Financial Risk Aversion, Hiring Collapse and Global Inflation, Trade and Growth

Carlos M. Pelaez

© Carlos M. Pelaez, 2010, 2011

Executive Summary

I Financial Risk Aversion

II Hiring Collapse

III Global Inflation

IV Trade and Growth

V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

VI Economic Indicators

VII Interest Rates

VIII Conclusion

References

Executive Summary

Hiring in the US nonfarm sector has declined from 64.9 million in 2006 to 47.2 million in 2010 or by 17.7 million while hiring in the private sector has declined from 60.4 million in 2006 to 43.3 million in 2010 or by 17.1 million. An important characteristic of the labor market in the US is that the latest available monthly statistics show hiring in the nonfarm sector has declined from 6.010 million in May 2006 to 4.531 million in May 2011, or by 1.479 million, and hiring in the private sector has fallen from 5.631 million in May 2006 to 4.250 million in May 2011, or by 1.381 million. Hiring in the nonfarm sector of 4.531 million in May 2011 is almost unchanged relative to 4.746 million in May 2010 and hiring in the private sector in May 2011 of 4.250 million is lower by 1.256 million than 5.506 million in May 2001. The US labor market is fractured, creating fewer opportunities to exit job stress of unemployment and underemployment of 25 to 30 million people and declining inflation-adjusted wages in the midst of fast increases in prices of everything. There are major financial vulnerabilities in the international financial system that could stress again global financial markets.

An article in Real Time Economics of the Wall Street Journal on Jul 16 on “Number of the week: 5% unemployment could be a decade away” (http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2011/07/16/number-of-the-week-5-unemployment-could-be-over-a-decade-away/) provides an approximation of the number of months that would be required for the economy to return to the 5 percent unemployment rate of 2007. The current unemployment rate for Jun is 9.2 percent, with 14.1 million unemployed, on the basis of the household survey. Job creation in the first half of 2011 was 757,000 jobs, on the basis of the establishment survey. Assuming that job creation is approximately the same in the household survey as in the establishment survey, there would be a gain of 1.6 million new jobs in the year forward from Jun 2011 to Jun 2012. Real Time Economics adds to the calculation the growth of the labor force projected by the Census as 1.4 million people aged 16 and over. Employment would grow by 1.6 million while the labor force would grow by 1.4 million, reducing unemployment by only 200,000 that would still leave the rate of unemployment at 8.9 percent. Under those assumptions about employment growth and labor force growth, the rate of unemployment of 5 percent would only be attained in Dec 2024. Another recession would create a setback in the calculations. An important issue is that there are an additional 4 million unemployed who are not counted because they abandoned the hope of finding another job, such that the total unemployment in Jun is more likely to be closer to 18.4 million. To that would have to be added 8.6 million barely making a living in part-time jobs because they cannot find anything better and 2.7 million marginally attached to the labor force. The total number of people in job stress in the US is 29.693 million in Jun 2011 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html). The US is suffering a suffocating unemployment and underemployment stress that would require much faster growth than that experienced in the weakest recovery from a recession since World War II. Faster growth is the only form of reigniting the fractured US labor market

I Financial Risk Aversion. The past two months have been characterized by unusual financial turbulence. Table 1, updated with every comment in this blog, provides beginning values on Jul 11 and daily values throughout the week ending on Jul 15. All data are for New York time at 5 PM. The first three rows provide three key exchange rates versus the dollar and the percentage cumulative appreciation (positive change or no sign) or depreciation (negative change or negative sign). Positive changes constitute appreciation of the relevant exchange rate and negative changes depreciation. In a sign of financial risk aversion, the dollar appreciated 0.7 percent relative to the euro by Jul 15, with outflow of funds from risk financial assets. The dollar appreciated in the prior week by 1.8 percent relative to the euro because of renewed fears of default in Greece that could have adverse repercussions in sovereign debts of other countries in Europe’s “periphery” as well as in “core countries” through exposures of banks. A combination of renewed fears of default, downgrade of Ireland, rise in bond spreads and declining bank stocks in Italy, the weak employment report of the US and alerts on downgrading of US debt in case of failure of increase of the federal debt limit were important factors in the appreciation of the dollar by Jul 15. The Japanese yen appreciated during the week reaching JPY 79.13/USD by Fr Jul 15, which is quite strong as the currency is used as safe haven from world risks while fears of another Japanese and G7 intervention subsided. The Swiss franc appreciated 2.6 percent during the week, reaching CHF 0.816/USD on Fri Jul 15, which reflects risk aversion by funds flowing away from risk positions to temporarily benefitting from safe haven in a strong deposit and investment market.

Table 1, Daily Valuation of Risk Financial Assets

| Jul 11 | Jul 12 | Jul 13 | Jul 14 | Jul 15 | |

| USD/ | 1.4031 1.6% | 1.3978 1.9% | 1.4151 0.8% | 1.4140 0.8% | 1.4157 0.7% |

| JPY/ | 80.2535 0.4% | 79.3495 1.6% | 78.9945 2.0% | 79.1535 1.8% | 79.13 1.8% |

| CHF/ | 0.8355 0.3% | 0.8315 0.8% | 0.8187 2.3% | 0.8163 2.6% | 0.816 2.6% |

| 10 Year Yield | 2.92 | 2.88 | 2.88 | 2.95 | 2.905 |

| 2 Year Yield | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.356 |

| 10 Year | 2.67 | 2.71 | 2.75 | 2.74 | 2.70 |

| DJIA | -1.2% -1.2% | -1.7% -0.5% | -1.3% 0.4% | -1.7% -0.4% | -1.4% 0.3% |

| DJ Global | -2.1% -2.1% | -2.9% -0.9% | -1.9% 1.1% | -2.5% -0.6% | -2.5% 0.01% |

| DAX | -2.3% -2.3% | -3.1% -0.8% | -1.8% 1.3% | -2.5% -0.7% | -2.5% 0.1% |

| DJ Asia Pacific | -1.0% -1.0% | -2.6% -1.6% | -1.4% 1.2% | -1.7% -0.3% | -1.6% 0.1% |

| WTI $/b | 95.14 -1.3% -1.3% | 96.790 0.4% 1.7% | 97.86 1.5% 1.1% | 95.940 -0.5% -1.9% | 97.430 1.1% 1.6% |

| Brent $/b | 117.10 -1.1% -1.1% | 117.19 -1.0% 0.1% | 118.76 0.3% 1.3% | 116.43 –1.6% -1.9% | 117.66 -0.6% 1.1% |

| Gold $/ounce | 1554.00 0.7% 0.7% | 1569.70. 1.7% 1.0% | 1581.90 2.5% 0.8% | 1586.00 2.7% 0.3% | 1594.20 3.3% 0.5% |

Note: For the exchange rates the percentage is the cumulative change since Fri the prior week; for the exchange rates appreciation is a positive percentage and depreciation a negative percentage; USD: US dollar; JPY: Japanese Yen; CHF: Swiss Franc; AUD: Australian dollar; B: barrel; for the four stock indexes and prices of oil and gold the upper line is the percentage change since the past week and the lower line the percentage change from the prior day;

Source: http://noir.bloomberg.com/intro_markets.html

http://professional.wsj.com/mdc/page/marketsdata.html?mod=WSJ_hps_marketdata

The three sovereign bond yields in Table 1 capture renewed risk aversion in the flight away from risk financial assets toward the safety of US Treasury securities and German securities. The 2-year US Treasury note is highly attractive because of minimal duration or sensitivity to price change and its yield continued fluctuating in a tight low range between 0.356 and 0.37 percent. There is generalized expectation in financial markets, shown by normal bid/coverage ratios in the auctions of three, ten and thirty year US Treasury bonds, that there will not be default of US debt because of political failure to raise the debt limit. Much the same is true of the 10-year Treasury note and the 10-year bond of the government of Germany, falling to 2.905 percent for the 10-year Treasury note and to 2.70 percent for the 10-year government bond of Germany by Fri Jul 15 because of the combination of weak economy in the US and renewed fears on Greece and other sovereigns in Europe. Section V Valuation of Risk Financial Assets provides more details and comparisons of performance in peaks and troughs.

The upper row in the stock indexes in Table 1 measures the percentage cumulative change since the closing level in the prior week on Jul 8 and the lower row measures the daily percentage change. Performance of equities markets was weak. The DJ Global index fell 1.4 percent in the week with the effects of the employment report in the US, additional weak economic reports and the doubts on highly-indebted countries in Europe with the DAX of Germany losing 2.5 percent in the week. The DJ Asia Pacific index fell 1.6 percent in the week.

The final block of Table 1 shows strong performance of gold and weak performance of the oil indexes. Brent lost 0.6 percent in the week even after gaining 1.1 percent on Fri Jul 15, and WTI gained 1.1 percent, gaining 1.6 percent on Fri Jul 15 after release of the bank stress tests in Europe. Increasing risk appetite appears to have stimulated the carry trade. Gold gained 3.3 percent by Fri Jul 15 with some investors believing gold can hedge adverse economic conditions.

Useful dimensions of the world, regions and individual countries are provided in Table 2. The IMF measures world output in 2010 at $57,920.3 billion of which $31,891.5 billion, or 55.1 percent, is contributed by the “major advanced economies,” or Group of 7 (G7), consisting of the Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (for the G7 see Pelaez and Pelaez, International Financial Architecture (2005), 63-96). There are four factors of financial uncertainty in the world economy originating in the regions and countries in Table 2.

Table 2, World and Selected Regional and Country GDP and Fiscal Situation

| GDP USD 2010 USD Billions | Primary Net Lending Borrowing % GDP 2010 | General Government Net Debt % GDP 2010 | |

| World | 57,920.3 | ||

| Euro Zone | 12,192.8 | -3.6 | 64.3 |

| Portugal | 229.3 | -4.6 | 79.1 |

| Ireland | 204.3 | -29.7 | 69.4 |

| Greece | 305.4 | -3.2 | 142.0 |

| Spain | 1,409.9 | -7.8 | 48.8 |

| Major Advanced Economies G7 | 31,891.5 | -6.9 | 74.4 |

| United States | 14,657.8 | -10.6 | 64.8 |

| UK | 2,247.5 | -8.6 | 69.4 |

| Germany | 3,315.6 | -3.3 | 53.8 |

| France | 2,582.5 | -7.7 | 74.6 |

| Japan | 5,458.9 | -9.5 | 117.5 |

| Canada | 1,574.1 | -5.5 | 32.2 |

| Italy | 2,055.1 | -4.6 | 99.6 |

| China | 5,878.3 | -2.6 | 17.7 |

Source: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/01/weodata/index.aspx

First, European sovereign risks. There are euro zone countries that are relatively sound in terms of fiscal situations and financial variables, especially spreads of sovereign bonds and government debts and deficits, such as France and Germany. Three euro zone countries have engaged in bailouts within the mechanism created by the European Union, IMF and European Central Banks: Portugal, Ireland and Greece. The combined GDPs of Portugal, Ireland and Greece add to $739 billion, which represents only 6.1 percent of the euro zone GDP of $12,192.8 billion, shown in Table 2. The problem is in the exposure of European banks to the bailed out countries and of banks worldwide to the bailed out countries and to the European banks. These exposures are much more important in relative terms of propagating financial stress than the combined GDP of the bailed out countries. The turmoil during the week of Jul 15 manifested in the form of increases in the sovereign bond spreads and declines in the stock markets and bank stocks of Spain and Italy. The addition of the GDP of Spain and Italy to the bailed-out countries totals $4204 billion, which is equivalent to 34.5 percent of euro zone GDP. There were three types of events in the week of Jul 15, 2011 that affected both the bailed out countries and Italy and Spain. (1) Moody’s Investors Service (2011Jul11) finds that there will not be open-ended or unlimited support for the bailed-out countries. The test for access to the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) and in the future from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is that countries must meet tests of solvency. In cases tests are not met, support is not immediate and requires participation of the private sector. Moody’s Investors Services (2011Jul11) finds that: “The prospect of any form of private sector participation in debt relief is obviously negative for holders of distressed sovereign debt. That increasingly negative outlook, alongside the challenges in achieving financial consolidation objectives, lies behind our recent downgrades of Greece and Portugal and our ongoing assessment of countries facing similar challenges.” Moody’s Investor Services (2011Jul12) “downgraded Ireland’s foreign- and local-currency government bond ratings by one notch to Ba1 from Baa3. The outlook of ratings remains negative.” The rationale for the downgrade is that Ireland may need further “official financing” when its program with the European Union and IMF ends at year-end 2013. Such official financing is being tied under the ESM by private sector participation that will be a negative for creditors. (2) Italy’s spreads of its sovereign bonds, stock market and bank market valuations oscillated during the week of Jul 15. David Cottle writing on Jul 12 on “Italy fears rattle Europe’s markets” published by the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303812104576441302547119220.html?mod=WSJPRO_hpp_LEFTTopStories) informs that Italy’s “total capital market debt” is €1598 billion, approximately $2.2 trillion, which is the largest in the euro zone and the third largest in the world after the US and Japan. There is a cushion in that only €88 billion mature in 2011 and €190 billion mature in 2012. Perhaps the major source of concern for propagation of turbulence in Italy is that French banks had $392.6 billion in Italian government and private debt at the end of 2010, according to Bank for International Settlements (BIS) data, as informed by Fabio Benedetti-Valentini, writing on Jul 12, 2011, on “French banks face greatest Italian risk” published by Bloomberg (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-07-12/france-s-bnp-credit-agricole-on-frontline-with-italian-risk.html). There is a funding test for Italian banks in 2012 as its two largest lenders have maturing debt of around €55.4 billion, as informed by Elisa Martinuzzi and Charles Penty writing on Jul 14 on “Italian banks face funding squeeze” published by Bloomberg (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-07-13/italian-banks-face-funding-squeeze-as-crisis-enters-new-phase.html). (3) The European Banking Authority released the stress tests of banks on July 15 with the following results (EBA 2011Jul15):

“Based on end 2010 information only, the EBA exercise shows that 20 banks would fall below the 5% CT1 threshold over the two-year horizon of the exercise. The overall shortfall would total EUR26.8 bn.

However, the EBA allowed specific capital actions in the first four months of 2011 (through the end of April) to be considered in the results. Banks were therefore incentivised to strengthen their capital positions ahead of the stress test.

Between January and April 2011 a further amount of some EUR50bn of capital was raised on a net basis.

Once capital-raising actions in 2011 are added, the EBA’s 2011 stress test exercise shows that eight banks fall below the capital threshold of 5% CT1R over the two-year time horizon, with an overall CT1 shortfall of EUR2.5bn. In addition, 16 banks display a CT1R of between 5% and 6%.”

Patrick Jenkins, Banking Editor of the Financial Times, writing on Jul 15 on “Banks’ stress tests pass rate under fire” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/dc111364-aefa-11e0-bb89-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1S4mkHrZz) raises the issue if the tests are robust enough to recover confidence on banks as only nine of the 91 banks tested had shortfalls of capital. An important result is the 16 banks with capital above 5 percent and below 6 percent. Thus, the total banks required to increase capital is 24 (EBA 2011PR). Guy Dinmore writing on Jul 15 on “Italian parliament passes €45 billion cuts package” published in the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/bbef9be0-aef6-11e0-bb89-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1S4mkHrZz) informs that the parliament of Italy approved an austerity package of €45 billion that will eliminate the government deficit by 2014 but the public debt of Italy reached a new high in May of €1900 billion (or about $2690 billion). Joshua Chaffin writing on Jul 15 on “Eurozone summit raises hopes for deal on Greece” published by the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/bac09dc2-af10-11e0-bb89-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1S4mkHrZz) informs that the leaders of the euro zone will participate in a summit on Jul 12 to find agreement on the second bailout of Greece together with measures for resolution of the widening sovereign debt problems in Europe.

Second, United States. Weakening economic conditions in the US in eight quarters of mediocre growth with 25 to 30 million people in job stress (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html) also create bouts of financial turbulence. Current discussions on increasing the limit of Treasury debt are generally expected to produce an agreement. In a rare event (Moody’s 2011Jul13):

“Moody’s Investors Service has placed the Aaa bond rating of the government of the United States on review for possible downgrade given the rising possibility that the statutory debt limit will not be raised on a timely basis, leading to a default on US Treasury obligations. In conjunction with this action, Moody’s has placed on review for possible downgrade the Aaa rating of financial institutions directly linked to the US government: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Home Loan Banks, and the Federal Farm Credit Banks. We have also placed on review for possible downgrade securities either guaranteed by, backed by collateral securities issued by, or otherwise directly linked to the US government or the affected financial institutions. The review of the US government’s bond rating is prompted by the possibility that the debt limit will not be raised in time to prevent a missed payment of interest or principal on outstanding bonds and notes. As such, there is a small but rising risk of a short-lived default.”

Moody’s (2011Jul13MC) separates municipal debt securities in two categories: (1) “directly linked Aaa credits” that “have been placed on review for possible downgrade, affecting more than 7,000 ratings (sale, debt or maturity level) with about $130 billion of original par amount” and will follow further rating actions on the US government; and (2) “indirectly linked Aaa credits” on which there are no “explicit guarantees or support from the US government.” The indirectly linked are being classified into “vulnerable” that will be classified for rating review and “resilient” that will not be classified for rating review.

Standard & Poor’s (2011Jul14) placed the US AAA long-term and A-1+ short term sovereign credit ratings on “CreditWatch with negative implications.” With the CreditWatch, Standard & Poor’s (2011Jul14) is signaling a chance of “one-in-two” that it could “lower the long-term rating on the US within the next 90 days.” The CreditWatch negative assignment is based on the view of significant uncertainty on the creditworthiness of the US. Standard & Poor’s (2011Jul14) finds that the political debate in the US after two months of negotiation on the debt ceiling has “only become more entangled” in a confrontation of views on fiscal policy. There is risk, according to Standard & Poor’s (2011Jul14), of the “policy stalemate enduring beyond any near-term agreement to raise the debt ceiling.” As a result, S&P finds that it may lower the ratings in the next three months. If there is no agreement between Congress and the Administration on “a credible solution to the rising US government debt burden,” Standard and Poor’s (2011Jul14) could “lower the long-term rating on the US by one or more notches into the ‘AA’ category in the next three months.” The risks of “payment default” on US debt are “small” but “increasing.” Brief default could force classification by S&P of US debt in “selective default” or “SD,” which means that the US would default some but not all debt obligations while continuing current in the remaining debt obligations.

The US is facing a tough budget/debt quagmire. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2011LTBO) extends the projections of the US budget beyond the ten-year window in terms of two scenarios. (1), Table 3 provides projections of the budget and debt for the “extended-baseline scenario,” which is based on the following assumptions (CBO 2011LTBO, 2):

“The current-law assumption of the extended-baseline scenario implies that many adjustments that lawmakers have routinely made in the past—such as changes to the AMT and to the Medicare program’s payments to physicians—will not be made again. Because of the structure of current tax law, federal revenues would grow significantly faster than GDP over the long run under this scenario, ultimately rising well above the levels that U.S. taxpayers have seen in the past.”

Table 3, CBO Long-term Budget Outlook Extended-Baseline Scenario, % of GDP

| 2011 | 2021 | 2035 | |

| Spending | 24.1 | 23.9 | 27.4 |

| Primary | 22.7 | 20.5 | 23.3 |

| SS | 4.8 | 5.3 | 6.1 |

| Medicare | 3.7 | 4.1 | 5.9 |

| Medicaid | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Other | 12.3 | 8.3 | 7.8 |

| Interest | 1.4 | 3.4 | 4.1 |

| Revenues | 14.8 | 20.8 | 23.2 |

| Deficit | –9.3 | -3.1 | -4.2 |

| Primary | –7.9 | 0.3 | -0.1 |

| Debt | 69 | 76 | 84 |

Primary spending is spending other than interest payments. Primary deficit or surplus is revenue less primary spending.

Source: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/122xx/doc12212/06-21-Long-Term_Budget_Outlook.pdf

The scenarios require assumptions about economic variables, in particular “real wage growth for workers covered by social security, growth in consumer price index, nominal wage growth for workers covered by social security, average real annual interest rate, average annual unemployment rate and real GDP” (CBO 2011LTBO Excel worksheet). Table 3 provides spending divided in primary spending and interest payments and the resulting concepts of primary balance equal to revenue less primary spending and total balance or revenue less total spending. Debt held by the public increases from 69 percent of GDP in 2011, much higher than 40 percent of GDP in 2008, to 76 percent of GDP in 2021 and 84 percent of GDP in 2035. Albert Einstein is attributed phrases such as “compound interest is the greatest mathematical discovery of all time” and “the most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” An important aspect of Table 3 is that interest payments on the debt held by the public increase from 1.4 percent of GDP in 2011 to 3.4 percent of GDP in 2021 and to 4.1 percent of GDP in 2035. Spending on categories other than social security, Medicare and Medicaid shrinks from 12.3 percent of GDP in 2011 to 8.3 percent of GDP in 2021 and to 7.8 percent in 2035.

Correspondingly, the combined share of social security, Medicare and Medicaid in spending increases from 10.4 percent of GDP in 2011 to 15.5 percent of GDP in 2035 with combined Medicare and Medicaid explaining most of the increase with a jump from 5.6 percent of GDP to 9.4 percent of GDP while social security only increases its share from 4.8 percent of GDP in 2011 to 6.1 percent in 2035. Revenue as a percent of GDP has been on average 18.6 percent in the past 40 years and there is skepticism if it can increase above 20 percent of GDP. The alternative-baseline scenario in Table 3 projects revenue as percent of GDP at 20 percent of GDP in 2015 and 2016 and then exceeding 20 percent permanently, rising to 30.6 percent of GDP in 2085 (see the Excel spreadsheet accompanying CBO 2011LTBO).

(2), Table 4 provides fiscal projections under an alternative fiscal scenario, which is based on the following assumptions (CBO 2011LTBO, 2):

“The alternative fiscal scenario embodies several changes to current law that would continue certain tax and spending policies that people have grown accustomed to (because the policies are in place now or have been in place recently). Versions of some of the changes assumed in the scenario—such as those related to the tax cuts originally enacted in 2001, the AMT, certain other tax provisions, and Medicare’s payments to physicians—have regularly been enacted in the past and are widely expected to be made in some form over the next few years. After 2021, the alternative fiscal scenario also incorporates modifications to several provisions of current law that might be difficult to sustain for a long period. Thus, the scenario includes changes to certain restraints on the growth of spending for Medicare and to indexing provisions that would slow the growth of federal subsidies for health insurance coverage. In addition, the scenario includes unspecified changes in tax law that would keep revenues constant as a share of GDP after 2021.”

Table 4, CBO Long-term Budget Outlook Alternative Fiscal Scenario, % of GDP

| 2011 | 2021 | 2035 | |

| Spending | 24.1 | 25.9 | 33.9 |

| Primary | 22.7 | 21.5 | 25.0 |

| SS | 4.8 | 5.3 | 6.1 |

| Medicare | 3.7 | 4.3 | 6.7 |

| Medicaid | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Other | 12.3 | 9.1 | 8.5 |

| Interest | 1.4 | 4.4 | 8.9 |

| Revenues | 14.8 | 18.4 | 18.4 |

| Deficit | -9.3 | -7.5 | -15.5 |

| Primary | -7.9 | -3.1 | -6.6 |

| Debt | 69 | 101 | 187 |

Primary spending is spending other than interest payments. Primary deficit or surplus is revenue less primary spending.

Source: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/122xx/doc12212/06-21-Long-Term_Budget_Outlook.pdf

An important distinguishing characteristic of the alternative fiscal scenario in Table 4 is the much sharper increase in debt held by the public from 69 percent of GDP in 2011 to 101 percent of GDP in 2021 and 187 percent of GDP in 2035. Accordingly, interest payments on the debt jump from 1.4 percent of GDP in 2011 to 8.9 percent of GDP in 2035. In contrast with the extended-baseline scenario, the alternative fiscal scenario fixes revenue as percent of GDP at 18.4 percent after 2035.

Fiscal projections by the CBO incorporate a host of assumptions on demographic variables, such as the rate of growth and consumption of the US population, economic variables, interest rates, labor market factors, real GDP and earnings per worker. The CBO (2011LTBO) analyzes how the performance of the economy would be affected by an increase in debt held by the public over 76 percent of GDP, which is used as benchmark economic conditions. A Solow-type model (after Solow 1956, 1989; see Pelaez and Pelaez, Globalization and the State, Vol. I (2008a), 11-16) is used for measuring effects on the economy of fiscal policies under the two scenarios. The method is discussed in CBO (2011PBB, Appendix A, 31-7). The calculations by the CBO (2011LTO, 28-31) are shown in Table 5. The impact is much softer on GDP than on GNP because “the change in GDP does not reflect the increased future outflow of profits and interest generated by the additional capital inflow” (CBO 2011LTO, 28). The striking result in Table 11 is the sharp reduction of GNP by 2035 of 6.7 percentage points to 17.6 percentage points over what it would be under the benchmark debt level of 76 percent and of GDP from 2.4 percentage points to 9.9 percentage points.

Table 5, Effects on GNP and GDP of Fiscal Policies in CBO’s Scenarios in Percentage Difference from Benchmark Level

| 2025 | 2035 | |

| Extended Baseline | ||

| GNP | -0.2 to –0.4 | -0.5 to –1.6 |

| GDP | (-0.05 to 0.05 to –0,2 | -0.2 to –1.3 |

| Alternative Fiscal | ||

| GNP | -2.2 to –5.7 | -6.8 to –17.6 |

| GDP | -0.4 to –3.1 | -2.4 to –9.9 |

Source: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/122xx/doc12212/06-21-Long-Term_Budget_Outlook.pdf

Two alternative strands of thought on policies for the current slow growth and weak hiring are considered in an earlier comment (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011_06_01_archive.html). Summers (2011Jul12) argues in an article in the Financial Times that a budget deal increasing GDP by 1 percent that will slowly disappear to 0 percent during a decade would increase GDP by 0.5 percent in the decade, representing 4 million job years and government revenue of $400 billion. In this view, the economy is in a liquidity trap because of the near-zero policy interest rate such that fiscal policy would have more than normal effects. Summers (2011Jul12) argues that a budget deal with continuing reductions of payroll taxes, extended unemployment benefits and infrastructure maintenance could add 2 percent to GDP. Timing is critical and the budget deal should be pushed forward immediately. Blinder (2011Jul12) in an article in the Wall Street Journal finds that the US has a national employment emergency. Adjusting the budget should be a task after solving the jobs problem. There are no magical solutions to this problem, according to Blinder (2011Jul12), not costless ones in the form of the inexistent free lunch. There are expenses in job creation either by reducing taxes or increasing expenditures. Blinder (2011Jul12) proposes the marrying of a “new jobs tax credit” with tax incentives for repatriation of profits held abroad by corporations. In his example, a corporation paying $1.5 billion in wages under Social Security would receive a tax credit for repatriation of profits if it increased the wages paid under Social Security by $100 million to $1.6 billion. The $100 million of repatriated profits held abroad would pay taxes at the rate of 5 to 10 percent instead of the usual corporate rate of 35 percent. The company would save between $25 million to $30 million and would have a powerful incentive to create jobs.

Reinhart and Rogoff (2011Jul14) provide succinct analysis of their new research on debt (Reinhart and Rogoff 2011CEPR with references to new research), extending their now classic monumental research on financial crisis (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009TD). Their database consists of public debt for 44 countries in about 200 years with 3700 observations of multiple relevant variables including central government balances. Economic models consist of structures or systems of simultaneous equations but data are observed under the influence of many variables such that identifying causes and effects is quite difficult. Reinhart and Rogoff (2011CEPR, 2011Jul14) concludes that there is a threshold approximately around 90 percent of GDP above which higher debt inhibits economic growth. There are relatively few cases of debt/GDP ratios above 90 percent of GDP and even fewer above 120 percent of GDP. It is quite likely that when debt reaches a point of explosion pressure mounts on politicians to increase taxes, reduce expenditures and rely on inflation or financial repression to reduce debt/GDP ratios. The conclusion of this monumental research is that debt/GDP explosions are as important in the current environment as in other circumstances in the past.

Third, natural disasters and geopolitical events. A critical natural disaster was the earthquake/tsunami of Japan on Mar 11 that not only caused significant harm to the country but also supply chain disruptions worldwide. An important geopolitical event was regime change movements in the Middle East.

Fourth, China tradeoff of growth and inflation. Financial turbulence has also originated in increasing inflation in China with threats to the country’s economic growth. There is discussion of this other financial vulnerability below in Section III Global Inflation.

II Hiring Collapse. An appropriate measure of job stress is considered by Blanchard and Katz (1997, 53):

“The right measure of the state of the labor market is the exit rate from unemployment, defined as the number of hires divided by the number unemployed, rather than the unemployment rate itself. What matters to the unemployed is not how many of them there are, but how many of them there are in relation to the number of hires by firms.”

The natural rate of unemployment and the similar NAIRU are quite difficult to estimate in practice (Ibid; see Ball and Mankiw 2002).

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) created the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) with the purpose that (http://www.bls.gov/jlt/jltover.htm#purpose):

“These data serve as demand-side indicators of labor shortages at the national level. Prior to JOLTS, there was no economic indicator of the unmet demand for labor with which to assess the presence or extent of labor shortages in the United States. The availability of unfilled jobs—the jobs opening rate—is an important measure of tightness of job markets, parallel to existing measures of unemployment.”

The BLS collects data from about 16,000 US business establishments in nonagricultural industries through the 50 states and DC. The data are released monthly and constitute an important complement to other data provided by the BLS.

Hiring in the nonfarm sector (HNF) has declined from 64.9 million in 2006 to 47.2 million in 2010 or by 17.7 million while hiring in the private sector (HP) has declined from 60.4 million in 2006 to 43.3 million in 2010 or by 17.1 million, as shown in Table 6. The ratio of nonfarm hiring to unemployment (RNF) has fallen from 47.7 in 2006 to 36.4 in 2010 and in the private sector (RHP) from 52.9 in 2006 to 40.3 in 2010 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/slow-growth-inflation-unemployment-and.html).

Table 6, Annual Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US and Percentage of Total Employment

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 | 63,766 | 48.4 | 59,374 | 53.6 |

| 2002 | 59,797 | 45.9 | 55,665 | 51.1 |

| 2003 | 57,787 | 44.5 | 54,082 | 49.9 |

| 2004 | 61,624 | 46.9 | 57,534 | 52.4 |

| 2005 | 64,498 | 48.2 | 60,444 | 54.0 |

| 2006 | 64,870 | 47.7 | 60,419 | 52.9 |

| 2007 | 63,326 | 46.0 | 58,760 | 50.9 |

| 2008 | 53,986 | 39.5 | 50,286 | 44.0 |

| 2009 | 45,372 | 34.7 | 41,966 | 38.8 |

| 2010 | 47,234 | 36.4 | 43,299 | 40.3 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

Table 7 provides total HNF and HP in the month of May from 2001 to 2011. An important characteristic of the labor market in the US is that HNF has declined from 6.010 million in May 2006 to 4.531 million in May 2011, or by 1.479 million, and HP has fallen from 5.631 million in May 2006 to 4.250 million in May 2011, or by 1.381 million. HNF of 4.531 million in May 2011 is almost unchanged relative to 4.746 million in May 2010 and HP in May 2011 of 4.250 million is lower by 1.256 million than 5.506 million in May 2001. The US labor market is fractured, creating fewer opportunities to exit job stress of unemployment and underemployment of 25 to 30 million people and declining inflation-adjusted wages in the midst of fast increases in prices of everything (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/unemployment-and-underemployment-of-24.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/job-stress-of-24-to-30-million-falling.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/twenty-four-to-thirty-million-in-job_03.html).

Table 7, Total Nonfarm Hiring (HNF) and Total Private Hiring (HP) in the US in Thousands and in Percentage of Total Employment in May Not Seasonally Adjusted

| HNF | Rate RNF | HP | Rate HP | |

| 2001 May | 5898 | 4.4 | 5506 | 4.9 |

| 2002 May | 5434 | 4.1 | 5065 | 4.6 |

| 2003 May | 5093 | 3.9 | 4794 | 4.4 |

| 2004 May | 5486 | 4.2 | 5183 | 4.7 |

| 2005 May | 5775 | 4.3 | 5444 | 4.9 |

| 2006 May | 6010 | 4.4 | 5631 | 4.9 |

| 2007 May | 5836 | 4.2 | 5421 | 4.7 |

| 2008 May | 5135 | 3.7 | 4816 | 4.2 |

| 2009 May | 4186 | 3.2 | 3906 | 3.6 |

| 2010 May | 4746 | 3.6 | 3398 | 3.7 |

| 2011 May | 4531 | 3.4 | 4250 | 3.9 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/jlt/data.htm

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) also calculates alternative measures of labor underutilization for the US and all states. Table 8 shows six measure of underutilization described in the note. There is dramatic rise in the broad measure of labor underutilization, U6, or total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons as percent of the labor force plus all marginally attached workers. This blog provides the numerator of U6 after the release of every employment situation report by the BLS. The number for Jun is 25.319 million in job stress (see Table 1 in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/unemployment-and-underemployment-of-24.html) but using a different rate of participation of the population in the labor force the number could be 29.693 million (see Table 2 and discussion in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/unemployment-and-underemployment-of-24.html).

Table 8, Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization %

| U1 | U2 | U3 | U4 | U5 | U6 | |

| IIQ10 to IQ11 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 16.5 |

| 2010 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 16.7 |

| 2009 | 4.7 | 5.9 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.5 | 16.2 |

| 2008 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 10.5 |

| 2007 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 8.3 |

| 2006 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.6 |

Note: LF: labor force; U1, persons unemployed 15 weeks % LF; U2, job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs %LF; U3, total unemployed % LF; U4, total unemployed plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers; % LF plus discouraged workers; U5, total unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers % LF plus all marginally attached workers; U6, total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons % LF plus all marginally attached workers

Source: http://www.bls.gov/lau/stalt11q1.htm

Seasonally-adjusted measures of labor underutilization for Jun 2010 and Feb to Mar 2011 are provided in Table 9. The more comprehensive measure is U6 consisting of total unemployed plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part-time for economic reasons as percent of the labor force plus all marginally attached workers. U6 has increased SA from 15.9 in Feb 2011 to 16.2 in Jun 2011.

Table 9, Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization SA %

| Jun 2010 | Feb 2011 | Mar 2011 | Apr 2011 | May 2011 | Jun 2011 | |

| U1 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| U2 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| U3 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 9.2 |

| U4 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.8 |

| U5 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.7 |

| U6 | 16.5 | 15.9 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 15.8 | 16.2 |

Note: LF: labor force; U1, persons unemployed 15 weeks % LF; U2, job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs %LF; U3, total unemployed % LF; U4, total unemployed plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers; % LF plus discouraged workers; U5, total unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers % LF plus all marginally attached workers; U6, total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons % LF plus all marginally attached workers

Source: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

An article in Real Time Economics of the Wall Street Journal on Jul 16 on “Number of the week: 5% unemployment could be a decade away” (http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2011/07/16/number-of-the-week-5-unemployment-could-be-over-a-decade-away/) provides an approximation of the number of months that would be required for the economy to return to the 5 percent unemployment rate of 2007. The current unemployment rate for Jun is 9.2 percent, with 14.1 million unemployed, on the basis of the household survey. Job creation in the first half of 2011 was 757,000 jobs, on the basis of the establishment survey. Assuming that job creation is approximately the same in the household survey as in the establishment survey, there would be a gain of 1.6 million new jobs in the year forward from Jun 2011 to Jun 2012. Real Time Economics adds to the calculation the growth of the labor force projected by the Census as 1.4 million people aged 16 and over. Employment would grow by 1.6 million while the labor force would grow by 1.4 million, reducing unemployment by only 200,000 that would still leave the rate of unemployment at 8.9 percent. Under those assumptions about employment growth and labor force growth, the rate of unemployment of 5 percent would only be attained in Dec 2024. Another recession would create a setback in the calculations. Another issue is that there appears to be an additional 4 million unemployed who are not counted because they abandoned the hope of finding another job, such that the total unemployment in Jun is more likely to be closer to 18.4 million. To that would have to be added 8.6 million barely making a living in part-time jobs because they cannot find anything better and 2.7 million marginally attached to the labor force. The total number of people in job stress in the US is 29.693 million in Jun 2011 (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html). The US is suffering a suffocating unemployment and underemployment stress that would require much faster growth than that experienced in the weakest recovery from a recession since World War II.

II Global Inflation. There is inflation everywhere in the world economy, with slow growth and persistently high unemployment in advanced economies. The JP Morgan Global PMI, compiled by Markit, provides an important reading of the world economy, analyzed by Markit’s Chief Economist Chris Williamson (http://www.markit.com/assets/en/docs/commentary/markit-economics/2011/jul/global_economy_11_07_07.pdf). The JP Morgan Global PMI, compiled by Markit, registered the weakest quarter of private sector output growth in manufacturing and services since IIIQ2009, when the world economy began recovering, falling from 52.7 in May to 52.2 in Jun. Japan recovered sharply from the Mar earthquake/tsunami but the JP Morgan Global PMI compiled by Markit shows that the index is significantly lower in Jun than in May, being consistent with world GDP growth at the low annual rate of 2 percent. Japan’s sharp recovery has been compensated in the index by weak IIQ2011 growth in the US, with Jun being at the lowest in 22 months, and similar weakness in the euro zone and the UK. Growth has also weakened in the BRIC countries of Brazil, Russia, India and China. The JP Morgan Global PMI compiled by Markit shows that world manufacturing exports have nearly stagnated with the worst performance since Jul 2009. The softness of the economy is worldwide and persistent.

Table 10 updated with every post, provides the latest annual data for GDP, consumer price index (CPI) inflation, producer price index (PPI) inflation and unemployment (UNE) for the advanced economies, China and the highly-indebted European countries with sovereign risk issues. The table now includes the Netherlands and Finland that with Germany make up the set of northern countries in the euro zone that hold key votes in the enhancement of the mechanism for solution of the sovereign risk issues (http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/55eaf350-4a8b-11e0-82ab-00144feab49a.html#axzz1G67TzFqs). Aaron Back and Jason Dean writing on Jul 9, 2011 on “China price watchers predict another peak” published in the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304793504576433443699064616.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection) inform that China’s CPI inflation jumped to 6.4 per cent in Jun relative to a year earlier, much higher than 5.5 percent in May but many economists believe that inflation could decline in the second half of the year. Comparisons with high rates of CPI inflation late in 2010 will likely result in lower 12 months rates of inflation later in 2011. Jamil Anderlini writing on Jul 9, 2011, on “China inflation hits three-year high” published by the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/693daad2-aa1d-11e0-958c-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Repz5K5o) informs that food prices increased 14.4 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun. Core non-food prices increased 3 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun, which is the highest rate in five years, suggesting inflation is spreading in the economy. Headline CPI inflation rose 0.3 percent in Jun relative to May but prices excluding food were stable, which could signal decelerating inflation. Aaron Back writing on Jul 6, 2011 on “China raises interest rates” published by the Wall Street Journal Asia Business (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303544604576429393824293666.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection) informs that the People’s Bank of China raised the one-year lending rate from 6.31 percent to 6.56 percent and the one-year deposit rate to 3.5 percent from 3.25 percent. This was the fifth increase in interest rates in 2010 and 2011. The People’s Bank of China has raised the reserve requirements of banks six times in 2011. The concern with inflation in China is that it could be a factor in a “hard landing” of the economy with growth lower than 7 percent. The lending rate may not be negative in real terms if during the next 12 months inflation falls below the yearly rate of 6.5 percent. An issue is China is the use of generous credit growth to prevent the impact of the global recession on China. Deposit rates of 3.5 percent are likely to be lower than forward inflation, stimulating the purchase of speculative assets such as housing and also goods that may rise more than expected inflation. Martin Vaughan writing on July 5, 2011 on “Moody’s warns on China debt” published by the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304803104576427062691548064.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection) informs of the warning by Moody’s Investors Service that China’s National Audit Office (NAO) understated CNY 3.5 trillion or $541 billion of bank loans to local governments. That portion of loans has poor documentation and highest exposure to delinquencies. NAO has concluded that banks have lent CNY 8.5 trillion to local government. A critical issue in China is the percentage of those loans that could become nonperforming and the impact that could occur on bank capital and solvency. The report by Moody’s Investors Service “estimates that the Chinese banking system’s economic nonperforming loans could reach between 8% and 12% of total loans, compared to 5% to 8% in the agency’s base case, and 10% to 18% in its stress case” (http://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Scale-of-problem-loans-to-Chinese-local-governments-greater?lang=en&cy=global&docid=PR_222068). A hard landing in China could have adverse repercussions in the regional economy of Asia and throughout the world’s financial markets and economy. The combination of a hard landing in China with sovereign risk difficulties in Europe and further slowing of the US economy could have strong, unpredictable effects. Jamil Anderlini writing from Shanghai on Jul 10, 2011 on “Trade data show China economy slowing” published by the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/eeedc000-aabc-11e0-b4d8-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Repz5K5o) informs that Chinese imports grew at 19.3 percent in June 2011 relative to Jun 2010, which is significantly below the 12-month rate of 28.4 percent in May. China’s industrial activity appears to be decelerating as suggested by lower imports of commodities such as crude oil, aluminum and iron ore, all falling in the 12 months ending in Jun 2011. China’s imports of crude oil fell 11.5 percent in Jun 2011 relative to Jun 2010 and copper imports grew in Jun but were lower than a year earlier. China’s exports grew 17.9 percent in Jun from a year earlier to a monthly record of $162 billion. The trade surplus of China in Jun of $22.3 billion was higher than $13 billion in May and may reignite the complaints about China’s exchange rate policy. Simon Rabinovitch writing on Jul 12 on “China’s foreign reserves climb by $153 billion” published by the Financial Times (http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/13c382e6-ac59-11e0-bac9-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Repz5K5o) informs that China’s foreign reserves rose by $153 billion in IIQ2011 after increasing $197 billion in IQ2011, reaching $3197 billion, which is around 50 percent of GDP and three times higher than reserves by any other country. The trade surplus contributed $47 billion of the increase of reserves of $153 billion in IIQ2011 with the remainder originating mostly in investment inflows and interest earnings. Aaron Back writing on Jul 13 on “China growth suggests tightening ahead” published by the Wall Street Journal (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304223804576443493415667206.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection) analyzes new data on China showing fast expansion of the economy that could signal further tightening measures. China’s GDP grew at 9.5 percent in IIQ2011, which is lower than 9.7 percent in IQ2011. Most countries report GDP growth as seasonally adjusted quarterly rates converted in annual equivalent. The adjustment of Chinese data for seasonality in annual equivalent results in GDP growth of 9.1 in IIQ2011 compared with 8.7 percent growth in IQ2011. The growth rate of GDP of China in IIQ2011 increased slightly to 2.2 percent in that quarter. Industrial production rose to the 12-month rate in Jun of 15.1 percent, which is higher than 13.3 percent in May. Real estate investment in Jan-Jun 2011 rose to CNY 2.625 trillion, equivalent to about $405 billion, which is higher by 32.9 percent relative to Jan-Jun 2010. Sales of commercial and residential property sales in Jan-Jun 2011 rose 24.1 percent relative to 2010, which is higher than 18.1 percent in Jan-May

Table 10, GDP Growth, Inflation and Unemployment in Selected Countries, Percentage Annual Rates

| GDP | CPI | PPI | UNE | |

| US | 2.9 | 3.6 | 7.0 | 9.2 |

| Japan | -0.7*** | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.5 |

| China | 9.5 | 6.4 | 6.8 | |

| UK | 1.8 | 4.5* | 5.7* output | 7.7 |

| Euro Zone | 2.5 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 9.9 |

| Germany | 4.8 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| France | 2.2 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 9.5 |

| Nether-lands | 3.2 | 2.5 | 10.7 | 4.2 |

| Finland | 5.8 | 3.4 | 8.0 | 7.8 |

| Belgium | 3.0 | 3.4 | 9.7 | 7.3 |

| Portugal | -0.7 | 3.3 | 5.9 | 12.4 |

| Ireland | -1.0 | 1.2 | 5.3 | 14.0 |

| Italy | 1.0 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 8.1 |

| Greece | -4.8 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 15.1 |

| Spain | 0.8 | 3.0 | 6.7 | 20.9 |

Notes: GDP: rate of growth of GDP; CPI: change in consumer price inflation; PPI: producer price inflation; UNE: rate of unemployment; all rates relative to year earlier

*Office for National Statistics

PPI http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/ppi0711.pdf

CPI http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/cpi0611.pdf

** Excluding food, beverage, tobacco and petroleum

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/4-04042011-AP/EN/4-04042011-AP-EN.PDF

***Change from IQ2011 relative to IQ2010 http://www.esri.cao.go.jp/jp/sna/sokuhou/kekka/gaiyou/main_1.pdf

Source: EUROSTAT; country statistical sources http://www.census.gov/aboutus/stat_int.html

Stagflation is still an unknown event but the risk is sufficiently high to be worthy of consideration (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/risk-aversion-and-stagflation.html). The analysis of stagflation also permits the identification of important policy issues in solving vulnerabilities that have high impact on global financial risks. There are six key interrelated vulnerabilities in the world economy that have been causing global financial turbulence: (1) sovereign risk issues in Europe resulting from countries in need of fiscal consolidation and enhancement of their sovereign risk ratings (see Section I Financial Risk Aversion in this post, section IV in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/risk-aversion-and-stagflation.html and Section I Increasing Risk Aversion in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/increasing-risk-aversion-analysis-of.html and section IV in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/budget-quagmire-fed-commodities_10.html); (2) the tradeoff of growth and inflation in China; (3) slow growth (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/06/financial-risk-aversion-slow-growth.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/slowing-growth-global-inflation-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/mediocre-growth-world-inflation.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011_03_01_archive.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/mediocre-growth-raw-materials-shock-and.html), weak hiring (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/slow-growth-inflation-unemployment-and.html and section III Hiring Collapse in http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/fed-commodities-price-shocks-global.html ) and continuing job stress of 24 to 30 million people in the US and stagnant wages in a fractured job market (http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/07/twenty-five-to-thirty-million.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/05/job-stress-of-24-to-30-million-falling.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/04/twenty-four-to-thirty-million-in-job_03.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/unemployment-and-undermployment.html); (4) the timing, dose, impact and instruments of normalizing monetary and fiscal policies (see http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-there-second-act-of-us-great.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/global-financial-risks-and-fed.html http://cmpassocregulationblog.blogspot.com/2011/02/policy-inflation-growth-unemployment.html) in advanced and emerging economies; (5) the earthquake and tsunami affecting Japan that is having repercussions throughout the world economy because of Japan’s share of about 9 percent in world output, role as entry point for business in Asia, key supplier of advanced components and other inputs as well as major role in finance and multiple economic activities (http://professional.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704461304576216950927404360.html?mod=WSJ_business_AsiaNewsBucket&mg=reno-wsj); and (6) the geopolitical events in the Middle East.

Table 11 provides the forecasts of the Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents for the FOMC meeting in Jun. Inflation by the price index of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) was forecast for 2011 in the Apr meeting of the FOMC between 2.1 to 2.8 percent. Table 12 shows that the interval has narrowed to PCE headline inflation of between 2.3 and 2.5 percent. The FOMC focuses on core PCE inflation, which excludes food and energy. The Apr forecast of core PCE inflation was an interval between 1.3 and 1.6 percent. Table 11 shows the revision of this forecast in Jun to a higher interval between 1.5 and 1.8 percent. The Statement of the FOMC meeting on Jun 22 analyzes inflation as follows (http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20110622a.htm):

“Inflation has moved up recently, but the Committee anticipates that inflation will subside to levels at or below those consistent with the Committee's dual mandate as the effects of past energy and other commodity price increases dissipate. However, the Committee will continue to pay close attention to the evolution of inflation and inflation expectations.

To promote the ongoing economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with its mandate, the Committee decided today to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent. The Committee continues to anticipate that economic conditions--including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run--are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate for an extended period.”

Table 11, Forecasts of PCE Inflation and Core PCE Inflation by the FOMC, %

| PCE Inflation | Core PCE Inflation | |

| 2011 | 2.3 to 2.5 | 1.5 to 1.8 |

| 2012 | 1.5 to 2.0 | 1.4 to 2.0 |

| 2013 | 1.5 to 2.0 | 1.4 to 2.0 |

| Longer Run | 1.7 to 2.0 |

Source: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20110622.pdf

Japan’s corporate goods price index (CGPI), formerly wholesale price index (WPI), fell 0,1 percent in Jun, after falling 0.1 percent in May but increasing in all months in Jan-Apr. The annual equivalent rate of price increase in Jan-Jun is 4.1 percent and 2.5 percent year-on-year, as shown in Table 12. These are very high rates of price increase for Japan.

Table 12, Japan Corporate Goods Price Index (CGPI) ∆%

| Month | Year | |

| Jun | -0.1 | 2.5 |

| May | -0.1 | 2.2 |

| Apr | 0.9 | 2.5 |

| Mar | 0.6 | 2.0 |

| Feb | 0.2 | 1.7 |

| Jan | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| AE ∆% | 4.1 |

AE: annual equivalent

Source: http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/pi/cgpi_release/cgpi1106.pdf

Table 13 shows the euro area’s harmonized index of consumer prices (HIPC). The change in Jun 2011 relative to Jun 2010 is 2.7 percent. HIPC inflation has stabilized around 2.7 to 2.8 percent in the months of Apr to Jun 2011 relative to a year earlier. Core inflation, excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco, is 1.8 percent for the 12 months ending in Jun and has been at that rate in the quarter Apr to Jun 2011 relative to a year earlier. Energy prices have been rising much faster in the consumption basket of the HIPC, moderating slightly to 10.9 percent in Jun and 11.1 percent in May compared with 12.5 percent in Apr and 13.0 percent in Mar. Housing and transportation have been experiencing higher inflation for consumers than food. The 12 months HIPC is the inflation indicator for the European Central Bank with target of maximum 2 percent, explaining the recent interest rate increases. Table 10 above uses HIPC data for the euro zone and its member countries as provided by Eurostat.

Table 13, Euro Area Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices 12 Months ∆%

| Jun 11 /Jun 10 | May 11 /May 10 | Apr 11 /Apr 10 | |

| All | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| Ex Energy, Food, Alcohol and Tobacco | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Energy | 10.9 | 11.1 | 12.5 |

| Food | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| Housing | 4.8 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| Transport | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

Source: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/2-16062011-BP/EN/2-16062011-BP-EN.PDF

Table 14 provides consumer price index inflation in the UK. Inflation fell to 4.2 percent in Jun from 4.5 percent in the 12 months ending in Apr and May 2011, somewhat higher than 4.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Jan. The annual equivalent inflation in Jan-Jun, or what inflation would be in a full year if the cumulative rate in the first six months were repeated, is 4.5 percent, slightly higher than past 12 month inflation of 4.2 percent. The monthly rate dropped significantly from 1.0 percent in Apr to 0.2 percent in May and decline of 0.1 percent in Jun.

Table 14, UK Consumer Price Index ∆%

| Month | 12 Months | |

| Jun | -0.1 | 4.2 |

| May | 0.2 | 4.5 |

| Apr | 1.0 | 4.5 |

| Mar | 0.3 | 4.0 |

| Feb | 0.7 | 4.4 |

| Jan | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| Jan-May AE ∆% | 4.5 |

AE: annual equivalent

Surce: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/cpi0711.pdf

CPI inflation has risen moderately in France as shown in Table 15. The 12-month rate of 2.1 percent in Jun is only slightly higher than 1.8 percent in Jan. Much of the increase in inflation occurred in the quarter of Feb to Apr when energy and commodity prices were accelerating. Because of the rise in the quarter of Feb to Apr, the annual equivalent inflation rate in the first half of the year is 3.2 percent.

Table 15, France, Consumer Price Index ∆%

| Month | 12 Months | |

| Jun | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| May | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Apr | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| Mar | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| Feb | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Jan | -0.2 | 1.8 |

| AE ∆% | 3.2 |

Source: http://www.insee.fr/en/themes/info-rapide.asp?id=29&date=20110712

CPI inflation in Germany rose from 1.7 in the 12 months ending in Dec 2010 to 2.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2011, as shown in Table 16. Inflation was also higher in the quarter Feb to Apr as a result of commodity price increases but the rate fell significantly in the quarter Apr to June. The annual equivalent rate for the first six months of the year is 1.8 percent, which is lower than 2.3 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun.

Table 16, Germany, Consumer Price Index ∆%

| Month | 12 Months | |

| Jun | 0.1 | 2.3 |

| May | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Apr | 0.2 | 2.4 |

| Mar | 0.5 | 2.1 |

| Feb | 0.5 | 2.1 |

| Jan | -0.4 | 2.0 |

| Dec 2010 | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| AE ∆% | 1.8 |

CPI inflation in Italy has been relatively higher than in France and Germany, as shown in Table 17. There is the same collapse of the monthly rate in Jun and May, caused by the decline in commodity prices. There was an increase in monthly inflation in Jan of 0.4 percent instead of a decline as in France and Germany. The 12-month rate of inflation has jumped from 1.9 percent in Dec 2010 to 2.7 percent in Jun 2011.

Table 17, Italy, Consumer Price Index ∆%

| Month | 12 Months | |

| Jun | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| May | 0.1 | 2.6 |

| Apr | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Mar | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| Feb | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| Jan | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Dec 2010 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| AE ∆% | 3.7 |

CPI inflation is accelerating in the US as suggested by data in Table 18. The 12-month rate of increase of the CPI was 3.6 percent in Jun compared with an annual equivalent of 3.7 percent in Jan-Jun 2011. The 12-month rate of increase of the CPI in Dec 2010 was 1.5 percent and the average CPI rose 1.6 percent in 2010 relative to 2009. The 12-month rate of increase of the CPI in Dec 2007 was 4.1 percent and the average CPI rose 2.8 percent in 2007 relative to 2006 (ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiai.txt). The earlier “fear of deflation” in 2003-2004 that motivated near-zero interest rates ended in much higher inflation than 1.9 percent in the 12 months ending in Dec 2003 and 2.3 percent in the average of 2003 relative to 2002. The CPI excluding food and energy is rising less rapidly at 1.6 percent in 12 months but 2.6 percent annual equivalent in the first five months of 2011. The 12 months rates of increases are quite high for numerous items showing that commodity shocks have not been transitory but have occurred on a trend for nearly a year. The lowest increases in 12 months are for apparel, 1.0 percent, shelter 1.2 percent, and services less energy 1.6 percent. With the exception of energy, gasoline and transportation services, restrained by collapse of energy and commodity prices, annual equivalent rates for the first six months of 2011 exceed 12 months rates of increase.

Table 18, Consumer Price Index Percentage Changes 12 months NSA and Annual Equivalent Jan-Jun 2011 ∆%

| ∆% 12 Months Jun 2011/Jun 2010 NSA | ∆% Annual Equivalent Jan-Jun 2011 SA | |

| CPI All Items | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| Food | 3.7 | 5.9 |

| Food at Home | 4.7 | 7.9 |

| Food Away from Home | 2.3 | 3.0 |

| Energy | 20.1 | 11.7 |

| Gasoline | 35.6 | 16.6 |

| Fuel Oil | 37.3 | 44.4 |

| New Vehicles | 4.0 | 8.3 |

| Used Cars and Trucks | 5.1 | 9.4 |

| Medical Care Commodities | 2.9 | 4.3 |

| Services Less Energy Services | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Apparel | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| Shelter | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| Transportation Services | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Medical Care Services | 2.9 | 3.2 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

An important feature of the Jun CPI of the US is the decline in energy, gasoline and fuel prices shown in Table 19. Gasoline prices, with heavy impact on budgets of the middle class, fell 6.8 percent in Jun relative to May after falling 2.0 percent in May relative to Apr; energy declined 4.4 percent in Jun after falling 1.0 percent in May; and fuel oil fell 2.2 percent in Jun after falling 0.8 percent in May. Normalization of refineries and lower prices of oil explain the decline in fuels and energy prices. The overall CPI fell 0.2 percent in Jun compared with increases of 0.2 percent in May, 0.4 percent in Apr and 0.5 percent in Mar. The CPI excluding food and energy rose 0.3 percent in both Jun and May and 0.2 percent for a quarterly annual equivalent rate of 3.2 percent, which is higher than 1.6 percent for headline CPI inflation. The annual equivalent rates of increase of various CPI components in the quarter Mar to Jun 2011 are still quite high.

Table 19, Monthly Percentage Change of Consumer Price Index SA and Annual Equivalent Apr-Jun 2011

| Jun | May | Apr | Mar-May AE | |

| CPI All Items | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| CPI ex Food and Energy | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 3.2 |

| Food | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 4.1 |

| Food at Home | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4.9 |

| Food Away from Home | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 3.2 |

| Energy | -4.4 | -1.0 | 2.2 | -12.5 |

| Gasoline | -6.8 | -2.0 | 3.3 | -20.8 |

| Fuel Oil | -2.2 | -0.8 | 3.2 | 0.5 |

| New Vehicles | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 10.0 |

| Used Cars and Trucks | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 16.8 |

| Medical Care Commodities | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| Services Less Energy Services | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 |

| Apparel | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 11.8 |

| Shelter | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Transport-ation Services | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Medical Care Services | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.7 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

The relative importance or weights of items in the CPI are shown in Table 20. Food and transportation account for 32.1 percent of consumer expenditures and housing for 41.460 percent such that food, transportation and housing account for 73.56 percent of consumer expenditures. Housing is still in recession conditions and a significant part, 24.9 percent, consists of “owners’ equivalent rent,” which is a calculation of what owners would pay if they would rent their own house. The major categories are shown in relief. Motor fuel has risen sharply with gasoline increasing 35.6 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun but accounts for only 5.079 percent of CPI expenditures. Lower income families experience more stress from increases in food and fuel, which represent a higher proportion of their expenses.

Table 20, Relative Importance, 2007-2008 Weights, of Components in the Consumer Price Index, US City Average, Dec 2010

| All Items | 100.000 |

| Food and Beverages | 14.792 |

| Food | 13.742 |

| Food at home | 7.816 |

| Food away from home | 5.926 |

| Housing | 41.460 |

| Shelter | 31.955 |

| Rent of primary residence | 5.925 |

| Owners’ equivalent rent | 24.905 |

| Apparel | 3.601 |

| Transportation | 17.308 |

| Private Transportation | 16.082 |

| New vehicles | 3.513 |

| Used cars and trucks | 2.055 |

| Motor fuel | 5.079 |

| Gasoline | 4.865 |

| Medical Care | 6.627 |

| Medical care commodities | 1.633 |

| Medical care services | 4.994 |

| Recreation | 6.293 |

| Education and Communication | 6.421 |

| Other Goods and Services | 3.497 |

Source: ftp://ftp.bls.gov/pub/special.requests/cpi/cpiri2010.txt

The 12-month rates of increase of PCE price indexes are shown in Table 21. These data are released at the end of the month while the CPI and PPI are released in mid month. Headline 12-month PCE inflation (PCE) has accelerated from slightly over 1 percent in the latter part of 2010 to 2.2 percent in Apr and 2.5 percent in May. Monetary policy uses PCE inflation excluding food and energy (PCEX) on the basis of research showing that current PCEX is a better indicator of headline PCE a year ahead than current headline PCE inflation. The explanation is that commodity price shocks are “mean reverting,” returning to their long-term means after spiking during shortages caused by climatic factors, geopolitical events and the like. Inflation of PCE goods (PCEG) has accelerated sharply reaching 4.6 percent in May, in spite of 12-month declining inflation of PCE durable goods (PCEG-D) while PCE services inflation (PCES) has remained around 1.3 to 1.5 percent. The last two columns of Table 21 show PCE food inflation (PCEF) and PCE energy inflation (PCEE) that have been rising sharply, especially for energy. Monetary policy expects these increases to revert with its indicator PCEX returning to levels that are acceptable for continuing monetary accommodation.

Table 21, Percentage Change in 12 Months of Prices of Personal Consumption Expenditures ∆%

| PCE | PCEG | PCEG -D | PCES | PCEX | PCEF | PCEE | |

| 2011 | |||||||

| May | 2.5 | 4.6 | -0.7 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 22.1 |

| Apr | 2.2 | 4.0 | -1.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 19.6 |

| Mar | 1.9 | 3.0 | -1.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 15.3 |

| Feb | 1.6 | 2.1 | -1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 11.1 |

| Jan | 1.2 | 1.2 | -1.9 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 6.7 |

| 2010 | |||||||

| Dec | 1.1 | 1.0 | -2.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 7.4 |

| Nov | 1.0 | 0.6 | -2.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 4.0 |

| Oct | 1.2 | 0.8 | -1.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 6.3 |

| Sep | 1.3 | 0.5 | -1.4 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 4.2 |

| Aug | 1.4 | 0.6 | -1.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 4.0 |

Notes: percentage changes in price index relative to the same month a year earlier of PCE: personal consumption expenditures; PCEG: PCE goods; PCEG-D: PCE durable goods; PCEX: PCE excluding food and energy; PCEF: PCE food; PCEE: PCE energy goods and services

Source: http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0511.pdf

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0311.pdf

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0411.pdf

The role of devil’s advocate is played by data in Table 22. Headline PCE inflation (PCE) has jumped to 1.6 percent cumulative in the first four months of 2011, which is equivalent to 3.9 percent annual, with PCEG jumping to 3.0 percent cumulative and 7.4 percent annual equivalent, PCEG-D rising 0.8 percent cumulative or 1.9 percent annual, and PCES rising to 0.9 percent cumulative and 2.2 percent annual. PCEX, used in monetary policy, rose to 1.1 percent cumulative or 2.7 percent annual. PCEF has increased by 3.0 percent cumulative, which is equivalent in a full year to 7.4 percent. PCEE has risen to 10.9 percent cumulative or 28.3 percent annual equivalent with decline by 1.2 percent in May.

Table 22, Monthly and Jan-May PCE Inflation and Annual Equivalent Jan-May 2011 and Sep-Dec 2010 ∆%

| PCE | PCEG | PCEG -D | PCES | PCEX | PCEF | PCEE | |

| 2011 | |||||||

| Jan-May 2011 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 10.9 |

| Jan-May 2011 AE | 3.9 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 7.4 | 28.3 |

| May | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | -1.2 |

| Apr | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| Mar | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 3.7 |

| Feb | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 3.5 |

| Jan | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.3 |

| Sep-Dec 2010 | 0.7 | 1.1 | -0.9 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 7.9 |

| Sep-Dec 2010 AE | 2.1 | 3.3 | -2.7 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 25.5 |

| Dec | 0.3 | 0.6 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 4.1 |

| Nov | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Oct | 0.2 | 0.4 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.7 |

| Sep | 0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

Notes:AE: annual equivalent; percentage changes in a month relative to the same month for the same symbols as in Table.

Source: http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0511.pdf

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0311.pdf

http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2011/pdf/pi0411.pdf

An important characteristic of producer price index (PPI) inflation in Table 23 is relatively high monthly rates for the PPI excluding food and energy. Annual equivalent PPI inflation in Jan-Jun 2011 was 8.3 percent while the annual equivalent rate excluding food and energy settled at 3.7 percent. The 12-month rate of increase of the PPI was 3.8 percent in Dec 2010, jumping to 7.0 percent in the 12 months ending in Jun 2011 (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ppi.pdf). The PPI fell 0.4 percent in Jun after increasing only 0.2 percent in May. Instead of mean reversion, the behavior of producer prices has been steady increase on a trend with oscillations caused by episodes of risk aversion in financial markets that reduce positioning of commodity derivatives and other risk financial assets in the carry trade from zero interest rates. Monetary policy creates its own inflation through the carry trade that stimulates commodity futures prices.

Table 23, Producer Price Index ∆%

| Total | Excluding Food and Energy | |

| SA | ||

| Jun | -0.4 | 0.3 |

| May | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Apr | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Mar | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Feb | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Jan | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Dec 2010 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Annual Equivalent Jan-Jun | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| NSA 12 Months Jun | 7.0 | 2.4 |

| NSA 12 Months May | 7.3 | 2.1 |

| NSA 12 Months Apr | 6.8 | 2.1 |

Source: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ppi.nr0.htm

Current price increases from May into June and then into Jul and the expectation for the next six months fell significantly in the Empire State Manufacturing Survey of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shown in Table 24. Indexes for prices paid or inputs and prices received or sales, current or expected in six months, and percentages of responses of higher prices are significantly lower in Jul compared with May. The indexes are still relatively high but the rhythm of price increases is moderating. The expectation for six months of prices received shows rebound of inflationary expectations in percentage responses of higher prices and in the index.

Table 24, FRBNY Empire State Manufacturing Survey, Prices Paid and Prices Received, SA

| Higher | Same | Lower | Index | |

| Current | ||||

| Prices Paid | ||||

| May | 69.89 | 30.11 | 0.00 | 69.89 |

| Jun | 58.16 | 39.80 | 2.04 | 56.12 |

| Jul | 47.78 | 47.78 | 4.44 | 43.33 |

| Prices Received | ||||

| May | 33.33 | 61.29 | 5.38 | 27.96 |

| Jun | 17.35 | 76.53 | 6.12 | 11.22 |

| Jul | 14.44 | 76.67 | 8.89 | 5.56 |

| Six Months | ||||

| Prices Paid | ||||

| May | 70.97 | 26.88 | 2.15 | 68.82 |

| Jun | 58.16 | 38.78 | 3.06 | 55.10 |

| Jul | 56.67 | 37.78 | 5.56 | 51.11 |

| Prices Received | ||||

| May | 40.86 | 53.76 | 5.38 | 35.48 |

| Jun | 30.61 | 58.16 | 11.22 | 19.39 |

| Jul | 38.89 | 52.22 | 8.89 | 30.00 |

Source: http://www.newyorkfed.org/survey/empire/july2011.pdf

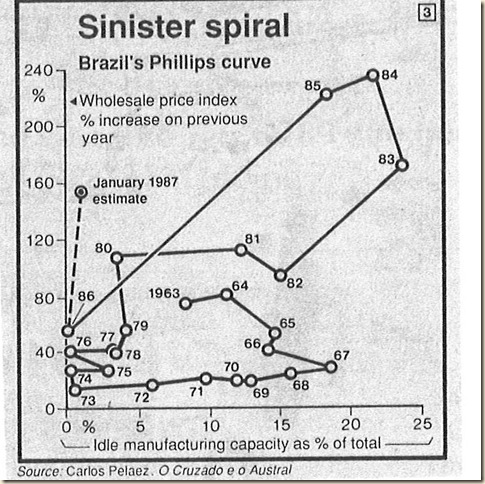

Inflation and unemployment in the period 1966 to 1985 is analyzed by Cochrane (2011Jan, 23) by means of a Phillips circuit joining points of inflation and unemployment. Chart 1 for Brazil in Pelaez (1986, 94-5) was reprinted in The Economist in the issue of Jan 17-23, 1987 as updated by the author. Cochrane (2011Jan, 23) argues that the Phillips circuit shows the weakness in Phillips curve correlation. The explanation is by a shift in aggregate supply, rise in inflation expectations or loss of anchoring. The case of Brazil in Chart 1 cannot be explained without taking into account the increase in the fed funds rate that reached 22.36 percent on Jul 22, 1981 (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm) in the Volcker Fed that precipitated the stress on a foreign debt bloated by financing balance of payments deficits with bank loans in the 1970s; the loans were used in projects, many of state-owned enterprises with low present value in long gestation. The combination of the insolvency of the country because of debt higher than its ability of repayment and the huge government deficit with declining revenue as the economy contracted caused adverse expectations on inflation and the economy. The reading of the Phillips circuits of the 1970s by Cochrane (2011Jan, 25) is doubtful about the output gap and inflation expectations:

“So, inflation is caused by ‘tightness’ and deflation by ‘slack’ in the economy. This is not just a cause and forecasting variable, it is the cause, because given ‘slack’ we apparently do not have to worry about inflation from other sources, notwithstanding the weak correlation of [Phillips circuits]. These statements [by the Fed] do mention ‘stable inflation expectations. How does the Fed know expectations are ‘stable’ and would not come unglued once people look at deficit numbers? As I read Fed statements, almost all confidence in ‘stable’ or ‘anchored’ expectations comes from the fact that we have experienced a long period of low inflation (adaptive expectations). All these analyses ignore the stagflation experience in the 1970s, in which inflation was high even with ‘slack’ markets and little ‘demand, and ‘expectations’ moved quickly. They ignore the experience of hyperinflations and currency collapses, which happen in economies well below potential.”

Chart 1, Brazil, Phillips Circuit 1963-1987

©Carlos Manuel Pelaez, O cruzado e o austral. São Paulo: Editora Atlas, 1986, pages 94-5. Reprinted in: Brazil. Tomorrow’s Italy, The Economist, 17-23 January 1987, page 25.