 |

Source: http://www.meti.go.jp/statistics/tyo/iip/result/pdf/press/h2a2001j.pdf

Japan’s machinery orders in Table VB-2 rose strongly in Jan after declining in Dec. Total orders grew 21.6 percent in Jan after falling 7.2 percent in Dec. Private-sector orders excluding volatile orders, which are closely watched, increased 3.4 percent in Jan 14.7 percent in Nov but fell 22.2 percent in Dec. Orders for manufacturing increased 4.7 in Jan after falling 7.1 percent in Dec but increasing 14.8 percent in Nov. Overseas orders jumped 20.1 percent in Jan. There is significant volatility in industrial orders in advanced economies.

Table VB-2, Japan, Machinery Orders, Month ∆%, SA

| 2011-2012 | Jan | Dec | Nov | Oct |

| Total | 21.6 | -7.2 | 14.7 | 3.2 |

| Private Sector | 4.6 | -22.2 | 21.5 | -9.2 |

| Excluding Volatile Orders | 3.4 | -7.1 | 14.8 | -6.9 |

| Mfg | -1.8 | -7.1 | 4.7 | 5.5 |

| Non Mfg ex Volatile | 2.3 | -6.0 | -6.2 | -7.3 |

| Government | -17.7 | 50.7 | -5.3 | 1.9 |

| From Overseas | 20.1 | 5.6 | 20.3 | 1.6 |

| Through Agencies | -2.5 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 4.0 |

Note: Mfg: manufacturing

Source: Japan Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/stat/juchu/1201juchu-e.html

Total orders for machinery and total private-sector orders excluding volatile orders for Japan are shown in Chart VB-1 of Japan’s Economic and Social Research Institute at the Cabinet Office. The trend of private-sector orders excluding volatile orders was increasing smoothly but may be flattening or even declining now even after the jump in Nov and increase in Jan. There could be reversal of the trend of increase in total orders. Fluctuations still prevent detecting longer term trends.

Chart VB-1, Japan, Machinery Orders

Source: Japan Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/stat/juchu/1201juchu-e.html

Table VB-3 provides values and percentage changes from a year earlier of Japan’s machinery orders without seasonal adjustment. Total orders of JPY 2,023,741 million are divided between JPY 1,102,168 overseas orders, or 54.5 percent of the total, and domestic orders of JPY 843,646, or 41.7 percent of the total, with orders through agencies of JPY 77,927 million, or 3.9 percent. Orders through agencies are not shown in the table because of the minor value. Twelve-month percentages changes in Jan 2012 were strong: 9.8 percent for total orders, 18.3 percent for overseas orders, 0.5 percent for domestic orders and 5.7 percent for private orders excluding volatile items. There is sharp reversal of 12-month percentage changes in Nov with increase of 11.0 percent in total orders, 8.0 percent in overseas orders, 13.5 percent in domestic orders and 12.5 percent in private orders excluding volatile items. The pace of increase declined in Dec with growth in 12 months of 0.8 percent for total orders, 12.6 percent for overseas orders, decline of 8.5 percent for domestic orders and growth of private orders excluding volatile items of 6.3 percent. There was strong impact from the global recession with total orders falling 23.3 percent in 2008, overseas orders dropping 29.4 percent and domestic orders decreasing 17.4 percent. Recovery was vigorous in 2010 with increase of total orders by 9.4 percent, overseas orders by 3.5 percent and domestic orders by 14.1 percent. The heavy impact of the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011 also affected machinery orders.

Table VB-3, Japan, Machinery Orders, 12 Months ∆% and Million Yen, Original Series

| Total | Overseas | Domestic | Private ex Volatile | |

| Value Jan 2012 | 2,023,741 | 1,102,168 | 843,646 | 591,468 |

| % Total | 100.0 | 54.5 | 41.7 | 29.2 |

| Value Jan 2011 | 1,842,807 | 931,632 | 839,129 | 559,691 |

| % Total | 100.0 | 50.6 | 45.5 | 30.3 |

| 12-month ∆% | ||||

| Jan 2012 | 9.8 | 18.3 | 0.5 | 5.7 |

| Dec 2011 | 0.8 | 12.6 | -8.5 | 6.3 |

| Nov 2011 | 11.0 | 8.0 | 13.5 | 12.5 |

| Oct 2011 | -6.8 | -15.6 | -1.0 | 1.5 |

| Dec 2010 | 9.4 | 3.5 | 14.1 | -0.6 |

| Dec 2009 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 3.6 | -1.9 |

| Dec 2008 | -23.3 | -29.4 | -17.4 | -24.7 |

| Dec 2007 | 1.3 | 9.8 | -4.3 | -6.4 |

| Dec 2006 | 0.8 | 0.9 | -0.1 | 0.1 |

Note: Total machinery orders = overseas + domestic demand + orders through agencies. Orders through agencies in Oct 2011 were JPY 88,919 million, or 5.4 percent of the total, and are not shown in the table. The data are the original numbers without any adjustments and differ from the seasonally-adjusted data.

Source: Japan Economic and Social Research Institute, Cabinet Office

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/stat/juchu/1201juchu-e.html

The tertiary activity index of Japan decreased 1.7 percent in Jan and increased 0.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan, as shown in Table VB-4. There was strong impact from the Tōhoku or Great East Earthquake and Tsunami of Mar 11, 2011 in the decline of the tertiary activity index by 5.9 percent in Mar and 3.1 percent in 12 months. The performance of the tertiary sector in the quarter Jul-Sep was weak: decline of 0.2 percent in Jul, increase of 0.1 percent in Aug and decline of 0.4 percent in Sep, after increasing 1.9 percent in Jun. The index has gained 5.3 percent in the ten months from Apr to Jan, almost erasing the loss in Mar of 5.9 percent or at the annual equivalent rate of 6.4 percent. Most of the growth occurred in the quarter from Apr to Jun with gain of 5.6 percent or at annual equivalent rate of 24.3 percent.

Table VB-4, Japan, Tertiary Activity Index, ∆%

| Month ∆% SA | 12 Months ∆% NSA | |

| Jan 2012 | -1.7 | 0.1 |

| Dec 2011 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| Nov | -0.6 | -0.5 |

| Oct | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Sep | -0.4 | 0.0 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Jul | -0.2 | -0.2 |

| Jun | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| May | 0.9 | -0.2 |

| Apr | 2.7 | -2.3 |

| Mar | -5.9 | -3.1 |

| Feb | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| Jan | -0.1 | 1.1 |

| Dec 2010 | -0.2 | 1.8 |

| Nov | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Sep | -0.4 | 1.3 |

| Aug | 0.1 | 2.3 |

| Jul | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Jun | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| May | -0.3 | 1.2 |

| Dec 2009 | -2.7 | |

| Dec 2008 | -3.3 | |

| Dec 2007 | -0.3 | |

| Dec 2006 | 0.6 | |

| Dec 2005 | 2.6 | |

| Dec 2004 | 1.6 | |

| Calendar Year | ||

| 2011 | -3.4 | |

| 2010 | 5.1 | |

| 2009 | 5.8 |

Source: http://www.meti.go.jp/statistics/tyo/sanzi/result/pdf/hv37903_201201j.pdf

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/statistics/tyo/sanzi/index.html

Month and 12-month rates of growth of the tertiary activity index of Japan and components in Jan are provided in Table VB-5. Electricity, gas, heat supply and water increased 1.3 percent in Jan but fell 3.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan. Wholesale and retail trade decreased 1.5 percent in the month of Jan and fell 1.2 percent in 12 months. Information and communications fell 1.5 percent in Dec but grew 0.8 percent in 12 months.

Table VB-5, Japan, Tertiary Index and Components, Month and 12-Month Percentage Changes ∆%

| Dec 2011 | Weight | Month ∆% SA | 12 Months ∆% NSA |

| Tertiary Index | 10,000.0 | -1.7 | 0.1 |

| Electricity, Gas, Heat Supply & Water | 372.9 | 1.3 | -3.1 |

| Information & Communications | 951.2 | -1.2 | 0.8 |

| Wholesale & Retail Trade | 2,641.2 | -1.5 | -1.2 |

| Finance & Insurance | 971.1 | -6.8 | -0.2 |

| Real Estate & Goods Rental & Leasing | 903.4 | -0.6 | -0.9 |

| Scientific Research, Professional & Technical Services | 551.3 | -1.8 | 0.6 |

| Accommodations, Eating, Drinking | 496.0 | -2.0 | 0.7 |

| Living-Related, Personal, Amusement Services | 552.7 | -1.2 | 1.2 |

| Learning Support | 116.9 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Medical, Health Care, Welfare | 921,1 | -0.8 | 2.0 |

| Miscellaneous ex Government | 626.7 | 0.2 | 3.0 |

Source: http://www.meti.go.jp/statistics/tyo/sanzi/result/pdf/hv37903_201201j.pdf

http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/en/sna/sokuhou/qe/main_1e.pdf

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/statistics/tyo/sanzi/index.html

VC. China. The HSBC Composite Output Index for China, compiled by Markit, registered an increase from 49.7 in Jan to 51.8 in Feb, suggesting improving private-sector business activity (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9262). Growth of services compensated weakness of manufacturing. Hongbin Qu, Chief Economist, China & Co-Head of Asian Economic Research at HSBC, finds that increases in new orders drove the increase in services but that the combination with manufacturing deceleration because of weak external orders can result in growth of only 8 percent in IQ2012 GDP until further easing permeates throughout the economy (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9262). Table CNY provides the country table for China.

Table CNY, China, Economic Indicators

| Price Indexes for Industry | Feb 12 months ∆%: 0.0 Feb month ∆%: 0.1 |

| Consumer Price Index | Feb month ∆%: -0.1 Feb 12 month ∆%: 3.2 |

| Value Added of Industry | Feb month ∆%: 0.98 Jan-Feb 2012/Jan-Feb 2011 ∆%: 11.4 |

| GDP Growth Rate | Year IVQ2011 ∆%: 8.9 |

| Investment in Fixed Assets | Total Jan-Feb 2012 ∆%: 21.5 Jan-Dec ∆% real estate development: 27.8 |

| Retail Sales | Jan month ∆%: 1.6 Jan-Feb ∆%: 14.7 |

| Trade Balance | Feb balance minus $31.48 billion Cumulative Feb: $4.2 billion |

Links to blog comments in Table CNY:

03/11/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/thirty-million-unemployed-or_11.html

01/22/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/01/world-inflation-waves-united-states.html

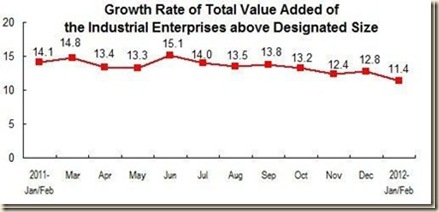

Cumulative and 12-months rates of value added of industry in China are provided in Table VC-1. Value added in total industry in 2011 increased 13.9 percent relative to a year earlier and 12.8 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec. In Jan-Feb 2012, industry increased 11.4 percent relative to Jan-Feb 2011. Heavy industry is the driver of growth with a cumulative rate of 12.7 percent relative to a year earlier. Growth has decelerated from cumulative 14.1 percent in Jan-Feb 2011.

Table VC-1, China, Growth Rate of Value Added of Industry ∆%

| Industry | Light Industry | Heavy | State | Private | |

| 2012 | |||||

| Jan-Feb | 11.4 | 12.7 | 10.9 | 7.3 | 13.9 |

| 12 M Dec | 12.8 | 12.6 | 13.0 | 9.2 | 14.7 |

| Jan-Dec | 13.9 | 13.0 | 14.3 | 9.9 | 15.8 |

| 12 M Nov | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 7.8 | 14.4 |

| Jan-Nov | 14.0 | 13.0 | 14.4 | 9.9 | 16.0 |

| 12 M Oct | 13.2 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 8.9 | 15.1 |

| Jan-Oct | 14.1 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 10.1 | 9.1 |

| 12 M Sep | 13.8 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 9.9 | 16.0 |

| Jan-Sep | 14.2 | 13.1 | 14.6 | 10.4 | 16.1 |

| 12 M Aug | 13.5 | 13.4 | 13.5 | 9.4 | 15.5 |

| Jan-Aug | 14.2 | 13.1 | 14.6 | 10.4 | 16.1 |

| 12 M | 14.0 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 9.5 | |

| Jan-Jul | 14.3 | ||||

| 12 M | 15.1 | 13.9 | 15.6 | 10.7 | 20.8 |

| Jan-Jun | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.7 | 10.7 | 19.7 |

| 12 M May | 13.3 | 12.9 | 13.5 | 8.9 | 18.7 |

| Jan-May | 14.0 | 12.9 | 14.4 | 10.7 | 19.3 |

| 12 M Apr | 13.4 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 10.4 | 18.0 |

| Jan-Apr | 14.2 | 12.9 | 14.7 | 11.2 | 19.5 |

| 12 M Mar | 14.8 | 12.8 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 19.2 |

| Jan-Mar | 14.4 | 13.1 | 14.9 | 11.4 | 19.8 |

| 12 M Feb | 14.9 | 13.1 | 15.6 | 10.5 | 21.7 |

| Jan-Feb | 14.1 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 10.6 | 20.3 |

Source: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402791971.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20120117_402779577.htmhttp://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111212_402771586.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111110_402765073.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111018_402759844.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110909_402753263.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110810_402746176.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/statisticaldata/index.htm

Chart VC-1 provides cumulative growth rates of value added of industry in 2011 and Jan-Feb 2012. Growth rates of value added of industry in the first five months of 2010 were higher than in 2011 as would be expected in an earlier phase of recovery from the global recession. Growth rates have converged in the second half of 2011 to lower percentages.

Chart VC-1, China, Growth Rate of Total Value Added of Industry, Cumulative Year-on-Year ∆%

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402791971.htm

Yearly rates of growth for the past 12 months and cumulative relative to the earlier year of various segments of industrial production in China are provided in Table VC-2. Rates for Jan-Dec 2011 relative to the same period a year earlier fluctuated but remained above 10 percent with the exception of motor vehicles and crude oil. There is deceleration in Dec of the 12-month rates of change with only nonferrous metals at 13.2 percent exceeding 10 percent. Further deceleration is evident in Jan-Feb with all rates below 10 percent.

Table VC-2, China, Industrial Production Operation ∆%

| Elec- | Pig Iron | Cement | Crude | Non- | Motor Vehicles | |

| 2012 | ||||||

| Jan-Feb | 7.1 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 8.4 | -1.8 |

| 2011 | ||||||

| 12 M Dec | 9.7 | 3.7 | 7.0 | 4.0 | 13.2 | -6.5 |

| Jan-Dec | 12.0 | 8.4 | 16.1 | 4.9 | 10.6 | 3.0 |

| 12 M Nov | 8.5 | 7.8 | 11.2 | 3.2 | 8.2 | -1.3 |

| Jan-Nov | 12.0 | 13.1 | 17.2 | 5.3 | 10.2 | 3.9 |

| 12 M | 9.3 | 13.4 | 16.5 | -0.9 | 3.7 | 1.3 |

| Jan-Oct | 12.3 | 13.7 | 18.0 | 5.4 | 10.4 | 5.2 |

| 12 M Sep | 11.5 | 18.8 | 15.7 | 1.5 | 13.9 | 2.5 |

| Jan-Sep | 12.7 | 13.9 | 18.1 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 5.5 |

| 12 M Aug | 10.0 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 4.5 | 15.6 | 9.5 |

| Jan-Aug | 13.0 | 13.1 | 18.4 | 6.6 | 4.7 | |

| 12 M | 13.2 | 14.9 | 16.8 | 5.9 | 9.8 | -1.3 |

| Jan-Jul | 13.3 | 13.0 | 19.2 | 6.9 | 9.9 | 4.0 |

| 12 M | 16.2 | 14.8 | 19.9 | -0.7 | 9.8 | 3.6 |

| 12 M | 12.1 | 10.6 | 19.2 | 6.0 | 14.2 | -1.9 |

| 12 M Apr | 11.7 | 8.3 | 22.4 | 6.8 | 6.1 | -1.6 |

| 12 M Mar | 14.8 | 13.7 | 29.8 | 8.0 | 11.6 | 9.9 |

| 12 M Feb | 11.7 | 14.5 | 9.1 | 10.9 | 14.4 | 10.3 |

| 12 M Jan | 5.1 | 3.5 | 16.4 | 12.2 | 1.4 | 23.9 |

| 12 M Dec 2010 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 17.3 | 10.3 | -1.9 | 27.6 |

M: month

Source: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402791971.htmhttp://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20120117_402779577.htmhttp://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111212_402771586.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111110_402765073.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111018_402759844.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110810_402746176.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110909_402753263.htm

Monthly growth rates of industrial production in China are provided in Table VC-6. Monthly rates have fluctuated around 1 percent. Jan and Feb 2012 are somewhat weaker.

Table VC-3, China, Industrial Production Operation, Month ∆%

| 2011 | Month ∆% |

| Feb | 0.98 |

| Mar | 1.08 |

| Apr | 0.87 |

| May | 0.88 |

| Jun | 1.25 |

| Jul | 0.71 |

| Aug | 0.79 |

| Sep | 0.96 |

| Oct | 0.70 |

| Nov | 0.69 |

| Dec | 0.94 |

| Jan 2012 | 0.38 |

| Feb | 0.70 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402791971.htm

Table VC-4 provides cumulative growth of investment in fixed assets in China in 2011 relative to 2010 and in Jan-Feb 2012 relative to a year earlier. Total fixed investment has grown at a high rate fluctuating around 25 percent and fixed investment in real estate development has grown at rates in excess of 30 percent. In Jan-Dec investment in fixed assets in China grew 23.8 percent relative to a year earlier and 27.9 percent in real estate development. There was slight deceleration in the final two months of 2011 that continued into Jan-Feb 2012.

Table VC-4, China, Investment in Fixed Assets ∆% Relative to a Year Earlier

| Total | State | Real Estate Development | |

| Jan-Feb 2012 | 21.5 | 8.8 | 27.9 |

| Jan-Dec 2011 | 23.8 | 11.1 | 27.9 |

| Jan-Nov | 24.5 | 11.7 | 29.9 |

| Jan-Oct | 24.9 | 12.4 | 31.1 |

| Jan-Sep | 24.9 | 12.7 | 32.0 |

| Jan-Aug | 25.0 | 12.1 | 33.2 |

| Jan-Jul | 25.4 | 13.6 | 33.6 |

| Jan-Jun | 25.6 | 14.6 | 32.9 |

| Jan-May | 25.8 | 14.9 | 34.6 |

| Jan-Apr | 25.4 | 16.6 | 34.3 |

| Jan-Mar | 25.0 | 17.0 | 34.1 |

| Jan-Feb | 24.9 | 15.6 | 35.2 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120312_402791525.htm

Chart VC-2 provides cumulative fixed asset investment in China relative to a year earlier. Growth rose to 25.8 percent in Jan-May and then fell back to 24.9 percent in Sep and Oct, declining further to 24.5 percent in Nov and 23.8 percent in Dec with deeper drop in Jan-Feb to 21.5 percent.

Chart VC-2, China, Investment in Fixed Assets, ∆% Cumulative over Year Earlier

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120312_402791525.htm

Monetary policy has been used in China in the form of increases in interest rates and required reserves of banks to moderate real estate investment. These policies have been reversed because of lower inflation and weakening economic growth. Chart VC-3 shows decline of fluctuating cumulative growth rates of investment in real estate development relative to a year earlier from 35.2 percent in Jan-Feb to 31.1 percent in Jan-Oct, 29.9 percent in Jan Nov, and 27.9 percent in both Jan-Dec 2011 and Jan-Feb 2012.

Chart VC-3, China, Investment in Real Estate Development, ∆% Cumulative over Year Earlier

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402792043.htm

Table VC-5 provides monthly growth rates of investment in fixed assets in China from Feb 2011 to Feb 2012. Growth rates have moderated from Nov 2011 to Feb 2012.

Table VC-5, China, Investment in Fixed Assets, Month ∆%

| Month ∆% | |

| Feb 2011 | 0.58 |

| Mar | 1.96 |

| Apr | 1.87 |

| May | 1.83 |

| Jun | 1.39 |

| Jul | 1.66 |

| Aug | 1.40 |

| Sep | 2.02 |

| Oct | 1.86 |

| Nov | 1.04 |

| Dec | 1.17 |

| Jan 2012 | 1.08 |

| Feb 2012 | 1.61 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120312_402791525.htm

Growth rates of retail sales in China monthly, 12 months and cumulative relative to a year earlier are in Table VC-6. There is still insufficient data to assess if the decline of growth rates to cumulative 14.7 percent in Feb 2012 constitutes the beginning of a downward trend

Table VC-6, China, Total Retail Sales of Consumer Goods ∆%

| Month ∆% | 12 Months ∆% | Cumulative ∆%/ | |

| 2012 | |||

| Feb | 1.6 | 14.7 | |

| Jan | 1.0 | ||

| 2011 | |||

| Dec | 1.41 | 18.1 | 17.1 |

| Nov | 1.28 | 17.3 | 17.0 |

| Oct | 1.30 | 17.2 | 17.0 |

| Sep | 1.35 | 17.7 | 17.0 |

| Aug | 1.29 | 17.0 | 16.9 |

| Jul | 1.30 | 17.2 | 16.8 |

| Jun | 1.40 | 17.7 | 16.8 |

| May | 1.31 | 16.9 | 16.6 |

| Apr | 1.33 | 17.1 | 16.5 |

| Mar | 1.35 | 17.4 | 17.4 |

| Feb | 1.30 | 11.6 | 15.8 |

| Jan | 19.9 | 19.9 |

Note: there are slight revisions of month relative to earlier month data but not of the month on the same month year earlier or cumulative relative to cumulative year earlier in the databank

Source: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402792035.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20120117_402779577.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111209_402771402.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111110_402765083.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110810_402746163.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/statisticaldata/index.htm

Chart VC-4 of the National Bureau of Statistics of China provides 12-month rates of growth of retail sales in 2011. There is again a drop into 2012 with the lowest percentage in Chart VC-4.

Chart VC-4, China, Total Retail Sales of Consumer Goods 12 Months ∆%

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402792035.htm

Table VC-7 provides monthly percentage changes of retail sales in China. Although the rate of 1.02 percent in Jan is the lowest in Table VC-7, the rate of 1.56 percent in Feb is the highest. Seasonal effects of the New Year have been affecting China’s data.

Table VC-7, Retail Sales, Month ∆%

| 2011 | Month ∆% |

| Feb | 1.35 |

| Mar | 1.35 |

| Apr | 1.33 |

| May | 1.29 |

| Jun | 1.43 |

| Jul | 1.28 |

| Aug | 1.34 |

| Sep | 1.37 |

| Oct | 1.34 |

| Nov | 1.29 |

| Dec | 1.45 |

| 2012 | |

| Jan | 1.02 |

| Feb | 1.56 |

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20120313_402792035.htm

Table VC-8 provides China’s exports, imports, trade balance and percentage changes from Dec 2010 to Feb 2012. Exports fell 0.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan while imports fell 15.3 percent for a still sizeable trade surplus of $27.28 billion. In Feb, exports increased 18.4 percent while imports jumped 39.6 percent for a sizeable deficit of $31.48 billion. There are distortions from the New Year holidays.

Table VC-8, China, Exports, Imports and Trade Balance USD Billion and ∆%

| Exports | ∆% Relative | Imports USD | ∆% Relative | Balance | |

| Feb 2012 | 114.47 | 18.4 | 145.96 | 39.6 | -31.48 |

| Jan 2012 | 149.94 | -0.5 | 122.66 | -15.3 | 27.28 |

| Dec 2011 | 174.72 | 13.4 | 158.20 | 11.8 | 16.52 |

| Nov | 174.46 | 13.8 | 159.94 | 22.1 | 14.53 |

| Oct | 157.49 | 15.9 | 140.46 | 28.7 | 17.03 |

| Sep | 169.67 | 17.1 | 155.16 | 20.9 | 14.51 |

| Aug | 173.32 | 24.5 | 155.56 | 30.2 | 17.76 |

| Jul | 175.13 | 20.4 | 143.64 | 22.9 | 31.48 |

| Jun | 161.98 | 17.9 | 139.71 | 19.3 | 22.27 |

| May | 157.16 | 19.4 | 144.11 | 28.4 | 13.05 |

| Apr | 155.69 | 29.9 | 144.26 | 21.8 | 11.42 |

| Mar | 152.20 | 35.8 | 152.06 | 27.3 | 0.14 |

| Feb | 96.74 | 2.4 | 104.04 | 19.4 | -7.31 |

| Jan | 150.73 | 37.7 | 144.27 | 51.0 | 6.46 |

| Dec 2010 | 154.15 | 17.9 | 141.07 | 25.6 | 13.08 |

Source:

http://english.customs.gov.cn/publish/portal191/

http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/static/column/statistic/BriefStatistics.html/1

Table VC-9 provides cumulative exports, imports and the trade balance of China together with percentage growth of exports and imports. The trade balance in 2011 of $155.14 billion is lower than those from 2008 to 2010. There is a rare cumulative deficit of $4.2 billion in Feb 2012. More observations are required to detect trends of Chinese trade.

Table VC-9, China, Year to Date Exports, Imports and Trade Balance USD Billion and ∆%

| Exports | ∆% Relative | Imports USD | ∆% Relative | Balance | |

| Feb 2012 | 264.41 | 6.8 | 268.22 | 8.0 | -4.2 |

| Jan | 149.94 | -0.5 | 122.66 | -15.3 | 27.28 |

| Dec 2011 | 1,898.60 | 20.3 | 1,743.46 | 24.9 | 155.14 |

| Nov | 1,724.01 | 21.1 | 1585.61 | 26.4 | 138.40 |

| Oct | 1,549.71 | 22.0 | 1,425.68 | 26.9 | 124.03 |

| Sep | 1,392.27 | 22.7 | 1,285.17 | 26.7 | 107.10 |

| Aug | 1,222.63 | 23.6 | 1,129.90 | 27.5 | 92.73 |

| Jul | 1,049.38 | 23.4 | 973.17 | 26.9 | 76.21 |

| Jun | 874.3 | 24.0 | 829.37 | 27.6 | 44.93 |

| May | 712.37 | 25.5 | 689.41 | 29.4 | 22.96 |

| Apr | 555.30 | 27.4 | 545.02 | 29.6 | 10.28 |

| Mar | 399.64 | 26.5 | 400.66 | 32.6 | -1.02 |

| Feb | 247.47 | 21.3 | 248.36 | 36.0 | -0.89 |

| Jan | 150.7 | 37.7 | 144.27 | 51.0 | 6.46 |

| Dec 2010 | 1577.93 | 31.3 | 1394.83 | 38.7 | 183.10 |

Source:

http://english.customs.gov.cn/publish/portal191/

http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/static/column/statistic/BriefStatistics.html/1

VC Euro Area. The Markit Eurozone PMI® Composite Output Index declined to 49.3 in Feb from 50.4 in Jan, which is the first reading above the contraction zone at 50.0 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9242). The index suggests decline of business activity during four month, expansion in Jan and then contraction in Feb. Chris Williamson, Chief Economist at Markit, finds that economic activity could have contracted 0.1 percent in IQ2012 (http://www.markiteconomics.com/MarkitFiles/Pages/ViewPressRelease.aspx?ID=9242). Table EUR provides the country economic indicators for the euro area.

Table EUR, Euro Area Economic Indicators

| GDP | IVQ2011 ∆% minus 0.3; IVQ2011/IVQ2010 ∆% 0.7 Blog 03/11/12 |

| Unemployment | Jan 2012: 10.7% unemployment rate Jan 2012: 16.925 million unemployed Blog 03/04/12 |

| HICP | Feb month ∆%: 0.5 12 months Feb ∆%: 2.7 |

| Producer Prices | Euro Zone industrial producer prices Jan ∆%: 0.7 |

| Industrial Production | Jan month ∆%: 0.2 Jan 12 months ∆%: -1.2 |

| Industrial New Orders | Dec month ∆%: 1.9 Oct 12 months ∆%: minus 1.7 |

| Construction Output | Dec month ∆%: 0.3 |

| Retail Sales | Jan month ∆%: 0.3 |

| Confidence and Economic Sentiment Indicator | Sentiment 93.9 Feb 2012 down from 107 in Dec 2010 Confidence minus 20.1 Jan 2012 down from minus 11 in Dec 2010 Blog 03/04/12 |

| Trade | Jan-Dec 2011/2010 Exports ∆%: 12.7 Jan 2012 12-month Exports ∆% 10.9 Imports ∆% 3.6 |

| HICP, Rate of Unemployment and GDP | Historical from 1999 to 2011 Blog 3/18/12 |

Links to blog comments in Table EUR:

03/11/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/thirty-million-unemployed-or_11.html

03/04/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/mediocre-economic-growth-flattening_04.html

02/26/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/decline-of-united-states-new-house_26.html

02/19/12 http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/world-inflation-waves-united-states_19.html

Industrial production in the euro area declined in three of five months from Sep 2011 to Jan 2012, as shown in Table VD-1 with revised estimates by EUROSTAT. Production fell cumulatively 3.8 percent in Sep-Jan or at the annual equivalent rate of decline of 8.8 percent. All segments of industrial production fell in Dec but all increased in Jan with exception of nondurable goods. Production of capital goods fell 3.7 percent in Sep, increasing in all subsequent months with exception of decline of 1.2 percent in Dec but fell cumulatively 3.1 percent in Sep to Jan or at the annual equivalent rate of 7.4 percent. Industrial production is highly volatile in larger economies in the euro zone.

Table VD-1, Euro Zone, Industrial Production Month ∆%

| Total | INT | ENE | CG | DUR | NDUR | |

| Jan 2012 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | -0.7 |

| Dec 2011 | -1.1 | -1.1 | -2.6 | -1.2 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| Nov | -0.4 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -1.6 |

| Oct | 0.1 | -0.6 | -0.9 | 0.9 | -1.1 | 0.7 |

| Sep | -2.6 | -1.9 | -1.9 | -3.7 | -3.8 | -1.4 |

| Aug | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.4 | -2.3 | 1.4 |

Notes: INT: Intermediate; ENE: Energy; CG: Capital Goods; DUR: Durable Consumer Goods; NDUR: Nondurable Consumer Goods

Source: Eurostat

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/4-14032012-AP/EN/4-14032012-AP-EN.PDF

Table VD-2 provides 12-month percentage changes of industrial production and major industrial categories in the euro zone. Industrial production decreased 1.2 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan. There is only positive 12-month growth of 3.1 percent for capital goods.

Table VD-2, Euro Zone, Industrial Production 12-Month ∆%

| 2012 | Jan Month ∆% | Jan 12-Month ∆% |

| Total | 0.2 | -1.2 |

| Intermediate Goods | 0.2 | -1.3 |

| Energy | 1.4 | -6.2 |

| Capital Goods | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| Durable Consumer Goods | 0.1 | -2.2 |

| Nondurable Consumer Goods | -0.7 | -1.8 |

Source: Eurostat

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/4-14032012-AP/EN/4-14032012-AP-EN.PDF

There has been significant decline in percentage changes of industrial production and major categories in 12-month rates throughout 2011 as shown in Table VD-3. The 12-month rate of growth in Aug of 5.9 percent has fallen to minus 1.2 percent in Jan. Trend is difficult to identify because of significant volatility. Capital goods were growing at 13.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Aug and only at 3.1 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan.

Table VD-3, Euro Zone, Industrial Production 12-Month ∆%

| Total | INT | ENE | CG | DUR | NDUR | |

| Jan 2012 | -1.2 | -1.3 | -6.2 | 3.1 | -2.2 | -1.8 |

| Dec 2011 | -1.8 | 0.0 | -13.0 | 2.0 | -3.3 | -0.5 |

| Nov | 0.2 | -0.1 | -6.4 | 4.9 | -3.1 | -1.3 |

| Oct | 1.0 | 0.3 | -5.0 | 4.9 | -3.1 | 0.8 |

| Sep | 2.2 | 2.2 | -3.4 | 6.0 | -0.9 | 0.3 |

| Aug | 5.9 | 5.3 | -2.2 | 13.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

Notes: INT: Intermediate; ENE: Energy; CG: Capital Goods; DUR: Durable Consumer Goods; NDUR: Nondurable Consumer Goods

Source: Eurostat

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/4-14032012-AP/EN/4-14032012-AP-EN.PDF

Blanchard (2011WEOSep) analyzes the difficulty of fiscal consolidation efforts during periods of weak economic growth. Table VD-4 provides monthly and 12-month percentage changes of industrial production in the euro zone for various members and the UK, which is not a member. There is improvement in month and 12-month percentage changes in Jan 2012 with 0.2 percent for the euro zone as a whole but decline of 1.2 percent in 12 months. Germany’s industrial production increased 1.5 percent in Jan and France’s industrial production increased 0.4 percent. There is mixed performance across members.

Table VD-4, Euro Zone, Industrial Production, Month and 12-Month ∆%

| Month ∆% Jan 2012 | Month ∆% Dec 2011 | 12 Months ∆% Jan 2012 | 12 Months ∆% Dec 2011 | |

| Euro Zone | 0.2 | -1.1 | -1.2 | -1.8 |

| Germany | 1.5 | -2.2 | 1.6 | -0.3 |

| France | 0.4 | -1.3 | -2.2 | -2.1 |

| Netherlands | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Finland | 2.0 | 1.1 | -6.0 | 1.6 |

| Belgium | NA | -2.9 | NA | 1.5 |

| Portugal | 1.2 | -1.1 | -9.0 | -4.0 |

| Ireland | 0.7 | 2.6 | -0.4 | -3.9 |

| Italy | -2.5 | 1.2 | -5.0 | -1.8 |

| Greece | 2.3 | -2.1 | -13.5 | -5.2 |

| Spain | -0.2 | 1.0 | -4.2 | -3.5 |

| UK | -0.4 | 0.4 | -4.4 | -2.3 |

Source: Eurostat http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/4-14032012-AP/EN/4-14032012-AP-EN.PDF

Euro zone trade growth continues to be strong as shown in Table VD-5. Exports grew at 12.7 percent and imports at 12.2 percent in Jan-Dec 2011 relative to Jan-Dec 2010. The 12-month rates of growth of exports were 10.9 percent in Jan 2012 while imports increased 3.6 percent. At the margin, rates of growth of trade are declining in part because of moderation of commodity prices.

Table VD-5, Euro Zone, Exports, Imports and Trade Balance, Billions of Euros and Percent, NSA

| Exports | Imports | |

| Jan-Dec 2011 | 1732.6 | 1742.4 |

| Jan-Dec 2010 | 1537.3 | 1552.0 |

| ∆% | 12.7 | 12.3 |

| Jan 2012 | 138.4 | 146.0 |

| Jan 2011 | 124.8 | 140.9 |

| ∆% | 10.9 | 3.6 |

| Dec 2011 | 146.9 | 137.8 |

| Dec 2010 | 134.9 | 136.6 |

| ∆% | 8.9 | 0.9 |

| Trade Balance | Jan 2012 | Jan 2011 |

| € Billions | -16.1 | -7.6 |

Source: EUROSTAT http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/6-16032012-AP/EN/6-16032012-AP-EN.PDF

The structure of trade of the euro zone in Jan-Dec 2011 is provided in Table VD-6. Data are still not available for trade structure for Jan 2012. Manufactured exports grew 11.4 percent in Jan-Dec 2011 relative to Jan-Dec 2010 while imports grew 8.6 percent. The trade surplus in manufactured products was lower than the trade deficit in primary products in both Jan-Dec 2011 and Jan-Dec 2010.

Table VD-6, Euro Zone, Structure of Exports, Imports and Trade Balance, € Billions, ∆%

| Primary | Manufactured | Other | Total | |

| Exports | ||||

| Jan-Dec 2011 € B | 260.9 | 1422.5 | 49.1 | 1732.6 |

| Jan-Dec 2010 € B | 215.2 | 1276.9 | 45.2 | 1537.3 |

| ∆% | 21.2 | 11.4 | 8.6 | 12.7 |

| Imports | ||||

| Jan-Dec 2011 € B | 617.7 | 1095.3 | 29.4 | 1742.4 |

| Jan-Dec 2010 € B | 501.2 | 1021.8 | 29.0 | 1552.0 |

| ∆% | 23.2 | 7.2 | 1.4 | 12.3 |

| Trade Balance € B | ||||

| Jan-Dec 2011 | -356.7 | 327.2 | 19.7 | -9.8 |

| Jan-Dec 2010 | -285.9 | 255.1 | 16.2 | -14.7 |

Source: EUROSTAT http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/6-16032012-AP/EN/6-16032012-AP-EN.PDF