Financial Risk Aversion and Collapse of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets, World Financial Turbulence, Global Inflation and World Economic Slowdown

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011

Executive Summary

I Financial Risk Aversion and Collapse of Valuations of Risk Financial Assets

IA Unconventional Monetary Policy

IB Financial Risk Aversion

IC Financial Risk Valuations

ID Global Inflation Waves

IE Summary

IF Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy

IFi Theory

IFii Policy

IFiii Evidence

IFiv Unwinding Strategy

II World Financial Turbulence

IIIA Financial Risks

IIB Fiscal Compact

IIC European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort

IID Euro Zone Survival Risk

IIE Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation

III Global Inflation

IV World Economic Slowdown

IVA United States

IVB Japan

IVC China

IVD Euro Area

IVE Germany

IVF France

IVG Italy

IVH United Kingdom

V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VI Economic Indicators

VII Interest Rates

VIII Conclusion

References

Appendix I The Great Inflation

Executive Summary

The critical fact of current world financial markets is the combination of “unconventional” monetary policy with intermittent shocks of financial risk aversion. There are two interrelated unconventional monetary policies. First, unconventional monetary policy consists of (1) reducing short-term policy interest rates toward the “zero bound” such as fixing the fed funds rate at 0 to ¼ percent by decision of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) since Dec 16, 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm). Second, unconventional monetary policy also includes a battery of measures to also reduce long-term interest rates of government securities and asset-backed securities such as mortgage-backed securities.

When inflation is low, the central bank lowers interest rates to stimulate aggregate demand in the economy, which consists of consumption and investment. When inflation is subdued and unemployment high, monetary policy would lower interest rates to stimulate aggregate demand, reducing unemployment. When interest rates decline to zero, unconventional monetary policy would consist of policies such as large-scale purchases of long-term securities to lower their yields. A major portion of credit in the economy is financed with long-term asset-backed securities. Loans for purchasing houses, automobiles and other consumer products are bundled in securities that in turn are sold to investors. Corporations borrow funds for investment by issuing corporate bonds. Loans to small businesses are also financed by bundling them in long-term bonds. Securities markets bridge the needs of higher returns by savers obtaining funds from investors that are channeled to consumers and business for consumption and investment. Lowering the yields of these long-term bonds could lower costs of financing purchases of consumer durables and investment by business. The essential mechanism of transmission from lower interest rates to increases in aggregate demand is portfolio rebalancing. Withdrawal of bonds in a specific maturity segment or directly in a bond category such as currently mortgage-backed securities causes reductions in yield that are equivalent to increases in the prices of the bonds. There can be secondary increases in purchases of those bonds in private portfolios in pursuit of their increasing prices. Lower yields translate into lower costs of buying homes and consumer durables such as automobiles and also lower costs of investment for business. There are two additional intended routes of transmission. (1) Unconventional monetary policy or its expectation can increase stock market valuations (Bernanke 2010WP). Increases in equities traded in stock markets can increase the wealth of consumers inducing increases in consumption. (2) Unconventional monetary policy causes devaluation of the dollar relative to other currencies than can cause increases in net exports of the US that increase aggregate economic activity (Yellen 2011AS).

Monetary policy can lower short-term interest rates quite effectively. Lowering long-term yields is somewhat more difficult. The critical issue is that monetary policy cannot ensure that increasing credit at low interest cost increases consumption and investment. There is a large variety of possible allocation of funds at low interest rates from consumption and investment to multiple risk financial assets. Monetary policy does not control how investors will allocate asset categories. A critical financial practice is to borrow at low short-term interest rates to invest in high-risk, leveraged financial assets. Investors may increase in their portfolios asset categories such as equities, emerging market equities, high-yield bonds, currencies, commodity futures and options and multiple other risk financial assets including structured products. If there is risk appetite, the carry trade from zero interest rates to risk financial assets will consist of short positions at short-term interest rates (or borrowing) and short dollar assets with simultaneous long positions in high-risk, leveraged financial assets such as equities, commodities and high-yield bonds. Low interest rates may induce increases in valuations of risk financial assets that may fluctuate in accordance with perceptions of risk aversion by investors and the public. During periods of muted risk aversion, carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in risk financial assets cause temporary waves of inflation that may foster instead of preventing financial stability. During periods of risk aversion such as fears of disruption of world financial markets and the global economy resulting from collapse of the European Monetary Union, carry trades are unwound with sharp deterioration of valuations of risk financial assets.

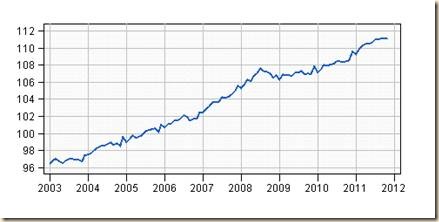

McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1974) argue that legal restrictions on financial institutions can be detrimental to economic development. “Financial repression” is the term used in the economic literature for these restrictions (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 81-6). Interest rate ceilings on deposits and loans have been commonly used. Chart ES1 provides savings as percent of disposable income or the US savings rate. There was a long-term downward sloping trend from 12 percent in the early 1980s to less than 2 percent in 2005-2006. The savings rate then rose during the contraction and also in the expansion. In 2011 the savings rate declined as consumption is financed with savings in part because of the disincentive or frustration of receiving a few pennies for every $10,000 of deposits in a bank. The objective of monetary policy is to reduce borrowing rates to induce consumption but it has collateral disincentive of reducing savings. The zero interest rate of monetary policy is a tax on saving. This tax is highly regressive, meaning that it affects the most people with lower income or wealth and retirees. The long-term decline of savings rates in the US has created a dependence on foreign savings to finance the deficits in the federal budget and the balance of payments. Financial repression also disrupts portfolio management and asset/liability management such as, for example, choosing assets to match benefits and income in pension funds and actually all management of financial institutions. Functions of finance such as allocating savings to long-term sound projects (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a) 30-42, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 37-44, 45-60) can be frustrated, constraining the volume of financial intermediation required for economic growth.

Chart ES1, US, Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Personal Income, Quarterly, 1980-2011

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

The most critical source of risk aversion in international financial markets is the fear of unfavorable unwinding of the debt crisis in Europe. Section II World Financial Turbulence analyzes in detail the euro zone debt crisis. Fears originating in the euro zone debt crisis dominate wide oscillations in equity and bond markets that are transmitted worldwide.

Another major concern is the weakness of the expansion phase beginning in IIIQ2009 after the global recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Advanced economies are growing slowly with high levels of unemployment as followed in this blog in Section IV World Economic Slowdown.

Risk aversion is manifested in withdrawal of investments from financial assets to assets in currencies and government obligations of countries that are immune from risk at least in the medium term. Investment funds seeking refuge from risk are channeled to the US dollar, Japanese yen and Swiss franc. Government obligations such as US Treasury securities and German government securities are favored relative to higher risks in equities and fixed-income. When risk appetite returns, funds flow away from safe havens toward higher risks, depreciating the dollar and increasing valuations of risk financial assets.

Zero interest rates induce carry trades that magnify valuations of risk financial assets in the absence of risk aversion. In the presence of risk aversion, cheap money flows to the safety of the dollar, Japanese yen and Swiss franc and the government obligations of the United States and Germany.

Percentage changes of risk financial assets from the last day of the year relative to the last day of the earlier year are provided in Table ES1 from 2007 to 2011. The only gain for a major equity market in Table ES1 for 2011 is 5.5 percent for the DJIA. S&P 500 is better than other equity markets by remaining flat for 2011. With the exception of a drop of 8.4 percent of the European equity index STOXX 50, all declines of equity markets are in excess of 10 percent. China’s Shanghai Composite lost 21.7 percent. The equity index of Germany Dax fell 14.7 percent. The DJ UBS Commodities Index dropped 13.4 percent. Robin Wigglesworth, writing on Dec 30, 2011, on “$6.3tn wiped off markets in 2011,” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/483069d8-32f3-11e1-8e0d-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1i2BE7OPa

), provides an estimate of $6.3 trillion erased from equity markets globally in 2011. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO2011Aug, 90) estimates US nominal GDP in 2011 at $15,238 billion. The loss in equity markets worldwide in 2011 of $6.3 trillion is equivalent to about 41 percent of US GDP or economic activity in 2011. Table ES1 also provides the exchange rate of number of US dollars (USD) required in buying a unit of euro (EUR), USD/EUR. The dollar appreciated 3.2 percent on the last day of trading in 2011 relative to the last day of trading in 2010.

Table ES1, Percentage Change of Year-end Values of Financial Assets Relative to Earlier Year-end Values 2007-2010

| 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | |

| DJIA | 5.5 | 11.0 | 18.8 | -33.8 | 6.1 |

| S&P 500 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 23.5 | -38.5 | 3.1 |

| NYSE Fin | -18.1 | 5.0 | 22.7 | -53.6 | -13.5 |

| Dow Global | -13.7 | 4.6 | 30.8 | -45.5 | 30.9 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -17.6 | 15.9 | 36.4 | -44.2 | 14.2 |

| Nikkei Av | -17.3 | -3.0 | 20.6 | -42.9 | -10.8 |

| Shanghai | -21.7 | -11.9 | 73.9 | -65.2 | 104.9 |

| STOXX 50 | -8.4 | -0.1 | 28.5 | -44.6 | -2.2 |

| DAX | -14.7 | 16.1 | 23.8 | -40.4 | 22.0 |

| USD/EUR* | 3.2 | 6.7 | -2.9 | 4.7 | -10.7 |

| DJ UBS Com | -13.4 | 16.7 | 18.7 | -36.6 | 11.2 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

Sources:

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_eu.htm

The other yearly percentage changes in Table ES1 are also revealing of the wide fluctuations in valuations of risk financial assets. To be sure, economic conditions and perceptions of the future do influence valuations of risk financial assets. It is also valid to contend that unconventional monetary policy magnifies fluctuations in these valuations inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures with high leverage in risk financial assets such as equities, emerging equities, currencies, high-yield structured products and commodities futures and options. In fact, one of the alleged channels of transmission of unconventional monetary policy is through higher consumption induced by increases in wealth resulting from higher valuations of stock markets. Unconventional monetary policy could also result in magnification of values of risk financial assets beyond actual discounted future cash flows, creating financial instability. Separating all these effects in practice may be quite difficult because they are observed simultaneously while conclusive evidence would require contrasting what actually happened with the counterfactual of what would have happened in the absence of unconventional monetary policy and other effects. There is no certainty or evidence that unconventional policies attain their intended effects without risks of costly side effects. Yearly fluctuations of financial assets in Table ES1 are quite wide. In 2007, for example, the equity index Dow Global increased 30.9 percent while Dax gained 22.0 percent and the Shanghai Composite jumped 104.9 percent. The DJIA gained only 6.1 percent as recession began in IVQ2007. The flight to government obligations in 2008 (Cochrane and Zingales 2009, Cochrane 2011Jan) was equivalent to the astronomical declines of world equity markets and commodities. The flight from risk is also in evidence in the appreciation of the dollar by 4.7 percent in 2008 with unwinding carry trades and with renewed carry trades in the depreciation of the dollar by 2.9 percent in 2009. Recovery still continued in 2010 with shocks of the European debt crisis in the spring and in Nov. The flight from risk exposures dominated declines of valuations of risk financial assets in 2011.

Table ES2 is designed to provide a comparison of valuations of risk financial assets at the end of 2011 relative to valuations at the end of every year from 2006 to 2010. For example, the DJIA index is 5.5 percent higher at the end of 2011 relative to the valuation at the end of 2010 but is 2.3 percent below the valuation at the end of 2006 and 7.9 percent below the valuation at the end of 2007. It is higher by 39.2 percent relative to the depressed valuation at the end of 2008. Pre-recession valuations of 2006 and 2007 have not been recovered for all financial assets in Table ES2. With exception of gain by 5.5 percent by DJIA, all valuations of risk financial assets in Table ES2 are lower at the end of 2011 relative to their values at the end of 2010. Low valuations of risk financial assets are intimately related to risk aversion in international financial markets because of the European debt crisis, weakness and unemployment in advanced economies, fiscal imbalances and slowing growth in emerging economies.

Table ES2, Percentage Change of Year-end 2011 Values of Financial Assets Relative to Year-end Values 2006-2009

| 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | |

| DJIA | 5.5 | 17.2 | 39.2 | -7.9 | -2.3 |

| S&P 500 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 39.2 | -14.4 | -11.7 |

| NYSE Fin | -18.1 | -13.9 | 5.6 | -51.1 | -57.7 |

| Dow Global | -13.7 | -9.7 | 18.0 | -35.7 | -15.8 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -17.6 | -4.5 | 30.3 | -27.3 | -16.9 |

| Nikkei Av | -17.3 | -19.8 | -3.3 | -44.8 | -50.8 |

| Shanghai | -21.7 | -31.0 | 20.0 | -58.2 | -14.3 |

| STOXX 50 | -8.4 | -8.5 | 17.6 | -34.8 | -36.2 |

| DAX | -14.7 | -1.0 | 22.6 | -26.9 | -10.8 |

| USD/EUR* | 3.2 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 11.4 | 1.9 |

| DJ UBS Com | -13.4 | 1.1 | 20.0 | -23.9 | -15.4 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

Sources:

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_eu.htm

Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and large-scale purchases of assets using the central bank’s balance sheet is designed to increase aggregate demand by stimulating consumption and investment. In practice, there is no control of how cheap money will be used. An alternative allocation of cheap money is through the carry trade from zero interest rates and short dollar positions to exposures in risk financial assets such as equities, commodities and so on. After a decade of unconventional monetary policy it may be prudent to return to normalcy so as to avoid adverse side effects of financial turbulence and inflation waves. Normal monetary policy would also encourage financial intermediation required for financing sound long-term projects that can stimulate economic growth and full utilization of resources.

There are collateral concerns about European banks. David Enrich and Sara Schaefer Muñoz, writing on Dec 28, on “European bank worry: collateral,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203899504577126430202451796.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories), analyze the strain on bank funding from a squeeze in the availability of high-quality collateral as guarantee in funding. High-quality collateral includes government bonds and investment-grade non-government debt. There could be difficulties in funding for a bank without sufficient available high-quality collateral to offer in guarantee of loans. It is difficult to assess from bank balance sheets the availability of sufficient collateral to support bank funding requirements. There has been erosion in the quality of collateral as a result of the debt crisis and further erosion could occur. Perceptions of counterparty risk among financial institutions worsened the credit/dollar crisis of 2007 to 2009. The banking theory of Diamond and Rajan (2000, 2001a, 2001b) and the model of Diamond Dybvig (1983, 1986) provide the analysis of bank functions that explains the credit crisis of 2007 to 2008 (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a), 155-7, 48-52, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 52-66, 217-24). In fact, Rajan (2005, 339-41) anticipated the role of low interest rates in causing a hunt for yields in multiple financial markets from hedge funds to emerging markets and that low interest rates foster illiquidity. Rajan (2005, 341) argued:

“The point, therefore, is that common factors such as low interest rates—potentially caused by accommodative monetary policy—can engender excessive tolerance for risk on both sides of financial transactions.”

A critical function of banks consists of providing transformation services that convert illiquid risky loans and investment that the bank monitors into immediate liquidity such as unmonitored demand deposits. Credit in financial markets consists of the transformation of asset-backed securities (SRP) constructed with monitoring by financial institutions into unmonitored immediate liquidity by sale and repurchase agreements (SRP). In the financial crisis financial institutions distrusted the quality of their own balance sheets and those of their counterparties in SRPs. The financing counterparty distrusted that the financed counterparty would not repurchase the assets pledged in the SRP that could collapse in value below the financing provided. A critical problem was the unwillingness of banks to lend to each other in unsecured short-term loans. Emse Bartha, writing on Dec 28, on “Deposits at ECB hit high,” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204720204577125913779446088.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection), informs that banks deposited €453.034 billion, or $589.72 billion, at the ECB on Dec 28, which is a record high in two consecutive days. The deposit facility is typically used by banks when they do prefer not to extend unsecured loans to other banks. In addition, banks borrowed €6.225 billion from the overnight facility on Dec 28, when in normal times only a few hundred million euro are borrowed. The collateral issues and the possible increase in counterparty risk occurred a week after large-scale lender of last resort by the ECB in the value of €489 billion in the prior week. The ECB may need to extend its lender of last resort operations.

I Financial Risk Aversion. The critical fact of current world financial markets is the combination of “unconventional” monetary policy with intermittent shocks of financial risk aversion. This section is divided in four subsections. IA Unconventional Monetary Policy discusses the objectives of unconventional monetary policy. IB Financial Risk Aversion considers the causes of risk aversion. IC Financial Risk Valuations analyzes yearly data on financial risk valuations since 2006. ID Global Inflation Waves discusses shocks to world inflation originating in carry trades from zero interest rates to commodity futures. IE Summary summarizes some conclusions. IF Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy provides more technical discussion and references of unconventional monetary policy.

IA Unconventional Monetary Policy. There are two interrelated unconventional monetary policies. First, unconventional monetary policy consists of (1) reducing short-term policy interest rates toward the “zero bound” such as fixing the fed funds rate at 0 to ¼ percent by decision of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) since Dec 16, 2008 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm):

“The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to establish a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent.”

The FOMC reiterated the maintenance of the federal funds rate at 0 to ¼ percent for the foreseeable future as stated in the statement of the meeting on Dec 13, 2011 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20111213a.htm):

“The Committee also decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that economic conditions--including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run--are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.”

Second, unconventional monetary policy also includes a battery of measures to also reduce long-term interest rates of government securities and asset-backed securities such as mortgage-backed securities.

The objective of unconventional monetary policy is to implement the dual mandate of monetary policy of pursuing maximum employment and stable prices (http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/mission.htm):

“The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States. It was founded by Congress in 1913 to provide the nation with a safer, more flexible, and more stable monetary and financial system. Over the years, its role in banking and the economy has expanded.

Today, the Federal Reserve's duties fall into four general areas:

· conducting the nation's monetary policy by influencing the monetary and credit conditions in the economy in pursuit of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates

· supervising and regulating banking institutions to ensure the safety and soundness of the nation's banking and financial system and to protect the credit rights of consumers

· maintaining the stability of the financial system and containing systemic risk that may arise in financial markets

· providing financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions, including playing a major role in operating the nation's payments system”

When inflation is low, the central bank lowers interest rates to stimulate aggregate demand in the economy, which consists of consumption and investment. When inflation is subdued and unemployment high, monetary policy would lower interest rates to stimulate aggregate demand, reducing unemployment. When interest rates decline to zero, unconventional monetary policy would consist of policies such as large-scale purchases of long-term securities to lower their yields. A major portion of credit in the economy is financed with long-term asset-backed securities. Loans for purchasing houses, automobiles and other consumer products are bundled in securities that in turn are sold to investors. Corporations borrow funds for investment by issuing corporate bonds. Loans to small businesses are also financed by bundling them in long-term bonds. Securities markets bridge the needs of higher returns by savers obtaining funds from investors that are channeled to consumers and business for consumption and investment. Lowering the yields of these long-term bonds could lower costs of financing purchases of consumer durables and investment by business. The essential mechanism of transmission from lower interest rates to increases in aggregate demand is portfolio rebalancing. Withdrawal of bonds in a specific maturity segment or directly in a bond category such as currently mortgage-backed securities causes reductions in yield that are equivalent to increases in the prices of the bonds. There can be secondary increases in purchases of those bonds in private portfolios in pursuit of their increasing prices. Lower yields translate into lower costs of buying homes and consumer durables such as automobiles and also lower costs of investment for business. There are two additional intended routes of transmission. (1) Unconventional monetary policy or its expectation can increase stock market valuations (Bernanke 2010WP). Increases in equities traded in stock markets can increase the wealth of consumers inducing increases in consumption. (2) Unconventional monetary policy causes devaluation of the dollar relative to other currencies than can cause increases in net exports of the US that increase aggregate economic activity (2011AS).

Monetary policy can lower short-term interest rates quite effectively. Lowering long-term yields is somewhat more difficult. The critical issue is that monetary policy cannot ensure that increasing credit at low interest cost increases consumption and investment. There is a large variety of possible allocation of funds at low interest rates from consumption and investment to multiple risk financial assets. Monetary policy does not control how investors will allocate asset categories. A critical financial practice is to borrow at low short-term interest rates to invest in high-risk, leveraged financial assets. Investors may increase in their portfolios asset categories such as equities, emerging market equities, high-yield bonds, currencies, commodity futures and options and multiple other risk financial assets including structured products. If there is risk appetite, the carry trade from zero interest rates to risk financial assets will consist of short short-term interest rates (or borrowing) and short dollar assets with simultaneous long positions in high-risk, leveraged financial assets such as equities, commodities and high-yield bonds. Low interest rates may induce increases in valuations of risk financial assets that may fluctuate in accordance with perceptions of risk aversion by investors and the public. During periods of muted risk aversion, carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures in risk financial assets cause temporary waves of inflation that may foster instead of preventing financial stability. During periods of risk aversion such as fears of disruption of world financial markets and the global economy resulting from collapse of the European Monetary Union, carry trades are unwound with sharp deterioration of valuations of risk financial assets.

McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1974) argue that legal restrictions on financial institutions can be detrimental to economic development. “Financial repression” is the term used in the economic literature for these restrictions (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. II (2008b), 81-6). Interest rate ceilings on deposits and loans have been commonly used. Chart I-1 provides savings as percent of disposable income or the US savings rate. There was a long-term downward sloping trend from 12 percent in the early 1980s to less than 2 percent in 2005-2006. The savings rate then rose during the contraction and also in the expansion. In 2011 the savings rate declined as consumption is financed with savings in part because of the disincentive or frustration of receiving a few pennies for every $10,000 of deposits in a bank. The objective of monetary policy is to reduce borrowing rates to induce consumption but it has collateral disincentive of reducing savings. The zero interest rate of monetary policy is a tax on saving. This tax is highly regressive, meaning that it affects the most people with lower income or wealth and retirees. The long-term decline of savings rates in the US has created a dependence on foreign savings to finance the deficits in the federal budget and the balance of payments. Financial repression also disrupts portfolio management and asset/liability management such as, for example, choosing assets to match benefits and income in pension funds and actually all management of financial institutions. Functions of finance such as allocating savings to long-term sound projects (Pelaez and Pelaez, Financial Regulation after the Global Recession (2009a) 30-42, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 37-44, 45-60) can be frustrated, constraining the volume of financial intermediation required for economic growth.

Chart I-1, US, Personal Savings as a Percentage of Disposable Personal Income, Quarterly, 1980-2011

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm

IB Financial Risk Aversion. The most critical source of risk aversion in international financial markets is the fear of unfavorable unwinding of the debt crisis in Europe. Section II World Financial Turbulence analyzes in detail the euro zone debt crisis. Fears originating in the euro zone debt crisis dominate wide oscillations in equity and bond markets that are transmitted worldwide.

Another major concern is the weakness of the expansion phase beginning in IIIQ2009 after the global recession from IVQ2007 to IIQ2009. Advanced economies are growing slowly with high levels of unemployment as followed in this blog in Section IV World Economic Slowdown.

Risk aversion is manifested in withdrawal of investments from financial assets to assets in currencies and government obligations of countries that are immune from risk at least in the medium term. Investment funds seeking refuge from risk are channeled to the US dollar, Japanese yen and Swiss franc. Government obligations such as US Treasury securities and German government securities are favored relative to higher risks in equities and fixed-income. When risk appetite returns, funds flow away from safe havens toward higher risks, depreciating the dollar and increasing valuations of risk financial assets.

Zero interest rates induce carry trades that magnify valuations of risk financial assets in the absence of risk aversion. In the presence of risk aversion, cheap money flows to the safety of the dollar, Japanese yen and Swiss franc and the government obligations of the United States and Germany.

IC Financial Risk Valuations. Percentage changes of risk financial assets from the last day of the year relative to the last day of the earlier year are provided in Table I-1 from 2007 to 2011. The only gain for a major equity market in Table I-1 for 2011 is 5.5 percent for the DJIA. S&P 500 is better than other equity markets by remaining flat for 2011. With the exception of a drop of 8.4 percent of the European equity index STOXX 50, all declines of equity markets are in excess of 10 percent. China’s Shanghai Composite lost 21.7 percent. The equity index of Germany Dax fell 14.7 percent. The DJ UBS Commodities Index dropped 13.4 percent. Robin Wigglesworth, writing on Dec 30, 2011, on “$6.3tn wiped off markets in 2011,” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/483069d8-32f3-11e1-8e0d-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1i2BE7OPa

), provides an estimate of $6.3 trillion erased from equity markets globally in 2011. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO2011Aug, 90) estimates US nominal GDP in 2011 at $15,238 billion. The loss in equity markets worldwide in 2011 of $6.3 trillion is equivalent to about 41 percent of US GDP or economic activity in 2011. Table I-1 also provides the exchange rate of number of US dollars (USD) required in buying a unit of euro (EUR), USD/EUR. The dollar appreciated 3.2 percent on the last day of trading in 2011 relative to the last day of trading in 2010.

Table I-1, Percentage Change of Year-end Values of Financial Assets Relative to Earlier Year-end Values 2007-2010

| 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | |

| DJIA | 5.5 | 11.0 | 18.8 | -33.8 | 6.1 |

| S&P 500 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 23.5 | -38.5 | 3.1 |

| NYSE Fin | -18.1 | 5.0 | 22.7 | -53.6 | -13.5 |

| Dow Global | -13.7 | 4.6 | 30.8 | -45.5 | 30.9 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -17.6 | 15.9 | 36.4 | -44.2 | 14.2 |

| Nikkei Av | -17.3 | -3.0 | 20.6 | -42.9 | -10.8 |

| Shanghai | -21.7 | -11.9 | 73.9 | -65.2 | 104.9 |

| STOXX 50 | -8.4 | -0.1 | 28.5 | -44.6 | -2.2 |

| DAX | -14.7 | 16.1 | 23.8 | -40.4 | 22.0 |

| USD/EUR* | 3.2 | 6.7 | -2.9 | 4.7 | -10.7 |

| DJ UBS Com | -13.4 | 16.7 | 18.7 | -36.6 | 11.2 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

Sources:

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_eu.htm

The other yearly percentage changes in Table I-1 are also revealing of the wide fluctuations in valuations of risk financial assets. To be sure, economic conditions and perceptions of the future do influence valuations of risk financial assets. It is also valid to contend that unconventional monetary policy magnifies fluctuations in these valuations inducing carry trades from zero interest rates to exposures with high leverage in risk financial assets such as equities, emerging equities, currencies, high-yield structured products and commodities futures and options. In fact, one of the alleged channels of transmission of unconventional monetary policy is through higher consumption induced by increases in wealth resulting from higher valuations of stock markets. Unconventional monetary policy could also result in magnification of values of risk financial assets beyond actual discounted future cash flows, creating financial instability. Separating all these effects in practice may be quite difficult because they are observed simultaneously while conclusive evidence would require contrasting what actually happened with the counterfactual of what would have happened in the absence of unconventional monetary policy and other effects. There is no certainty or evidence that unconventional policies attain their intended effects without risks of costly side effects. Yearly fluctuations of financial assets in Table I-1 are quite wide. In 2007, for example, the equity index Dow Global increased 30.9 percent while Dax gained 22.0 percent and the Shanghai Composite jumped 104.9 percent. The DJIA gained only 6.1 percent as recession began in IVQ2007. The flight to government obligations in 2008 (Cochrane and Zingales 2009, Cochrane 2011Jan) was equivalent to the astronomical declines of world equity markets and commodities. The flight from risk is also in evidence in the appreciation of the dollar by 4.7 percent in 2008 with unwinding carry trades and with renewed carry trades in the depreciation of the dollar by 2.9 percent in 2009. Recovery still continued in 2010 with shocks of the European debt crisis in the spring and in Nov. The flight from risk exposures dominated declines of valuations of risk financial assets in 2011.

Table I-2 is designed to provide a comparison of valuations of risk financial assets at the end of 2011 relative to valuations at the end of every year from 2006 to 2010. For example, the DJIA index is 5.5 percent higher at the end of 2011 relative to the valuation at the end of 2010 but is 2.3 percent below the valuation at the end of 2006 and 7.9 percent below the valuation at the end of 2007. It is higher by 39.2 percent relative to the depressed valuation at the end of 2008. Pre-recession valuations of 2006 and 2007 have not been recovered for all financial assets in Table I-2. With exception of gain by 5.5 percent of DJIA, all valuations of risk financial assets in Table I-2 are lower at the end of 2011 relative to their values at the end of 2010. Low valuations of risk financial assets are intimately related to risk aversion in international financial markets because of the European debt crisis, weakness and unemployment in advanced economies, fiscal imbalances and slowing growth in emerging economies.

Table I-2, Percentage Change of Year-end 2011 Values of Financial Assets Relative to Year-end Values 2006-2009

| 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | |

| DJIA | 5.5 | 17.2 | 39.2 | -7.9 | -2.3 |

| S&P 500 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 39.2 | -14.4 | -11.7 |

| NYSE Fin | -18.1 | -13.9 | 5.6 | -51.1 | -57.7 |

| Dow Global | -13.7 | -9.7 | 18.0 | -35.7 | -15.8 |

| Dow Asia-Pacific | -17.6 | -4.5 | 30.3 | -27.3 | -16.9 |

| Nikkei Av | -17.3 | -19.8 | -3.3 | -44.8 | -50.8 |

| Shanghai | -21.7 | -31.0 | 20.0 | -58.2 | -14.3 |

| STOXX 50 | -8.4 | -8.5 | 17.6 | -34.8 | -36.2 |

| DAX | -14.7 | -1.0 | 22.6 | -26.9 | -10.8 |

| USD/EUR* | 3.2 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 11.4 | 1.9 |

| DJ UBS Com | -13.4 | 1.1 | 20.0 | -23.9 | -15.4 |

*Negative sign is dollar devaluation; positive sign is dollar appreciation

Sources:

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/Hist/dat00_eu.htm

ID Global Inflation Waves. The analysis of world inflation in this blog reveals three waves of inflation of producer and consumer prices. In the first wave from Jan to Apr of 2011, lack of risk aversion channeled cheap money into commodity futures, causing worldwide increase in inflation. In the second wave in May and Jun, risk aversion because of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe caused unwinding of the carry trade into commodity futures with resulting decline in commodity prices and inflation. In the third wave since Aug, alternations of risk aversion revived carry trades of commodity futures with resulting higher and lower inflation.

Table I-3 provides annual equivalent rates of inflation for producer prices indexes followed in this blog. The behavior of the US producer price index in 2011 shows neatly three waves. In Jan-Apr, without risk aversion, US producer prices rose at the annual equivalent rate of 17.3 percent. After risk aversion, producer prices increased in the US at the annual equivalent rate of 0.8 percent in May-Jul. Since Jul, under alternating episodes of risk aversion, producer prices have increased at the annual equivalent rate of 2.9 percent. Resolution of the European debt crisis would result in jumps of valuations of risk financial assets. Increases in commodity prices would cause the same high producer-price inflation experienced in Jan-Apr. There are seven producer-price indexes in Table I-3 showing very similar behavior in 2011. Zero interest rates without risk aversion cause increases in commodity prices that in turn increase input and output prices. Producer price inflation rose during the first part of the year for the US, China, Germany, France, Italy and the UK when risk aversion was contained. With the increase in risk aversion in May and Jun, inflation moderated because carry trades were unwound. Producer price inflation has returned since July, with alternating bouts of risk aversion.

Table I-3, Annual Equivalent Rates of Producer Price Indexes

| INDEX 2011 | AE ∆% |

| US Producer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | 2.9 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 0.8 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 17.3 |

| Japan Corporate Goods Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | -1.9 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 7.1 |

| China Producer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | -3.1 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Jun | 20.4 |

| Germany Producer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Oct | 4.6 |

| AE ∆% Jun-May | 1.2 |

| Jan-Apr | 7.1 |

| France Producer Price Index for the French Market | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Oct | 3.4 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | -3.5 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 11.4 |

| Italy Producer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | 1.4 |

| AE ∆% Jun-May | -1.2 |

| AE ∆% Jan-April | 10.7 |

| UK Output Prices | |

| AE ∆% May-Nov | 2.1 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 12.0 |

| UK Input Prices | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | -0.1 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | -8.7 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 35.6 |

Sources: http://www.bls.gov/ppi/data.htm

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1111.pdf

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111209_402771437.htm

http://www.insee.fr/en/themes/info-rapide.asp?id=25&date=20111130

http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/47110

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ppi2/producer-price-index/november-2011/index.html

Annual equivalent consumer price inflation in the US in Jan-Apr reached 7.5 percent as carry trades raised commodity futures, as shown in Table I-4. Return of risk aversion in May to Jul resulted in annual equivalent inflation of only 2.0 percent in May-Jul. Inflation then rose again in Jul-Oct to annual equivalent 3.3 percent with alternation of bouts of risk aversion and 2.7 in Jul-Nov. The three waves are neatly repeated in consumer price inflation for China, the euro zone, Germany, France, Italy and the UK. In the absence of risk aversion, zero interest rates with guidance now forever, induce carry trades that raise commodity prices, increasing prices.

Table I-4, Annual Equivalent Rates of Consumer Price Indexes

| Index 2011 | AE ∆% |

| US Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | 2.7 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | 2.0 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 7.5 |

| China Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | 2.9 |

| AE ∆% Apr-Jun | 2.0 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Mar | 8.3 |

| Euro Zone Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices | |

| AE ∆% Aug-Nov | 4.3 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | -2.4 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 5.2 |

| Germany Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Dec | 2.4 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | 0.6 |

| AE ∆% Feb-Apr | 4.9 |

| France Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Aug-Nov | 3.0 |

| AE ∆% May-Jul | -1.2 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 4.3 |

| Italy Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Jul-Nov | 2.7 |

| AE ∆% May-Jun | 1.2 |

| AE ∆% Jan-Apr | 4.9 |

| UK Consumer Price Index | |

| AE ∆% Aug-Nov | 4.6 |

| May-Jul | 0.4 |

| Jan-Apr | 6.5 |

Sources: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

http://www.stats.gov.cn/enGliSH/newsandcomingevents/t20111209_402771439.htm

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/2-15122011-AP/EN/2-15122011-AP-EN.PDF

http://www.insee.fr/en/themes/info-rapide.asp?id=29&date=20111213

http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/48180

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/cpi/consumer-price-indices/november-2011/index.html

IE Summary. Unconventional monetary policy of zero interest rates and large-scale purchases of assets using the central bank’s balance sheet is designed to increase aggregate demand by stimulating consumption and investment. In practice, there is no control of how cheap money will be used. An alternative allocation of cheap money is through the carry trade from zero interest rates and short dollar positions to exposures in risk financial assets such as equities, commodities and so on. After a decade of unconventional monetary policy it may be prudent to return to normalcy so as to avoid adverse side effects of financial turbulence and inflation waves. Normal monetary policy would also encourage financial intermediation required for financing sound long-term projects that can stimulate economic growth and full utilization of resources.

IF Appendix: Transmission of Unconventional Monetary Policy. Janet L. Yellen, Vice Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, provides analysis of the policy of purchasing large amounts of long-term securities for the Fed’s balance sheet. The new analysis provides three channels of transmission of quantitative easing to the ultimate objectives of increasing growth and employment and increasing inflation to “levels of 2 percent or a bit less that most Committee participants judge to be consistent, over the long run, with the FOMC’s dual mandate” (Yellen 2011AS, 4, 7):

“There are several distinct channels through which these purchases tend to influence aggregate demand, including a reduced cost of credit to consumers and businesses, a rise in asset prices that boost household wealth and spending, and a moderate change in the foreign exchange value of the dollar that provides support to net exports.”

The new analysis by Yellen (2011AS) is considered below in four separate subsections: IFi Theory; IFii Policy; IFiii Evidence; and IFiv Unwinding Strategy.

IFi Theory. The transmission mechanism of quantitative easing can be analyzed in three different forms. (1) Portfolio choice theory. General equilibrium value theory was proposed by Hicks (1935) in analyzing the balance sheets of individuals and institutions with assets in the capital segment consisting of money, debts, stocks and productive equipment. Net worth or wealth would be comparable to income in value theory. Expected yield and risk would be the constraint comparable to income in value theory. Markowitz (1952) considers a portfolio of individual securities with mean μp and variance σp. The Markowitz (1952, 82) rule states that “investors would (or should” want to choose a portfolio of combinations of (μp, σp) that are efficient, which are those with minimum variance or risk for given expected return μp or more and maximum expected μp for given variance or risk or less. The more complete model of Tobin (1958) consists of portfolio choice of monetary assets by maximizing a utility function subject to a budget constraint. Tobin (1961, 28) proposes general equilibrium analysis of the capital account to derive choices of capital assets in balance sheets of economic units with the determination of yields in markets for capital assets with the constraint of net worth. A general equilibrium model of choice of portfolios was developed simultaneously by various authors (Hicks 1962; Treynor 1962; Sharpe 1964; Lintner 1965; Mossin 1966). If shocks such as by quantitative easing displace investors from the efficient frontier, there would be reallocations of portfolios among assets until another efficient point is reached. Investors would bid up the prices or lower the returns (interest plus capital gains) of long-term assets targeted by quantitative easing, causing the desired effect of lowering long-term costs of investment and consumption.

(2) General Equilibrium Theory. Bernanke and Reinhart (2004, 88) argue that “the possibility monetary policy works through portfolio substitution effects, even in normal times, has a long intellectual history, having been espoused by both Keynesians (James Tobin 1969) and monetarists (Karl Brunner and Allan Meltzer 1973).” Andres et al. (2004) explain the Tobin (1969) contribution by optimizing agents in a general-equilibrium model. Both Tobin (1969) and Brunner and Meltzer (1973) consider capital assets to be gross instead of perfect substitutes with positive partial derivatives of own rates of return and negative partial derivatives of cross rates in the vector of asset returns (interest plus principal gain or loss) as argument in portfolio balancing equations (see Pelaez and Suzigan 1978, 113-23). Tobin (1969, 26) explains portfolio substitution after monetary policy:

“When the supply of any asset is increased, the structure of rates of return, on this and other assets, must change in a way that induces the public to hold the new supply. When the asset’s own rate can rise, a large part of the necessary adjustment can occur in this way. But if the rate is fixed, the whole adjustment must take place through reductions in other rates or increases in prices of other assets. This is the secret of the special role of money; it is a secret that would be shared by any other asset with a fixed interest rate.”

Andrés et al. (2004, 682) find that in their multiple-channels model “base money expansion now matters for the deviations of long rates from the expected path of short rates. Monetary policy operates by both the expectations channel (the path of current and expected future short rates) and this additional channel. As in Tobin’s framework, interest rates spreads (specifically, the deviations from the pure expectations theory of the term structure) are an endogenous function of the relative quantities of assets supplied.”

The interrelation among yields of default-free securities is measured by the term structure of interest rates. This schedule of interest rates along time incorporates expectations of investors. (Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1985). The expectations hypothesis postulates that the expectations of investors about the level of future spot rates influence the level of current long-term rates. The normal channel of transmission of monetary policy in a recession is to lower the target of the fed funds rate that will lower future spot rates through the term structure and also the yields of long-term securities. The expectations hypothesis is consistent with term premiums (Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1981, 774-7) such as liquidity to compensate for risk or uncertainty about future events that can cause changes in prices or yields of long-term securities (Hicks 1939; see Cox, Ingersoll and Ross 1981, 784; Chung et al. 2011, 22).

(3) Preferred Habitat. Another approach is by the preferred-habitat models proposed by Culbertson (1957, 1963) and Modigliani and Sutch (1966). This approach is formalized by Vayanos and Vila (2009). The model considers investors or “clientele” who do not abandon their segment of operations unless there are extremely high potential returns and arbitrageurs who take positions to profit from discrepancies. Pension funds matching benefit liabilities would operate in segments above 15 years; life insurance companies operate around 15 years or more; and asset managers and bank treasury managers are active in maturities of less than 10 years (Ibid, 1). Hedge funds, proprietary trading desks and bank maturity transformation activities are examples of potential arbitrageurs. The role of arbitrageurs is to incorporate “information about current and future short rates into bond prices” (Ibid, 12). Suppose monetary policy raises the short-term rate above a certain level. Clientele would not trade on this information, but arbitrageurs would engage in carry trade, shorting bonds and investing at the short-term rate, in a “roll-up” trade, resulting in decline of bond prices or equivalently increases in yields. This is a situation of an upward-sloping yield curve. If the short-term rate were lowered, arbitrageurs would engage in carry trade borrowing at the short-term rate and going long bonds, resulting in an increase in bond prices or equivalently decline in yields, or “roll-down” trade. The carry trade is the mechanism by which bond yields adjust to changes in current and expected short-term interest rates. The risk premiums of bonds are positively associated with the slope of the term structure (Ibid, 13). Fama and Bliss (1987, 689) find with data for 1964-85 that “1-year expected returns for US Treasury maturities to 5 years, measured net of the interest rate on a 1-year bond, vary through time. Expected term premiums are mostly positive during good times but mostly negative during recessions.” Vayanos and Vila (2009) develop a model with two-factors, the short-term rate and demand or quantity. The term structure moves because of shocks of short-term rates and demand. An important finding is that demand or quantity shocks are largest for intermediate and long maturities while short-rate shocks are largest for short-term maturities.

IFii Policy. A simplified analysis could consider the portfolio balance equations Aij = f(r, x) where Aij is the demand for i = 1,2,∙∙∙n assets from j = 1,2, ∙∙∙m sectors, r the 1xn vector of rates of return, ri, of n assets and x a vector of other relevant variables. Tobin (1969) and Brunner and Meltzer (1973) assume imperfect substitution among capital assets such that the own first derivatives of Aij are positive, demand for an asset increases if its rate of return (interest plus capital gains) is higher, and cross first derivatives are negative, demand for an asset decreases if the rate of return of alternative assets increases. Theoretical purity would require the estimation of the complete model with all rates of return. In practice, it may be impossible to observe all rates of return such as in the critique of Roll (1976). Policy proposals by the Fed have been focused on the likely impact of withdrawals of stocks of securities in specific segments, that is, of effects of one or several specific rates of return among the n possible rates. There have been at least seven approaches on the role of monetary policy in purchasing long-term securities that have increased the classes of rates of return targeted by the Fed:

i. Suspension of Auctions of 30-year Treasury Bonds. Auctions of 30-year Treasury bonds were suspended between 2001 and 2005. This was Treasury policy not Fed policy. The effects were similar to those of quantitative easing: withdrawal of supply from the segment of 30-year bonds would result in higher prices or lower yields for close-substitute mortgage-backed securities with resulting lower mortgage rates. The objective was to encourage refinancing of house loans that would increase family income and consumption by freeing income from reducing monthly mortgage payments.

ii. Purchase of Long-term Securities by the Fed. Between Nov 2008 and Mar 2009 the Fed announced the intention of purchasing $1750 billion of long-term securities: $600 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities and agency debt announced on Nov 25 and $850 billion of agency mortgaged-backed securities and agency debt plus $300 billion of Treasury securities announced on Mar 18, 2009 (Yellen 2011AS, 5-6). The objective of buying mortgage-backed securities was to lower mortgage rates that would “support the housing sector” (Bernanke 2009SL). The FOMC statement on Dec 16, 2008 informs that: “over the next few quarters the Federal Reserve will purchase large quantities of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities to provide support to the mortgage and housing markets, and its stands ready to expand its purchases of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities as conditions warrant” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081216b.htm). The Mar 18 statement of the FOMC explained that: “to provide greater support to mortgage lending and housing markets, the Committee decided today to increase the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet further by purchasing up to an additional $750 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities, bringing its total purchases of these securities up to $1.25 trillion this year, and to increase its purchase of agency debt this year by up to $100 billion to a total of up to $200 billion. Moreover, to help improve conditions in private credit markets, the Committee decided to purchase up to $300 billion of longer-term Treasury securities over the next six months” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20090318a.htm). Policy changed to increase prices or reduce yields of mortgage-backed securities and Treasury securities with the objective of supporting housing markets and private credit markets by lowering costs of housing and long-term private credit.

iii. Portfolio Reinvestment. On Aug 10, 2010, the FOMC statement explains the reinvestment policy: “to help support the economic recovery in a context of price stability, the Committee will keep constant the Federal Reserve’s holdings of securities at their current level by reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in long-term Treasury securities. The Committee will continue to roll over the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities as they mature” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20100810a.htm). The objective of policy appears to be supporting conditions in housing and mortgage markets with slow transfer of the portfolio to Treasury securities that would support private-sector markets.

iv. Increasing Portfolio. As widely anticipated, the FOMC decided on Dec 3, 2010: “to promote a stronger pace of economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with its mandate, the Committee decided today to expand its holdings of securities. The Committee will maintain its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its securities holdings. In addition, the Committee intends to purchase a further $600 billion of longer-term Treasury securities by the end of the second quarter of 2011, a pace of about $75 billion per month” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20101103a.htm). The emphasis appears to shift from housing markets and private-sector credit markets to the general economy, employment and preventing deflation.

v. Increasing Stock Market Valuations. Chairman Bernanke (2010WP) explained on Nov 4 the objectives of purchasing an additional $600 billion of long-term Treasury securities and reinvesting maturing principal and interest in the Fed portfolio. Long-term interest rates fell and stock prices rose when investors anticipated the new round of quantitative easing. Growth would be promoted by easier lending such as for refinancing of home mortgages and more investment by lower corporate bond yields. Consumers would experience higher confidence as their wealth in stocks rose, increasing outlays. Income and profits would rise and, in a “virtuous circle,” support higher economic growth. Bernanke (2000) analyzes the role of stock markets in central bank policy (see Pelaez and Pelaez, Regulation of Banks and Finance (2009b), 99-100). Fed policy in 1929 increased interest rates to avert a gold outflow and failed to prevent the deepening of the banking crisis without which the Great Depression may not have occurred. In the crisis of Oct 19, 1987, Fed policy supported stock and futures markets by persuading banks to extend credit to brokerages. Collapse of stock markets would slow consumer spending.

vi. Devaluing the Dollar. Yellen (2011AS, 6) broadens the effects of quantitative easing by adding dollar devaluation: “there are several distinct channels through which these purchases tend to influence aggregate demand, including a reduced cost of credit to consumers and businesses, a rise in asset prices that boosts household wealth and spending, and a moderate change in the foreign exchange value of the dollar that provides support to net exports.”

vii. Let’s Twist Again Monetary Policy. The term “operation twist” grew out of the dance “twist” popularized by successful musical performer Chubby Chekker (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWaJ0s0-E1o). Meulendyke (1998, 39) describes the coordination of policy by Treasury and the FOMC in the beginning of the Kennedy administration in 1961 (see Modigliani and Sutch 1966, 1967; http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/imf-view-of-world-economy-and-finance.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/collapse-of-household-income-and-wealth.html):

“In 1961, several developments led the FOMC to abandon its “bills only” restrictions. The new Kennedy administration was concerned about gold outflows and balance of payments deficits and, at the same time, it wanted to encourage a rapid recovery from the recent recession. Higher rates seemed desirable to limit the gold outflows and help the balance of payments, while lower rates were wanted to speed up economic growth.

To deal with these problems simultaneously, the Treasury and the FOMC attempted to encourage lower long-term rates without pushing down short-term rates. The policy was referred to in internal Federal Reserve documents as “operation nudge” and elsewhere as “operation twist.” For a few months, the Treasury engaged in maturity exchanges with trust accounts and concentrated its cash offerings in shorter maturities.

The Federal Reserve participated with some reluctance and skepticism, but it did not see any great danger in experimenting with the new procedure.

It attempted to flatten the yield curve by purchasing Treasury notes and bonds while selling short-term Treasury securities. The domestic portfolio grew by $1.7 billion over the course of 1961. Note and bond holdings increased by a substantial $8.8 billion, while certificate of indebtedness holdings fell by almost $7.4 billion (Table 2). The extent to which these actions changed the yield curve or modified investment decisions is a source of dispute, although the predominant view is that the impact on yields was minimal. The Federal Reserve continued to buy coupon issues thereafter, but its efforts were not very aggressive. Reference to the efforts disappeared once short-term rates rose in 1963. The Treasury did not press for continued Fed purchases of long-term debt. Indeed, in the second half of the decade, the Treasury faced an unwanted shortening of its portfolio. Bonds could not carry a coupon with a rate above 4 1/4 percent, and market rates persistently exceeded that level. Notes—which were not subject to interest rate restrictions—had a maximum maturity of five years; it was extended to seven years in 1967.”

As widely anticipated by markets, perhaps intentionally, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided at its meeting on Sep 21 that it was again “twisting time” (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20110921a.htm):

“Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in August indicates that economic growth remains slow. Recent indicators point to continuing weakness in overall labor market conditions, and the unemployment rate remains elevated. Household spending has been increasing at only a modest pace in recent months despite some recovery in sales of motor vehicles as supply-chain disruptions eased. Investment in nonresidential structures is still weak, and the housing sector remains depressed. However, business investment in equipment and software continues to expand. Inflation appears to have moderated since earlier in the year as prices of energy and some commodities have declined from their peaks. Longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee continues to expect some pickup in the pace of recovery over coming quarters but anticipates that the unemployment rate will decline only gradually toward levels that the Committee judges to be consistent with its dual mandate. Moreover, there are significant downside risks to the economic outlook, including strains in global financial markets. The Committee also anticipates that inflation will settle, over coming quarters, at levels at or below those consistent with the Committee's dual mandate as the effects of past energy and other commodity price increases dissipate further. However, the Committee will continue to pay close attention to the evolution of inflation and inflation expectations.

To support a stronger economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with the dual mandate, the Committee decided today to extend the average maturity of its holdings of securities. The Committee intends to purchase, by the end of June 2012, $400 billion of Treasury securities with remaining maturities of 6 years to 30 years and to sell an equal amount of Treasury securities with remaining maturities of 3 years or less. This program should put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates and help make broader financial conditions more accommodative. The Committee will regularly review the size and composition of its securities holdings and is prepared to adjust those holdings as appropriate.

To help support conditions in mortgage markets, the Committee will now reinvest principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities. In addition, the Committee will maintain its existing policy of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction.

The Committee also decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that economic conditions--including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run--are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.

The Committee discussed the range of policy tools available to promote a stronger economic recovery in a context of price stability. It will continue to assess the economic outlook in light of incoming information and is prepared to employ its tools as appropriate.”

IFiii Evidence. There are multiple empirical studies on the effectiveness of quantitative easing that have been covered in past posts such as (Andrés et al. 2004, D’Amico and King 2010, Doh 2010, Gagnon et al. 2010, Hamilton and Wu 2010). On the basis of simulations of quantitative easing with the FRB/US econometric model, Chung et al (2011, 28-9) find that:

”Lower long-term interest rates, coupled with higher stock market valuations and a lower foreign exchange value of the dollar, provide a considerable stimulus to real activity over time. Phase 1 of the program by itself is estimated to boost the level of real GDP almost 2 percent above baseline by early 2012, while the full program raises the level of real GDP almost 3 percent by the second half of 2012. This boost to real output in turn helps to keep labor market conditions noticeably better than they would have been without large scale asset purchases. In particular, the model simulations suggest that private payroll employment is currently 1.8 million higher, and the unemployment rate ¾ percentage point lower, that would otherwise be the case. These benefits are predicted to grow further over time; by 2012, the incremental contribution of the full program is estimated to be 3 million jobs, with an additional 700,000 jobs provided by the most recent phase of the program alone.”

An additional conclusion of these simulations is that quantitative easing may have prevented actual deflation. Empirical research is continuing.

IFiv Unwinding Strategy. Fed Vice-Chair Yellen (2011AS) considers four concerns on quantitative easing discussed below in turn. First, Excessive Inflation. Yellen (2011AS, 9-12) considers concerns that quantitative easing could result in excessive inflation because fast increases in aggregate demand from quantitative easing could raise the rate of inflation, posing another problem of adjustment with tighter monetary policy or higher interest rates. The Fed estimates significant slack of resources in the economy as measured by the difference of four percentage points between the high current rate of unemployment above 9 percent and the NAIRU (non-accelerating rate of unemployment) of 5.75 percent (Ibid, 2). Thus, faster economic growth resulting from quantitative easing would not likely result in upward trend of costs as resources are bid up competitively. The Fed monitors frequently slack indicators and is committed to maintaining inflation at a “level of 2 percent or a bit less than that” (Ibid, 13), say, in the narrow open interval (1.9, 2.1).

Second, Inflation and Bank Reserves. On Jan 12, the line “Reserve Bank credit” in the Fed balance sheet stood at $2450.6 billion, or $2.5 trillion, with the portfolio of long-term securities of $2175.7 billion, or $2.2 trillion, composed of $987.6 billion of notes and bonds, $49.7 billion of inflation-adjusted notes and bonds, $146.3 billion of Federal agency debt securities, and $992.1 billion of mortgage-backed securities; reserves balances with Federal Reserve Banks stood at $1095.5 billion, or $1.1 trillion (http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm#h41tab1). The concern addressed by Yellen (2011AS, 12-4) is that this high level of reserves could eventually result in demand growth that could accelerate inflation. Reserves would be excessively high relative to the levels before the recession. Reserves of depository institutions at the Federal Reserve Banks rose from $45.6 billion in Aug 2008 to $1084.8 billion in Aug 2010, not seasonally adjusted, multiplying by 23.8 times, or to $1038.2 billion in Nov 2010, multiplying by 22.8 times. The monetary base consists of the monetary liabilities of the government, composed largely of currency held by the public plus reserves of depository institutions at the Federal Reserve Banks. The monetary base not seasonally adjusted, or issue of money by the government, rose from $841.1 billion in Aug 2008 to $1991.1 billion or by 136.7 percent and to $1968.1 billion in Nov 2010 or by 133.9 percent (http://federalreserve.gov/releases/h3/hist/h3hist1.pdf). Policy can be viewed as creating government monetary liabilities that ended mostly in reserves of banks deposited at the Fed to purchase $2.1 trillion of long-term securities or assets, which in nontechnical language would be “printing money” (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2010/12/is-fed-printing-money-what-are.html). The marketable debt of the US government in Treasury securities held by the public stood at $8.7 trillion on Nov 30, 2010 (http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2010/opds112010.pdf). The current holdings of long-term securities by the Fed of $2.1 trillion, in the process of converting fully into Treasury securities, are equivalent to 24 percent of US government debt held by the public, and would represent 29.9 percent with the new round of quantitative easing if all the portfolio of the Fed, as intended, were in Treasury securities. Debt in Treasury securities held by the public on Dec 31, 2009, stood at $7.2 trillion (http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2009/opds122009.pdf), growing to Nov 30, 2010, by $1.5 trillion or by 20.8 percent. In spite of this growth of bank reserves, “the 12-month change in core PCE [personal consumption expenditures] prices dropped from about 2 ½ percent in mid-2008 to around 1 ½ percent in 2009 and declined further to less than 1 percent by late 2010” (Yellen 2011AS, 3). The PCE price index, excluding food and energy, is around 0.8 percent in the past 12 months, which could be, in the Fed’s view, too close for comfort to negative inflation or deflation. Yellen (2011AS, 12) agrees “that an accommodative monetary policy left in place too long can cause inflation to rise to undesirable levels” that would be true whether policy was constrained or not by “the zero bound on interest rates.” The FOMC is monitoring and reviewing the “asset purchase program regularly in light of incoming information” and will “adjust the program as needed to meet its objectives” (Ibid, 12). That is, the FOMC would withdraw the stimulus once the economy is closer to full capacity to maintain inflation around 2 percent. In testimony at the Senate Committee on the Budget, Chairman Bernanke stated that “the Federal Reserve has all the tools its needs to ensure that it will be able to smoothly and effectively exit from this program at the appropriate time” (http://federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/bernanke20110107a.htm). The large quantity of reserves would not be an obstacle in attaining the 2 percent inflation level. Yellen (2011A, 13-4) enumerates Fed tools that would be deployed to withdraw reserves as desired: (1) increasing the interest rate paid on reserves deposited at the Fed currently at 0.25 percent per year; (2) withdrawing reserves with reverse sale and repurchase agreement in addition to those with primary dealers by using mortgage-backed securities; (3) offering a Term Deposit Facility similar to term certificates of deposit for member institutions; and (4) sale or redemption of all or parts of the portfolio of long-term securities. The Fed would be able to increase interest rates and withdraw reserves as required to attain its mandates of maximum employment and price stability.

Third, Financial Imbalances. Fed policy intends to lower costs to business and households with the objective of stimulating investment and consumption generating higher growth and employment. Yellen (2011A, 14-7) considers a possible consequence of excessively reducing interest rates: “a reasonable fear is that this process could go too far, encouraging potential borrowers to employ excessive leverage to take advantage of low financing costs and leading investors to accept less compensation for bearing risks as they seek to enhance their rates of return in an environment of very low yields. This concern deserves to be taken seriously, and the Federal Reserve is carefully monitoring financial indicators for signs of potential threats to financial stability.” Regulation and supervision would be the “first line of defense” against imbalances threatening financial stability but the Fed would also use monetary policy to check imbalances (Yellen 2011AS, 17).

Fourth, Adverse Effects on Foreign Economies. The issue is whether the now recognized dollar devaluation would promote higher growth and employment in the US at the expense of lower growth and employment in other countries.

II International Financial Turbulence. Financial markets are being shocked by multiple factors including (1) world economic slowdown; (2) growth in China, Japan and world trade; (3) slow growth propelled by savings reduction in the US with high unemployment/underemployment; and (3) the outcome of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe. This section analyzes the events of the week culminating in the meeting of European leaders. Subsection IIA Financial Risks provides analysis of the evolution of valuations of risk assets during the week. Subsection IIB Fiscal Compact analysis the restructuring of the fiscal affairs of the European Union in the agreement of European leaders on Dec 9. Subsection IIC European Central Bank Large Scale Lender of Last Resort considers the policies of the European Central Bank. Subsection IID Euro Zone Survival Risk analyzes the threats to survival of the European Monetary Union. Subsection IIE Appendix on Sovereign Bond Valuation provides more technical analysis.